Abstract

The processes of DNA replication and mitosis allow the genetic information of a cell to be copied and transferred reliably to its daughter cells. However, if DNA replication and cell division were always carried out in a symmetric manner, it would result in a cluster of tumor cells instead of a multicellular organism. Therefore, gaining a complete understanding of any complex living organism depends on learning how cells become different while faithfully maintaining the same genetic material. It is well recognized that the distinct epigenetic information contained in each cell type defines its unique gene expression program. Nevertheless, how epigenetic information contained in the parental cell is either maintained or changed in the daughter cells remains largely unknown. During the asymmetric cell division (ACD) of Drosophila male germline stem cells (GSCs), our previous work revealed that preexisting histones are selectively retained in the renewed stem cell daughter, whereas newly synthesized histones are enriched in the differentiating daughter cell. We also found that randomized inheritance of preexisting histones versus newly synthesized histones results in both stem cell loss and progenitor germ cell tumor phenotypes, suggesting that programmed histone inheritance is a key epigenetic player for cells to either remember or reset cell fates. Here we will discuss these findings in the context of current knowledge on DNA replication, polarized mitotic machinery, and ACD for both animal development and tissue homeostasis. We will also speculate on some potential mechanisms underlying asymmetric histone inheritance, which may be used in other biological events to achieve the asymmetric cell fates.

Keywords: stem cell, asymmetric cell division, histone, epigenetic inheritance

Introduction

Asymmetric inheritance of cell fate determinants in developing organisms is known to play a major role in cellular differentiation, and it is a fundamental process in generating cellular diversity. Our current understandings of the mechanisms that orchestrate ACD have been gathered from a wide variety of developmental model organisms, including yeast, flies, worms, and mice, among others. As early as 1905, cell lineage analysis of the ascidian Styela partita identified cytoplasmic determinants derived from the egg that segregate to distinct cell lineages responsible for generating five specialized tissue types (Conklin, 1905). Despite examples of intrinsic segregation of cell fate determinants, it was not until 1994 that the first determinant, Numb, was molecularly characterized (Rhyu et al., 1994). To date, key determinants of cell fate found to be distributed unequally in ACDs include cell surface receptors, transcription factors, mRNA, DNA, histones, and organelles such as endosomes, centrosomes, and mitochondria (Carmena, 2008; Katajisto et al., 2015; Knoblich, 2008; Tran et al., 2013). During development, this asymmetry is critical for generating divergent cell fates and progenitor cell self-renewal. Failure of these mechanisms can lead to severe defects in cell proliferation, which manifest as tissue degeneration or tumorigenesis.

The asymmetric inheritance of DNA molecules as a cell fate determinant during ACD has been considered previously. In 1975, John Cairns proposed the “immortal strand” hypothesis, suggesting that the stem cell continually inherits the old DNA strands to minimize accumulation of random DNA replication errors that could change cell fate (Cairns, 1975). However, the immortal strand hypothesis has not been widely accepted owing to the lack of solid supporting in vivo evidence. Two similar (and more accepted) models, named the “strand-specific imprinting and selective chromatid segregation” (Klar, 1994; Klar, 2007) and “silent sister chromatid” (Lansdorp, 2007) hypotheses suggest epigenetic differences between sister chromatids are required to direct the asymmetric outcomes during ACD.

In this review, we will discuss how the processes of DNA replication, chromosomal segregation, and cell division lead to asymmetric outcomes and how organisms are able to develop, maintain homeostasis, and adapt to a changing environment through these asymmetric processes. We argue that the symmetric outcome of making exact copies of DNA and daughter cells is necessary but not sufficient for the propagation and diversification of life. We then hypothesize that the development and homeostasis of multicellular organisms depend on modified molecular and cellular processes to generate asymmetry from the mechanisms that control the otherwise equal distribution of cellular components into the two daughter cells. We will discuss studies that have reported on asymmetric inheritance of cell fate determinants in diverse organisms with a focus on epigenetic differences between sister chromatids, as well as examples of nonrandom segregation of sister chromatids.

DNA replication is an asymmetric process that can be biased

The asymmetric outcomes of DNA replication and cell division rely heavily on modifications that lead to heritable changes in gene expression and, hence, cell fate, but without altering the primary sequence of the DNA, known as epigenetics (Jacobs and van Lohuizen, 2002; Probst et al., 2009; Ringrose and Paro, 2004; Turner, 2002). It is possible that DNA replication has a heretofore underappreciated role in establishing distinct epigenomes between sister chromatids that will be inherited by each daughter cell upon cell division. DNA consists of two antiparallel strands containing a deoxyribose sugar-phosphate backbone that supports varying sequences of four bases that pair in a complementary way. Through elegant studies, we know that DNA is synthesized in a semi-conservative manner, meaning that each daughter DNA will inherit one template strand and one newly synthesized strand as double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) (Meselson and Stahl, 1958).

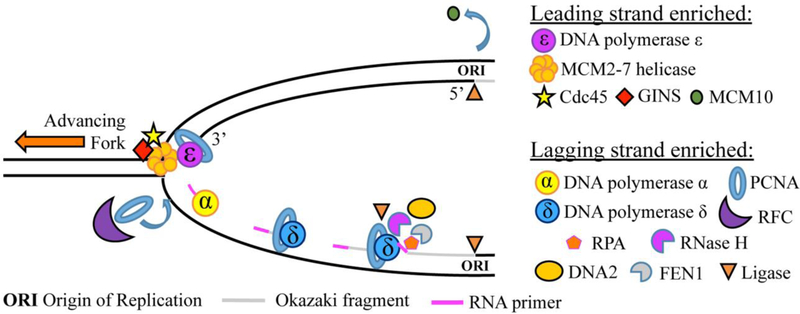

The components of DNA replication machinery bind to DNA in pairs and initiate DNA replication in a bidirectional manner. Because DNA can only be synthesized in the 5’→ 3’ direction, the DNA polymerase responsible for creating the new strand is required to read the single-stranded (ss) template in the 3’→ 5’ direction, beginning from an existing 3’−OH overhang. Interestingly, this creates an inherent asymmetry as to how the new strands are synthesized. One strand, the leading strand, begins with a single RNA primer and can be synthesized continuously as the advancing replication fork exposes more ss template and the template is read in the 3’→ 5’ direction (BESSMAN et al., 1956; BESSMAN et al., 1958; Kornberg et al., 1989; LEHMAN et al., 1958; Meselson and Stahl, 1958). However, the other template strand, termed the lagging strand, runs antiparallel to the leading strand and cannot be read by the polymerase in the same direction as the advancing replication fork. Thus, the lagging strand is synthesized in short segments, called Okazaki fragments, in the direction opposite to the advancing replication fork. Each Okazaki fragment begins with an RNA primer and is, in fact, synthesized by DNA polymerases different from those of the leading strand (Balakrishnan and Bambara, 2013; Okazaki et al., 1968; Sakabe and Okazaki, 1966). Furthermore, the lagging strand must undergo additional processing to remove ss ‘flaps’ left behind. To explain, polymerase δ displaces nucleotides from the previously synthesized polymerase α fragment, and nicks left between fragments must be sealed by DNA ligase (Bambara et al., 1997; Cerritelli and Crouch, 2009; Rossi et al., 2008) (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1:

Leading- versus lagging-strand-enriched molecules with their function in brief (Langston et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2014).

| Replication Component | Strand Enrichment | Function |

|---|---|---|

| DNA polymerase ε | Leading | Synthesizes leading strand |

| MCM2–7 helicase | Leading | Unwinds DNA for replication |

| Cdc45 | Leading | Interacts with Mcm proteins; converts the pre-replicative complex to the initiation complex |

| GINS | Leading | Essential for the interaction of Mcm proteins and Cdc45 during initiation and elongation |

| MCM10 | Leading | Activates the Cdc45-MCM-GINS helicase at DNA replication origins |

| DNA polymerase α | Lagging | Begins replication by synthesizing an RNA primer and adding ~20 DNA nucleotides |

| DNA polymerase δ | Lagging | Synthesizes the lagging strand |

| PCNA | Lagging | Ring-shaped clamp that stabilizes DNA polymerases onto DNA |

| RFC | Lagging | Loads PCNA onto the DNA |

| RPA | Lagging | Binds ssDNA to prevent secondary structure formation |

| RNase H | Lagging | Removes any remaining RNA nucleotides |

| DNA2 and FEN1 | Lagging | Remove ‘flaps’ of DNA created by DNA Pol δ, advancing into and lifting the previous Okazaki fragment |

| Ligase | Lagging | Seals nicks in the DNA backbone between segments of newly synthesized DNA |

Figure 1: A schematic cartoon of DNA replication fork.

