Abstract

Background

Syncope could be related to high risk of falls and injury in adults, but documentation is sparse. We examined the association between syncope and subsequent fall-related injuries in a nationwide cohort.

Methods

By cross-linkage of nationwide registers, all residents ≥18 years with a first-time diagnosis of syncope were identified between 1997–2012. Syncope patients were matched 1:1 with individuals from the general population. The absolute one-year risk of fall-related injuries, defined as fractures and traumatic head injuries requiring hospitalization, was calculated using Aalen-Johansen estimator. Ratios of the absolute one-year risk of fall-related injuries (ARR) were assessed by absolute risk regression analysis.

Results

We identified 125,763 patients with syncope: median age 65 years (interquartile range 46–78). At one year, follow-up was complete for 99.8% where a total of 8394 (6.7%) patients sustained a fall-related injury requiring hospitalization, of which 1606 (19.1%) suffered hip fracture. In the reference group, 4049 (3.2%) persons had a fall-related injury. The one-year ARR of a fall-related injury was 1.79 (95% confidence interval 1.72–1.87, P<0.001) in patients with syncope compared with the reference group; however, increased ARR was not exclusively in older patients. Factors independently associated with increased ARR of fall-related injuries in the syncope population were: injury in past 12 months, 2.39 (2.26–2.53, P<0.001), injury in relation to the syncope episode, 1.62 (1.49–1.77, P<0.001), and depression, 1.37 (1.30–1.45, P<0.001)

Conclusion

Patients with syncope were at 80% increased risk of severe fall-related injuries within the year following discharge. Notably, increased risk was not exclusively in older patients.

Introduction

Syncope episodes are frequent in both young and older adults, [1–3] and characterized by a total loss of consciousness due to transiently reduced cerebral blood flow with subsequent complete recovery. [4, 5] Nonetheless, episodes do often lead to falls, and syncope could be related to an increased risk of injuries. Falls and fall-related complications are a considerable public health concern in terms of morbidity, mortality, quality of life, and cost of health and social services, especially among older adults. [6–10]

Over the last decade, the overlap in symptoms of syncope and falls, particularly in older persons, has received growing attention. [11–13] A number of age-related factors (physiological and pathological), in combination with amnesia for loss of consciousness, and lack of a witness account, may confound the assessment of syncope. [14] Consequently, persons with syncope are likely to present with an unexplained fall rather than syncope. [15, 16] Moreover, several studies have observed high prevalence of cardiovascular conditions among older persons presenting with unexplained falls. [17] Some of these conditions, particularly carotid sinus syndrome and orthostatic hypotension, are observed risk factors for unexplained falls and fall injuries, and also important causes of syncope in the elderly. [18–21] Yet, evidence on the associations between syncope syndromes and falls or injuries is sparse and mainly based on cross-sectional studies in selected settings. One study among approximately 200 elderly patients with syncope reported a two-year incidence of fractures of 11%, but injury was a secondary outcome and further analysis was not undertaken. [22] Moreover, previous studies among adult patients with syncope report that 26% to 39% suffer from injuries in relation to their syncope episode, [23, 24] but whether this is exclusively in older adults is unknown.

We conducted a nationwide study of adult patients with a first-time diagnosis of syncope, to provide longitudinal population-based data on the association between syncope and subsequent fall-related injuries. Our objectives were to assess the risk of fall-related injuries following syncope and evaluate if physical injury in this population occurs predominantly in older adults, and to compare the risk of fall-related injuries following syncope with that of the general population.

Methods

The study is a nationwide register-based cohort study from January 1, 1997 to December 31, 2013. The study was conducted in Denmark where health services are predominantly tax-funded, which ensures free access to healthcare for the entire population. Individual-level linkage of information between population-based registers is possible due to a unique and personal identification number, which is assigned to each resident at birth or upon immigration. [25]

Registers

The Civil Registration System holds information on the date of birth, death, sex, and migration for all residents. [25] Data on medical history and outcomes were retrieved from discharge diagnoses and claimed prescriptions as appropriate. The Danish National Patient Register holds data on all hospitalizations since 1977. [26] At discharge, each hospital contact is registered with one principal diagnosis, and if appropriate, one or several supplementary diagnoses according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). The Danish Register of Medicinal Product Statistics comprises information about claimed prescriptions, and each drug dispensing is registered according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system. [27] Partial reimbursement of drug expenses by the national healthcare system ensures complete registration by the pharmacies. Average five-year household income prior to study start served as a proxy of socioeconomic status, and information was obtained from Statistics Denmark. [28]

Study population

The study population comprised all residents ≥18 years with a first-time primary discharge diagnosis of syncope between 1997 and 2012. Both inpatient and emergency department (ED) encounters were included. Subjects with prior syncope outpatient contacts were excluded. The reference group was obtained with risk set matching: Each subject in the syncope population was matched with one subject from the general population without prior syncope hospitalizations by year of birth and sex. The ICD diagnosis of syncope (10th revision code R55.9) refers to the most common etiologies of syncope, [5] and has previously been validated with a positive predictive value of 96%.[29]

