Abstract

Purpose

Onychomycosis is a nail disorder that is increasing in prevalence worldwide. The psychological and social limitations caused by onychomycosis can potentially undermine the work and social lives of those experiencing these negative effects. This review aimed to evaluate the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) available in the current literature on the impact onychomycosis has on quality of life (QoL).

Methods

A systematic review was performed using the databases PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, ClinicalTrials.gov, and Cochrane Library on July 18, 2017. Only RCTs with clinical effects described in English were included for review.

Results

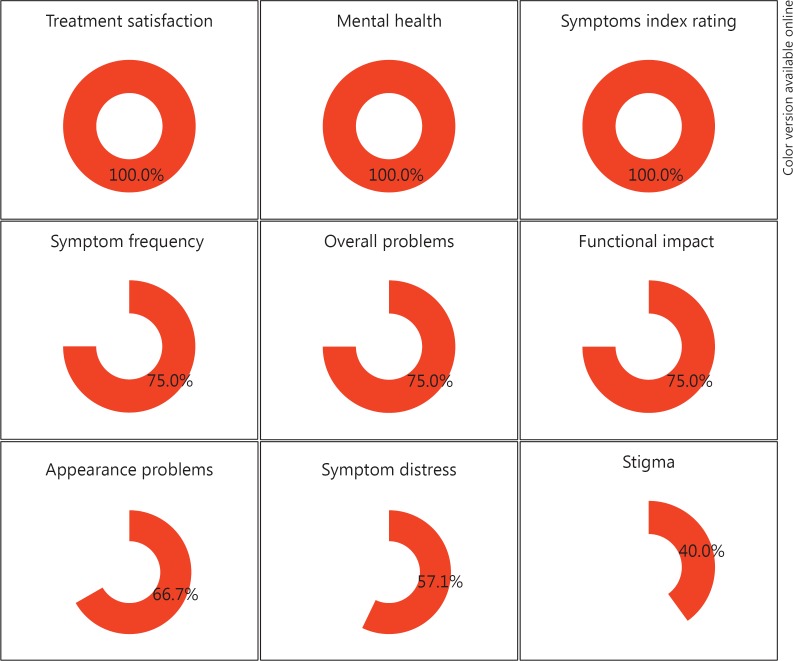

Ten RCTs reported QoL outcomes for patients suffering from onychomycosis. Treatment satisfaction was statistically significant from baseline to end of treatment in 100.0% (4/4) measures which reported on satisfaction with treatment; mental health was also significant in 100.0% (3/3), symptoms index rating in 100.0% (2/2), symptom frequency in 75.0% (3/4), overall problems in 75.0% (3/4), functional activities in 75.0% (6/8), appearance problems in 66.7% (2/3), symptom distress in 57.1% (4/7), and stigma in 40.0% (2/5). The OnyCOE-tTM and the NailQoL were the most used common outcome measures to describe QoL.

Conclusion

The study sanctions that onychomycosis physically and psychologically distresses patients' lives. Further research should include validated outcome measures to more effectively treat onychomycosis.

Keywords: Quality of life, Onychomycosis

Introduction

Finger- and toenails not only serve as protection for the surrounding soft tissue having sensory and mechanical functions, they also function as a visual advertisement of a person's overall health. Onychomycosis, or tinea unguium, is a fungal infection of the nail caused by dermatophytes, yeast, and mold. It is the most common nail disorder experienced worldwide; roughly 50–60% of all nail dystrophies are onychomycosis [1]. It more frequently affects the toenails than the fingernails and is characterized by nail thickening, splitting, roughening, and discoloration. The prevalence of the disease increases with a variety of risk factors such as older age, abnormal nail morphology, immunodeficiency, and genetic factors [2, 3, 4, 5]. Due to its high prevalence, onychomycosis constitutes a substantial health issue as it can have certain negative health consequences such as pain, discomfort, and physical impairment. Moreover, the psychological and social limitations caused by onychomycosis can potentially undermine work and social lives. Reviews on this matter reveal a psychological and psychosocial impact as high as 92% [6]. Some studies have found that onychomycosis has an impact on quality of life (QoL) comparable to that of nonmelanoma skin cancer and benign growths [7]. Still, some physicians choose to not always treat onychomycosis, as they view the condition as a cosmetic concern rather than one of actual medical significance. Most patient concerns stem from the unsightly condition of the nail, thus the impact on patients' QoL can be undervalued and overlooked. This review aimed to evaluate the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) available in the current literature on the impact onychomycosis has on QoL.