DNA replication, while intended to create two equal copies of a double stranded DNA template, does possess inherent asymmetries relative to strand synthesis. Indeed, several experiments have demonstrated functional outcomes that arise from asymmetric leading versus lagging strand synthesis. For example, the discontinuous synthesis of the lagging strand has been postulated as a more error-prone process. This could potentially lead to an increased mutation rate that may be evolutionarily beneficial without compromising the genomic stability of the continuously synthesized leading strand (Furusawa, 2014). Additionally, it has been shown that molecular lesions created during lagging strand synthesis contribute to mating type switching in both the budding yeast S. cerevisiae and the fission yeast S. pombe (Hanson and Wolfe, 2017).

While much is known about fork licensing and elongation, it is interesting to consider that the origins of replication have yet to be well defined within most eukaryotes, and that transcription can have a direct effect on the localization of pre-replication complexes (Cayrou et al., 2011; Vashee et al., 2003). For each cell type, the transcriptional machinery may affect the density and location of replication origins, the length of the replicons in between them, and bias the replication of certain genes to either the leading or the lagging strand. Known fork-blocking proteins could also serve to bias the length and direction of replication forks. Paradoxically, while transcription may affect DNA replication, DNA replication is also likely to affect transcription. That is, transcription machinery is displaced as DNA is unwound and must rebind following fork passage. Now, however, it can only bind one of the two copies of DNA present after replication. Studies have shown that rebinding of the transcription machinery can be biased to either the leading or the lagging strand, depending on the rate of fork progression and the inherent maturation of the two strands after fork passage (Alabert and Groth, 2012; Vasseur et al., 2016). It has also been shown that this biased rebinding event can lead to heritable changes in gene expression where one daughter cell ‘remembers’ its transcriptional state and the other daughter cell lags behind, with the need to re-establish its transcriptional state (Ferraro et al., 2016).

Histone recycling after DNA replication could bias cell fate

In addition to the inherent asymmetries between the leading and lagging strands of DNA replication, one must also consider asymmetries in the epigenetic modification of the DNA itself, as well as the nucleosome, the basic packaging unit of DNA. Methylation of DNA has been well studied and is generally associated with transcriptional repression. Just as with the transcriptional machinery, recovery of DNA methylation appears more slowly on the lagging strand than it does on the leading strand, perhaps allowing time for the two sisters to be differentially recognized or for the methylome on the lagging strand to be re-written (Stancheva et al., 1999; Tajbakhsh and Gonzalez, 2009).

Another major epigenetic information carrier for cell fate is the nucleosome structure, which is comprised of eight histone proteins (two H2A-H2B dimers and one H3-H4 tetramer). Posttranslational modifications of histone proteins have profound effects on cell fate and transcriptional activity (Peterson and Laniel, 2004). Of note, nucleosomes must be disassembled ahead of the replication fork and reassembled onto one of the two new dsDNA templates that now exist in the wake of the fork (McKnight and Miller, 1977; Sogo et al., 1986). While the process of new histone deposition onto the DNA has been well studied, how preexisting histones are recycled during DNA replication is less clear (Burgess and Zhang, 2013). Elucidating this mechanism is essential to understanding how DNA replication may impact epigenetic information partitioning.

To date, three possible models of histone recycling after fork progression have been proposed. First, the semiconservative model suggests that the H3-H4 tetramer is split into two dimers such that the four dimers of the nucleosome (two H2A-H2B and two H3-H4) are evenly distributed between the two new dsDNA strands. This mechanism was thought to be an elegant solution to evenly distributing epigenetic information such that both daughter strands would inherit equal posttranslational histone modifications, predominantly carried by the H3 and H4 tails (Zhu and Reinberg, 2011). However, several lines of evidence have surfaced against the semiconservative model of histone recycling. For example, it has been found that the H3-H4 tetramer rarely, if ever, splits into two dimers once the tetramer has been assembled (Xu et al., 2010). Furthermore, the tails of H3 and H4 within each tetramer are not symmetrically modified (Chen et al., 2011; van Rossum et al., 2012; Voigt et al., 2012). Thus, even if the tetramer does split, with each new dsDNA inheriting one H3-H4 dimer, then the epigenetic information of the previously unreplicated region would not be preserved equally between the two daughter strands (Figure 2A). Second, the dispersive model of histone recycling proposes that the H3-H4 tetramer remains intact, but the tetramers and dimers disassembled ahead of the fork are still randomly distributed between the leading and lagging strands behind the fork (Alabert et al., 2015; Alabert and Groth, 2012; Hammond et al., 2017; Herz et al., 2014; Jackson and Chalkley, 1981; Jackson and Chalkley, 1985). Additionally, histone modifying enzymes use the posttranslational modifications present on these recycled tetramers to appropriately modify the new H3-H4 tetramers that become incorporated nearby (Alabert et al., 2015; Alabert and Groth, 2012; Audergon et al., 2015; Ayyanathan et al., 2003; Hansen et al., 2008; Margueron et al., 2009; Ragunathan et al., 2015) (Figure 2B). Third, the conservative model of histone recycling suggests that preexisting H3-H4 tetramers can be biased to incorporate nonrandomly into either the leading or the lagging strand (Leffak et al., 1977; Riley and Weintraub, 1979; Roufa and Marchionni, 1982; Seale, 1976; Seidman et al., 1979; Weintraub, 1976). Such mechanism could provide one daughter strand with the same epigenetic information as that in the mother cell, whereas the other daughter strand could predominantly incorporate new, unmarked histones devoid of such epigenetic information (Figure 2C).

Figure 2: Models of histone recycling and the epigenetic effect of each.

(A) Semi-conservative model. The semiconservative model suggests that the H3-H4 tetramer is split into two dimers that are evenly distributed between the two new dsDNA daughters. While a potentially elegant solution to evenly distributing relevant epigenetic information between the two new daughter strands, it has been shown that the H3-H4 tetramer rarely, if ever, splits and the tails of H3 and H4 within each tetramer are not symmetrically modified (Chen et al., 2011; van Rossum et al., 2012; Voigt et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2010). Thus, the epigenetic information of that previously unreplicated region would not be preserved equally onto the two daughter strands. (B) Dispersive model. The dispersive model of histone recycling proposes that the H3-H4 tetramer remains intact, but the tetramers and dimers disassembled ahead of the fork are still randomly distributed onto the leading and lagging strands behind the fork (Alabert et al., 2015; Alabert and Groth, 2012; Hammond et al., 2017; Herz et al., 2014; Jackson and Chalkley, 1981; Jackson and Chalkley, 1985). Additionally, histone modifying enzymes use the posttranslational modifications present on these recycled tetramers to appropriately modify the new H3-H4 tetramers that become incorporated nearby and the epigenome of the mother strand is retained in both daughter strands (Alabert et al., 2015; Alabert and Groth, 2012; Audergon et al., 2015; Ayyanathan et al., 2003; Hansen et al., 2008; Margueron et al., 2009; Ragunathan et al., 2015). (C) Conservative model. The conservative model of histone recycling suggests that preexisting H3-H4 tetramers can be biased to incorporate nonrandomly into either the leading or the lagging strand (Leffak et al., 1977; Riley and Weintraub, 1979; Roufa and Marchionni, 1982; Seale, 1976; Seidman et al., 1979; Weintraub, 1976). Such a mechanism could provide one daughter strand with the same epigenetic information as that in the mother cell whereas the other daughter strand predominantly incorporates new, unmarked histones devoid of such epigenetic information.

Strong evidence supports both the dispersive model and the conservative model of histone recycling during DNA replication. Of note, these studies have been done in various organisms and cell types, as well as in vitro. It is important to consider that histone recycling may be different during DNA replication, depending on the biological context. For example, how stem cells maintain their stemness through many rounds of mitosis has been a long-standing question in the epigenetics field. Our finding that preexisting histones are selectively retained in the renewed stem cell daughter, whereas newly synthesized histones are enriched in the differentiating daughter cell in Drosophila male GSCs suggests that the predominant mechanism of histone recycling may be the conservative model (Snedeker et al., 2017; Tran et al., 2013; Tran et al., 2012; Xie et al., 2015; Xie et al., 2017). Our finding also indicates that the asymmetric epigenome established during DNA replication needs to be recognized and properly segregated by potentially polarized mitotic machinery. Next, we will discuss how chromatin-bound cis-factors and non-chromatin-bound trans-regulators coordinate to ensure nonrandom sister chromatid segregation.

