Abstract

Multinucleated giant cell (MGC) reaction in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) usually represents a stromal foreign body reaction to keratin from neoplastic epithelial cells. We describe and illustrate by double immunohistochemistry a case of a tongue squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in a 70-year-old female patient, with a copious MGC reaction not associated to keratin, showing a histopathological pattern not described before. The MGCs were directly associated with neoplastic cells, which are phagocytosed by the MGCs. Immunohistochemistry for CD68, AE1/AE3, CD163, CD11c, RANK, RANK-L, OPG were performed, as well as double staining for CD68 and AE1/AE3 to better illustrate the relationship between MGCs and neoplastic cells. The clinical and biological significance of this pattern of MGC reaction in OSCC needs to be better elucidated.

Keywords: Oral squamous cell carcinoma, Multinucleated giant cells, Immunohistochemistry, Phagocytosis

Introduction

Interactions between tumoral and stromal cells are important events in cancer, and inflammation is an important reaction that can be associated with better or worse prognosis of neoplasms, depending on the type of inflammation and of the malignancy. Macrophages are an important component of the cancer-associated inflammation in several types of cancer, including oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) [1–3].

There are two different cell populations in macrophages given by a mechanism called macrophage polarization by which, in response to microenvironmental signals, the macrophage expresses different functional programs, acquiring a specific phenotype such as M1 or M2. M1 macrophages (classically activated macrophages), produce pro-inflammatory cytokines: interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-12, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFa), these M1 macrophages can present a antitumoral response in cancer; while M2 macrophages (alternatively activated macrophages), may have a pro-tumoral response, by releasing IL-4, IL-10 cytokines and transforming growth factor (TGF)-b promoting tumoral growth, angiogenesis, extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, and even metastasis [4–7]. Macrophages fusion resulting into multinucleated giant cells (MGC) has been described as a host response to the tumoral cells in several types of carcinomas, however, the prognostic implications are not clear [8–13].

To the best of our knowledge, few cases of OSCC and lip squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) presenting MGCs have been reported, usually representing a foreign body reaction to keratin. In this study we describe and illustrate a case of tongue SCC with an unusual profuse reaction of MGC surrounding and phagocytosing neoplastic cells, but without association with extracellular keratin.

Case Report

A 70 year-old Guatemalan female presented with an ulcerated mass on the lateral border of the tongue, with an approximate duration of 4 months. An incisional biopsy was performed and the specimen was sent to the pathology service at Centro Clínico de Cabeza y Cuello, for histopathological analysis.

The gross specimen consisted of two fragments of soft tissue with firm-elastic consistency and brownish color. The diagnosis was invasive SCC, moderately differentiated. The superficial mucosa was covered by dysplastic stratified squamous epithelium from which originated the neoplastic proliferation, composed of sheets and islands of pleomorphic and hyperchromatic squamous epithelial cells that infiltrated deeply the subjacent connective and muscular tissues, in a background of peritumoral and intratumoral inflammatory cells. A striking and exuberant macrophagic and MGC reaction involving and infiltrating the tumoral nests, in absence of keratin pearls or extracellular keratin filaments was evident (Fig. 1a). Peritumoral mononuclear macrophages predominated in the superficial areas adjacent to surface epithelium, while the MGC were directly associated to tumoral nests mainly in deeper areas of the tumor, adjacent to skeletal muscle fibers.

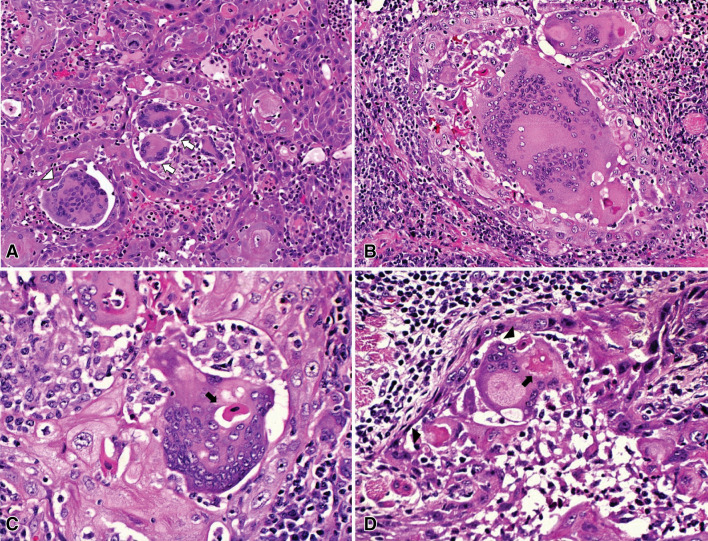

Fig. 1.

