Abstract

Survivorship has become a significant topic within oncologic care. The tools and means by which the provision of survivorship care can be implemented and delivered are in development and are the focus of significant research oncology-wide. These tools and methods include innovations of survivorship care delivery, survivorship care plans, and improving communication among all stakeholders in an individual patient’s care as the means to elevate health-related quality of life. The merits of these survivorship care provisions in the field of neuro-oncology and its patients’ exigent need for more patient-centric care focused on living with their illness are discussed. Since 2014 there has been a mandate within the United States for adult cancer patients treated with curative intent to receive survivorship care plans, comprising a treatment summary and a follow-up plan, intended to facilitate patients’ care after initial diagnosis and upfront treatment. Several cancer-specific survivorship care plans have been developed and endorsed by health care professional organizations and patient advocacy groups. A survivorship care plan specific for neuro-oncology has been collaboratively developed by a multidisciplinary and interprofessional committee; it is endorsed by the Society for Neuro-Oncology Guidelines Committee. It is available as open access for download from the Society for Neuro-Oncology website under “Resources”: https://www.soc-neuro-onc.org/SNO/Resources/Survivorship_Care_Plan.aspx. Survivorship care offers an opportunity to begin directly addressing the range of issues patients navigate throughout their illness trajectory, an oncology initiative to which neuro-oncology patients both need and deserve equitable access.

Keywords: neuro-oncology, patient advocacy, patient care planning, quality of life, survivorship care planning

“The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.” —Sir William Osler

The etymology of “patient” stems from the Latin adjective patientem, “bearing, supporting, suffering, enduring, permitting,” reflecting the inherently experiential aspect of being an individual awaiting or under medical care. Disease, a pathophysiologic process, rather than illness, the patient’s experience of having disease, however, ultimately became the central focus of medicine. This is evident in the design of our health care systems, though the suffering remains. Models and processes of care focused on the patient experience have begun to receive renewed attention. Such efforts are especially notable within the oncology field, where the patient experience is particularly salient given the gravity of the diagnoses and severity of the treatments. Examples of these efforts include clinical trials focused on improving patient symptom reporting and symptom management during cancer treatment; initiatives to enhance provider–patient communication; efforts to better understand when and how end-of-life care can be addressed within patient–physician relationships, promoting the integration of palliative medicine with concurrent oncologic care from the beginning of a patient’s illness trajectory; and the initiatives of cancer patient survivorship and supportive care. In fact, randomized clinical trials investigating the implementation of early palliative care with concurrent standard oncologic care and systematic symptom monitoring during outpatient chemotherapy, respectively, were found to be efficacious in improving overall survival.1,2 Indeed, only 1 of the 7 drugs approved in 2016 for treatment of metastatic solid tumors reporting overall survival data, ranging in median survival advantages of 2 to more than 11 months, had a longer median survival difference than the overall survival increase reported in the patient symptom reporting study.3 This analysis conspicuously illustrates an enormous opportunity if not a mandate to incorporate the patient illness experience into the models and processes of care concurrent with tumor-directed treatments. To quote Dr Monika Krzyzanowska from her plenary discussion of Dr Basch’s symptom monitoring study at the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting 2017, “Managing symptoms during treatment is a fundamental aspect of our role as oncology clinicians, and hence this [Basch’s] trial is relevant to all of us in the oncology community regardless of what cancers we treat and where we practice.” As the value of patient-centered care has gained greater awareness within oncology, there is now commensurate interest in how, when, and where to make care patient centric.

