ABSTRACT

Many marine larvae begin feeding within a day of fertilization, thus requiring rapid development of a nervous system to coordinate feeding activities. Here, we examine the patterning and specification of early neurogenesis in sea urchin embryos. Lineage analysis indicates that neurons arise locally in three regions of the embryo. Perturbation analyses showed that when patterning is disrupted, neurogenesis in the three regions is differentially affected, indicating distinct patterning requirements for each neural domain. Six transcription factors that function during proneural specification were identified and studied in detail. Perturbations of these proneural transcription factors showed that specification occurs differently in each neural domain prior to the Delta-Notch restriction signal. Though gene regulatory network state changes beyond the proneural restriction are largely unresolved, the data here show that the three neural regions already differ from each other significantly early in specification. Future studies that define the larval nervous system in the sea urchin must therefore separately characterize the three populations of neurons that enable the larva to feed, to navigate, and to move food particles through the gut.

KEY WORDS: Sea urchin, SoxC, Sip1, Soxb1, Neurogenesis, Proneural

Summary: Patterning signals in the three territories in which neurogenesis is initiated during sea urchin gastrulation differentially affect proneural expression of six transcription factors resulting in three unique specification trajectories.

INTRODUCTION

The bilaterally symmetrical larva of the sea urchin develops a nervous system that begins functioning when the larva begins to feed, which in Lytechinus variegatus occurs between 24 and 48 hours post fertilization (hpf). By that time, 40-50 neurons constitute the nervous system composed of about four serotonergic, 30-35 cholinergic and five to ten dopaminergic neurons (Garner et al., 2016; Hinman and Burke, 2018; Slota and McClay, 2018). These neurons differentiate in three locations in the larva. The serotonergic neurons differentiate at the anterior end of the larva in the oral hood (Yaguchi et al., 2000; Angerer et al., 2011). Most of the cholinergic neurons are distributed within the ciliary band (CB), which is located between the dorsal and ventral ectoderm (Nakajima et al., 2004; Burke et al., 2006b). A population of neurons that are dopaminergic and cholinergic resides just outside the CB (Slota and McClay, 2018). Cholinergic and dopaminergic neurons also differentiate just outside the gut tube in the regions of the sphincters separating the three gut compartments (Wei et al., 2011; L. Slota and D.R.M., unpublished observations).

The sea urchin larva uses its simple nervous system for a number of functions. Coordinated ciliary movements create a current of water that propels the embryo forward, and synchronized ciliary reversals divert the current towards the mouth for the capture of food particles (Strathmann, 2007). A number of neurons that differentiate within the CB presumably coordinate these functions (Nakajima et al., 2004; Burke et al., 2006b). Neurons also control swallowing of food in the foregut by controlling muscular peristalsis that moves the food particles to the gut chambers. The gut neurons have been proposed to originate from endodermal precursors (Wei et al., 2011). Serotonergic neurons at the anterior end of the larva were reported to coordinate directional swimming (Yaguchi and Katow, 2003) as serotonin-deficient embryos ‘crawled’ rather than swam (Katow et al., 2007). More neurons are added later as the larva feeds but it starts behaving with this very limited nervous system.

In many animals, a significant number of neurons arise from migratory populations of cells (e.g. neural crest cells in vertebrates or ventral neurons in amphioxus; Kaltenbach et al., 2009). In chick and mouse, posterior neuromesoderm progenitors migrate from their site of origin (Tsakiridis et al., 2014; Gouti et al., 2014; Henrique et al., 2015; Kimelman, 2016; Wymeersch et al., 2016). Because neurons differentiate at three different locations in the sea urchin embryo, lineage analysis was necessary to establish whether those neurons arose locally or emigrated to one or more of the other locations. That analysis, reported below, establishes that neural progenitors are specified at the three locations without cell migrations. This is an obvious contrast to vertebrate neurogenesis where neural precursors migrate large distances to establish the sensory, sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

Several studies addressing sea urchin neural specification have begun to disclose the mechanisms behind neurogenesis. Experimentally, in the absence of Nodal signaling, the anterior neural ectoderm region (ANE) (Angerer et al., 2011) expands and differentiates as neural tissue (Yaguchi et al., 2006; Bradham et al., 2009), suggesting that Nodal normally acts in some way to limit the size of the ANE domain. Based on that signaling, an ancestral specification subcircuit regulating neural induction was proposed by Saudemont et al. (2010), wherein neural ectoderm was hypothesized to be the default condition in the absence of transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling. That idea is similar to findings in vertebrate embryos, in which the tendency for nascent ectoderm to adopt a neural fate in the absence of BMP signaling is termed the ‘default model’ of neural induction (Hemmati-Brivanlou and Melton, 1997; reviewed by Stern, 2005, 2006). Experimental support for this model in sea urchins was demonstrated by showing that animal hemispheres, isolated during early cleavage, become strongly neural, suggesting a default proneural state in the animal hemisphere. A partial explanation for that phenomenon was shown to also involve exclusion of Wnt signaling from the anterior end of the embryo (Angerer et al., 2000, 2011; Angerer and Angerer, 2003; Yaguchi et al., 2006). However, signaling data can be misleading. For example, neurogenesis in vertebrates occurs anteriorly in the absence of Wnt, but posteriorly Wnt is present and necessary for neurogenesis. In a similar fashion, as there are three sites of neurogenesis in the sea urchin it could be that a ‘default state’ is different in each location. Thus, to understand how neurogenesis is initiated in the sea urchin embryo it is necessary to determine how patterning establishes each of the three regions.

Perturbation analyses of Nodal, BMP, FGF and Wnt6 indicate that each region of neurogenesis is initiated downstream of different patterning regimes. Perturbation of proneural transcription factors plus Notch/Delta signaling (involved in restricting the number of neurons arising from progenitors) indicate that each population of neural progenitors deploys a somewhat distinct specification trajectory with little in common between the three territories.

RESULTS

Transcription factors involved in early neurogenesis

Neurogenesis occurs in three domains in the sea urchin embryo. The ANE domain, also called the animal pole domain (APD) (Bisgrove and Burke, 1986; Wei et al., 2009; Garner et al., 2016) (Fig. 1A), is characterized by specification of four to five serotonergic neurons. A number of neurons differentiate in the CB and in the post oral region just outside the CB (Garner et al., 2016; Slota and McClay, 2018) (Fig. 1A). The gut also harbors neurons at the mouth and sphincters, and these were reported to arise from early endoderm (Wei et al., 2011) (Fig. 1A). Here, we refer to that domain as ‘endomesoderm’ (EM) because it originates at the boundary between what will become the two germ layers.

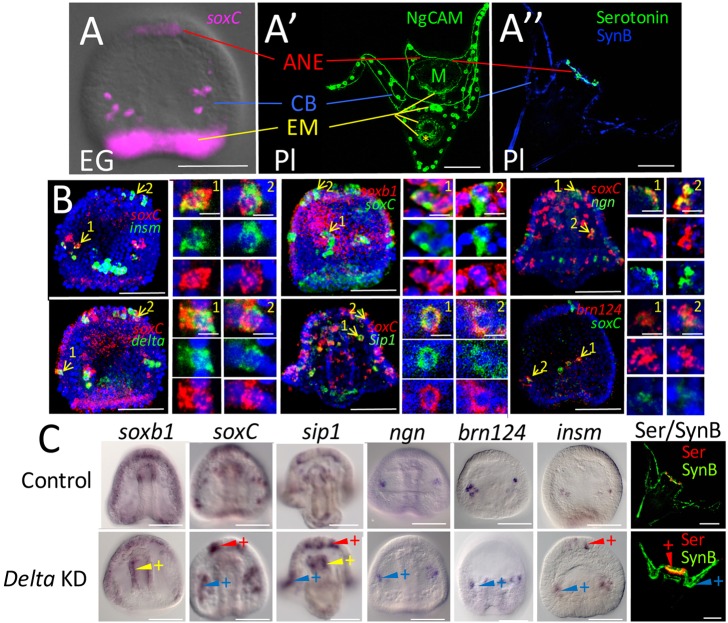

Fig. 1.

Neurogenesis in early development. (A) Expression of soxC, a proneural gene, occurs in three domains: anterior neuroectoderm (ANE), ciliary band (CB) and endomesoderm (EM). EG, early gastrula. (A′) The ANE domain specifies a population of neurons in the oral hood of the pluteus (Pl) larva. The CB domain specifies neurons that populate the CB and post oral domain. Neurons arising from the EM eventually populate the mouth and sphincters that separate the foregut, midgut and hindgut. The yellow lines in A′ point to those three sphincters, in addition to a ganglion on the posterior side of the mouth (M). A yellow asterisk marks the location of the anus. (A″) A pluteus larva showing the serotonergic neurons in the oral hood and synaptotagmin B-stained neurons around the CB. A comparison of the two larvae in A′ and A″ shows that NgCAM-stained neurites are the same as those recognized by the synaptotagmin B-stained neurites (see also Fig. S6). In addition, NgCAM stains the EM neurons more readily. The NgCAM antibody also stains the cell membranes of skeletogenic cells (Fig. S6). Skeletogenic cells, being non-neural, provide an internal control for perturbation experiments below. As a convention for this paper, ANE domain effects will be illustrated in red, CB domain effects will be illustrated in blue and EM effects will be illustrated in yellow. (B) Proneural genes are expressed in the same cells and with cells expressing delta. In each case, two cells in a single layer (2 µm) of the confocal stack are magnified to show co-expression of proneural genes in the same cell. Examples were chosen from two different domains where possible. Some cells expressed only one of the two markers. We assume the lack of co-expression in those cases reflects differential timing of expression of the proneural genes. (C) Knockdown (KD) of delta expression causes each of the proneural transcription factor genes to be expressed in an increased number of cells relative to controls at the same stage in the territories where these genes are expressed. The red arrowheads with a plus sign indicate an embryo in which a transcription factor is expressed in more cells of the ANE than control. A blue arrowhead with a plus sign indicates additional CB cells expressing a proneural marker, and a yellow arrowhead with a plus sign indicates an increased number of EM proneural cells expressing the marker. In each case, the result reflects a pattern seen in at least 80% of embryos in a single experiment (>100 embryos per treatment) and each experiment was repeated at least three times (see Materials and Methods for scoring details). The images in the right panels show that following delta knockdowns more serotonergic (Ser) and synaptotagmin B (SynB)-positive neurons differentiate relative to controls. Scale bars: 50 µm (4 µm for single cell images).

