Abstract

The regulation of crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) pathway has recently become a topic of intensive research and has been explored in terms of several aspects, including phylogenetics, genomics, and transcriptomics. Orchidaceae, which contains approximately 9,000 CAM species, is one of the largest lineages using this special photosynthetic pathway. However, no comprehensive transcriptomic profiling focused on CAM regulation in orchid species had previously been performed. In this report, we present two Illumina RNA-seq datasets, including a total of 24 mature leaf samples with 844.4 million reads, from Dendrobium catenatum (Orchidaceae), a facultative CAM species. The first dataset was generated from a time-course experiment based on the typical CAM phases in a diel. The second was derived from an experiment on drought stress and stress removal. A series of quality assessments were conducted to verify the reliability of the datasets. These transcriptomic profiling datasets will be useful to explore and understand the essence of CAM regulation.

Subject terms: Plant physiology, Transcriptomics, Drought, RNA sequencing

Background & Summary

Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) is the most important photosynthetic physiology by which plants adapt to seasonal water-limiting areas. A CAM plant can assimilate CO2 into the opening stoma during the night and employ it in the Calvin cycle under stoma closure during the following day. This physiological process reduces evaporative demand by performing stomatal opening during the cooler nighttime instead of during the daytime when the transpiration rate would be higher. Hence, plants engaged in CAM have higher water use efficiency than their C3 and C4 counterparts1 and are considered to be important contributors to agriculture in semiarid and arid regions2–4.

Although the core CAM pathway has been delineated in detail5, the regulatory mechanisms of these and other associated processes, including stomatal movement, carbohydrate metabolism, and transmembrane transport under circadian rhythms, remain largely unknown. The bulk of recent studies in this field have mainly relied on gene phylogenetic analyses6–8, genomics9–11, proteomics12,13, and transcriptomics13–19. These published transcriptomic data include species from the genera Anans (Bromeliaceae), Agave (Agavaceae), Kalanchoë (Crassulaceae), Mesembryanthemum (Aizoaceae) and Talinum (Portulacaceae) but no taxa from Orchidaceae. The orchid family, the second largest angiospermous group, including approximately 25,000 species, is a significant lineage of CAM species because approximately 9,000 of its members are estimated to utilize this special pathway20. Hence, comprehensive transcriptomic profiling of orchid CAM species should be performed.

Recently, two CAM genomes from orchid species, Phalaenopsis equetris and Dendrobium catenatum (=D. officinale), have been published9,21,22, laying a foundation for CAM research. P. equetris is an obligate CAM plant9 with low metabolic plasticity to environmental changes23. However, D. catenaum is a facultative CAM plant24 that can adjust the intensity of the CAM pathway in response to external stresses, such as drought25, which allows researchers to compare varied gradients of physiological activities through manipulating experimental conditions26. Consequently, the latter orchid should be considered a better candidate for CAM studies than the former. To date, several RNA-seq datasets for D. catenatum have been constructed to examine gene expression in chilling stress27, alkaloid biosynthesis28, polysaccharides synthesis29,30, seed development31, and organ-specific regulation32 but not in CAM processes.