Methods

A literature search was done on July 18, 2017 for RCTs reporting QoL in onychomycosis. No date ranges were set. Multiple research databases including Scopus, PubMed, PsycINFO, ClinicalTrials.gov, and Cochrane Library were examined; the search terms were a combination of “onychomycosis” and “quality of life” for all searches. Additional limits included removing duplicates and limiting items to English language and humans. The references of retrieved articles were also searched to identify additional articles that might have been missed in the primary database search. Articles that studied nail, foot, or hand pathology in general and did not separate onychomycosis from other pathologies were excluded from review. Both finger- and toenails were included for this review. When studies reported cure rates, mycological cure was defined as any negative culture or negative PAS, clinical cure was defined as 100% normal nail or clinically normal or clear target nail, and complete cure was defined as both mycological and clinical cure. Papers which met explicit inclusion criteria were included for full-text review.

Results

Study Characteristics

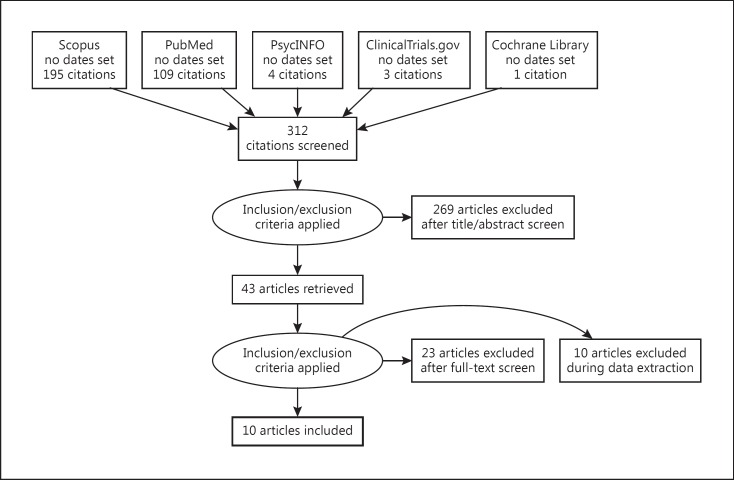

Our literature search of multiple databases yielded 312 studies (Fig. 1). Ten RCTs met our inclusion criteria and were included for review [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] (Table 1). Articles publication dates ranged from June 1998 [12] to February 2017 [14]. The United States was the origin of publication for all articles [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16], with the exception of one article published in Spain [14]. Six RCTs reported QoL data in combination with oral antifungal treatment (4 treated with terbinafine [7, 10, 11], 1 with fluconazole [12], and 1 with various unreported oral antifungal drugs [8]) in 1,998 participants aged 12–87 years. Four RCTs reported topical treatments (two reported ciclopirox [9, 15], one reported efinaconazole [16], and one reported methylaminolevulinate-based photodynamic therapy [14]) in 1,790 participants aged 2–98 years. One RCT reported devices for treatment (1,320-nm Nd:YAG laser [13]) in 10 participants aged > 18 years. Six different QoL outcome measures were used to measure general QoL in participants; a general, investigator-generated QoL questionnaire [12, 15], the Onychomycosis-Related QoL Questionnaire (Onycho-QoL Questionnaire) [14], the NailQoL [7, 13], the OnyCOE-tTM [10, 11, 16], the Bristol Foot Score (BFS) [9], and the Onychomycosis Disease-Specific Questionnaire (ODSQ) [8].

Fig. 1.

Study selection process.

Table 1.

Study characteristics of therapies for the treatment of onychomycosis

| Reference (first author) | Treatment | Age, years (mean ± SD) | Sex (M/F) | Presentation | Culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral antifungals (n = 1,952) | |||||

| Ling [12], 1998 (n = 384) | fluconazole | treatment: | 1,081/487 | DSO (n = 652) | Trichophyton rubrum (n = 375), |

| Turner [8], 2000 (n = 268) | various | 49.9±14.1; | Trichophyton mentagrophytes (n = 7), | ||

| Potter [11], 2006 (n = 504) | terbinafine | control: | Trichophyton tonsurans (n = 2) | ||

| Potter [10], 2007 (n = 504) | terbinafine | 48.7±12.9 | |||

| Warshaw [7], 2007 (n = 292) | terbinafine | ||||

| Topical antifungals (n = 1,790) | |||||

| Friedlander [15], 2013 (n = 40) Malay [9], 2009 (n = 55) Tosti [16], 2014 (n = 1,655) Gilaberte [14], 2017 (n = 40) |

ciclopirox ciclopirox efinaconazole MAL |

treatment: 33.1±9.7; control: 34.9±9.9 |

69/47 | DSO (n = 335), WSO (n = 13), TDO (n = 11), SHO (n = 9), endonyx (n = 8), PSO (n = 5) |

