Abstract

Objectives

Pneumonia remains a primary cause of death for under-five children. It is possible to reduce the mortality impact from childhood pneumonia if caregivers recognise the danger signs of pneumonia and obtain appropriate healthcare. Among caregivers, research on fathers’ healthcare-seeking behaviours and perceptions are limited, whereas research on mothers is available. This study aims to reveal fathers’ roles and perspectives with respect to the selection of care and treatment for children with pneumonia in a remote island of the Philippines.

Design

A qualitative research was carried out using semistructured interviews.

Setting and participants

The interviews were conducted with 12 fathers whose children had pneumonia-like episodes in the 6 months prior to the interview. Data analysis was performed using the concept analysis method to identify codes which were merged into subcategories and categories. Finally, the themes were identified.

Results

Three themes were identified as part of fathers’ roles, and two were identified as fathers’ perspectives on various treatment options. Fathers took care of their sick children by not entrusting care only to mothers because they considered this as part of their role. Notably, fathers considered that arranging money for the child’s treatment was a matter of prime importance. They selected a particular treatment based on their experiences and beliefs, including herbal medicine, home treatment, and visiting traditional healers and health facilities. Their decision was influenced by not only their perception of the severity of illness but also cultural beliefs on the cause of illness. Visiting health facilities, particularly during hospital admissions, causes significant financial burden for the family which was the main concern of fathers.

Conclusion

It is crucial to consider the cultural background and also imperative to address issues related to medical cost and the credibility of health facilities to improve fathers’ healthcare-seeking behaviour.

Keywords: health services research, pneumonia, qualitative study, child health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

While most previous studies focused on mothers’ healthcare-seeking behaviour for their children with pneumonia, this study emphasised the roles and perspectives of fathers which were of key importance when making a final decision in healthcare seeking.

We employed the framework of the theory of planned behaviour to discuss what factors influenced fathers’ intention in selecting care and treatment for their children with pneumonia.

While this study only considered a rural municipality in the Philippines and interviews were conducted with only 12 fathers, it does suggest that the medical cost and credibility of health facilities are likely to affect healthcare-seeking behaviour in similar settings.

Background

Although the under-five mortality rate has significantly reduced in the past decades, it is still estimated that 5.9 million children died in 2015 worldwide.1 Most of these deaths occur in low-income and middle-income countries owing to preventable or treatable infectious diseases such as pneumonia, diarrhoea and malaria.1

The Philippines is a lower middle-income country located in Southeast Asia.2 Although the under-five mortality rate dropped from 59 per 1000 in 1990 to 29 per 1000 in 2010,3 pneumonia remains the leading cause of deaths for children aged 1–4 years.4 The Philippines promotes the integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) approach which aims to reduce death, illness and disability from common childhood diseases including pneumonia. IMCI has both preventive and curative elements.5 Effective antibiotics for bacterial pneumonia are usually available in most health facilities in the Philippines. Therefore, early recognition of danger signs of pneumonia by caregivers and appropriate healthcare seeking can prevent deaths from childhood pneumonia.6–8 However, only half of the children with pneumonia in the Philippines have received treatment from appropriate providers.4

Most previous studies have analysed healthcare-seeking behaviours and perceptions of mothers regarding childhood pneumonia.9–14 Mothers had poor knowledge of the aetiology and danger signs of pneumonia.10 13They often self-medicate children with antibiotics and traditional medicines15–17 and take them to a traditional healer,18 19 which may delay appropriate treatment. Factors associated with healthcare-seeking behaviours include caregivers’ age, healthcare cost, distance to health facilities, knowledge of danger signs and children’s age.14 20 21Moreover, fathers’ educational status had a significant effect on mothers’ healthcare-seeking behaviour.14 Previous research showed that although mothers generally play an important role as the primary caregiver for a sick child, fathers’ opinions affect the decision of healthcare seeking.16 However, fathers’ ideas and the reasons behind the decision to seek healthcare remain largely unknown. This study was conducted to reveal fathers’ roles and perspectives on the selection of care and treatment for childhood pneumonia in a remote island of the Philippines.

The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is one of the influential models for identifying a decision making process to translate into action.22–25 In the TPB, there are three belief-based constructs: attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control.25 When a person intends to perform a given behaviour, the intention is influenced by his or her own attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control.22–25 Behaviour of fathers’ health seeking for their sick children may be driven by their intention to decide which in turn will be influenced by several factors. Based on the TPB framework, we discussed what factors influenced their intention when fathers selected care and treatment for their children.

Methods

Study design

This study employed a qualitative investigation method using semistructured individual interviews. We used a qualitative content analysis approach which is suitable for analysing the common issues mentioned in describing data,26 interpreting meaning from the content of text data,27 and systematically categorising and summarising large volumes of data.28 Qualitative content analysis is mainly inductive and is not based on previous theories or hypotheses.27 28 We believe that this analytical approach is appropriate to extract categories from meaningful statements.