Histopathological aspects of intense multinucleated giant cell reaction in a tongue squamous cell carcinoma. a Inflammatory response associated to the neoplastic cells consisting in an exuberant macrophagic and MGC reaction infiltrating tumoral nests, in absence of keratin pearls and surrounded by a background of a prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. In this field are observed foreign-body type MGCs with random arrangement of nuclei (white arrowhead), and also Langhans type MGCs with a horseshoe pattern of nuclei at the periphery of the cytoplasm (white arrows) (HE 200×). b A foreign-body type MGC presenting more than 200 nuclei (HE 200×). c Epithelial cells fagocitated in the cytoplasm of MGC (arrows) (HE 400×). d MGCs engulfing an eosinophilic corpuscle that could be an epithelial cell in degeneration, the cytoplasm of MGC shows a modified shape that resembles pseudopods or a phagocytic vacuole (arrowhead), also a fagocitated cell is present within the cytoplasm of the MGC (arrow) (HE 400×)

The predominant MGCs were of foreign-body type, however, also Langhans type cells were found. Most of the foreign-body type MGCs presented more than 40 nuclei, some exceeding 200 (Fig. 1b).

MGC showed cytoplasmic eosinophilic figures, some of them with a basophilic center, suggesting degenerating epithelial cells, phagocytosed by the MGCs, and in some areas, the MGCs seemed to be engulfing the neoplastic cells (Fig. 1c, d).

Immunohistochemical (IHC) reactions including double staining for CD68 and AE1/AE3 were performed to illustrate the relationship between MGCs and neoplastic cells. Additionally, to establish the polarization of M1/M2 macrophages, IHC reactions for CD163 and CD11c were also done. To determine the possible pathway of MGCs formation, IHC for RANK, RANK-L and OPG was also performed.

The IHC was performed in sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues that were dewaxed with xylene and then hydrated in an ethanol series. Antigen retrieval was performed by immersing the sections for 3 min in citrate buffer solution (pH 6.0) in a pressure cooker for CK-cocktail, CD68 and, CD163 reactions, and in a microwave oven for 24 min for RANK, RANKL, OPG and CD11c. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 10% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min. Subsequently, preparations were washed in phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.4) and incubated overnight with the primary antibodies (Table 1). Slides were exposed to avidin–biotin complex and horseradish peroxidase reagents: LSAB Kit; Dako Cytomation, for CK-cocktail, CD68 and, CD163 reactions and Vectastain ABC Kit–Rabbit, Vector, for RANK, RANKL, OPG and CD11c. The reaction was finally revealed with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), and the tissue sections were counterstained with Carazzi hematoxylin. The positive controls for each marker are cited in Table 1 and the negative controls were obtained by omitting the specific primary antibody. Information about IHC is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical reactions

| Antibody | Source/clone | Dilution | Positive control | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD68 | Dako, PG-M1 | 1:400 | Mucocele (macrophages) | Positive in MM and MGC |

| CK-cocktail | Dako, AE1/AE3 | 1:500 | OSCC | Strongly positive in tumoral cells |

| CD163 | Novocastra, 10D6 | 1:4000 | Mucocele (macrophages) | Negative in MGC and positive in MM surrounding the tumor |

| CD11c | Abcam, N418 | 1:100 | Bone marrow | Positive in MGC and in intratumoral MM |

| RANK | Abcam, polyclonal | 1:300 | T-cell lymphoma | Positive in half of the MGC and most of the intratumoral MM |

| RANKL | Abcam, 64C1385 | 1:500 | Lymph node | Positive in MGC and peritumoral inflammatory infiltrate |

| OPG | Abcam, polyclonal | 1:200 | Osteoblasts | Negative in tumoral and stromal components |

OSCC oral squamous cell carcinoma, MM mononuclear macrophages, MGC multinucleated giant cells

