Abstract

IN BRIEF In 2017, 30 million Americans had diabetes, and 84 million had prediabetes. In this article, the authors focus on the journey people at risk for type 2 diabetes take when they become fully engaged in an evidence-based type 2 diabetes prevention program. They highlight potential drop-off points along the journey, using behavioral economics theory to provide possible reasons for most of the drop-off points, and propose solutions to move people toward making healthy decisions.

In 2017, ∼30 million Americans had diabetes. The total estimated direct and indirect costs of diagnosed diabetes in the United States was estimated at $327 billion (1). In addition, 84 million Americans had prediabetes, a condition in which blood glucose levels are higher than normal but not high enough for a diabetes diagnosis (2). Prediabetes is reversible, and, if addressed properly, type 2 diabetes can be prevented or delayed (3). Therefore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) emphasizes the importance of ensuring that people have appropriate knowledge, are screened or tested for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes, and, if appropriate, are directed to evidence-based prevention or treatment options.

There are scientific and practice-based approaches to disseminating knowledge, conducting screening and testing, and referring and offering options for chronic disease prevention and management (4–8), including for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes (8). However, almost 90% of people with prediabetes are unaware of their condition, making type 2 diabetes prevention a challenge (3).

Evidence-based interventions for preventing, delaying, or managing type 2 diabetes largely focus on long-term, achievable behavior changes (9–15). Such lifestyle changes may seem overwhelming to individuals for many reasons, including what some call an “obesogenic environment” in which consumers are surrounded by external stimuli making healthy choices difficult (16).

Meeting people where they are in their decision-making process may increase our ability to reduce the burden resulting from prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. This, in part, may involve shaping decision points so that healthier lifestyle alternatives become a thoughtful deliberative decision, stand out from the noise, are easier to choose, or feel less costly in terms of time, emotional commitment, or risk. Understanding the journey that individuals travel toward preventing type 2 diabetes can help public health professionals improve our effectiveness in reaching and engaging people at risk for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes.

In this article, we describe a consumer journey map that we developed to visualize pathways people must take to become fully engaged in an evidence-based type 2 diabetes prevention program. We also include alternative pathways because these represent possible points for redirection intervention. We highlight many aspects of the journey to type 2 diabetes prevention from increasing awareness of risk status to enrolling in a lifestyle change program. Understanding this journey may provide a clearer picture of solutions needed to move consumers toward type 2 diabetes prevention. We highlight points at which consumers may drop off the journey, use behavioral economics theory to provide possible explanations for these drop-off points, and offer solutions that health care providers (HCPs), health systems, and others may use to help guide consumers to make healthy lifestyle changes.

Type 2 Diabetes Prevention Journey

The effectiveness of lifestyle change approaches (through dietary change and increased physical activity) in reducing type 2 diabetes risk, primarily through weight loss, has been well documented (10–15). In addition, researchers and public health officials have considered how best to serve people based on their predicted risk level for developing type 2 diabetes within a 10-year period (17). Albright and Gregg (17) proposed a four-tiered risk stratification approach to type 2 diabetes prevention based on cost-effectiveness analyses and broader population health opportunities for intervention. Those at greatest risk (10-year type 2 diabetes risk of 30–40%) are expected to benefit most from an evidence-based lifestyle change program (LCP) that can be implemented in community-based and clinical settings, as well as through digital technology.

In 2010, the CDC established the National Diabetes Prevention Program (National DPP) to create and support the conditions necessary for provision of an evidence-based LCP (17–19). Although other approaches to type 2 diabetes prevention exist, including prescribing the drug metformin, research indicates that the LCP evaluated in the Diabetes Prevention Program research study is more effective in promoting weight loss than metformin therapy (5.6 and 2.1 kg weight loss, respectively) (11), leads to lower cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes over time (58 and 31% incidence rate reductions, respectively) (11–13), and can be effectively delivered by lay educators and clinical professionals (20).

Thus, our consumer journey uses the National DPP LCP as a focal point. Through the National DPP, consumers participate in a year-long LCP. The program is driven by a CDC-approved curriculum, includes a lifestyle coach that facilitates at least 22 sessions throughout the year, and typically takes place in an in-person group setting, although use of virtual programs is increasing (21).