Cancer survivorship arose as a cancer patient advocacy endorsed initiative to provide more patient-centered care across the illness and care trajectory. Although the clinical definition of cancer survivorship focused on disease-free survival for a minimum of 5 years may have oncologic utility, patient advocacy groups such as the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS) identified a need for language that more accurately captures patients’ experiences of living with cancer and beyond. The NCCS asserts that “an individual is considered a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis, through the balance of his or her life.” The United States’ National Cancer Institute (NCI) expanded the cancer survivor definition to include family members, friends, and caregivers, emphasizing the wide-ranging psychosocial impacts of a cancer diagnosis. Within the neuro-oncology community, we are acutely aware that “no evidence of disease” is not a realistic treatment goal for many of our patients, although we may recognize that they are survivors nevertheless—facing the illness as well as debilitating toxicities and side effects of cancer treatment. Thus, the language proposed by the NCCS and endorsed by the NCI is equally applicable to patients with central nervous system (CNS) tumors regardless of their prognosis or treatment status. While as a field we have been focused on finding efficacious tumor-directed treatment options, we may best serve patients and their families by fully embracing patient-centered care. To this end, we seek to highlight the need for patient-centered care provided in the context of survivorship care with a brief review of the literature pertaining to the range of survivorship issues faced by neuro-oncology patients and their families. We also discuss survivorship care plans as a tool for facilitating the provision of survivorship care, propose a possible conceptual framework for survivorship care in neuro-oncology, and offer specific recommendations to build an evidence base of efficacious supportive care interventions.

Living with a Primary Brain Tumor

Over the last decade, the neuro-oncology literature has clearly revealed the prevalence of multiple complex symptoms, needs, and concerns of patients with CNS malignancies throughout their illness trajectory. For instance, symptom report data from 621 patients diagnosed with primary brain tumors enrolled across 8 different clinical trials which included exploring symptom burden at any point in their care trajectory at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center disclosed more than 50% of patients reported at least 10 concurrent symptoms, 40% reported having at least 3 moderate-to-severe symptoms, and greater than 25% reported functional interference of symptoms with their ability to work, walk, perform activities, and enjoy life.4 Patients with high-grade glioma (HGG; World Health Organization [WHO] grades III and IV) are particularly vulnerable to declines in physical and neurological function liable to undermine their health-related quality of life (HRQoL), as well as their ability to work and live autonomously, which may place extensive caregiving and economic burdens on family members.5–9 In fact, changes in neuropsychological function including personality paired with the high degree of uncertainty of the time of disease progression may produce significant psychosocial strain commonly reported by families coping with cancer as well as placing patients and their family caregivers at particularly high risk of depression and existential distress.10–16 A systematic review to assess HRQoL in patients diagnosed with meningioma found impaired HRQoL relative to health controls, which persisted years after receiving tumor-directed treatment.17 Those of us who have dedicated our professional lives to caring for neuro-oncology patients fully recognize that there are many unmet needs and concerns of patients and their caregivers further complicated by high symptom burden, often at disease onset, which increases over time due to tumor, treatment effect, or most often, an admixture of both.

Patient-Centered Survivorship Care

This evidence provides strong impetus for us to take clinically meaningful and actionable steps toward broadening the focus of neuro-oncologic care. Survivorship care offers the opportunity to address the unique and multifaceted needs of patients, developed in acknowledgment of the lived, individual experience of a diagnosis of cancer; its treatment and the effects on family members, friends, and caregivers are also impacted by the survivorship experience. While not all those with a diagnosis of or treatment for cancer identify with the term “survivor,” there is wide acceptance of survivorship care’s goal to “raise awareness of the needs of cancer survivors, establish cancer survivorship as a distinct phase of cancer care and to act to ensure the delivery of appropriate survivorship care.”18 Succinctly stated, survivors most need to know how to live with their cancer diagnosis because it is now part of their lives, which do not just return to “normal.”

