Abstract

Montana, a large and rural U.S. state, has a motor vehicle fatality rate almost double the national average. For young adults, the alcohol-related motor vehicle fatality rate in the state is almost three times the national average. Yet little research has explored the underlying reasons that young people in rural areas drink and drive. Drawing from the theory of triadic influence (TTI) and a series of qualitative focus group discussions, the current study examined how aspects of the landscape and culture of rural America promote and hinder drinking and driving among young people. In 2015 and 2016, 72 young adults (36 females) aged 18–25 years old (mean age = 20.2) participated in 11 semi-structured focus groups in 8 rural counties in Montana. Discussions were transcribed, and two reviewers independently coded text segments. Themes were identified and an inductive explanatory model was created. The results demonstrated that aspects of the social context (e.g., peer pressure and parental modeling), rural cultural values (e.g., independence, stoicism, and social cohesion), and the legal and physical environment (e.g., minimal police presence, sparse population, and no alternative transportation) promoted drinking and driving. The results also identified salient protective factors in each of these domains. Our findings demonstrate the importance of examining underlying distal determinants of drinking and driving. Furthermore, they suggest that future research and interventions should consider the complex ways in which cultural values and environmental factors intersect to shape the risky health behaviors of rural populations.

Keywords: rural populations, alcohol, drinking and driving, driving under the influence, young adults, adolescents

1. Introduction

Motor vehicle crashes are one of the leading causes of preventable death in the United States. Although rates of motor vehicle fatalities have generally declined over time, this decline has stagnated in recent years, and deaths remain especially high among certain at-risk groups, such as rural populations (National Center for Statistics and Analysis, 2017). Stark disparities in rural–urban traffic fatalities contribute to the shorter lifespan of rural residents (Singh and Siahpush, 2014). Compared to urban areas, the motor vehicle fatality rate is 2.6 times higher in rural areas of the United States (National Center for Statistics and Analysis, 2017). Even within non-metropolitan areas, disparities are substantial and risk increases with rurality. For example, in the Western United States, age-adjusted passenger vehicle–occupant death rates in 2014 were 3.9 (per 100,000 people) in the largest metropolitan counties, 6.4 in smaller metropolitan counties, 18.0 in rural counties overall, and 40.0 in completely rural counties (Beck et al., 2017).

Similar to rural residents, young adult drivers are at heightened risk for motor vehicle fatality for various reasons, including their inexperience, underdeveloped cognitive capabilities, and personality characteristics (Bates et al., 2014; Cassarino and Murphy, 2018; Shope, 2006; Shope and Bingham, 2008). Furthermore, young people often engage in fewer traffic safety behaviors (e.g., seatbelt use) and more risky driving behaviors (e.g., speeding). Another critical aspect that puts young people at risk is their willingness to drive after drinking alcohol, a well-known contributor to motor vehicle crashes and fatalities. Substance use and drinking and driving1 increase across adolescence and peak during young adulthood (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016). In 2015, 13.8% of young adults 18–25 years old reported having driven under the influence of alcohol in the past year (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016). Research has demonstrated that young people in rural areas are more likely to engage in high-intensity binge drinking, consecutively consuming 15 or more drinks (Patrick et al., 2013). As a result, young people in rural areas may be especially vulnerable to alcohol-related crashes because of their high-intensity drinking in addition to factors related to their residential location. Research has shown that rural–urban differences in motor vehicle fatalities are particularly large among young drivers (Zwerling et al., 2005); therefore, identifying the reasons that rural young people drink and drive is critical to preventing this behavior and associated motor vehicle crashes.

To understand factors that encourage and discourage drinking and driving, we had group discussions with young adults in rural Montana. Large and sparsely populated, Montana has the highest percentage of rural residents (34.7%) of any U.S. state (Croft et al., 2018) and a motor vehicle fatality rate nearly double the national average (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2017). The rate of young adults in Montana killed in crashes involving alcohol is approximately 3 times the national average (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Previous research has examined the activities and situations when young adults drive drunk in rural Montana (Rossheim et al., 2018); however, little attention has been given to the underlying social, cultural, and environmental conditions that shape drinking and driving among rural young adults. Therefore, in the current study, we examined reasons for and against drinking and driving among young adults in Montana and explored how these reasons were embedded in the rural context.

1.1. Rurality and The Theory of Triadic Influence

Rurality is a multifaceted construct (Hart et al., 2005) that can be defined by demographic aspects (e.g., population density), economic factors (e.g., reliance on few industries), and sociocultural factors (e.g., high social cohesion). Due to persistent health disparities in rural populations, some scholars have referred to rurality as a fundamental cause of health and disease (Lutfiyya et al., 2012). Research on rural populations is sparse, so there is a critical need to understand how and why residing in a rural area may lead to negative health behaviors like drinking and driving (Hartley, 2004). To understand the multitude of ways that rural residence can influence drinking and driving behaviors, the comprehensive framework known as the theory of triadic influence (TTI) is useful. According to the TTI, health behaviors such as drinking and driving are determined by multiple streams of influence including intra-personal influences, inter-personal social influences, and cultural and environmental influences (Flay et al., 2009). Each of these streams contains substreams (i.e., cognitive/rational and affective/emotional) and different levels of causation. Underlying causes shape causally proximate or immediate factors (e.g., attitudes and beliefs) that, in turn, lead individuals to try a behavior.

The current study focused on upstream social, cultural, and environmental influences within the TTI. We explored how distal determinants in these domains shaped rural young people’s attitudes and beliefs about drinking and driving. Attending to underlying distal causes is important because they have the “greatest and longest-lasting influence” on health behavior (Flay et al., 2009, p. 457). In addition, it is important to understand cognitions related to drinking and driving given the previous research demonstrating that personal attitudes and beliefs (Beck, 1981; LaBrie et al., 2011; McCarthy et al., 2007), perceptions of harms (Bingham et al., 2007; Fairlie et al., 2010; Morris et al., 2014), and perceived approval from friends (Bingham et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008; Kenney et al., 2013) predict drinking and driving.