Aspergillus spp. (n = 32), Aspergillus sydowii (n = 2), Aspergillus terreus (n = 2), Candida spp. (n = 71), Candida albicans (n = 10), Epidermophyton floccosum (n = 6), Fusarium spp. (n = 3), Scopulariopsis brevicaulis (n = 2), Trichophyton mentagrophytes (n = 25), Trichophyton rubrum (n = 96) |

| Devices (n = 10) | |||||

| Ortiz et al. [13], 2014 (n = 10) | Nd:YAG laser | >18 | - | - | - |

DSO, distal subungual onychomycosis; MAL, methylaminolevulinate; PSO, proximal subungual onychomycosis; SD, standard deviation; SHO, subungual hyperkeratosis onychomycosis; TDO, total dystrophic onychomycosis; WSO, white superficial onychomycosis.

OnyCOE-tTM

Three studies used the OnyCOE-tTM as their main QoL outcome measure after treatment with antifungals (efinaconazole and terbinafine) [10, 11, 16]. Clinical cure was reported as a combined rate of 88.5% (400/452) [11]. Tosti and Elewski [16] found that the treatment group provided statistically significant improvement in all aspects of the OnyCOE-tTM compared to the vehicle treatment. Potter et al. [11] showed significance in two-sample t tests between the treatment and the placebo group on all items (p < 0.0001 to p = 0.0176) except for the symptom bothersomeness (p = 0.3384). Later, Potter et al. [10] found that only symptom frequency and treatment satisfaction significantly improved in the treatment group compared to the placebo group (p = 0.0395 and p = 0.0077, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Efficacy and clinical outcomes of therapies for the treatment of onychomycosis

| Reference (first author) | Treatment vs. control | Measured, weeks | Clinical results |

QoL results post treatment |

Adverse events | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mycological curea | complete curea | clinical curea | symptom frequency | symptom bothersomeness | physical activities problems | appearance problems | overall problems | stigma | treatment satisfaction | ||||

| OnyCOE-t™ (n = 2,663) | |||||||||||||

| Potter [11], 2006 (n = 504) | terbinafine 250 mg/d for 12 weeks, clinically improved (n = 400) vs. clinically not improved (n = 52) | 11.0 | - | - | 88.5% (400/452) |

p < 0.001 to p = 0.0176b |

p = 0.3384 |

p < 0.001 to p = 0.0176b |

p < 0.001 to p = 0.0176b |

p < 0.001 to p = 0.0176b |

p < 0.001 to p = 0.0176b |

p < 0.001 to p = 0.0176b |

- |

| Potter [10], 2007 (n = 504) | terbinafine 250 mg/d for 12 weeks plus debridement of target toenail (n = 246) vs. terbinafine only (n = 258) | 5.5 | - | - | - | p = 0.0395 | p = 0.3783 | p = 0.1543 | p = 0.9761 | p = 0.9897 | p = 0.4040 | p = 0.0077b | - |

| Tosti [16], 2014 (n = 1,655) |

efinaconazole 10% once daily for 48 weeks (n = 1,236) vs. control (n = 415) | 12.0 | - | - | - | p < 0.001b | p < 0.001b | p = 0.002b | p < 0.001b | p < 0.001b | p = 0.002b | p < 0.001b | - |

| NailQoL (n = 412) | |||||||||||||

| Ortiz [13], 2014 (n = 10) |

1,320-nm Nd:YAG laser, 4 treatments over 24 weeks vs. cryogen spray sham, 4 treatments over 24 weeks |

3.0 | T: 50.0% C: 70.0% |

- | - | Patients felt less self-conscious and embarrassed about the treated toe, no significant difference from control toenail | - | ||||||

| Warshaw [7], 2007 (n = 402) |

terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 m (continuous) vs. terbinafine 500 mg/d for 1 week per m for 3 m (pulse) | 18.0 | T: 71.0% C: 59.0% |

T: 40.0% C: 28.0% |

T: 45.0% C: 29.0% |

NailQoL components Emotion Symptom Function Total |

Mycological cure p = 0.42 p = 0.18 p = 0.69 p = 0.25 |

Complete cure p < 0.01b p = 0.01b p = 0.05b p < 0.01b |

Mild to moderate events: gastrointestinal (n = 14), erythema multiforme (n = 1), rash (n = 1), dizziness and headache (n = 1); all discontinued | ||||

| Investigator-generated QoL questionnaire (n = 421) | |||||||||||||

| Friedlander [15], 2013 (n = 37)c | ciclopirox lacquer vs. vehicle lacquer | 32.0 | T: 77.1% (27/35) C: 100.0% (2/2) |

T: 71.4% (25/35) C: 100.0% (2/2) |

- |

“Would you undergo this treatment again?” Approx. 62% answered “definitely yes,” approx. 32% answered “probably yes,” approx. 2% answered “probably no,” approx. 2% answered “probably no” |

