Abstract

Importance

Conjunctival melanoma has the potential for regional lymphatic and distant metastasis. There is an urgent need for effective treatment for patients with metastatic or locally advanced conjunctival melanoma.

Objective

To describe the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of conjunctival melanoma in 5 adult patients.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective review was conducted of the medical records of 5 patients with conjunctival melanoma who were treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors from March 6, 2013, to July 7, 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Response to treatment and disease-free survival.

Results

Of the 5 patients (4 women and 1 man) with metastatic conjunctival melanoma, 4 were treated with a programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) inhibitor, nivolumab, and had a complete response to treatment with no evidence of disease at 1, 7, 9, and 36 months after completing treatment. One patient with metastatic conjunctival melanoma was treated with another PD-1 inhibitor, pembrolizumab, and had stable metastases during the first 6 months of treatment. Later disease progression resulted in treatment cessation after 11 months and switching to another therapy. Two patients treated with nivolumab developed autoimmune colitis that necessitated stopping the immunotherapy; these patients subsequently were managed with systemic corticosteroids or infliximab.

Conclusions and Relevance

This case series report suggests that anti–PD-1 therapy can be used to treat metastatic conjunctival melanoma. Longer follow-up is needed to determine the long-term disease-free survival. Future studies might assess the potential for immune checkpoint inhibitors to obviate the need for orbital exenteration in selected patients with locally advanced disease.

This cohort study describes the use of programmed cell death 1 inhibitors for the treatment of metastatic conjunctival melanoma in 5 adult patients.

Key Points

Question

Can programmed cell death 1 inhibitors be used to treat conjunctival melanoma with metastases?

Findings

In this case series study, 4 patients with metastatic conjunctival melanoma treated with nivolumab had a complete response to treatment with no evidence of disease at 1, 7, 9, and 36 months after completing treatment. One patient treated with pembrolizumab had initial stable disease but progressed after 11 months of therapy.

Meaning

These results suggest that programmed cell death 1 inhibitors can be used to treat metastatic conjunctival melanoma.

Introduction

Conjunctival melanoma is a rare tumor with the potential to invade the eye, eyelid, and orbit and spread to regional lymphatics and distant sites, including the lungs, skin, liver, and brain. It was previously reported to have local recurrence rates of 36% to 45% at 5 years and 31% to 59% at 10 years.1 Lymph node involvement was found in 19% of patients with conjunctival melanoma and systemic metastases were found in 19% of patients within 10 years after initial diagnosis.1,2 Melanoma-related death was reported in 9% to 18% of patients at 5 years.1,2,3 The mainstay of treatment for local control is surgical excision with margins clear of tumor; locally advanced disease may necessitate an orbital exenteration. Adjuvant treatments include topical chemotherapy and radiotherapy and are aimed at improving local control. Historically, treatment options for metastatic conjunctival melanoma have been limited.

In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors, a new class of drugs, have been successfully used to treat metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Immune checkpoint inhibitors prevent cancer cells from activating mechanisms that enable the cells to evade the host’s immune system. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, by blocking receptors on the surface of activated T lymphocytes, such as programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), facilitate the recognition of cancer cells by lymphocytes and a consequent effective immune response. Ipilimumab (a CTLA-4 inhibitor), pembrolizumab (a PD-1 inhibitor), and nivolumab (a PD-1 inhibitor) are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of metastatic cutaneous melanoma; nivolumab and ipilimumab are also approved for the treatment of unresectable cutaneous melanoma.4,5,6 Large-scale studies have reported improved survival of patients with metastatic or unresectable cutaneous melanoma treated with these drugs.7,8,9

Since 2013, we have used PD-1 inhibitors for our patients with metastatic conjunctival melanoma given that no drugs are approved for this rare form of melanoma. We present our experience treating 5 patients with metastatic conjunctival melanoma with PD-1 inhibitors.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of the medical records of all 5 patients with conjunctival melanoma who were treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors under the care of one of us (B.E.) from March 6, 2013, to July 7, 2017. The medical records were reviewed for clinical and pathologic findings, treatments, and outcomes. This study was deemed exempt by the institutional review board of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center because this report was a collection of 5 individual cases; the institutional review board of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center exempts such reports from full review and continuing reviews, as no generalizable information is given. Information was obtained and reported in a manner that was compliant with the standards set forth by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the Declaration of Helsinki.10

In January 2018, PubMed was searched to identify publications with the key term conjunctival melanoma in combination with 1 or more of the following key terms: immune checkpoint inhibitors, ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, and nivolumab.