The centromere: an epigenetic basis to distinguish asymmetric sister chromatids

Centromeres direct chromosome segregation during mitosis, which is mediated by the recruitment of the kinetochore as well as microtubules. Centromeres are epigenetically defined in most eukaryotes by a centromere-specific histone H3 variant known as centromere identifier (CID) in flies and CENP-A in mammals (Allshire and Karpen, 2008; Palmer et al., 1987). The centromeric histones have undergone rapid evolution and the length of DNA defined as the centromeric region has greatly increased through a positive selection process termed “centromere-drive” (Henikoff et al., 2001; Henikoff and Malik, 2002; Malik, 2009). An expansion of the centromeric DNA by recombination could create a centromere that has increased microtubule binding ability, which could, in turn, lead to preferential chromosome transmission, such as that found during female meiosis. For example, the mouse karyotype typically consists of 2n = 40 telocentric chromosomes, but numerous natural populations show dramatically reduced chromosome numbers where 2n = 22 chromosomes, a phenomenon attributed to Robertsonian (Rb) fusion, a chromosomal rearrangement that joins two telocentric chromosomes to create one metacentric chromosome (White et al., 2010). Retention of a metacentric chromosome in offspring depends on the direction of chromosome segregation during meiosis I (MI). The direction of chromosome segregation depends on centromere strength; stronger centromeres have more CENP-A protein and outer kinetochore components, and, hence, higher microtubule binding ability. Therefore, the stronger centromeres are preferentially retained in the egg, whereas the weaker centromeres are preferentially segregated in the polar body during meiosis (Figure 3) (Chmatal et al., 2014). A similar event has also been reported in budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae where the inner and outer kinetochore components show asymmetric segregation in a lineage-specific manner during meiosis (Thorpe et al., 2009).

Figure 3: The “centromere drive” hypothesis holds that centromere strength directs chromosome segregation in meiosis I.

When two telocentric chromosomes fuse in a natural population to create one metacentric chromosome: (A) if telocentric chromosome fusion creates a metacentric chromosome with a stronger centromere, then the metacentric chromosomes preferentially segregate to the egg in MI. (B) If telocentric chromosome fusion creates a metacentric chromosome with a weaker centromere, then 40% of the metacentric chromosomes segregate to the polar body in MI (Chmatal et al., 2014).

However, this phenomenon has not been reported during mitosis. Therefore, it would be worth testing a hypothesis similar to “centromere-drive” during ACD. Because two distinct daughter cells arise from ACD, it is plausible that epigenetic asymmetry on sister chromatids would include sister centromeres. This would allow the mitotic machinery to distinguish the sister chromatids.

Chromatin organization: a mechanism for trans-nuclear membrane communication

Chromosomes contain euchromatic and heterochromatic domains, which have distinct nuclear functions and organization throughout development (Mekhail and Moazed, 2010; Misteli, 2007; Rajapakse and Groudine, 2011). The most striking examples of chromatin organization are the centromere cluster (Rabl configuration), heterochromatin cluster (chromocenter), and telomere cluster (bouquet configuration) at the nuclear periphery (Fang and Spector, 2005; Fransz et al., 2002; Funabiki et al., 1993; Guenatri et al., 2004; Jin et al., 1998; Scherthan and Schonborn, 2001; Zickler, 2006; Zickler and Kleckner, 1998). The centromere cluster and the pericentromeric heterochromatin region could provide a location where specific factors are concentrated to facilitate communication between chromosomes and microtubules. For example, kinetochore proteins and heterochromatin factors, such as HP1 and H3K9me2/3 could concentrate at the centromere or pericentromeric regions (Bernard et al., 2001; Kawashima et al., 2007). Interestingly, mutations of kinetochore components Mis6 and Nuf2 (NDC80 complex) result in centromere declustering (Appelgren et al., 2003; Asakawa et al., 2005). Nevertheless, how kinetochore components are linked to the nuclear envelope and mediate centromere dynamics remain elusive.

Mitotic hallmarks, such as H3S10P, H3T3/T6P, H3.1/2S28P, and H1.4S26P, are shown to be predominantly associated with old histones at early mitosis in cultured human cell lines (Lin et al., 2016). We wanted to define the mechanism(s) by which sister chromatids might be recognized and segregated in an asymmetric manner. To begin to address this question, we recently reported that the H3T3P mark at pericentromeric regions distinguishes old and new histones in Drosophila male GSCs (Xie et al., 2015). Furthermore, misregulation of this phosphorylation leads to randomized inheritance of old and new H3, as well as both GSC loss and progenitor germ cell tumor phenotypes. This suggests that asymmetric phosphorylation of H3T3 at the pericentromeric regions may be one mechanism by which the mitotic machinery can recognize and faithfully segregate asymmetric sister chromatids (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Pericentromeric heterochromatin modifications could regulate centromere and microtubule interactions, as well as nonrandom sister chromatid segregation.

(A) Sequential phosphorylation of T3 on old histone H3 before new H3 at the pericentromeric region during mitosis in Drosophila male GSCs ensures nonrandom sister chromatid segregation. (B) Expression of H3T3A, where T3 of histone H3 is mutated to Alanine (A), randomizes the segregation pattern of sister chromatids (Xie et al., 2015; Xie et al., 2017).

Centrosomes and Microtubules: mechanical tools for nonrandom sister chromatid segregation

The centrosome is a complex molecular structure that functions as the major microtubule-organizing center in the cell. Recent studies have revealed intriguing asymmetry between mother and daughter centrosomes, as well as the involvement of such asymmetry in a number of critical cellular processes. Two centrosomes are distinct from each other, partly resulting from their microtubule nucleation activity and their age differences. Interestingly, the older of the two centrosomes has been shown to nucleate microtubules considerably earlier, which is correlated with a differential response to signaling molecules (Anderson and Stearns, 2009; Pelletier and Yamashita, 2012; Rebollo et al., 2007; Rusan and Peifer, 2007) (Figure 5). The observation that centrosome age could be associated with differential response to various signaling cues has raised the possibility that the inherent asymmetry of centrosomes could contribute to the determination of distinct cell fates during ACD.

Figure 5: Nonrandom segregation of sister chromatids, asymmetric centrosome inheritance, and asymmetric histone inheritance during Drosophila male GSC ACD.

Asymmetric GSC divisions give rise to two daughter cells: a self-renewed GSC that remains in proximity to the niche (blue hub cells), and a differentiating daughter cell that migrates to the distal side of the cell, resulting from a perpendicular spindle orientation relative to the niche. During this division, mother (green) and daughter (orange) centrosomes are asymmetrically inherited by the self-renewed GSC and the differentiating daughter cell, respectively. Nonrandom sister chromatid segregation of the X/Y sex chromosomes was demonstrated in male GSCs utilizing CO-FISH (Chromosome Orientation Fluorescence in situ Hybridization) in combination with strand-specific probes to distinguish sister chromatids. Sex chromosomes (purple and blue outlined chromatids) exhibit an approximate 85:15 bias segregation during male GSC cell division. A dual-color labeling strategy to distinguish preexisting (green) versus newly synthesized (red) canonical histone H3 revealed that old histone H3 is selectively retained in the self-renewed GSC (green nuclei), whereas newly synthesized H3 is enriched in the differentiating daughter cell (red nuclei).

In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe during meiosis, LINC (linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton) connects the centrosome with telomeres (Tomita and Cooper, 2007), whereas during mitosis LINC connects the centrosome with centromere, rather than telomeres (Fernandez-Alvarez et al., 2016). Loss of such contacts during meiosis or mitosis abolishes normal spindle formation (Fennell et al., 2015; Tomita et al., 2013), suggesting that the trans-nuclear envelope contacts through LINC play an important role in mediating crosstalk between centrosomes and chromosomes, residing in the cytoplasm and the nucleus, respectively.

Studies have revealed that the Drosophila male GSCs and mouse neural glial progenitor cells inherit the mother centrosome (Wang et al., 2009; Yamashita et al., 2007), whereas Drosophila neuroblasts and female GSCs inherit the daughter centrosome (Conduit and Raff, 2010; Januschke et al., 2011). This difference in centrosome inheritance patterns during ACD provokes the speculation that the developmentally programmed centrosome located at the stem cell side, whether mother or daughter, might bear fate determinants or other characteristics that contribute to stem cell fate. Therefore, it is conceivable that early microtubule nucleation at one of the two centrosomes, either age-dependent or in differential response to signaling molecules, at the stem cell side could engage in crosstalk with centromeric chromatin though LINC to ensure preferential sister chromatid attachment.