Study area

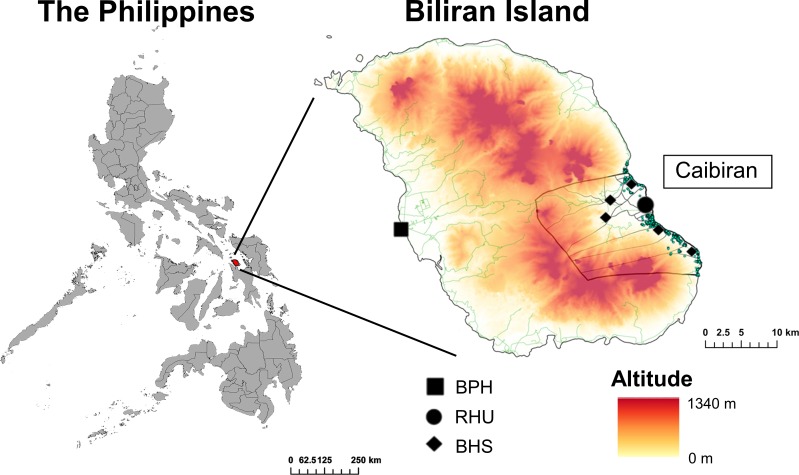

The study was conducted in the Municipality of Caibiran of Biliran Province in the Eastern Visayas Region of the Philippines (figure 1). Biliran Province has 1 72 000 inhabitants and consists of one main island (Biliran Island) and other small islands. The province has eight municipalities, and Caibiran is one of them with a population of around 22,500.29 Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine in Japan and the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM) in the Philippines conducted a joint research project titled ‘Comprehensive Etiological and Epidemiological Study on Acute Respiratory Infections in Children’ from 2011 to 2017. The main objective of this project was to provide evidence to reduce the impact of paediatric acute respiratory infections including pneumonia. The project’s main component was a cohort study conducted in Biliran Island, including the Municipality of Caibiran, with children under 5 years of age. Therefore, we selected Caibiran as our study site.

Figure 1.

Biliran Province in the Eastern Visayas Region of the Philippines. BHS, barangay health stations; BPH, Biliran Provincial Hospital; RHU, rural health unit.

The Philippines has public sector primary health facilities and hospitals. barangay health stations (BHS) and rural health units (RHU) provide primary health services. BHS provides prenatal and postnatal care, immunisation, health education, and limited clinical consultation with one assigned midwife and several barangay health workers (health volunteers). RHU provides outpatient care, delivery, and the same services as BHS with one qualified doctor and several nurses and midwives. Each province usually has one provincial hospital and some district hospitals.30 Caibiran has one RHU and six BHS. Biliran Provincial Hospital, a secondary level referral hospital, the only hospital in Biliran Province, is located in Naval, the capital of the province, around 30 km away from Caibiran.

Participants

Participants of this study were fathers whose children were registered in the childhood pneumonia study, in which children under 5 years of age were observed to define the incidence, aetiology and risk factors for pneumonia. Caregivers of children in the intervention study were requested to record symptoms of acute respiratory infections such as a cough, difficulty breathing and chest indrawing. We used the purposive sampling method, checking all registered records and identified children who had pneumonia-like episodes (a cough or difficulty breathing, plus chest indrawing) in the 6 months prior to the interviews with fathers. Fourteen fathers were extracted but two fathers were excluded; one went away to work in the capital city of Manila and another was divorced and living apart with the child before the interview. Finally, 12 fathers were selected as participants.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the development of the research question; the design of, recruitment for and conduct of the study; or in the dissemination of the study’s findings.

Data collection

Semistructured interviews were conducted from 18 to 22 November 2016 using open-ended questions. The questions sought information on fathers’ perceptions of pneumonia, their behaviour and actions for care and treatment, and roles and responsibilities when children had pneumonia-like episodes. We did not ask questions based on each TPB item—intention, attitude, subjective norms and perceived behaviour control—as we wanted to obtain the entire picture regarding fathers’ views. Prior to asking the main questions, we also asked some questions to obtain demographic information and necessary data to assess the socioeconomic status (SES) of the household. We used a simple poverty scorecard to assess the household SES using 10 simple questions.31 32 The maximum total score was 100 and the minimum was 0, with a lower score indicating a lower SES.

Face-to-face interviews were conducted in English and three interpreters took turn to translate the questions and answers from English to the local language and vice versa. The interpreters were female nurses and were fluent in the Waray-Waray language (the main local language of the Municipality of Caibiran) and English. Prior to conducting the interviews, a researcher trained the three interpreters in the research objectives, contents and interview procedure. All interviews were conducted at the participants’ house by a team of three members including the main interviewer (the first author who had prior experience in qualitative research and global health), the main interpreter (translating English into Waray-Waray and vice versa) and an assistant interpreter (supporting the main interpreter and recording field notes). The interviewer and participants did not have any relationships prior to the commencement of the study. On a few occasions, participants’ small children interrupted the interviews which needed to be delayed until they disappeared. At the end of interviews, the assistant interpreter summarised the fathers’ answers to confirm the interview findings with the fathers and the interviewer. All interviews were audio recorded with permission from the participants, and lasted 22–54 min (average: 32.9 min). No further interviews were considered necessary as the interviewer and the assistants agreed that data saturation was reached.