As the goal of this investigation was to examine how neurogenesis is launched in the sea urchin embryo, we first screened known neural markers to find a group that are expressed early in one or more of the three neural territories (combining the CB and post oral territories). We cloned and determined spatiotemporal expression patterns for 43 genes, most of which had been annotated in sea urchins (Burke et al., 2006a) or activated early in neurogenesis in either Drosophila or vertebrates (Table S1). From that screen, six proneural transcription factors were selected: three that are expressed in all three neural territories (soxC, sip1, soxb1) and three that are expressed in one or two of the territories but not all three, at least during the proneural phase of specification (brn124, insm, ngn) (Fig. S1). Two other genes, ac-sc and ato, also appeared to be proneural but were not used because their expression levels were too low for reliable scoring using the in situ hybridization approach taken in these experiments. The criteria for establishing that these transcription factors were proneural, was that they should be expressed prior to, or coincident with delta expression because Delta-Notch signaling is involved in restricting the number of neurons in a territory after proneural specification has begun (Artavanis-Tsakonas et al., 1991; Fehon et al., 1991; Mellott et al., 2017). Second, double-label in situ hybridization analysis established that each of the early-expressed genes were co-expressed with soxC, an established early-expressed proneural gene (Garner et al., 2016) (Fig. 1B and Fig. S2). soxb1 was a special case in that it is involved in early specification of ectoderm (Barsi et al., 2015) and is eliminated post-translationally from the EM (Angerer et al., 2005). Double in situ hybridization with soxC indicated that the pattern of soxb1 expression somehow contributes to the earliest proneural soxC expression, and that increased soxb1 expression occurs in the earliest proneural cells (Fig. S2).

The proneural genes we examined are activated at different times in the three territories. CB cells are activated early after mesenchyme blastula and the ANE territory initiates neurogenesis by the midgastrula stage. soxC is activated during cleavage at the vegetal pole, and at some time during gastrulation EM cells initiate proneural specification (Fig. S1). Thus, each territory initiates neurogenesis at a different time, and within each territory proneural gene expression varies to some extent. Neurogenin (Ngn), for example, is not expressed until mid-gastrula in the CB proneural progenitors (Fig. S1; Slota and McClay, 2018). Thus, there is not a single time that proneural specification is initiated. Rather, specification begins in some cells at mesenchyme blastula with others initiated during gastrulation or even later as additional neurons are added to the nervous system.

Delta-Notch signaling is often involved in restriction of the number of proneural cells that go on to differentiate. Thus, an additional criterion for inclusion of a transcription factor as proneural is that knockdown of delta should expand the number of cells expressing the proneural transcription factor. That outcome was seen for each of the six candidate transcription factors, and antibody staining for neurons indicated the presence of excess neurons in delta knockdowns (Fig. 1C). Thus, soxC, sip1, soxb1, brn124, insm and ngn were used as the proneural markers for subsequent experiments. It should be noted that brn124, insm and ngn are proneural in the CB territory but later are activated in the other territories after the Delta restriction.

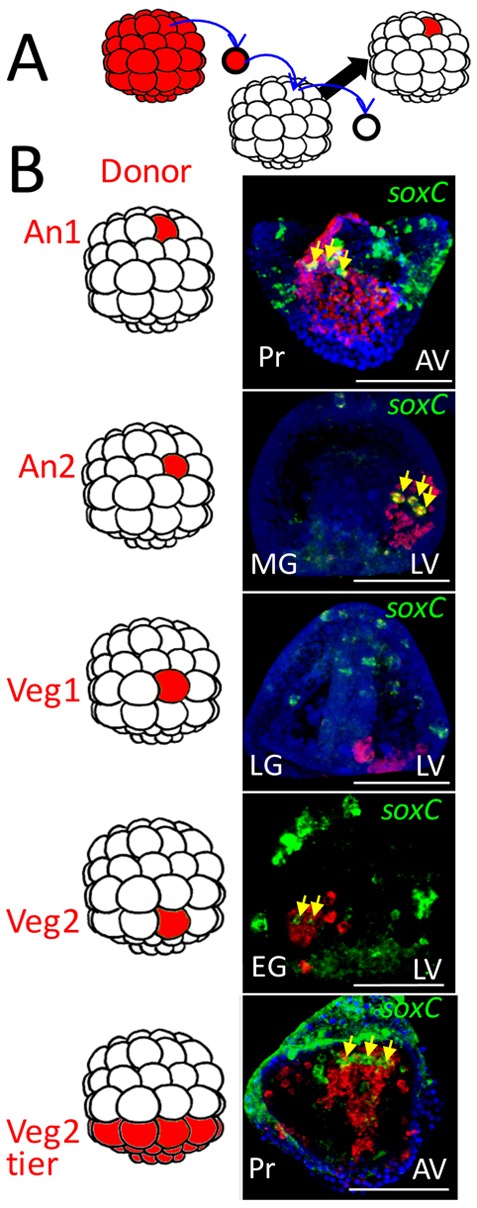

Neurogenesis occurs locally in each of the three domains

Across the animal kingdom, neural precursors often originate in one location and migrate to distant sites. Therefore, we wondered whether neural precursors in the sea urchin embryo undergo large-scale migrations, or whether neural specification begins locally in the three territories. In an earlier study, KikGR, a photoconverting fluorophore, was used to photoconvert cells in the ANE domain. Photoconverted cells were not detected later in the gut (Wei et al., 2011). It was concluded that endoderm neurons had not originated from cells that had migrated from the ANE. To further determine whether migration occurred to establish one or more of the three neural territories, we chose a cell recombinant approach. Importantly, it was necessary to determine whether a migrating cell was neural. The stereotypic cleavage pattern in sea urchin embryos results in six easily recognized tiers of cells along the anterior-posterior axis after the sixth cleavage (Fig. 2). Recombinants were produced in which a single cell, or an entire tier from an RFP-labeled embryo, was transplanted to an equivalent location after removal of a host cell or tier from the host embryo (Fig. 2). Because soxC is expressed in all proneural cells, and is expressed continuously until neural differentiation (Yankura et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2015; Garner et al., 2016), we scored the experiment by doing an in situ analysis to identify red cells (territory of lineage origin) and green cells (proneural soxC) at the end of gastrulation or at the prism stage when we knew that proneural development had been initiated in all three territories. We did not include the micromeres in the experiment because their fate was known to be non-neural.

Fig. 2.

Cell lineage analysis indicates that neurogenesis is initiated in three locations in the embryo. (A) Schematic of the experimental procedure. At the 60-cell stage, a single RFP-expressing cell (red) is transplanted to an equivalent location in an unlabeled 60-cell stage embryo. The donor is from the same tier of cells as the cell it replaces as shown in the diagrams to the left of the images in B (the top four tiers are named An1, An2, Veg1 and Veg2 as indicated (the bottom two tiers, the large and small micromeres, have known fates and so were not considered). (B) Embryos were fixed at different stages and double in situ hybridization performed to identify soxC expression (green), which by this time exclusively marks neural progenitors. The patch of cells derived from the RFP donor is stained red. The yellow arrows point to soxC-positive cells that also are stained red, thus neural lineage progeny of the labeled donor cell. Of more than 80 cases scored we observed no double-labeled neural progenitors outside the patch of donors, including the bottom image in which the entire Veg2 tier was transplanted. In that image, as expected, a number of cells migrate from the patch but none of the migrants is both red and green. In each case, a portion of a confocal stack is shown at the level of double-labeled cells, if present. Transplant cases scored: An1, n=3; An2, n=18; Veg1, n=25; Veg2, n=30; Veg2 tier, n=4. AV, animal view; EG, early gastrula; LG, late gastrula; LV, lateral view; MG, midgastrula; Pr, prism. Scale bars: 50 µm.

As expected, many of the RFP-labeled Veg2 cells migrated because that tier later gives rise to pigment cells and several types of immune cells that migrate throughout the blastocoel and dorsal ectoderm. However, the red/green soxC/RFP double-positive Veg2 cells remained within the EM domain (Fig. 2). We conclude that EM neural cells originate and remain in that domain.

We failed to observe any neural progenitors arising from the Veg1 domain in 25 cases scored. We conclude that cells from the Veg1 domain rarely, if ever, contribute to neurogenesis. From An2 transplanted cells, a number of soxC/RFP double-positive neural progenitors were observed and each became part of the CB or post oral domain. All double-positive cells remained within or immediately proximal to the patch of labeled ectoderm, again indicating that this population initiates neurogenesis locally. Finally, soxC/RFP double-positive An1 cells gave rise to the ANE progenitors and no double-labeled An1 neural precursors were observed outside this domain. Thus, in each of more than 80 transplants resulting in more than 700 labeled soxC cells, the double-labeled cells were found only within the patch of RFP-labeled cells. Thus, neural specification initiates locally in the three domains. The analysis does not rule out short-range migrations within the domains, especially within the CB domain where migrations within the dimensions of the RFP patch could occur and would be missed by this analysis. The analysis also does not eliminate the possibility that some later neural precursors migrate in the pluteus (at times after our analysis), though such migration would not affect our conclusion that neurogenesis occurs in three domains in the sea urchin embryos.