Survivorship care has become a major topic in oncology and a significant research and health care priority, focused on developing methods and tools to facilitate the provision of survivorship care such as innovating patient-focused survivorship care delivery models, developing and implementing survivorship care plans, and optimizing communication among health care providers, patients, and their families. The need for innovations of survivorship care delivery models is spurred not only by the need to accommodate an ever-growing population of cancer survivors but also by an increasing shortage of oncologists, necessitating an expansion of the health care provider team to include advanced practice nurses, nurse practitioners, and physicians assistants, for example.19,20 Survivorship care–specific education of oncology nurse professionals has also been identified as a significant need in order to address the clinical demand for the requisite expansion of survivorship care delivery. Efforts to provide such education are being undertaken by professional organizations.21 Interprofessional cancer survivorship care provides workforce flexibility to meet the clinical demand irrespective of the care delivery mode itself. The model of survivorship delivery, whether embedded within an active treatment clinic or a separate survivorship clinic, remains best determined locally by the individual cancer treatment center, community based and academic alike, in the absence of any clinical research studies sufficient to inform evidence-based practice regarding the effectiveness or efficacy of either model. Common practical barriers and limitations to these models are capacity, logistics, and billing and coding procedures, as well as adequate education specific to cancer survivorship as ASCO outlined in 2013.19,22 Potential methods to practically address these barriers in the field of neuro-oncology were addressed by Leeper et al.23

The Survivorship Care Plan

The survivorship care plan initiative began in 2006 after the then named Institute of Medicine (IOM) “From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor—Lost in Transition” report recommended the document as a concrete measure toward improving survivorship care.24 Its usage was then accelerated in the United States by the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (CoC) 2012 mandate for cancer patients treated with curative intent to receive survivorship care plans (SCPs). The premise of SCPs is to communicate treatment information and follow-up care recommendations to patients, their families, and other treating physicians, especially primary care providers, given the lack of a universal medical record system. The SCP consists of a treatment summary and a follow-up care plan pertaining to long-term effects of the disease and treatment, monitoring for recurrence and second malignancies, as well as psychosocial issues prevalent among cancer patients as per the recommendations of the IOM “Lost in Transition” report, widely regarded as the guideline for SCP content. The context of survivorship care including the SCP document itself has not been widened into the clinical realm of end-of-life care to date. As such, end-of-life care is not represented within the recommended content for SCPs by either ASCO or the 2006 IOM report, though advanced care planning and directives may be referenced. Health care providers in the various oncologic subspecialties have been investigating what comprises optimal survivorship care planning within their own unique patient populations. Indeed, it is recognized that such specific collaborative, coordinated agendas and efforts require the participation of all stakeholders, including patients and their caregivers, in order to fully develop the care processes of survivorship.25 ASCO has developed a general SCP as well as SCPs specific to several cancers (breast, colorectal, lung, prostate, lymphoma) through a broad consensus process with patient involvement.26 The Children’s Oncology Group created Passport for Care, a web-based support system for clinical decision making, in a compendium with its Long-Term Follow Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers.27 To begin addressing survivorship care needs within the adult neuro-oncology patient population, a neuro-oncology–specific SCP has been developed by a multidisciplinary and interprofessional ad hoc committee and endorsed by the Society for Neuro-Oncology Guidelines Committee.23,28 This neuro-oncology–specific SCP was created using the recommended content for SCPs in the 2006 IOM report and by ASCO to accommodate any WHO diagnosis, grade, and neuro-anatomical location with requisite treatments of our standard armamentarium so as to be as inclusive of as many patients as possible, irrespective of treatment intent. It may be updated over time as necessary and can be used in parts or in its entirety. This SCP is available as open access for download from the Society for Neuro-Oncology’s website under the “Resources” tab for clinical use by any health care professional or health care organization as a medical document.

SCPs are a means to an end; they are not the provision of survivorship care in and of themselves. The SCP is a document whose function is to communicate crucial health care information about an individual patient. The provision of survivorship care lies within the delivery of patient-centered care focused on survivorship needs; the SCP is a vehicle of care coordination and communication aimed at achieving specific goals.29 As has been well documented in the literature, the viability and clinical utility of SCPs to meaningfully impact patient outcomes were not validated prior to the CoC’s implementation and delivery mandate being set forth. Now 12 years since the publication of IOM’s “Lost in Transition” report, there remains scant research evidence of what, if any, progress SCPs have made toward their intended goal of improving survivorship care or improving patient outcomes.30,31 While comprehensive review of the literature and research studies on SCPs to date is beyond the scope of this discussion, much of SCP research has been conducted within breast cancer and gynecologic oncology patient populations. The critiques of these research findings citing the null or negative results of these studies may more accurately reflect poor or inconsistent SCP implementation rather than a lack of effectiveness of the SCP document itself.32

