Abstract

The manifestations of pulmonary cryptococcosis with multiple nodules or masses on computed tomography (CT) are diverse and difficult to differentiate from those of lung cancer and pulmonary tuberculosis. The present study compared the multislice spiral CT signs with pathological results and used the pathological results to explain the CT signs with the aim of improving the accuracy of the diagnosis of this disease. A retrospective analysis of 20 patients with primary pulmonary cryptococcosis with multiple nodules or masses was performed. Based on the CT signs, eight patients had been misdiagnosed with lung cancer accompanied by intrapulmonary metastasis andthree patients had been misdiagnosed with tuberculosis. The major CT manifestations were a cluster of nodules or masses located within 2 cm below the pleura and distributed along the bronchi. A total of nine patients had primary lesions with diameters of 1.1–2.0 cm and 12 patients had satellite lesions with diameters of 0.1–1.0 cm. Regarding treatment, 5 patients underwent surgical monotherapy, 12 patients underwent antifungal monotherapy and three patients received surgery in combination with antifungal therapy. HE staining indicated that Cryptococcus neoformans was engulfed by macrophages, which were surrounded by massive infiltrating lymphocytes and a large amount of fibrous tissue, which formed multinucleated macrophages or granulomas. Periodic acid-Schiff staining was positive and acid fast staining was negative. In conclusion, comparison of CT signs with the pathological manifestation of pulmonary cryptococcosis with multiple nodules or masses indicated that the pathological results may explain certain imaging signs. Combination of CT and pathological examination may provide a deeper understanding of this disease and improve the accuracy of its diagnosis.

Keywords: pulmonary cryptococcosis, lung cancer, tuberculosis, multi-slice spiral computed tomography, pathological

Introduction

Pulmonary cryptococcosis is a pulmonary fungal disease caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, an opportunistic pathogen, which may cause infection regardless of whether the body's immunity is low or not (1–3). Pulmonary neoformans with multiple nodules or mass is a type of primary pulmonary cryptococcosis; it is defined as a pulmonary disease caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, in which the number of intrapulmonary lesions is ≥2, the maximum nodule diameter is <3 cm and the maximum mass diameter is ≥3 cm (4–6). Due to the lack of typical signs on computed tomography (CT), the disease is prone to be misdiagnosed as lung cancer accompanied by intrapulmonary metastasis or tuberculosis. The present study was aimed at improving the understanding of this disease by comparing the CT signs with the pathological resultsin 20 patients and then using the pathological results to explain the CT signs.

Intrapulmonary metastasis of lung cancer manifests as multiple intrapulmonary nodules or masses with signs on CT including lobulation, irregular margins, spiculation, vascular convergence sign and pleural indentation (7–9). Pulmonary tuberculosis on CT manifests as multiple intrapulmonary nodules or masses presenting signs including irregular margins, satellite lesions and tree-in-bud sign (10,11). It is difficult to differentiate pulmonary cryptococcosis with multiple nodules or masses from lung cancer accompanied by intrapulmonary metastasis or pulmonary tuberculosis, which may lead to incorrect treatment. Since CT is non-invasive and reproducible, it is commonly used for evaluating lung diseases. Therefore, CT should be used to improve the accuracy of the diagnosis of this disease.

Patients and methods

The present study retrospectively enrolled 20 patients presenting with multiple nodules or masses on CT. They were selected from 68 patients with primary pulmonary cryptococcosis, who presented at three tertiary grade-A hospitals [The Second Affiliated Hospital of Qiqihar Medical College (Qiqihar), the Chinese PLA General Hospital (Beijing) and Beijing Shijitan Hospital (Beijing)] between January 2012 and December 2016. All of the 20 patients were pathologically confirmed to have primary pulmonary cryptococcosis. Of these, six underwent segmental or wedge resection of the lung and 14 underwent CT-guided percutaneous biopsy. The clinical data of the 20 patients, including the clinical manifestations, imaging signs, pathological results and treatment, were retrospectively analyzed. Histopathological images were utilized for diagnostic purposes. Since the present study was retrospective, the ethics committees of the three hospitals determined thatno informed consent was required from the patients.

