Abstract

Background

Consensus is lacking regarding intervention for patients with acute lower limb ischaemia (ALI). The aim was to study amputation‐free survival in patients treated for ALI by either primary open or endovascular revascularization.

Methods

The Swedish Vascular Registry (Swedvasc) was combined with the Population Registry and National Patient Registry to determine follow‐up on mortality and amputation rates. Revascularization techniques were compared by propensity score matching 1 : 1.

Results

Of 9736 patients who underwent open surgery and 6493 who had endovascular treatment between 1994 and 2014, 3365 remained in each group after propensity score matching. Results are from the matched cohort only. Mean age of the patients was 74·7 years; 47·5 per cent were women and mean follow‐up was 4·3 years. At 30‐day follow‐up, the endovascular group had better patency (83·0 versus 78·6 per cent; P < 0·001). Amputation rates were similar at 30 days (7·0 per cent in the endovascular group versus 8·2 per cent in the open group; P = 0·113) and at 1 year (13·8 versus 14·8 per cent; P = 0·320). The mortality rate was lower after endovascular treatment, at 30 days (6·7 versus 11·1 per cent; P < 0·001) and after 1 year (20·2 versus 28·6 per cent; P < 0·001). Accordingly, endovascular treatment had better amputation‐free survival at 30 days (87·5 versus 82·1 per cent; P < 0·001) and 1 year (69·9 versus 61·1 per cent; P < 0·001). The number needed to treat to prevent one death within the first year was 12 with an endovascular compared with an open approach. Five years after surgery, endovascular treatment still had improved survival (HR 0·78, 99 per cent c.i. 0·70 to 0·86) but the difference between the treatment groups occurred mainly in the first year.

Conclusion

Primary endovascular treatment for ALI appeared to reduce mortality compared with open surgery, without any difference in the risk of amputation.

Short abstract

Endovascular may save lives

Introduction

Treatment for acute lower limb ischaemia (ALI) represents a major challenge for vascular specialists, largely because of high amputation and death rates1, 2, 3, 4, 5. The 1‐year amputation‐free survival rate is approximately 50–70 per cent6, 7. The optimal choice of treatment remains undefined despite considerable research effort8. Previous reports9, 10, 11, 12 highlighted that differences in outcome are dependent on the aetiology of the occlusion: either arterial thrombosis, embolus or aneurysm. These aetiologies may represent different diseases, with mutual symptoms, but requiring different treatment for optimal outcome4.

Open surgery was previously the exclusive treatment option. After the advent of catheter‐directed thrombolytic therapy, its use was compared with open surgery in several RCTs in the mid‐1990s8. There was no overall difference in limb salvage or death at 1 year between initial surgery or thrombolysis8. During the past two decades, the treatment of ALI has developed appreciably with the introduction of new advanced and, more frequently, endovascular techniques6. There are no contemporary large‐scale comparisons between open and endovascular interventions for ALI. The lack of consensus on the treatment of ALI has led to wide variation in practice. Half of patients in the USA are treated with open surgery6; in contrast, in Scandinavia patients are more often treated with thrombolysis. The European Society of Vascular Surgery has initiated a process of developing clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of ALI, to be published in late 2019.

This nationwide cohort study aimed to compare short‐ and long‐term results after open or endovascular intervention for ALI, with amputation‐free survival as the primary endpoint.

Methods

The study was approved by the regional ethical review board in Uppsala, Sweden (2014/325) and registered with prespecified outcomes at http://clinicaltrials.gov in July 2016 (identifier NCT02835027).

The Swedish Vascular Registry (Swedvasc) started in 1987 and has had nationwide coverage since 1994. More than 95 per cent of vascular surgical procedures performed in Sweden are registered prospectively13, 14, 15.

The Swedvasc database was assessed on 8 June 2015 and all patients registered with ALI between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 2014 were identified. During the target interval, the database has been updated four times, when variables were adjusted, resulting in five separate databases; these were merged. The study population was limited to patients who had an emergency or urgent admission, with symptoms of acute onset and duration less than 14 days (Fig. S1, supporting information). Only ALI due to occlusions below the inguinal ligament were included, to create a more homogeneous study population.

