Abstract

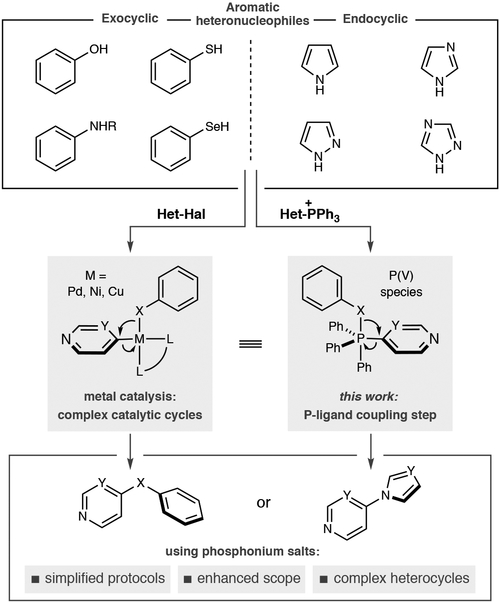

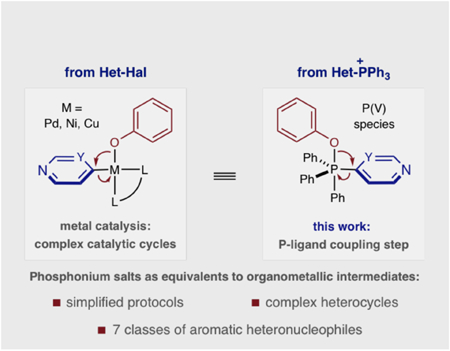

Coupling aromatic heteronucleophiles to arenes is a common way to assemble drug-like molecules. Many methods operate via nucleophiles intercepting organometallic intermediates, via Pd-, Cu- and Ni-catalysis, that facilitate carbon-heteroatom bond-formation and a variety of protocols. We present an alternative, unified strategy where phosphonium salts can replicate the behavior of organometallic intermediates. Under a narrow set of reaction conditions, a variety of aromatic heteronucleophile classes can be coupled to pyridines and diazines that are often problematic in metal-catalyzed couplings, such as where (pseudo)halide precursors are unavailable of in complex structures with multiple polar functional groups.

Keywords: heteroatom coupling, pyridines, phosphonium salts, late-stage, kinase inhibitors

Graphical Abstract

Aromatic heteronucleophiles, such as phenols, thiophenols, anilines, imidazoles and pyrazoles, are frequently coupled to pyridine and diazine heterocycles to make drug-like molecules. Metal catalysts are most commonly used to facilitate this transformation, but the wide variety of reaction protocols and complex catalytic cycles can limit their use for complex heterocycles. We present an alternative approach where seven distinct classes of nucleophiles are coupled to azine phosphonium salts via a nucleophile addition-P-ligand coupling mechanism. A narrow range of reaction conditions and applicability to drug-like fragments as well as complex bioactive molecules are advantages of this approach.

Aromatic heteronucleophiles can be classified as exocyclic, and include phenols, thiophenols and anilines, or endocyclic, such as pyrroles, indoles, imidazoles and pyrazoles. These structures are fundamental building blocks that are routinely coupled to other aromatic compounds to make drug-like molecules. Coupling to pyridines, quinolines and diazines is particularly relevant as they are important pharmacophores and have resulted in several marketed drugs. For example, azine–O–aryl and azine–NR–aryl linkages are present in a large family of kinase inhibitors and include therapeutics such as sorafenib, gleevec and erlotinib.[1,2]