Although quantitative studies dominate the research on drinking and driving beliefs and perceptions, qualitative studies are particularly well suited to elucidating behavioral processes and explaining how actions unfold and are shaped by the contexts in which they occur. Previous qualitative work about drinking and driving has focused largely on offenders convicted of driving under the influence (DUI) (Eckberg and Jones, 2015; Fynbo and Jarvinen, 2011; Watters and Beck, 2016), with less research examining perceptions among young adults in the general population. One important exception is work by Nygaard et al. (2003), who interviewed 44 late adolescents in California to understand whether expectancies, control beliefs, and normative beliefs influenced drinking and driving. Their results underscored the importance of normative beliefs, but the study did not focus on environmental or cultural contextual factors that shape DUI behavior.

1.2. Study Aims

In the current study, we addressed two specific aims. First, we explored the reasons that young adults drink and drive in rural areas. Second, we sought to identify the protective factors that deter young people in these areas from drinking and driving. Our aims were shaped by social ecological perspectives; thus, we sought to identify individual-, peer-, family- , and community-level risk and protective factors as to inform intervention and prevention strategies for rural populations.

2. Method

2.1. Procedure

In 2015 and 2016, we conducted 11 focus group discussions in 8 non-metropolitan Montana counties (counties with population clusters fewer than 50,000 people). Counties were purposely selected to include northern, western, and eastern regions of the state to gain the perspectives of young people from diverse regions. Furthermore, the population densities of the areas were considered; populations of the towns where the focus groups were conducted ranged from less than 500 people to approximately 40,000. Given the small size of many of these towns, we used a convenience sampling method; study participants were identified through word-of-mouth, social media websites, and posted flyers.

Semi-structured focus groups were chosen to generate discussions and capture diverse opinions about drinking and driving (Krueger and Casey, 2015). These groups occurred at public meeting rooms within libraries, county offices, or colleges. A female in her early 30s conducted each focus group. Participants gave written informed consent, completed a demographic survey, and discussed various topics related to drinking and driving. To promote honest responses, participants were instructed to think about “young people your age” (e.g., “What are some of the reasons that young people your age drink and drive?”). This approach has been used previously to encourage honest answers in studies with young people involving other sensitive topics (Danton et al., 2003; Patrick et al., 2010). Data collection continued until a point of saturation had been reached; that is, little new information was being gleaned from additional groups (Krueger and Casey, 2015). Food was provided and participants were compensated $20. The ethics board at Montana State University approved all study protocols.

2.2. Participants

A total of 72 young adults participated in the study. The focus group discussions had a mean of 6.5 people (SD = 2.6) per group. Table 1 summarizes information about the participants and the location of the focus groups. Young adults ranged in age from 18 to 25 years old. About one-half of participants were female (51%), and many participants were enrolled in college (63%) and/or employed (69%). Most participants (92%) were non-Hispanic white, reflecting the sampled counties. Nearly all participants (94%) had consumed alcohol in their lifetime, and two-thirds (66%) reported alcohol consumption in the 30 days prior to being interviewed.

TABLE 1.

Focus Group Location and Composition

| Region Characteristics | Participant Characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population of Town | Region of MT | N | Gender (men, women) | Age Range (in years) | Drive > 50 Miles per Week? | Focus Group No. |

| <500 | East | 6 | 2m, 4w | 18–25 | 6/6 yes | 3 |

| <500 | East | 7 | 3m, 4w | 18–23 | 7/7 yes | 4 |

| 1,200 | South Central | 3 | 2m, lw | 18–20 | 1/3 yes | 11 |

| 1,200 | West | 4 | lm, 3w | 18–20 | 4/4 yes | 5 |

| 3,200 | North | 9 | 5 m, 4w | All 18 | 9/9 yes | 9 |

| 4,500 | West | 8 | 3m, 4w | 18–24 | 6/7 yes | 7 |

| 10,000 | North | 5 | 3m, 2w | 18–20 | 3/5 yes | 10 |

| 35,000 | South Central | 11 | 9m, 2w | 18–24 | 7/11 yes | 8 |

| 42,000 | Southwest | 9 | 4m, 5w | 19–25 | 8/9 yes | 1 |

| 42,000 | Southwest | 3 | lm, 2w | 20–22 | 1/3 yes | 2 |

| 42,000 | Southwest | 7 | 2m, 5w | 20–24 | 3/7 yes | 6 |

Notes: Population sizes are approximate. One participant in focus group 7 arrived late and did not complete the survey. N = 72.

2.3. Data Analysis

Discussions were audio recorded and subsequently professionally transcribed verbatim. Figure 1 presents a flow chart of our analysis process. The eclectic coding approach that was used included structural and descriptive coding as well as data theming (Saldaña, 2012). First, co-authors read through the transcripts and created a list of preliminary descriptive topics. Second, two coders structurally coded the text (i.e., categorized text segments by the research questions they addressed) and finalized a codebook of factors that encourage and discourage drinking and driving. Third, two independent reviewers completed descriptive coding; when discrepancies occurred, coded segments were reconciled. With the assistance of NVivo version 11 (QSR International, 2015), the resulting data were analyzed via code sorting, memoing, and concept mapping. These tools enabled the coauthors to identify emergent patterns and themes and create an explanatory model.

FIGURE 1.