ALI secondary to trauma, dissection, bleeding or graft infection was excluded because the focus was on acute embolic or thrombotic arterial occlusions. Data are collected prospectively in the Swedvasc. The registry has been validated internally (for accuracy of data) and externally (for completeness, comparing with other databases)13, 14, 15.

Patients

Patients with ALI were categorized into either initial open surgical or endovascular revascularization groups, according to the type of procedure used to treat the acute ischaemic event. The most common types of open surgery were thromboembolectomy, bypass surgery and thromboendarterectomy; the most common type of endovascular treatment was thrombolysis, often in combination with percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) and/or stenting, or stenting alone. Patients who had hybrid surgery (open and endovascular performed simultaneously) were assigned to the open group. Thus, patients in the endovascular group exclusively received endovascular surgery. If a patient was treated for ALI, with, for example, thrombolysis, and later was treated electively for the underlying lesion, the second operation was not included in the present analysis, which focused on the primary intervention alone.

Outcomes

In Sweden, every resident has a unique personal identification number (PIN), making it possible to combine registry information, without loss to follow‐up. All deaths in Sweden are registered in the Population Registry16 and lower limb amputations are registered in the National Patient Registry (NPR), which has high validity17. Accurate survival data were obtained by cross‐linking the PIN with the NPR in June 2016. The combination of these databases made it possible to obtain complete follow‐up data on mortality and amputations. Only major amputations were included in the analyses, defined as those above ankle level. Patency at 30 days was reported to the Swedvasc registry by the vascular surgeon after clinical examination, often, but not always, combined with duplex ultrasound imaging.

Definitions

The severity of limb ischaemia at presentation was registered in Swedvasc according to the Rutherford classification scale and the ankle : brachial pressure index18. Prospectively recorded, preoperative co‐morbidities and risk factors were: hypertension (BP over 140/90 mmHg), diabetes mellitus (treated with diet, oral medication or insulin), heart disease (history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, coronary bypass or heart valve surgery), cerebrovascular events (stroke or transient ischaemic attack), renal impairment (serum creatinine 150 mmol/l and above, or dialysis) and pulmonary disease (any diagnosed pulmonary disease).

Statistical analysis

The Swedvasc database has a high completeness of registered procedures, with more than 95 per cent of all vascular surgical procedures registered prospectively; however, full information on co‐morbidities at presentation was missing for some patients (9–12 per cent). Multiple imputation to replace missing values in the database was performed using the R package mice (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), generating 100 imputations. These imputations were analysed one at a time, pooling the results using Rubin's rules19. Missing information on aetiology for arterial occlusion was not completely at random. A manual chart review was performed at Uppsala University Hospital to create a model for imputing these data (Appendix S1, supporting information).

To select suitable co‐variables, current knowledge and directed acyclic graphs were used20. A propensity score was constructed to control for treatment selection bias. The score included aetiology of the occlusion, time interval (1994–2000, 2001–2007, 2008–2014), patient age, level of arterial occlusion, degree of ischaemia (Rutherford classification), heart disease, cerebrovascular event, renal impairment and pulmonary disease in the logistic regression model to predict the probability that the patients would receive endovascular surgery.

Next, patients from both treatment groups were matched 1 : 1 based on an estimated propensity score (the propensity scores could not differ by more than 0·001 to be considered a match). The matches were exact for aetiology of occlusion and time interval (Appendix S1, supporting information).

Survival distributions for matched patients were compared using Kaplan–Meier curves and the log rank test. Time at risk was calculated for each participant from the date of surgery until the date of amputation or death, or the end of the study interval (31 March 2016), whichever occurred first. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) for mortality, amputation and the composite endpoint: death or amputation.

Statistical significance was expressed in terms of both P values and 99 per cent confidence intervals. χ2 test was used for analysis of categorical variables and independent‐samples t test for continuous data. P < 0·010 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS® version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) and R version 3.1.0.

Results

From an initial database of 18 707 patients, 16 229 procedures in 13 308 unique patients were identified using the inclusion criteria (Fig. S1, supporting information). The most common reason for exclusion was suprainguinal arterial occlusion. Some 7276 treatments (44·8 per cent) were undertaken in eight university hospitals, and the remainder in county or district hospitals. The mean follow‐up was 51·6 (99 per cent c.i. 50·5 to 52·7) months.