Prepatterning of the three domains of neurogenesis

We next investigated whether early neurogenesis occurred similarly or differently in the three locations. Neurogenesis occurs as a salt- and-pepper selection of cells in each domain so neural progenitors are surrounded by cells that are prepatterned locally by earlier and coincident specification and signaling. In each domain, the patterning could act directly on the neural progenitors, or it could act indirectly on the field of surrounding cells (or both). To investigate the impact of those patterning signals on neurogenesis, patterning signals were perturbed and the outcome recorded for each of the three domains.

Nodal and BMP signaling differentially affect early neurogenesis in the three territories

Nodal and BMP are crucial signals for ventral and dorsal ectoderm specification (Duboc et al., 2004) and are involved in prepatterning of all three germ layers (Duboc et al., 2010). Knockdown of Nodal with a morpholino (MO) eliminated the CB soxC-positive cells as well as expression of the other proneural transcription factors in the CB/post oral domain (brn124, sip1, insm, ngn and soxb1) (Fig. 3). At differentiation, there was a loss of neurons in the CB domain (Fig. 3). At the same time in the ANE territory, knockdown of Nodal resulted in an expanded expression of soxC and sip1, and expanded numbers of serotonergic neurons in the ANE (Fig. 3). Overexpression of nodal or knockdown of Lefty, the antagonist of Nodal, produced the opposite effects, i.e. excess soxC-expressing clusters in the future CB and absence of soxC-expressing proneural cells in the ANE (Fig. S3). Overexpression of Nodal resulted in absence of serotonergic neurons in the ANE and excess CB neurons (in this case the CB is displaced in a radialized embryo) (Fig. 3, Fig. S3). Loss of Nodal had a more modest outcome on early EM specification, although at differentiation there were no EM neurons surrounding the gut sphincters (Fig. 3).

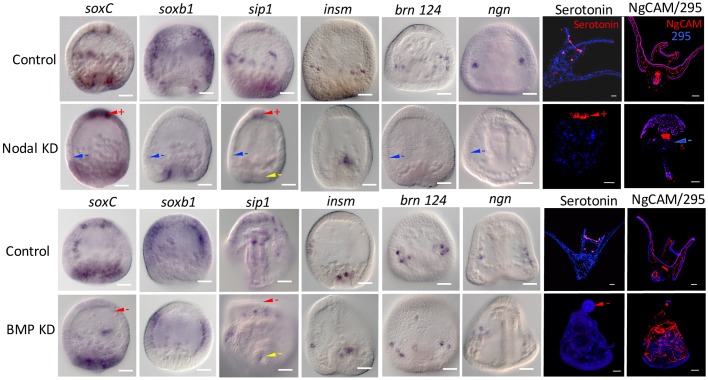

Fig. 3.

Nodal and BMP perturbations show differential effects on expression of proneural markers in the three territories. Embryos were stained for expression of proneural markers after knocking down expression of Nodal (top) or BMP (bottom), and compared with expression of that marker in controls fixed at the same stage. Interpretations of the effect on marker expression in each of the three neural domains is shown with arrowheads: red for the ANE domain; blue for the CB domain; yellow for the EM domain. A minus sign indicates marker expression is reduced or absent compared with controls in that territory. A plus sign indicates increased expression of a marker relative to controls in that territory. Each interpretation is based on at least three independent experiments in which more than 80% of the perturbants show the phenotype scored (see Materials and Methods for detailed scoring methods). The two right-hand panels show antibody staining of differentiated serotonergic neurons and NgCAM-stained non-serotonergic neurons. 295 is an antibody that stains the CB. As expected, the Nodal and BMP knockdowns radialized the embryos in addition to the effects on neurogenesis. Scale bars: 20 µm.

Previous studies showed that elimination of BMP2/4 allowed the CB to expand and cover the entire dorsal half of the embryo, whereas ectopic overexpression of BMP2/4 blocked Nodal signaling (Bradham et al., 2009). The ectopic BMP2/4 ligand is expressed prior to endogenous nodal activation, and, as a consequence, Nodal fails to establish its community effect (Bradham et al., 2009). Once the Nodal community effect is established, BMP2/4 expression no longer has a strong impact on the ventral half of the embryo even if BMP2/4 is present in the absence of Chordin (Bradham et al., 2009). In neural patterning, when BMP2/4 was knocked down, the ANE domain failed to express proneural soxC, or sip1, and there was a larger clearance of soxb1 from that region than in controls (Fig. 3). Many CB and EM proneural markers were retained or only delayed in expression in bmp2/4 morphants, as expected, as in those embryos Nodal expression occurred. When stained with differentiation markers, BMP2/4 knockdown resulted in the absence of anterior serotonergic neurons whereas CB and EM neurons were present in the radialized embryos (Fig. 3). Overexpression of bmp2/4 eliminated expression of soxC in the CB domain, increased soxC expression in the ANE and led to augmented numbers of serotonergic neurons in the ANE domain, which was the same response seen with the Nodal knockdowns (Fig. S3). Loss of Chordin and its chaperone function needed to transport BMP2/4 to the dorsal side resulted in loss of serotonergic neurons (Fig. S3).

As Nodal and BMP signaling affect dorsoventral compartmentalization of non-skeletal mesoderm and endoderm (Duboc et al., 2010), perhaps it was not surprising that the EM domain of neural specification was also sensitive to Nodal and BMP signaling though less so than either of the other two domains. Thus, the three domains of neurogenesis responded differently from one another in response to Nodal and BMP signaling.

Wnt and FGF signaling differentially affect neurogenesis in the three domains

We prescreened Wnt3, Wnt5, Wnt8 and Wnt16 (Fig. S4) in addition to Wnt6. Of those, only Wnt6 perturbations had significant and consistent effects on early neurogenesis. Loss of Wnt6 resulted in reduced proneural transcription factor expression in all three domains (Fig. 4). Thus, for this signal the three territories had a similar response. The Wnt6 knockdown had a strong and consistent effect on expression of the delta ligand (Fig. S5). In the absence of Wnt6, delta was overexpressed in the EM domain suggesting that Wnt6 normally represses delta expression in this region.

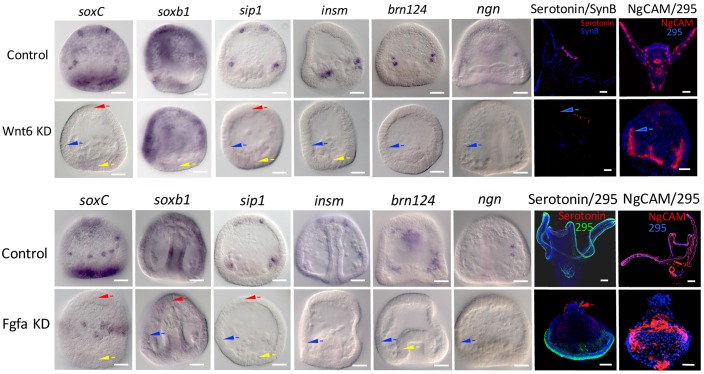

Fig. 4.

Wnt6 and FGFa knockdowns differentially affect proneural neurogenesis. Wnt6 (top) and FGFa (bottom) were knocked down and the expression of the six proneural transcription factors scored during proneural specification at gastrulation. In each case, arrowheads record interpretations of the knockdown effect (as described in Fig. 3 legend) on a proneural domain at the time embryos were scored. In the two right-hand panels serotonin, NgCAM and a CB-staining antibody (295) are reported in 24 hpf control and knockdown larvae. The NgCAM stain in the Wnt6 knockdown shows skeletogenic cells but no neurons. Scale bars: 20 µm.

Perturbation of FGFa (Rottinger et al., 2008) affected early neurogenesis of the three domains differently (Fig. 4). In the ANE domain, reduction in FGFa signaling greatly altered neurogenesis by reducing expression of three early proneural genes and no serotonergic neurons differentiated. Reduction of FGFa reduced expression of CB markers except for expression of soxC and had a mixed and different outcome in the EM domain. FGFa loss radialized the embryos resulting in the CB being moved to a zone on the bottom of the embryo. Despite the negative effect on some proneural genes in the CB, some neurons differentiated in the radialized FGFa-knockdown embryos in this region, as seen in the embryos stained with NgCAM (Fig. 4).