In summary, a cohort of trans factors, such as centrosomes, microtubules, nuclear membrane, and kinetochore complex, and cis factors, such as centromeres and epigenetic modifications on chromatin, act together in differential recognition and nonrandom segregation of sister chromatids. In the future, more studies are needed to understand how this axis of asymmetry, centrosome −microtubule − nuclear membrane − kinetochore − centromere − chromatid, is regulated and whether disruption of this axis leads to any cellular defects.

Asymmetric inheritance of cell fate determinants in unicellular organisms

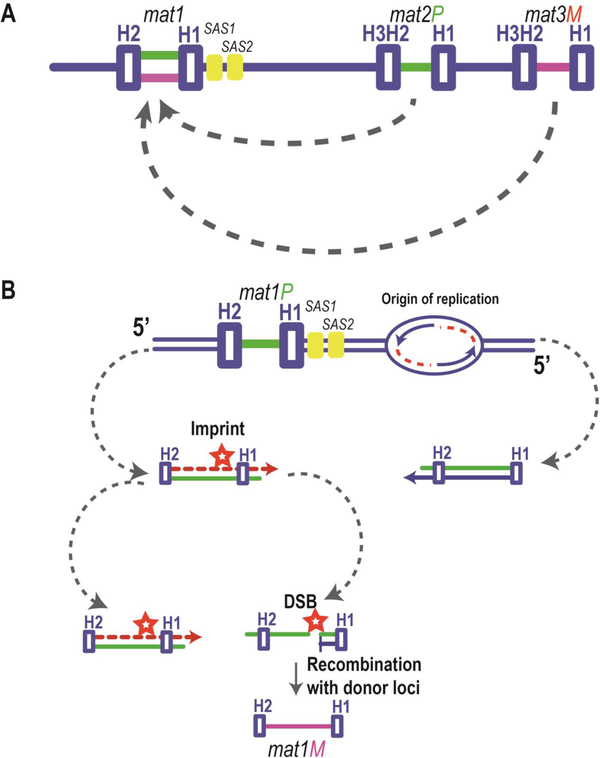

Over the past three decades, the mating type switching behavior in two eukaryotic yeasts, the budding yeast S. cerevisiae and the fission yeast S. pombe, has served as an exceptional model to dissect the mechanisms of asymmetric cell fate specification (Klar, 2007). Mating type switching is accomplished by two functionally similar but molecularly distinct, processes in S. cerevisiae and S. pombe. The genomes of these species encode a three-cassette gene structure containing one active and two silent copies of the mating type locus. These cells can alter their mating type through a programmed DNA rearrangement process and execute it through the cleavage of the active locus, while a copy of a silent locus serves as a donor for synthesis-dependent strand annealing (Dalgaard and Klar, 2001). In S. pombe, the mating type switching pattern results from the inheritance of a specific parental DNA strand, which is dependent upon a strand-specific epigenetic imprint that occurs during lagging strand DNA synthesis (Dalgaard and Klar, 2001). Generation of this imprinting phenomenon is dependent upon the orientation of DNA replication at the active mating type locus, mat1 (Dalgaard and Klar, 1999). Specifically, it is thought that one or two ribonucleotides form the imprint and that these RNA residues may have been originally used to prime DNA synthesis on the lagging strand, which may be ligated and not removed by the DNA repair machinery during the first S phase (Vengrova and Dalgaard, 2006). This imprint is then maintained until the next S phase, when the leading strand replication complex is stalled at the imprint locus (Vengrova and Dalgaard, 2004) (Figure 6). This stalled fork induces a recombination event between mat1 and one of the two silent donor cassettes, mat2P or mat2M, leading to mating type switching. As a result of this mechanism, one of the two daughters of a newly switched cell inherits a switch in mating locus, and one of the four granddaughters has the switched mating type. Together, these findings demonstrate that asymmetries inherent in DNA replication can be developmentally regulated to ensure distinct cell fate determination after cell division. Considering that S. pombe is a haploid organism, it does not require selective segregation of sister chromatids; instead, the daughter cell inherits the cell fate epigenetic determinant from the chromosome randomly from the parental cell. For such mechanism to function reliably in a diploid organism, selective recognition of the distinct chromatid would be necessary.

Figure 6: Mating type switching in S. pombe.

(A) Arrangement of the mating type region, displaying switchable mat1 and silent donor loci mat2P and mat3M. The mat1 locus contains either plus (green coding) or negative (purple coding) regions derived from the donor cassettes, mat2P (plus information) or mat3M (minus information). Homology domains H1, H2, and H3 are annotated. Arrows indicate recombination events leading to mating type switching. SAS1 and SAS2 are cis-acting sequences involved in imprinting. (B) Generation of the imprint is regulated by the direction of mat1 DNA replication. The imprint (shown as a red star) is installed if the specific strand is the lagging strand (designated by the dashed red line). During the next S-phase, when the leading strand (designated by the blue arrow) replication complex encounters the imprint, a double-strand break (DSB) occurs. The broken strand then utilizes one of the two the donor loci, either mat2P or mat3M, as a template to repair the mat1 locus.

Mating type gene switching in S. cerevisiae is mediated by an enzyme not found in S. pombe, the HO-endonuclease, which is responsible for the programmed creation of a site-specific double-strand break at the active mating type locus, MAT (Haber, 2012). Mating type DNA rearrangements occur exclusively in mother cells, not in the daughter cells or spores. The discovery of the exclusive expression of HO in the mother cells led to another breakthrough in asymmetric inheritance of cell fate determinants (Bobola et al., 1996; Long et al., 1997; Sil and Herskowitz, 1996). S. cerevisiae achieves mitotic proliferation through a highly polarized ACD, giving rise to a smaller daughter (bud) cell. After each ACD, the cell-fate determinant asymmetric synthesis of HO (Ash1) mRNA, encoding a HO-specific transcriptional repressor, is asymmetrically inherited by the bud cell (Long et al., 1997). This asymmetric localization is mediated by a ribonucleoprotein complex, which is transported across the actin cytoskeleton to the distal tip where translation of Ash1 mRNA occurs (Cosma, 2004). To date, more than 20 mRNAs have been found to be asymmetrically inherited during S. cerivisiae cell division (Jambhekar et al., 2005; Shepard et al., 2003).

Cell polarity and spindle orientation are coordinated prior to mitosis and mediated by three polarized cytoskeletal systems, including actin, septins, and microtubules (Bi and Park, 2012). Orientation of the yeast spindle pole body (SPB), the equivalent of the centrosome, is linked to a stereotypic pattern of SPB inheritance (Pereira and Yamashita, 2011). Spindle formation starts in the mother cell body with the older centrosome oriented towards the bud, which establishes spindle polarity, directing orientation of the mitotic spindle along the mother-bud axis and the inheritance of the old SPB by the daughter cell. A similar phenomenon is observed in the ACDs of the Drosophila male GSCs, as well as mouse neural glial progenitor cells, where the mother centrosome is preferentially retained near the hub-GSC interface and by the radial glial progenitors that remain in the ventricular zone, respectively (Wang et al., 2009; Yamashita et al., 2007). The molecular mechanisms that govern the establishment of this cell polarity and spindle orientation have been highly conserved throughout evolution (Pereira and Yamashita, 2011). This role in establishing polarity, as well as preferential asymmetric inheritance, raises the intriguing possibility that distinct centrosomes may be associated with recognizing and segregating cell fate determinants, such as individual chromatids, which has been previously suggested for adult stem cells, including Drosophila male GSCs and skeletal muscle satellite cells (Shinin et al., 2006; Xie et al., 2015).

ACD in Drosophila – A model of nonrandom segregation of sister chromatids and asymmetric epigenetic inheritance

Nonrandom segregation of sister chromatids occurring in the germline was uncovered by utilizing chromosome oriented fluorescence in situ hybridization (CO-FISH) to resolve individual chromatid inheritance (Yadlapalli and Yamashita, 2013). The CO-FISH method revealed that sex chromosomes (X and Y) exhibit an approximate 85:15 strand bias during male GSC ACD [e.g. 85% of GSCs inherit the Watson strand (W): 15% of GSCs inherit the Crick strand (C) at each GSC division]. Autosomes including both the 2nd and the 3rd chromosomes, however, display a random segregation pattern (50:50), but show a consistent co-segregation mode (i.e., WW:CC instead of WC:CW) (Figure 5). Of note, earlier studies using BrdU to test global DNA segregation demonstrated that male GSCs do not follow the immortal strand model (Yadlapalli and Yamashita, 2013). These results, combined with our work showing that H3T3P distinguishes old versus new histones in dividing GSCs, suggest that epigenetic differences that distinguish sister chromatids might coordinate selective chromatid segregation and direct cell fate after mitosis. Together, these findings reveal the presence of asymmetric epigenetic inheritance during cell division, which may maintain GSC cell identity, while concomitantly resetting the chromatin structure in the differentiating daughter cell to ensure proper cell fate specification.

