Abstract

Interleukin 10 (IL-10) is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that plays a critical role in the control of immune responses. However, its mechanisms of action remain poorly understood. Here, we show that IL-10 opposes the switch to the metabolic program induced by inflammatory stimuli in macrophages. Specifically, we show that IL-10 inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced glucose uptake and glycolysis and promotes oxidative phosphorylation. Furthermore, IL-10 suppresses mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity through the induction of an mTOR inhibitor, DDIT4. Consequently, IL-10 promotes mitophagy that eliminates dysfunctional mitochondria characterized by low membrane potential and a high level of reactive oxygen species. In the absence of IL-10 signaling, macrophages accumulate damaged mitochondria in a mouse model of colitis and inflammatory bowel disease patients, and this results in dysregulated activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and production of IL-1β.

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is a key anti-inflammatory cytokine produced by activated immune cells (1). Although most hematopoietic cells sense IL-10 via expression of IL-10 receptor (IL-10R), recent studies have shown that macrophages are the main target cells of the inhibitory IL-10 effects (2, 3). Polymorphisms in the Il10 locus confer risk for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease (4, 5), and mice and humans deficient in either IL-10 or IL-10R exhibit severe intestinal inflammation (2,3,6, 7), indicating that the IL-10-IL10R axis plays an essential role in regulation of intestinal tissue homeostasis and prevention of IBD. Little is known about the molecular basis of the anti-inflammatory activities of IL-10 (8). Understanding the role of IL-10 in the regulation of metabolic processes is essential both for deciphering how IL-10 acts to control inflammatory responses and for discovering key molecular regulators controlling processes involved in resolution of inflammation.

Inflammatory response is generally triggered by receptors of the innate immune system, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (9). The initial recognition of infection is mediated mainly by tissue-resident macrophages, which lead to the production of inflammatory mediators. Recent studies of cellular metabolism in macrophages have shown profound alterations in metabolic profiles during macrophage activation (10–12). For example, macrophages activated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) undergo metabolic changes toward glycolysis, whereas macrophages activated with IL-4 commit to oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) (13, 14), and both suggest that metabolic adaptation during macrophage activation is a key component of macrophage polarization, instrumental to their function in inflammation and tissue repair.

Results

IL-10–deficient macrophages exhibit altered metabolic profiles after LPS stimulation