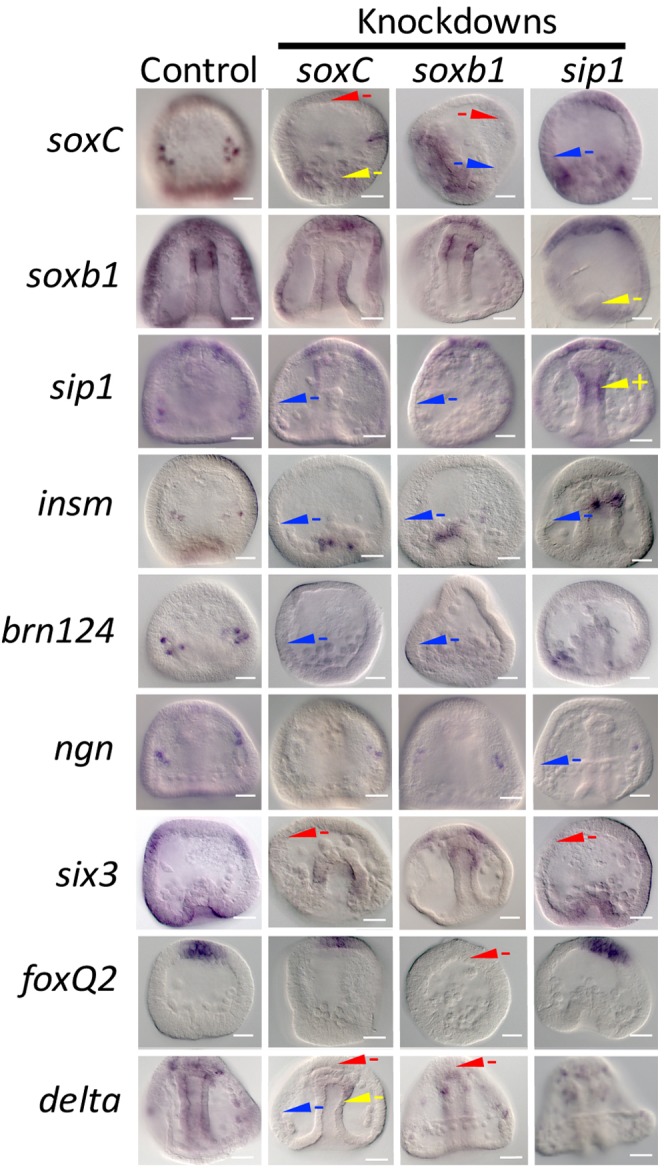

Gene regulatory network states for the three domains differ significantly in how they are initiated

The final question addressed was whether neural progenitors in the three territories were specified as proneural via similar mechanisms. To address this question, we added data from transcription factor knockdowns of soxC, sip1 and soxb1, the three transcription factors expressed in all three territories. Expression of the six proneural transcription factors shows that the response to knockdown of soxC, sip1 or soxb1 differs when the three territories are compared (Fig. 5). soxC knockdown, for example, affected soxC expression in the ANE and EM but there was little effect in the CB territory. soxb1 expression, was little affected by soxC or soxb1 knockdown but its expression was affected by sip1 knockdown in the EM and probably in the CB. six3 and foxQ2 were included in this experiment because they are well-known territorial markers in early specification of ectoderm and, in the case of six3, endoderm territories, and have been shown to be involved in neural specification (Wei et al., 2009; Range and Wei, 2016). delta was included in this experiment as a knockdown read-out as well as its proneural expression contributes to the regulatory states.

Fig. 5.

Proneural transcription factor knockdowns differentially affect expression of other proneural and territorial markers. soxC, soxb1 and sip1 were knocked down with MOs and embryos were scored for marker expression at multiple stages of development. The expression of each marker was compared with controls at the same stage and interpretations were recorded for each of the three neural domains (as described in Fig. 3 legend). In each case, the examples shown represent at least 80% of the embryos resulting from the same perturbation with more than 100 embryos scored in each case with at least three replicates performed. Scale bars: 20 µm.

Given the knockdown phenotypes seen both with the patterning inputs from Fig. 3 and 4 and Fig. S5, plus the transcription factor knockdowns in Fig. 5, gene regulatory network (GRN) models were assembled to illustrate the data obtained for each of the three domains. Fig. 6 shows GRN states operating in each of the three domains using the assumption that if expression of a gene is downregulated in response to perturbation of an upstream gene, then that downstream gene somehow requires function of the upstream gene product for expression. If expression of the downstream gene is higher in the absence of the upstream function, then it is likely that the upstream function somehow represses the downstream expression (Davidson et al., 2002a,b). Fig. 6 also shows a fourth GRN model based on those connections that were ‘in common’ to all three domain GRNs. As can be seen, a relatively small number of connections are in common. The models depict inputs as direct into transcription factor targets though in reality many of these inputs are likely to be indirect. The models also are compressed temporally to reflect single GRN states despite the fact that proneural specification occurs at different times in each of the domains and within each model transactions likely occur at different times. We attempted to correct for cases in which a perturbation simply caused a delay in expression by analyzing outcomes at several stages through late gastrula. In several cases, one or more of the neural progenitor transcription factors was expressed in domains other than neural. We tried to account for neural only, rather than the presumed non-neural expression in the model. The appearance of brn124 expression in the EM, for example, may have reflected early expression of endodermal brn124, which is proposed to be activated in endoderm during invagination of the archenteron (Yuh et al., 2005), and may contribute to endoderm specification as well as neural.

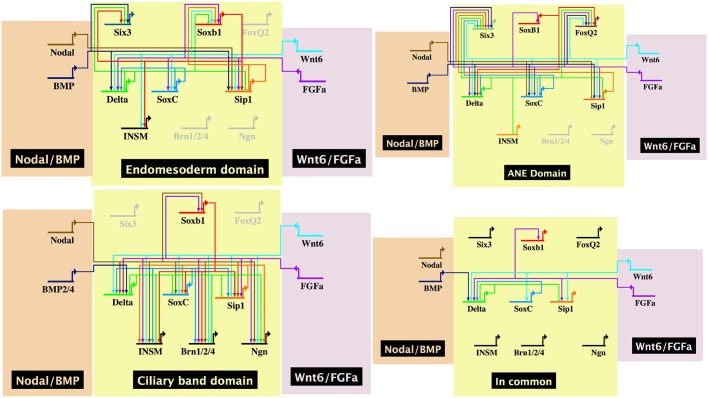

Fig. 6.

GRN models in BioTapestry of each proneural domain and a model reflecting ‘in common’ connections. Data were drawn from perturbations shown in Figs 1,3-5 and Fig. S5. In each case, inputs could be direct or indirect. The ‘In Common’ model shows all connections that are common to specification in all three territories.

Even with these several caveats, a comparison of signaling and transcription factor inputs into the several proneural genes shows that proneural specification in each of the three domains of neurogenesis differs significantly with only a few of the connections found in all three domains (Fig. 6, ‘In common’ GRN). We conclude that the three domains of neurogenesis in the sea urchin embryo are initiated by different signaling inputs and the proneural specification resulting from those inputs also differs.

DISCUSSION

Nervous systems originate in multiple locations in many animal embryos

Three sites have been described previously as locations where neurogenesis occurs (Angerer et al., 2011; Wei et al., 2011), and the present data confirm this and indicate that neural specification is initiated at these three sites rather than as a result of the import of neural precursors from elsewhere. The differential origin of nervous systems in embryos is a feature seen across the animal kingdom. In Cnidaria, for example, proneural specification occurs distinctly in ectodermal and endodermal tissues (Layden et al., 2012; Nakanishi et al., 2012; Watanabe et al., 2014). Acoel neural development arises from three cell lineages (Henry et al., 2000; Hejnol and Martindale, 2009). A recent study examining a number of invertebrates for neural origins noted a relative lack of conserved patterning mechanisms used during early neurogenesis (Martín-Durán et al., 2018). Furthermore, within clades, differential specification establishes distinct components of the nervous system. In vertebrates, for example, neural specification occurs distinctly in the neural tube, in a subset of neural crest cells, and in the posterior neural mesoderm (Gouti et al., 2014; Tsakiridis et al., 2014; Wymeersch et al., 2016). In Drosophila, recent studies on transcriptomes of different neuronal cell types indicate many distinct expression profiles (Yang et al., 2016). Thus, regulation of neural specification across the animal kingdom shares some properties, but even within single organisms the variation in specification of local populations of neural progenitors means that neural gene regulatory networks are diverse in their origins.

Vertebrate neural crest progenitors and neural mesoderm derivatives migrate some distance from their sites of origin to populate nervous system territories. Those migrations are common in other deuterostomes as well. In amphioxus, for example, peripheral neurons originate in the ventral ectoderm, and migrate to their intended destinations (Rasmussen et al., 2007; Kaltenbach et al., 2009). A few neural progenitors in tunicates arise from neural plate borders and migrate along the notochord (Stolfi et al., 2015). Hemichordate neurogenesis eventually results in the formation of dorsal and ventral trunk cord formation along the midline, but whether the scattered neurons that differentiate arrive there following a migration or whether there is rapid differentiation of resident neural progenitors is not known (Cunningham and Casey, 2014). Migrations have not been examined in larvae or after metamorphosis in echinoderms so one cannot rule out migrations at some stage in the life of sea urchins but the lineage analysis indicates that neural origins in sea urchin embryos are local.

The Delta-Notch restriction

Early work on sea urchin specification showed that Delta-Notch signaling was necessary for induction of the mesoderm (Sherwood and McClay, 1997, 1999, 2001; Sweet et al., 2002). More recently, the Delta-Notch pathway has also been shown to be involved in early neurogenesis of echinoderms (Yaguchi et al., 2012; Yankura et al., 2013; Burke et al., 2014) and other non-vertebrate deuterostomes (Pasini et al., 2006; Rasmussen et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2012). As originally discovered in Drosophila, Delta was found to be upregulated at the time proneural cells underwent lineage restriction (Xu and Artavanis-Tsakonas, 1990; Heitzler and Simpson, 1991; Campos-Ortega, 1993). One Delta-expressing cell became neural whereas surrounding cells became epidermal via signaling through Notch. Delta loss-of-function mutations produced excess neurons. Fig. 1C shows a similar effect of Delta knockdown on neurogenesis in the sea urchin. There was an excess number of neural precursors and differentiated neurons, exactly what would be predicted by an experimental absence of a Notch-Delta proneural restriction mechanism. The absence of sufficient Delta protein causes an increase in the number of soxC-positive neural progenitors and also results in a high number of delta-positive cells (Fig. S4).