Covariates

Potential confounding factors were pre-specified and identification was based on current knowledge in combination with the construction of a model diagram. [30] The following medical variables were considered: cardiovascular disease (including ischemic heart disease or myocardial infarction, heart failure, cardiac arrhythmia, atrioventricular block or left bundle branch block, cerebral vascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease), pacemaker, diabetes mellitus, cancer, dementia, depression, Parkinson disease, and use of loop diuretic, antihypertensive, or anxiolytic drugs. Information was retrieved from diagnosis or surgical procedure codes up to ten years prior to inclusion, and from claimed prescriptions up to one year prior to inclusion (S1 Table). We considered combination treatment with at least two standard antihypertensive agents within a period of 90 days as use of antihypertensive drugs. [31] When appropriate, we combined diagnosis and prescription data of comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, depression, and dementia, to increase the sensitivity of the covariates. Osteoporosis is a main risk factor of fragility-fractures, but because the association with syncope is unclear, it was not considered a principal confounder.

Study outcome

The primary outcome of a fall-related injury was defined as any hospital encounter (ED visit or inpatient admission) from fractures (femur, pelvis, shoulder or upper arm, elbow, forearm or wrist, and skull) or traumatic head injuries (S1 Table). The approach has been used previously as a proxy for serious falls. [9] The outcome of interest was post-discharge injuries, so documentation of an injury in relation to the syncope episode was not considered as an event (but evaluated in supplementary analyses). The study population was followed for one year, or until the occurrence of a fall-related injury, emigration, or death.

Statistics

Differences in baseline characteristics were compared using chi-squared test for categorical variables. We report loss to follow-up at one year. The level of significance was set at 5%. To assess the time-dependent absolute risk of fall-related injuries following syncope, we used the Aalen-Johansen estimator to account for the competing risk of death. [32] Furthermore, we report one-year risks separately for the syncope and reference group and according to age at baseline. The relation between the absolute risks and age (continuous scale) was obtained with the Aalen-Johansen estimate and kernel smoothing.

In our main analysis, we performed absolute risk regression analysis, [33] and report absolute risk ratios (ARR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) referring to the probability of sustaining a fall-related injury during the next year for persons with syncope compared to persons without syncope, given fixed values for the other predictor variables. Models were adjusted for age (five-year intervals), sex, calendar year (four-year intervals), and socioeconomic status in addition to comorbidities and pharmacotherapies. Effect modification was analyzed in subgroups defined by clinical relevance, thus the syncope-associated one-year risks of fall-related injuries were estimated in subgroups defined by age, sex, cardiovascular disease, arrhythmia, pacemaker, loop diuretic use, depression, and fall-related injury in the past 12 months. We further analyzed absolute risk ratios to associate changes in one-year risk of fall-related injuries with differences in person characteristics in the syncope population.

Sensitivity analyses adjusted for osteoporosis and prior fall-related injury respectively, and in another analysis, we excluded all patients with fall-related injury in relation to the syncope episode. We also examined whether the risk was similar for patients with syncope who were admitted to hospital and patients discharged from the ED. All analyses were repeated with hip fracture as the outcome of interest; specifically, because hip fractures are both highly correlated with falls, and require hospitalization. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Gary, NC, USA) and R version 3.4. [34]

Ethics

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (ref. number: 2007-58-0015 / GEH-2014-013 I-Suite number: 02731). In Denmark, ethical approval is not required for retrospective register-based studies. All analyses were executed on servers placed at Statistics Denmark.

Results

In the period from 1997 through 2012, 125,763 adult patients with a first-time diagnosis for syncope were identified (n = 8288 were excluded due to prior syncope outpatient contacts), of which 68,671 (54.6%) represented inpatient admissions. The median age of patients with syncope was 65 years (interquartile range [IQR] 46–78) and 65,608 (52.2%) were women (Table 1). The most prevalent comorbidities were ischemic heart disease (n = 20,093, 16.0%), arrhythmia (n = 15,673, 12.5%), and depression (n = 22,415, 17.8%). Prevalence of comorbidities was greater in the syncope population compared with the matched reference group, as was the frequency of a prior fall-related injury (n = 7912, 6.3% versus n = 3774, 3.0%, P<0.001).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study populationa, b.

| Syncope (n = 125,763) | No syncope (n = 125,763) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median [IQR], years | 65 [46–78] | 65 [46–78] |

| Age groups, years | ||

| 18–49 | 35,213 (28.0) | 35,213 (28.0) |

| 50–64 | 26,292 (20.9) | 26,292 (20.9) |

| 65–79 | 36,153 (28.7) | 36,153 (28.7) |

| ≥80 | 28,105 (22.3) | 28,105 (22.3) |

| Women | 65,608 (52.2) | 65,608 (52.2) |

| Men | 60,155 (47.8) | 60,155 (47.8) |

| Income groupc, quartiles | ||

| <First quartile | 24,933 (19.8) | 25,372 (20.2) |

| First to third quartile | 78,049 (62.1) | 72,867 (57.9) |

| >Third quartile | 22,781 (18.1) | 27,524 (21.9) |

| Comorbidity | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 40,659 (32.3) | 20,031 (15.9) |