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed in Waray-Waray, and the transcription was translated into English by an interpreter. The English translation was back-translated into Waray-Waray to verify the accuracy. The English-transcribed interviews were checked and re-read several times to eliminate ambiguities. The first author then selected the meaningful units from the transcript according to the study objectives which were then refined and assigned codes. Selected codes were verified by the other three researchers to ensure the code reflected the meaning of each unit. After identifying all codes, the researchers grouped them into subcategories based on similarities and differences. These subcategories were eventually combined into main categories.27 28 Finally, the themes were identified as factors affecting fathers’ healthcare-seeking behaviours. During the analysis, the researchers engaged in extensive discussions until consensus was reached on codes, subcategories, main categories and themes. The researchers discussed their findings and any coding discrepancies to maximise rigour and reliability. We followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research (COREQ) checklist which is shown in online supplementary appendix table1.

bmjopen-2018-023857supp001.pdf (317.2KB, pdf)

Results

Participant demographics are provided in table 1. The mean age of the participants was 32.7 (SD±9.5), and half of them were in their 20 s. Five had not competed elementary school, and four had studied beyond the high school level. All participants had jobs. Except for one participant, all others had two to seven children, with a mean of 3.2 (SD±1.7). Eight had experienced admitting at least one of their children in a hospital in the past. The SES scorecard ranged from 14 to 57, with a mean of 28.6 (SD±12.8). Out of the 12 households, scores of 8 households were less than 31 which is the national poverty threshold, meaning the minimum level of income in the Philippines.27 28 Among children who had a pneumonia-like episode, three were female, nine were male and four were under 1 year of age.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

| Demographic details (range) | Mean (SD) | N | % |

| Age 23–52 years old) | 32.7 (SD±9.5) | ||

| 20–29 | 6 | 50 | |

| 30–39 | 3 | 25 | |

| 40–49 | 2 | 17 | |

| ≥50 | 1 | 8 | |

| Education | |||

| Not completed elementary school | 5 | 42 | |

| Not completed high school | 4 | 33 | |

| Beyond high school education | 3 | 25 | |

| Occupation | |||

| Farmer | 4 | 33 | |

| Fisherman | 2 | 17 | |

| Driver | 2 | 17 | |

| Others | 4 | 33 | |

| No of children (1–7 children) | 3.2 (SD±1.7) | ||

| 1 | 1 | 8 | |

| 2 | 4 | 33 | |

| 3 | 4 | 33 | |

| ≥4 | 3 | 25 | |

| Experience of previous hospitalisation of any children | |||

| Yes | 8 | 67 | |

| No | 4 | 33 | |

| Experience of losing any children in the past | |||

| Yes | 2 | 17 | |

| No | 10 | 83 | |

| Simple Poverty Score card (14-57) | 28.6 (SD±12.8) | ||

| <31 | 8 | 67 | |

| ≥31 | 4 | 33 | |

| Gender of the child with pneumonia-like episode | |||

| Female | 3 | 25 | |

| Male | 9 | 75 | |

| Age of the child with pneumonia-like episode (years) | |||

| <1 | 4 | 33 | |

| 1 to <2 | 2 | 17 | |

| 2 to <3 | 3 | 25 | |

| 3 to <4 | 2 | 17 | |

| 4 to <5 | 1 | 8 | |

Fathers’ role

Three themes were identified in relation to fathers’ role in caring for a sick child: belief in their own judgement, arranging money and responsibility as the leader of the family (table 2). Brief transcripts of the fathers’ interviews are shown as examples which are indicated in italics with the fathers’ identity number (F1–F12).

Table 2.

Themes and categories of fathers’ role identified from in-depth interviews with fathers whose children had pneumonia-like episodes in Biliran Island, the Philippines

| Themes | Categories |

| Belief in their own judgement | Fathers observe and care for their sick child at home for a few days. |

| Some fathers do not know about pneumonia. | |

| Arranging money | Fathers work and save money for their child’s treatment. |

| Money issues come first to fathers’ minds when their child is hospitalised. | |

| Responsibility as the leader of the family | Fathers intend to take responsibility for their child. |

| Fathers assist mothers who play a key role in caring for a sick child. |

Belief in their own judgement

Five fathers mentioned that they checked and treated their child at home when he/she had a cough and fever for a few days instead of immediately taking the child to a health facility. Fathers checked for fever by touching the child’s forehead and observed other symptoms such as non-stop crying, restlessness and loss of appetite. One father cuddled his child to make him/her feel better, and another cleaned the child’s surroundings. Seven fathers knew that applying cold water reduced fever:

‘We know how to give first aid. If my child has fever, we wipe him with a wet towel to lower his temperature (F10)’.

Fathers believed that a sick child needed nutritious foods, such as fruits, vegetables, eggs and fish, and easy-to-digest foods such as porridge. One father recognised the importance of the child drinking an adequate amount of water. Some fathers bought biscuits or soft drinks which they usually could not afford, and one father gave what his own mother used to give him when he was sick in his early childhood:

‘If I have money, I buy eggs for my sick child. If I don’t, I just buy royal (soft drink), because that was what my mother used to give me (F6)’.