Results

General patient information

The 20 patients included 14 males and 6 females with a mean age of 49.69 years (range, 27–78 years). The individual data for each patient are presented in Table I. Within the cohort, 6 patients had underlying diseases including diabetes, cancer, cirrhosis of the liver and pulmonary tuberculosis; furthermore, 1 patient had a history of exposure to birds. A total of 12 patients presented with symptoms, including an elevated temperature, cough, chest pain and abdominal pain, while the remaining 8 patients had no symptoms.

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with primary pulmonary cryptococcosis with multiple nodules or masses (n=20).

| No./age/gender | History | Symptoms | Location | Size (cm) | No. of nodules | CT presentation | CT primary diagnosis | Biopsy style | Pathology | Treatment | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/M/30 | Contact with birds | Cough, expectoration | RIL | Max: 1.9×1.7; around nodule: 1.6–2.0 | 3 | A near-pleural mass with clusters of round satellite lesions along bronchus, irregular margin, air bronchogram, halo sign around nodule, cavity | Infected lesions | Paracentesis | Granulomatous lesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, PAS (+) | Fluconazole for 20 months | Significant reduction and disappearance, no re-examination |

| 2/F/55 | Breast cancer surgery | Cough | RIL | Max: 5.2×3.6; around nodule: 1.1–1.5 | 4 | A near-pleural mass with clusters of round satellite lesions along bronchus, air bronchogram, lymphonodus (+) | Lung cancer with intrapulmonary metastasis | Paracentesis | Granulomatous lesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, lymph nodes exhibited reactive hyperplasia, PAS (+) | Fluconazole for 12 months | No re-examination |

| 3/M/54 | Hypertension | Stomachache | RIL+LUL | Max: 2.3×1.7; around nodule: 0.6–1.0 | 3 | A mass with clusters of round satellite lesions along bronchus, irregular margin, halo sign and air bronchogram | Granuloma | Paracentesis | Granulomatouslesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, PAS (+), acid fast stain (−) | Fluconazole for 9 months | Significant reduction and disappearance, no re-examination |

| 4/M/68 | Pulmonary tuberculosis | Chest pain | RUL | Max: 3.1×2.0; around nodule: 1.6–2.0 | 4 | A near-pleural mass with clusters of round satellite lesions along bronchus, irregular margin, long spicule, irregular calcification | Tuberculosis or lung cancer with intrapulmonary metastasis | Operation | Granulomatous lesions with necrosis, Cryptococcus and Candidain necrotic tissue, pulmonary interstitial lymphocytic infiltration PAS (+), acid fast stain (−) | Fluconazole for 3 months | No re-examination |

| 5/M/39 | Hypertension | Chest pain | LIL | Max: 3.2×1.8; around nodule: 0.6–1.0 | 5 | Three masses, clusters of distribution, with round satellite lesions along bronchus, some with lobulation, irregular margin, pleural indentation and cavity | Tuberculosis | Operation | Granulomatous lesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, PAS (+) | None | No recurrence |

| 6/M/78 | Hypertension | Elevated temperature, cough, chill | RIL | Max: 2.1×1.3; around nodule: 0.1–0.5 | 4 | A near-pleural mass with clusters of satellite lesions along bronchus, spicule | Infected lesions | Paracentesis | Granulomatous lesions without necrosis, Cryptococcus inmacrophages, PAS (+) | Fluconazole for 13 months | No recurrence |

| 7/M/45 | Reflux esophagitis | Chest pain | RIL | Max: 1.9×1.3; around nodule: 0.1–0.5 | 4 | A near-pleural mass with satellite lesions along bronchus, irregularmargin, air bronchogram, long spicule, pleural indentation, SUV 5.43 on PET-CT | Lung cancer with intrapulmonary metastasis | Operation | Granulomatous lesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, PAS (+), acid fast stain (−) | Fluconazole for 3 months | Unknown |

| 8/M/37 | None | Cough, expectoration | RUL+LIL | LIL: 3.0×2.2 RUL: 2.0×1.6 | 2 | LIL: Mass, irregular margin, lobulation, cavity, air bronchogram, long spicule; RUL: A mass with a nodule, irregular margin, air bronchogram, spicule | Infected lesions | Paracentesis | Granulomatous lesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, PAS (+) | Caspofungin, itraconazole for 15 days, fluconazole for 6 months | Significant reduction and disappearance, no re-examination |