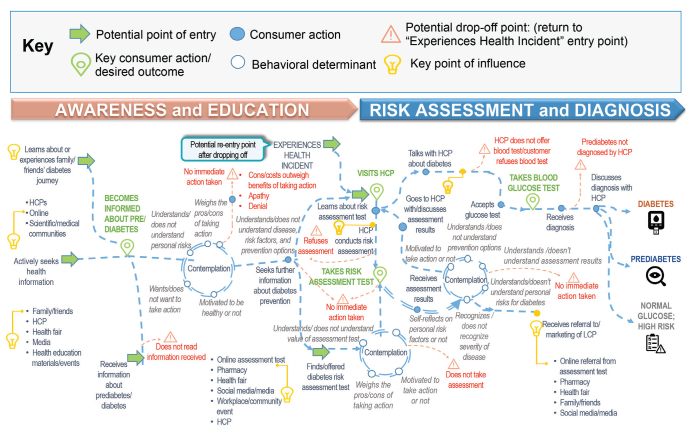

To increase the number of people who are aware of their type 2 diabetes status and to understand where we can intervene to guide people at high risk for type 2 diabetes or with prediabetes into an evidence-based prevention program such as the National DPP, we need to understand the process people go through as they learn about their risk and get a diagnosis and, ideally, what motivates them to initiate change. Our journey map helps us “see” the consumer experience from awareness/education about prediabetes and type 2 diabetes to prevention through assessment of risk, diagnosis, and enrollment in the National DPP LCP (Figures 1 and 2). To improve recruitment, we were particularly interested in understanding points at which consumers were at high risk for dropping off the journey.

FIGURE 1.

Diabetes: pre-diagnosis consumer journey.

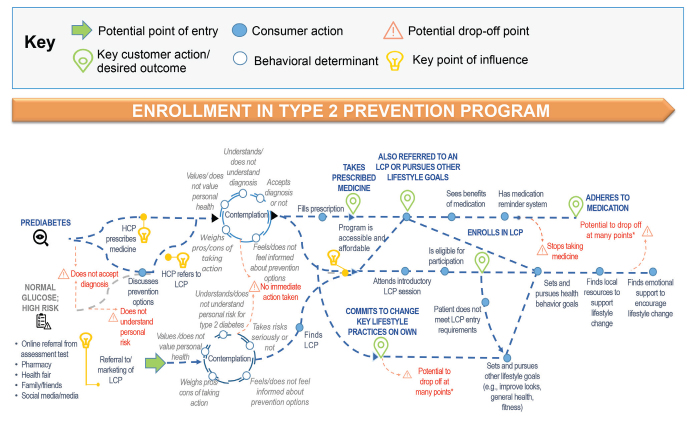

FIGURE 2.

Prediabetes enrollment phase.

Our type 2 diabetes consumer journey contains six key components, each of which offers cues or opportunities for application of a behavioral economics lens. The six components are 1) potential point of entry to the journey, 2) behavioral determinants, 3) small consumer actions, 4) key consumer actions/desired outcomes, 5) key points of influence, and 6) potential drop-off points. Points of entry are represented by green arrows in Figures 1 and 2 and are most likely influenced through public and private communication channels. Behavioral determinants are represented by clear circles at contemplation points.

Throughout the consumer journey, there are opportunities for contemplation that must occur before action is taken. Contemplation may include iterative thinking. This may be rapid or take time. In many cases, it may not happen consciously, with the consumer choosing an easy or comfortable option that may not be rational. Contemplation may include understanding (or not understanding) the information, risks, value, or options presented to them and performing a cost/benefit analysis; it will also include personalization or recognition of the individual’s status and, finally, decision-making.

In the journey map, small consumer actions are represented by blue circles, and key consumer actions are represented by inverted green tear drops. Small actions are necessary actions in the journey that may be missed but may also be facilitated by small interventions. Key actions are those that will likely define how the journey progresses.

Light bulbs represent key points of stakeholder influence. At these points, consumer-targeted interventions may be useful, but advancement to the next stage of the journey may also require intervention with one or more stakeholders.

Potential drop-off points are represented by red triangles. It is at these drop-off points where simple consumer-focused solutions may move the consumer further along their journey toward a healthier lifestyle.