Before propensity score matching, patients treated with open surgery were older, had more severe ischaemia, more proximal occlusions, and more often had a history of ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and renal or respiratory insufficiency. Men, smoking, hypertension and diabetes were more common in the endovascular surgery group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics before and after propensity score matching

| Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open surgery (n = 9736) | Endovascular treatment (n = 6493) | P * | Open surgery (n = 3365) | Endovascular treatment (n = 3365) | P * | |

| Mean age (years) | 75·7 (75·3, 76·0) | 74·4 (74·1, 74·8) | < 0·001† | 74·5 (74·0, 75·1) | 74·8 (74·3, 75·3) | 0·420† |

| Women (%) | 50·2 (48·9, 51·5) | 46·5 (44·8, 48·0) | < 0·001 | 46·2 (44·0, 48·4) | 48·8 (46·6, 50·1) | 0·071 |

| Time interval | ||||||

| 1994–2000 | 35·3 (34·1, 36·6) | 24·1 (22·7, 25·5) | < 0·001 | 27·0 (25·0, 29·0) | 27·0 (25·0, 29·0) | 1·000 |

| 2001–2007 | 27·3 (26·1, 28·5) | 27·9 (26·4, 29·3) | 0·413 | 28·2 (26·2, 30·2) | 28·2 (26·2, 30·2) | 1·000 |

| 2008–2014 | 37·4 (36·1, 38·7) | 48·0 (46·4, 49·6) | < 0·001 | 44·8 (42·6, 47·0) | 44·8 (42·6, 47·0) | 1·000 |

| Aetiology (%) | ||||||

| Thrombosis | 43·3 (42·0, 44·6) | 69·4 (67·0, 70·9) | < 0·001 | 63·7 (61·6, 65·8) | 63·7 (61·6, 65·8) | 1·000 |

| Embolus | 52·8 (51·5, 54·1) | 28·2 (26·8, 29·6) | < 0·001 | 34·1 (32·0, 36·2) | 34·1 (32·0, 36·2) | 1·000 |

| Popliteal aneurysm | 3·9 (3·4, 4·4) | 2·4 (1·9, 2·9) | < 0·001 | 2·2 (1·5, 2·9) | 2·2 (1·5, 2·9) | 1·000 |

| Rutherford classification (%) | ||||||

| I | 9·3 (8·6, 10·1) | 16·9 (15·7, 18·1) | < 0·001 | 13·7 (12·2, 15·2) | 14·5 (12·9, 16·1) | 0·381 |

| IIa | 26·0 (24·8, 27·1) | 51·6 (50·0, 53·2) | < 0·001 | 42·2 (40·0, 44·4) | 41·9 (39·7, 44·1) | 0·838 |

| IIb | 62·9 (61·7, 64·2) | 31·3 (29·8, 32·8) | < 0·001 | 43·9 (41·8, 46·0) | 43·3 (41·1, 45·5) | 0·671 |

| III | 1·8 (1·4, 2·1) | 0·2 (0·0, 0·3) | < 0·001 | 0·2 (0·1, 0·3) | 0·2 (0·1, 0·2) | 0·830 |

| Level of occlusion (%) | ||||||

| Femoral | 77·1 (76·0, 78·2) | 37·5 (36·0, 39·1) | < 0·001 | 59·9 (57·8, 62·0) | 60·6 (58·4, 62·8) | 0·565 |

| Popliteal | 16·4 (15·5, 17·4) | 50·7 (49·1, 52·3) | < 0·001 | 29·6 (27·6, 31·6) | 29·7 (27·7, 31·7) | 0·945 |

| Below popliteal | 6·4 (5·8, 7·1) | 11·8 (10·7, 12·8) | < 0·001 | 10·5 (9·2, 11·9) | 9·7 (8·3, 11·0) | 0·329 |

| Smoking (%) | ||||||

| Current | 23·2 (22·1, 24·3) | 24·8 (23·5, 26·2) | 0·026 | 24·1 (22·3, 26·0) | 25·2 (23·3, 25·2) | 0·418 |

| Previous | 14·6 (13·7, 15·6) | 18·6 (17·3, 19·8) | < 0·001 | 18·1 (16·3, 19·9) | 17·6 (15·9, 19·3) | 0·706 |