Survivorship Care in Neuro-Oncology

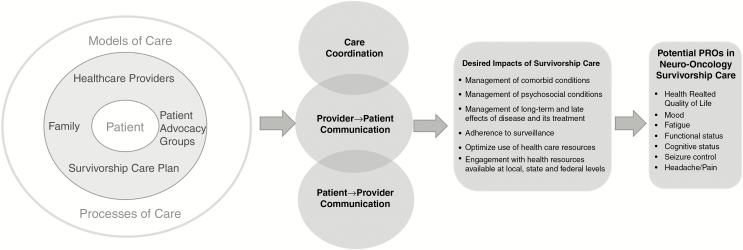

Despite the large knowledge gap regarding SCPs, there is strong interest in continuing to develop and evolve survivorship care. Indeed, ASCO recently endorsed and published a survivorship care guideline for head and neck cancer patients without predication of curative treatment intent.33 Certainly, neuro-oncology patients are no less deserving of survivorship care and it behooves us to be engaged with survivorship care alongside our oncology health care provider colleagues. In fact, the literature suggests that patients and families report unmet needs, as they may experience dissatisfaction with their health care providers, particularly regarding the lack of communication about prognostic uncertainty, disease progression, and education regarding treatment side effects.34–37 Due to the unique needs and issues faced by neuro-oncology patients, evidence from survivorship research conducted within other cancer patient populations may not be as applicable or clinically meaningful to the survivorship experiences of those with neuro-oncologic illnesses. Thus, survivorship care and its research would optimally be conducted with the involvement of all the stakeholders across the international community of neuro-oncology health care providers, patients, and caregivers. Fig. 1 illustrates a possible conceptual framework or model of survivorship care for neuro-oncology patients, including a list of proposed patient-reported outcomes to offer patients for consideration based on patient feedback about signs and symptoms they prioritized as clinical outcome assessments in trials per the definition of the FDA.38 Within the concentric circles, the patient is at the center surrounded by methods and tools by which survivorship care is delivered and facilitated. These provisions are embedded within models of care, or in other words, various ways care is organized among the stakeholders involved in care, including their role expectations and processes of care, reflecting how stakeholders interact and operate within the care system.29 These three layers together depicting patient-centric care focused on issues relevant to survivorship are then fostered and impacted by the 2 constructs to the right of the circles, namely by care coordination, which can be further supported by patient navigation, and crucial conversations initiated by health care providers with patients, their caregivers, family members, and friends to share and discuss their survivorship concerns and needs. The postulated impacts on patient outcomes of survivorship are depicted next, followed by several potential patient-reported outcome measures. The utilization of these specific patient-reported outcome measures is intended to honor the imperative for patients to be directly involved in survivorship care in addition to being the beneficiaries of patient-centric care. This framework is not without limitations, including the use of patient-reported outcome measures derived from a small patient sample in a single country.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework for survivorship care for neuro-oncology patients (PROs: patient-reported outcomes).

To further discuss the importance of the respective patient-reported outcome measures of cognitive status, functional status, and seizure control, patients with CNS tumors may be limited by neurological and cognitive dysfunction and thus have high care and support needs from their social network. For example, patients with a history of seizures may not be able to drive, which further decreases their autonomy.39 Importantly, often even subtle impairments in cognitive functioning such as attention deficits and short-term memory loss may have implications for social and role function and may hinder survivors to return to work.40–42 Moreover, cognitive deficits can hamper communication and decision making and, particularly paired with changes in personality, may present challenges to family relationships.9,43 Cognitive deficits may also be associated with psychological distress, with rates of depression and anxiety up to 48% in patients and up to 40% in caregivers.9,11,15,16,44–46 Most likely due to the complexities of the disease, family caregivers are more vulnerable to clinical levels of distress compared with family members of other types of cancer patients.44 Considering the high symptom burden and need for assistance with activities of daily living, the involvement of family caregivers in survivorship care may be more beneficial compared with other patient populations.