Ten fathers had heard of pneumonia. One of them whose family member had been diagnosed with pneumonia remembered details such as symptoms and treatment. Two fathers had never heard of pneumonia. Their recognition of pneumonia symptoms varied, covering cough, asthma, weakness, irritability, fever, difficulty in breathing, crackling sound in the chest and convulsions:

‘She had a hard cough, she had difficulty breathing, a crackling sound could be heard when she would breathe. That’s what I observed in my child (F2)’.

Arranging money

Fathers believed that it was their responsibility to earn money for their family needs, including money necessary to treat and to prepare for their child’s illness. One father who had lost his first child saved money whenever he had extra income:

‘We usually save even 50 pesos if we make extra, because we do not know when the child may need to go to a hospital again (F4)’.

When hospitalisation was required, fathers first thought of money. Most fathers had struggled with money issues, such as figuring out from whom to borrow and how to repay the loan. Most of them borrowed money from their relatives and friends. Some fathers asked for financial help from politicians for their children’s hospital expenses. Some of them were still repaying debt:

‘I felt different. I was afraid. I was worried because I did not have any money. I looked for money and asked for it from my neighbours (F1)’.

Responsibility as the leader of the family

Fathers considered themselves the leader of the family who solves any problem that occurs in the family. They took various actions to improve their sick child’s health, such as seeking information from other people:

‘I look after my children, wipe them if they are sweating, and I ask other people about what to do (F6)’.

Fathers were also the main decision makers regarding which facility to use. Although fathers discussed such matters with mothers, they were proud to be the primary decision maker:

‘If I see that my child is unwell, I bring him to RHU. I talk to my wife, but I am the one who decides (F6)’.

Although fathers helped care for their sick children, mothers were the main caregivers. Three fathers had never accompanied a child to RHU, and two fathers had only dropped off the mother and child in front of the RHU. Fathers assisted mothers in caring for a sick child:

‘I gave my wife some ice. I waited for the ice to melt and then wiped the child (F9)’.

Father’s experiences of and perspectives on various treatment options

Two themes were identified in relation to fathers’ experiences of and perspectives on various treatment options: fathers’ way of taking care of their sick children and their preference of health facilities (table 3).

Table 3.

Themes and categories of fathers’ experiences and perspectives identified from in-depth interviews with fathers whose children had pneumonia-like episodes in Biliran Island, the Philippines

| Themes | Categories |

| Fathers’ way of taking care of their sick children | Herbal medicines are easy to prepare at home. |

| Some fathers keep a stock of medicines at home. | |

| Some fathers do not have enough knowledge about medication. | |

| Fathers’ preference of health facilities | Fathers takes their child to a traditional healer because of their therapeutic efficacy. |

| Fathers generally do not prefer BHS. | |

| Fathers take their child to RHU for a medical consultation. | |

| Fathers expect to receive medicines for their sick child from RHU. | |

| Fathers prefer to be seen by a staff member with medical expertise. | |

| Fathers rely on health staff advice to refer their child to a hospital. |

BHS, brangay health stations; RHU, rural health unit.

Fathers’ way of taking care of their sick children

Fathers procured herbal medicines for a cough from a garden or from neighbours. Most fathers believed that oregano and five-leaved chaste tree leaves were effective for a cough and asked mothers to make herbal medicines for the child. Fathers had their own methods of preparing herbal medicine: just boiling the leaves in water, crushing or steaming the leaves, and squeezing out the juice. Three fathers added lemon and sugar or milk to the medicine for taste. Three fathers recognised that herbal medicines could have limited effectiveness, two fathers had never used them and two fathers avoided using them:

‘We used oregano because it is easy to use. A cough was relieved by the herbal medicine but relapsed after getting better once (F12)’.

Fathers used two kinds of medicines for their children: antibiotics for a cough and antipyretics for fever. Three fathers did not have any stock of medicines at home. Some of them bought medicines without prescription at a pharmacy, while some asked neighbours and relatives to give them medicines:

‘I asked my mother-in-law for medicine since she had a stock of medicines from the congressman (F9)’.

Although fathers used Western medicines such as antibiotics, they did not know their names or dosage. Mothers handled these aspects. One father had no idea what antibiotics were:

‘We gave the child paracetamol liquid, but I do not know the dosage. I don’t have any idea what antibiotics are. What is that? I think it is cephalexin (F8)’.

Taking a sick child to a traditional healer was a common choice of fathers. Most fathers brought their children to RHU after a traditional healer failed to treat the child. One father used both RHU and a traditional healer on the same day, another father took his child to a traditional healer when the child did not recover after going to RHU, and the others took their children to a traditional healer after providing them with home treatment:

‘If my child has fever, we bring him to the traditional healer. In a few days, he gets better (F6)’.

Fathers believed that suffering from a sprain, fracture or some other pain made the child sick with fever, cough or vomiting:

‘Sometimes when the child had fever, people said the child had piang (sprain or dislocation of tissues or bones). Sometimes when the child experienced body pain, the child had fever (F5)’.

A traditional healer generally checks nerves, applies a liniment and gives the child a massage while chanting rituals. Fathers believed a traditional healer’s treatment to be effective as they had seen their child recover after receiving such treatment:

‘When my child was treated by a traditional healer, he seemed at ease. I was free from worry (F12)’.