| 9/M/65 | Hypertension | None | RML | Max: 2.0×1.6; around nodule: 0.6–1.0 | 4 | A nodule with clusters of satellite lesions along bronchus, lobulation, short spicule, air bronchogram, pleural indentation, lymphonodus (+) | Lung cancer with intrapulmonary metastasis | Operation | Granulomatous lesions, organized lesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, lymph nodes with reactive hyperplasia, PAS (+), acid fast stain (−) | None | No re-examination |

| 10/M/47 | Hypertension, diabetes | None | RUL+LIL | LIL-Max: 3.4×2.8; around nodule: 1.1–1.5 | 6 | LIL: A near-pleural mass with clusters of satellite lesions alongbronchus, irregular margin, lobulation, SUV9.3 in PET-CT; RUL: A nodule with lobulation, blood vessel convergence, SUV5.56 on PET-CT | Lung cancer with intrapulmonary metastasis | Paracentesis | Granulomatous lesions, organized lesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, PAS(+), acid fast stain (−) | Fluconazole for 10 months | No re-examination |

| 11/M/67 | Cirrhosis, spleen resection | None | LIL | Max: 1.0×0.7; around nodules: 0.1–0.5 | 4 | A near-pleural mass with clusters of satellite lesions along bronchus, air bronchogram, lobulation | Lung cancer with intrapulmonary metastasis | Paracentesis | Granulomatous lesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, PAS (+) | Fluconazole for 5 months | No re-examination |

| 12/F/38 | None | None | Whole lung | Max: 1.5×1.4; around nodule: 0.1–0.5 | 9 | Multiple nodules in the whole lung, particularly one nodule with clusters of satellite lesions along bronchus | Uncertain | Paracentesis | Granulomatous lesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, PAS (+) | Fluconazole for 6 months | No re-examination |

| 13/M/54 | None | None | RUL | Max: 1.1×0.8; around nodule: 0.1–0.5 | 3 | A nodule with clusters of satellite lesions along bronchus, irregular margin, long spicule, air bronchogram | Lung cancer with intrapulmonary metastasis | Operation | A solid region composed of hyperplastic fibrous tissue, granulomatouslesions, organized lesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, PAS (+), acid fast stain (−) | None | No re-examination |

| 14/F/30 | None | Cough | RML+RIL | Max: 2.1×2.0; around nodule: 0.6–1.0 | 4 | Two masses with clusters of satellite lesions along bronchus, one mass with halo sign, another with lobulation | Infected lesion | Paracentesis | Granulomatous lesions, organized lesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, PAS (+) | Fluconazole for 10 months | No re-examination |

| 15/M/51 | None | None | LIL | Max: 1.6×1.3; around nodules: 0.1–0.5 | 5 | A nodule with clusters of satellite lesions along bronchus, lobulation, spicule, pleural indentation, blood vessel convergence, calcification | Lung cancer with intrapulmonic metastasis | Operation | Granulomatous lesions with necrosis, Cryptococcus in necrotic tissue PAS (+), acid fast stain (−) | None | No re-examination |

| 16/F/44 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Elevated temperature | LIL | Max:1.3×1.2; around nodule: 0.6–1.0 | 3 | Three masses with clusters of round satellite lesions along bronchus, lobulation in certain instances, irregular margin, cavity, halo sign, blood vessel convergence | Infected lesion | Paracentesis | Granulomatous lesions, organized lesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, PAS (+) | Fluconazole for 13 months | Significant reduction and disappearance |

| 17/M/50 | None | None | RUL | Max: 2.5×1.6; around nodule: 1.1–1.5 | 8 | A near-pleural mass with clusters of satellite lesions along bronchus, lobulation in certain instances | Infected lesion | Paracentesis | Granulomatous lesions, Cryptococcus in macrophages, foam cells in alveolar space, PAS (+), acid fast stain (−) | Fluconazole for 5 months | No re-examination |

| 18/M/60 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | None | RML | Max: 1.7×1.5; around nodule: 0.1–0.5 | 6 | A mass with clusters of round satellite lesions along bronchus, some with lobulation, halo sign, blood vessel convergence | Infected lesion | Operation | Granulomatous lesions with necrosis, Cryptococcus and Candidain necrotic tissue, PAS (+), acid fast stain (−) | None | No re-examination |