Thus, there is a pressing need to develop efficacious care frameworks that integrate neurocognitive and psychosocial treatments into the clinical practice of neuro-oncology. Patient-centered survivorship care in neuro-oncology may be most effective when, similar to ASCO’s palliative cancer care guidelines, the role of family members in the treatment process is recognized and family caregivers are included in psychosocial supportive care services.47 A family-centric care plan may have implications for patients’ survival, as caregiver function may predict survival in patients with glioblastoma even when controlling for performance status and treatment variables.48 And, unlike most survivorship research focusing on the health and life of a person with a history of cancer beyond the acute diagnosis and treatment phase, we argue that, particularly for those with HGG, delivering patient-centered care (or even ideally family-centered) early in the treatment trajectory may be most effective, as patients may be more cognitively involved in value-based treatment decisions. As suggested by the palliative care literature, patients who were newly diagnosed with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer and randomized to early palliative care integrated with standard oncologic care not only reported significantly improved QoL and mood but also lived longer compared with those who were randomized to standard oncologic care alone.1

As we work toward developing survivorship care for neuro-oncology patients, an interdisciplinary approach that includes evidence-based supportive care strategies will be essential. To this end, systematic research studies specifically engaging neuro-oncology patients and their health care providers in all countries are needed. We believe that research efforts are needed to address two fundamental questions: (i) How do we effectively implement survivorship care in neuro-oncology? and (ii) What supportive care strategies are effective in addressing the unmet needs of neuro-oncology patients and their family caregivers? Regarding the successful implementation of survivorship care and the utility of survivorship care plans in the clinical setting, longitudinal cohort studies could provide information about downstream effects of SCPs on survivors, providers, and health care delivery systems, whereas comparative study designs would be helpful to assess survivorship care planning benefit beyond an institution’s or provider’s usual care. Also, descriptive studies would be valuable of the health care/clinical setting in which a particular institution’s survivorship care planning occurs, who the participants in the process are, and what structures and processes are in place to support quality transitional and follow-up care. Additional descriptive studies would be helpful documenting an organization’s context and its unique factors that promote or inhibit efficacious survivorship care planning—for example, billing and reimbursement. Lastly, observational and experimental studies to evaluate the efficacy and implementation of care planning models and interventions would be ideal. As an example, the vast majority of cancer care across the United States is delivered in community hospital settings. These various studies would provide critical information in developing survivorship care which not only is effective in achieving its goals of improving QoL and illness outcomes, but is culturally specific and locally accessible. We as neuro-oncology health care providers know from our clinical practice that patients receive neuro-oncologic care in both academic and community settings, ultimately returning home where local resources are most likely to be culturally specific and accessible to them as individuals; we will need to think and act locally to effectuate the evolution of survivorship care for those patients who receive care from us, at whatever institution we may work. We can engage with our local oncology colleagues in their survivorship care initiatives or start our own survivorship care initiatives—for example, as a quality improvement project.