Nonrandom segregation of DNA strands in mammalian cells and disease

Adult skeletal muscle in mammals has an extraordinary regenerative capacity after injury. The regenerative precursor cells originate from the satellite muscle cells, a tissue-specific adult stem cell population (Collins et al., 2005). Mononucleated satellite cells are mitotically quiescent and reside in a niche under the basal lamina, or basement membrane, juxtaposed to the muscle fiber. As skeletal muscle stem cells, satellite cells divide asymmetrically to maintain the stem cell population and differentiate, leading to new myofiber formation (Kuang et al., 2007) (Figure 7). Interestingly, the orientation of the cell division within the satellite cell niche determines cell fate (Kuang et al., 2007). Sister cells arising from a satellite cell division are found in a planar orientation where either both cells remain in direct contact with the basal lamina and myofiber, or in an apical-basal orientation where one daughter cell is pushed toward the basal lamina and the other is oriented apically toward the myofiber, occurring with 92% and 8% frequency, respectively. Further studies revealed that apical−basal orientation of cell divisions resulted in asymmetric cell fates. The daughter cell attached to the basal lamina remained a stem cell, whereas the daughter cell that loses contact with the basal lamina becomes a committed myogenic cell. In contrast, stem cell divisions in a planar orientation were symmetric and generated identical daughter cells.

Figure 7: Orientation of muscle satellite cell division determines cell fate.

(A) Satellite cells (blue) reside under the basal lamina adjacent to the myofibril (red). (B) Satellite cells enter either a symmetric cell division or an ACD. ACD, i.e., when the mitotic spindle is oriented perpendicular to the muscle fiber, generates a self-renewing (expressing Pax7+/Myf5-, blue cell) and a differentiating daughter cell (Pax7+/Myf5+, red cell). Symmetric divisions, i.e., when the mitotic spindle is oriented parallel to the muscle fiber, generate two self-renewing cells that are both Pax7+/Myf5-. (C) Co-segregation of template DNA strands labeled with BrdU (purple) and asymmetric distribution of Numb (green) to one daughter cell were observed in asymmetrically dividing myoblasts derived from satellite cells during anaphase in an 11:1 bias.

Satellite cells express the transcription factor Pax7, but not Myf5 (Pax7+/Myf5-), whereas the asymmetric differentiating daughter cell expresses both Pax7 and Myf5 (Pax7+/Myf5+) (Kuang et al., 2007). Established experimental approaches to track segregation of old versus nascent DNA involve single or consecutive rounds of halogenated nucleotide analog labels. The thymidine analogue, 5-bromo-2’deoxyuridine (BrdU), can be used to label newly synthesized DNA strands in freshly isolated satellite cells from single fibers. Three days after labeling, single parental cells generated two daughter cells, one BrdU+ and another BrdU-, indicating that template DNA strands can be co-segregated in adult muscle stem cells at a 7% frequency (Shinin et al., 2006). Furthermore, template DNA strands were found to co-segregate with the asymmetric cell fate determinant Numb (Figure 7C). The low frequency observed may be an underestimate owing to the ex vivo culture conditions, but it could be higher if tested in an in vivo tissue context or if investigated to specifically determine DNA inheritance in asymmetrically dividing Pax7+/Myf5- cells. Indeed, later experiments observed an increased frequency (38%) of asymmetric template DNA inheritance in Pax7+/Myf5- cells (Kuang et al., 2007).

During myogenic lineage commitment, satellite cells differentiate and express Desmin, a muscle-specific intermediate filament. In combination with Sca-1 (stem cell antigen-1 protein, a marker for undifferentiated muscle progenitors), cell pairs were examined to determine whether specific templates segregated with specific cell fates. Strikingly, 79% of pairs showed Desmin expression only in the daughter inheriting nascent BrdU+ templates (Conboy et al., 2007). Among pairs whose templates were labeled by BrdU as symmetrically inherited, nearly all were symmetric for Desmin expression. Furthermore, 84% of asymmetric Desmin-positive cells showed asymmetry of Sca-1, demonstrating that older templates co-segregate with the less differentiated cells. An independent study using CO-FISH with single-chromatid resolution demonstrated that asymmetric DNA segregation includes all chromosomes. Based on relative Pax7 levels, a population of high Pax7-expressing satellite cells was characterized to perform template strand co-segregation at a higher frequency (Rocheteau et al., 2012). Together, these experiments provide evidence of template strand co-segregation based on template age, demonstrating that asymmetric co-segregation is associated with cell fate determination. It remains to be elucidated 1) how template strand age is monitored and recognized during cell lineage progression and 2) whether this co-segregation of template DNA is linked to gene regulation or silencing of specific loci in the satellite cells.

Cardiac resident stem cells in neonatal and adult mammalian hearts have been identified by distinct membrane markers and transcription factors, including c-kit and Nkx2.5, respectively (Beltrami et al., 2003). These c-kit-positive endogenous cardiac stem cells (eCSC) are self-renewing, multipotent, and can divide through ACD (Beltrami et al., 2003; Urbanek et al., 2006). Furthermore, these eCSCs have been shown to be necessary and sufficient for myocyte regeneration, leading to anatomical and functional myocardial recovery following myocardial damage (Ellison et al., 2013). The c-kit-positive CSCs were isolated and tested for asymmetric chromatid segregation using the thymidine analogues BrdU and IdU in combination with different pulse-chase time points to detect old versus nascent DNA strands (Kajstura et al., 2012; Sundararaman et al., 2012). From 4% to 7% of c-kit-positive CSCs isolated from myocardial samples displayed asymmetric inheritance of nascent DNA detected during anaphase and telophase in two independent studies (Kajstura et al., 2012; Sundararaman et al., 2012). This range significantly exceeds probability that a random segregation of chromatids would yield an asymmetrical distribution of labeled nucleotides. Therefore, further characterization is necessary to determine whether a subpopulation of c-kit-positive CSCs exists and, similar to muscle satellite cells, exhibits increased ACD and nonrandom chromatid segregation. CO-FISH experiments using chromosome-specific probes could address individual chromosome inheritance upon ACD.

Recent examples have also demonstrated chromatid-biased DNA segregation in colon crypt cells (Falconer et al., 2010). To identify sister chromatids, CO-FISH with unidirectional probes specific for centromere and telomere repeats were used in combination with BrdU to label nascent chromosomes. Mice were injected with BrdU hourly for 12 hours to label actively dividing cells; colon tissue was then fixed, sectioned, and subjected to CO-FISH probes. Sister nuclei showing reciprocal, asymmetric CO-FISH fluorescence were found throughout the colon crypt, indicating that sister chromatids of most chromosomes were segregating nonrandomly. However, the asymmetry was observed for only a subset of the sister chromatids in any cell pair within the colon crypt. This reflects a possibility that a subset of colon cells selectively segregates sister chromatids from most, but not all, chromosomes. Whether specific chromatids are selectively captured within these cells remains to be investigated.

To date, several studies have provided evidence for nonrandom DNA segregation in diverse cell types. It is reasonable to ask if this phenomenon is widespread. An earlier study of chromosome strand segregation based on site-specific recombination markers in mouse embryonic stem cells revealed a nonrandom distribution of chromosome 7 (Armakolas and Klar, 2006). However, two recent studies using CO-FISH indicate that this is not the case and that chromosomes are randomly segregated (Falconer et al., 2012; Sauer et al., 2013). Studies using BrdU to follow the ancestral DNA during the first ACD of the C. elegans embryo also failed to detect asymmetric segregation of DNA (Ito and McGhee, 1987). Furthermore, examples of adult stem cells that do not asymmetrically segregate chromosomes include hair follicle stem cells (Sotiropoulou et al., 2008) and hematopoietic stem cells (Kiel et al., 2007). Together, studies so far indicate that asymmetric segregation of DNA strands occurs in some, but not all, stem cell types.