| Never | 62·2 (60·9, 63·5) | 56·6 (54·9, 58·2) | < 0·001 | 57·8 (55·6, 60·0) | 57·2 (55·0, 59·4) | 0·665 |

| Co‐morbidities (%) | ||||||

| Hypertension | 57·8 (56·5, 59·1) | 61·7 (60·2, 63·3) | < 0·001 | 59·9 (57·7, 62·1) | 61·9 (59·7, 64·0) | 0·171 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20·1 (19·1, 21·1) | 23·1 (21·8, 24·5) | < 0·001 | 20·0 (18·2, 21·8) | 23·8 (21·9, 25·7) | 0·002 |

| Heart disease | 64·1 (62·9, 65·4) | 54·2 (52·7, 55·8) | < 0·001 | 57·2 (55·0, 59·4) | 57·2 (55·0, 59·4) | 0·972 |

| Cerebrovascular events | 25·8 (24·7, 26·9) | 17·6 (16·4, 18·9) | < 0·001 | 18·9 (17·1, 20·6) | 19·1 (17·4, 20·8) | 0·867 |

| Renal impairment | 11·3 (10·5, 12·1) | 7·7 (6·9, 8·6) | < 0·001 | 8·3 (7·1, 9·5) | 8·1 (6·9, 9·3) | 0·790 |

| Pulmonary disease | 16·1 (15·1, 17·1) | 13·1 (12·0, 14·2) | < 0·001 | 14·3 (12·7, 15·9) | 14·5 (13·0, 16·1) | 0·798 |

Values in parentheses are 99 per cent confidence intervals.

χ2 test, except

independent‐samples t test.

After propensity score matching, 3365 patients remained in each treatment group, and the results hereafter focus entirely on comparing these patients. Their mean age was 74·7 years (71·7 years for 3533 men, and 78·9 years for 3197 women). The only remaining difference was a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus in the endovascular group (23·8 versus 20·0 per cent; P = 0·002) (Table 1).

Revascularization techniques

In the open surgery group, 61·3 per cent underwent thromboembolectomy, 25·6 per cent surgical bypass and 13·1 per cent thromboendarterectomy. In the endovascular group, 49·9 per cent underwent thrombolysis alone, 31·7 per cent thrombolysis with stent and/or percutaneous PTA, and 18·4 per cent stenting with or without PTA or subintimal angioplasty. In the open surgery group, 7·5 per cent were hybrid operations.

Early complications and patency

Any complication during 30 days after surgery occurred in 31·3 per cent of patients after open and 22·6 per cent after endovascular revascularization (P < 0·001). Bleeding complications occurred in 5·0 per cent after open and 7·1 per cent after endovascular procedures (P = 0·021). Perioperative stroke occurred in 0·2 and 0·4 per cent respectively (P = 0·190). Other complications (such as myocardial infarction and stroke) were also distributed similarly between the groups (Table 2). There was a trend towards more fasciotomies after open surgery (P = 0·014). The overall 30‐day primary patency rate was 78·6 per cent in the open and 83·0 per cent in the endovascular group (P < 0·001).

Table 2.

Outcomes in the matched cohort

| Overall (n = 6730) | Open surgery (n = 3365) | Endovascular treatment (n = 3365) | P * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes at 30 days (%) | ||||

| Primary patency | 80·8 (79·6, 82·0) | 78·6 (76·8, 80·4) | 83·0 (81·4, 84·6) | < 0·001 |

| Fasciotomy | 6·4 (5·6, 7·2) | 7·5 (6·3, 8·7) | 5·4 (4·4, 6·4) | 0·014 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2·9 (2·3, 3·5) | 3·1 (2·4, 3·9) | 2·6 (1·9, 3·3) | 0·342 |

| Stroke | 1·7 (1·3, 2·1) | 1·4 (0·9, 1·9) | 2·1 (1·5, 2·8) | 0·077 |

| Amputation | 7·6 (6·7, 8·4) | 8·2 (7·0, 9·4) | 7·0 (5·9, 8·1) | 0·113 |

| Death | 8·9 (8·0, 9·8) | 11·1 (9·7, 12·5) | 6·7 (5·6, 7·8) | < 0·001 |

| Amputation‐free survival | 84·8 (83·5, 85·8) | 82·1 (80·3, 83·7) | 87·5 (86·0, 88·9) | < 0·001 |