Traditional healers charge a small amount of money and do not have a fixed fee. One father did not like to go to a traditional healer as he thought it risky:

‘I don’t like traditional healers. I cannot take a risk when it comes to my child. I prefer to bring him to RHU first. I don’t like to take him to a traditional healer (F2)’.

Fathers’ preference of health facilities

Fathers generally did not prefer to take their child to BHS. They preferred taking the child directly to RHU without using BHS, because the latter has insufficient equipment, and fathers perceive that it is closed all the time. Two fathers noted that BHS staff always referred a child either to an RHU or to a hospital.

Fathers preferred RHU because of its closer distance and availability of medicines. RHU provides medicines for free if they have a stock. However, when there was no stock of medicines at RHU, they had to buy medicines themselves:

‘When my child’s condition became worse with a cough with sputum, we brought him to RHU. But they did not have a stock of medications. I paid 105 pesos for amoxicillin (F6)’.

Some of them could not afford to buy medicines because they did not have enough money:

‘RHU staff gave me a prescription. But I could not buy the medicines as I did not have enough money (F2)’.

Fathers thought that RHU staff had good knowledge about diseases and knew how to cure the child. Some fathers had witnessed RHU staff listening to the child’s chest sounds, fanning a child to bring down the fever and using oxygen or a nebuliser when the child had difficulty breathing:

‘RHU staff used a fan for my child to relieve fever. Only in the case that he suffers from difficulty in breathing, they use something like oxygen and nebulizer. It heated and made steam (F10)’.

Fathers took their children to RHU to be checked, particularly by a doctor:

‘I think that only a doctor knows what kind of medicines my child needs, and we are not convinced unless a doctor checks my child (F1)’.

However, they recognised that a doctor was not always available and that only some nurses and midwives might be available at RHU. Nurses at RHU sometimes referred a child to a hospital when they could not handle the situation themselves:

‘Once, a nurse prescribed antibiotics for a cough when I brought my child to RHU. I argued with her because she was not a doctor (F11)’.

Eight fathers had past experiences of having admitted their children to a hospital for different reasons, with the treatment leading to recovery. Some fathers took their children to a hospital when their condition became serious. Fathers mostly complied with the doctor’s recommendation to go to a hospital. One father did not comply with such a recommendation when he did not have any money:

‘If it is an emergency, surely, I bring my child to a hospital. The important thing is for my child to be okay (F2)’.

Discussion

The study revealed that fathers monitored their sick child at home by assessing the child’s symptoms and providing some care, since they considered these as part of their role as fathers. This role comprises their subjective norms as the breadwinner of their family which is a constitutive part of the TPB. Though mothers are the main caregivers,11–14 fathers did not entrust the care of their sick children solely to mothers. As confirmed by previous studies, fathers play an important role in financing for child care.33 They recognised this as their responsibility and attempted to fulfil it. In this study, it was found that paying incidental costs, such as those for medicine, posed a significant problem for fathers when healthcare facilities including hospitals could not provide free medication for their children. Our study participants were generally poor, and our previous study conducted in Biliran Island indicated that low SES scores were associated with a higher incidence of pneumonia-like episodes.34 Moreover, there was a positive correlation between SES and the proportion of appropriate healthcare-seeking behaviours in a study in Ethiopia.35 Although the Philippines has a health insurance scheme called the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth)36 that covers around 79% of the population to improve universal health coverage, it does not cover full costs of treatment,37 such as the out-of-pocket cost for medication when health facilities do not have a stock of medicines. A high level of out-of-pocket payments influences the utilisation rates of public healthcare.38 As most participants had difficulties in paying the treatment cost for hospitalisation, this may be a primary barrier for appropriate healthcare seeking, particularly taking children to the hospital for admission. This treatment cost and financing issue could be one of the main factors of perceived behavioural control that affect fathers’ intention to select health facilities, that is, fathers’ healthcare seeking.

Herbal medicines were also commonly used by our study participants. The Philippines government promotes the use of some herbal medicines that are cheap and readily available.39 40 Fathers also used antipyretics for fever, and antibiotics and herbal medicines to treat coughs at home. Providing treatment at home might be one of the components of behavioural attitude since fathers may resort to home treatment when they perceive the condition of their sick children as mild. A previous study in the Philippines revealed that 43% of caregivers bought medications without a prescription and that they engaged in home treatment to save time and money.41 The use of drugs without a prescription, particularly antibiotics, is of concern. Home treatment is risky because of its low effectiveness and potential side effects, including the emergence of antimicrobial resistance.42 However, caregivers are usually not aware of side-effects and drug efficacy.43 Additionally, a gap may exist between illness recognition and seeking outside care because of the wait to complete a drug course which can result in a major delay in getting appropriate treatment.17 44 Previous studies have shown that home treatment is associated with a delay in seeking appropriate treatment.9 13 It is not practical to bring all children with acute respiratory infections to health facilities since these symptoms are very common among children and the majority are self-limited. However, caregivers including fathers should recognise the danger signs of pneumonia which require urgent medical attention.