Typical azine coupling stratiegies use SNAr reactions and, most commonly, metal-catalyzed processes; in the latter, aromatic heteronucleophiles intercept organometallic intermediates derived from oxidative addition into heteroaryl (pseudo)halides or transmetalation processes.[3–5] Carbon-heteroatom bond-formation occurs by reductive elimination, but the success of these reactions is dependent on all elementary steps of the complex catalytic cycle. As a result, a multitude of catalytic protocols exist varying in metal, ligand, base and other reaction parameters. We envisioned an alternative, unified strategy where heterocyclic phosphonium salts could serve as equivalents to organometallic intermediates. In this way, carbon-heteroatom bond-formation occurs by a nucleophilic addition then phosphorus ligand-coupling that approximates one subsection of a metal-catalysis cycle.[6] We envisioned that this truncated mechanism would enable multiple distinct nucleophiles to be employed under a narrow set of reaction conditions and simplify access to a range of coupled products.[7] Furthermore, complex azine-containing structures can often be problematic in metal-catalyzed processes because of the limited availability of cross-coupling precursors and the tendency of polar functional groups, often present in these molecules, to interfere with catalytic processes.[8] Herein, we show that this strategy has been successfully executed by coupling seven classes of aromatic heteronucleophiles to a range of pyridine and diazine phosphonium salts.

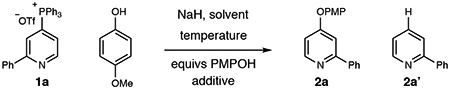

Our laboratory has previously reported that a diverse set of pyridines and diazines can be directly and selectively converted into heterocyclic phosphonium salts from C–H bond precursors.[9] The phosphonium ion then serves as a generic functional handle and enables a range of subsequent bond-forming reactions.[10] Notably, the scope of these reactions significantly expands the range of heterocycles beyond typical functionalization reactions such as halogenation or borylation.[11] While aliphatic heteronucleophiles, such as alkoxides,[9a] are competent coupling partners, we found that aromatic heteronucleophiles were not successful under the same reactions conditions and highlight the challenges of using new classes of coupling partners. As a representative case, Table 1 shows that reacting 2-phenylpyridine phosphonium salt 1a and sodium para-methoxyphenoxide in THF at room temperature does not result in any of the desired aryl-pyridyl ether product 2a (entry 1). Instead, salt 1a partially decomposed to C–H compound 2a’. Adding 15-crown-5 to the reaction resulted in a small amount of the desired product 2a; raising the temperature to 40 °C and changing the equivalents of the nucleophile to 1.5 increased conversion further (entries 2–4). Entry 5 shows that removing 15-crown-5 affects the reaction profile with more C–H product formed. Conducing the reaction at 60 °C is the most effective protocol resulting in in the most favorable ratio of 2a and 2a’ (entry 6). The most significant byproducts of the reaction are triphenylphosphine and triphenyl phosphine oxide that are straightforward to remove by column chromatography. The reaction performs well in DME, whereas 1,4-dioxane is less efficient. Running the reaction in DMF resulted in traces of the desired product 2a and C–H compound 2a’ predominates (entries 7–9). While alkali decomposition of phosphonium salts is known, the mechanism(s) of these processes are not well resolved and are subject to ongoing investigations in our laboratory.[12] Nevertheless, we were confident that this optimization blueprint would also apply to other classes of aromatic heteronucleophiles.

Table 1.

| Entry |

T [°C] |

Solvent | Equiv PMPOH | Additive | Yield [%][b] 2a |

Yield [%][b] 2a’ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23 | THF | 1.1 | none | 0 | 87 |

| 2 | 23 | THF | 1.1 | 15-crown-5 | 3 | 83 |

| 3 | 40 | THF | 1.1 | 15-crown 5 | 36 | 59 |

| 4 | 40 | THF | 1.5 | 15-crown-5 | 49 | 40 |

| 5 | 40 | THF | 1.5 | none | 36 | 62 |

| 6 | 60 | THF | 1.5 | 15-crown-5 | 87 | 6 |

| 7 | 60 | DME | 1.5 | 15-crown-5 | 76 | 21 |

| 8 | 40 | 1,4-dioxane | 1.5 | 15-crown-5 | 14 | 81 |

| 9 | 40 | DMF | 1.5 | none | 1 | 91 |

With 0.2 mmol 1a and equivs of NaH match equivs of para-methoxyphenol.

Yields determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reactions using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard.