Results

The clinical features, treatments, and outcome of all patients are summarized in the Table.

Table. Clinical Data for 5 Patients With Metastatic Conjunctival Melanoma Treated With PD-1 Inhibitors.

| Patient No./Sex/Age, y | Ocular Status | Locations of Metastases | Treatment | Duration of Treatment, mo | Ocular Response | Systemic Response | Follow-up After Treatment, mo | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/F/58 | After orbital exenteration, recurrence at ipsilateral orbital rim | Lungs, liver | Nivolumab | 3 | Complete response | Complete response | 9 | Alive without disease |

| 2/F/28 | No evidence of disease | Breast, lungs, clavicle, thigh | Nivolumab | 3.5 | Unchanged | Complete response | 36 | Alive without disease |

| 3/F/47 | No evidence of disease | Lungs | Nivolumab | 5 | Unchanged | Complete response | 7 | Alive without disease |

| 4/F/68 | After orbital exenteration, no evidence of disease | Lungs | Pembrolizumab | 11 | Unchanged | Stable disease at 6 mo, then progression | 2a | Alive with disease |

| 5/M/74 | Recurrent microscopic disease present | Lungs | Nivolumab | 11 | Complete response | Complete response | 1 | Alive without disease |

Abbreviation: PD-1, programmed cell death 1.

This patient’s therapy was switched to an alternative treatment owing to progression.

Patient 1

A white woman in her 50s with a history of recurrent conjunctival melanoma of the right eye was referred to our center. She had undergone multiple surgical resections, a right parotidectomy, and eventually an orbital exenteration. Pathologic evaluation of the exenteration specimen revealed a conjunctival melanoma with a thickness of 5.5 mm and 11 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields (hpf). One year after exenteration, the patient developed a new local recurrence in the right orbital socket, which was biopsied and confirmed to be invasive melanoma with a thickness of 1.9 mm and 18 mitotic figures per 10 hpf. At this point, she was referred to our center.

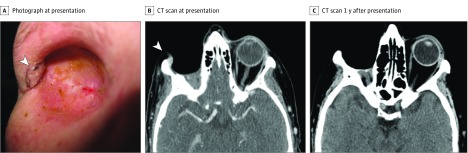

On clinical examination, a 12 × 15-mm nodular mass was detected along the lateral wall of the orbital socket (Figure 1A and B). A positron emission tomography and computed tomography scan demonstrated metastatic lesions in the lungs and liver. The patient was subsequently treated with intravenous nivolumab, 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks. After 3 months of therapy, treatment was discontinued because the patient had elevated liver enzyme levels. Computed tomography showed a response to treatment in lesions in the orbit, lung, and liver (Figure 1C). At follow-up 9 months after discontinuation of nivolumab, the patient had complete resolution of the orbital and metastatic lesions, and no evidence of disease was detected after clinical examination or on imaging scans.

Figure 1. Local Recurrence of Conjunctival Melanoma in the Right Orbital Socket 1 Year After Orbital Exenteration in Patient 1.

A, Clinical photograph at presentation to our center. The patient had a 12 × 15-mm nodular mass along the lateral wall of the orbital socket (arrowhead) with adjacent areas of macroscopic ulceration (posterior to the nodule, which is not shown). B, Computed tomography (CT) scan at presentation demonstrating a contrast-enhancing nodule at the anterior lateral orbital wall (arrowhead). C, CT scan 1 year after presentation, after 3 months of treatment with nivolumab and 9 months of additional follow-up without treatment. There is no evidence of local recurrence.

Patient 2

A white woman in her 20s with recurrent conjunctival melanoma of the left eye was referred to our center for treatment of a new recurrence. Pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen prior to referral to our center demonstrated a tumor thickness of 1.95 mm, 5 mitotic figures per 10 hpf, and positive margins.

The patient underwent a wide local excision, cryotherapy to the surgical margins, and 2 cycles of adjuvant topical mitomycin C, 0.02% (drops), each cycle consisting of 1 drop 4 times a day for 7 days followed by 7 days with no treatment. She had no evidence of disease during 19 months of follow-up, after which she was lost to follow-up because of insurance issues.