Analytical Process

3. Results

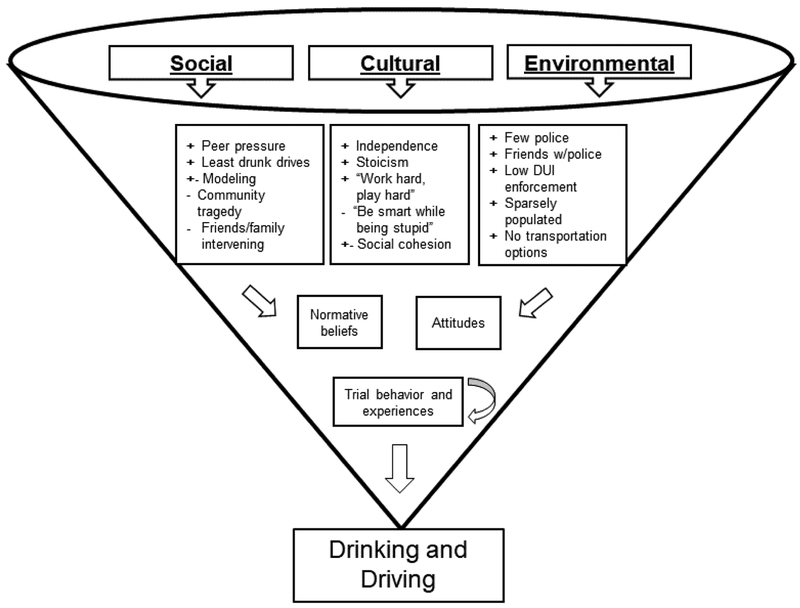

Young adults described how social interactions, cultural values, and environmental factors intersected to influence drinking and driving in rural areas. From the discussions, and drawing from TTI, we inductively developed a model to help explain drinking and driving behaviors in the rural context (Figure 2). At the top of the figure are the three streams of influence that shape drinking and driving in rural areas: social, cultural, and environmental. Social factors are relationships and interactions with peers, parents, and other meaningful adults. Cultural factors are the information, values, and ideals that young people gain from living in a rural context. Environmental factors include aspects of the physical environment itself as well as interactions with broader institutions (e.g., legal and religious institutions). Underneath each of the three categories are examples of risk factors (i.e., those that encourage drinking and driving, denoted with a + sign) and protective factors (i.e., those that discourage the behavior, denoted with a − sign). The figure is funnel shaped to emphasize that these distal risk and protective factors influence more proximal factors, such as individual attitudes and beliefs. In turn, these attitudes and beliefs lead young people to experiment with drinking and driving. Positive trial experiences reinforce the behavior, whereas negative trial experiences extinguish it.

FIGURE 2.

Reasons For and Against Drinking and Driving: An Explanatory Model Generated from Discussions with Rural Young Adults

Notes: + indicates a positive association with driving after drinking (i.e., risk factor), − indicates a negative association with driving after drinking (i.e., protective factor).

3.1. Social Influences: Risk Factors

Peers had a strong influence on drinking and driving beliefs. Much of the time, friends inadvertently caused drinking and driving by encouraging each other to binge drink. One participant noted, “If you don’t drink, I mean, that’s kind of unacceptable, right, in a rural town. There is this kind of push to be drinking, whether you are 15 or you’re 50” (female, FG 3). At other times, the pressure was explicitly related to driving. This would occur when a group of friends had been drinking alcohol and no one was sober enough to drive. As one participant described, “They’re just like, just do it, you’re fine. Just drive. Even if you feel like you’re not okay to drive, your friends might just make you feel uncomfortable to the point of where you’re like, ‘I’ll just drive’” (female, FG 1). There was an expectation that, to maintain positive peer relationships and promote safety, the “least drunk” person should drive, regardless of his or her level of intoxication.

The behavior of older family members also influenced drinking and driving beliefs. Some participants described childhood experiences riding as a passenger with a parent who had been drinking. One noted, “Your parents, even when you’re little, they’d have god knows how many, and you’d have to go home. It’s not like you could say, ‘No, I’m driving,’ because that’s not acceptable when you’re little!” (female, FG 3). This participant reflected on her exposure to riding with an intoxicated parent as a child and how her subordinate position made her unable to intervene and protect herself from the dangerous behavior. Another participant noted, “When I was a kid, I remember my dad driving home from the bar with a beer wide open, just drinking on the way home. And, it’s just, they’ve been a part of this culture for so long and they’ve been doing it for so long… I think they think they’re good drunk drivers is how I understand it” (male, FG 3). Children who saw their parents and grandparents drink and drive without negative consequences were thought to be more likely to engage in the behavior themselves. The intergenerational transmission of drinking and driving that occurred in families was described as a persistent “cycle.”

There was a perception that individuals in the most rural areas held the most positive attitudes toward drinking and driving. One participant described this: “I was raised, ‘Drinking and driving is the devil. You never do it. You’re disowned as my son if you do it.’ Where for you guys, in rural [areas], it’s like, ‘Oh, yeah, I’m gonna have a beer in the car when I drive you to soccer practice’” (male, FG 6). Although all participants were from non-metropolitan areas, this participant reinforces the idea that the behavior was perceived to be more common and socially acceptable in the most rural areas of the state.

3.2. Social Influences: Protective Factors

The risk of harming others was the main deterrent to drinking and driving and was brought up in all focus groups. Other consequences seemed to pale in comparison to the possibility of harming someone else. One participant described this: “What mind boggles me, though, is that some people don’t even stop to think. Like how can you put them [other people] in danger?” (female, FG 7). Several participants described how their upbringing and messages from parents led to a moral opposition to drinking and driving. One noted, “It has to do with morals, too. I mean, if you were brought up believing that you just don’t drink and drive, it’s not something that you do” (female, FG 4). Young adults modeled their parents’ behaviors; those whose parents abstained from alcohol or modeled safe drinking behaviors (without driving) were thought to be at lower risk for drinking and driving themselves. Participants noted that their parents “would just be straight up disappointed” (female, FG 6) if they were cited for a DUI, and this fear of disappointment and shame deterred them from engaging in the behavior.

Some young people described changing perspectives after someone they knew crashed because of drinking and driving. A community tragedy or well-known drunk driving incident served as an illustrative example of why not to drink and drive. These tragedies were especially salient in small rural areas where participants knew about and discussed specific tragic incidents. However, the impact of a community tragedy on drinking and driving was often short-lived. One participant described this phenomenon: “One of the toughest parts with a tragedy that happens, for possibly, two, three years, I don’t know how long, however [long] people take to deal with the tragedy, I mean, it disappears” (male, FG 3). Another participant agreed: “When Jake rolled his pickup with me and him and Jarrett, I was totally against drinking and driving for a solid year, but I got over that” (female, FG 3). Thus, the decrease in drunk driving resulting from community tragedies may fade over time.