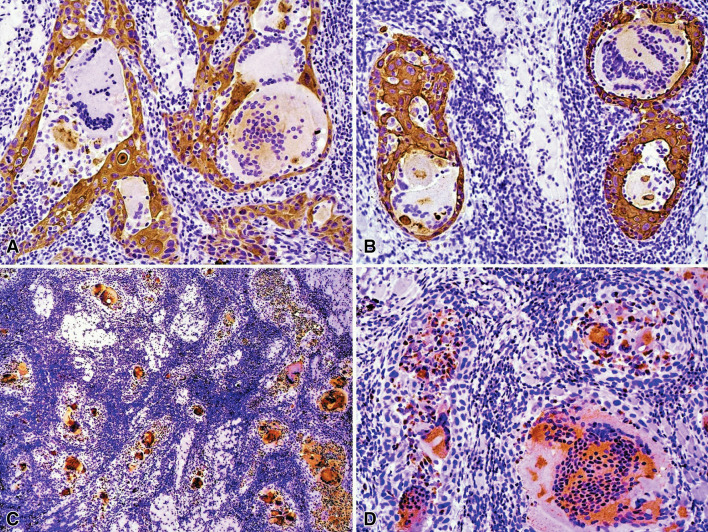

Surface epithelium and islands of OSCC stained with AE1/AE3. MGCs located in the deeper stroma, contained in the cytoplasm AE1/AE3-positive figures suggestive of phagocytosed epithelial cells (Fig. 2 A, B). Most of the infiltrating mononuclear inflammatory cells and all MGCs were positive for CD68 (Fig. 2c, d). Tumor cells adjacent to the surface epithelium were surrounded by a strong reaction of peritumoral CD68-positive mononuclear macrophages and few CD68-positive MGCs were also observed on this area.

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical features of intense multinucleated giant cell reaction in a tongue squamous cell carcinoma. a, b Immunohistochemistry for AE1/AE3. Positive neoplastic cell islands were infiltrated by mononuclear cells compatible with macrophages and lymphocytes, and centrally by MGC of variable sizes, some of them containing AE1/AE3-positive figures in the cytoplasm (immunoperoxidase, 200×). c, d Many tumor infiltrating mononuclear and MGCs were positive for CD68. (immunoperoxidase, c 50× and d 200×)

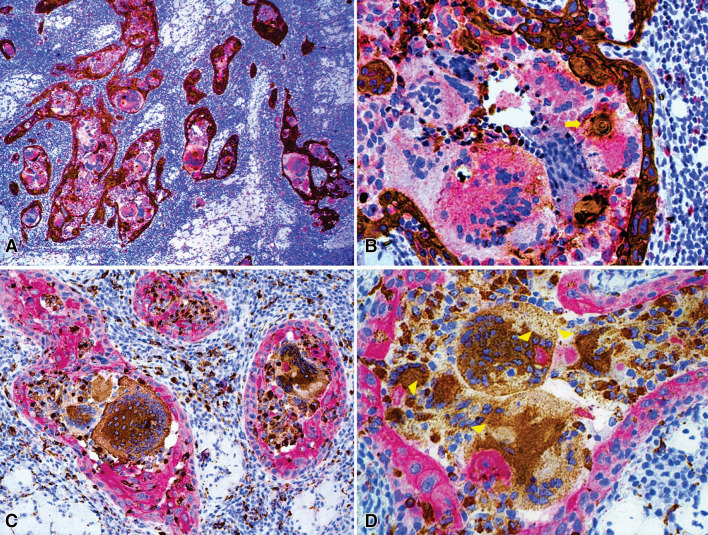

In order to better illustrate the relationship between MGCs and the neoplastic cells, IHC double staining was performed using AE1/AE3 and CD68 antibodies in the same tissue section, with the EnVision G|2 Doublestain System, Rabbit/Mouse (DAB+/Permanent Red) (Dako/Agilent Santa Clara, CA). In the first double IHC, DAB and Permanent Red was used as chromogen for AE1/AE3 and CD68 respectively, illustrating the intense macrophagic and MGC infiltration surrounding the tumoral islands (Fig. 3a, b). Large MGCs were found at the center of the tumor islands, while smaller ones resembling Langhans-type were located peritumorally. In the second double IHC, the chromogens were inverted, for CD68 was used DAB as chromogen and for AE1/AE3 Permanent Red, confirming the same pattern between OSCC and MGCs (Fig. 3c, d). In both double IHC, we observed figures suggestive of phagocytosis of neoplastic cells by MGCs (Fig. 3b, d).