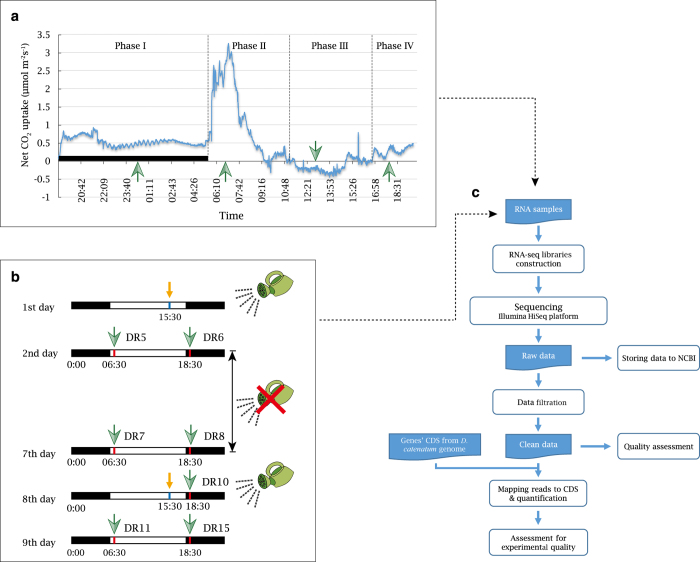

In this study, we conducted two experiments on D. catenatum to generate two RNA-seq datasets. The first experiment aimed to collect the gene expression profile (Dataset I) for CAM and the operation of associated pathways in a diel with four typical phases (Fig. 1a); the second aimed to record the gene expression profile (Dataset II) during the alternation of day and night under drought stress and upon stress removal (Fig. 1b). These experiments yielded 24 samples with a total of 844.4 million reads of transcriptome data from mature leaves (Data Citation 1). Additionally, quality assessments of the data were conducted to verify their reliability (Fig. 1c). We believe that these profiles will help to deepen the comprehensive understanding of the essence of CAM regulation.

Figure 1. Overview of the experimental design and analysis pipeline.

(a) The sampling scheme based on typical CAM phases according to the CO2 exchange rate during a natural day-night cycle. (b) The sampling scheme under sustained drought stress and stress removal. (c) Flow chart of the D. catenatum RNA-seq experiments and data analyses. Green arrows indicate sample collection times, and yellow arrows indicate watering times. Black bars indicate dark periods.

Methods

Design and sample collection of experiment I

Clones of D. catenatum were cultivated in white and transparent pots (5.0 cm in diameter) with sphagnum moss as the matrix. The plants were grown in a greenhouse with temperatures from 22 to 28 °C and relative humidity from 40 to 60%. The experiments were initiated with strong eight-month-old individuals (clones; 12–14 cm height) grown in matrix maintained at approximately 30% volumetric water content, which ensured that these plants did not undergo drought or waterlogging.

During the period when leaf samples were collected, we measured the net CO2 exchange rates by Li-6400XT (Li-COR Biosciences Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) to confirm the four CAM phases5 of the plants in a diel. The following parameters were set for the equipment with a double-sided transparent leaf cuvette: photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD), natural light; cuvette temperature inside, synced with the outside; CO2 concentration, atmosphere; flow rate, 200 μmol s−1; and cuvette fan speed, fast. According to the curve of CO2 exchange rates, leaf samples were collected at 00:30, 06:30, 13:00 and 17:30 (Fig. 1a), which represented Phases I, II, III and IV, respectively. The third and fourth mature leaves from the apex of each individual were harvested and combined as one sample. Three biological replicates were collected for Phase I, five for Phase II, three for Phase III and six for Phase IV. These excised leaves were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Design and sample collection of experiment II

Tissue-cultured D. catenatum plants from seeds were grown in plastic pots (8.0 cm in diameter) filled with a substrate mix of composted pine bark and small stones. The plants were kept in a growth chamber with a temperature of 28/22 °C (day/night), a photoperiod of 12/12 hr (day/night), a light intensity of ~100 μmol m−2s−1, a relative humidity of 50/70% (day/night), and watering every two days at 15:30. Vigorous eight-month-old plants with a height of ~12 cm were chosen for the follow-up experiment. Irrigation was performed on the first day, omitted from the second to the seventh day, and recommenced on the eighth day. (Fig. 1b). The mature fourth leaf from the apex of each individual was harvested at both 06:30 and 18:30 (half an hour after light on and off, respectively) on the second, seventh, and ninth days and at 18:30 on the eighth day (Fig. 1b). Each sample time point included only one biological replicate. These samples were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

RNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from ground tissue using an SDS (prosodium dodecylsulfate) protocol proposed by Cen et al.33. DNA contamination was removed with recombinant DNase I (Takara Bio, http://www.takarabiomed.com.cn/). When the RNA quality tallied with the standards (see Technical Validation section), RNA-seq libraries were constructed using the TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, http://www.illumina.com/). The libraries from experiment I were sequenced in the 150 nt paired-end mode on an Illumina HiSeq2500 platform at Annoroad Gene Technology (Beijing, China; http://www.annoroad.com), and the other libraries were sequenced in the 90 nt paired-end mode on an Illumina Hiseq2000 platform at the Beijing Genomics Institute (Shenzhen, China; http://www.genomics.cn).