| Ischemic heart disease or MI | 20,093 (16.0) | 9428 (7.5) |

| Heart failure | 9053 (7.2) | 4033 (3.2) |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 15,673 (12.5) | 6679 (5.3) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 11,688 (9.3) | 5339 (4.2) |

| AV block or LBBB | 2576 (2.0) | 691 (0.5) |

| Cerebral vascular disease | 12,875 (10.2) | 5755 (4.6) |

| Pacemaker | 3700 (2.9) | 937 (0.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10,500 (8.3) | 7123 (5.7) |

| Cancer | 10,378 (8.3) | 7953 (6.3) |

| Depression | 22,415 (17.8) | 12,806 (10.2) |

| Parkinson disease | 2760 (2.2) | 1499 (1.2) |

| Dementia | 3981 (3.2) | 2097 (1.7) |

| Osteoporosis | 5892 (4.7) | 4779 (3.8) |

| Pharmacotherapy | ||

| Antihypertensive drugs | 37,865 (30.1) | 25,480 (20.3) |

| Loop diuretic drugs | 17,910 (14.2) | 11,330 (9.0) |

| Anxiolytic drugs | 27,041 (21.5) | 18,332 (14.6) |

| Fall-injury in past 12 m | 7912 (6.3) | 3774 (3.0) |

| Syncope inpatient admission | 68,671 (54.6) | NA |

| Syncope ED visit | 57,092 (45.4) | NA |

| Syncope and injuryd | 4601 (3.7) | NA |

| Year of inclusion | ||

| 1997–2000 | 29,776 (23.7) | 29,776 (23.7) |

| 2001–2004 | 32,640 (26.0) | 32,640 (26.0) |

| 2005–2008 | 31,171 (24.8) | 31,171 (24.8) |

| 2009–2012 | 32,176 (25.6) | 32,176 (25.6) |

Abbreviations: IQR (interquartile range), MI (myocardial infarction), LBBB (left bundle branch block), ED (emergency department), NA (not applicable)

aData are expressed as no. (%) unless otherwise indicated

bP values were <0.001 (except for age and sex)

cAverage five-year household income prior to inclusion

dDocumented fall-related injury in relation to the syncope episode

Absolute one-year risk of fall-related injuries following syncope

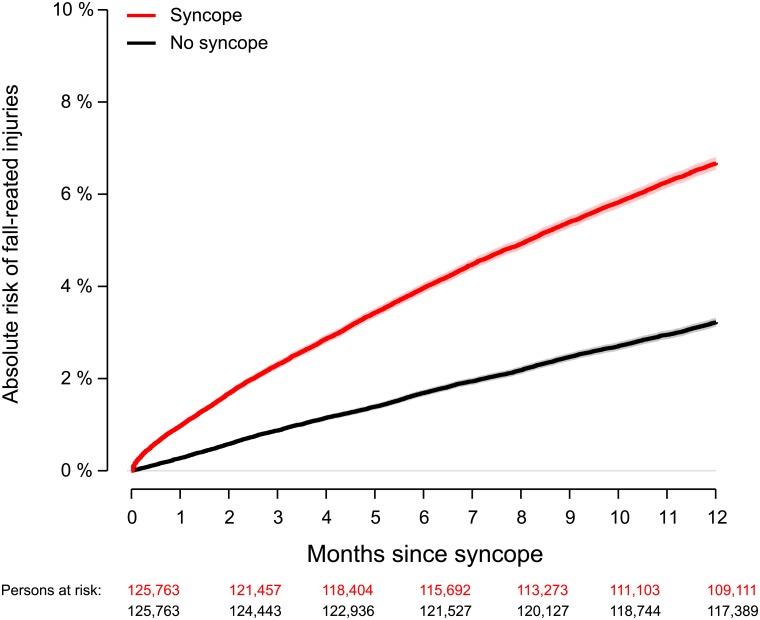

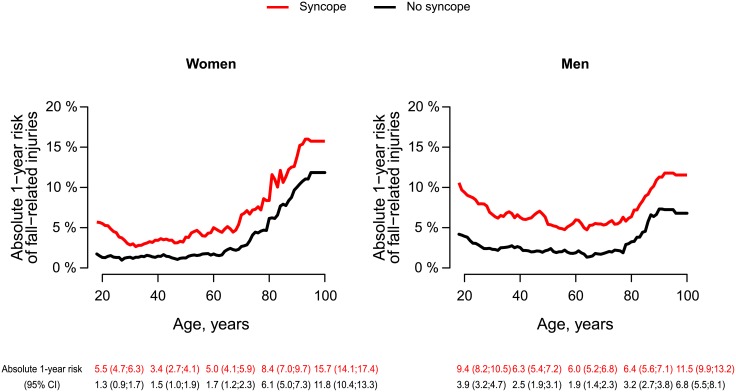

At one year, follow-up was complete for 99.8% of the syncope population (n = 199, 0.2% emigrated). A total of 8394 (6.7%, 95% CI, 6.6%-6.8%) patients had a fall-related injury requiring re-hospitalization, whereas 4049 (3.2%, 95% CI, 3.1%-3.3%) persons in the reference group had a fall-related injury (Fig 1). Hip fracture accounted for one out of five injury hospitalizations among persons with syncope (n = 1606, 19.1%) compared with n = 1016 in the reference group (S2 Table). Fig 2 shows the absolute one-year risks of fall-related injuries according to age in the syncope and reference population respectively. The absolute risk of a fall-related injury increased with advancing age, and was particularly high among elderly women; however, young men did also have a substantial risk of injury.