The journey map has three major sections: awareness and education, risk assessment and diagnosis, and enrollment in a National DPP LCP. Prediabetes has no symptoms. (22) Therefore, the journey likely begins with awareness and education (sharing of information). The goal of this stage is to instill an awareness of type 2 diabetes risk, which may include a diagnosis of prediabetes. Consumers enter this stage in many different ways; we focus on three: learning about or receiving information through a family or friend, seeking health information based on general interest, or receiving information from an HCP, a health fair, or media exposure. In many cases, information from an HCP may include a direct diagnosis from test results obtained during a routine physical examination. Consumers may ignore the information or not feel a sense of urgency to act on this information and re-enter the awareness stage at a later time. This is the first potential drop-off point in the journey. Ideally, consumers will respond by accepting the information, reaching the first desired outcome in the journey (becoming informed), and enter a state of contemplating next steps.

The next goal in the journey is consumer engagement in a risk assessment. Formal risk assessment involves a blood test, typically performed by an HCP. However, the CDC, the American Diabetes Association, and other organizations provide question-based risk tests to give consumers an evidence-based indicator of their type 2 diabetes risk. Question-based risk tests often include recommendations to see an HCP, who can then diagnose prediabetes through a blood test. However, a consumer may engage in prevention activities motivated by a risk test alone, using information found outside of a health care system.

At this stage of the journey, some consumers will be diagnosed with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes, some will have glucose levels in the normal range but still be at risk for other reasons, and some will not be at risk. The consumer journey then becomes more complex, with greater need and opportunity to interact with health care and community-based systems and HCPs, as well as greater need for contemplation and repeated action. There are also more opportunities for dropping off and more action needed to successfully prevent type 2 diabetes.

If consumers are determined to be at risk for type 2 diabetes or are diagnosed with prediabetes, they should move toward prevention options. The most likely paths are depicted in Figure 2. For consumers with a diagnosis of prediabetes, the desired action is to engage in the evidence-based LCP offered through the National DPP. At the consumer level, there may be barriers to gaining access to this program, including a lack of knowledge about the program, lack of local availability, technology barriers (in the case of virtual offerings), and cost. A full discussion of these barriers is beyond the scope of this article. However, consumers may also interact with HCPs who recommend another approach, such as prescribing a drug such as metformin or recommending self-directed dietary change and physical activity.

The Challenge

When viewed in its entirety, the consumer journey gives us a sense of why interventions that address single barriers (e.g., lack of transportation) or more complex interventions (e.g., mass media campaigns) have only been partially successful in supporting consumers through their journey to the National DPP or to any intervention that requires multiple action points and sustained engagement. Consumers will face many internal and external challenges that a single-focus intervention may not address. Enrolling and participating in a program is a multi-stage process that may involve multiple small system or behavior changes throughout consumers’ ecosystems. Although most consumers will not be vulnerable to all drop-off points, the ecosystem should have safeguards in place to prevent predictable drop-offs.

Beyond the Consumer, But in the Journey

The journey described above and depicted in Figures 1 and 2 involves a range of stakeholders in addition to consumers, including HCPs, payors, program or intervention providers, health systems, family and community members, policymakers, employers (workplaces), and community-based partners. Although a full display and description of these journeys is beyond the scope of this article, we provide in Table 1 lists of the basic roles these stakeholders play at each stage in the journey. Below, we describe a brief example at the health care system/HCP level that may affect consumer awareness, education, and assessment for prediabetes.

TABLE 1.

Ecosystem Stakeholder Roles in Consumer Journey

| Awareness and Education | Risk Assessment and Diagnosis | Enrollment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCP | • Asks about family history | • Assesses/screens for long-term risks for developing diabetes | • Educates on prevention options and the importance of healthy lifestyle for preventing type 2 diabetes |

| • Asks about health behaviors | • Discusses risk assessment results and consumer’s risk for diabetes | • Gives consumer LCP referral | |

| • Explains impact of healthy behaviors and health status | • Orders and conducts blood glucose test | • Informs LCP that consumer was referred | |

| • Measures consumer’s BMI | • Educates on implications of diagnosis | • Refers to other resources | |

| • Encourages consumer to share diagnosis/genetic predisposition with family | • Assesses comorbidities and complications | • Prescribes necessary medication | |