Mild event: reversible, faint yellow-brownish discoloration of the nail plate (n = 1) | ||||||

| Ling [12], 1998 (n = 384) | 4-m daily treatment and 5-m placebo group vs. 6-m daily treatment and 3-m placebo group vs. 9-m treatment group vs. 9-m placebo group | 6.0 | T1: 34.0% (24/70) T2: 49.0% (40/82) T3: 61.0% (46/76) C: 8.0% (6/80) |

T1: 13.0% (9/70) T2: 20.0% (16/82) T3: 26.0% (20/76) C: 1.0% (1/80) |

T1: 14.0% (10/70) T2: 23.0% (19/82) T3: 37.0% (28/76) C: 1.0% (1/81) |

Treatment groups toenail symptoms index scores (p < 0.001)b vs. placebo At the 6-m follow-up visit, the 9-m treatment group had a significantly higher symptoms index rating than the 4-m group (p < 0.05)b At every assessment after baseline, all treatment groups reported significantly greater satisfaction with treatment (p < 0.005)b |

Mild to moderate events: 4-m group (n = 96), 6-m group (n = 94), 9-m group (n = 98), control group (n = 98); discontinued: asymptomatic chemical hepatitis, rash, anxiety, oral ulcers, pleurisy, and recurrence of impotence (n = 1), elevated liver function tests (n = 2) | ||||||

| BFS (n = 55) | |||||||||||||

| Malay [9], 2009 (n = 55, 289 toenails) |

D+TANL vs. DO | 3.0 | T: 76.7% (99/129) C: 0.0% (0/160) |

- | - | DO vs. D+TANL: p = 0.0002b | - | ||||||

| Onychomycosis-Related QoL Questionnaire (n = 40) | |||||||||||||

| Gilaberte [14], 2017 (n = 40) | 3 weekly MAL-PDT sessions vs. 3 weekly placebo PDT sessions | 8.3 | T: 31.8% (7/22) C: 11.1% (2/18) |

T: 18.2% (4/22) C: 5.6% (1/18) |

- | PDT vs. MAL-PDT: p = 0.604 | Mild to moderate events: pain, pigmentation, inflammation, tinea pedis (n = 1); discontinued | ||||||

| ODSQ (n = 259) | |||||||||||||

| Turner [8], 2000 (n = 259) |

4-m daily treatment and 5-m placebo group vs. 6-m treatment and 3-m placebo group vs. 9-m treatment group vs. 9-m placebo group | 9.0 | 38.8% (100/258)*** |

- | 11.6% (30/259)*** |

ODSQ (clinical response) Symptom distress: pain p = 0.107, appearance p < 0.001b Functional impact: activities p = 0.127, appearance p < 0.001b, care p = 0.007b Social stigma: acceptance p = 0.222, desirability p = 0.236, overall problems p = 0.034b |

- | ||||||

|

ODSQ chance scores using MOS-SF36 Mental health: p < 0.01b toe symptoms-pain, foot-related activities, social acceptance, overall protocol; p < 0.001b toe symptoms-appearance, nail appearance Health distress: p < 0.01b toe symptoms-appearance, nail appearance, overall problems; p < 0.001b foot care Physical functioning: p < 0.001b foot care |

|||||||||||||

BFS, Bristol Foot Score; C, control; d, day; D+TANL, debridement and topical ciclopirox 8% daily; DO, debridement only daily; m, month(s); MAL-PDT, methylaminolevulinate-based photodynamic therapy; MOS-SF36, 36-item Medical Outcome Survey-Short Form; ODSQ, Onychomycosis Disease-Specific Questionnaire; PDT, photodynamic therapy; QoL, quality of life; T, treatment.

Mycological cure: negative cultures or negative PAS; clinical cure: 100% normal nail or clinically normal or clear target nail; complete cure: both mycological and clinical cure.

Statistically significant.

Children.

MANOVA.

NailQoL

Two studies reported the NailQoL as their main outcome measure; one used Nd:YAG laser [13] as treatment and the other used terbinafine [7]. Average mycological cure was 60.5% for the treatment group and 64.5% for the control group [7, 13]. Clinical cure was 45.0% for the treatment group and 29.0% for the control [7]. Complete cure was 40.0% for the treatment group and 28.0% for the control group [7]. Warshaw et al. [7] found that NailQoL scores from baseline to 18 months decreased on average by at least 13 points in the patients with complete cure of the target toenail versus those without, and by at least 16 points in the patients with complete cure of all ten toenails versus those without (p < 0.01 and p < 0.01). These observed reductions are statistically significant, and for both outcomes are roughly twice the reduction reported by patients who did not achieve cure status. NailQoL component and total scores of patients achieving mycological cure of the target toenail were not statistically significantly different for patients who did not achieve mycological cure of the target toenail. Similarly, the average change in NailQoL scores for patients with versus without mycological cure of the target toenail alone was not significantly different for any of the component scores or the total NailQoL score. Ortiz et al. [13] found that patients felt less self-conscious and embarrassed about the treated toe versus the untreated toe; however, no significant difference was found for the placebo toe (Table 2).

