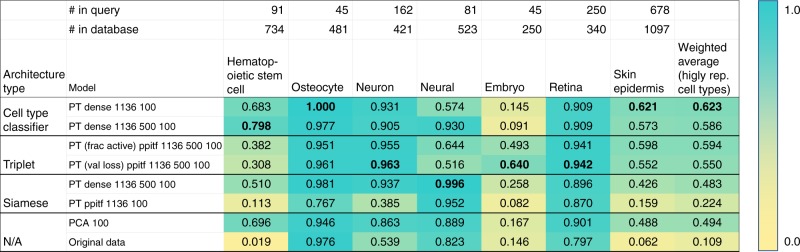

Fig. 3.

Neural embedding retrieval testing results. Retrieval testing results of various architectures, as well as PCA and the original (unreduced) expression data. Scores are MAFP (mean average flexible precision) values (Supporting Methods). “PT” indicates that the model had been pretrained using the unsupervised strategy (Supporting Methods). “Ppitf” refers to architectures based on protein–protien and protein–DNA interactions (Supporting Methods, Supplementary Fig. 12). Numbers after the model name indicate the hidden layer sizes. For example, “dense 1136 500 100” is an architecture with three hidden layers. The metrics in parenthesis for the triplet architectures indicate the metric used to select the best weights over the training epochs. For example, “frac active” indicates that the weights chosen for that model were the ones that had the lowest fraction of active triplets in each mini-batch. We highlight the best performing model in each cell type with a bolded value. We can see that in every column, the best model is always one of our neural embedding models. The final column shows the weighted average score over those cell types, where the weights are the number of such cells in the query set. The best neural embedding model (PT dense 1136 100, top row) outperformed PCA 100 (0.623 vs. 0.494) with a p-value of 1.253 × 10−41 based on two-tailed t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file