Fig 1. Absolute risk of hospitalization due to fall-related injuries following syncope.

Syncope population (red), matched reference group (black). One-year absolute risk of fall-related injuries was 6.7% (95% CI, 6.5%-6.8%) in the syncope population, and 3.2% (95% CI, 3.1%-3.3%) in the age- and sex matched reference group.

Fig 2. Absolute one-year risks of fall-related injuries according to age.

Absolute one-year risks of fall-related injuries according to age at syncope accounting for the competing risk of death in the syncope (red) and matched reference population (black) respectively. Selected point estimates with 95% CI are shown.

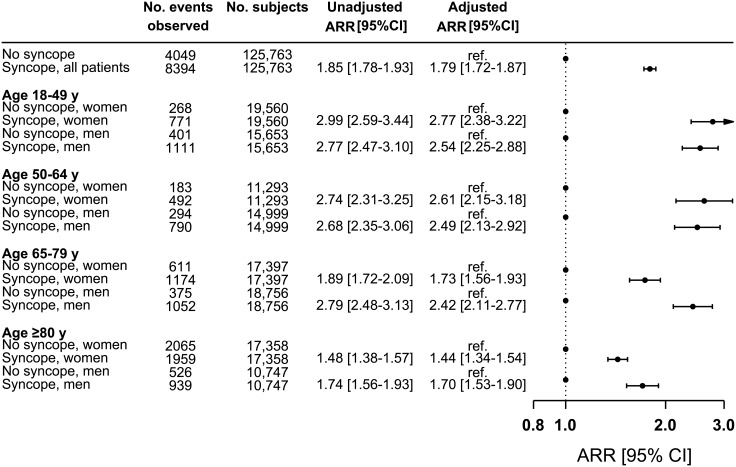

Risk of fall-related injuries in patients with syncope compared to persons without syncope

The one-year adjusted ARR of fall-related injuries was 1.79 (95% CI, 1.72–1.87, P<0.001) in patients with syncope compared with the reference group (unadjusted ARR, 1.85, 95% CI, 1.78–1.93, P<0.001). Fig 3 presents risk estimates stratified by age and sex. We found that the ARR decreased with advancing age. Also, in the older age groups, the relative importance of syncope was greater in men (65–79 years: ARR, 2.42, 95% CI, 2.11–2.77) compared with women (65–79 years: ARR, 1.73, 95% CI, 1.56–1.93). S1 Fig provides a summary of subgroup analyses. The syncope-associated one-year risks of fall-related injuries were increased across subgroups, with the exception of patients with pacemaker (ARR, 1.19, 95% CI, 0.89–1.59, P = 0.23) versus no pacemaker (ARR, 1.81, 95% CI, 1.73–1.88, P<0.001).

Fig 3. One-year absolute risk ratios of fall-related injuries in the syncope population compared with the reference.

The matched group without prior syncope served as reference within each stratum. Multiple absolute risk regression analyses with adjustment for: age, sex, socioeconomic status, calendar year, ischemic heart disease, arrhythmia, atrioventricular block or left bundle branch block, pacemaker, use of antihypertensive, loop diuretic or anxiolytic drugs, depression, diabetes, cancer, Parkinson disease, and dementia. Number of events refers to observed events within one year. ARR indicates absolute risk ratio.

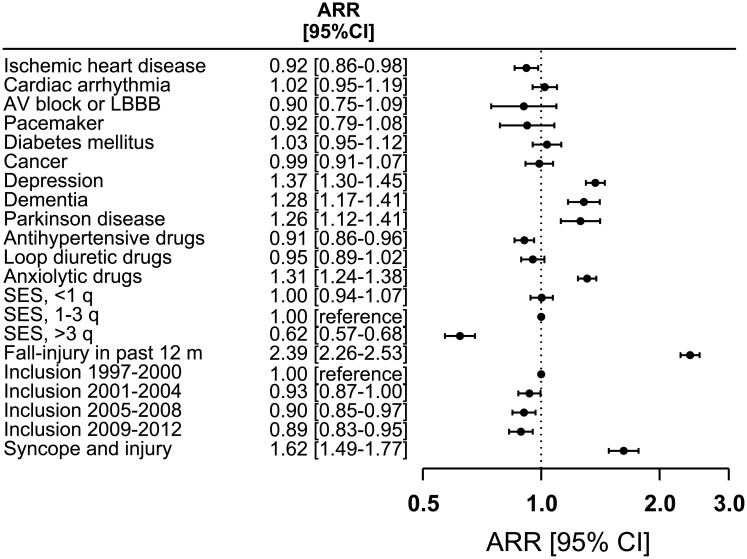

Characteristics associated with one-year risk of fall-related injuries

The three factors most associated with increased ARR of fall-related injuries in the syncope population were: fall-related injury in past 12 months (2.39, 95% CI, 2.26–2.53, P<0.001), fall-related injury in relation to the syncope episode (1.62, 95% CI, 1.49–1.77, P<0.001), and depression (1.37, 95% CI, 1.30–1.45, P<0.001), whereas high socioeconomic status, and use of antihypertensive drugs were associated with decreased one-year risk of fall-related injuries (Fig 4).