QoL Questionnaire

Two studies used general QoL questionnaires after treatment with fluconazole [12] or ciclopirox [15]. The weighted average of mycological cure was 52.1% (137/263) for the treatment group and 9.8% (8/82) for the control group [12, 15]. Clinical cure was 25.0% (57/228) for the treatment group and 1.2% (1/81) for the control group [12, 15]. Complete cure was found in 26.6% (70/263) for the treatment group and 3.7% (3/82) for the control group [12, 17]. Friedlander et al. [15] asked participants after treatment with ciclopirox whether they would undergo this treatment again, with > 90% of participants answering yes, indicating an increased QoL effect post treatment. Ling et al. [12] used a questionnaire that addressed general health domains such as mental health and physical functioning as well as disease-specific domains. They found that the treatment groups had significantly better toenail symptoms index scores (p < 0.001) compared to the placebo group; furthermore, at the 6 month follow-up visit, the 9-month fluconazole treatment group also had a significantly higher rating than the 4-month treatment group (p < 0.05). At every assessment after baseline, all fluconazole treatment groups reported significantly greater satisfaction with treatment (p < 0.005), once again indicating an increased QoL effect post treatment.

Various Treatments

Three studies used other various QoL outcome measures: the BFS [9], the ODSQ with the 36-item Medical Outcome Survey-Short Form [8], and the Onycho-QoL Questionnaire [14]. Mycological cure for the BFS was reported per nail sample in 76.7% (99/129 nails) for the treatment group and in 0.0% (0/160 nails) for the control group [9], the Onycho-QoL Questionnaire reported 31.8% for the treatment group and 11.1% for the control group [14], and the ODSQ reported 38.8% combined mycological cure [8]. Clinical cure was reported as a combined cure rate in 11.6% (30/259) [8], and complete cure was 18.2% (4/22) for the treatment group and 5.6% (1/18) for the control group [14]. Turner and Testa [8] reported the ODSQ; the responsiveness change in clinical response showed that patients had an improved QoL effect in the symptom distress group; appearance (p < 0.001), functional impact appearance and care (p < 0.001 and p = 0.007, respectively), and overall problems (p = 0.034) post treatment. Gilaberte et al. [14] reported the Onycho-QoL Questionnaire, which showed a p value of 0.604 for the difference between the treatment and the placebo group.

Combined QoL Outcomes and Adverse Events

Treatment satisfaction was reported as statistically significant from the first measurement at baseline and when it was measured again at the end of treatment in 100.0% (4/4) of the measures which used it, mental health was significant in 100.0% (3/3), symptoms index rating in 100.0% (2/2), symptom frequency in 75.0% (3/4), overall problems in 75.0% (3/4), functional activities in 75.0% (6/8), appearance problems in 66.7% (2/3), symptom distress in 57.1% (4/7), and stigma in 40.0% (2/5) (Fig. 2). Four studies reported adverse events from terbinafine, ciclopirox, methylaminolevulinate-based photodynamic therapy, and various oral treatments [7, 12, 14, 15]. A total of 406 participants experienced mild to moderate adverse events thought to be related to treatment with a frequency of 10.5% (406/3,850); 0.6% (22/3,850) of participants discontinued use of the drug due to these effects. Reasons for discontinued use of treatment included gastrointestinal issues, erythema, rash, dizziness, headache, asymptomatic chemical hepatitis, anxiety, oral ulcers, pleurisy, impotence, elevated liver function tests, pain, pigmentation, inflammation, and tinea pedis.

Fig. 2.

Frequency of combined statistically significant quality of life outcomes.

Discussion

QoL refers to outcome measures, management, and an individual's functional level and acuities of well-being that have been affected by a specific disorder. Research done on QoL applies directly to the clinical setting as it offers insight into disease-specific measures that are responsive to therapeutic change. Physical function and positive mental health are influenced by variables that describe physical symptoms, role fulfillment, as well as psychological and social parameters [18]. In this review, we found ten RCTs that reported QoL outcomes among patients suffering from onychomycosis [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. The OnyCOE-tTM was the most commonly reported measure, with the NailQoL and Drake's QoL Questionnaire as the next frequently reported measures. Mental health, treatment satisfaction, and symptom index were the most consistently statistically significant reported outcomes; however, all extractable measures showed significant improvement. Social stigma of onychomycosis was the only measure with less improvement over time, with 40% of reported outcomes showing significance. Our results demonstrate that most measurable QoL outcome measures reported a statistically significant difference in the treatment satisfaction scores between those patients who showed clinical improvement and those who did not. Thus, onychomycosis has the potential to create serious problems that may significantly affect QoL and well-being [19, 20]. These reported symptoms of onychomycosis have the impendence to be seriously distressing and can lead to an impact on functionality and mental health.