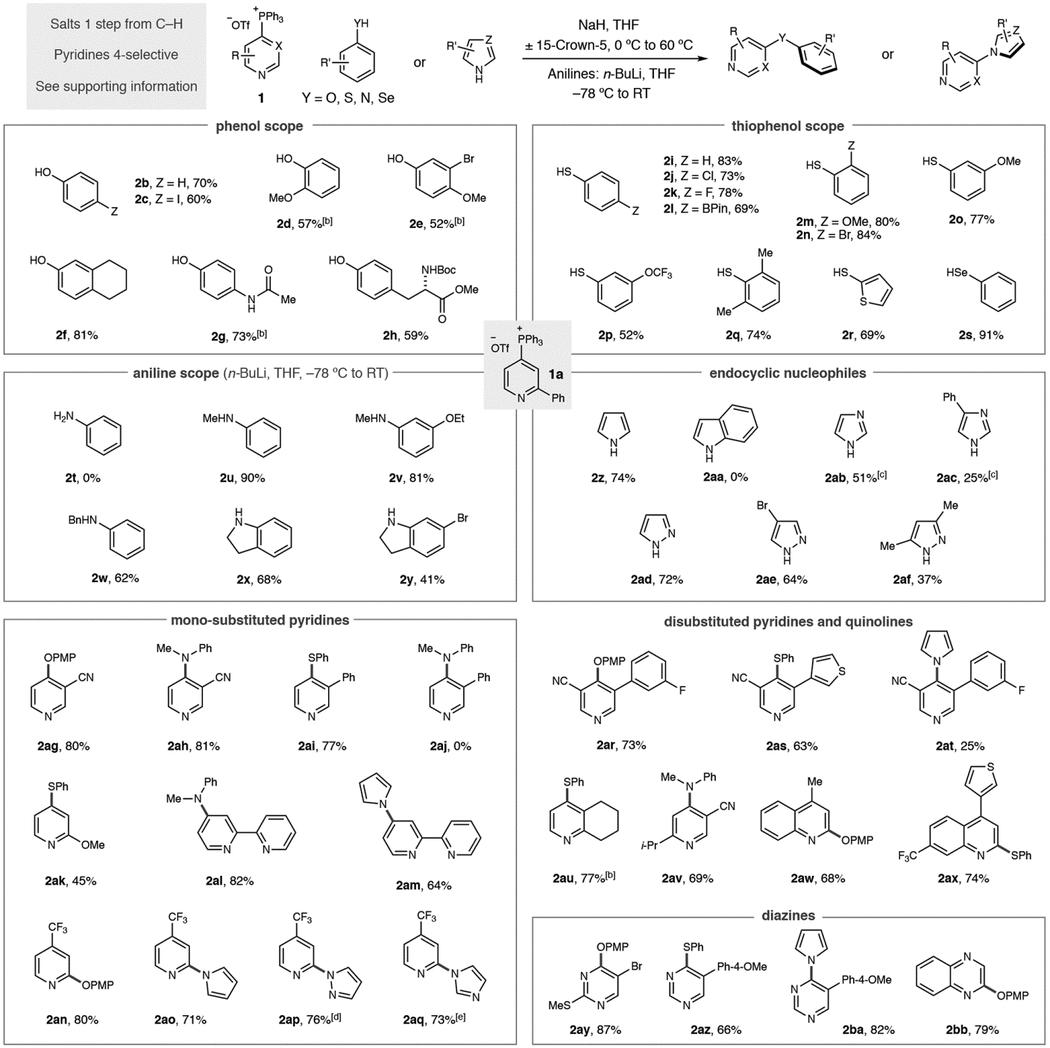

We next examined the scope of different classes of aromatic heteronucleophiles in coupling reactions with 2-phenylpyridine phosphonium salt 1a (Table 2). Phenol and para-iodo phenol are tolerated in this protocol, with the C–I bond in the latter being reactive in transition metal-catalyzed processes (2b and 2c). However, the withdrawing effect of halides reduces the yield of coupled product in the reaction. Substituents in the ortho- and meta-positions of phenols also provide coupled products in reasonable yields (2d–2f). An advantage of this protocol is that pKa effects can be exploited for chemoselective reactions; the phenolic oxygen reacts preferentially in both acetaminophen and a Boc-protected tyrosine (2g and 2h). Thiophenol is a good nucleophile in this process, as are a useful range of ortho-, meta- and para-substituented derivatives (2i–2p). Coupling of hindered nucleophiles is possible, such as the 2,6-disubstituted pattern in 2q. Heteroaromatics, such as thiophenes, can be components of the nucleophile (2r) and selenophenols are also excellent coupling partners (2s). Anilines require a modified reaction protocol; the nucleophile is deprotonated at −78 °C using n-BuLi, the phosphonium salt is added and then the reaction is allowed to warm to room temperature. Importantly, the nitrogen atom of the aniline must be substituted; no product was obtained when aniline was used as a nucleophile (2t) and we attribute this result to an unwanted fragmentation reaction after the P(V) intermediate is formed.[13] N-Methyl substituted systems work well (2u and 2v) and an N-Bn group can serve as a useful protecting group (2w). Indolines are also an important class of molecules that are competent nucleophiles (2x and 2y). Endocyclic aromatic heteronucleophiles also proved to be well suited to the strategy. Pyrrole formed coupled product 2z in good yield; however, we were surprised to find that indole did not undergo coupling (2aa). Our current hypothesis is that the 7-position C–H bond causes an unfavorable steric interaction in the coupling transition state. We were gratified to find that imidazoles and pyrazoles were effective in this approach (2ab-2af) although a 1,2,4-triazole did not result in any coupled product (not shown).

Table 2.

Scope of aromatic heteronucleophiles and heterocyclic phosphonium salts as coupling partners.

|

Yields of isolated products as single regioisomers are given.

Run in DME at 80 °C.

KH and 18-crown-6 used.

Yield calculated by 1H NMR due to product volatility

KH used.