| Outcomes at 1 year (%) | ||||

| Amputation | 14·3 (13·2, 15·4) | 14·8 (13·2, 16·4) | 13·8 (12·3, 15·3) | 0·320 |

| Death | 24·4 (23·1, 25·7) | 28·6 (26·6, 30·6) | 20·2 (18·4, 22·0) | < 0·001 |

| Amputation‐free survival | 65·7 (64·2, 67·2) | 61·6 (59·4, 63·7) | 69·9 (67·9, 71·9) | < 0·001 |

Values in parentheses are 99 per cent confidence intervals.

χ2 test.

Main outcomes

The amputation rate at 30 days was 7·0 per cent after endovascular and 8·2 per cent after open surgery (P = 0·113). Respective 30‐day mortality rates were 6·7 and 11·1 per cent (P < 0·001). The amputation‐free survival rate was 87·5 per cent after endovascular and 82·1 per cent after open treatment (P < 0·001). The same pattern was observed 1 year after surgery: similar amputation rates but superior survival and amputation‐free survival after endovascular surgery (Table 2). The 1‐year risk of death was 28·6 per cent after open surgery and 20·2 per cent in the endovascular group (P < 0·001). This risk difference corresponded to a number needed to treat of 12 patients to prevent one death within the first year, if primary treatment was changed from open to endovascular surgery.

Cox regression analyses revealed the same pattern at 30 days, 1 year and 5 years after surgery (Table 3). At 5 years, the endovascular group had lower mortality rates (HR 0·78, 99 per cent c.i. 0·70 to 0·86) and superior amputation‐free survival (HR 0·82, 0·75 to 0·90).

Table 3.

Hazard ratios for amputation and death after endovascular treatment versus open surgery

| Hazard ratio for endovascular treatment versus open surgery | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Outcomes at 30 days | ||

| Amputation | 0·84 (0·65, 1·10) | 0·098 |

| Death | 0·58 (0·45, 0·74) | < 0·001 |

| Amputation and/or death | 0·67 (0·56, 0·81) | < 0·001 |

| Outcomes at 1 year | ||

| Amputation | 0·92 (0·76, 1·12) | 0·270 |

| Death | 0·66 (0·57, 0·77) | < 0·001 |

| Amputation and/or death | 0·73 (0·65, 0·83) | < 0·001 |

| Outcomes at 5 years | ||

| Amputation | 1·01 (0·85, 1·19) | 0·937 |

| Death | 0·78 (0·70, 0·86) | < 0·001 |

| Amputation and/or death | 0·82 (0·75, 0·90) | < 0·001 |

Values in parentheses are 99 per cent confidence intervals. The analysis included 3365 patients in each group. Hazard ratios were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression.

A landmark analysis was performed starting 1 year after index surgery to interpret the remaining effect of the intervention after events from the first year had been excluded. When time censoring was set at 5 years, there was no statistically significant difference in the risk of adverse events after endovascular treatment compared with open surgery: amputation (HR 1·45, 99 per cent c.i. 0·96 to 2·17), death (HR 0·90, 0·78 to 1·04) and amputation and/or death (HR 0·96, 0·83 to 1·12).