| 19/F/27 | None | Chest pain | LIL | Max: 4.6×4.1; around nodule: 2.1–2.5 | 3 | Three near-pleural masses, cavity, lobulation in certain instances | Tuberculosis | Paracentesis | Granulomatous lesions with necrosis, Cryptococcus and Candidain necrotic tissue, PAS (+), acid fast stain (−) | Fluconazole for 9 months | No re-examination |

| 20/F/53 | Thyroid cancer surgery; radioiodine therapy | Cough | RIL+LIL | Max: 2.7×2.5; around nodule: 1.5–2.0 | 7 | Multiple round nodules of unequal size, air bronchogram | Pulmonary metastasis | Paracentesis | Granulomatous lesions, Cryptococcus and Candidain necrotic tissue, PAS (+), acid fast stain (−) | Fluconazole for 12 months | No re-examination |

PAS, periodic acid Schiff stain; CT, computed tomography; M, male; F, female; LUL, left upper lobe; RIL, right inferior lobe; RML, right middle lobe; PET, positron emission tomography; SUV, standardized uptake value.

CT examination

The site of the lesion on chest CT was the right upper lobe in 3 patients, the right middle lobe in 2 patients, the right lower lobe in 4 patients, the left lower lobe in 5 patients, the right upper lobe and left lower lobe in 2 patients, the right middle lobe and right lower lobe in 1 patient, the right lower lobe and left upper lobe in 1 patient, the right lower lobe and left lower lobe in 1 patient, as well as all lobes in 1 patient. The number of nodules or masses was 2–4 in 13 patients, 5–7 in 5 patients and 8–10 in 2 patients (Fig. 1). All primary lesions were located within 2 cm below the pleura. The diameter range of the lesions was 0.1–1.0 cm in 7 patients, 1.1–2.0 cm in 9 patients, 2.1–3.0 cm in 6 patients and >3.1 cm in 3 patients. The diameter range of the satellite lesions was 0.1–0.5 cm in 7 patients, 0.6–1.0 cm in 5 patients, 1.1–1.5 cm in 3 patients, 1.6–2.0 cm in 4 patients and >2.1 cm in 1 patient. Nodules were commonly round and distributed along the bronchi. They presented with lobulation (11/20), irregular margins (9/20), speculation (7/20), vascular convergence sign (4/20) and pleural indentation (4/20). A total of 8 patients were misdiagnosed with lung cancer accompanied by intrapulmonary metastasis; accompanying calcificationin 2 patients and cavities in 4 patients were also noted. A total of 3 patients were misdiagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis.