Neurogenesis in the three domains occurs with differing responses to patterning signals

A number of signals establish the patterning of territories in which neurons are specified. Perturbation results, when modeled, show that the proneural response to those signals largely differs in the three domains examined here (Fig. 6). Increased Nodal expression, for example, restricts neural specification in the ANE (Yaguchi et al., 2007, 2012; Duboc et al., 2008). The CB domain, by contrast, requires Nodal signaling for proneural specification as loss of Nodal eliminates CB neurons whereas loss of Lefty expands the Nodal signal and, correspondingly, increases the number of CB neural progenitors (Fig. 3, Fig. S3). Nodal perturbations also have an impact on the EM domain though the extent of that impact is harder to assess because at the time Nodal influences the EM, soxC and sip1 are expressed more broadly than their later restricted expression in proneural cells.

BMP2/4, the signal that normally is necessary for dorsal ectoderm specification in the sea urchin (Duboc et al., 2004), also differentially influences specification of the neural domains (Fig. 3, Fig. S3). Knockdown of BMP2/4 negatively impacts specification of neural progenitors in the ANE domain. Nodal, because it diffuses only a short distance and is expressed very early, probably acts not in the ANE domain, but earlier in a more posterior region of the ectoderm to help restrict the size of the future ANE domain to the very anterior end of the embryo. Recently, Yaguchi et al. (2016) reported that Nodal is required to suppress the serotonergic neural fate on the ventral side of the ANE domain. Our data agree with this and Fig. 3 and Fig. S3 show also that perturbations of Nodal and BMP have opposite effects on both initial specification of CB neural progenitors and ANE neurons. In an earlier study, Yaguchi et al. (2010) concluded that Nodal must be excluded from the CB for neural differentiation to be seen there. The data here show that the early specification of CB neural progenitors is not inhibited, and actually requires Nodal signaling for early specification (Fig. 3, Fig. S3). Our data agree with Yaguchi's conclusions, however, in that if Lefty is knocked down, its absence allows for both Nodal and for BMP to be overproduced (as BMP is activated by Nodal expression). The consequence is that there are many fewer differentiated neurons in the CB than if Nodal is overexpressed (which allows increased ectopic production of Lefty also) (Fig. S3). We conclude that Nodal is required for CB neural specification and differentiation and Lefty is necessary to exclude or limit Nodal concentrations from the CB as differentiation approaches.

The observed opposite effects of Nodal and BMP in different regions of neural specification is observed in other deuterostomes. In amphioxus, CNS formation requires Nodal signaling as well as inhibition of BMP signaling (Yu et al., 2007; Onai et al., 2010). The peripheral nervous system, by contrast, requires high levels of BMP4 signaling (Lu et al., 2012) indicating that TGFβ signaling differs in two domains of neural specification. In tunicates, Nodal is required for neural plate development, in the formation of the neural tube, and formation of motor neurons (Hudson and Yasuo, 2005; Mita and Fujiwara, 2007; Hudson et al., 2011; Navarrete and Levine, 2016). The peripheral nervous system, by contrast, is induced by FGF-Nodal and ADMP (BMP ligand) signaling (Pasini et al., 2006). Thus, the neurogenic ectoderm of the sea urchin appears to follow a common theme in which neurogenesis occurs at several sites using distinct patterning inputs. These conserved opposing signal inputs thus appear to have arisen early in deuterostome evolution as our data suggest that opposing Nodal-BMP signals operate in sea urchin neural specification as well.

Wnt signaling and neural specification

In vertebrates, anterior neural development requires inhibition of Wnt signaling, whereas posterior neurogenesis utilizes Wnt signaling (Logan and Nusse, 2004; Petersen and Reddien, 2009). The sea urchin also utilizes Wnt pathways to establish anterior-posterior identities (Angerer et al., 2011; Range et al., 2013). Because of this we asked how Wnt perturbations affected early neurogenesis. Wnt6 knockdowns affected all three domains of proneural development, albeit in different ways. Each proneural gene, with the exception of soxb1, was consistently absent in a large number of experiments in which Wnt6 was knocked down. At the same time, posterior delta expression consistently and dramatically increased in the Wnt6 knockdowns (Fig. S5). We suspect that the Wnt activity affecting delta occurs early in cleavage. qPCR data in Lytechinus variegatus showed that Wnt6 increases until the 60-cell stage of cleavage but then its expression largely disappears until gastrulation (Croce et al., 2011; Lhomond et al., 2012); thus, the knockdown of Wnt6 could have impacted early specification prior to neurogenesis, or, since its expression returns at gastrulation, at the time of neural specification, or both. Unfortunately, the MO perturbation approach cannot distinguish between these possibilities.

FGF signaling has an early impact on neural domains

Perturbation of FGF signaling with a pharmacological inhibitor (SU5402) decreases the number of soxC-expressing cells and fewer neurons differentiate (Garner et al., 2016). FGF signaling has long been known to induce and shape neural development across the animal kingdom (Lamb and Harland, 1995; Doniach, 1995; Mayor et al., 1997; Ericson et al., 1998; Wilson et al., 2001; Delaune et al., 2005; Matus et al., 2007; Stolfi et al., 2011; Navarrete and Levine, 2016). When examined in stem cell experiments, addition of FGF to cell cultures contributes to trajectories toward neural differentiation (Sterneckert et al., 2010; Cohen et al., 2010; Gouti et al., 2014). Fig. 4 confirms these earlier findings and shows that FGF impacts each of the three regions, and in each domain it impacts expression of sip1, delta and soxb1. Nevertheless, specification of the three domains is otherwise different, as summarized and modeled in Fig. 6, in that knockdown of FGF signaling does not uniformly affect the proneural specifiers.

Specification of neural precursor cells

We conclude that the three neural domains are impacted differently by signals that establish the initial territorial patterning. The question remains open as to whether the major impact of each signal is indirect by patterning the domain in which the neural progenitors later originate, or whether the impact directly affects specification in those cells as they initiate trajectories toward a neural fate. Likely it is a mixture of both. Nodal signaling, for example, begins hours prior to the first evidence of proneural gene expression. This suggests that Nodal is more likely to be involved in setting up territories in which neural specification later occurs, than in directly activating proneural genes. Only cis-regulatory analysis of those early neural genes will provide a definitive answer to that question. The patterning could be more complex than reflected here as well. For example, a cis-regulatory analysis of the Nodal gene showed Soxb1-binding sites to be involved in activation of nodal expression (Range et al., 2007), so the order of specification of neural cells could be complex.

Once the proneural genes are activated, their specification activity operates differently in the three domains. Fig. 6 demonstrates those differences in models based on the perturbation experiments. The ‘In common’ model (Fig. 6) shows that only a limited number of connections are in common to all three domains. This indicates that proneural specification in the three domains already differs substantially by the time of the Delta restriction. We conclude that there is not a uniform induction of neural development and that each domain of early specification must be treated independently in order to understand the trajectory of nervous system development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Embryo culture

Adult Lytechinus variegatus were obtained from the Duke University Marine Laboratory (Beaufort, NC, USA) or collected commercially by KP Aquatics LLC (Tavernier, Florida, USA) or Reeftopia (Florida Keys, USA). Gametes were obtained by 0.5 M KCl injection and embryos were cultured in artificial sea water at 23°C.

Transplantation of blastomeres

For the lineage analysis, single cells were transplanted from a donor embryo to the equivalent site in a host embryo. Donor embryos were labeled by injection of an RFP-expressing mRNA. The donor and host embryos were grown in filtered sea water until the 60-cell stage. They were transferred to calcium-free sea water and then to a Kiehart chamber. A single blastomere from the donor embryo was pulled into a suction pipette, then an identical blastomere was removed from the host embryo. The host blastomere was expelled and behind it the donor blastomere was inserted into the open site. In this way, the donor blastomere retained its original apical-basal orientation.

PCR amplification and cloning

RNA isolated from whole embryos at the mid-gastrula stage was used as a template for cDNA synthesis with the SMARTer PCR system (Clontech, 634925). A set of 5′ and 3′ nested PCR primers were designed for soxC based on alignment with the predicted soxC gene from the Strongylocentrotus purpuratus genome and other taxa. Primers for amplifying 1299 bp of the 5′ end of the cDNA were 5′-TGAAAGCAGCCAATCTGAGTCTATGAG-3′ followed by 5′-GACTTCCATTGCTCCCGACCGAATCAAGCG-3′. For the 3′ end, primers resulted in a 534-bp soxC fragment and were 5′-GCTCACGCCGCCCGCTAAAG-3′, then 5′-CCCGACTGGCTCCAACACG-3′. PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, A1360), sequenced, and used to design forward and reverse primers to produce a single full-length soxC fragment (5′-CGACTCACTATAGGGCAAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTAC-3′ and 5′-TTTGCAAAATGTTCAGGAAAATATAAATAATGTTCAGCTCTTTAGTTGTATGCTGAAATC-3′, respectively). Resulting PCR products were 1364 nucleotides in length and were cloned into pGEM-T easy vector. For preparation of an antisense RNA probe, soxC was linearized with SalI and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase (Roche, 10881767001).

Lv_INSM was cloned using PCR primers (forward, 5′-ACGTCTGCAATATGCCTCGAAACTTTCT-3′; reverse, 5′-AGAGTAGGCATTTGTAGGAGGATCACCTGT-3′) for a partial 1740 bp fragment. All other genes used in this study have been published (Angerer et al., 2000; Bradham et al., 2009; Croce et al., 2011; Rottinger et al., 2008; Slota and McClay, 2018; Sweet et al., 2002; Yuh et al., 2005).