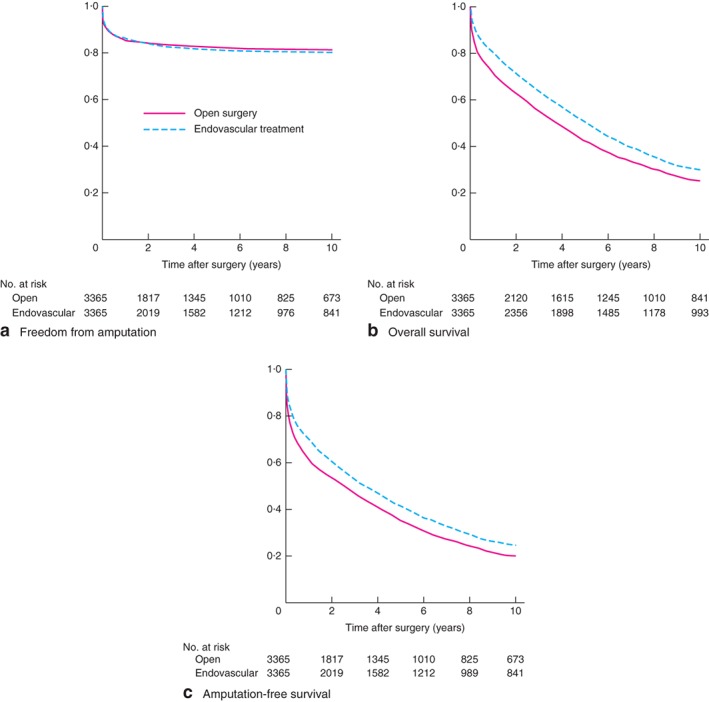

Curves for amputation were similar in the two treatment groups up to 10 years after the intervention (P = 0·322) (Fig. 1 a). There were significant differences between the groups in overall and amputation‐free survival (both P < 0·001) (Fig. 1 b,c). The survival curves showed a difference between the treatment groups during the first year of follow‐up. Thereafter, mortality rates were similar.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves comparing a freedom from amputation, b overall survival and c amputation‐free survival after open or endovascular revascularization. a P = 0·322, b,c P < 0·001 (log rank test)

In a sensitivity analysis, amputation‐free survival after endovascular and open surgery was investigated by type of arterial occlusion (Fig. S2, supporting information). The amputation‐free survival rate was higher after endovascular intervention, irrespective of whether the ALI was caused by embolic or thrombotic occlusion (P < 0·001).

Discussion

ALI is a severe condition threatening both life and limb. The present study demonstrated similar amputation rates, but improved survival after primary endovascular intervention compared with open surgery. The results suggest that one life could be saved during the first year, if the primary treatment were changed from open to endovascular in 12 patients.

In the mid‐1990s, three randomized trials addressed the optimal treatment strategy for patients with ALI. A Cochrane database meta‐analysis of the studies8 concluded that there was no overall difference in limb salvage, death or amputation‐free survival at 30 days or 1 year. A limitation of this meta‐analysis was the low precision of the estimates.

Ouriel and colleagues21 randomized 114 patients with ALI of less than 7 days' duration to thrombolysis with urokinase or open surgery. At 1 year, the cumulative risk of amputation (18 per cent) was equal in the two groups, whereas thrombolysis was associated with a reduction in mortality. The STILE (Surgery versus Thrombolysis for Ischaemia of the Lower Extremity) trial11 randomized 393 patients with non‐embolic lower extremity ischaemia of less than 6 months' duration. A higher percentage of patients randomized to thrombolysis had treatment failure at 30 days, which led to premature termination of the trial. Most patients in the STILE trial, however, had chronic ischaemia. Subsequent subgroup analysis indicated that patients presenting with acute ischaemia (symptoms for less than 14 days) and randomized to thrombolysis had significantly better limb salvage (89 versus 70 per cent) and amputation‐free survival. Finally, the TOPAS (Thrombolysis or Peripheral Arterial Surgery) trial22, 23 randomized 544 patients with acute lower extremity ischaemia secondary to native arterial or bypass graft occlusion of less than 14 days' duration. Survival and amputation‐free survival rates at 12 months were similar, but significantly more bleeding occurred in those randomized to urokinase.

The present study compared first‐line endovascular treatment with open surgery. There was a trend towards more bleeding complications associated with endovascular treatment; however, stroke/intracranial haemorrhage rates were similar in the two groups.

One year after intervention and beyond, the two survival curves were parallel, indicating that the propensity score match was successful in addressing confounding and selection bias. The difference in effects of the two treatments occurred closer to the intervention. The landmark analysis confirmed the lack of difference in risk of late events, although there was a trend towards more late amputations after endovascular intervention. Results from the landmark analysis should be interpreted with caution, however, as the co‐variable balance achieved by the propensity score matching might no longer be accurate.

It was predicted that the advantage of endovascular treatment could be more pronounced in patients with a thrombotic occlusion, but subgroup analysis suggested the opposite (Fig. S2, supporting information). The advantage of the less invasive technique seemed to be in the most vulnerable patients with embolic occlusions.