Fathers play an important role in deciding the care or treatment that is provided at home or at health facilities. A previous study indicated that most mothers decided to seek assistance from outside the home after discussing the situation with their husbands,45 and some studies showed that fathers play the role of the primary decision maker regarding their children’s healthcare seeking.33 46–48 Three key steps were shown to prevent pneumonia deaths of children aged under five: recognising that a child is sick, seeking appropriate care and treating appropriately with antibiotics.6 In our study, fathers did not have a clear understanding of pneumonia symptoms and danger signs of sick children, and little understanding of the danger signs and severity could affect fathers’ attitude to immediately access appropriate healthcare services. Mothers know the disease named pneumonia but have poor knowledge of the aetiology and danger signs of probable pneumonia.10 12 It is usually difficult to recognise the seriousness of certain acute respiratory infections such as pneumonia.7 The positive predictive value of caregiver diagnosis and knowledge of pneumonia was lower than that of those of diarrhoea and malaria.21 49 The lack of recognition of signs of severe illness by caregivers is the most commonly cited reason for not seeking appropriate healthcare.50 Caregivers with a lower level of education are more likely to resort to home treatment and/or traditional healers as their initial action,10 and they should therefore be provided with the necessary knowledge about pneumonia.6 51 Generally, health education programmes in the community target mothers and fathers who have fewer opportunities to expand their knowledge. Considering their important role in the decision-making process, it is necessary to offer health education programmes to increase fathers’ knowledge and make the healthcare system more trustworthy to fathers.52 53

Fathers were found to take their own decisions in selecting facilities for treatment. They took their children to traditional healers when they thought that the child had ‘piang’ before visiting RHU. Piang refers to a sprain or dislocation of tissues or bones in the chest or back which result in symptoms such as fever and cough.54 When they believed that the child had an accident or sprain, they tended to prefer traditional healers. Such a cultural belief may also be an important component of fathers’ attitude. Based on this belief, fathers preferred to visit traditional healers despite the unfavourable evaluation of the outcome of the child’s symptoms. In the Philippines, people often consider a cough and fever to be caused by ‘piang’. Illness in the ‘piang’ complex can be traced back to the child falling down or being handled incorrectly by their mothers or elder siblings, and it is generally believed that only traditional healers can treat this condition.54 Such local beliefs might be a hidden barrier for inappropriate healthcare-seeking behaviour and could lead to delay in consulting medical professionals at appropriate health facilities.54 Since cultural and social beliefs about the causation and treatment of illness cannot be ignored, it is crucial to understand them to promote appropriate healthcare-seeking behaviours. Furthermore, fathers prefer to use traditional healers because of the mode of payment. The mechanism of paying a traditional healer is more flexible and affordable.13 16 Some fathers in our study were disappointed with the absence of doctors in RHU. Health services should also be more friendly towards fathers; that is, they should be made parent-friendly instead of only mother-friendly.55 In over 90% of cases, one reason for eventually visiting health facilities was the worsening of the child’s condition.13 If health facilities become more reliable by ensuring the continuous presence of healthcare staff, particularly doctors, and the constant availability of free medication, caregivers may prefer to directly take their children to health facilities such as RHU.

This study, however, has some limitations. We were unable to distinguish fathers whose children had been taken to RHU from those whose children had not been taken because of the uncertainty of health records. Second, this study was conducted in just one rural municipality of the Philippines, which was located in a remote island, and the interviews were conducted with only 12 fathers. Third, though we adhered to the COREQ guidelines,56 we could not re-evaluate the returned transcripts or check on participants because it was difficult to contact the participants again. However, we tried to summarise the findings with each participant at the end of the interviews and confirmed reliability. Fourth, the study was conducted in two languages, English and the local language. Although we made every effort to ensure an accurate interpretation, the possibility of inaccurate interpretation and/or translation cannot be entirely eliminated. However, we believe that this study provides some important insights into fathers’ perceptions and healthcare-seeking behaviours related to childhood pneumonia. Further studies should include other settings, use both qualitative and quantitative methods to analyse healthcare-seeking patterns, and conduct a comparison of the roles of mothers and fathers.

Conclusion

Fathers in our study tended to take responsibility for caring for their sick children and made treatment decisions when their children had pneumonia-like episodes. They usually waited and observed their sick children at home or relied on traditional healers before using formal health facilities. Arranging money for the treatment of their sick children was their major role. Regarding their role in deciding the treatment options, healthcare providers need to understand fathers’ roles and perspectives when formulating health education programmes. It is crucial to consider cultural background such as local beliefs. It is also imperative to address issues related to medical cost and the credibility of health facilities to improve fathers’ healthcare-seeking behaviours.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the participants who generously shared their time and experiences with us, as well as the supporting staff who provided assistance as interpreters.

Footnotes

Contributors: MS, ARN and HO were involved in the conception and design of the study. MS and RT carried out the acquisition of data. MS, NO, KS and HO conducted data analysis and interpretation. JL, PPA, SL and RT provided background information on the study site. VLT critically revised the manuscript for important cultural and intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was conducted with financial support from The Konosuke Matsushita Memorial Foundation, JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number17K09189, Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) under Grant Number JP16jm0110001, and Tohoku University Center for Gender Equality Promotion.