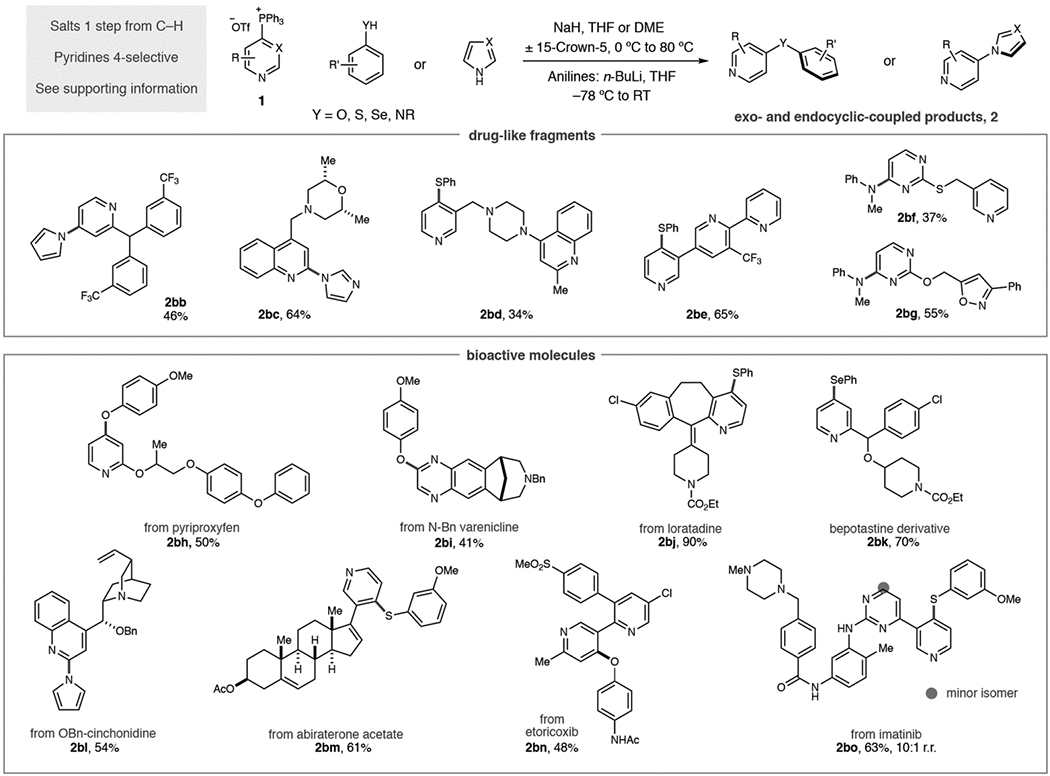

Our attention turned to the scope of heterocyclic phosphonium salts and, as seen in Table 2, various aromatic heteronucleophiles can be coupled to pyridine and diazine building blocks. It is important to note that all phosphonium salts were prepared from C–H precursors in a single step with complete control of regioselectivity in the vast majority of cases (see Supporting Information for details). Starting with mono-substituted pyridines: phenol, thiophenol and aniline nucleophiles can tolerate 3- substituents on the pyridine ring (2ag–2ai). An exception is shown in diarylamine 2aj where no product was observed. Methoxy substituents at the 2-position of pyridines result in moderate yields and 2,2-bipyridines are competent substrates (2ak–2am). Blocking the 4-position of pyridines results in salt formation at the 2-position; examples 2an–2aq show that C–O and C–N bond derivatives can be formed via this pathway. Disubstitution, such as 3,5-disubstituted pyridines are tolerated, as are 2,3- and 2,5-substitution patterns (2ar–2av). Quinolines are also effective substrates and can be coupled to phenols and thiophenols (2aw and 2ax). Diazine salts were examined under this reaction protocol; pyrimidines work well as partners (2ay–2ba) and functionalized quinoxaline 2bb was obtained in good yield. Complex pyridines and diazines are commonly found in medicinal chemistry programs and we employed the phosphonium-mediated process against a challenging set of drug-like fragments and biologically active molecules (Table 3).[14] These molecules are problematic for traditional methods, particularly metal-catalyzed processes, due to the difficulty in preparing halogenated precursors and the occurrence of polar functional groups that can disable catalytic processes. Salts derived from triphenylphosphine were synthesized in each case due its widespread availability, low cost, ease of salt purification and the consistently high regioselectivities observed.