Most activities of daily living encompass some form of manual dexterity or walking and standing. These activities, as well as work and social activities, may be compromised with a positive diagnosis of onychomycosis. Even simple measures such as wearing shoes and appropriately manicuring nails may prove challenging [21]. Fortunately, onychomycosis was not reported as having a significant negative effect on sex life; however, duration of disease as well as fingernails and number of nails involved have been seen to be significant predictors of QoL scores [7, 18, 22, 23, 24]. Another concern is that the presence of a deteriorating mycotic nails may produce adjacent skin injury, thus creating exposure to other organisms and increasing the risk of infection [25, 26]. Psychosocially, the nail represents an important component of communication [19]. Modern society values cosmetic appearance and Canada alone in 2017 has a nail industry worth CAD 5 billon, which is growing annually by 2.4% and em ploys 68,678 people in 24,868 businesses [27]. Attractive, healthy, well-maintained nails signify physical well-being, youth, and cleanliness; consequently, mycotic infections can create issues of self-confidence.

The physical symptoms of onychomycosis are indeed bothersome; however, the psychological implications are even more harrowing [28, 29]. Multiple studies report the presence of anxiety and depression associated with onychomycosis along with low body image and self-esteem, which in turn deteriorates one's sense of worth [30, 31, 32, 33]. Affected persons may additionally be less willing to participate in social and leisure activities, furthering the already deteriorated mental state [34]. Patients with psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, or other skin diseases frequently report experiencing stigmatization due to the presence of their condition [33, 35, 36]. Fingernail versus toenail onychomycosis has been reported to be responsible for a markedly greater psychological impact [33]. This is most likely due to the fact that fingernails are more visible to other people and toenails can be hidden with shoes or socks. Comparison between women and men revealed that only some aspects of social isolation were experienced to a greater extent by the female than the male patients [33].

In addition to the physical and mental implications of onychomycosis, the economic burden is congruently an important QoL discussion. In 1994, Scher [28] reported that 662,000 Medicare patients made 1.3 million visits to physicians in 1989–1990, costing the United States healthcare system USD 43 million. Workplaces also suffer, as one multicenter telephone survey of patients with onychomycosis found that there was an average of 1.8 onychomycosis-related sick days per 258 participants [37]. For individuals who are experiencing financial hardship, an onychomycosis diagnosis can be worrying. Furthermore, onychomycosis may exacerbate financial stress, thereby influencing their livelihood as well as their ability to maintain employment benefits, including health insurance, and potentially manage other financial obligations.

Individuals suffering from concomitant conditions are at a particularly high risk, and a strong clinical incentive is necessary in order to prevent primary disease-related complications [21]. Special patient populations such as the elderly or children are at further risk of physical deterioration, and functional limitations create unique challenges for daily life [21]. The inability to perform basic self-care acts can be quite significant in, for instance, diabetics, where fungal nail infections are known to contribute to the severity of diabetic foot problems. Diabetes mellitus in the elderly is very concerning, and if allowed to evolve unimpeded, progressive disability, cellulitis, osteomyelitis, and tissue necrosis may transpire with the ramification of major lower limb amputation [38]. Even the psychosocial implications of onychomycosis may be intensified in special populations, as the visible reminder of current negative health status and immune system deterioration often has a profound emotional impact [39].

Five QoL measures have been validated for use in patients with onychomycosis; however, very few are used in high-quality clinical trials. The current validated measures for onychomycosis and QoL are the NailQoL, the OnyCOE-tTM, the ODSQ, the Onycho-QoL Questionnaire, and the International Onychomycosis Questionnaire. The first reference of a validated instrument for measuring QoL in onychomycosis, called the Onychomycosis QoL Questionnaire, was produced by Lubeck et al. [23]; the revised version of this instrument has been validated and is in use today [24]. Turner and Testa [8] are responsible for the ODSQ, which can be used in both toe- and fingernails and derives questions from the Lubeck measure. The OnyCOE-tTM is also derived from the Lubeck instrument [11]. The Onycho-QoL Questionnaire is also able to be used in both finger- and toenails and is available in multiple languages [40, 41]. The NailQoL is a combination of the Skindex-29 and 10 additional questions [7].