Data filtering and gene quantification

The raw RNA-seq reads were cleaned using the Fastq_clean procedure by Zhang et al.34, which included trimming adapters and low-quality bases and removing rRNA and viral sequences. The quality control criteria for this filter were set as follows: (1) low-quality bases below phred quality 20 were trimmed from both ends of reads; (2) after the low-quality bases were trimmed, reads containing over two “N” were removed; (3) the reads with length shorter than 75 (for Dataset I) or 50 (for Dataset II) were removed; and (4) BWA35 related parameters were set as recommended. The filtering results are listed in Table 1. The clean reads were evaluated using FastQC v0.11.7 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/), and the assessment results were summarized and visualized using MultiQC v1.336 with the recommended configuration. Salmon ver. 0.9.137 was used to map the clean reads against the primary CDS from the genome (GenBank Assembely ID ASM160598v2) published by Zhang et al.22 to quantify the gene abundance as read counts. The default settings for Salmon were used. We applied the DESeq238 R package to normalize the read counts.

Table 1. Statistics of sequencing data for each sample.

| Sample | Data set | Sequencing strategy | Raw reads number | Clean reads number | Clean data rate (%) | Mapping rate (%) | Accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clean data rate = Clean reads number/Raw reads number. Mapping rates were calculated from the Salmon procedure. | |||||||