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical double staining for AE1/AE3 and CD68. a In low power magnification, an intense macrophagic and MGC infiltration was observed in all the tumoral islands, while scarce positivity for CD68 was observed within the lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the stroma. b Area of phagocytosis of the neoplastic cells by MGC (yellow arrow). (AE1/AE3 immunoperoxidase and CD68 permanent red, a 100×, b 400×). c Infiltrating intratumoral macrophages and MGCs, as well as peritumoral and stromal macrophages admixed to a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate of the stroma. d Areas of phagocytosis of the neoplastic cells by MGCs (yellow arrowheads). (CD68 immunoperoxidase and AE1/AE3 permanent red, c 200×, d 400×)

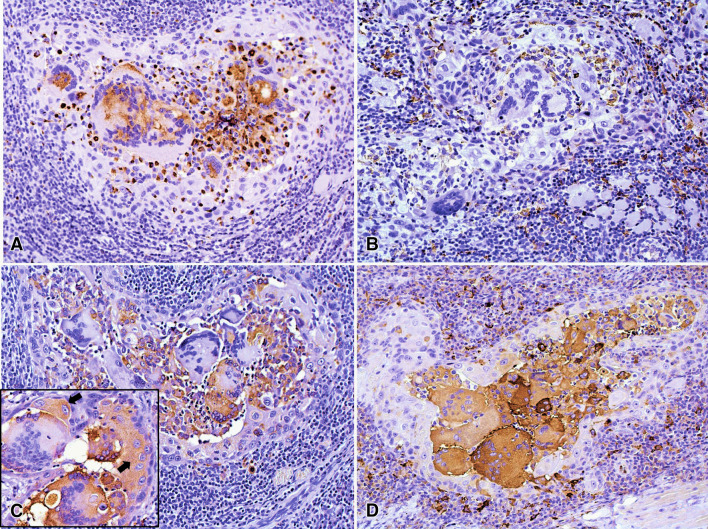

Most MGCs were positive for CD11-c and negative for CD163, the first was also expressed by the intratumoral mononuclear macrophages adjacent to MGCs, while CD163 was positive in the macrophages surrounding the tumor (Fig. 4a, b). Tumoral and stromal components were negative for OPG. Approximately half of the MGCs and most of the intratumoral mononuclear macrophages were positive for RANK, while the macrophages surrounding the tumor were negative. In focal areas neoplastic cells showed weak positivity for RANK. All MGCs were strongly positive for RANK-L, as well as the inflammatory cells surrounding the tumor nests (Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 4.

Immunoexpression of CD11-c, CD163, RANK and RANKL. a Most of MGCs were positive for CD11-c, which also was expressed by the intratumoral mononuclear macrophages adjacent to MGCs. b The MGCs were negative for CD163 that was positive in the macrophages surrounding the tumoral cells. c Approximately half of the MGCs were positive for RANK, also most of the intratumoral macrophages showed positivity, while the macrophages surrounding the tumor were negative. Also, focal areas of tumor showed weak positivity for RANK (arrows in inset). d All the MGCs were strongly positive for RANKL, as well as several mononuclear inflammatory cells. (immunoperoxidase, 200×, inset: 400×)

Discussion

Cancer progression is influenced by the microenvironment conditions given by interactions between parenchymal and stromal cells. Diverse stromal reactions as fibrosis, cancer associated fibroblasts/myofibroblasts, inflammation, immune response and angiogenesis have been associated with prognosis in several types of cancer. Lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells represent the main inflammatory and immune response which can play dual roles during tumorigenesis [1, 3]. Macrophages can be abundant in oral squamous cell carcinoma and other malignancies, and according to the polarization (M1 vs. M2) are associated with a dual tumor interaction: antitumoral (M1, induced by Th1 cytokines) or pro-tumoral response (M2, induced by Th2 cytokines) [4, 6, 7]. High infiltration of M2 polarized macrophages is associated with poor tumor outcome, and progression in OSSC [14, 15].

Th1 cytokines such as interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha as well as Th2 cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-13, can induce macrophage fusion, resulting into MGCs which has been described as a host response to the tumoral cells in several types of carcinomas; however, it is uncertain if the presence of MGC have prognostic implications [9, 10, 12, 13].