Regarding methods and tools targeting unmet survivorship needs of symptom and QoL management, an interdisciplinary strategy integrating pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments including complementary/integrative medicine (CIM) may be a promising approach to patient-centered care. There is a growing body of literature examining non-pharmacological interventions (eg, neurocognitive rehabilitation,49,50 neurorehabilitation,51 in glioma patients52) as well as psychoeducational interventions for family caregivers.53,54 Future research may examine the role of patient–caregiver dyadic interventions in reducing symptoms and improving QoL. Teaching patient–caregiver dyads behavioral coping and relaxation skills together may have the added benefit of enhancing communication regarding symptom management. Additionally, because social support is associated with biological indices (ie, stress hormones and inflammatory cytokines) relevant to patients’ symptom burden and possibly disease progression, a program that not only includes caregivers but also capitalizes on the unique bond of families may be particularly effective in reducing symptoms.55,56 Lastly, according to evidence in the health-behavior literature, dyadic interventions may be not only more efficacious but also more feasible regarding participant retention and treatment adherence compared with patient-only interventions.57–59 Involving a family caregiver to improve compliance may be particularly beneficial for patients affected by memory or cognitive deficits. Lastly, the efficacy of CIM modalities (eg, yoga, meditation, acupuncture) has remained relatively unexplored in patients with CNS tumors, although descriptive studies suggest that between 30% and 65% of neuro-oncologic patients use at least one type of CIM modality.60–62 While the interaction between herbs/supplements and conventional cancer therapy is complex, and translational research is needed before recommendations are appropriate, mind-body medicine such as yoga therapy may be effective in reducing symptom burden and improving QoL. In fact it has been shown to be safe and feasible to enroll patients with HGG while undergoing radiotherapy and their family caregivers in a yoga trial, and larger trials are warranted.63 Research is needed in how to effectively integrate behavioral supportive care strategies into neuro-oncologic care.

In summary, we highlighted the need for patient-centric care in neuro-oncology and methods by which this may be meaningfully actualized within the context of survivorship care, similar to the development of survivorship care in other cancer patient populations, which was also discussed. We also reviewed methods and tools for facilitating the provision of survivorship care with specific attention to survivorship care plans, including the recent development of a neuro-oncologic specific SCP and proposed a conceptual framework for survivorship care in neuro-oncology. Finally, we offered specific recommendations toward developing an evidence base of efficacious survivorship and supportive care interventions.

Funding

No targeted funding to report.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Vimal Patel, PhD, for proofing, formatting, and copyediting the manuscript in preparation for submission.

Conflict of interest statement. No conflicts reported.

Supplement sponsorship. This supplement was funded through an independent medical educational grant from AbbVie.

References

- 1. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. . Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. . Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Donald T. Online tool for reporting symptoms extends survival https://am.asco.org/online-tool-reporting-symptoms-extends-survival. Accessed April 6, 2018.

- 4. Armstrong TS, Vera-Bolanos E, Acquaye AA, Gilbert MR, Ladha H, Mendoza T. The symptom burden of primary brain tumors: evidence for a core set of tumor- and treatment-related symptoms. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(2):252–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Luo Z, Bednarek HL. Employment-contingent health insurance, illness, and labor supply of women: evidence from married women with breast cancer. Health Econ. 2007;16(7):719–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fox SW, Lyon D, Farace E. Symptom clusters in patients with high-grade glioma. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39(1):61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones JM, Cohen SR, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. Quality of life and symptom burden in cancer patients admitted to an acute palliative care unit. J Palliat Care. 2010;26(2):94–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Osoba D, Aaronson NK, Muller M, et al. . Effect of neurological dysfunction on health-related quality of life in patients with high-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 1997;34(3):263–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sterckx W, Coolbrandt A, Dierckx de Casterlé B, et al. . The impact of a high-grade glioma on everyday life: a systematic review from the patient’s and caregiver’s perspective. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(1):107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boele FW, Rooney AG, Grant R, Klein M. Psychiatric symptoms in glioma patients: from diagnosis to management. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1413–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Finocchiaro CY, Petruzzi A, Lamperti E, et al. . The burden of brain tumor: a single-institution study on psychological patterns in caregivers. J Neurooncol. 2012;107(1):175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Litofsky NS, Farace E, Anderson F Jr, Meyers CA, Huang W, Laws ER Jr; Glioma Outcomes Project Investigators Depression in patients with high-grade glioma: results of the Glioma Outcomes Project. Neurosurgery. 2004;54(2):358–366; discussion 366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lucas MR. Psychosocial implications for the patient with a high-grade glioma. J Neurosci Nurs. 2010;42(2):104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pelletier G, Verhoef MJ, Khatri N, Hagen N. Quality of life in brain tumor patients: the relative contributions of depression, fatigue, emotional distress, and existential issues. J Neurooncol. 2002;57(1):41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Petruzzi A, Finocchiaro CY, Lamperti E, Salmaggi A. Living with a brain tumor: reaction profiles in patients and their caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(4):1105–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sherwood PR, Given BA, Given CW, et al. . Predictors of distress in caregivers of persons with a primary malignant brain tumor. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(2):105–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zamanipoor Najafabadi AH, Peeters MCM, Dirven L, et al. . Impaired health-related quality of life in meningioma patients—a systematic review. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(7):897–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nekhlyudov L, Ganz PA, Arora NK, Rowland JH. Going beyond being lost in transition: a decade of progress in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(18):1978–1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rosenzweig MQ, Kota K, van Londen G. Interprofessional management of cancer survivorship: new models of care. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2017;33(4):449–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McCabe M, Boekhout A, Thom B, Corcoran S, Adsuar R, Oeffinger K. Evaluation of nurse practitioner-led survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl):10081 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grant M, McCabe M, Economou D. Nurse education and survivorship: building the specialty through training and program development. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21(4):454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, et al. . American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(5):631–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leeper H, Acquaye A, Bell S, et al. . Survivorship care planning in neuro-oncology. Neurooncol Pract. 2018;5(1):3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Institute of Medicine. In: Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, eds. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2006:9–186. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alfano CM, Smith T, de Moor JS, et al. . An action plan for translating cancer survivorship research into care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(11):dju287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Survivorship Care Planning Tools https://www.asco.org/practice-guidelines/cancer-care-initiatives/prevention-survivorship/survivorship-compendium. Accessed April 6, 2018.