Many types of adult stem cells undergo ACD to balance self-renewal and differentiation for normal tissue homeostasis. Misregulation of any of the molecular mechanisms that control the asymmetric segregation of cell fate determinants during stem cell divisions may result in hyperproliferation of the stem cell compartment, leading to tumorigenesis, or a loss of the stem cell population, resulting in tissue dystrophy (Knoblich, 2010). Previous studies suggest that tumors contain rare cell populations that have stem cell properties, and when injected into immunocompromised mice, they are able to self-renew and generate heterogeneous tumors (Charafe-Jauffret et al., 2009; Cho and Clarke, 2008; Vermeulen et al., 2008). These studies indicate that a subpopulation of tumor cells can self-renew and repopulate the heterogeneous tumor, suggesting tumor cell repopulation may occur via ACD within subpopulations of tumor cells. Recent studies in both primary lung cancer cells and cells lines indicate a subset of cells that divide asymmetrically, segregating their template DNA strands exclusively to one daughter cell (Pine et al., 2010). Specifically, double-label experiments using IdU and CldU (chlorodeoxyuridine) in combination with real-time imaging in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells demonstrated that old template strand DNA segregated asymmetrically in anaphase and telophase cells. Of the seven NSCLC cell lines examined, asymmetric segregation of template DNA ranging from 0.5% to 6.8% was observed. Furthermore, primary NSCLC tumors displayed an enriched population of cells that asymmetrically segregated template DNA, ranging from 12.5% to 18%, which could reflect an increased concentration of asymmetrically dividing cells within the primary tumor or upon ex vivo expansion. Segregation of the template DNA strands correlated significantly with distinct cell fate markers, including co-segregation with cell fate marker CD113, labeling a tumor subpopulation that could repopulate the entire cell population of lung tumor cells in vitro and in vivo (Bertolini et al., 2009; Eramo et al., 2008). Although these studies have uncovered a significant population of lung cancer primary cells and cell lines able to coordinate asymmetric segregation of template DNA, our understanding of the cell fate choices influenced by this asymmetry is limited and awaits further investigation.

Conclusions

One of the greatest discoveries in the 20th century was the double helix structure and semiconservative duplicating process of DNA, providing an elegant and fundamental principle of life. However, as discussed here and reviewed in (Snedeker et al., 2017), the inherent asymmetry of DNA replication and the increasing knowledge about the polarity in mitosis raise some questions. Further research will explore whether symmetric outcome arises from tightly regulated asymmetric molecular and cellular processes, or whether symmetry is the default pathway and is then broken by asymmetric processes.

In reality, both symmetric and asymmetric outcomes are required to build up a multicellular organism originating from a single cell, a fertilized egg, to produce an individual human being made up of hundreds of cell types. Even though most cells in our bodies carry identical DNA sequences, only a subset of these sequences turn on expression at the proper time, in the right place, and with the precise level during development and homeostasis. It is well recognized that the distinct epigenetic information contained in each cell type defines its unique gene expression program. However, how the epigenetic information contained in the parental cell can be maintained, or changed, in the daughter cells remains largely unknown. This question is extremely difficult to address because the epigenome is composed of numerous components that dynamically change their composition. Nonetheless, this question is central to our understanding of the fundamental principles of biology and our ability to develop new treatments against human diseases including birth defects, neurodegenerative disease, tissue dystrophy, infertility, and cancers. Asymmetric histone inheritance could represent the mechanism that maintains equilibrium between the rigidity of genetic information and the plasticity of epigenetic information. We anticipate that future work will address whether this mechanism is utilized at specific gene loci for differential gene expression upon ACD and whether this mechanism is also applicable to other cell types or in other organisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH F32GM119347–02 (R.J.G), NIH F31 GM122339 (E.W.K.), NIH RO1GM112008, and R21HD084959; the David and Lucile Packard Foundation; Faculty Scholar from Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Simons Foundation and Johns Hopkins University start-up (X.C.).