Cases of OSCC and lip SCC rich in MGCs have been reported in few studies, usually as a foreign body reaction to extracellular keratin. To date, presence/distribution of MGCs has not been associated with any clinical parameters [8, 11, 12, 16].

Brandwein-Gensler et al. in 2005 evaluated 292 cases of oral SCC from which 77% presented foreign body reaction to keratin, while Santos et al. reported the frequency of about 40% of MGCs in lip SCC in a series of 91 cases, showing a correlation between MGC reaction and keratinization of the tumor. In short, in these two reports and others of lip and intraoral SCC, the presence of MGCs represented a foreign body reaction to keratin [8, 11, 16]. One exception was the report of Emanuel et al., of a cutaneous lower lip SCC, describing the presence of MGCs as an osteoclastic giant-cell-like proliferation, not related to keratin [18]. The present case shows a rather unique histopathological pattern, considering morphology, size and high number of MGCs surrounding and phagocytizing tumoral cells.

We observed a profuse reaction of mononuclear macrophages and MGCs practically in the totality of the tumor sheets and islands, with MGCs more frequent and larger in the deeper areas of the connective tissue. In addition, the MGCs were unusually large, most showing more than 40 nuclei, and some exceeding 100 or 200 nuclei, some displaying in the cytoplasm phagocytosed neoplastic cells without apparent keratinization or apoptosis.

All MGCs were positive for CD68, confirming its macrophagic origin. We also observed that most mononuclear macrophages were positive for CD163 while the majority of MGCs were negative, conversely MGCs showed predominant positivity for the M1 marker CD11-c, in accordance to the most common immunophenotype of MGCs present in labial and intra-oral OSCC as previously described in the literature [12, 17, 18].

In some cancer types, activated or M1 macrophages present in the tumor, are considered to play a crucial role in preventing progression as they are potent effector cells capable of killing tumor cells by direct and indirect effects, and they also can activate and recruit cytotoxic T cells via antigen presentation. On the other hand, M2 macrophages have been associated with tumor growth and metastasis by enzymatic matrix degradation, production of immunosuppressive cytokines/chemokines and angiogenic factors [4, 19, 20]. Thus, according to previous reports, the present case also showed a predominant M1 phenotype suggesting that the MGC reaction could play an antitumor activity in labial SCC and OSCC.

Interactions between receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK) and its ligand (RANKL) are required for osteoclastogenesis, with osteoprotegerin (OPG) acting as an inhibitor. These molecules have been studied mainly in osteoclasts [20–22]. Khan et al. observed by Western blot, that foreign body MGCs were negative for osteoclast specific markers (RANK, NFATc1, CTSK); and in this context, our immunohistochemistry results indicate that the giant cells in the present case have an osteoclast-like phenotype [23].

Up-regulation of RANK and secretion of RANKL by OSCC cells and high expression of these markers in associated multinucleated osteoclasts, have been described previously [24, 25]. In the present case, focal areas of OSCC weakly expressed RANK, that was strongly positive in mononuclear intratumoral macrophages and about half of MGCs; RANKL was positive in all MGCs, as well as in a significant proportion of stromal and inflammatory cell components, leading us to consider that the MGC reaction was induced mainly by stromal cells instead of the tumor itself, and that the MGC differentiation was likely produced by the RANK/RANKL pathway.