| PI1 | Dataset I | PE150 | 27660160 | 27542266 | 99.57 | 88.79 | SRR7221702 |

| PI2 | Dataset I | PE150 | 28518120 | 28393620 | 99.56 | 87.88 | SRR7221703 |

| PI3 | Dataset I | PE150 | 52075438 | 51809058 | 99.49 | 87.13 | SRR7221704 |

| PII1 | Dataset I | PE150 | 27285848 | 27121968 | 99.40 | 88.13 | SRR7221705 |

| PII2 | Dataset I | PE150 | 28178012 | 28029702 | 99.47 | 90.82 | SRR7221698 |

| PII3 | Dataset I | PE150 | 27530290 | 27410740 | 99.57 | 90.12 | SRR7221699 |

| PII4 | Dataset I | PE150 | 27772530 | 27659912 | 99.59 | 89.32 | SRR7221700 |

| PII5 | Dataset I | PE150 | 27628334 | 27437044 | 99.31 | 89.92 | SRR7221701 |

| PIII1 | Dataset I | PE150 | 27242838 | 27144468 | 99.64 | 87.77 | SRR7221696 |

| PIII2 | Dataset I | PE150 | 27002996 | 26922920 | 99.70 | 88.66 | SRR7221697 |

| PIII3 | Dataset I | PE150 | 27902586 | 27794040 | 99.61 | 88.45 | SRR7221709 |

| PIV1 | Dataset I | PE150 | 28311682 | 28225282 | 99.69 | 88.86 | SRR7221710 |

| PIV2 | Dataset I | PE150 | 28278086 | 28182784 | 99.66 | 88.69 | SRR7221711 |

| PIV3 | Dataset I | PE150 | 27896820 | 27815090 | 99.71 | 88.47 | SRR7221712 |

| PIV4 | Dataset I | PE150 | 27353690 | 27278754 | 99.73 | 88.98 | SRR7221713 |

| PIV5 | Dataset I | PE150 | 27885292 | 27775884 | 99.61 | 89.76 | SRR7221714 |

| PIV6 | Dataset I | PE150 | 28472368 | 28360984 | 99.61 | 89.52 | SRR7221715 |

| DR5 | Dataset II | PE90 | 48084156 | 47703558 | 99.21 | 87.50 | SRR7223299 |

| DR6 | Dataset II | PE90 | 50314908 | 49812640 | 99.00 | 89.40 | SRR7223298 |

| DR7 | Dataset II | PE90 | 50331572 | 49773744 | 98.89 | 89.89 | SRR7223301 |

| DR8 | Dataset II | PE90 | 50258420 | 49857612 | 99.20 | 89.73 | SRR7223300 |

| DR10 | Dataset II | PE90 | 47991832 | 47402820 | 98.77 | 89.03 | SRR7223296 |

| DR11 | Dataset II | PE90 | 50357650 | 49847644 | 98.99 | 89.57 | SRR7223295 |

| DR15 | Dataset II | PE90 | 50046760 | 49104418 | 98.12 | 87.68 | SRR7223297 |

Principal component analysis and heatmap illustration

The normalized read count values of each sample in the two datasets were employed in principal component analysis (PCA) with an online tool, three-dimension PCA (http://www.omicshare.com/tools/Home/Soft/seniorpca), using the default parameters. A heatmap for sample clustering of Dataset I was illustration with the R package PoiClaClu39.

Code availability

A R script for read count normalization and heatmap illustration is available in Figshare (Data Citation 2).

Data Records

The RNA-seq raw data of the two datasets were deposited at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive with BioSample accessions SAMN09267369–SAMN09267385 (Dataset I; Data Citation 1) and SAMN09269105–SAMN09269111 (Dataset II; Data Citation 1). Data Citation 2 contains the R scripts in this study. The files of gene abundance for the two datasets are deposited in Figshare (Data Citation 3). The heatmap for sample clustering of Dataset I is available in Figshare (Data Citation 4).

Technical Validation

RNA qualities

The quality of the total RNA was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyser 2100 (Agilent Technologies). The RNA samples with RNA integrity numbers higher than 7.0 were used to prepare RNA-seq libraries in this study. The RNA quality evaluations are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. RNA sample quality in this study.

| Sample | RIN | 28 S/18 S | OD260/280 | OD260/230 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI1 | 7.4 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| PI2 | 8.6 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 2.1 |

| PI3 | 7.5 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.4 |

| PII1 | 7.0 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| PII2 | 8.7 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 2.1 |

| PII3 | 8.6 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 |

| PII4 | 8.8 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| PII5 | 8.3 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 2.2 |

| PIII1 | 7.1 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| PIII2 | 8.4 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 2.1 |

| PIII3 | 8.4 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 2.1 |

| PIV1 | 7.9 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| PIV2 | 7.8 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| PIV3 | 8.2 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| PIV4 | 8.1 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.1 |

| PIV5 | 7.9 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| PIV6 | 8.8 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 2.1 |

| R5 | 8.9 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| R6 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| R7 | 8.4 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| R8 | 7.9 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| R10 | 8.0 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| R11 | 8.4 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| R15 | 8.5 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

Quality validation

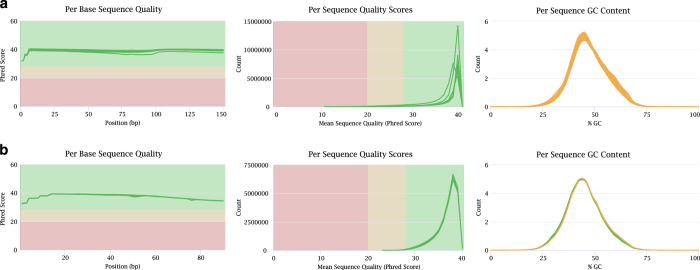

We applied FastQC to assess the RNA-seq clean data, including the mean per base quality scores, per sequence quality scores, and per sequence GC content. Summary plots are presented in Fig. 2. With respect to both datasets, the quality scores per base were higher than phred quality 30, and almost all sequences had a quality over 20. The GC contents of the samples from both datasets I and II showed a similar normal distribution. Moreover, the RNA-seq data had high mapping rates ranging from 87.13–90.82% (Table 1). These statistics indicated that high-quality RNA-seq reads were obtained for downstream analysis.

Figure 2. Quality assessment metrics for RNA-seq data.

The per base sequence quality (left), per sequence quality scores (middle), and per sequence GC content (right) across all samples of Dataset I (a) and Dataset II (b).