There are a number of possible reasons why endovascular treatment may offer additional advantages. First, it can be done under local anaesthesia, which is convenient because many patients with ALI are elderly and fragile with multiple co‐morbidities4. Second, endovascular treatment includes accurate angiographic imaging, and possibly a more directed and definitive therapeutic approach24. It also ensures a completion control at the end of the procedure, which is not always the case after open surgery.

Several studies7, 11, 22 have reported that initial thrombolytic therapy can reduce the need for subsequent surgical treatment. If unsuccessful, thrombolysis can be followed promptly by surgery, whereas the reverse order is contraindicated owing to the risk of bleeding4. A noteworthy observation from the STILE trial11 was that patients in whom surgery failed had more than twice the risk of major amputation compared with those who had initial unsuccessful thrombolysis.

For patients with severe ischaemia and a motor deficit (Rutherford class IIb), the previous recommendation25 has been urgent surgery because of the relatively long time required for revascularization with thrombolysis. Emergency lower extremity bypass for ALI, however, is associated with increased rates of serious in‐hospital adverse events, major amputation rates and mortality compared with elective bypass surgery26. There are several possible explanations for these difficulties, including a lack of time for preoperative optimization, longer procedures, greater blood loss and the use of a prosthetic conduit26. In recent years, several endovascular solutions have evolved for more severe ischaemia, with the introduction of aspiration, percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy and rheolytic techniques. Percutaneous mechanical devices enhance the surgeon's ability to remove thrombus quickly, resulting in lower doses of thrombolytic drugs and reducing the time to reperfusion1. Some studies27, 28 have indicated that, when rapid reperfusion is needed, percutaneous local mechanical thrombectomy, with or without thrombolysis, may be used in a safe and efficient way, even in patients with severe ischaemia and a motor deficit. Endovascular treatment may also serve as a valuable first‐line approach, which can be followed later in elective settings by surgical treatment when the patient and circumstances have been optimized29.

A sizeable proportion of the patients treated here using endovascular methods had severe ischaemia with neurological symptoms (Rutherford class IIb). Many of the patients with the most severe ischaemia (Rutherford class IIb and III) were, however, excluded by the propensity score matching because most were treated with open surgery. After propensity score matching, severe ischaemia occurred in approximately 44 per cent in both groups (Table 1). During the study, a shift towards more endovascular and hybrid revascularization techniques was observed (Fig. S3, supporting information).

The major limitation of this study was the observational design. Propensity score matching is a useful tool to account for observed differences between two treatment groups in order to isolate the effect of a treatment; however, propensity scores cannot adjust for unobserved differences between groups. It is possible that unobserved co‐variables might have influenced the choice of treatment as well as the outcome, a phenomenon labelled residual confounding. Furthermore, the distinction between thrombosis and embolus can sometimes be difficult, especially in an ageing population that often has established atherosclerotic disease of the arteries. When a patient presents with both lower limb atherosclerosis and a source of embolus, not only classification but also treatment is complex4.

In this large propensity score‐matched nationwide cohort study, primary endovascular treatment of ALI appears to be beneficial, with significantly better short‐term survival and amputation‐free survival compared with primary open revascularization.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Editor's comments

Supporting information

Figure S1.

Figure S2.

Figure S3.

Appendix S2.