Another strong deterrent to drinking and driving was the potential to harm oneself, although this was perceived to be less heinous than harming others. Oftentimes, participants seemed to believe that it was an individual’s right to put his or her own life in danger, in line with cultural values about self-determination (discussed later). One noted, “If I do something dumb as long as it’s only affecting me, okay, fine, I chose to put that on myself” (female FG 1). Sometimes, however, discussions of harming oneself gravitated toward family and friends who would be affected. Some young adults refrained from drinking and driving because they recognized that harming themselves physically would result in emotional injury to others.

At times, family and peers actively prevented drunk driving by using various intervention strategies. One example was the “key bowl,” in which the host of a house party collected car keys from attendees to ensure that they did not drive home after drinking. More frequently, young adults discussed how they encouraged friends to avoid drunk driving: “I totally guilt-trip all my friends, too, if they try and drink and drive. It works pretty well” (female FG 6). Young people spoke favorably when they reflected on this monitoring of friends and younger family members at drinking events.

3.3. Cultural Influences: Risk Factors

Our discussions with young people suggested that drinking and driving in Montana is rooted in rural cultural values such as independence, stoicism, and the “work hard, play hard” ethos. Independence and self-reliance are highly regarded in rural Montana, and vehicles embody these values as they provide a source of autonomy in daily life. As one participant noted, “We don’t walk anywhere in Montana; we drive everywhere” (female, FG 3). Trucks and cars are “a status symbol” that give young people the freedom to attend and leave activities and situations without relying on someone else. When asked about the reasons for drinking and driving, one participant noted, “I think a lot of people that I know don’t really want to have to burden other people.… They want to be able to take care of themselves” (female, FG 6). This desire for self-sufficiency would sometimes lead young adults to drink and drive instead of staying the night at a friend’s house or asking for a ride home.

Furthermore, a respect for independence and autonomy caused some young people to feel as though they could not speak out or intervene when another community member decided to drink and drive:

Male, FG 4: I couldn’t go to one of the ranchers and say, “Hey, don’t drive drunk.” If I did that, I’d get laughed at and walk away, you know?

Female FG 4: Or punched.

Discussions highlighted the social norms dictating that young adults could not interfere with the behaviors or lives of other community members—especially those who were older, wealthier, or held certain occupations (e.g., ranchers). Instead, other community members overlooked or condoned drinking and driving out of a strong belief in individual rights and autonomy.

Being in control of one’s behaviors and emotions—a characteristic that some might call stoicism (although the definition is debated, see Moore et al., 2013)—was also highly valued in rural areas. Although heavy drinking was valued, appearing intoxicated indicated an inability to maintain one’s composure. Thus, young people simultaneously received pressure to drink in excess but not appear intoxicated. Asking for a ride or spending the night at a friend’s house was seen as irresponsible because it indicated overconsumption. This was explained: “There’s this perception that if you’re handing over the keys… then you’re admitting that you can’t handle your alcohol. It’s not so much that you’re being safe or smart, it’s just that you’re out of control” (female, FG 3). Participants noted that taking the “safe route” was frowned upon, and thus they would try to “fake sober” or “put a straight face on” and drive to avoid judgment.

Also at the core of relevant rural values was the importance of working hard. Adults in rural areas considered work to be central to their identity. One young adult noted, “We’re probably super-biased against urban people—like, ‘We work so much harder!’” (female, FG 3). Oftentimes this work deserved rewards in terms of excessive alcohol consumption (i.e., they “work hard” and “play hard”). Driving often occurred after “playing hard” because of the need to return home. One participant described how this behavior may have come about:

It’s also with that “play hard, work hard” [mentality] so, you know, you have to be home, 6:00 a.m., to be on the baler, and you’re not gonna spend the night at your friend’s house—you know, you gotta get home. And so I think that, I guess in my eyes that may have been how this perception in this culture kind of bred (male, FG 3).

Social cohesion, or having a tight-knit community, was also valued in rural areas. This characteristic was often protective, but cohesion and monitoring could also, paradoxically, lead to drinking and driving. Participants noted that in very rural tight-knit communities, young people sometimes hesitated to leave their car or walk somewhere because they feared that community members would gossip. Community members would discuss, for instance, whose car was left overnight at the bar or at another person’s house in town. Individuals who lived in town did not want to walk home because they feared being recognized while intoxicated. One female noted, “Since it’s a small town, then if one person sees you, the word gets around and then you’re the town drunk” (female, FG 9). The discussions made it clear that having a reputation as an upstanding community member was especially critical in small towns, and the desire to maintain that reputation was, under certain circumstances, a motivation for drinking and driving.

3.4. Cultural Influences: Protective Factors

Rural values shaped reasons against drinking and driving. In multiple focus groups, participants described a cultural mindset that individuals should “be smart while being stupid.” This idea stemmed from the consensus that risky behaviors—including drinking to excess—were common among rural young people. However, they were encouraged to take safety precautions to reduce the likelihood of negative consequences. As one participant described: “My mom has told me since junior high, ‘Be smart when you’re being stupid.’… So you’re being stupid when you’re getting drunk, so be smart and have a ride, or stay where you are and call somebody to come get you” (female, FG 4). It was assumed that young adults would engage in risky behavior such as heavy episodic drinking, but they were urged to take precautions to mitigate alcohol-related consequences.