| • Considers health literacy | • Assesses potential barriers to and facilitators of action | • Fills necessary prescription | |

| • Collects current medical status and medical history | • Refers to necessary LCP or HCPs | • Follows up on referrals to LCP or other HCPs | |

| • Assesses potential barriers to acting in a healthy way | • Follows up with consumer | ||

| • Considers insurance | |||

| • Follows up with consumer | |||

| Health Care System | • Ensures that intake forms include type 2 diabetes risk assessment | • Coordinates and shares information across HCP groups | • Acknowledges National DPP |

| • Offers information on prediabetes and diabetes across health clinics | • Clarifies treatment guidelines | • Offers electronic health record system that flags diabetes risk factors and prompts HCPs to offer blood glucose test | |

| • Develops clinical quality measures for prediabetes and diabetes | • Accepts new patients | • Clarifies treatment guidelines | |

| • Accepts health insurance | • Develops guidance for staff to educate patients on diagnoses | ||

| • Uses patient-generated health data | • Develops referrals and connections across clinics | ||

| • Refers to necessary LCP or HCPs | • Informs consumer of referral | ||

| CDC | • National DPP | • National DPP | • National DPP |

| • Promotes DPP | • Develops risk assessment | • Develops partnerships with organizations and program providers | |

| • Research and surveillance | Promotes risk assessment | Increases program referrals | |

| Clarifies processes and assumptions in patient care | Updates risk assessment | Provides program technical assistance | |

| Researches risk factors | Institutionalizes risk assessment | Expands reimbursement and cost coverage resources | |

| Provides care guidelines | Improves cost-effectiveness | Develops marketing mechanisms | |

| Conducts disease research | Provides navigation assistance for consumer referrals | Improves cost-effectiveness | |

| Develops health information tools | •Research and surveillance | Identifies and develops best practices for enrollment and retention | |

| Establishes health literacy guidelines | Clarifies patient care processes | Offers list of DPP classes, including locations and times | |

| Identifies best practices for prevention | Standardizes care guidelines | • Research and surveillance | |

| • Education | Develops reporting mechanisms and standards | Develops care and program quality measures | |

| Raises awareness of type 1 and type 2 diabetes and prediabetes | Expands outreach/screening | Clarify processes and assumptions in patient care | |

| Clarifies diagnosis standards | |||

| Payor | • Covers/subsidizes prevention tools | • Covers/subsidizes health care acquisition | • Covers/subsidizes program costs |

| • Incentivizes preventive behaviors | • Covers/subsidizes risk test/ screening | ||

| Family/Community | • Shares personal stories/family history of diabetes | • Encourages screening and blood glucose testing | • Helps consumer understand/ process test results |

| • Creates informal support groups to encourage healthy behavior options | • Shares information on where/how to get a type 2 diabetes risk assessment | • Shares personal stories and support for the newly diagnosed consumer | |

| • Shares health education/information materials | • Supports community members in identifying risks and fears | • Talks through information and questions for HCP | |

| • Works with HCP organizations to develop health education materials | • Encourages consumer to act | • Encourages participation in DPP or other LCP | |

| • Shares personal stories | • Shares information on resources to support lifestyle change | ||

| • Encourages consumer to visit HCP with risk assessment results | • Monitors/stays alert for any changes in diet, activity, or mental status of consumer | ||

| • Provides referral to HCPs | • Encourages healthy lifestyle | ||

| Policymaker | • Manages data collection, warehousing, analysis, and reporting | • Standardizes guidelines and reporting requirements | • Manages data collection, warehousing, analysis, and reporting |

| • Develops information-sharing guidelines | • Monitors insurance provision | • Develops, standardizes, and manages guidelines and reporting requirements | |

| • Ensures that risk assessment has accurate content | • Monitors insurance provision | ||

| Workplace | • Supports health screenings | • Offers incentives or health screenings | • Offers insurance that covers DPP |

| • Provides health education materials | • Holds information sessions on prevention options | • Brings in health educators to discuss diagnoses/answer questions | |

| • Offers healthy food and physical activity opportunities | • Has HCPs available for consultation | • Allows fitness breaks for employees | |

| • Offers effective insurance provision | • Hosts DPP in the workspace | ||

| • Offers formal or informal support groups or office hours | |||

| • Creates smoke-free environments | |||

| Community Partner | • Supports health screenings | • Offers incentives or health screenings | • Helps consumer enroll and participate in the DPP |

| • Provides health education materials | • Offers DPP classes | ||

| • Offers healthy food and physical activity opportunities | • Provides case management/ navigation while consumer is enrolled in the DPP | ||

| • Creates smoke-free environments | • Provides financial assistance for medications as needed |

