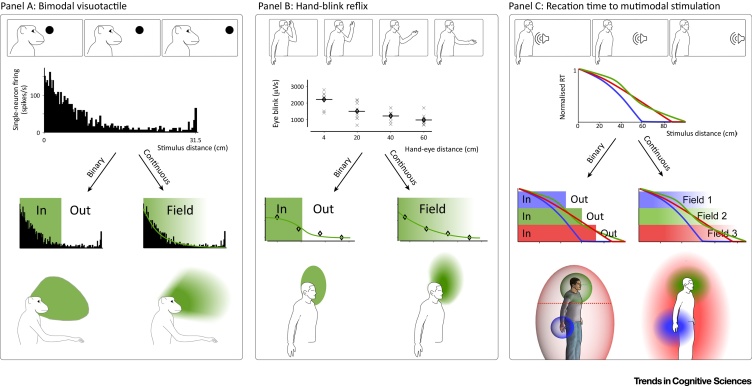

Figure 1.

Describing Peripersonal Space (PPS): Gradient or Boundary? Many behavioural and neurophysiological responses have been labelled as PPS measures because their magnitude increases with body proximity. However, even when clearly graded with proximity to a body part, PPS measures are often described using binary ‘in-or-out’ metrics and wording (left side of each panel). This approach often consists in choosing some cut-off value to define the PPS ‘size’. Examples of such cut-off values are the furthest distance at which consistent modulation is observed (A) and the midpoint of a fitted function (B,C). (A–C) show examples of how PPS data could be described as binary ‘in-or-out’ metrics [left side of (A–C)], but more faithfully reflect the data when displayed as a continuous, graded response field [right side of (A–C)]. (A) Bimodal visuotactile neurons fire more when visual stimuli are close to their tactile receptive fields [25]. However, as discussed in the main text, this is an oversimplified description. (B) The hand-blink reflex is elicited by stimulation of the median nerve at the wrist, and increases in magnitude when the hand is closer to the face [35]. (C) Reaction times (RT) to somatosensory stimuli on the face (green), hand (blue), and chest (red) are faster when auditory or visual stimuli are concomitantly presented closer to those body parts [38]. Other types of visuotactile and audiotactile integration have also been shown to increase in magnitude with proximity the body [87]. Data reproduced, with permission, from 9, 25, 88.