[15] First, we prepared six drug-like fragments that possess multiple functional groups and sites of reactivity. A pyrrole was coupled to a pyridine bearing a benzhydril center, and an imidazole-substituted quinoline was formed without difficulty (2bc and 2bd). Site-selective C–S bond-formation was possible in polyazines 2be and 2bf where the 3-substituted pyridine is the favored heterocycle based on preferential reactivity with Tf2O during phosphonium salt synthesis. We exploited our recently disclosed site-selective switching tactic in 2bg where selective C–P bond-formation occurs on the pyrimidine system and then coupled to an aniline.[10e] Para-methoxyphenol could also be coupled to a 1,2-oxazole-containing fragment (2bh). Second, we aimed to show that aromatic heteronucleophile coupling could be employed at advanced stages of drug development beyond fragment compounds.[16] To demonstrate this attribute, we chose a representative selection of complex drugs, and other bioactive molecules, with a range of structural and functional diversity. Phenols can be coupled to pyriproxyfen, a pesticide, and a protected version of the smoking cessation aid varenicline (2bi and 2bj). Loratadine and a bepotastine analogue are excellent coupling partners for thiophenols and selenophenols repectively (2bk and 2bl). Pyrrole can be coupled to benzyl-protected cinchonidine, and a thiophenol conjugate can be synthesized from the prostate cancer drug abiraterone acetate (2bm and 2bn). Site-selective processes were again exploited to make functionalized derivatives of etoricoxib and gleevec (2bo and 2bp) with the latter isolated as a 10:1 mixture of regioisomers.

Table 3.

Scope of drug-like fragments and complex bioactive molecules.

|

Yields of isolated products as single regioisomers are given unless stated.