When we consider the consumer journey and interventions targeting it, we generally assume that a health care system is available, with the knowledge and support to meet consumer needs. Although the National DPP, an evidence-based solution to preventing prediabetes, is available, little is known about whether health care systems and HCPs are prepared to address prediabetes. In one study of 155 primary care providers, only 6% correctly identified prediabetes risk factors, and only 17% were able to identify appropriate prediabetes fasting glucose and A1C parameters (23). In addition, the term prediabetes may be used differently by different HCPs (24).

Those with appropriate knowledge of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes must also have knowledge and awareness of and trust in prevention options. Tseng et al. (23) reported that, for management of prediabetes, behavioral weight loss programs were selected by only 11% of primary care providers as a recommended action for their patients.

HCPs may benefit from having clinical decision support and program locator tools integrated into their work flows to reduce their burden of facilitating the consumer journey (25,26). This integration covers the most basic connections needed between health care systems, HCPs, and consumers. Interventions focusing solely on consumers without considering the limitations of health care systems and HCPs may have less-than-optimal results, not because of consumers dropping off, but rather because of knowledge and awareness gaps at the system or HCP level.

Developing Solutions Using a Behavioral Economics Lens

Many health interventions focus on addressing tangible barriers to support consumers through their journey, such as making programs more accessible by providing transportation, child care, or tailored information (27–29). Behavioral economics–informed solutions may be much smaller and address subtler, less tangible challenges associated with potential drop-off points during these contemplation states.

Behavioral economics considers the effects of psychological, social, cognitive, and emotional factors on the decisions individuals make. This feature is in contrast to conventional economic theory, which assumes that individuals make decisions as if they were making rational choices to maximize a set of preferences (27–31). Interventions that use a behavioral economics lens look at ways in which human behavior can depart from rational-actor models and aim to mitigate the effects of cognitive biases or other inconsistences.

Key principles of behavioral economics are used to develop interventions or solutions that “nudge” people to make a decision or complete a small action (28,30–32). Matheson et al. (33) argue that provision of “specific and deliberate steps” is needed to resolve challenges leading to chronic disease. Wood and Neal (34) argue that, to create a new habit, three types of interventions must be offered in tandem: those that encourage behavior repetition, those that create stable context cues, and those that are given in an uncertain way or at random intervals (such as slot machines). We agree with these approaches but suggest that multi-component approaches, addressing challenges at multiple points with multiple stakeholders along the journey, may be more effective. Multiple behavioral economics–informed solutions can also be used in combination to drive consumers toward mindset change and, if repeated over time and in combination, can lead to the habit formation necessary for type 2 diabetes prevention efforts to be effective.

Evidence for use of behavioral economics for long-term change, particularly for health behaviors, is sparse, although conceptual models have been proposed (35). In addition, it may be unclear who should be nudged, when they should be nudged, and how they should be nudged. In Table 2, we provide examples of how a behavioral economics lens can help answer these questions. From the consumer journey described in Figures 1 and 2, we draw from the stages and drop-off points (barriers). From the behavioral economics literature, we use 12 concepts (availability bias, salience, limited attention, learned helplessness, “ostriching,” overconfidence, self-categorization, social influence, identity, loss-aversion, present bias, and scarcity) related to the identified barriers and provide solutions that fit the nudge concept of behavioral economics (and in most cases are low in cost and scalable) (36). Finally, we name the stakeholders in the consumers’ ecology who would implement the solutions (acknowledging that, in some cases, the solutions, such as building in reminders, can be applied to stakeholders as well).

TABLE 2.