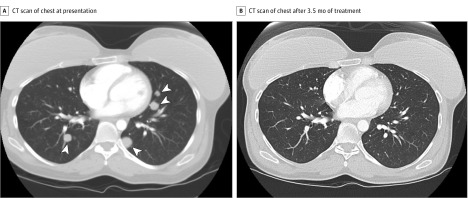

The patient presented to our center again 5 years after her initial presentation with a palpable mass in the right breast, which was biopsied and confirmed to be metastatic melanoma. A workup for systemic disease revealed additional metastases in the lungs, left clavicle, and right thigh, but no recurrence in the periocular area (Figure 2A). The patient was treated with intravenous nivolumab, 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks, for 7 cycles. After completion of the first cycle, computed tomography demonstrated a partial response of the metastases. After 3.5 months of treatment, the patient achieved a complete response (Figure 2B). She remained disease free 3 years after completion of nivolumab treatment. This patient was included in a previous report with shorter follow-up.11

Figure 2. Patient 2 With a History of Recurrent Conjunctival Melanoma Treated With a Wide Local Excision, Cryotherapy, and 2 Cycles of Adjuvant Mitomycin C Drops.

The patient presented 6 years later with multiple metastases to the lungs, breast, left clavicle, and right thigh. A, Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, with contrast showing innumerable small nodules in both lungs, with the largest one in the left lung base measuring 1.7 × 1.6 cm (arrowheads). B, CT scan of the chest after 3.5 months of treatment with the programmed cell death 1 inhibitor nivolumab, with contrast showing complete response to treatment with resolution of all metastatic lesions.

Patient 3

A white woman in her 40s with a history of recurrent conjunctival melanoma of the right eye was referred to our center. The patient had initially been diagnosed with a conjunctival melanoma with a thickness of 0.08 mm without histologic ulceration. She had undergone multiple treatments, including a wide local excision and cryotherapy; 3 plaque radiotherapy treatments; a parotidectomy, which revealed lymph node metastases; and a subsequent modified neck lymphadenectomy, the specimen from which was negative for tumor. She was then treated with adjuvant topical interferon. After 1 year of interferon therapy, she developed a local recurrence, which was treated with surgical resection and cryotherapy. The patient was then referred to our center for further evaluation, 7 years after the initial diagnosis of conjunctival melanoma.

At presentation to our center, the patient had no clinical or radiologic evidence of local or distant gross disease. She was therefore treated with 2 cycles of adjuvant topical mitomycin C, 0.02% (drops), according to the regimen described for patient 2. Subsequently, the patient had regular follow-up examinations at our center. She was free from signs of disease until 6.5 years after completion of mitomycin C therapy, when imaging revealed a new opacity of the lower lobe of the right lung, which was biopsied and diagnosed as metastatic melanoma.

The patient was treated with intravenous nivolumab, 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks, and experienced resolution of the lung metastasis after 4 cycles of treatment. After 10 cycles (5 months) of treatment, the patient developed persistent diarrhea, and imaging demonstrated mucosal thickening affecting the colon, consistent with drug-induced autoimmune colitis. Anti–PD-1 therapy was discontinued, and the colitis was treated and controlled with prednisone and infliximab. At last follow-up, 7 months after discontinuation of nivolumab, the patient remained clinically free of disease.

Patient 4

A white woman in her 60s with a history of recurrent conjunctival melanoma involving the right bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva, who was previously treated with repeated surgical resections and adjuvant topical mitomycin C, presented to our center 5 years after initial diagnosis for further evaluation and treatment. She was found to have a severely scarred cornea and eyelids, a locally recurrent invasive melanoma with a thickness of at least 2 mm, 1 mitotic figure per 10 hpf, perineural invasion, and no evidence of regional or distant metastases. She was treated with an orbital exenteration, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and parotidectomy; the surgical specimens were negative for tumor. After surgery, she was treated with 30 Gy of radiotherapy to the right orbit, given the high-risk features of her disease.