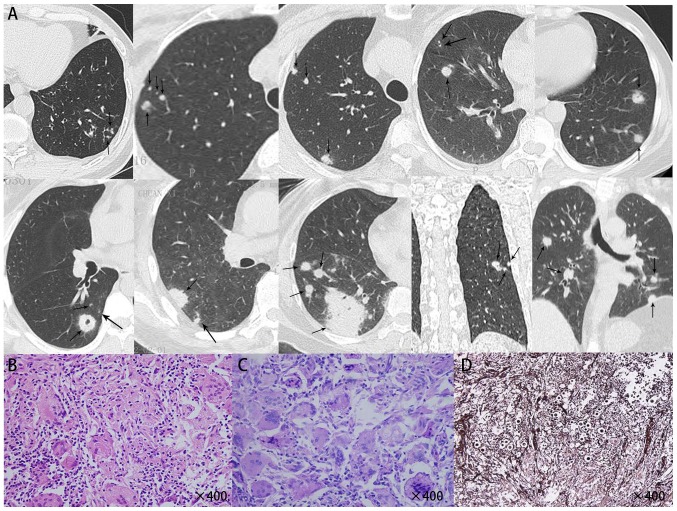

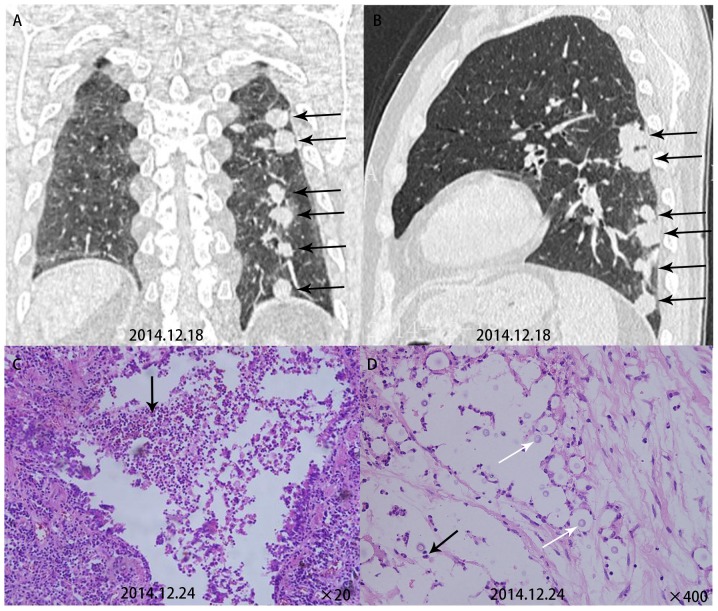

Figure 1.

(A) Computed to mography scans of various cases of primary pulmonary cryptococcosis exhibiting multiple intrapulmonary nodules and round satellite lesions distributed along the bronchial tract (two upper panels). (B) HE staining indicated that Cryptococcus neoformans was engulfed by macrophages, which were surrounded by massive infiltrating lymphocytes and a large amount of fibrous tissue, which formed multinucleated macrophages or granulomas (left lower panel, magnification, ×400). (C) Periodic acid-Schiff staining indicated a large number of purple-red Cryptococcus neoformans within multinucleated macrophages (middle lower panel magnification, ×400). (D) Giemsa staining indicated a large number of black Cryptococcus neoformans (right lower panel magnification, ×400).

Treatment and histopathological examination

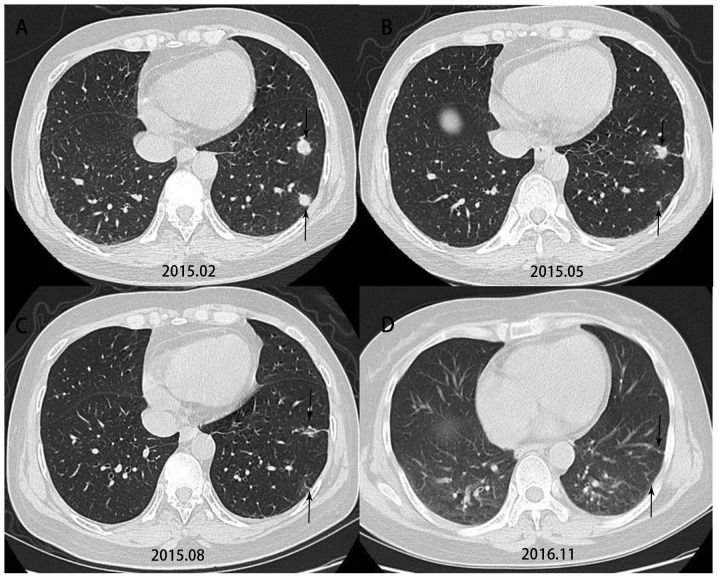

Based on the characteristics of their imaging data, 8 of the 20 patients underwent segmental or wedge resection of the lung and 12 underwent CT-guided percutaneous biopsy. All of them underwent histopathological examination. HE staining indicated that Cryptococcus neoformans-infested lesions were engulfed by macrophages (Fig. 1), and around them, a larger number of infiltrating lymphocytes were present, which formed multinucleated macrophages or granulomas, which were at times accompanied by coagulative necrosis. Specific staining indicatedthat the lesions wereperiodic acid-Schiff (+), Giemsa (+) andacid fast stain (−). A total of 5 patients underwent surgical monotherapy, 12 patients underwent antifungal monotherapy and three patients underwent surgery in combination with antifungal therapy. Voriconazole 200–400 mg/day was administered for treatment. The treatment period was 3–6 months in 6 patients, 6–12 months in 6 patients and >12 months in 3 patients. In Patient 16, the lesion shrank significantly after antifungal therapy (Fig. 2). Except for one patient whose follow-up result was unknown, noneof the other 19 patients had any recurrence at follow-up.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography indicated that the lesion shrank significantly in case no. 16, who received antifungal therapy and underwent a re-examination every three months.