Microinjection of MOs and mRNAs

Synthetic mRNAs and MOs (Gene Tools) were injected at the following concentrations: bmp2/4-MO (0.5 mM) 5′-GACCCCAATGTGAGGTGGTAACCAT-3′; bmp2/4 mRNA (0.1 µg/µl); chordin-MO (0.5 mM) 5′-CGGCGTAAAGTGTGATGCGGTACAT-3′; delta-MO (0.3 mM) 5′-GTGCAGCCGATTCGTTATTCCTTT-3′; nodal-MO (0.3 mM) 5′-TGCATGGTTAAAAGTCCTTAGAGAT-3′; nodal mRNA (0.1 µg/µl); lefty MO (0.5 mM) 5′-CTGGAGCACCAAGTG-3′; sip1-MO (0.6 mM) 5′-AGCTTCTCCAAAATCATGCACACCA-3′; six3-MO (0.6 mM) 5′-ATGTTTCCGACTCCGTCCAAACCAT-3′; wnt6-MO (0.75 mM) 5′-AATTGCTATTCGTGTCCACTCCATC-3′; fgfa-MO (0.75 mM) 5′-AGAAGAACTACGAAGCATGAAACGC-3′; soxb1-MO (0.3 mM) 5′-CACACCCGGAGCAGACATTTTGGTC-3′.

The above MOs have been previously published and were one of two MOs that gave the same phenotype for each gene listed above. One of them was used for this project in each case. The soxC MOs were used for the first time in this project and were controlled in two ways: rescue of a MO knockdown by injection of an mRNA that contained sequences that were not recognized by the MO (soxC, Fig. S6), and injection of two MOs with the same phenotypic and molecular outcome [soxC-MO-1 (0.75 mM) 5′-GTAGGTTTTGAGGAACCATCTTGAA-3′; soxC MO-2 (0.75 mM) 5′-TTGAAATCTGCATTC-3′]. Start sites are underlined.

bmp2/4, nodal and soxC mRNAs were made with Ambion mMESSAGE mMACHINE.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) was performed following standard methods using Roche NBT/BCIP and digoxigenin (DIG)-11-UTP-labeled RNA probes. Fluorescent detection of DIG was achieved with the Cy3-Tyramide Signal Amplification System (Perkin Elmer). Double-label fluorescent WMISH was performed as described by Croce and McClay (2010), or as chromogenic double-label WMISH using Roche digoxigenin-11-UTP and fluorescein (Flu)-12-UTP and detected with the substrates Fast Red (Roche, 11496549001) and NBT/BCIP as specified by Lapraz et al. (2009). Hoechst 33342 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) nuclear staining was applied to double-label WMISH at a concentration of 1:2000. An RNA probe was made to RFP with primers forward 5′-ATCGATTCGAATTAAGGCCTCTCGAGCCT-3′ and reverse 5′-TCATTTTATGTTTCAGGTTCAGGGGGA-3′ using the membrane RFP-PCS2 construct as a template. A probe was transcribed using T7 RNA Polymerase by adding a T7 sequence to the 5′ end of the reverse primer. Double in situ hybridization was performed with DIG and Flu probes to SoxC and RFP, respectively, using CellMask (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C37608) as a counterstain.

Published in situ probes used included chordin (Bradham et al., 2009), delta (Sweet et al., 2002), nodal (Bradham and McClay, 2006) and soxb1 (Angerer et al., 2005). Additional probes to Lytechinus genes were foxQ2, sip1, soxC, six3, insm and brn124. These were obtained by PCR using primers to Lytechinus genes obtained from a published transcriptome (Israel et al., 2016), and the sequences authenticated.

Scoring of perturbations and experimental outcomes

To score the result of each perturbation, in situ hybridizations were performed on over 100 embryos. We first determined the relative percentage of embryos that demonstrated a similar phenotype. The experiments in this paper were outcomes in which more than 80% of the knockdowns had similar, if not identical, phenotypes in each of at least three different tests. Usually more than 90% had the same phenotype, but we employed a cut off of 80%. Several factors contributed to rejected experiments. If the batch of eggs was bad and injected controls failed to develop normally the entire experiment was rejected. If the batch was highly irregular in that some embryos developed normally but a high percentage of others did not (greater than 20%), the experiment was rejected. If a MO gave inconsistent results compared with other experiments the experiment was rejected. This occurred infrequently but when it occurred it happened near the beginning or the end of a season when eggs were less able to tolerate MOs. For the genes considered here, we conducted MO injections in many separate experiments after establishing the best concentration of MO to use.

For experiments in which the perturbation surpassed the 80% threshold, and most did, we recorded and imaged at least ten examples from each of those. There were minor differences in the experiments that were included – early proneural cells in a territory might have three labeled cells and others five in the same experiment, or one embryo might be slightly more advanced in gastrulation than another, etc. We made no attempt to differentiate between those. Furthermore, our experiments overlapped. That is, we performed multiple perturbations with multiple mixes of markers in each experiment so results could be compared with one another based on the same conditions and embryo physiology. Additionally, the concentrations of perturbed signals were tested, before conducting the experiments. As indicated above, for some of the tests there were well over ten different repeats when we were comparing outcomes of one transcription factor versus another as we wanted to compare experimental outcomes of multiple perturbations on transcription factors under the same experimental conditions. Finally, we fixed embryos at different times based on a concern that a perturbation might simply be a delayed expression. Based on these experiments, we were confident that the outcomes reported not only surpassed the 80% threshold but the outcome of different markers was based on appropriate comparisons with other marker outcomes. GRN models were constructed using BioTapestry (Longabaugh, et al., 2009).

Immunostaining

Embryos were fixed with freezing methanol, washed three times with PBST (PBS with 0.5% Tween 20), and blocked with 4% normal goat serum in PBST for 1 h. Primary antibodies were used at the following concentrations: NgCAM (1:50), serotonin (1:1000; Sigma, 5545), synaptotagmin B (1E11; 1:50) (Nakajima et al., 2004; Burke et al., 2006b), 295-CB marker (1:200) (Bradham et al., 2009) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The secondary antibodies covalently attached to Cy2, Cy3 or Cy5 (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; Cy2: 715-255-151; Cy3: 711-167-003; Cy5: 315-007-003) were incubated with embryos for 30 min at room temperature. A Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope was used to image antibody-stained embryos with z-stack at 2-µM intervals. Confocal stacks of 20-25 images were merged together using the LSM software and post-processed with Adobe Photoshop and ImageJ. Single sections were scored to determine co-expression of two markers in the same cell. Alternatively, embryos were imaged with a Zeiss Axioplan microscope at 20×.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the McClay laboratory for critical input.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: D.R.M., S.L.F.; Methodology: E.M.; Validation: D.R.M., E.M.; Formal analysis: D.R.M., E.M., S.L.F.; Investigation: D.R.M., E.M., S.L.F.; Resources: D.R.M., S.L.F.; Data curation: E.M.; Writing - original draft: D.R.M., S.L.F.; Writing - review & editing: D.R.M., S.L.F.; Visualization: D.R.M., E.M., S.L.F.; Supervision: D.R.M.; Project administration: D.R.M.; Funding acquisition: D.R.M.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (RO1 HD 14483 and PO1 HD 037105 to D.R.M.). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.167742.supplemental