Fig 4. Person characteristics associated with one-year absolute risk ratios of fall-related injuries in the syncope population.

Multiple absolute risk regression analysis was done to associate changes in one-year risks of subsequent fall-related injuries with person characteristics. ARR indicates absolute risk ratio, LBBB left bundle branch block, and SES socioeconomic status. Syncope and injury refers to a documented injury in relation to the syncopal event.

Sensitivity analyses

The syncope-associated one-year risk of fall-related injuries was similar for patients seen in the ED (ARR, 1.84, 95% CI, 1.72–1.96, P<0.001) and patients admitted to hospital (ARR, 1.77, 95% CI, 1.68–1.87, P<0.001). Adjustment for osteoporosis did not challenge the results from the main analysis (ARR, 1.79, 95% CI, 1.72–1.86, P<0.001), neither did adjustment for prior fall-related injury (ARR, 1.72, 95% CI, 1.65–1.80, P<0.001), or exclusion of patients with fall-related injury in relation to their syncope episode (ARR, 1.74, 95% CI, 1.67–1.81, P<0.001). Moreover, the main analysis was repeated with hip fracture as outcome, but yielded similar results among subjects’ ≥65 years (the analysis could not be executed in younger subjects due to a limited number of events), S2 Fig.

Discussion

The main finding of the study was that first-time syncope was associated with 80% increased one-year risk of fall-related injuries, in terms of fractures and traumatic head injuries requiring hospitalization, compared with an age- and sex matched reference group. The study is the first to provide comprehensive longitudinal data on injury risk in a real-world clinical setting of adult patients with syncope. Although the absolute risk increased with advancing age, the relative risk of fall-related injuries associated with syncope decreased in the elderly. Plausibly, because multiple factors influence fall-injury risk in older persons the attributable risk associated with syncope decreases with advancing age. Notably, increased risk of injury was not exclusively in older patients, but also substantially increased in young adults with syncope. Depression, prior fall-related injury, and injury in relation to the syncope episode were important risk factors associated with increased risk of sustaining a fall-related injury.

Our observation of increasing absolute risk of fall-related injuries with advancing age, particularly in older women is in line with current knowledge. [9, 35, 36] Medical conditions and physiological changes associated with aging such as impairment in cognition and declines in balance, gait, and muscle strength, contribute to an increased likelihood of falls amongst older adults. [36, 37] In addition, bone fragility such as osteoporosis increases susceptibility to serious injury. [38] Both sarcopenia (age-associated loss of skeletal muscle mass and function) and bone fragility accelerates in association with menopause-related estrogen-deficiency, [39] which could explain the difference in relative risk observed between men and women with syncope in the older age groups.

Although the majority of injuries were observed in the elderly population, younger patients with a history of syncope also had markedly increased risk of injury. However, the injury mechanism is liable to be different in younger and older adults, and while the injuries identified in the current study are strongly related to falls in older adults, [40] other causes may predominate in younger adults such as transportation, work, and sport or leisure activities.[35] Information pertaining to the specific circumstances of the sustained injuries was unavailable in the current study.

Our findings are in keeping with prior research on the association of some individual causes of syncope and unexplained falls and fall injuries in older persons.[18,19,21,41] One study observed that amongst older persons with dementia, roughly 50% of individuals initially referred for an unexplained fall was eventually diagnosed with syncope, with orthostatic hypotension as the most common cause.[42] Similarly, it has been reported that prevalence of CSS is common in older persons referred to ambulatory management for unexplained falls, ranging from 14% to 27%.[20,41,43] Comparisons of our risk estimates regarding the effect of syncope with previous studies remain difficult due to substantial differences in study design, setting, and demographics of the study population.

With advancing age, the attributable risk of cardiac causes of syncope increases. We observed that in patients with a cardiac pacemaker, syncope was not significantly associated with risk of subsequent fall-related injuries. This is in line with a study, which demonstrated a substantial reduction in the number of injurious events amongst individuals with cardio-inhibitory carotid sinus hypersensitivity randomized to pacing.[44] However, conflicting results have been observed for effects of pacing intervention on fall-rates.[45] Furthermore, atrial fibrillation has been associated with syncope and falls.[46, 47] In one study among older adults presenting with unexplained falls, 71% had an incident cardiac arrhythmia within less than a year using an implantable loop recorder, and in 20% a recurrent fall and/or syncope was directly attributable to the arrhythmia. [48] In contrast with these observations, we demonstrated that the syncope-associated risk of fall-related injuries was relatively lower among persons with pre-existing arrhythmias and cardiovascular disease in general. However, register-based data could be subject to ascertainment bias i.e. the probability of receiving a specific cardiac diagnosis over a non-specific syncope diagnosis could be increased in more grievous cases.