High levels of social cohesion in rural communities and the idea that community members “look out for each other” also protected against drinking and driving. Adults and older family members would take care of young people who had consumed too much alcohol and make sure that they were safe and did not drive anywhere. Furthermore, community members in rural areas monitored each other’s behaviors and actions, and news of drunk driving incidences spread quickly to the entire community. Friends, family members, and employers would all learn about a DUI. One participant explained, “I think the shame is even more so because if you do get it [a DUI] in a rural area, a small town, everyone knows. Not figuratively everyone, literally everyone knows. So I feel like that could be even more of a deterrent” (male, FG 6). Other participants explained how you “can’t hide” or “escape” from the watchful eyes of community members in rural areas. Furthermore, they noted that young adults feared that a DUI could destroy their reputation as well as their family’s reputation. One participant noted, “If you were to go out and get a ticket for something serious, everybody would know about it… [and] if you were to hurt somebody while drinking and driving, you would essentially be shunned in a way from the town” (male, FG 11). Thus, young people feared legal consequences and harming others, but they also feared the stigma that accompanied these consequences in rural areas.

3.5. Legal Environment: Risk Factors

Interactions with law enforcement also influenced attitudes and expectancies related to drinking and driving. Participants noted that rural areas had fewer law enforcement officers and that these officers often had large areas to patrol. Thus, getting caught drinking and driving was perceived to be less likely in rural areas than in urban areas. One participant described the environment where he lived: “The police officers have to go all throughout the county, and there’s four towns that they have to patrol, and there aren’t that many deputies… So it’s, I feel like it’s less of running into the police, or being pulled over by a police officer” (male, FG 5). Also, young adults typically knew the sheriff in very rural areas. Some participants mentioned that this relationship could protect them from being cited for a DUI. One noted, “Small town. The cops know everyone. I know four people in my family, and a bunch of friends that have gotten pulled over super-drunk and wrecked, and somehow they don’t get a DUI. They just, like, slip it under the rug” (female, FG 6). Thus, there is a perception that some law enforcement officers in rural areas are “friends with everyone” and as a result give fewer tickets for driving under the influence of alcohol.

At the same time, some underage participants did fear getting caught by law enforcement, and, surprisingly, this fear sometimes promoted drinking and driving. For instance, minors would drink in clandestine locations because they feared getting cited for a minor in possession (MIP), and then they would have to drive home. Furthermore, to avoid getting an MIP, underage youth reported driving while drinking on backroads or country roads to avoid detection by police officers and others. Oftentimes, youth in rural areas knew where the police officer(s) would patrol, and thus driving the dirt roads outside of town (off of the patrol route) was viewed as a safe strategy to avoid detection.

3.6. Legal Environment: Protective Factors

Although some participants were not concerned with legal consequences associated with drinking and driving, as they did not think them likely, others noted that they did fear these legal consequences. Receiving a DUI was feared for a variety of reasons, including the risk of jail, the loss of a driver’s license, and the cost (e.g., legal costs, higher insurance rates, and replacing damaged property). In addition, young adults worried about damaging their career or education. One participant noted, “A lot of people would lose their jobs too if they got DUIs.… I know I would. My boss just doesn’t really put up with it. If you don’t have a license, you’re not gonna be worth much to him” (male, FG 10). Participants were also concerned that a DUI would inhibit their ability to secure a competitive job that required a background check. Likewise, other participants described high educational aspirations and worried that a DUI could prevent them from gaining admission into institutions of higher education or securing financial aid.

3.7. Physical Environment: Risk Factors

Various aspects of the rural environment—including the low population density and limited alternative transportation options—shaped drinking and driving opportunities for rural residents. Participants noted that it was common in rural areas to be one of the only drivers on the road and that pedestrians were virtually nonexistent. One participant stated, “You’d be kind of afraid to run into something, like, in New York—whereas here, you’re not gonna run into anything but a fence!” (female, FG 3). Another participant explained that drinking and driving was more dangerous in urban areas because “there’s more people to be endangered” (male, FG 7). Furthermore, participants often thought that they knew the roads quite well, having traveled them for years. This familiarity, and the low population density, gave them a sense of confidence when driving, regardless of whether or not they had been drinking. The lack of alternative transportation options was another common reason provided for drinking and driving. One participant described the constraints of living in a rural environment saying that in “a big town you have other options, like you can call Uber or someone else to get you. I mean, in a small town, you can’t do that” (female, FG 9). Participants thought that there was a culture of taking advantage of private and public transportation options in urban areas that was not present in rural areas. Alternative transportation seemed to be one of the most effective strategies to protect against drinking and driving in some communities; however, public or private options were typically unavailable and viewed as unviable in very rural areas. In these sparsely populated areas, even asking a friend for a ride home could be viewed as an unreasonable request given the long distances that often separate friends’ houses.

3.8. Physical Environment: Protective Factors

In general, participants thought that the rural environment facilitated drinking and driving; nonetheless, they did give examples of the dangers that existed in the rural environment that made them hesitant to drink and drive (e.g., deer and other animals on the road, curvy and narrow mountain roads, highways that encouraged speeding). One participant described how the lack of people on the roads, and the corresponding delays in detecting motor vehicle crashes, could also deter drinking and driving. He noted, “getting into an accident with nature and having something happen and not being found is kind of a terrifying thought to me, which is why I would never drink and drive anywhere out of town” (male, FG 8). Although critically important, this viewpoint was seldom voiced in the focus groups.

3.9. Trial Behaviors and Experiences

Participants described how previous experiences could encourage or discourage drinking and driving.

One male participant explained how drinking and driving without negative consequences promoted subsequent drunk driving episodes:

Another thing is familiarity—they’ve done it before, like ‘Oh, I drive drunk all the time. I do it every weekend; I can do it tonight.’… They say they’ve done it before so it’s like ‘I’m confident I can just get in my car and go home. It’ll just be like all the other times I’ve done it.’ I’ve seen that a lot. That’s probably the most common thing I see with my friends. They’re just like ‘I’ve done it before, might as well just do it again’ (male, FG 8).

As is evident in this quote, when young adults drink and drive without consequences, they gain confidence in their ability to drive while intoxicated and are more likely to repeat the behavior in the future. At the same time, negative experiences associated with drinking and driving lead some young adults to discontinue the behavior. One participant stated, “I just think the fact like knowing that you can harm somebody else in that situation made me stop… ‘cause I almost did” (male, FG 8). Participants explained how an automobile crash could lead individuals to avoid drunk driving, noting that “a good scare” could stop the behavior. These descriptions make it clear that, in line with TTI, experiences with drinking and driving trial behaviors served to reinforce or extinguish the behavior (Flay et al., 2009).