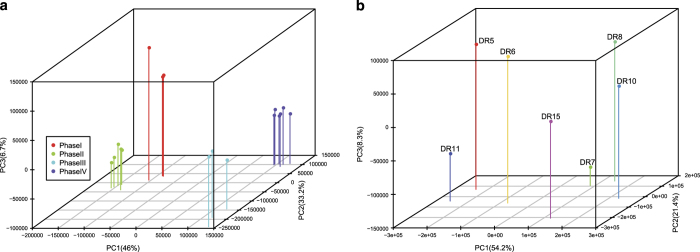

The PCA result (Fig. 3a) showed that the samples in dataset I clustered into four groups corresponding to the four phases in CAM, which was also supported by a sample clustering analysis (Data Citation 4). In Dataset II, the drought stress samples, including DR7, DR8 and DR10, clustered closely, and DR5, DR6 and DR11 were neighbors in the PCA plot (Fig. 3b). The distinctive pattern of samples in the analyses indicated that these transcriptome profiles were valuable for understanding the CAM pathways.

Figure 3. Three-dimensional PCA plots.

(a) Dataset I and (b) Dataset II.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Zou, L.-H. et al. RNA-seq transcriptomic profiling of crassulacean acid metabolism pathway in Dendrobium catenatum. Sci. Data. 5:180252 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.252 (2018).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Basic Research Fund of RIF (RIF2014-05) and the National Science & Technology Pillar Program during the Twelfth Five-year Plan Period (Grant No. 2013BAD01B0703; The Exploitation, Innovation and Utilization of Genus Dendrobium Germplasm Resources).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Citations

- 2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP132541

- Zou L.-H., et al. . 2018. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7040333

- Zou L.-H., et al. . 2018. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7040342

- Zou L.-H., et al. . 2018. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7041725