References

- Angerer L. M. and Angerer R. C. (2003). Patterning the sea urchin embryo: gene regulatory networks, signaling pathways, and cellular interactions. Curr. Top Dev. Biol. 53, 159-198. 10.1016/S0070-2153(03)53005-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angerer L. M., Oleksyn D. W., Logan C. Y., McClay D. R., Dale L. and Angerer R. C. (2000). A BMP pathway regulates cell fate allocation along the sea urchin animal-vegetal embryonic axis. Development 127, 1105-1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angerer L. M., Newman L. A. and Angerer R. C. (2005). SoxB1 downregulation in vegetal lineages of sea urchin embryos is achieved by both transcriptional repression and selective protein turnover. Development 132, 999-1008. 10.1242/dev.01650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angerer L. M., Yaguchi S., Angerer R. C. and Burke R. D. (2011). The evolution of nervous system patterning: insights from sea urchin development. Development 138, 3613-3623. 10.1242/dev.058172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnone M. I., Rizzo F., Annunciata R., Cameron R. A., Peterson K. J. and Martinez P. (2006). Genetic organization and embryonic expression of the ParaHox genes in the sea urchin S. purpuratus: insights into the relationship between clustering and colinearity. Dev. Biol. 300, 63-73. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artavanis-Tsakonas S., Delidakis C. and Fehon R. G. (1991). The Notch locus and the cell biology of neuroblast segregation. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 7, 427-452. 10.1146/annurev.cb.07.110191.002235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsi J. C., Li E. and Davidson E. H. (2015). Geometric control of ciliated band regulatory states in the sea urchin embryo. Development 142, 953-961. 10.1242/dev.117986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgrove B. W. and Burke R. D. (1986). Development of serotonergic neurons in embryos of the sea urchin, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Dev. Growth Differ. 28, 569-574. 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1986.00569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradham C. A. and McClay D. R. (2006). p38 MAPK is essential for secondary axis specification and patterning in sea urchin embryos. Development 133, 21-32. 10.1242/dev.02160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradham C. A., Oikonomou C., Kühn A., Core A. B., Modell J. W., McClay D. R. and Poustka A. J. (2009). Chordin is required for neural but not axial development in sea urchin embryos. Dev. Biol. 328, 221-233. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredt D. S. and Snyder S. H. (1989). Nitric oxide mediates glutamate-linked enhancement of cGMP levels in the cerebellum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 9030-9033. 10.1073/pnas.86.22.9030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke R. D., Angerer L. M., Elphick M. R., Humphrey G. W., Yaguchi S., Kiyama T., Liang S., Mu X., Agca C., Klein W. H. et al. (2006a). A genomic view of the sea urchin nervous system. Dev. Biol. 300, 434-460. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke R. D., Osborne L., Wang D., Murabe N., Yaguchi S. and Nakajima Y. (2006b). Neuron-specific expression of a synaptotagmin gene in the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. J. Comp. Neurol. 496, 244-251. 10.1002/cne.20939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke R. D., Moller D. J., Krupke O. A. and Taylor V. J. (2014). Sea urchin neural development and the metazoan paradigm of neurogenesis. Genesis 52, 208-221. 10.1002/dvg.22750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Ortega J. A. (1993). Mechanisms of early neurogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Neurobiol. 24, 1305-1327. 10.1002/neu.480241005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C. and Ayyanathan K. (2013). Snail/Gfi-1 (SNAG) family zinc finger proteins in transcription regulation, chromatin dynamics, cell signaling, development, and disease. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 24, 123-131. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2012.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. A., Itsykson P. and Reubinoff B. E. (2010). The role of FGF-signaling in early neural specification of human embryonic stem cells. Dev. Biol. 340, 450-458. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.01.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce J. C. and McClay D. R. (2010). Dynamics of Delta/Notch signaling on endomesoderm segregation in the sea urchin embryo. Development 137, 83-91. 10.1242/dev.044149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce J., Range R., Wu S.-Y., Miranda E., Lhomond G., Peng J. C., Lepage T. and McClay D. R. (2011). Wnt6 activates endoderm in the sea urchin gene regulatory network. Development 138, 3297-3306. 10.1242/dev.058792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham D. and Casey E. S. (2014). Spatiotemporal development of the embryonic nervous system of Saccoglossus kowalevskii. Dev. Biol. 386, 252-263. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson E. H., Rast J. P., Oliveri P., Ransick A., Calestani C., Yuh C.-H., Minokawa T., Amore G., Hinman V., Arenas-Mena C. et al. (2002a). A genomic regulatory network for development. Science 295, 1669-1678. 10.1126/science.1069883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson E. H., Rast J. P., Oliveri P., Ransick A., Calestani C., Yuh C.-H., Minokawa T., Amore G., Hinman V., Arenas-Mena C. et al. (2002b). A provisional regulatory gene network for specification of endomesoderm in the sea urchin embryo. Dev. Biol. 246, 162-190. 10.1006/dbio.2002.0635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaune E., Lemaire P. and Kodjabachian L. (2005). Neural induction in Xenopus requires early FGF signalling in addition to BMP inhibition. Development 132, 299-310. 10.1242/dev.01582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bernardo M., Castagnetti S., Bellomonte D., Oliveri P., Melfi R., Palla F. and Spinelli G. (1999). Spatially restricted expression of PlOtp, a Paracentrotus lividus orthopedia-related homeobox gene, is correlated with oral ectodermal patterning and skeletal morphogenesis in late-cleavage sea urchin embryos. Development 126, 2171-2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doniach T. (1995). Basic FGF as an inducer of anteroposterior neural pattern. Cell 83, 1067-1070. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90133-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duboc V., Röttinger E., Besnardeau L. and Lepage T. (2004). Nodal and BMP2/4 signaling organizes the oral-aboral axis of the sea urchin embryo. Dev. Cell 6, 397-410. 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00056-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duboc V., Lapraz F., Besnardeau L. and Lepage T. (2008). Lefty acts as an essential modulator of Nodal activity during sea urchin oral-aboral axis formation. Dev. Biol. 320, 49-59. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duboc V., Lapraz F., Saudemont A., Bessodes N., Mekpoh F., Haillot E., Quirin M. and Lepage T. (2010). Nodal and BMP2/4 pattern the mesoderm and endoderm during development of the sea urchin embryo. Development 137, 223-235. 10.1242/dev.042531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan S. A., Manova K., Chen W. S., Hoodless P., Weinstein D. C., Bachvarova R. F. and Darnell J. E. Jr. (1994). Expression of transcription factor HNF-4 in the extraembryonic endoderm, gut, and nephrogenic tissue of the developing mouse embryo: HNF-4 is a marker for primary endoderm in the implanting blastocyst. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 7598-7602. 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson J., Norlin S., Jessell T. M. and Edlund T. (1998). Integrated FGF and BMP signaling controls the progression of progenitor cell differentiation and the emergence of pattern in the embryonic anterior pituitary. Development 125, 1005-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehon R. G., Johansen K., Rebay I. and Artavanistsakonas S. (1991). Complex cellular and subcellular regulation of notch expression during embryonic and imaginal development of drosophila-implications for notch function. J. Cell Biol. 113, 657-669. 10.1083/jcb.113.3.657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner S., Zysk I., Byrne G., Kramer M., Moller D., Taylor V. and Burke R. D. (2016). Neurogenesis in sea urchin embryos and the diversity of deuterostome neurogenic mechanisms. Development 143, 286-297. 10.1242/dev.124503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouti M., Tsakiridis A., Wymeersch F. J., Huang Y., Kleinjung J., Wilson V. and Briscoe J. (2014). In vitro generation of neuromesodermal progenitors reveals distinct roles for wnt signalling in the specification of spinal cord and paraxial mesoderm identity. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001937 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitzler P. and Simpson P. (1991). The choice of cell fate in the epidermis of Drosophila. Cell 64, 1083-1092. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90263-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hejnol A. and Martindale M. Q. (2009). Coordinated spatial and temporal expression of Hox genes during embryogenesis in the acoel Convolutriloba longifissura. BMC Biol. 7, 65 10.1186/1741-7007-7-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati-Brivanlou A. and Melton D. (1997). Vertebrate embryonic cells will become nerve cells unless told otherwise. Cell 88, 13-17. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81853-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrique D., Abranches E., Verrier L. and Storey K. G. (2015). Neuromesodermal progenitors and the making of the spinal cord. Development 142, 2864-2875. 10.1242/dev.119768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry J. Q., Martindale M. Q. and Boyer B. C. (2000). The unique developmental program of the acoel flatworm, Neochildia fusca. Dev. Biol. 220, 285-295. 10.1006/dbio.2000.9628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinman V. F. and Burke R. D. (2018). Embryonic neurogenesis in echinoderms. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. Dev. Biol. 7, e316 10.1002/wdev.316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard-Ashby M., Materna S. C., Brown C. T., Chen L., Cameron R. A. and Davidson E. H. (2006a). Identification and characterization of homeobox transcription factor genes in Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, and their expression in embryonic development. Dev. Biol. 300, 74-89. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard-Ashby M., Materna S. C., Brown C. T., Tu Q., Oliveri P., Cameron R. A. and Davidson E. H. (2006b). High regulatory gene use in sea urchin embryogenesis: Implications for bilaterian development and evolution. Dev. Biol. 300, 27-34. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson C. and Yasuo H. (2005). Patterning across the ascidian neural plate by lateral Nodal signalling sources. Development 132, 1199-1210. 10.1242/dev.01688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson C., Ba M., Rouviere C. and Yasuo H. (2011). Divergent mechanisms specify chordate motoneurons: evidence from ascidians. Development 138, 1643-1652. 10.1242/dev.055426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel J. W., Martik M. L., Byrne M., Raff E. C., Raff R. A., McClay D. R. and Wray G. A (2016). Comparative Developmental transcriptomics reveals rewiring of a highly conserved gene regulatory network during a major life history switch in the sea urchin genus Heliocidaris. PLoS Biol. 14, e1002391 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach S. L., Yu J.-K. and Holland N. D. (2009). The origin and migration of the earliest-developing sensory neurons in the peripheral nervous system of amphioxus. Evol. Dev. 11, 142-151. 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2009.00315.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katow H., Yaguchi S. and Kyozuka K. (2007). Serotonin stimulates [Ca2+]i elevation in ciliary ectodermal cells of echinoplutei through a serotonin receptor cell network in the blastocoel. J. Exp. Biol. 210, 403-412. 10.1242/jeb.02666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara A., Chien C.-B. and Dawid I. B. (2002). The homeobox gene mbx is involved in eye and tectum development. Dev. Biol. 248, 107-117. 10.1006/dbio.2002.0709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny A. P., Kozlowski D., Oleksyn D. W., Angerer L. M. and Angerer R. C. (1999). SpSoxB1, a maternally encoded transcription factor asymmetrically distributed among early sea urchin blastomeres. Development 126, 5473-5483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazaei M. R., Bunk E. C., Hillje A.