Ran in DME at 80 °C

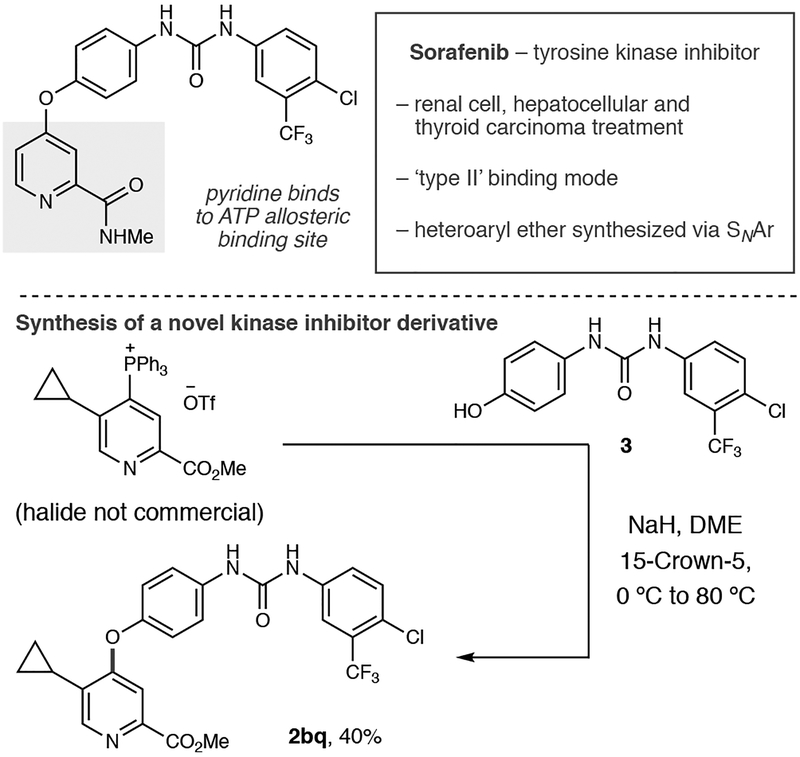

As a final demonstration of the utility of the coupling process, we examined a convergent coupling reaction to make a novel kinase inhibitor derivative that would be challenging to access via conventional metal-catalyzed cross coupling or SNAr reactions (Scheme 2). Sorafenib is a marketed tyrosine kinase inhibitor that contains a pyridine–O–aryl linkage (Scheme 2); in ‘type II binding’ the pyridine moiety occupies an allosteric pocket and competes with ATP.[1,2,17,18] We envisioned a convergent disconnection where a pyridylphosphonium salt could react with phenol 3 that includes the diaryl urea moiety. Scheme 2 shows a representative pyridine phosphonium salt where the corresponding halide would be challenging to prepare; coupling to phenol 3 proceeds in reasonable yield to form 2bq and demonstrates that novel kinase inhibitors can be rapidly synthesized via this approach.

Scheme 2.

Phosphonium coupling reactions to make novel kinase inhibitors.

In summary, we have shown that pyridine and diazine phosphonium salts can serve as coupling partners with seven classes of aromatic heteronucleophiles. Advantages of this strategy over conventional approaches include a distinct scope of azine coupling partners, a simplified mechanism and a narrow range of reaction conditions. Applying this method to complex drug-like molecules is also feasible and enables medicinal chemistry to rapidly access valuable analogues. The method also enables convergent couplings between two complex coupling partners and was exemplified by synthesizing a novel kinase inhibitor. Simple protocols, readily available reagents and applicability to pharmacogically-relevant molecules make this approach useful for medicinal chemists.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Metal-catalyzed approaches to azines to aromatic heteronucleophiles and a unified approach using phosphonium salts.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support by start-up funds from Colorado State University and from The National Institutes of Health under award number R01 GM124094.

References

- [1].Wu P, Nielsen TE, Clausen MH, Trends Pharmacol. Sci 2015, 36, 422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Johnson LN, Q. Rev. Biophys 2009, 42, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].For examples of SNAr reactions see: Walsh K, Sneddon HF, Moody CJ, RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 28072;Liu J, Robins MJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 5962.

- [4].For reviews see: Surry DS, Buchwald SL, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008, 47, 6338;Ruiz-Castillo P, Buchwald SL, Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 12564;Hartwig JF, Acc. Chem. Res 2008, 41, 1534;Kienle M, Dubbaka SR, Brade K, Knochel P, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2007, 2007, 4166;Rosen BM, Quasdorf KW, Wilson DA, Zhang N, Resmerita A-M, Garg NK, Percec V, Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 1346;Ley SV, Thomas AW, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2003, 42, 5400;Bhunia S, Pawar GG, Kumar SV, Jiang Y, Ma D, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 16136;Lee C-F, Liu Y-C, Badsara SS, Chem. Asian. J 2014, 9, 706.