Comparison of CT with histopathological results

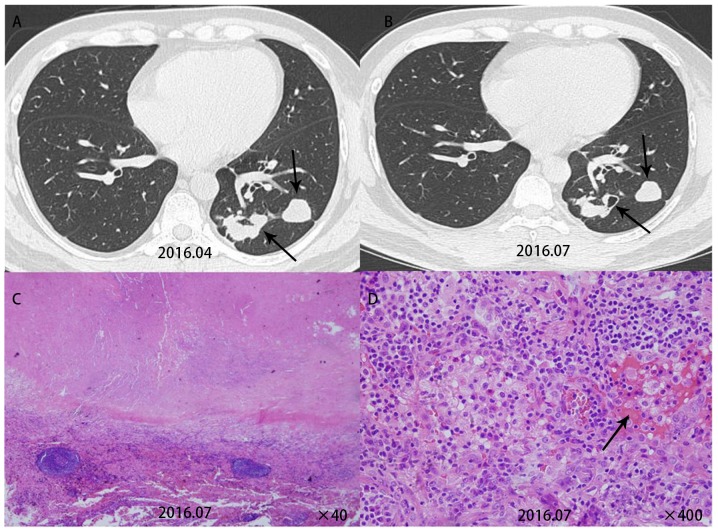

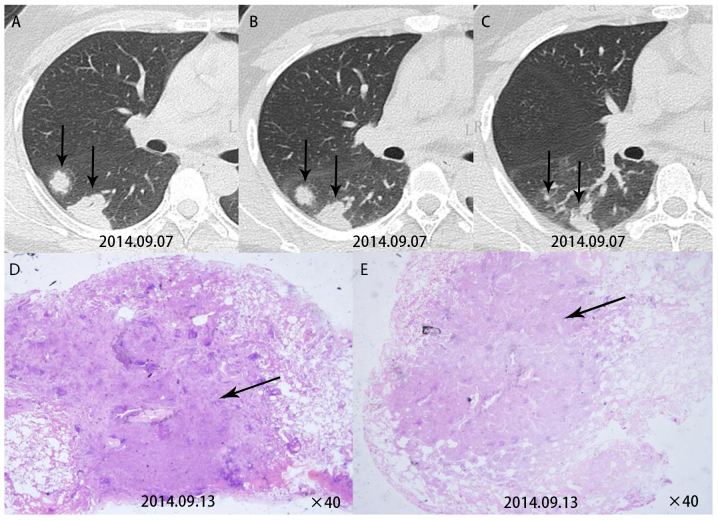

Comparison of CT signs with the pathological resultsindicated that it was possible to explain certain CT signs by the pathological results. Patient 5 had multiple nodules in the lower left lobe. A re-examination after three months revealed cavities in this patient. This patient was then given surgical treatment. Pathological examination for this patient revealed cryptococcal granuloma accompanied by coagulative necrosis and vasculitis formation (Fig. 3). Patient 7 had multiple subpleural nodules in the dorsal segments of the right lower lobe. A pathological examination for this patient revealed inflammatory granulomas near the pleura (Fig. 4). Patient 9 had multiple round nodules distributed along the bronchial tract. A pathological examination for this patient revealed free Cryptococcus neoformans in the bronchioles and lung alveoli (Fig. 5).

Figure 3.

(A) Case no. 5 had multiple nodules in the left lower lobe on computed tomography. (B) Re-examination after three months revealed cavities (arrow) in this patient (upper panel). (C) HE staining revealed inflammatory granuloma accompanied by coagulative necrosis (lower left panel, ×40). (D) Inflammatory cells were observed in the blood vessels, around which massive lymphocyte infiltration occurred, indicating vasculitis formation (arrow, lower right panel, ×400).

Figure 4.

(A, B and C, obtained from the same patient) Computed tomography revealed multiple subpleural nodules in the dorsal segments of the right lower lobe in case no 7. (D and E) HE staining indicated inflammatory granulomas near the pleura (arrows; lower panel, ×40).