-L., Jahn H. M., Riegler E. M., Knoblich J. A., Young P. and Schwamborn J. C. (2011). The E3-ubiquitin ligase TRIM2 regulates neuronal polarization. J. Neurochem. 117, 29-37. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06971.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimelman D. (2016). Tales of tails (and Trunks): forming the posterior body in vertebrate embryos. Curr. Top Dev. Biol. 116, 517-536. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb T. M. and Harland R. M. (1995). Fibroblast growth factor is a direct neural inducer, which combined with noggin generates anterior-posterior neural pattern. Development 121, 3627-3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapraz F., Besnardeau L. and Lepage T. (2009). Patterning of the dorsal-ventral axis in echinoderms: insights into the evolution of the BMP-chordin signaling network. PLos Biol. 7, e1000248 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layden M. J., Boekhout M. and Martindale M. Q. (2012). Nematostella vectensis achaete-scute homolog NvashA regulates embryonic ectodermal neurogenesis and represents an ancient component of the metazoan neural specification pathway. Development 139, 1013-1022. 10.1242/dev.073221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Kim M., Kim N., Macfarlan T., Pfaff S. L., Mastick G. S. and Song M.-R. (2015). Slit and Semaphorin signaling governed by Islet transcription factors positions motor neuron somata within the neural tube. Exp. Neurol. 269, 17-27. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lhomond G., McClay D. R., Gache C. and Croce J. C. (2012). Frizzled1/2/7 signaling directs beta-catenin nuclearisation and initiates endoderm specification in macromeres during sea urchin embryogenesis. Development 139, 816-825. 10.1242/dev.072215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan C. Y. and Nusse R. (2004). The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 781-810. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh W. J., Davidson E. H. and Bolouri H. (2009). Visualization, documentation, analysis, and communication of large-scale gene regulatory networks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1789, 363-374. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T.-M., Luo Y.-J. and Yu J.-K. (2012). BMP and Delta/Notch signaling control the development of amphioxus epidermal sensory neurons: insights into the evolution of the peripheral sensory system. Development 139, 2020-2030. 10.1242/dev.073833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Durán J. M., Pang K., Børve A., Lê H. S., Furu A., Cannon J. T., Jondelius U. and Hejnol A. (2018). Convergent evolution of bilaterian nerve cords. Nature 553, 45-50. 10.1038/nature25030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Materna S. C., Howard-Ashby M., Gray R. F. and Davidson E. H. (2006). The C2H2 zinc finger genes of Strongylocentrotus purpuratus and their expression in embryonic development. Dev. Biol. 300, 108-120. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matus D. Q., Thomsen G. H. and Martindale M. Q. (2007). FGF signaling in gastrulation and neural development in Nematostella vectensis, an anthozoan cnidarian. Dev. Genes Evol. 217, 137-148. 10.1007/s00427-006-0122-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor R., Guerrero N. and Martinez C. (1997). Role of FGF and noggin in neural crest induction. Dev. Biol. 189, 1-12. 10.1006/dbio.1997.8634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellott D. O., Thisdelle J. and Burke R. D. (2017). Notch signaling patterns neurogenic ectoderm and regulates the asymmetric division of neural progenitors in sea urchin embryos. Development 144, 3602-3611. 10.1242/dev.151720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mita K. and Fujiwara S. (2007). Nodal regulates neural tube formation in the Ciona intestinalis embryo. Dev. Genes Evol. 217, 593-601. 10.1007/s00427-007-0168-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa A., Fujiyoshi Y. and Unwin N. (2003). Structure and gating mechanism of the acetylcholine receptor pore. Nature 423, 949-955. 10.1038/nature01748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses K., Ellis M. C. and Rubin G. M. (1989). The glass gene encodes a zinc-finger protein required by Drosophila photoreceptor cells. Nature 340, 531-536. 10.1038/340531a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y., Kaneko H., Murray G. and Burke R. D. (2004). Divergent patterns of neural development in larval echinoids and asteroids. Evol. Dev. 6, 95-104. 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2004.04011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi N., Renfer E., Technau U. and Rentzsch F. (2012). Nervous systems of the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis are generated by ectoderm and endoderm and shaped by distinct mechanisms. Development 139, 347-357. 10.1242/dev.071902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete I. A. and Levine M. (2016). Nodal and FGF coordinate ascidian neural tube morphogenesis. Development 143, 4665-4675. 10.1242/dev.144733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onai T., Yu J.-K., Blitz I. L., Cho K. W. and Holland L. Z. (2010). Opposing Nodal/Vg1 and BMP signals mediate axial patterning in embryos of the basal chordate amphioxus. Dev. Biol. 344, 377-389. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasini A., Amiel A., Rothbächer U., Roure A., Lemaire P. and Darras S. (2006). Formation of the ascidian epidermal sensory neurons: insights into the origin of the chordate peripheral nervous system. PLoS Biol. 4, e225 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patruno M., Thorndyke M. C., Candia Carnevali M. D., Bonasoro F. and Beesley P. W. (2001). Growth factors, heat-shock proteins and regeneration in echinoderms. J. Exp. Biol. 204, 843-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen C. P. and Reddien P. W. (2009). Wnt signaling and the polarity of the primary body axis. Cell 139, 1056-1068. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignoni F., Hu B., Zavitz K. H., Xiao J., Garrity P. A. and Zipursky S. L. (1997). The eye-specification proteins So and Eya form a complex and regulate multiple steps in Drosophila eye development. Cell 91, 881-891. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80480-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado V. F., Martins-Silva C., de Castro B. M., Lima R. F., Barros D. M., Amaral E., Ramsey A. J., Sotnikova T. D., Ramirez M. R., Kim H. G. et al. (2006). Mice deficient for the vesicular acetylcholine transporter are myasthenic and have deficits in object and social recognition. Neuron 51, 601-612. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Range R. C. and Wei Z. (2016). An anterior signaling center patterns and sizes the anterior neuroectoderm of the sea urchin embryo. Development 143, 1523-1533. 10.1242/dev.128165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Range R., Lapraz F., Quirin M., Marro S., Besnardeau L. and Lepage T. (2007). Cis-regulatory analysis of nodal and maternal control of dorsal-ventral axis formation by Univin, a TGF-beta related to Vg1. Development 134, 3649-3664. 10.1242/dev.007799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Range R. C., Angerer R. C. and Angerer L. M. (2013). Integration of canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling pathways patterns the neuroectoderm along the anterior-posterior axis of sea urchin embryos. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001467 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen S. L. K., Holland L. Z., Schubert M., Beaster-Jones L. and Holland N. D. (2007). Amphioxus AmphiDelta: evolution of Delta protein structure, segmentation, and neurogenesis. Genesis 45, 113-122. 10.1002/dvg.20278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo F., Fernandez-Serra M., Squarzoni P., Archimandritis A. and Arnone M. I. (2006). Identification and developmental expression of the ets gene family in the sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus). Dev. Biol. 300, 35-48. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottinger E., Saudemont A., Duboc V., Besnardeau L., McClay D. and Lepage T. (2008). FGF signals guide migration of mesenchymal cells, control skeletal morphogenesis and regulate gastrulation during sea urchin development. Development 135, 353-365. 10.1242/dev.014282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saudemont A., Haillot E., Mekpoh F., Bessodes N., Quirin M., Lapraz F., Duboc V., Rottinger E., Range R., Oisel A. et al. (2010). Ancestral regulatory circuits governing ectoderm patterning downstream of Nodal and BMP2/4 revealed by gene regulatory network analysis in an echinoderm. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001259 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini T., Kennedy T. E., Galko M. J., Mirzayan C., Jessell T. M. and Tessier-Lavigne M. (1994). The netrins define a family of axon outgrowth-promoting proteins homologous to C. elegans UNC-6. Cell 78, 409-424. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90420-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng G., dos Reis M. and Stern C. D. (2003). Churchill, a zinc finger transcriptional activator, regulates the transition between gastrulation and neurulation. Cell 115, 603-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood D. R. and McClay D. R. (1997). Identification and localization of a sea urchin Notch homologue: insights into vegetal plate regionalization and Notch receptor regulation. Development 124, 3363-3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood D. R. and McClay D. R. (1999). LvNotch signaling mediates secondary mesenchyme specification in the sea urchin embryo. Development 126, 1703-1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood D. R. and McClay D. R. (2001). LvNotch signaling plays a dual role in regulating the position of the ectoderm-endoderm boundary in the sea urchin embryo. Development 128, 2221-2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slota L. A. and McClay D. R. (2018). Identification of neural transcription factors required for the differentiation of three neuronal subtypes in the sea urchin embryo. Dev. Biol. 435, 138-149. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern C. D. (2005). Neural induction: old problem, new findings, yet more questions. Development 132, 2007-2021. 10.1242/dev.01794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern C. D. (2006). Neural induction: 10 years on since the ‘default model’. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 692-697. 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterneckert J., Stehling M., Bernemann C., Arauzo-Bravo M. J., Greber B., Gentile L., Ortmeier C., Sinn M., Wu G. and Ruau D., et al. (2010). Neural induction intermediates exhibit distinct roles of Fgf signaling. Stem Cells 28, 1772-1781. 10.1002/stem.498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolfi A., Wagner E., Taliaferro J. M., Chou S. and Levine M. (2011). Neural tube patterning by Ephrin, FGF and Notch signaling relays. Development 138, 5429-5439. 10.1242/dev.072108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolfi A., Ryan K., Meinertzhagen I. A. and Christiaen L. (2015). Migratory neuronal progenitors arise from the neural plate borders in tunicates. Nature 527, 371-374. 10.1038/nature15758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathmann R. R. (2007). Time and extent of ciliary response to particles in a non-filtering feeding mechanism. Biol. Bull 212, 93-103. 10.2307/25066587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Nadal-Vicens M., Misono S., Lin M. Z., Zubiaga A., Hua X., Fan G. and Greenberg M. E. (2001). Neurogenin promotes neurogenesis and inhibits glial differentiation by independent mechanisms. Cell 104, 365-376. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00224-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet H. C., Gehring M. and Ettensohn C. A. (2002). LvDelta is a mesoderm-inducing signal in the sea urchin embryo and can endow blastomeres with organizer-like properties. Development 129, 1945-1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii M., Matsuzaki F., Osumi N., Kaibuchi K., Nakamura S., Casarosa S., Guillemot F. and Nakafuku M. (1999). Transcription factors Mash-1 and Prox-1 delineate early steps in differentiation of neural stem cells in the developing central nervous system. Development 126, 443-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsakiridis A., Huang Y., Blin G., Skylaki S., Wymeersch F., Osorno R., Economou C., Karagianni E., Zhao S., Lowell S. et al. (2014). Distinct Wnt-driven primitive streak-like populations reflect in vivo lineage precursors. Development 141, 1209-1221. 10.1242/dev.101014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]