Although a single cause is evident in a minority of falls, a multitude of factors, such as environmental factors, acute and chronic medical conditions, and medications are likely to influence the risk of falling. [36, 49] Medications with orthostatic effects, such as antihypertensive, diuretic, and psychotropic drugs, have repeatedly been associated with both syncope and falls. [50–52] In contrast, we observed that use of antihypertensive and loop diuretic drugs was not associated with increased risk in patients with syncope; however, dose changes were not accounted for and could be a possible explanation. Moreover, the additive effects of multiple present risk factors were out of the scope of the current study. In one study, [37] the probability of (recurrent) falls increased from 3% amongst persons with no documented risk factors to 84% among persons with five or more risk factors indicating that modifying even a few factors may reduce the risk of fall-related injuries. Cardiovascular assessment is fundamental in the evaluation of patients with syncope, but perhaps a more extensive assessment is required in some patients. Our results demonstrating that depression, use of anxiolytic drugs, dementia, and prior injury were associated with subsequent re-hospitalization due to fall-related injuries could plausibly indicate that a more multifactorial and interdisciplinary approach needs to be considered in the elderly and patients with multimorbidity.[4, 53, 54] Establishment of formal syncope management facilities could be one way to ensure standardized and appropriate management of patients with syncope, despite the heterogeneous patient group composition, but further research is required. [55]

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study was the use of nationwide registers that enabled identification and complete follow-up of a large cohort of patients with syncope irrespective of age, morbidity, socioeconomic status, and health insurance schemes, and with independent data collection of outcomes. However, the study has several potential limitations. First, due to the observational design, direct conclusions on causal relationships of our findings remain unviable. Second, important clinical parameters including blood pressure, electrocardiographic, echocardiographic or carotid sinus massage findings were unavailable in the registries, so despite extensive adjustments for potential confounding factors, we cannot exclude effects of residual confounding. Furthermore, the ICD registration does not specify the etiologies of syncope; consequently, we do not address effect measures attributable to specific causes of syncope. Instead, we have evaluated subgroups, mainly within different cardiovascular conditions. Third, we cannot exclude the possibility that persons who contact the ED or hospital due to syncope may be inherently different from those who do not; however, effect measures of hip fracture, which should always lead to hospitalization, supported the main results. Of note, the reported risk of fall-related injuries only reflects the number of injury events coming to acute medical attention at EDs and hospitals, and may, therefore, represent an underestimate of total fall-related events. Information pertaining to fatal fall incidents resulting in immediate death prior to hospitalization was unavailable.

Conclusions

In this nationwide study, adult patients with first-time syncope were at 80% increased risk of severe fall-related injuries within the year following discharge. Notably, increased risk was not exclusively in older patients. These findings underscore the necessity of increased clinical awareness about traumatic injury risk and appropriate management of patients with syncope of all ages in clinical practice, and support increased multidisciplinary assessment in falls-prevention among older adults. Further cohort and intervention studies will be needed to reveal causal effects and efficacy of preventive strategies.

Supporting information

(PDF)

(PDF)

The age- and sex matched group without prior syncope served as reference in all analyses. Multiple absolute risk regression analyses with adjustment for: age, sex, calendar year, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and pharmacotherapy. ARR indicates absolute risk ratio.

(PDF)

The age- and sex matched group ≥65 years served as reference. Multiple absolute risk regression analyses with adjustment for: age, sex, calendar year, socioeconomic status, ischemic heart disease, arrhythmia, atrioventricular block or left bundle branch block, pacemaker, use of antihypertensive, loop diuretic or anxiolytic drugs, depression, diabetes, cancer, Parkinson disease, and dementia. ARR for total fall-related injury is provided for comparative purpose. ARR indicates absolute risk ratio.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

Previous presentations: Parts of the results of this study was presented at the European Society of Cardiology Scientific Congress; August 26 to 30, 2017; Barcelona, Spain.

Data Availability

Due to legal restrictions pertaining to use of Danish register-based data, these de-identified data are available only upon request from Statistics Denmark (https://www.dst.dk/en/OmDS/organisation/TelefonbogOrg?kontor=13&tlfbogsort=sektion), provided that relevant ethical and legal permissions have been obtained, and that the researchers meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by a research grant from Lundbeckfonden (grant no. R108-A10415). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ganzeboom KS, Mairuhu G, Reitsma JB, Linzer M, Wieling W, van Dijk N. Lifetime cumulative incidence of syncope in the general population: a study of 549 Dutch subjects aged 35–60 years. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17: 1172–1176. 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00595.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruwald MH, Hansen ML, Lamberts M, Hansen CM, Højgaard MV, Køber L, et al. The relation between age, sex, comorbidity, and pharmacotherapy and the risk of syncope: a Danish nationwide study. Europace. 2012;14: 1506–1514. 10.1093/europace/eus154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, Chen MH, Chen L, Benjamin EJ, et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med. 2002;347: 878–885. 10.1056/NEJMoa012407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen W-K, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, Cohen MI, Forman DE, Goldberger ZD, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70: e39–e110. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brignole M, Moya A, de Lange FJ, Deharo J-C, Elliott PM, Fanciulli A, et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope. Eur Heart J. 2018;39: 1883–1948. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. WHO global report on falls prevention in older age [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Falls_prevention7March.pdf