Clearly, other nail disorders such as trauma, alternative infections, structural abnormalities, psoriasis, paronychia, and other inflammatory diseases cause similar frustration to patients. However, the impact of onychomycosis on QoL compared to other nail disorders was statistically significantly higher; specifically, QoL was more affected in patients having multiple nails involved, in women, and in people aged 60–79 years [42]. Yet, there was no statistically significant difference in the QoL impact between patients having only fingernails or only toenails involved, indicating that the option to hide toenails does not necessarily act to decrease psychosocial impairment [42]. In conclusion, onychomycosis can have substantial negative consequences on QoL. Effective antimycotic therapy might not only improve the physical symptoms of onychomycosis, but also the patient's mental health and social functioning as well as QoL. Onychomycosis needs to be seen as an important problem for a patient which significantly reduces their physical and mental well-being. Individuals' mental perception of the appearance of their nails is an important dermatologic construct as body image dissatisfaction can have a profound impact upon their QoL [43]. Disease-specific instruments have been shown to be better at defining major problems in patients with more accuracy [7, 11, 22, 40]. The continued use of health-related QoL measurements in clinical research allows a more accurate description of how nail disorders affect patients and shows the relevance of some neglected aspects such as pain or emotional trauma [44]. Proper and homogenous assessment of QoL offers us the opportunity to address issues in a more patient-centered approach to treatment.

Disclosure Statement

A.K. Gupta is a clinical trials investigator and speaker for Valeant Canada, a clinical trials investigator for Moberg, and a consultant for Sandoz. R.R. Mays is employed by Mediprobe Research Inc., a site where clinical trials are run under the supervision of A.K. Gupta.

References

- 1.Gupta AK, Jain HC, Lynde CW, MacDonald P, Cooper EA, Summerbell RC. Prevalence and epidemiology of onychomycosis in patients visiting physicians' offices: a multicenter Canadian survey of 15,000 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:244–248. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.104794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdullah L, Abbas O. Common nail changes and disorders in older people. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:173–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elewski BE, Tosti A. Risk factors and comorbidities for onychomycosis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:38–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sigurgeirsson B, Steingrímsson O. Risk factors associated with onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:48–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tosti A, Hay R, Arenas-Guzmán R. Patients at risk of onychomycosis - risk factor identification and active prevention. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19((suppl 1)):13–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lateur N. Onychomycosis: beyond cosmetic distress. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2006;5:171–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2006.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warshaw EM, Foster JK, Cham PMH, Grill JP, Chen SC. NailQoL: a quality-of-life instrument for onychomycosis. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:1279–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner RR, Testa MA. Measuring the impact of onychomycosis on patient quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:39–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1008986826756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malay DS, Yi S, Borowsky P, Downey MS, Mlodzienski AJ. Efficacy of debridement alone versus debridement combined with topical antifungal nail lacquer for the treatment of pedal onychomycosis: a randomized, controlled trial. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2009;48:294–308. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potter LP, Mathias SD, Raut M, Kianifard F, Landsman A, Tavakkol A. The impact of aggressive debridement used as an adjunct therapy with terbinafine on perceptions of patients undergoing treatment for toenail onychomycosis. J Dermatol Treat. 2007;18:46–52. doi: 10.1080/09546630600965004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potter LP, Mathias SD, Raut M, Kianifard F, Tavakkol A. The OnyCOE-t questionnaire: responsiveness and clinical meaningfulness of a patient-reported outcomes questionnaire for toenail onychomycosis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ling MR, Swinyer LJ, Jarratt MT, Falo L, Monroe EW, Tharp M, Kalivas J, Weinstein GD, Asarch RG, Drake L, Martin AG, Leyden JJ, Cook J, Pariser DM, Pariser R, Thiers BH, Lebwohl MG, Babel D, Stewart DM, Eaglstein WH, Falanga V, Katz HI, Bergfeld WF, Hanifin JM, Young MR, et al. Once-weekly fluconazole (450 mg) for 4, 6, or 9 months of treatment for distal subungual onychomycosis of the toenail. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:S95–S102. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70492-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortiz AE, Truong S, Serowka K, Kelly KM. A 1,320-nm Nd:YAG laser for improving the appearance of onychomycosis. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1356–1360. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilaberte Y, Robres M, Frias MP, Garcia-Doval I, Rezusta A, Aspiroz C. Methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy for onychomycosis: a multicentre, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:347–354. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedlander SF, Chan YC, Chan YH, Eichenfield LF. Onychomycosis does not always require systemic treatment for cure: a trial using topical therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:316–322. doi: 10.1111/pde.12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tosti A, Elewski BE. Treatment of onychomycosis with efinaconazole 10% topical solution and quality of life. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:25–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedlander SF. A 9-year-old boy with mild distal-lateral subungual onychomycosis. Adv Stud Med. 2005;5:S624–S628. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lubeck DP. Measuring health-related quality of life in onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:S64–S68. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70487-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drake LA. Impact of onychomycosis on quality of life. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1997;87:507–511. doi: 10.7547/87507315-87-11-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zienicke HC, Korting HC, Lukacs A, Braun-Falco O. Dermatophytosis in children and adolescents: epidemiological, clinical, and microbiological aspects changing with age. J Dermatol. 1991;18:438–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1991.tb03113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elewski BE. Onychomycosis. Treatment, quality of life, and economic issues. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:19–26. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200001010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drake LA, Patrick DL, Fleckman P, Andr J, Baran R, Haneke E, Sapède C, Tosti A. The impact of onychomycosis on quality of life: development of an international onychomycosis-specific questionnaire to measure patient quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lubeck DP, Patrick DL, McNulty P, Fifer SK, Birnbaum J. Quality of life of persons with onychomycosis. Qual Life Res. 1993;2:341–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00449429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lubeck DP, Gause D, Schein JR, Prebil LE, Potter LP. A health-related quality of life measure for use in patients with onychomycosis: a validation study. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:121–129. doi: 10.1023/a:1026429012353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rich P. Special patient populations: onychomycosis in the diabetic patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:S10–S12. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Findley K, Oh J, Yang J, Conlan S, Deming C, Meyer JA, Schoenfeld D, Nomicos E, Park M; NIH Intramural Sequencing Center Comparative Sequencing Program, Kong HH, Segre JA. Topographic diversity of fungal and bacterial communities in human skin. Nature. 2013;498:367–370. doi: 10.1038/nature12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hair & Nail Salons - Canada Market Research Report IBISWorld. www.ibisworld.ca/industry/hair-nail-salons.html (accessed August 2, 2017)