References

- Alabert C, Barth TK, Reverón-Gómez N, Sidoli S, Schmidt A, Jensen ON, Imhof A and Groth A (2015). Two distinct modes for propagation of histone PTMs across the cell cycle. Genes Dev 29, 585–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alabert C and Groth A (2012). Chromatin replication and epigenome maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13, 153–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allshire RC and Karpen GH (2008). Epigenetic regulation of centromeric chromatin: old dogs, new tricks? Nat Rev Genet 9, 923–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CT and Stearns T (2009). Centriole age underlies asynchronous primary cilium growth in mammalian cells. Curr Biol 19, 1498–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelgren H, Kniola B and Ekwall K (2003). Distinct centromere domain structures with separate functions demonstrated in live fission yeast cells. J Cell Sci 116, 4035–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armakolas A and Klar AJ (2006). Cell type regulates selective segregation of mouse chromosome 7 DNA strands in mitosis. Science 311, 1146–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa H, Hayashi A, Haraguchi T and Hiraoka Y (2005). Dissociation of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex releases centromeres from the spindle-pole body during meiotic prophase in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell 16, 2325–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audergon PN, Catania S, Kagansky A, Tong P, Shukla M, Pidoux AL and Allshire RC (2015). Epigenetics. Restricted epigenetic inheritance of H3K9 methylation. Science 348, 132–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyanathan K, Lechner MS, Bell P, Maul GG, Schultz DC, Yamada Y, Tanaka K, Torigoe K and Rauscher FJ (2003). Regulated recruitment of HP1 to a euchromatic gene induces mitotically heritable, epigenetic gene silencing: a mammalian cell culture model of gene variegation. Genes Dev 17, 1855–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan L and Bambara RA (2013). Okazaki fragment metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambara RA, Murante RS and Henricksen LA (1997). Enzymes and reactions at the eukaryotic DNA replication fork. J Biol Chem 272, 4647–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, Kasahara H, Rota M, Musso E, Urbanek K et al. (2003). Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell 114, 763–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard P, Maure JF, Partridge JF, Genier S, Javerzat JP and Allshire RC (2001). Requirement of heterochromatin for cohesion at centromeres. Science 294, 2539–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini G, Roz L, Perego P, Tortoreto M, Fontanella E, Gatti L, Pratesi G, Fabbri A, Andriani F, Tinelli S et al. (2009). Highly tumorigenic lung cancer CD133+ cells display stem-like features and are spared by cisplatin treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 16281–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BESSMAN MJ, KORNBERG A, LEHMAN IR and SIMMS ES (1956). Enzymic synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta 21, 197–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BESSMAN MJ, LEHMAN IR, SIMMS ES and KORNBERG A (1958). Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid. II. General properties of the reaction. J Biol Chem 233, 171–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi E and Park HO (2012). Cell polarization and cytokinesis in budding yeast. Genetics 191, 347–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobola N, Jansen RP, Shin TH and Nasmyth K (1996). Asymmetric accumulation of Ash1p in postanaphase nuclei depends on a myosin and restricts yeast mating-type switching to mother cells. Cell 84, 699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess RJ and Zhang Z (2013). Histone chaperones in nucleosome assembly and human disease. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20, 14–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns J (1975). Mutation selection and the natural history of cancer. Nature 255, 197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmena A (2008). Signaling networks during development: the case of asymmetric cell division in the Drosophila nervous system. Dev Biol 321, 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayrou C, Coulombe P, Vigneron A, Stanojcic S, Ganier O, Peiffer I, Rivals E, Puy A, Laurent-Chabalier S, Desprat R et al. (2011). Genome-scale analysis of metazoan replication origins reveals their organization in specific but flexible sites defined by conserved features. Genome Res 21, 1438–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerritelli SM and Crouch RJ (2009). Ribonuclease H: the enzymes in eukaryotes. FEBS J 276, 1494–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charafe-Jauffret E, Ginestier C, Iovino F, Wicinski J, Cervera N, Finetti P, Hur MH, Diebel ME, Monville F, Dutcher J et al. (2009). Breast cancer cell lines contain functional cancer stem cells with metastatic capacity and a distinct molecular signature. Cancer Res 69, 1302–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Xiong J, Xu M, Chen S and Zhu B (2011). Symmetrical modification within a nucleosome is not required globally for histone lysine methylation. EMBO Rep 12, 244–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmatal L, Gabriel SI, Mitsainas GP, Martinez-Vargas J, Ventura J, Searle JB, Schultz RM and Lampson MA (2014). Centromere strength provides the cell biological basis for meiotic drive and karyotype evolution in mice. Curr Biol 24, 2295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho RW and Clarke MF (2008). Recent advances in cancer stem cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev 18, 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins CA, Olsen I, Zammit PS, Heslop L, Petrie A, Partridge TA and Morgan JE (2005). Stem cell function, self-renewal, and behavioral heterogeneity of cells from the adult muscle satellite cell niche. Cell 122, 289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy MJ, Karasov AO and Rando TA (2007). High incidence of non-random template strand segregation and asymmetric fate determination in dividing stem cells and their progeny. PLoS Biol 5, e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduit PT and Raff JW (2010). Cnn dynamics drive centrosome size asymmetry to ensure daughter centriole retention in Drosophila neuroblasts. Curr Biol 20, 2187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin E (1905). The organization and cell lineage of the ascidian egg In J. Acad., Nat. Sci. Phila,, (ed., pp. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cosma MP (2004). Daughter-specific repression of Saccharomyces cerevisiae HO: Ash1 is the commander. EMBO Rep 5, 953–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgaard JZ and Klar AJ (1999). Orientation of DNA replication establishes mating-type switching pattern in S. pombe. Nature 400, 181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgaard JZ and Klar AJ (2001). A DNA replication-arrest site RTS1 regulates imprinting by determining the direction of replication at mat1 in S. pombe. Genes Dev 15, 2060–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison GM, Vicinanza C, Smith AJ, Aquila I, Leone A, Waring CD, Henning BJ, Stirparo GG, Papait R, Scarfo M et al. (2013). Adult c-kit(pos) cardiac stem cells are necessary and sufficient for functional cardiac regeneration and repair. Cell 154, 827–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eramo A, Lotti F, Sette G, Pilozzi E, Biffoni M, Di Virgilio A, Conticello C, Ruco L, Peschle C and De Maria R (2008). Identification and expansion of the tumorigenic lung cancer stem cell population. Cell Death Differ 15, 504–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconer E, Chavez EA, Henderson A, Poon SS, McKinney S, Brown L, Huntsman DG and Lansdorp PM (2010). Identification of sister chromatids by DNA template strand sequences. Nature 463, 93–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconer E, Hills M, Naumann U, Poon SS, Chavez EA, Sanders AD, Zhao Y, Hirst M and Lansdorp PM (2012). DNA template strand sequencing of single-cells maps genomic rearrangements at high resolution. Nat Methods 9, 1107–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y and Spector DL (2005). Centromere positioning and dynamics in living Arabidopsis plants. Mol Biol Cell 16, 5710–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennell A, Fernandez-Alvarez A, Tomita K and Cooper JP (2015). Telomeres and centromeres have interchangeable roles in promoting meiotic spindle formation. J Cell Biol 208, 415–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Alvarez A, Bez C, O’Toole ET, Morphew M and Cooper JP (2016). Mitotic Nuclear Envelope Breakdown and Spindle Nucleation Are Controlled by Interphase Contacts between Centromeres and the Nuclear Envelope. Dev Cell 39, 544–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro T, Esposito E, Mancini L, Ng S, Lucas T, Coppey M, Dostatni N, Walczak AM, Levine M and Lagha M (2016). Transcriptional Memory in the Drosophila Embryo. Curr Biol 26, 212–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransz P, De Jong JH, Lysak M, Castiglione MR and Schubert I (2002). Interphase chromosomes in Arabidopsis are organized as well defined chromocenters from which euchromatin loops emanate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 14584–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki H, Hagan I, Uzawa S and Yanagida M (1993). Cell cycle-dependent specific positioning and clustering of centromeres and telomeres in fission yeast. J Cell Biol 121, 961–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furusawa M (2014). The disparity mutagenesis model predicts rescue of living things from catastrophic errors. Front Genet 5, 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenatri M, Bailly D, Maison C and Almouzni G (2004). Mouse centric and pericentric satellite repeats form distinct functional heterochromatin. J Cell Biol 166, 493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber JE (2012). Mating-type genes and MAT switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 191, 33–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond CM, Strømme CB, Huang H, Patel DJ and Groth A (2017). Histone chaperone networks shaping chromatin function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18, 141–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KH, Bracken AP, Pasini D, Dietrich N, Gehani SS, Monrad A, Rappsilber J, Lerdrup M and Helin K (2008). A model for transmission of the H3K27me3 epigenetic mark. Nat Cell Biol 10, 1291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson SJ and Wolfe KH (2017). An Evolutionary Perspective on Yeast Mating-Type Switching. Genetics 206, 9–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S, Ahmad K and Malik HS (2001). The centromere paradox: stable inheritance with rapidly evolving DNA. Science 293, 1098–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S and Malik HS (2002). Centromeres: selfish drivers. Nature 417, 227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz HM, Morgan M, Gao X, Jackson J, Rickels R, Swanson SK, Florens L, Washburn MP, Eissenberg JC and Shilatifard A (2014). Histone H3 lysine-to-methionine mutants as a paradigm to study chromatin signaling. Science 345, 1065–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K and McGhee JD (1987). Parental DNA strands segregate randomly during embryonic development of Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell 49, 329–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson V and Chalkley R (1981). A new method for the isolation of replicative chromatin: selective deposition of histone on both new and old DNA. Cell 23, 121–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson V and Chalkley R (1985). Histone segregation on replicating chromatin. Biochemistry 24, 6930–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JJ and van Lohuizen M (2002). Polycomb repression: from cellular memory to cellular proliferation and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1602, 151–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jambhekar A, McDermott K, Sorber K, Shepard KA, Vale RD, Takizawa PA and DeRisi JL (2005). Unbiased selection of localization elements reveals cis-acting determinants of mRNA bud localization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 18005–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Januschke J, Llamazares S, Reina J and Gonzalez C (2011). Drosophila neuroblasts retain the daughter centrosome. Nat Commun 2, 243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q, Trelles-Sticken E, Scherthan H and Loidl J (1998). Yeast nuclei display prominent centromere clustering that is reduced in nondividing cells and in meiotic prophase. J Cell Biol 141, 21–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajstura J, Bai Y, Cappetta D, Kim J, Arranto C, Sanada F, D’Amario D, Matsuda A, Bardelli S, Ferreira-Martins J et al. (2012). Tracking chromatid segregation to identify human cardiac stem cells that regenerate extensively the infarcted myocardium. Circ Res 111, 894–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Katajisto P, Dohla J, Chaffer CL, Pentinmikko N, Marjanovic N, Iqbal S, Zoncu R, Chen W, Weinberg RA and Sabatini DM (2015). Stem cells. Asymmetric apportioning of aged mitochondria between daughter cells is required for stemness. Science 348, 340–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima SA, Tsukahara T, Langegger M, Hauf S, Kitajima TS and Watanabe Y (2007). Shugoshin enables tension-generating attachment of kinetochores by loading Aurora to centromeres. Genes Dev 21, 420–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel MJ, He S, Ashkenazi R, Gentry SN, Teta M, Kushner JA, Jackson TL and Morrison SJ (2007). Haematopoietic stem cells do not asymmetrically segregate chromosomes or retain BrdU. Nature 449, 238–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klar AJ (1994). A model for specification of the left-right axis in vertebrates. Trends Genet 10, 392–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klar AJ (2007). Lessons learned from studies of fission yeast mating-type switching and silencing. Annu Rev Genet 41, 213–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblich JA (2008). Mechanisms of asymmetric stem cell division. Cell 132, 583–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblich JA (2010). Asymmetric cell division: recent developments and their implications for tumour biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11, 849–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg A, Lehman IR, Bessman MJ and Simms ES (1989). Enzymic synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid. 1956. Biochim Biophys Acta 1000, 57–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S, Kuroda K, Le Grand F and Rudnicki MA (2007). Asymmetric self-renewal and commitment of satellite stem cells in muscle. Cell 129, 999–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston LD, Zhang D, Yurieva O, Georgescu RE, Finkelstein J, Yao NY, Indiani C and O’Donnell ME (2014). CMG helicase and DNA polymerase epsilon form a functional 15-subunit holoenzyme for eukaryotic leading-strand DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 15390–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdorp PM (2007). Immortal strands? Give me a break. Cell 129, 1244–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffak IM, Grainger R and Weintraub H (1977). Conservative assembly and segregation of nucleosomal histones. Cell 12, 837–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEHMAN IR, BESSMAN MJ, SIMMS ES and KORNBERG A (1958). Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid. I. Preparation of substrates and partial purification of an enzyme from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 233, 163–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Yuan ZF, Han Y, Marchione DM and Garcia BA (2016). Preferential Phosphorylation on Old Histones during Early Mitosis in Human Cells. J Biol Chem 291, 15342–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long RM, Singer RH, Meng X, Gonzalez I, Nasmyth K and Jansen RP (1997). Mating type switching in yeast controlled by asymmetric localization of ASH1 mRNA. Science 277, 383–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik HS (2009). The centromere-drive hypothesis: a simple basis for centromere complexity. Prog Mol Subcell Biol 48, 33–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margueron R, Justin N, Ohno K, Sharpe ML, Son J, Drury WJ, Voigt P, Martin SR, Taylor WR, De Marco V et al. (2009). Role of the polycomb protein EED in the propagation of repressive histone marks. Nature 461, 762–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight SL and Miller OL (1977). Electron microscopic analysis of chromatin replication in the cellular blastoderm Drosophila melanogaster embryo. Cell 12, 795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekhail K and Moazed D (2010). The nuclear envelope in genome organization, expression and stability. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11, 317–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meselson M and Stahl FW (1958). THE REPLICATION OF DNA IN ESCHERICHIA COLI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 44, 671–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misteli T (2007). Beyond the sequence: cellular organization of genome function. Cell 128, 787–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki R, Okazaki T, Sakabe K, Sugimoto K and Sugino A (1968). Mechanism of DNA chain growth. I. Possible discontinuity and unusual secondary structure of newly synthesized chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 59, 598–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer DK, O’Day K, Wener MH, Andrews BS and Margolis RL (1987). A 17-kD centromere protein (CENP-A) copurifies with nucleosome core particles and with histones. J Cell Biol 104, 805–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier L and Yamashita YM (2012). Centrosome asymmetry and inheritance during animal development. Curr Opin Cell Biol 24, 541–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira G and Yamashita YM (2011). Fly meets yeast: checking the correct orientation of cell division. Trends Cell Biol 21, 526–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CL and Laniel MA (2004). Histones and histone modifications. Curr Biol 14, R546–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine SR, Ryan BM, Varticovski L, Robles AI and Harris CC (2010). Microenvironmental modulation of asymmetric cell division in human lung cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 2195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst AV, Dunleavy E and Almouzni G (2009). Epigenetic inheritance during the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10, 192–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragunathan K, Jih G and Moazed D (2015). Epigenetics. Epigenetic inheritance uncoupled from sequence-specific recruitment. Science 348, 1258699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajapakse I and Groudine M (2011). On emerging nuclear order. J Cell Biol 192, 711–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo E, Sampaio P, Januschke J, Llamazares S, Varmark H and Gonzalez C (2007). Functionally unequal centrosomes drive spindle orientation in asymmetrically dividing Drosophila neural stem cells. Dev Cell 12, 467–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhyu MS, Jan LY and Jan YN (1994). Asymmetric distribution of numb protein during division of the sensory organ precursor cell confers distinct fates to daughter cells. Cell 76, 477–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley D and Weintraub H (1979). Conservative segregation of parental histones during replication in the presence of cycloheximide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76, 328–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringrose L and Paro R (2004). Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins. Annu Rev Genet 38, 413–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocheteau P, Gayraud-Morel B, Siegl-Cachedenier I, Blasco MA and Tajbakhsh S (2012). A subpopulation of adult skeletal muscle stem cells retains all template DNA strands after cell division. Cell 148, 112–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi ML, Pike JE, Wang W, Burgers PM, Campbell JL and Bambara RA (2008). Pif1 helicase directs eukaryotic Okazaki fragments toward the two-nuclease cleavage pathway for primer removal. J Biol Chem 283, 27483–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roufa DJ and Marchionni MA (1982). Nucleosome segregation at a defined mammalian chromosomal site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 79, 1810–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusan NM and Peifer M (2007). A role for a novel centrosome cycle in asymmetric cell division. J Cell Biol 177, 13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakabe K and Okazaki R (1966). A unique property of the replicating region of chromosomal DNA. Biochim Biophys Acta 129, 651–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer S, Burkett SS, Lewandoski M and Klar AJ (2013). A CO-FISH assay to assess sister chromatid segregation patterns in mitosis of mouse embryonic stem cells. Chromosome Res 21, 311–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherthan H and Schonborn I (2001). Asynchronous chromosome pairing in male meiosis of the rat (Rattus norvegicus). Chromosome Res 9, 273–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale RL (1976). Studies on the mode of segregation of histone nu bodies during replication in HeLa cells. Cell 9, 423–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman MM, Levine AJ and Weintraub H (1979). The asymmetric segregation of parental nucleosomes during chrosome replication. Cell 18, 439–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard KA, Gerber AP, Jambhekar A, Takizawa PA, Brown PO, Herschlag D, DeRisi JL and Vale RD (2003). Widespread cytoplasmic mRNA transport in yeast: identification of 22 bud-localized transcripts using DNA microarray analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 11429–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinin V, Gayraud-Morel B, Gomes D and Tajbakhsh S (2006). Asymmetric division and cosegregation of template DNA strands in adult muscle satellite cells. Nat Cell Biol 8, 677–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sil A and Herskowitz I (1996). Identification of asymmetrically localized determinant, Ash1p, required for lineage-specific transcription of the yeast HO gene. Cell 84, 711–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedeker J, Wooten M and Chen X (2017). The Inherent Asymmetry of DNA Replication. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogo JM, Stahl H, Koller T and Knippers R (1986). Structure of replicating simian virus 40 minichromosomes. The replication fork, core histone segregation and terminal structures. J Mol Biol 189, 189–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiropoulou PA, Candi A and Blanpain C (2008). The majority of multipotent epidermal stem cells do not protect their genome by asymmetrical chromosome segregation. Stem Cells 26, 2964–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stancheva I, Koller T and Sogo JM (1999). Asymmetry of Dam remethylation on the leading and lagging arms of plasmid replicative intermediates. EMBO J 18, 6542–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundararaman B, Avitabile D, Konstandin MH, Cottage CT, Gude N and Sussman MA (2012). Asymmetric chromatid segregation in cardiac progenitor cells is enhanced by Pim-1 kinase. Circ Res 110, 1169–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh S and Gonzalez C (2009). Biased segregation of DNA and centrosomes: moving together or drifting apart? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10, 804–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe PH, Bruno J and Rothstein R (2009). Kinetochore asymmetry defines a single yeast lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 6673–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita K, Bez C, Fennell A and Cooper JP (2013). A single internal telomere tract ensures meiotic spindle formation. EMBO Rep 14, 252–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita K and Cooper JP (2007). The telomere bouquet controls the meiotic spindle. Cell 130, 113–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran V, Feng L and Chen X (2013). Asymmetric distribution of histones during Drosophila male germline stem cell asymmetric divisions. Chromosome Res 21, 255–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran V, Lim C, Xie J and Chen X (2012). Asymmetric division of Drosophila male germline stem cell shows asymmetric histone distribution. Science 338, 679–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BM (2002). Cellular memory and the histone code. Cell 111, 285–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek K, Cesselli D, Rota M, Nascimbene A, De Angelis A, Hosoda T, Bearzi C, Boni A, Bolli R, Kajstura J et al. (2006). Stem cell niches in the adult mouse heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 9226–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rossum B, Fischle W and Selenko P (2012). Asymmetrically modified nucleosomes expand the histone code. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19, 1064–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashee S, Cvetic C, Lu W, Simancek P, Kelly TJ and Walter JC (2003). Sequence-independent DNA binding and replication initiation by the human origin recognition complex. Genes Dev 17, 1894–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasseur P, Tonazzini S, Ziane R, Camasses A, Rando OJ and Radman-Livaja M (2016). Dynamics of Nucleosome Positioning Maturation following Genomic Replication. Cell Rep 16, 2651–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengrova S and Dalgaard JZ (2004). RNase-sensitive DNA modification(s) initiates S. pombe mating-type switching. Genes Dev 18, 794–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengrova S and Dalgaard JZ (2006). The wild-type Schizosaccharomyces pombe mat1 imprint consists of two ribonucleotides. EMBO Rep 7, 59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen L, Sprick MR, Kemper K, Stassi G and Medema JP (2008). Cancer stem cells--old concepts, new insights. Cell Death Differ 15, 947–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt P, LeRoy G, Drury WJ, Zee BM, Son J, Beck DB, Young NL, Garcia BA and Reinberg D (2012). Asymmetrically modified nucleosomes. Cell 151, 181–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Tsai JW, Imai JH, Lian WN, Vallee RB and Shi SH (2009). Asymmetric centrosome inheritance maintains neural progenitors in the neocortex. Nature 461, 947–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub H (1976). Cooperative alignment of nu bodies during chromosome replication in the presence of cycloheximide. Cell 9, 419–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TA, Bordewich M and Searle JB (2010). A network approach to study karyotypic evolution: the chromosomal races of the common shrew (Sorex araneus) and house mouse (Mus musculus) as model systems. Syst Biol 59, 262–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Wooten M, Tran V, Chen BC, Pozmanter C, Simbolon C, Betzig E and Chen X (2015). Histone H3 Threonine Phosphorylation Regulates Asymmetric Histone Inheritance in the Drosophila Male Germline. Cell 163, 920–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Wooten M, Tran V and Chen X (2017). Breaking Symmetry - Asymmetric Histone Inheritance in Stem Cells. Trends Cell Biol 27, 527–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Long C, Chen X, Huang C, Chen S and Zhu B (2010). Partitioning of histone H3-H4 tetramers during DNA replication-dependent chromatin assembly. Science 328, 94–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]