- 7.Tinetti ME, Williams CS. Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med. 1997;337: 1279–1284. 10.1056/NEJM199710303371806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kannus P, Parkkari J, Koskinen S, Niemi S, Palvanen M, Järvinen M, et al. Fall-Induced Injuries and Deaths Among Older Adults. JAMA. 1999;281: 1895–1899. 10.1001/jama.281.20.1895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartholt KA, van Beeck EF, Polinder S, van der Velde N, van Lieshout EMM, Panneman MJM, et al. Societal consequences of falls in the older population: injuries, healthcare costs, and long-term reduced quality of life. J Trauma. 2011;71: 748–753. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f6f5e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scuffham P, Chaplin S, Legood R. Incidence and costs of unintentional falls in older people in the United Kingdom. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57: 740–744. 10.1136/jech.57.9.740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Kidd S. Forgetting falls. The limited accuracy of recall of falls in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36: 613–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies AJ, Kenny RA. Falls presenting to the accident and emergency department: types of presentation and risk factor profile. Age Ageing. 1996;25: 362–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McIntosh S, Da Costa D, Kenny RA. Outcome of an integrated approach to the investigation of dizziness, falls and syncope in elderly patients referred to a “syncope” clinic. Age Ageing. 1993;22: 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenny RA. Syncope in the elderly: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14: S74–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parry SW, Steen IN, Baptist M, Kenny RA. Amnesia for loss of consciousness in carotid sinus syndrome: implications for presentation with falls. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45: 1840–1843. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Dwyer C, Bennett K, Langan Y, Fan CW, Kenny RA. Amnesia for loss of consciousness is common in vasovagal syncope. Europace. 2011;13: 1040–1045. 10.1093/europace/eur069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jansen S, Bhangu J, de Rooij S, Daams J, Kenny RA, van der Velde N. The Association of Cardiovascular Disorders and Falls: A Systematic Review. J Am Med. 2016;17: 193–199. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menant JC, Wong AKW, Trollor JN, Close JCT, Lord SR. Depressive Symptoms and Orthostatic Hypotension Are Risk Factors for Unexplained Falls in Community-Living Older People. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64: 1073–1078. 10.1111/jgs.14104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamrefors V, Härstedt M, Holmberg A, Rogmark C, Sutton R, Melander O, et al. Orthostatic Hypotension and Elevated Resting Heart Rate Predict Low-Energy Fractures in the Population: The Malmö Preventive Project. PloS One. 2016;11: e0154249 10.1371/journal.pone.0154249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies AJ, Steen N, Kenny RA. Carotid sinus hypersensitivity is common in older patients presenting to an accident and emergency department with unexplained falls. Age Ageing. 2001;30: 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anpalahan M, Gibson S. The prevalence of Neurally Mediated Syncope in older patients presenting with unexplained falls. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23: e48–52. 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ungar A, Galizia G, Morrione A, Mussi C, Noro G, Ghirelli L, et al. Two-year morbidity and mortality in elderly patients with syncope. Age Ageing. 2011;40: 696–702. 10.1093/ageing/afr109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Disertori M, Brignole M, Menozzi C, Raviele A, Rizzon P, Santini M, et al. Management of patients with syncope referred urgently to general hospitals. Europace. 2003;5: 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brignole M, Ungar A, Bartoletti A, Ponassi I, Lagi A, Mussi C, et al. Standardized-care pathway vs. usual management of syncope patients presenting as emergencies at general hospitals. Europace. 2006;8: 644–650. 10.1093/europace/eul071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29: 541–549. 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015; 449 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallach Kildemoes H, Toft Sorensen H, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39: 38–41. 10.1177/1403494810394717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J. Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39: 103–105. 10.1177/1403494811405098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruwald MH, Hansen ML, Lamberts M, Kristensen SL, Wissenberg M, Olsen A-MS, et al. Accuracy of the ICD-10 discharge diagnosis for syncope. Europace. 2013;15: 595–600. 10.1093/europace/eus359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10: 37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olesen JB, Lip GYH, Hansen ML, Hansen PR, Tolstrup JS, Lindhardsen J, et al. Validation of risk stratification schemes for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation: nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2011;342: d124 10.1136/bmj.d124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersen PK, Geskus RB, de Witte T, Putter H. Competing risks in epidemiology: possibilities and pitfalls. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41: 861–870. 10.1093/ije/dyr213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerds TA, Scheike TH, Andersen PK. Absolute risk regression for competing risks: interpretation, link functions, and prediction. Stat Med. 2012;31: 3921–3930. 10.1002/sim.5459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Internet]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 35.Høidrup S, Sørensen TIA, Grønbaek M, Schroll M. Incidence and characteristics of falls leading to hospital treatment: a one-year population surveillance study of the Danish population aged 45 years and over. Scand J Public Health. 2003;31: 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F, Foschi R, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2010;21: 658–668. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graafmans WC, Ooms ME, Hofstee HM, Bezemer PD, Bouter LM, Lips P. Falls in the elderly: a prospective study of risk factors and risk profiles. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143: 1129–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Schneider SM, Zúñiga C, Arai H, Boirie Y, et al. Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: a systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing. 2014;43: 748–759. 10.1093/ageing/afu115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seeman E. Pathogenesis of bone fragility in women and men. Lancet. 2002;359: 1841–1850. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08706-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costa AG, Wyman A, Siris ES, Watts NB, Silverman S, Saag KG, et al. When, where and how osteoporosis-associated fractures occur: an analysis from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). PloS One. 2013;8: e83306 10.1371/journal.pone.0083306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar NP, Thomas A, Mudd P, Morris RO, Masud T. The usefulness of carotid sinus massage in different patient groups. Age Ageing. 2003;32: 666–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ungar A, Mussi C, Ceccofiglio A, Bellelli G, Nicosia F, Bo M, et al. Etiology of Syncope and Unexplained Falls in Elderly Adults with Dementia: Syncope and Dementia (SYD) Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64: 1567–1573. 10.1111/jgs.14225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rafanelli M, Ruffolo E, Chisciotti VM, Brunetti MA, Ceccofiglio A, Tesi F, et al. Clinical aspects and diagnostic relevance of neuroautonomic evaluation in patients with unexplained falls. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2014;26: 33–37. 10.1007/s40520-013-0124-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kenny RA, Richardson DA, Steen N, Bexton RS, Shaw FE, Bond J. Carotid sinus syndrome: a modifiable risk factor for nonaccidental falls in older adults (SAFE PACE). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38: 1491–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parry SW, Steen N, Bexton RS, Tynan M, Kenny RA. Pacing in elderly recurrent fallers with carotid sinus hypersensitivity: a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled crossover trial. Heart. 2009;95: 405–409. 10.1136/hrt.2008.153189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanders NA, Ganguly JA, Jetter TL, Daccarett M, Wasmund SL, Brignole M, et al. Atrial fibrillation: an independent risk factor for nonaccidental falls in older patients. PACE. 2012;35: 973–979. 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2012.03443.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jansen S, Frewen J, Finucane C, de Rooij SE, van der Velde N, Kenny RA. AF is associated with self-reported syncope and falls in a general population cohort. Age Ageing. 2015;44: 598–603. 10.1093/ageing/afv017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhangu J, McMahon CG, Hall P, Bennett K, Rice C, Crean P, et al. Long-term cardiac monitoring in older adults with unexplained falls and syncope. Heart. 2016; 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lawlor DA, Patel R, Ebrahim S. Association between falls in elderly women and chronic diseases and drug use: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2003;327: 712–717. 10.1136/bmj.327.7417.712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tinetti ME, Han L, Lee DSH, McAvay GJ, Peduzzi P, Gross CP, et al. Antihypertensive medications and serious fall injuries in a nationally representative sample of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174: 588–595. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Torstensson M, Hansen AH, Leth-Møller K, Jørgensen TSH, Sahlberg M, Andersson C, et al. Danish register-based study on the association between specific cardiovascular drugs and fragility fractures. BMJ Open. 2015;5: e009522 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, Patel B, Marin J, Khan KM, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169: 1952–1960. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Sherrington C, Gates S, Clemson LM, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9: CD007146 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Close J, Ellis M, Hooper R, Glucksman E, Jackson S, Swift C. Prevention of falls in the elderly trial (PROFET): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353: 93–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06119-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kenny RA, Brignole M, Dan G-A, Deharo JC, van Dijk JG, Doherty C, et al. Syncope Unit: rationale and requirement—the European Heart Rhythm Association position statement endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace. 2015;17: 1325–1340. 10.1093/europace/euv115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

(PDF)

The age- and sex matched group without prior syncope served as reference in all analyses. Multiple absolute risk regression analyses with adjustment for: age, sex, calendar year, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and pharmacotherapy. ARR indicates absolute risk ratio.

(PDF)

The age- and sex matched group ≥65 years served as reference. Multiple absolute risk regression analyses with adjustment for: age, sex, calendar year, socioeconomic status, ischemic heart disease, arrhythmia, atrioventricular block or left bundle branch block, pacemaker, use of antihypertensive, loop diuretic or anxiolytic drugs, depression, diabetes, cancer, Parkinson disease, and dementia. ARR for total fall-related injury is provided for comparative purpose. ARR indicates absolute risk ratio.

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

Due to legal restrictions pertaining to use of Danish register-based data, these de-identified data are available only upon request from Statistics Denmark (https://www.dst.dk/en/OmDS/organisation/TelefonbogOrg?kontor=13&tlfbogsort=sektion), provided that relevant ethical and legal permissions have been obtained, and that the researchers meet the criteria for access to confidential data.