References

- Davis S. C., LeBauer D. S. & Long S. P. Light to liquid fuel: theoretical and realized energy conversion efficiency of plants using crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) in arid conditions. J. Exp. Bot 65, 3471–3478 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland A. M., Griffiths H., Hartwell J. & Smith J. A. C. Exploiting the potential of plants with crassulacean acid metabolism for bioenergy production on marginal lands. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 2879–2896 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S. C. et al. Toward systems-level analysis of agricultural production from crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM): scaling from cell to commercial production. New Phytol. 208, 66–72 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. et al. A roadmap for research on crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) to enhance sustainable food and bioenergy production in a hotter, drier world. New Phytol. 207, 491–504 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmond C. B. Crassulacean acid metabolism: a curiosity in context. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 29, 379–414 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. et al. Origin and mechanism of crassulacean acid metabolism in orchids as implied by comparative transcriptomics and genomics of the carbon fixation pathway. Plant J. 86, 175–185 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H. et al. Evolutionary history of PEPC genes in green plants: implications for the evolution of CAM in orchids. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 94, 559–564 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman J. C. Multiple isoforms of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase in the Orchidaceae (subtribe Oncidiinae): implications for the evolution of crassulacean acid metabolism. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 3623–3636 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J. et al. The genome sequence of the orchid Phalaenopsis equestris. Nat. Genet. 47, 65–72 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming R. et al. The pineapple genome and the evolution of CAM photosynthesis. Nat. Genet. 47, 1435–1442 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. et al. The Kalanchoë genome provides insights into convergent evolution and building blocks of crassulacean acid metabolism. Nat. Commun. 8, 1899 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Estrella R., Barkla B. J., Amezcua-Romero J. C. & Pantoja O. Day/night regulation of aquaporins during the CAM cycle in Mesembryanthemum crystallinum. Plant, Cell Environ 35, 485–501 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham P. E. et al. Transcript, protein and metabolite temporal dynamics in the CAM plant Agave. Nat. Plants 2, 16178 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brilhaus D., Bräutigam A., Mettler-Altmann T., Winter K. & Weber A. P. M. Reversible burst of transcriptional changes during induction of crassulacean acid metabolism in Talinum triangulare. Plant Physiol. 170, 102–122 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross S. M. et al. De novo transcriptome assembly of drought tolerant CAM plants, Agave deserti and Agave tequilana. BMC Genomics 14, 563 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyduk K., Ray J. N., Ayyampalayam S. & Leebens-Mack J. Shifts in gene expression profiles are associated with weak and strong crassulacean acid metabolism. Am. J. Bot. 105, 587–601 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman J. C., Tillett R. L., Wood J. A., Branco J. M. & Schlauch K. A. Large-scale mRNA expression profiling in the common ice plant, Mesembryanthemum crystallinum, performing C3 photosynthesis and Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM). J. Exp. Bot 59, 1875–1894 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wai C. M. et al. Temporal and spatial transcriptomic and microRNA dynamics of CAM photosynthesis in pineapple. Plant J. 92, 19–30 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Wai C. M., Ming R. & Yu Q. Diurnal cycling transcription factors of pineapple revealed by genome-wide annotation and global transcriptomic analysis. Genome Biol. Evol 9, 2170–2190 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. A. C. & Winter K. In Crassulacean acid metabolism - biochemistry, ecophysiology and evolution, eds Winter K. & Smith J. A. C. 427–436, Springer (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Yan L. et al. The genome of Dendrobium officinale illuminates the biology of the important traditional chinese orchid herb. Mol. Plant 8, 922–934 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G.-Q. et al. The Dendrobium catenatum Lindl. genome sequence provides insights into polysaccharide synthase, floral development and adaptive evolution. Sci. Rep 6, 19029 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen N. A. et al. Eddy covariance captures four-phase crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) gas exchange signature in Agave. Plant Cell Environ 39, 295–309 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W. & Zhang G. The photosynthesis pathway in leaves of Dendrobium officinale. Acta Phytoecol. Sin 27, 631–637 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., He D., Niu G. & Gao R. Concomitant CAM and C3 photosynthetic pathways in Dendrobium officinale plants. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 139, 290–298 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Winter K. & Holtum J. A. M. Facultative crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) plants: powerful tools for unravelling the functional elements of CAM photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 3425–3441 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Jiang W., Chen S., Mantri N. & Tao Z. Insights from the cold transcriptome and metabolome of Dendrobium officinale: global reprogramming of metabolic and gene regulation networks during cold acclimation. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1653 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X. et al. Analysis of the Dendrobium officinale transcriptome reveals putative alkaloid biosynthetic genes and genetic markers. Gene 527, 131–138 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C. et al. Identification of genes involved in biosynthesis of mannan polysaccharides in Dendrobium officinale by RNA-seq analysis. Plant Mol. Biol. 88, 219–231 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. et al. Transcriptome analysis of Dendrobium officinale and its application to the identification of genes associated with polysaccharide synthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 5 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. et al. iTRAQ and RNA-Seq analyses provide new insights into regulation mechanism of symbiotic germination of Dendrobium officinale seeds (Orchidaceae). J. Proteome Res. 16, 2174–2187 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y. et al. A transcriptome-wide, organ-specific regulatory map of Dendrobium officinale, an important traditional Chinese orchid herb. Sci. Rep 6, 1–13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cen P., Pan L.-J., Zhang M.-B., Fan G.-Q. & Cheng P. Preliminary study on extracting total RNA from polysaccharides-rich Dendrobium buds. Guangdong Agric. Sci 6, 162–164 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M. et al. Fastq_clean: An optimized pipeline to clean the Illumina sequencing data with quality control. In IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine 44–48, IEEE (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Li H. & Richard D. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewels P., Magnusson M., Lundin S. & Käller M. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 32, 3047–3048 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patro R., Duggal G., Love M. I., Irizarry R. A. & Kingsford C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417–419 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M. I., Huber W. & Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten D. M. Classification and clustering of sequencing data using a poisson model. Ann. Appl. Stat 5, 2493–2518 (2011). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP132541

- Zou L.-H., et al. . 2018. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7040333

- Zou L.-H., et al. . 2018. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7040342

- Zou L.-H., et al. . 2018. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7041725