Disclaimer: The funding authorities had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicines (No. 2014-1-790), the Institutional Review Board of Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, Philippines (No. 2016-25).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Anonymised interview transcripts can be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. You D, Hug L, Ejdemyr S, et al. . Global, regional, and national levels and trends in under-5 mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Lancet 2015;386:2275–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00120-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Bank. Data World Bank country and lending groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (cited 20 Dec 2017).

- 3. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Maternal and newborn health country profiles the Philippines. https://www.unicef.org/philippines/MNH_Philippines_Country_Profile.pdf (cited 20 Dec 2017).

- 4. Department of Health,. Republic of the Philippines. Leading causes of child mortality http://www.doh.gov.ph/node/1488 (cited 20 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization. Towards a grand convergence for child survival and health: a strategic review of options for the future building on lessons learnt from IMNCI. 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/251855/1/WHO-MCA-16.04-eng.pdf?ua=1 (cited 20 Dec 2017).

- 6. The United Nations Children’s Fund(UNICEF) / World Health Organization. Pneumonia: the forgotten killer of children. 2006. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43640/1/9280640489_eng.pdf (cited 20 Dec 2017).

- 7. Scott JA, Wonodi C, Moïsi JC, et al. . The definition of pneumonia, the assessment of severity, and clinical standardization in the Pneumonia etiology research for child health study. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54 Suppl 2:S109–S116. 10.1093/cid/cir1065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. Integrated management of childhood illness Chart Booklet. 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/104772/16/9789241506823_Chartbook_eng.pdf?ua=1 (cited 20 Dec 2017).

- 9. Diaz T, George AS, Rao SR, et al. . Healthcare seeking for diarrhoea, malaria and pneumonia among children in four poor rural districts in Sierra Leone in the context of free health care: results of a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2013;13:157 10.1186/1471-2458-13-157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ndu IK, Ekwochi U, Osuorah CDI, et al. . Danger signs of childhood Pneumonia: caregiver awareness and care seeking behavior in a developing Country. Int J Pediatr 2015;2015:1–7. 10.1155/2015/167261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kanté AM, Gutierrez HR, Larsen AM, et al. . Childhood illness prevalence and health seeking behavior patterns in rural Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2015;15:951 10.1186/s12889-015-2264-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seidenberg PD, Hamer DH, Iyer H, et al. . Impact of integrated community case management on health-seeking behavior in rural Zambia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012;87:105–10. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ukwaja KN, Talabi AA, Aina OB. Pre-hospital care seeking behaviour for childhood acute respiratory infections in south-western Nigeria. Int Health 2012;4:289–94. 10.1016/j.inhe.2012.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gelaw YA, Biks GA, Alene KA. Effect of residence on mothers’ health care seeking behavior for common childhood illness in Northwest Ethiopia: a community based comparative cross--sectional study. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:705 10.1186/1756-0500-7-705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abbey M, Chinbuah MA, Gyapong M, et al. . Community perceptions and practices of treatment seeking for childhood pneumonia: a mixed methods study in a rural district, Ghana. BMC Public Health 2016;16:848 10.1186/s12889-016-3513-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bakshi SS, McMahon S, George A, et al. . The role of traditional treatment on health care seeking by caregivers for sick children in Sierra Leone: results of a baseline survey. Acta Trop 2013;127:46–52. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Källander K, Hildenwall H, Waiswa P, et al. . Delayed care seeking for fatal pneumonia in children aged under five years in Uganda: a case-series study. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:332–8. 10.2471/BLT.07.049353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. D’Souza RM. Role of health-seeking behaviour in child mortality in the slums of Karachi, Pakistan. J Biosoc Sci 2003;35:131–44. 10.1017/S0021932003001317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tupasi TE, Radhakrishna S, Co VM, et al. . Bacillary disease and health seeking behavior among Filipinos with symptoms of tuberculosis: implications for control. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2000;4:1126–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Noordam AC, Carvajal-Velez L, Sharkey AB, et al. . Care seeking behaviour for children with suspected pneumonia in countries in sub-Saharan Africa with high pneumonia mortality. PLoS One 2015;10:e0117919 10.1371/journal.pone.0117919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Geldsetzer P, Williams TC, Kirolos A, et al. . The recognition of and care seeking behaviour for childhood illness in developing countries: a systematic review. PLoS One 2014;9:e93427 10.1371/journal.pone.0093427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Questions raised by a reasoned action approach: comment on Ogden (2003). Health Psychol 2004;23:431–4. 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour is alive and well, and not ready to retire: a commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau, and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychol Rev 2015;9:131–7. 10.1080/17437199.2014.883474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychol Health 2011;26:1113–27. 10.1080/08870446.2011.613995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991;50:179–211. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15:398–405. 10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holloway I, Wheeler S. Qualitative research in nursing and health care. 3rd edn West Sussex UK: A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., publication, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Republic of the Philippines, Philippines Statistics Authority. Population of Region VIII - Eastern Visayas (Based on the 2015 Census of Population). 2016. https://psa.gov.ph/content/population-region-viii-eastern-visayas-based-2015-census-population (cited 20 Dec 2017).