- 28.Scher RK. Onychomycosis is more than a cosmetic problem. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130((suppl 43)):15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb06087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta AK, Jain HC, Lynde CW, Watteel GN, Summerbell RC. Prevalence and epidemiology of unsuspected onychomycosis in patients visiting dermatologists' offices in Ontario, Canada - a multicenter survey of 2001 patients. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:783–787. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chacon A, Franca K, Fernandez A, Nouri K. Psychosocial impact of onychomycosis: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1300–1307. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Health-related quality of life in patients with nail disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:313–320. doi: 10.2165/11592120-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shuster S. Depression of self-image by skin disease. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1991;156:53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szepietowski JC, Reich A, National Quality of Life in Dermatology Group. Stigmatisation in onychomycosis patients a population-based study. Mycoses. 2009;52:343–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaw JW, Joish VN, Coons SJ. Onychomycosis: health-related quality of life considerations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;20:23–36. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200220010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Helplessness as Predictor of Perceived Stigmatization in Patients with Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis ResearchGate. www.researchgate.net/publication/244914407_Helplessness_as_Predictor_of_Perceived_Stigmatization_in_Patients_with_Psoriasis_and_Atopic_Dermatitis (accessed August 7, 2017)

- 36.Drake L. Quality of life issues for patients with fungal nail infections. AIDS Patient Care. 1995;9((suppl 1)):S15–S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts DT. Prevalence of dermatophyte onychomycosis in the United Kingdom: results of an omnibus survey. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126((suppl 39)):23–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy L. Epidemiology of onychomycosis in special-risk populations. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1997;87:546–560. doi: 10.7547/87507315-87-12-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gregory N. Special patient populations: onychomycosis in the HIV-positive patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:S13–S16. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szepietowski JC, Reich A, Pacan P, Garlowska E, Baran E, Polish Onychomycosis Study Group Evaluation of quality of life in patients with toenail onychomycosis by Polish version of an international onychomycosis-specific questionnaire. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:491–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milobratović D, Janković S, Vukičević J, Marinković J, Janković J, Railić Z. Quality of life in patients with toenail onychomycosis. Mycoses. 2013;56:543–551. doi: 10.1111/myc.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belyayeva E, Gregoriou S, Chalikias J, Kontochristopoulos G, Koumantaki E, Makris M, Koti I, Katoulis A, Katsambas A, Rigopoulos D. The impact of nail disorders on quality of life. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:366–371. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Johnson AM. Cutaneous body image: empirical validation of a dermatologic construct. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:405–406. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tabolli S, Alessandroni L, Gaido J, Sampogna F, Di Pietro C, Abeni D. Health-related quality of life and nail disorders. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:255–259. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]