Abstract

This survey study investigates education and reporting of diagnostic errors among resident and attending physicians in internal medicine training programs in Connecticut.

In September 2015, the National Academy of Medicine released the landmark report “Improving Diagnosis in Health Care,” which defined diagnostic error as “the failure to (a) establish an accurate and timely explanation of the patient’s health problem(s) or (b) communicate that explanation to the patient.”1 Earlier educational programs that addressed diagnostic error focused on providers' medical knowledge, clinical reasoning, and systems awareness.1,2,3,4 We evaluated physicians’ training for and comfort with communicating diagnostic errors to patients and reporting them to other health care providers.

Methods

From June 2, 2016, through March 29, 2017, we surveyed internal medicine resident and attending physicians from 9 residency programs across 2 university-affiliated and 4 community-affiliated hospitals in Connecticut. Participants received electronic surveys via email or paper-based surveys. After providing participants with the National Academy of Medicine definition of diagnostic error, we asked questions about physicians’ education and reporting of diagnostic errors, including where the physician was taught to discuss diagnostic errors, whether training programs teach residents how to communicate about diagnostic errors, how institutions typically address diagnostic errors, how trainees are encouraged to report diagnostic errors, how comfortable physicians feel reporting diagnostic errors, and whether the participant agreed with the statement “My current reporting system is helpful in reducing diagnostic errors.” We used summary statistics for aggregate responses and Pearson χ2 test for subgroup analyses. The Figure and the Table give data on responses. The Yale-New Haven Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained, and data were deidentified.

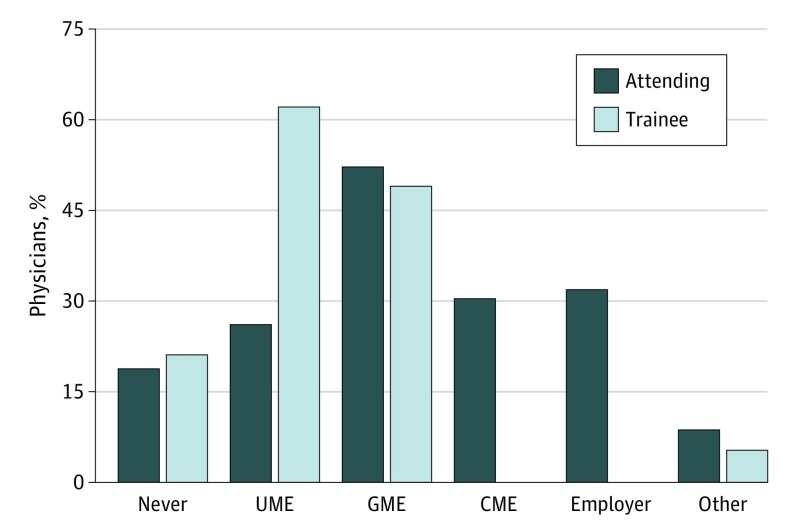

Figure. Education Regarding Discussion of Diagnostic Errors With Patients.

Cumulative responses of attending and trainee physicians to the question of where they were taught to discuss diagnostic errors with patients. Physicians were asked to select all that applied. CME indicates continuing medical education; GME, graduate medical education; and UME, undergraduate medical education.

Table. Comparison of Responses on Education and Reporting of Diagnostic Errors by Resident and Attending Physicians.

| Question | No. (%) of Physicians | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resident (n = 196) | Attending (n = 70) | ||

| Where have you been taught how to discuss diagnostic errors with patients? (Select all that apply) | |||

| Never been formally taught | 40 (21.1) | 13 (18.8) | .70 |

| Medical school | 118 (62.1) | 18 (26.1) | <.001 |

| Residency | 93 (48.9) | 36 (52.2) | .65 |

| Other | 10 (5.3) | 6 (8.7) | .31 |

| Does your training program teach residents how to communicate about diagnostic errors to patients? (Select 1 answer: yes, no, unsure) | |||

| Yes | 83 (43.5) | 44 (64.7) | .001 |

| No or unsure | 108 (56.5) | 24 (35.3) | |

| When a diagnostic error occurs, how does your institution most often address it? (Select 1 answer) | |||

| Not addressed | 15 (8.1) | 7 (10.3) | .67 |

| Informal one-on-one discussion with team member | 80 (43.2) | 24 (35.3) | .21 |

| Formal one-on-one discussion with team member | 23 (12.4) | 12 (17.7) | .17 |

| Formal group discussion with team members (eg, root cause analysis, morbidity and mortality conference) | 67 (36.2) | 25 (36.8) | .46 |

| How are trainees encouraged to report diagnostic errors? (Select all that apply) | |||