- 30. Asian Institute of Management. Overview of health sector reform in the Philippines and possible opportunities for public-private partnerships. 2010. (cited 20 Dec 2017).

- 31. Schreiner M. A simple poverty scorecard for the Philippines 2007. Philippine Journal of Development. 2007;XXXIV:2 https://dirp3.pids.gov.ph/ris/pjd/pidspjd07-2poverty.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schreiner M. Simple poverty scorecard Philippines. 2014. http://www.microfinance.com/English/Papers/Scoring_Poverty_Philippines_2009_EN.pdf (cited 20 Dec 2017).

- 33. Iganus R, Hill Z, Manzi F, et al. . Roles and responsibilities in newborn care in four African sites. Trop Med Int Health 2015;20:1258–64. 10.1111/tmi.12550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kosai H, Tamaki R, Saito M, et al. . Incidence and risk factors of childhood pneumonia-like episodes in Biliran Island, Philippines-A community-based study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0125009 10.1371/journal.pone.0125009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Deressa W, Ali A, Berhane Y. Household and socioeconomic factors associated with childhood febrile illnesses and treatment seeking behaviour in an area of epidemic malaria in rural Ethiopia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2007;101:939–47. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kozhimannil KB, Valera MR, Adams AS, et al. . The population-level impacts of a national health insurance program and franchise midwife clinics on achievement of prenatal and delivery care standards in the Philippines. Health Policy 2009;92:55–64. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Obermann K, Jowett MR, Alcantara MO, et al. . Social health insurance in a developing country: the case of the Philippines. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:3177–85. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Alvesson HM, Lindelow M, Khanthaphat B, et al. . Coping with uncertainty during healthcare-seeking in Lao PDR. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2013;13:28 10.1186/1472-698X-13-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Philippine Herbal Medicine. Ten (10) herbal medicines in the Philippines approved by the Department of Health (DOH). http://www.philippineherbalmedicine.org/doh_herbs.htm (cited 20 Dec 2017).

- 40. Philippines Herbal Medicine. Oregano (Origanum vulgare). http://www.philippineherbalmedicine.org/oregano.htm (cited 20 Dec 2017).

- 41. Kim SA, Capeding MR, Kilgore PE. Factors influencing healthcare utilization among children with pneumonia in Muntinlupa City, the Philippines. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2014;45:727–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Morgan DJ, Okeke IN, Laxminarayan R, et al. . Non-prescription antimicrobial use worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:692–701. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70054-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Le TH, Ottosson E, Nguyen TK, et al. . Drug use and self-medication among children with respiratory illness or diarrhea in a rural district in Vietnam: a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc 2011;4:329–36. 10.2147/JMDH.S22769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Källander K, Tomson G, Nsungwa-Sabiiti J, et al. . Community referral in home management of malaria in western Uganda: a case series study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2006;6:2 10.1186/1472-698X-6-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McNee A, Khan N, Dawson S, et al. . Responding to cough: boholano illness classification and resort to care in response to childhood ARI. Soc Sci Med 1995;40:1279–89. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00242-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mirzaei K, Milanifar A, Asghari F. Patients’ perspectives of the substitute decision maker: who makes better decisions? J Med Ethics 2011;37:523–5. 10.1136/jme.2010.040691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Franckel A, Lalou R. Health-seeking behaviour for childhood malaria: household dynamics in rural Senegal. J Biosoc Sci 2009;41:1–19. 10.1017/S0021932008002885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Greene ME, Mehta M, Pulerwitz J, et al. . ‘Involving men in reproductive health: contributions to Development’ 17- 24. https://www.faithtoactionetwork.org/resources/pdf/Involving%20Men%20in%20Reproductive%20Health-Contributions%20to%20Development.pdf (cited 20 Dec 2017).

- 49. Bedford KJ, Sharkey AB. Local barriers and solutions to improve care-seeking for childhood pneumonia, diarrhoea and malaria in Kenya, Nigeria and Niger: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2014;9:e100038 10.1371/journal.pone.0100038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Deutscher M, Beneden CV, Burton D, et al. . Putting surveillance data into context: the role of health care utilization surveys in understanding population burden of pneumonia in developing countries. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2012;2:73–81. 10.1016/j.jegh.2012.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. World Health Organization. Pneumonia fact sheet. 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs331/en/ (cited 20 Dec 2017).

- 52. Su D, Huang TT, Anthony R, et al. . Parental perception of child bodyweight and health among Mexican-American children with acanthosis nigricans. J Immigr Minor Health 2014;16:874–81. 10.1007/s10903-013-9869-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Phimmasane M, Douangmala S, Koffi P, et al. . Factors affecting compliance with measles vaccination in Lao PDR. Vaccine 2010;28:6723–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tallo V. Piang, panuhot or the moon: the folk etiology if cough among boholano mothers. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.489.2385&rep=rep1&type=pdf (cited 20 Dec 2017).

- 55. Davis J, Vyankandondera J, Luchters S, et al. . Male involvement in reproductive, maternal and child health: a qualitative study of policymaker and practitioner perspectives in the Pacific. Reprod Health 2016;13:81 10.1186/s12978-016-0184-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023857supp001.pdf (317.2KB, pdf)