Figure 5.

(A and B) Computed tomography in case no. 9 indicated multiple round subpleural nodules distributed along the bronchial tract in the left lobe (upper panel). (C) HE staining revealed a large number of inflammatory cells within the bronchioles (arrows; ×200) and traveling (D) Cryptococcus neoformans in the lung alveoli (white arrow), around which infiltrating inflammatory cells were present (arrow; lower left panel, ×400).

Discussion

As multislice CT is widely used, the detection rate of pulmonary cryptococcosis is increasing year by year, and mostinfected individuals are a population with abnormal immune function (12). In line with this, the present study also indicated that pulmonary cryptococcosis with multiple nodules frequently occurred in a population with normal immune function; 70% of the patients were males; 35% had underlying diseases or susceptibility factors and 60% had clinical symptoms.

Pulmonary cryptococcosis with multiple nodules has diverse CT signs (13) and it is prone to be misdiagnosed as lung cancer accompanied by intrapulmonary metastasis or tuberculosis. However, pulmonary cryptococcosis has certain unique characteristics: i) The lesion commonly occurs in the right lung; ii) a cluster of lesions is located within 2 cm below the pleura; iii) the primary lesion commonly has a diameter of 1.1–2.0 cm. Satellite lesions are usually smaller in diameter (commonly 0.1–1.0 cm). Round satellite nodules are distributed along the bronchial tract, and no tree-in-bud pattern is present; iv) cavities and calcification may be caused.

Comparison between CT signs and pathological results may enhance the understanding of how CT signs of the disease occur and gain a deeper understanding of the disease. Due to the small diameter of the spores of Cryptococcus neoformans (1–2 µm), they are prone to be inhaled to reach the bronchioles and terminal bronchioles (14), where they are engulfed by a large number of macrophages around the tracts below the bronchioles and within alveolar septa (15), to then form inflammatory granulomas below the pleura. Thus, a typical CT manifestation is characterized in that the lesion is mostly located within 2 cm below the pleura. After Cryptococcus neoformans enters the body, its capsule rapidly enlarges with its diameter reaching 4–10 µm order to withstand phagocytosis by macrophages. It travels freely in the bronchioles and lung alveoli and may be carried in streaming air to reach other parts of the lung during breathing, thereby causing bronchial dissemination. Furthermore, at the time that Cryptococcus neoformans is initially inhaled into the lungs, it may inhabit multiple sites of the lungs and then cause multiple lesions distributed along the bronchi. Pathology images have indicated that Cryptococcus neoformans may travel freely in lung alveoli and terminal bronchioles, which may be the cause of bronchial dissemination. Furthermore, inflammatory granulomas and fibrous tissue are formed after Cryptococcus neoformans is engulfed by macrophages. Fibrous tissues have contractile forces (16), so that the lesion appears rounded on CT, and the nodules are lobulated due to the unequal contractile forces. Cryptococcus neoformans may form a polysaccharide capsule as a protection against macrophage phagocytosis and may not produce any substances, including mucus, to block the bronchioles during the infection process (17). Thus, there was no tree-in-bud pattern on CT. The pathology images contained a large number of inflammatory cells around the blood vessels, whose infiltration resulted in vasculitis to ultimately cause coagulative necrosis. Therefore, cavities were observed on CT.

It is recommended that pulmonary cryptococcosis is treated with oral fluconazole for antifungal therapy (18,19). The regimen for fluconazole treatment is 200–400 mg/days for 3–6 months for asymptomatic patients, 6–12 months forpatients with mild to moderate symptoms and >12 months for patients with severe pulmonary infection. Antifungal therapy with fluconazole is not required for asymptomatic patients who have undergone surgery. For those with symptoms who have undergone surgery, fluconazole is administered at 200–400 mg/day for three months. According to our experience, fluconazole is the best choice for the treatment of this disease and there is no requirement for surgery.