- 27. Poplack DG, Fordis M, Landier W, Bhatia S, Hudson MM, Horowitz ME. Childhood cancer survivor care: development of the Passport for Care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(12):740–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Society for Neuro-Oncology Guidelines Committee. The Neuro-Oncology Patient Survivorship Care Plan https://www.soc-neuro-onc.org/SNO/Resources/Survivorship_Care_Plan.aspx. Accessed April 6, 2018.

- 29. Parry C, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Can’t see the forest for the care plan: a call to revisit the context of care planning. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(21):2651–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mayer DK, Birken SA, Check DK, Chen RC. Summing it up: an integrative review of studies of cancer survivorship care plans (2006-2013). Cancer. 2015;121(7):978–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Birken SA, Ellis SD, Walker JS, et al. . Guidelines for the use of survivorship care plans: a systematic quality appraisal using the AGREE II instrument. Implement Sci. 2015;10:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mayer DK, Birken SA, Chen RC. Avoiding implementation errors in cancer survivorship care plan effectiveness studies. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(31):3528–3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nekhlyudov L, Lacchetti C, Siu LL. Head and neck cancer survivorship care guideline: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline endorsement summary. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(3):167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ford E, Catt S, Chalmers A, Fallowfield L. Systematic review of supportive care needs in patients with primary malignant brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(4):392–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Halkett GK, Lobb EA, Oldham L, Nowak AK. The information and support needs of patients diagnosed with high grade Glioma. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(1):112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Halkett GK, Jiwa M, Lobb EA. Patients’ perspectives on the role of their general practitioner after receiving an advanced cancer diagnosis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2015;24(5):662–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lageman SK, Brown PD, Anderson SK, et al. . Exploring primary brain tumor patient and caregiver needs and preferences in brief educational and support opportunities. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(3):851–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Armstrong TS, Bishof AM, Brown PD, Klein M, Taphoorn MJ, Theodore-Oklota C. Determining priority signs and symptoms for use as clinical outcomes assessments in trials including patients with malignant gliomas: Panel 1 Report. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(Suppl 2):ii1–ii12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Klein M, Taphoorn MJ, Heimans JJ, et al. . Neurobehavioral status and health-related quality of life in newly diagnosed high-grade glioma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(20):4037–4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hickmann AK, Hechtner M, Nadji-Ohl M, et al. . Evaluating patients for psychosocial distress and supportive care needs based on health-related quality of life in primary brain tumors: a prospective multicenter analysis of patients with gliomas in an outpatient setting. J Neurooncol. 2017;131(1):135–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nugent BD, Weimer J, Choi CJ, et al. . Work productivity and neuropsychological function in persons with skull base tumors. Neurooncol Pract. 2014;1(3):106–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Osoba D, Aaronson NK, Muller M, et al. . Effect of neurological dysfunction on health-related quality of life in patients with high-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 1997;34(3):263–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ford E, Catt S, Chalmers A, Fallowfield L. Systematic review of supportive care needs in patients with primary malignant brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(4):392–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Boele FW, Heimans JJ, Aaronson NK, et al. . Health-related quality of life of significant others of patients with malignant CNS versus non-CNS tumors: a comparative study. J Neurooncol. 2013;115(1):87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sherwood PR, Donovan HS, Given CW, et al. . Predictors of employment and lost hours from work in cancer caregivers. Psychooncology. 2008;17(6):598–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sherwood PR, Given BA, Donovan H, et al. . Guiding research in family care: a new approach to oncology caregiving. Psychooncology. 2008;17(10):986–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. . Palliative cancer care a decade later: accomplishments, the need, next steps—from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(18):3052–3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boele FW, Given CW, Given BA, et al. . Family caregivers’ level of mastery predicts survival of patients with glioblastoma: a preliminary report. Cancer. 2017;123(5):832–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gehring K, Sitskoorn MM, Gundy CM, et al. . Cognitive rehabilitation in patients with gliomas: a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3712–3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hassler MR, Elandt K, Preusser M, et al. . Neurocognitive training in patients with high-grade glioma: a pilot study. J Neurooncol. 2010;97(1):109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bartolo M, Zucchella C, Pace A, et al. . Early rehabilitation after surgery improves functional outcome in inpatients with brain tumours. J Neurooncol. 2012;107(3):537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Piil K, Juhler M, Jakobsen J, Jarden M. Controlled rehabilitative and supportive care intervention trials in patients with high-grade gliomas and their caregivers: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2016;6(1):27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Boele FW, Hoeben W, Hilverda K, et al. . Enhancing quality of life and mastery of informal caregivers of high-grade glioma patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Neurooncol. 2013;111(3):303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sherwood PR, Given BA, Given CW, Sikorskii A, You M, Prince J. The impact of a problem-solving intervention on increasing caregiver assistance and improving caregiver health. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(9):1937–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Antoni MH, Lutgendorf SK, Cole SW, et al. . The influence of bio-behavioural factors on tumour biology: pathways and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(3):240–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK, Antoni MH. Host factors and cancer progression: biobehavioral signaling pathways and interventions. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(26):4094–4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Martire LM, Schulz R, Keefe FJ, et al. . Feasibility of a dyadic intervention for management of osteoarthritis: a pilot study with older patients and their spousal caregivers. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7(1):53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Felgoise SH, McClure KS, Houts PS. Project Genesis: assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(6):1036–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wallace JP, Raglin JS, Jastremski CA. Twelve month adherence of adults who joined a fitness program with a spouse vs without a spouse. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1995;35(3):206–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Armstrong T, Cohen MZ, Hess KR, et al. . Complementary and alternative medicine use and quality of life in patients with primary brain tumors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32(2):148–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Armstrong TS, Gilbert MR. Use of complementary and alternative medical therapy by patients with primary brain tumors. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8(3):264–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fox S, Laws ER Jr, Anderson F Jr, Farace E. Complementary therapy use and quality of life in persons with high-grade gliomas. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006;38(4):212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Milbury K, Mallaiah S, Mahajan A, et al. . Yoga program for high-grade glioma patients undergoing radiotherapy and their family caregivers. Integr Cancer Ther. 2017;1:1534735417689882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]