In conclusion we described an unusual MGC reaction not associated to extracellular keratin in a SCC of the tongue. The giant cells seemed to be formed by the RANK/RANKL pathway, and they surrounded and phagocytosed neoplastic cells. The biological and clinical significance of this type of MGCs reaction in OSCC are unknown and future studies are required to better understand this phenomenon.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All of authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest and no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.De Wever O, Mareel M. Role of tissue stroma in cancer cell invasion. J Pathol. 2003;200(4):429–447. doi: 10.1002/path.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Visser KE, Coussens LM. The inflammatory tumor microenvironment and its impact on cancer development. Contrib Microbiol. 2006;13:118–137. doi: 10.1159/000092969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Essa AA, Yamazaki M, Maruyama S, Abé T, Babkair H, Raghib AM, et al. Tumour-associated macrophages are recruited and differentiated in the neoplastic stroma of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Pathology. 2016;48(3):219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma J, Liu L, Che G, Yu N, Dai F, You Z. The M1 form of tumor-associated macrophages in non-small cell lung cancer is positively associated with survival time. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laoui D, Movahedi K, Van Overmeire E, Van den Bossche J, Schouppe E, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages in breast cancer: distinct subsets, distinct functions. Int J Dev Biol. 2011;55(7–9):861–867. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.113371dl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falleni M, Savi F, Tosi D, Agape E, Cerri A, Moneghini L, et al. M1 and M2 macrophages’ clinicopathological significance in cutaneous melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2017;27(3):200–210. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu JM, Liu K, Liu JH, Jiang XL, Wang XL, Chen YZ, et al. CD163 as a marker of M2 macrophage, contribute to predicte aggressiveness and prognosis of Kazakh esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(13):21526–21538. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burkhardt A, Höltje WJ. The effects of intra-arterial bleomycin therapy on squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Biopsy and autopsy examinations. J Maxillofac Surg. 1975;3(4):217–230. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0503(75)80048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helming L, Gordon S. The molecular basis of macrophage fusion. Immunobiology. 2007;212(9–10):785–793. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks E, Simmons-Arnold L, Naud S, Evans MF, Elhosseiny A. Multinucleated giant cells’ incidence, immune markers, and significance: a study of 172 cases of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3:95–99. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0110-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patil S, Rao RS, Ganavi BS. A foreigner in squamous cell carcinoma! J Int Oral Health. 2013;5(5):147–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santos HB, Miguel MC, Pinto LP, Gordón-Núñez MA, Alves PM, Nonaka CF. Multinucleated giant cell reaction in lower lip squamous cell carcinoma: a clinical, morphological, and immunohistochemical study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46:773–779. doi: 10.1111/jop.12565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid MD, Muraki T, HooKim K, Memis B, Graham RP, Allende D, et al. Cytologic features and clinical implications of undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclastic giant cells of the pancreas: an analysis of 15 cases. Cancer. 2017;125:563–575. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber M, Iliopoulos C, Moebius P, Büttner-Herold M, Amann K, Ries J, Preidl R, et al. Prognostic significance of macrophage polarization in early stage oral squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2016;52:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petruzzi MN, Cherubini K, Salum FG, de Figueiredo MA. Role of tumour-associated macrophages in oral squamous cells carcinoma progression: an update on current knowledge. Diagn Pathol. 2017;12(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s13000-017-0623-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandwein-Gensler M, Teixeira MS, Lewis CM, Lee B, Rolnitzky L, Hille JJ, et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: histologic risk assessment, but not margin status, is strongly predictive of local disease-free and overall survival. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(2):167–178. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000149687.90710.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essa AA, Yamazaki M, Maruyama S, Abé T, Babkair H, Cheng J, et al. Keratin pearl degradation in oral squamous cell carcinoma: reciprocal roles of neutrophils and macrophages. J Oral Pathol Med. 2014;43(10):778–784. doi: 10.1111/jop.12197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emanuel PO, Shim H, Phelps RG. Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with osteoclastic giant-cell-like proliferation. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:930–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sica A, Larghi P, Mancino A, Rubino L, Porta C, Totaro MG, et al. Macrophage polarization in tumour progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18(5):349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Won KY, Kalil RK, Kim YW, Park YK. RANK signalling in bone lesions with osteoclast-like giant cells. Pathology. 2011;43(4):318–321. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e3283463536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor RM, Kashima TG, Hemingway FK, Dongre A, Knowles HJ, Athanasou NA. CD14- mononuclear stromal cells support (CD14+) monocyte-osteoclast differentiation in aneurysmal bone cyst. Lab Invest. 2012;92(4):600–605. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Branstetter D, Rohrbach K, Huang LY, Soriano R, Tometsko M, Blake M, et al. RANK and RANK ligand expression in primary human osteosarcoma. J Bone Oncol. 2015;4(3):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan UA, Hashimi SM, Khan S, Quan J, Bakr MM, Forwood MR, et al. Differential expression of chemokines, chemokine receptors and proteinases by foreign body giant cells (FBGCs) and osteoclasts. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115(7):1290–1298. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chuang FH, Hsue SS, Wu CW, Chen YK. Immunohistochemical expression of RANKL, RANK, and OPG in human oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38(10):753–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Junior CR, Liu M, Li F, D’Silva NJ, Kirkwood KL. Oral squamous carcinoma cells secrete RANKL directly supporting osteolytic bone loss. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(2):119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]