How Behavioral Economics Can Explain and Facilitate Consumers’ Enrollment in the National DPP’s LCP

| Awareness and Education (become aware of type 2 diabetes risk and decide to change behavior) | Risk Assessment and Diagnosis (discover a National DPP LCP and are receptive to information about it) | Enrollment (decide the program is a good fit now and enroll in an upcoming class) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers (drop-off points) | Do not feel an urgent need to act | Misperceive type 2 diabetes risk and ability to change it | Lack social influence | Do not feel an urgent need to act | Misperceive type 2 diabetes risk and ability to change it | Lack social influence | Misperceive that commitment costs outweigh program’s future benefits | Lack social influence | Misperceive that commitment costs outweigh program’s future benefits |

| Behavioral economic concepts | Availability bias,* salience,† limited attention‡ | Learned helplessness,§ ostriching,|| overconfidence,¶ self-categorization# | Social influence,** identity†† | Availability bias,* salience,† limited attention‡ | Learned helplessness,§ ostriching,|| overconfidence,¶ self-categorization# | Social influence,** identity†† | Loss-aversion,‡‡ present bias,§§ scarcity|||| | Social influence,** identity†† | Loss-aversion,‡‡ present bias,§§ scarcity|||| |

| Possible solutions | Planning prompts, promotion materials providing clear and actionable next steps, personalized promotion materials, built-in reminders, use of word-of-mouth referrals, physician referrals, provision of salient examples of success | Use of word-of-mouth referrals, provision of program details from a trusted source, provision of salient examples of success, continued support by referrer, opportunities for mingling with program participants | Connecting participant with a lifestyle change coach, addressing questions about program details and costs, self-affirmation activities, opportunities for mingling with program participants | ||||||

| Stakeholder interventions (levels) | LCPs (Family and Community, HCP, Health Care System) | LCPs (Family and Community) | |||||||

Availability bias: propensity to overweigh the likelihood of an event happening based on how easily that event comes to mind.

Salience: the degree to which an item or choice stands out and captures our attention.

Limited attention: prevents us from weighing all options equally; thus, our choices become easily affected by which factors are most salient.

Learned helplessness: the belief that one has little control over a situation and that no action can improve or change an outcome.

Ostriching: “burying one’s head in the sand” when there is a possibility of bad news.

Overconfidence: being surer of one’s own beliefs, predictions, feelings, and abilities than an objective evaluation would warrant.

Self-categorization: people innately understand themselves and others through categorical distinctions placing themselves in an “in group” among others with similar characteristics.

Social influence: when people they feel close to and trust, like friends, family, community members, and doctors, instruct them to take action, they usually listen.

Identity: people act on the basis of different group identities, which shift and can become more or less prominent at different moments and in different contexts.

Loss-aversion: the tendency to overweigh losses relative to gains of the same magnitude.

Present bias: the idea that the impact of a choice or action we make or take now is really important.

Scarcity: having a chronic lack of resources, which leads individuals to focus their attention on immediate needs as opposed to long-term ones.

Select Solutions at Key Points in the Consumer Journey

To improve success at the awareness stage, behavioral economics solutions can be used to drive Web traffic to risk assessments, prediabetes information, and the National DPP. One option is to modify health cards that appear on many search engine pages when searching for common health terms such as prediabetes or type 2 diabetes. To increase discovery of a National DPP LCP, solutions may include adding links to facilitate action and including language to increase a sense of urgency or self-efficacy.

To help create a sense of urgency during the awareness stage, barriers created by ostriching (ignoring bad news) and uncertainty aversion (leading to avoiding decisions) can be addressed by optimizing recruitment material through personalization of content and integrating planning prompts and reminders. Changes such as these can help consumers see the value of enrolling at that moment instead of putting it off for later.

Using interventions that leverage social referrals, relying on friends and family or program champions, builds on the behavioral economics principles of social norms and social networks. Using social referrals may help address self-categorization, through which consumers mentally put themselves in the “in group” (those participating in lifestyle change) and avoid preferences or activities of an “out group.” The principle of social accountability, which posits that people are more likely to stick to their commitments and exhibit pro-social behavior when they know others are watching, may also come into play.

Health care systems and community-based programs may be able to leverage electronic health records to increase screening, testing, and referrals by HCPs and can use behavioral economics principles to optimize prediabetes risk tests and tools to facilitate finding an appropriate National DPP LCP. Finally, once a consumer has made a commitment to connect with a National DPP LCP, the program can offer an informational session that employs multiple nudges to shift the consumer mindset to enroll.