3.10. Attitudes and Normative Beliefs

Taken together, the various aspects of the rural context—including social pressures and modeling, cultural values, legal environment, and sparse populations—shaped attitudes and beliefs about drinking and driving. As one participant described, drinking and driving was “just accepted. It’s part of life” in rural areas (female, FG 4). In these areas, the negative outcomes associated with drinking and driving (e.g., harming someone else, getting a DUI) were perceived to be minimized and therefore attitudes toward the behavior were more favorable.

4. Discussion

Despite the high rates of drinking and driving and traffic crash fatalities in rural areas, relatively little is known about how aspects of the rural context may shape decisions to drink and drive. Therefore, discussions with 72 young adults in 11 focus groups were used to inductively create a conceptual model detailing how distal social, cultural, and environmental factors in rural areas influence drinking and driving.

In creating our conceptual model and organizing our results, we drew from the theory of triadic influence (Flay et al., 2009). However, given our interest in context as well in the distal determinants of drinking and driving behavior, we limited our focus to social, cultural, and environmental factors. We did not discuss intra-individual influences, which have received much attention in other literature (Arnett, 1990; Iversen and Rundmo, 2002; Patil et al., 2006). In our focus groups, distal intra-individual determinants of driving after drinking (e.g., genetic or hormonal differences or stable personality traits) were not discussed frequently, although participants did periodically refer to drunk drivers as “selfish,” “thoughtless,” or “overconfident.”

In line with previous research, our results emphasized the influence of parents, peers, and community members on drinking and driving. Parental messages and strong parental relationships were viewed as protective, in line with prior work linking parental support (Sabel et al., 2004) and paternal monitoring (Li et al., 2014) to lower likelihoods of drinking and driving. At the same time, we described the ways in which parents and peers modeled and encouraged drinking and driving. Our descriptions are in line with previous quantitative research that has linked perceived peer drunkenness to impaired driving (Li et al., 2016) and work indicating that young people who have ridden with intoxicated peers and parents may be especially at risk for driving under the influence themselves (Leadbeater et al., 2008). Our study also described the role of community cohesion and monitoring. Although research has suggested a protective association between social cohesion and DUI (e.g., Sabel et al., 2004), our results demonstrated how social cohesion and monitoring could serve as risk factors for drinking and driving in addition to protective factors. That is, in a tight-knit community, a person might decide to drive drunk to preserve their reputation.

Our study further documented that cultural and environmental factors were salient to young adults. We identified particular values—individualism, maintaining control of one’s emotions and behaviors (or, stoicism), and a “work hard, play hard” ethos—that influenced everyday interactions of young people and shaped normative beliefs about drinking and driving. Although our explanatory model posits that cultural values shape young people’s attitudes and, in turn, these cultural values shape their behaviors, rural young people referred to the drunk driving behavior itself as “cultural.” The behavior was seen as persisting across generations and being tied to the rural context. Nonetheless, the mindset of “being smart while being stupid” resulted in some young people taking a harm-reduction approach by trying to minimize their negative alcohol-related consequences.

The rural environment—long, empty roads and limited alternative transportation options—also influenced young people’s views about the perceived harms associated with driving under the influence of alcohol. Our study demonstrated that young people thought that the minimal police presence and few drivers on the road in rural areas made the behavior less risky and thus more acceptable; the perceived risk of harms—such as a severe car crash or DUI receipt—were thought to be lower in rural areas than urban areas. Although the likelihood of hurting someone was perceived to be lower, participants were acutely aware of the social risks in the rural context that accompanied both choosing to drink and drive and choosing not to drink and drive. Previous research has negatively linked perceived harms to drinking and driving behaviors (Bingham et al., 2007; Fairlie et al., 2010; Morris et al., 2014); thus, it is useful to understand how young people weighed different risks (e.g., physical, social).

4.1. Future Research

This study assessed perceptions related to drinking and driving rather than actual individual behaviors because we expected that this approach would increase the accuracy of self-report in tight-knit communities. Furthermore, our conceptual model was based on young adults in rural Montana. Future qualitative research could explore determinants of drinking and driving in rural areas outside of Montana. In addition, quantitative approaches could be used to test the explanatory model and examine which components can be generalized to other rural areas. We would hypothesize, for instance, that risk and protective factors related to the physical environment and legal institutions might be consistent across rural areas, whereas particular cultural values might vary. Importantly, the specific risk and protective factors that we identified could be applied to and inform future research on other risky health behaviors among rural populations (e.g., tobacco and illicit drug use, seat belt use, etc.).

4.2. Informing Prevention Programs and Policies

By understanding the unique values, social pressures, and environmental risks that contribute to drinking and driving in rural communities, our findings may be used to inform prevention programs and policies. For instance, our findings about perceived risks are relevant. Although rural young people thought that harming others was unacceptable, they perceived harming oneself to be more permissible. Messages to reduce drunk driving among this population might, therefore, aim to increase perceived susceptibility of harming others (e.g., passengers) and emphasize the roles that rural young people play in the lives of others. Rural young people also explained how community tragedies change drunk driving behaviors in the short term; however, individuals subsequently revert to old behavioral patterns. In designing programs, researchers and prevention specialists should think about strategies to extend the effects of positive behavioral changes.