- [5].For examples of recent light-driven processes see: Corcoran EB, Pirnot MT, Lin S, Dreher SD, DiRocco DA, Davies IW, Buchwald SL, David, MacMillan WC, Science 2016, 353, 279;Creutz SE, Lotito KJ, Fu GC, Peters JC, Science 2012, 338, 647;Lim C-H, Kudisch M, Liu B, Miyake GM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 7667;Ziegler DT, Choi J, Muñoz-Molina JM, Bissember AC, Peters JC, Fu GC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 13107;Uyeda C, Tan Y, Fu GC, Peters JC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 9548;Tan Y, Muñoz-Molina JM, Fu GC, Peters JC, Chem. Sci 2014, 5, 2831.

- [6].Finer JP, Ligand Coupling Reactions with Heteroaromatic Compounds, Tetrahedron Organic Chemistry Series, Pergamon Press, Oxford, Vol. 18 Chap. 4. [Google Scholar]

- [7].A similar strategy involving stoichiometric palladium complexes has been exploited for bioconjugation and fluorination reactions, see: Vinogradova EV, Zhang C, Spokoyny AM, Pentelute BL, Buchwald SL, Nature 2015, 526, 687;Lee E, Kamlet AS, Powers DC, Neumann CN, Boursalian GB, Furuya T, Choi DC, Hooker JM, Ritter T, Science 2011, 334, 639.

- [8].Blakemore DC, Castro L, Churcher I, Rees DC, Thomas AW, Wilson DM, Wood A, Nat. Chem 2018, 10, 383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Hilton MC, Dolewski RD, McNally A, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 13806; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Anders E, Markus F, Tetrahedron Lett 1987, 28, 2675; [Google Scholar]; c) Anders E, Markus F, Chem. Ber 1989, 122, 113; [Google Scholar]; d) Anders E, Markus F, Chem. Ber 1989, 122, 119; [Google Scholar]; e) Haas M, Goerls H, Anders E, E. Synthesis 1998, 195. [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Zhang X, McNally A, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 9833; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Koniarczyk JL, Hesk D, Overgard A, Davies IW, McNally A, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 1990; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Anderson RG; Jett BM; McNally A Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 3129; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Patel C, Mohnike ML, Hilton MC; McNally A, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 2607; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Dolewski RD, Fricke PJ, McNally A, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 8020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Larsen MA, Hartwig JF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 4287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Grayson M, Keough PT, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1960, 82, 3919; [Google Scholar]; b) Razuvaev GA, Osanova NA, Brilkina TG, Zinovjeva TI, J. Organomet. Chem 1975, 99, 93; [Google Scholar]; c) Razuvaev GA, Osanova NA, J. Organomet. Chem 1972, 38, 77; [Google Scholar]; d) Eyles CT, Trippett S, J. Chem. Soc. C 1966, 67; [Google Scholar]; e) Byrne PA, Ortin Y, Gilheany DG, Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].See the Supporting Information for a mechanistic scheme.

- [14].a) Vitaku E, Smith DT, Njardarson JT, J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 10257; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Baumann M, Baxendale IR, Beilstein J. Org. Chem 2013, 9, 2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Trialkylphosphines often result in regioisomeric mixtures during salt-formation and are more challenging to purify. The resulting salts are also less effective as coupling partners and result in a number of decomposition products.

- [16].Cernak T, Dykstra KD, Tyagarajan S, Vachal P, Krska SW, Chem. Soc. Rev 2016, 45, 546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wan PTC, Garnett MJ, Roe SM, Lee S, Niculescu-Duvas D, Good VM, Jones CM, Marshall CJ, Springer CJ, Barford D, Marais R, Cell, 2004, 116, 855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gotnik KJ, Verheul HMV, Angiogenesis 2010, 13, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.