Incorporating solutions such as optimized recruitment material and information sessions can help participants learn that the benefits of completing the National DPP LCP far outweigh the commitment they must make, leading them to decide if the program is a good fit. An information session built on the principle of endowed progress, through which consumers persist in a process when they believe that they have already successfully taken at least one action toward their end goal, may lead to continued participation in that process. Other principles, such as mental contrasting (a visualization technique and problem-solving tool that strengthens goal pursuit by addressing perceived obstacles in advance), self-affirmation (reminding people about their past accomplishments to counteract their natural defensiveness or apathy) and self-disclosure (the voluntary action of telling others more detail about yourself) can inform activities within information sessions to further encourage enrollment.

Discussion

Encouraging people to participate in and maintain a healthy lifestyle to prevent chronic disease remains a public health challenge, as evidenced by the overall prevalence of chronic disease, and for some specific diseases, increasing incidence rates (37,38). Several challenges exist in informing, recruiting or referring, and enrolling consumers into an LCP and, ultimately, having consumers participate in and complete such an intervention and maintain a healthy lifestyle once it is over. This is often the case even when evidence-based interventions are available. Even pharmacological approaches, such as the use of metformin, are fraught with adherence challenges (39).

A successful approach, given the complexity and comprehensive nature of the barriers, should be multi-faceted. First, those seeking to intervene should try to understand the full journeys consumers will take and their potential drop-off points or barriers to a successful journey. Program implementers can then integrate their role and the role other stakeholders play in circumventing the barriers.

In the case of type 2 diabetes prevention, an evidence-based intervention exists. Although the journey is complex, CDC and others have proposed integrated approaches at the local, state, and national levels (37), and we have proposed using multiple nudge solutions at various levels in the consumer ecosystem to ensure that consumers successfully navigate this journey.

The growth in chronic disease, particularly in new cases of type 2 diabetes, warrants implementing evidence-based interventions to address this pressing health challenge. Doing so would lead to improvements in health, a reduction in type 2 diabetes incidence, and, ultimately, costs savings at both the individual and societal level resulting from increased productivity and lower medical costs.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank LaShonda Hulbert, Shawn Jawanda, Renee Skeete, Stephanie Rutledge, Erin Keyes, and Meklit B. Hailemeskal for reviewing the manuscript and participating in the creation of the consumer journey concept. Tara Earl participated in conceptualization of behavioral economics solutions to consumer drop-off points, and Shing Zhang and Nancy Silver created the visual representation of the consumer journey.

Duality of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions

R.E.S. wrote the manuscript and drafted the consumer journey. K.P., M.C.J., and A.L. reviewed/edited the manuscript and contributed to the development of Table 1 and the consumer journey. C.K., J.L., and M.D. reviewed/edited the manuscript and contributed to the development of Table 1. R.E.S. is the guarantor of this work and takes full responsibility for its content.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care 2018;41:917–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Diabetes Report Card 2017. Atlanta, Ga, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prediabetes. Available from www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/prediabetes.html. Accessed 5 April 2018

- 4.Task Force on Community Preventive Services Recommendations for client- and provider-directed interventions to increase breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening. Am J Prev Med 2008;35(Suppl. 1):S21–S25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Community Guide Increasing cancer screening: multicomponent interventions. Available from www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Cancer-Screening-Multicomponent-Interventions.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2018

- 6.The Community Guide Reducing tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure: mass-reach health communication interventions. Available from www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Tobacco-Mass-Reach-Health-Communication.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2018

- 7.The Community Guide Preventing birth defects: community-wide campaigns to promote the use of folic acid supplements. Available from www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Birth-Defects-Community-Wide-Promote-Folic-Acid.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2018