Our findings have implications for policies related to drinking and driving. The discussions suggest that at least some youth have a perception that “getting caught” is unlikely in rural areas; therefore, increasing enforcement (or at least the perception of enforcement) might be useful. Previous research indicates that DUI arrests are associated with reductions in alcohol-impaired fatalities; however, the association may be weaker in rural than in urban areas (Yao et al., 2016). Other evidence demonstrates that the effect of policies and enforcement varies across geographic areas. For instance, one study found that the impact of DUI-related policies depended on rates of alcohol-related traffic fatalities: In areas with high alcohol-related fatality rates (e.g., Montana), ex post regulations (e.g., license revocation and setting BAC limits) were more useful, whereas preventative measures were more effective in areas with low alcohol-related traffic fatality rates (Ying et al., 2013)(Ying, Wu, and Chang 2013). These findings emphasize that laws and policies are contextually embedded and their impact may depend on regional differences. Attending to local attitudes and beliefs may be especially important to develop programs and policies that are most effective at reducing risky and illegal behaviors. Our study, for instance, suggests that the unique relationships between police and the public in rural areas shape perceptions of DUI arrests. To be successful in these areas, programs would need to consider the strong relationships and tight-knit nature of these communities as well as the values held by their residents. Understanding the views of young people in rural areas is important given that the burden of harm caused by alcohol-related motor vehicle crashes falls disproportionately on rural residents (Czech et al., 2010; Zwerling et al., 2005), and young adults drink and drive at disproportionately higher rates (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016). The current study described how the beliefs and risky behaviors of rural young people are inextricably tied to the rural context. Attending to the underlying factors that shape normative beliefs and attitudes toward drinking and driving is critical to understand and ultimately reduce this behavior and associated alcohol-related motor vehicle crashes.

4.3. Conclusions

This study identified numerous ways in which features of the social setting, culture, and environment specific to rural areas encouraged or discouraged drinking and driving in young adults. By identifying these upstream determinants of drinking and driving stemming from the rural environment, the results of this study can inform future research and interventions targeting rural communities. Research is needed to develop evidence-based approaches to mitigate risks and bolster protective effects related to rural environments.

TABLE 2.

Underlying Influences on Drinking and Driving (DAD) in Rural Areas

| Description | Example Risk Factors | Example Protective Factors |

|---|---|---|

| SOCIAL: Interactions and relationships with peers, family, and community members | Peers encouraged one another to drink heavily. When no one was sober, the least drunk person was pressured to drive. Peers and parents modeled DAD; families transmitted the behavior intergenerationally. |

Friends, family, and community members monitored the behavior of young adults and intervened to stop DAD (e.g., by collecting car keys from party attendees or guilt tripping friends to not drive). Community tragedies (e.g., a friend dying in an alcohol-related car crash) deterred young people from DAD. |

| CULTURAL: Shared values and attitudes in rural areas |

Self-reliance and maintaining composure were valued, so asking for a ride when intoxicated was undesirable and could be a source of ridicule. In tight-knit communities, leaving one’s car overnight or walking home intoxicated could result in judgment or damage to one’s reputation as an upstanding community member, leading young people to DAD. |

Young people were encouraged by their parents to “be smart when you’re being stupid” and mitigate alcohol-related harms (e.g., by calling a friend for a ride). In tight-knit communities, everyone knows when someone receives a citation or harms another person while driving intoxicated. This fear of public shame deterred DAD. |

| ENVIRONMENTAL: Aspects of the physical environment and connections with larger institutions |

The perceived risk of harming someone else while driving intoxicated was low because of few other drivers on the road in rural areas. The perceived likelihood of getting caught DAD was low because rural residents often knew local law enforcement and a small number of officers patrolled large areas. |

Although the most rural areas did not have transportation options, some small towns had public buses. These buses were frequently used by young people to avoid DAD. Some rural young people feared legal consequences because they recognized that it could harm their careers or educational opportunities. |

Highlights.

Little is known about the reasons rural young people drink and drive.

11 focus groups were conducted with rural young adults (N=72) in Montana.

An inductive model for drinking and driving was created.

Social, cultural, and environmental factors promoted drinking and driving.

Unique aspects of the rural context shaped attitudes and beliefs.

FUNDING SOURCE

Research reported in this article was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers P20GM104417 and P20GM103474. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest:

none.

1We have opted to use the language of our participants, who typically referred to “drinking and driving” and “drunk driving.” Nonetheless, we recognize that some scholars may prefer alternative terminology such as driving after drinking (DAD) or “drink driving.”

REFERENCES

- Arnett J, 1990. Drunk driving, sensation seeking, and egocentrism among adolescents. Personal. Individ. Differ 11 6, 541–546. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(90)90035-P [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates LJ, Davey J, Watson B, King MJ, Armstrong K, 2014. Factors contributing to crashes among young drivers. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J 14 3, e297–e305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KH, 1981. Driving while under the influence of alcohol: Relationship to attitudes and beliefs in a college population. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 8 3, 377–388. doi: 10.3109/00952998109009561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck LF, Downs J, Stevens MR, Sauber-Schatz EK, 2017. Rural and urban differences in passenger-vehicle–occupant deaths and seat belt use among adults – United States, 2014. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. MMWR 66 17, 1–13. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6617a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham CR, Elliott MR, Shope JT, 2007. Social and behavioral characteristics of young adult drink/drivers adjusted for level of alcohol use. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 31 4, 655–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00350.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassarino M, Murphy G, 2018. Reducing young drivers’ crash risk: Are we there yet? An ecological systems-based review of the last decade of research. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav 56, 54–73. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2018.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016. Drunk driving state data and maps. Percentage of adults who report driving after drinking too much (in the past 30 days), 2012 [WWW Document]. URL https://www.cdc.gov/motorvehiclesafety/impaired_driving/states-data-tables.html (accessed 12.27.17).