Two years after the completion of radiotherapy, on a routine surveillance visit, chest radiography revealed pulmonary nodules. These were biopsied and diagnosed as metastatic melanoma negative for the BRAF (OMIM 164757) V600E mutation. The patient started treatment with intravenous pembrolizumab, 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks. During the first 6 months of treatment, the metastases were stable, but at the 11-month follow-up visit (after 13 treatment cycles), therapy was discontinued because of minor progression of the metastases and development of minor tracheoesophageal and periesophageal lymphadenopathy. Therapy was then switched to intravenous ipilimumab, 3 mg/kg, combined with intravenous dacarbazine, 800 mg/m2 to 1000 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. At the time of writing, the patient had received 2 cycles of treatment, which was stopped owing to grade 4 hepatotoxic effects, with partial response improvement of her metastases.

Patient 5

A white man in his 70s with a history of melanoma of the left conjunctiva and upper and lower eyelids was referred to our center. The patient had experienced multiple recurrences and undergone multiple surgical excisions during the 16 years after initial diagnosis and had recently developed another local recurrence involving the left lower eyelid. This was resected elsewhere, and evaluation of the resection specimen revealed melanoma with a thickness of 2.9 mm, 8 mitotic figures per 10 hpf, histologic ulceration, and no perineural invasion present at tissue edges. At presentation to our center, the patient had no clinical or radiologic evidence of gross residual local disease. Orbital exenteration was recommended given the extent of the recurrent disease and the lack of sufficient healthy tissue for reconstruction of the ocular surface and eyelids, but the patient declined.

Two months later, restaging scans revealed an enlarging pulmonary mass in the upper lobe of the right lung, suspected to be metastatic melanoma. The patient started receiving intravenous nivolumab, 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks. After 3 months (6 cycles) of treatment, imaging revealed an interval decrease in tumor size. After 11 months, treatment was discontinued because of immune-related colitis, which was treated with systemic prednisone. At the most recent follow-up, 1 month after discontinuation of nivolumab, restaging scans demonstrated no evidence of gross local or distant disease, and the patient reported improvement of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Discussion

In this series of 5 patients with metastatic conjunctival melanoma treated with anti–PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors, 4 patients had a complete response to treatment, with no evidence of disease at 1, 7, 9, and 36 months after completion of therapy. A fifth patient had stable metastatic disease for 6 months while undergoing treatment.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have shown substantial clinical benefit in patients with metastatic cutaneous melanoma, as reported in multiple large studies.7,8,9 A 2013 study screened 78 conjunctival melanomas for a panel of oncogene “hotspot mutations” and analyzed genome-wide DNA copy number alterations.12 The authors concluded that the mutation profile of conjunctival melanoma is similar to that of cutaneous or mucosal melanomas but distinct from uveal melanoma. This similarity suggests that established treatments for cutaneous melanoma should be investigated for conjunctival melanoma. Cao et al13 analyzed the expression of PD-1 and PD-ligand-1 (PD-L1) and the density of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in 27 specimens of primary conjunctival melanomas. They found PD-L1 expression on tumor cells in 19% of cases, and that this expression was associated with distant metastases and poorer melanoma-related survival. In vivo results also showed that PD-L1 expression on tumor cells could be up-regulated with stimulation by interferon γ. Taken together, and given the proven efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors for cutaneous melanoma, these findings give a reasonable theoretical basis for a trial of treatment of patients with metastatic conjunctival melanoma with PD-1 inhibitors. For this reason, since 2013, we have used anti–PD-1 therapy, which is approved for cutaneous melanoma, to treat our patients with metastatic conjunctival melanoma.

In a literature search performed at the time of writing of this report, we did not find any reports on the use of nivolumab for the treatment of primary conjunctival melanoma, and only 1 case report describing a single patient11 (patient 2 in the present study). We found 2 case reports suggesting the use of pembrolizumab for treatment of conjunctival melanoma, both published in 2017.14,15 In a letter to the editor, Kini et al14 reported on the use of pembrolizumab to avoid exenteration in a patient with a recurrent conjunctival melanoma in his only eye with useful vision who developed locally advanced disease with orbital involvement. The patient was treated with pembrolizumab for 6 months before undergoing an eye-sparing surgical excision of the pigmented lesions, with no residual tumor seen on results of pathologic analysis. The authors reported that this patient continued pembrolizumab treatment for an additional year, with no evidence of recurrence. Pinto Torres et al15 reported on a patient with recurrent conjunctival melanoma who, despite good local control, developed metastases to the lymph nodes and skin and was treated with pembrolizumab, with complete remission at 10 months of follow-up. In addition, a previous report described one of the patients in the present report (patient 2) as part of a small series of patients with periocular (eyelid and orbital) melanomas treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors.11 The current series adds to the literature 4 more patients with conjunctival melanoma successfully treated with anti–PD-1 therapy plus additional follow-up information about the 1 previously reported patient. Our current report is also the only report, to our knowledge, of the use of nivolumab as an effective treatment for patients with metastatic conjunctival melanoma.