- 8.Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abnormal blood glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:861–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeh MC, Heo M, Suchday S, et al. . Translation of the Diabetes Prevention Program for diabetes risk reduction in Chinese immigrants in New York City. Diabet Med 2016;33:547–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. . The long‐term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20‐year follow‐up study. Lancet 2008;371:1783–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knowler WC, Barrett-Conner E, Fowler SE, et al. ; DPP Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346:393–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DPP Research Group; Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al. . 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet 2009;374:1677–1686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DPP Research Group Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3:866–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinhold KR, Miller CK, Marrero DG, Nagaraja HN, Focht BC, Gascon GM. A randomized controlled trial translating the Diabetes Prevention Program to a university worksite, Ohio, 2012–2014. Prev Chronic Dis 2015;12:E210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerrison G, Gillis RB, Jiwani SI, et al. . The effectiveness of lifestyle adaptation for the prevention of prediabetes in adults: a systematic review. J Diabetes Res 2017;2017:8493145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powell P, Spears K, Rebori M. What is obesogenic environment? Availble from. www.unce.unr.edu/publications/files/hn/2010/fs1011.pdf. Accessed 16 April 2018.

- 17.Albright AL, Gregg EW. Preventing type 2 diabetes in communities across the U.S: the National Diabetes Prevention Program. Am J Prev Med 2013;44(4 Suppl. 4):S346–S351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albright A. Prevention of type 2 diabetes requires BOTH intensive lifestyle interventions and population-wide approaches. Am J Manag Care 2015;21(Suppl. 7):S238–S239 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention What is the National DPP? Available from www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/about/index.html. Accessed 5 April 2018.

- 20.Ali MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui J, Williamson DF. How effective were lifestyle interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program? Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Lifestyle change program details. Available from www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/lifestyle-program/experience/index.html. Accessed 12 April 2018

- 22.The Mayo Clinic. Prediabetes: overview. Available from www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/prediabetes/symptoms-causes/syc-20355278. Accessed 12 April 2018

- 23.Tseng E, Greer RC, O’Rourke P, et al. . Survey of primary care providers’ knowledge of screening for, diagnosing and managing prediabetes. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:1172–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas JJ, Moring JC, Baker S, et al. . Do words matter? Health care providers’ use of the term prediabetes. Health Risk Soc 2017;19:5–6, 301–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical decision support. Available from www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/decision/clinical/index.html. Accessed 10 May 2018

- 26.Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practices using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ 2005;330:765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richburg-Hayes L, Anzelone C, Dechausay N, et al. . Behavioral Economics and Social Policy: Designing Innovative Solutions for Programs Supported by the Administration for Children and Families. OPRE Report No. 2014-16a. Washington, D.C., Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014. Available from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/bias_final_full_report_rev4_15_14.pdf. Accessed 12 April 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thaler R, Benartzi S. Save More Tomorrow™: using behavioral economics to increase employee saving. J Pol Econ 2004;112:S164–S187. Available from www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/380085. Accessed 12 April 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang LL, DeVore AD, Granger BB, Eapen ZJ, Ariely D, Hernandez AF. Leveraging behavioral economics to improve heart failure care and outcomes. Circulation 2017;136:765–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thaler R, Sustein C. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. London, U.K., Penguin Books, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thaler RH, Sunstein CR, Balz JP. Choice architecture. Available from papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1583509. Accessed 12 April 2018

- 32.The Behavioral Insights Team EAST: four simple ways to apply behavioral insights. Available from behaviouralinsights.co.uk/publications/east-four-simple-ways-apply-behavioural-insights. Accessed 12 April 2018

- 33.Matheson GO, Pacione C, Shultz RK, Klugl M. Leveraging human-centered design in chronic disease prevention. Am J Prev Med 2015;48:472–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wood W, Neal D. Healthy through habit: interventions for initiating and maintaining health behavior change. Behav Sci Pol 2016;2:71–83 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mogler BK, Shu SB, Fox CR, et al. . Using insights from behavioral economics and social psychology to help patients manage chronic diseases. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:711–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samson A. (Ed.). The Behavioral Economics Guide 2016. Available from http://www.behavioraleconomics.com. Accessed 12 April 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gatwood JD, Chisholm-Burns M, Davis R, et al. . Disparities in initial oral antidiabetic medication adherence among veterans with incident diabetes. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2018;24:379–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA, Bowman BA. Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of death and disability in the USA. Lancet 2014;384:45–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Leading causes of death and numbers of deaths, by sex, race, and Hispanic origin: United States, 1980 and 2014. In Health, United States, 2015. Available from www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf#019. Accessed 10 May 2018 [Google Scholar]