- Chen M-J, Grube JW, Nygaard P, Miller BA, 2008. Identifying social mechanisms for the prevention of adolescent drinking and driving. Accid. Anal. Prev 40 2, 576–585. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft JB, Wheaton AG, Liu Y, Xu F, Lu H, Matthews KA, Cunningham TJ, Wang Y, Holt JB, 2018. Urban-rural county and state differences in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – United States, 2015. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 67 7, 205–211. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6707a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech S, Shakeshaft AP, Byrnes JM, Doran CM, 2010. Comparing the cost of alcohol-related traffic crashes in rural and urban environments. Accid. Anal. Prev 42 4, 1195–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danton K, Misselke L, Bacon R, Done J, 2003. Attitudes of young people toward driving after smoking cannabis or after drinking alcohol. Health Educ. J 62 1, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Eckberg DA, Jones DS, 2015. “I’ll just do my time”: The role of motivation in the rejection of the DWI court model. Qual. Rep 20 1, 130–147. [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie AM, Quinlan KJ, DeJong W, Wood MD, Lawson D, Witt CF, 2010. Sociodemographic, behavioral, and cognitive predictors of alcohol-impaired driving in a sample of U.S. college students. J. Health Commun. 15 2, 218–232. doi: 10.1080/10810730903528074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Snyder F, Petraitis J, 2009. The theory of triadic influence, in: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC (Eds.), Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. Jossey-Bass, New York, pp. 451–510. [Google Scholar]

- Fynbo L, Jarvinen M, 2011. “the best drivers in the world”: Drink-driving and risk assessment. Br. J. Criminol 51 5, 773–788. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azr067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hart LG, Larson EH, Lishner DM, 2005. Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am. J. Public Health 95 7, 1149–1155. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley D, 2004. Rural health disparities, population health, and rural culture. Am. J. Public Health 94 10, 1675–1678. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.10.1675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen H, Rundmo T, 2002. Personality, risky driving and accident involvement among Norwegian drivers. Personal. Individ. Differ 33 8, 1251–1263. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00010–7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney SR, LaBrie JW, Lac A, 2013. Injunctive peer misperceptions and the mediation of self-approval on risk for driving after drinking among college students. J. Health Commun. 18 4, 459–477. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.727963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, Casey MA, 2015. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 5th ed. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Kenney SR, Mirza T, Lac A, 2011. Identifying factors that increase the likelihood of driving after drinking among college students. Accid. Anal. Prev 43 4, 1371–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2011.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Foran K, Grove-White A, 2008. How much can you drink before driving? The influence of riding with impaired adults and peers on the driving behaviors of urban and rural youth. Addiction 103 4, 629–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Simons-Morton B, Gee B, Hingson R, 2016. Marijuana-, alcohol-, and drug-impaired driving among emerging adults: Changes from high school to one-year post-high school. J. Safety Res. 58, 15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Simons-Morton BG, Brooks-Russell A, Ehsani J, Hingson R, 2014. Drinking and parenting practices as predictors of impaired driving behaviors among U.S. adolescents. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 75 1, 5–15. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutfiyya MN, McCullough JE, Haller IV, Waring SC, Bianco JA, Lipsky MS, 2012. Rurality as a root or fundamental social determinant of health. Dis. Mon 58 11, 620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DM, Lynch AM, Pederson SL, 2007. Driving after use of alcohol and marijuana in college students. Psychol. Addict. Behav 21 3, 425–430. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A, Grime J, Campbell P, Richardson J, 2013. Troubling stoicism: Sociocultural influences and applications to health and illness behaviour. Health (N. Y.) 17 2, 159–173. doi: 10.1177/1363459312451179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris DH, Treloar HR, Niculete ME, McCarthy DM, 2014. Perceived danger while intoxicated uniquely contributes to driving after drinking. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 38 2, 521–528. doi: 10.1111/acer.12252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Statistics and Analysis, 2017. Rural/Urban Comparison of Traffic Fatalities: 2015 Data. (No. DOT HS 812 393), Traffic Safety Facts National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2017. Traffic safety facts: Montana. U.S Department of Transportation, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard P, Waiters ED, Grube JW, Keefe D, 2003. Why do they do it? A qualitative study of adolescent drinking and driving. Subst. Use Misuse 38 7, 835–863. doi: 10.1081/JA-120017613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil SM, Shope JT, Raghunathan TE, Bingham CR, 2006. The role of personality characteristics in young adult driving. Traffic Inj. Prev 7 4, 328–334. doi: 10.1080/15389580600798763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Palen L, Caldwell L, Gleeson S, Smith E, Wegner L, 2010. A qualitative assessment of South African adolescents’ motivations for and against substance use and sexual behavior. J. Res. Adolesc 20 2, 456–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00649.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, Martz ME, Maggs JL, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, 2013. Extreme binge drinking among 12th-grade students in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA Pediatr. 167 11, 1019–1025. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International, 2015. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software.

- Rossheim ME, Greene KM, Stephenson CJ, 2018. Activities and situations when young adults drive drunk in rural Montana. Am. J. Health Behav. 42 3, 27–36. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.42.3.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabel JC, Bensley LS, Van Eenwyk J, 2004. Associations between adolescent drinking and driving involvement and self-reported risk and protective factors in students in public schools in Washington State. J. Stud. Alcohol 65 2, 213–216. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J, 2012. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Shope JT, 2006. Influences on youthful driving behavior and their potential for guiding interventions to reduce crashes. Inj. Prev 12 Suppl 1, i9–i14. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.011874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shope JT, Bingham CR, 2008. Teen driving: Motor-vehicle crashes and factors that contribute . Am. J. Prev. Med., Teen Driving and Adolescent Health 35 3, Supplement, S261–S271. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Siahpush M, 2014. Widening rural–urban disparities in life expectancy, U.S., 1969–2009. Am. J. Prev. Med 46 2, e19–e29. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watters SE, Beck KH, 2016. A qualitative study of college students’ perceptions of risky driving and social influences. Traffic Inj. Prev 17 2, 122–127. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2015.1045063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Johnson MB, Tippetts S, 2016. Enforcement uniquely predicts reductions in alcohol-impaired crash fatalities. Addiction 111 3, 448–453. doi: 10.1111/add.13198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Y-H, Wu C-C, Chang K, 2013. The effectiveness of drinking and driving policies for different alcohol-related fatalities: A quantile regression analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 10 10, 4628–4644. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10104628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwerling C, Peek-Asa C, Whitten PS, Choi S-W, Sprince NL, Jones MP, 2005. Fatal motor vehicle crashes in rural and urban areas: decomposing rates into contributing factors. Inj. Prev 11 1, 24–28. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.005959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]