References

- 1. Comerota AJ, Gravett MH. Do randomized trials of thrombolysis versus open revascularization still apply to current management: what has changed? Semin Vasc Surg 2009; 22: 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kessel DO, Berridge DC, Robertson I. Infusion techniques for peripheral arterial thrombolysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; (1)CD000985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robertson I, Kessel DO, Berridge DC. Fibrinolytic agents for peripheral arterial occlusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; (12)CD001099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Earnshaw JJ. Acute ischemia: evaluation and decision making In Rutherford's Vascular Surgery (8th edn), Cronenwett JL, Johnston KW. (eds). Saunders, Elsevier: Philadelphia, 2013; 2518–2526. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heilmann C, Schmoor C, Siepe M, Schlensak C, Hoh A, Fraedrich G et al Controlled reperfusion versus conventional treatment of the acutely ischemic limb: results of a randomized, open‐label, multicenter trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2013; 6: 417–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baril DT, Ghosh K, Rosen AB. Trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of acute lower extremity ischemia in the United States Medicare population. J Vasc Surg 2014; 60: 669–677.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grip O, Wanhainen A, Acosta S, Björck M. Long‐term outcome after thrombolysis for acute lower limb ischaemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2017; 53: 853–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berridge DC, Kessel DO, Robertson I. Surgery versus thrombolysis for initial management of acute limb ischaemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; (6)CD002784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Palfreyman SJ, Booth A, Michaels JA. A systematic review of intra‐arterial thrombolytic therapy for lower‐limb ischaemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2000; 19: 143–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grip O, Kuoppala M, Acosta S, Wanhainen A, Åkeson J, Björck M. Outcome and complications after intra‐arterial thrombolysis for lower limb ischaemia with or without continuous heparin infusion. Br J Surg 2014; 101: 1105–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The STILE Investigators. Results of a prospective randomized trial evaluating surgery versus thrombolysis for ischemia of the lower extremity . The STILE trial. Ann Surg 1994; 220: 251–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Earnshaw JJ, Whitman B, Foy C. National Audit of Thrombolysis for Acute Leg Ischemia (NATALI): clinical factors associated with early outcome. J Vasc Surg 2004; 39: 1018–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ravn H, Bergqvist D, Björck M; Swedish Vascular Registry . Nationwide study of the outcome of popliteal artery aneurysms treated surgically. Br J Surg 2007; 94: 970–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Troëng T, Malmstedt J, Björck M. External validation of the Swedvasc registry: a first‐time individual cross‐matching with the unique personal identity number. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008; 36: 705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Venermo M, Lees T. International Vascunet validation of the Swedvasc registry. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2015; 50: 802–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AK, Ljung R, Michaëlsson K, Neovius M et al Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2016; 31: 125–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C et al External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rutherford RB, Baker JD, Ernst C, Johnston KW, Porter JM, Ahn S et al Recommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia: revised version. J Vasc Surg 1997; 26: 517–538. [Erratum in: J Vasc Surg 2001; 33: 805.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med 2011; 30: 377–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. VanderWeele TJ, Hernán MA, Robins JM. Causal directed acyclic graphs and the direction of unmeasured confounding bias. Epidemiology 2008; 19: 720–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ouriel K, Shortell CK, Deweese JA, Green RM, Francis CW, Azodo MV et al A comparison of thrombolytic therapy with operative revascularization in the initial treatment of acute peripheral arterial ischemia. J Vasc Surg 1994; 19: 1021–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ouriel K, Veith FJ, Sasahara AA. Thrombolysis or peripheral arterial surgery: phase I results. TOPAS Investigators . J Vasc Surg 1996; 23: 64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ouriel K, Veith FJ, Sasahara AA. A comparison of recombinant urokinase with vascular surgery as initial treatment for acute arterial occlusion of the legs. Thrombolysis or Peripheral Arterial Surgery (TOPAS) Investigators . N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 1105–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van den Berg JC. Thrombolysis for acute arterial occlusion. J Vasc Surg 2010; 52: 512–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL et al; American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology; Society of Interventional Radiology; ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines . ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Associations for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease) –summary of recommendations. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2006; 17: 1383–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Baril DT, Patel VI, Judelson DR, Goodney PP, McPhee JT, Hevelone ND et al; Vascular Study Group of New England . Outcomes of lower extremity bypass performed for acute limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg 2013; 58: 949–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hynes BG, Margey RJ, Ruggiero N II, Kiernan TJ, Rosenfield K, Jaff MR. Endovascular management of acute limb ischemia. Ann Vasc Surg 2012; 26: 110–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gupta R, Hennebry TA. Percutaneous isolated pharmaco‐mechanical thrombolysis–thrombectomy system for the management of acute arterial limb ischemia: 30‐day results from a single‐center experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2012; 80: 636–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ravn H, Björck M. Popliteal artery aneurysm with acute ischemia in 229 patients. Outcome after thrombolytic and surgical therapy. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2007; 33: 690–695. [Erratum in Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2007; 34: 251.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1.

Figure S2.

Figure S3.

Appendix S2.