In summary, pulmonary cryptococcosis with multiple nodules or masses frequently occurs below the pleura. The circular nodules distributed along the bronchi are mostly lobulated, and cavities and calcifications may be present. As pulmonary cryptococcosis is prone to being misdiagnosed as lung cancer or tuberculosis, the pathological results may be used to explain the CT signs so as to improve the understanding of this disease.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Qiqihar Medical University Scientific Research Funding Program (grant no. QY2016M-15), the Beijing Outstanding Young Talent Fund (grant no. 2014000021469G253), the National Natural Science Fund Youth Project (grant no. 81700007), the Railway Head Corporation (grant no. J2015C001-B) and the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (grant no. 2015ZX09J15105-004). The funders had no role in study design, datacollection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contribution

DW and XX conceived and designed the current study. CW, SZ, XM and JG were responsible for the collection and analysis of patient data. LF and YW collected the samples and performed parts of the experiments. Lei Pan performed the experiments and analyzed the results.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- 1.Kwon-Chung KJ, Fraser JA, Doering TL, Wang Z, Janbon G, Idnurm A, Bahn YS. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, the etiologic agents of Cryptococcosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4:a019760. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gates-Hollingsworth MA, Kozel TR. Serotype sensitivity of a lateral flow immunoassay for cryptococcal antigen. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20:634–635. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00732-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pappas PG. Cryptococcal infections in non-HIV-infected patients. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2013;124:61–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lackner M, de Hoog GS, Yang L, Moreno Ferreira L, Ahmed SA, Andreas F, Kaltseis M, Nagl M, Lass-Flörl C, Risslegger B, Rambach G, et al. Proposed nomenclature for Pseudallescheria, Scedosporium and related genera. Fungal Diversity. 2014;67:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s13225-014-0295-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coelho C, Bocca AL, Casadevall A. The intracellular life of cryptococcus neoformans. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:219–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kebede T, Reda N. Pulmonary cryptococ-coma mimicking pulmonary malignancy in an immunocompetent adult: A case report. Ethiop Med J. 2012;50:275–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McQuiston TJ, Williamson PR. Paradoxical roles of alveolar macrophages in the host response to Cryptococcus neoformans. J Infect Chemother. 2012;18:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10156-011-0306-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perfect JR, Bicanic T. Cryptococcosis diagnosis and a treatment: What do we know now. Fungal Genet Biol. 2015;78:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamakawa H, Yoshida M, Yabe M, Baba E, Okuda K, Fujimoto S, Katagi H, Ishikawa T, Takagi M, Kuwano K. Correlation between clinical characteristics and chest computed to-mography findings of pulmonary cryptococcosis. Pulm Med. 2015;2015:703407. doi: 10.1155/2015/703407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schweigert M, Dubecz A, Beron M, Ofner D, Stein HJ. Pulmonary infections imitating lung cancer: Clinical presentation and therapeutical approach. Ir J Med Sci. 2013;182:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s11845-012-0831-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hector A, Kirn T, Ralhan A, Graepler-Mainka U, Berenbrinker S, Riethmueller J, Hogardt M, Wagner M, Pfleger A, Autenrieth I, et al. Microbial colonization and lung function in adolescents with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2016;15:340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Hoz RM, Pappas PG. Cryptococcal infections: Changing epidemiology and implications for therapy. Drugs. 2013;73:495–504. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tseng HK, Liu CP, Ho MW, Lu PL, Lo HJ, Lin YH, Cho WL, Chen YC, Taiwan Infectious Diseases Study Network for Cryptococcosis Microbiological, epidemiological, and clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with cryptococcosis in Taiwan, 1997–2010. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaragoza O, Rodrigues ML, De Jesus M, Frases S, Dadachova E, Casadevall A. The capsule of the fungal pathogen Cryptocoecus neoformans. Adv Appl Miembiol. 2009;68:133–216. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(09)01204-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma H, May RC. Virulence in cryptococcus species. Adv Appl Micmbiol. 2009;67:131–190. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(08)01005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie X, Xu B, Yu C, Chen M, Yao D, Xu X, Cai X, Ding C, Wang L, Huang X. Clinical analysis of pulmonary cryptococcosis in non-hiv patients in south china. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:3114–3119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang CC, Sorrell TC, Chen SC. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:681–691. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1562895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brizendine KD, Baddley JW, Pappas PG. Predictors of mortality and differences in clinical features among patients with Cryptococcosis according to immune status. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perfect JR. Fungal diagnosis: How do we do it and can we do better? Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;4(Suppl 29):1–11. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.761134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.