| Not encouraged | 21 (11.2) | 5 (7.5) | .38 |

| Senior resident | 111 (59.4) | 30 (44.6) | .04 |

| Chief resident | 39 (20.9) | 22 (32.8) | .05 |

| Attending | 105 (56.2) | 53 (79.1) | .001 |

| Program director | 18 (9.6) | 13 (19.4) | .04 |

| Anonymous reporting system | 95 (50.8) | 42 (62.7) | .09 |

| How comfortable do you feel reporting diagnostic errors when they occur to patients under your care? (Select 1 answer) | |||

| Uncomfortable or very uncomfortable | 83 (44.6) | 21 (30.9) | .05 |

| Comfortable or very comfortable | 103 (55.4) | 47 (69.1) | |

| “My current reporting system is helpful in reducing diagnostic errors.” (Select 1 answer) | |||

| Agree or strongly agree | 106 (57.6) | 37 (56.1) | .83 |

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 78 (42.4) | 29 (43.9) | |

Results

Of 484 physicians surveyed, 266 (55.0%) returned completed questionnaires, with a 49.4% response rate among trainees (196 of 397 trainees) and an 80.5% response rate among attending physicians (70 of 87 attending physicians). Respondents were mostly trainees (196 of 266 respondents; 73.7%), and 71.4% (190 of 266 respondents) were from university-affiliated hospitals. Results indicated that reporting of diagnostic errors is not uniformly taught, with 20.5% (53 of 259 respondents) reporting that they were never taught about reporting of diagnostic errors, 52.5% (136 of 259 respondents) reporting that they were taught about reporting of diagnostic errors in medical school, and 49.8% (129 of 259 respondents) reporting that they were taught about reporting of diagnostic errors in residency (Figure). Most respondents indicated that, when diagnostic errors occurred, errors were addressed by informal feedback with a team member (104 of 253 respondents; 41.1%). Other avenues of reporting included formal group discussion (eg, morbidity and mortality conference) (92 of 253 respondents; 36.4%) and formal feedback with a team member (35 of 253 respondents; 13.8%); some respondents reported that diagnostic errors were not addressed (22 of 253 respondents; 8.7%). The most common options for reporting diagnostic errors by trainees were to report errors to attending physicians (158 of 254 respondents; 62.2%), to report errors to senior residents (141 of 255 respondents; 55.3%), and to use anonymous reporting systems (137 of 254 respondents; 53.9%).

Many physicians (104 of 254 respondents; 40.9%) felt uncomfortable or very uncomfortable with reporting diagnostic errors. Nearly half of the respondents (107 of 250; 42.8%) disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that their current reporting system was helpful in reducing diagnostic errors.

Subgroup analyses revealed differences between the responses given by residents and attending physicians (Table). Trainees were more likely than attending physicians to feel uncomfortable or very uncomfortable reporting diagnostic errors (44.6% vs 30.9%, 2-tailed P = .05) and were less likely to say that diagnostic errors should be reported to an attending physician (56.2% vs 79.1%, P = .001).

Discussion

In this large, multicenter study assessing the National Academy of Medicine’s goals on education and reporting among internal medicine physicians, we found inconsistent training on how to communicate diagnostic errors to patients, no unified system for reporting diagnostic errors, a widespread opinion that current reporting systems were unhelpful, and that many respondents were not comfortable with reporting diagnostic errors, especially more junior physicians. Younger physicians might feel particularly uncomfortable with reporting diagnostic errors because of a lack of clinical experience, fear of punitive action, or a lack of confidence in their reporting systems.5,6

Our study may be limited by recall and social desirability bias. We also asked participants to use the National Academy of Medicine definition when describing training or events associated with diagnostic errors, which potentially created a dichotomous variable that might not fully account for the nuances of diagnosis in practice. Our findings suggest that given the significance of diagnostic errors, improving training regarding and comfort with communicating and reporting diagnostic errors is crucial to reduce such errors and improve patient care outcomes.

References

- 1.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rencic J, Trowbridge RL Jr, Fagan M, Szauter K, Durning S. Clinical reasoning education at US medical schools: results from a national survey of internal medicine clerkship directors. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1242-1246. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4159-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trowbridge RL, Dhaliwal G, Cosby KS. Educational agenda for diagnostic error reduction. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(suppl 2):ii28-ii32. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graber ML, Wachter RM, Cassel CK. Bringing diagnosis into the quality and safety equations. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1211-1212. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wachter RM, Pronovost PJ. Balancing “no blame” with accountability in patient safety. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1401-1406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb0903885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kachalia A. Improving patient safety through transparency. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1677-1679. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1303960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]