The adverse effect profile of immune checkpoint inhibitors differs from that of traditional chemotherapy, as it is the result of immune system activation after the release of the PD-1 or CTLA-4 inhibition. Common adverse effects include cutaneous rash, pruritus, colitis, autoimmune hepatitis, pneumonitis, and endocrinopathies such as hypophysitis or thyroid dysfunction. Neuropathy, myositis, and arthritis are less common.16 Ocular adverse effects include dry eyes, episcleritis, uveitis, and orbital inflmmation.17 Two patients in our series developed autoimmune colitis as an adverse reaction to nivolumab. In both cases, nivolumab was stopped, and the colitis was managed successfully with systemic corticosteroids or infliximab. In larger studies of immune checkpoint inhibitors for cutaneous melanoma, serious adverse effects were more common with ipilimumab, 15%, than with nivolumab or pembrolizumab, 5%.16

Limitations

This small retrospective case series has the limitations inherent to observations made in a few patients. Nevertheless, this is the largest series to date of patients with metastatic conjunctival melanoma treated with PD-1 inhibitors, demonstrating their efficacy for this indication.

Conclusions

Longer follow-up is needed to determine long-term disease-free survival. Most of our patients who developed metastatic disease did so despite no evidence of local recurrence. Future studies can carefully assess the potential for PD-1 inhibitors to obviate the need for orbital exenteration in selected patients with locally advanced disease.

References

- 1.Wong JR, Nanji AA, Galor A, Karp CL. Management of conjunctival malignant melanoma: a review and update. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2014;9(3):185-204. doi: 10.1586/17469899.2014.921119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esmaeli B, Roberts D, Ross M, et al. . Histologic features of conjunctival melanoma predictive of metastasis and death (an American Ophthalmological thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2012;110:64-73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shields CL. Conjunctival melanoma: risk factors for recurrence, exenteration, metastasis, and death in 150 consecutive patients. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2000;98:471-492. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Food and Drud Administration YERVOY [package insert]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/125377s074lbl.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2018.

- 5.US Food and Drug Administration KEYTRUDA [package insert]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/125514s015lbl.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2018.

- 6.US Food and Drug Administration OPDIVO [package insert]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/125554s024lbl.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2018.

- 7.Schadendorf D, Hodi FS, Robert C, et al. . Pooled analysis of long-term survival data from phase II and phase III trials of ipilimumab in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1889-1894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaver JA, Theoret MR, Mushti S, et al. . FDA approval of nivolumab for the first-line treatment of patients with BRAFV600 wild-type unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(14):3479-3483. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hazarika M, Chuk MK, Theoret MR, et al. . US FDA approval summary: nivolumab for treatment of unresectable or metastatic melanoma following progression on ipilimumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(14):3484-3488. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford J, Thuro BA, Thakar S, Hwu WJ, Richani K, Esmaeli B. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for treatment of metastatic melanoma of the orbit and ocular adnexa. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(4):e82-e85. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griewank KG, Westekemper H, Murali R, et al. . Conjunctival melanomas harbor BRAF and NRAS mutations and copy number changes similar to cutaneous and mucosal melanomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(12):3143-3152. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao J, Brouwer NJ, Richards KE, et al. . PD-L1/PD-1 expression and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in conjunctival melanoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(33):54722-54734. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kini A, Fu R, Compton C, Miller DM, Ramasubramanian A. Pembrolizumab for recurrent conjunctival melanoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(8):891-892. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.2279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinto Torres S, André T, Gouveia E, Costa L, Passos MJ. Systemic treatment of metastatic conjunctival melanoma. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2017;2017:4623964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emens LA, Ascierto PA, Darcy PK, et al. . Cancer immunotherapy: opportunities and challenges in the rapidly evolving clinical landscape. Eur J Cancer. 2017;81:116-129. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalvin LA, Shields CL, Orloff M, Sato T, Shields JA. Checkpoint inhibitor immune therapy: systemic indications and ophthalmic side effects. Retina. 2018;38(6):1063-1078. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]