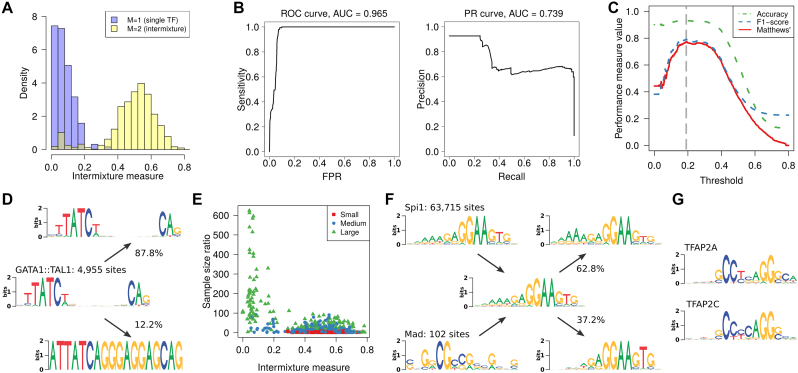

Figure 3.

Intermixture detection as binary classification. The task is to distinguish data sets containing binding sites of a single TF (M = 1) from those where binding sites of two TFs are intermixed (M = 2). (A) Histograms of intermixture measure for both classes normalized by the number of members of each class. (B) Classification performance with varying intermixture threshold according to ROC and PR curves. (C) Different aggregating performance measures as function of the intermixture threshold. The optimal threshold is marked by vertical dashed line. (D) Example of a data set that IMD classifies as intermixture, where the second component is a binding site that occurs within a transposable element and has thus been massively amplified in the genome. (E) Dependence of the intermixture measure on the disparity of the sample sizes of the intermixed data sets. The legend indicates the total sample size, distinguishing between small (N < 1000), medium and large (N > 10 000). (F) Example where the sample size disparity is so high that the sequence logo of the intermixture is virtually identical to that the larger data set (Spi1). De-mixing then reveals only heterogeneities with the Spi1 motif instead of recovering the two ground-truth PWMs. (G) Examples for data sets that are so similar that inter-motif heterogeneity appears as intra-motif heterogeneity.