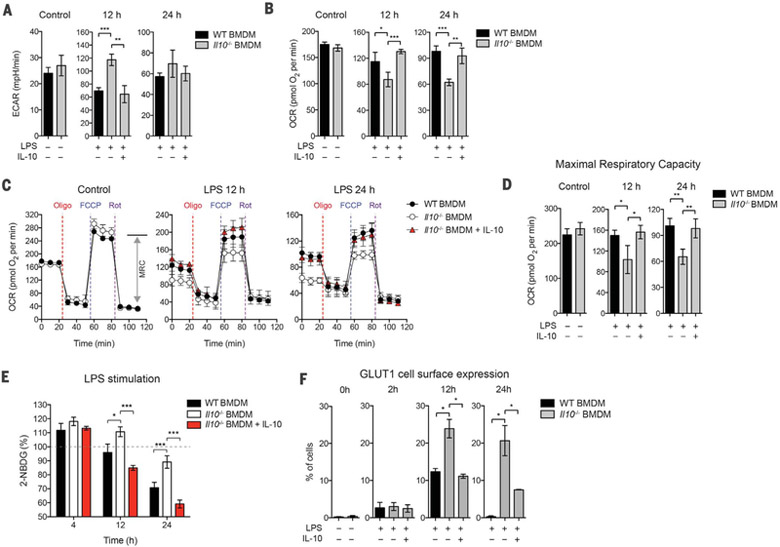

We analyzed Il10−/− bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs), for changes in the rate of extracellular acidification (ECAR), and the mitochondrial rate of oxygen consumption (OCR), as a measure of glycolysis and OXPHOS, respectively, after LPS stimulation. Il10−/− BMDMs became more glycolytic (i.e., had higher basal ECAR) but less “oxidative” (i.e., had lower basal OCR) as compared with wild-type (WT) BMDMs (Fig. 1, A and B). The reduced OXPHOS in Il10−/− cells was not due to nitric oxide (NO) production, because treatment with inhibitors of inducible nitric oxide synthase failed to rescue the phenotype (fig. S1). However, addition of exogenous IL-10 restored the WT phenotype in Il10−/− cells (Fig. 1, A and B), whereas the treatment of WT BMDMs with a blocking antibody against the IL-10R alpha subunit (IL-10Rα) resulted in altered profiles of ECAR and OCR similar to that in Il10−/− cells (fig. S2), indicating an autocrine effect of IL-10 in macrophages. The exaggerated glycolysis was also seen in splenic macrophages from Il10−/− mice injected intraperitoneally with LPS (fig. S3A). We next assessed the functional profile of mitochondria by determining real-time changes in OCR during sequential treatment of cells with oligomycin [adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthase inhibitor], the cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenyl-hydrazone (FCCP) (H+ ionophore), and rotenone (inhibitor of the electron-transport chain) (Fig. 1C). The absence of exogenous IL-10 in Il10−/− BMDMs after LPS stimulation resulted in a lower maximal respiratory capacity (MRC) compared with WT BMDMs (Fig. 1, C and D). These results suggest that the reduced basal OCR observed in Il10−/− BMDMs after LPS stimulation could be due to the loss of mitochondrial fitness, as indicated by the reduced MRC. Consistent with this idea, basal cellular ATP levels were also reduced in Il10−/− BMDMs after LPS stimulation (fig. S4).

Fig. 1. IL-10 regulates glycolysis and mitochondrial function in BMDMs on LPS stimulation.

WT or Il10−/− BMDMs were stimulated without (control) or with LPS in the presence or absence of IL-10 for indicated times. (A and B) ECAR and OCR in BMDMs as assessed by Seahorse assay. (C) Real-time changes in the OCR of BMDMs after treatment with oligomycin (Oligo), FCCP, and rotenone (Rot). MRC, maximal respiratory capacity (double-headed arrow), is shown for the control in WT BMDMs. (D) Maximal respiratory capacity of BMDMs measured by real-time changes in OCR. (E) Glucose uptake of BMDMs determined by direct incubation with 2-NBDG (a fluorescent D-glucose analog) for 2 hours, followed by fluorescence detection. (F) Quantification of GLUT1 plasma membrane translocation using ImageStream. Percentage of cells with GLUT1 cell surface translocation was determined by colocalized GLUT1 (green) and CD11b (red) as shown in the representative images (see fig. S5E). All values are means ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Student’s t test (unpaired); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

IL-10 inhibits glycolytic flux

We next asked whether the inhibition of glycolysis by IL-10 is due to suppression of glycolytic flux. Consistent with previous studies (15), glucose uptake increased and reached a maximum within 2 hours of LPS stimulation and decreased after 12 hours in WT BMDMs (fig. S5A). Glucose uptake was also observed in LPS-stimulated Il10−/− BMDMs at 4 hours (Fig. 1E). However, after 12 hours of LPS stimulation in the absence of exogenous IL-10, glucose uptake was maintained at higher levels in Il10−/− cells (Fig. 1E), which indicates that IL-10 has an inhibitory effect on glucose uptake.

The glucose transporter GLUT1 plays an important role in glucose uptake in macrophages during LPS stimulation (15). Indeed, our RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data showed that BMDMs predominantly expressed Glut1 at the steady state (fig. S5B). However, the expression of Glut1 was not affected by IL-10 (fig. S5C). We therefore asked whether IL-10 inhibited GLUT1 translocation from intracellular vesicles to the cell surface, which is a key step to facilitate glucose uptake into the cell. To test this, we tracked the cellular localization of GLUT1 with an antibody and visualized this through immunofluorescence and ImageStream analysis. Both analyses showed that GLUT1 was mainly localized in intracellular vesicles at the steady state but translocated to the plasma membrane after LPS stimulation (Fig. 1F and fig. S5, D and E). Note that exogenous IL-10 inhibited the GLUT1 translocation in Il10−/− BMDMs (Fig. 1F and fig. S5D). In addition, RNA-seq analysis in Il10−/− BMDMs also revealed that IL-10 inhibited the expression of genes encoding enzymes in the glycolytic pathway, including Hk1, Hk3, Pfkp, and Eno2 (fig. S5F). Together, these data illustrate that IL-10 inhibits glycolytic flux by means of regulating the GLUT1 translocation and the gene expression of glycolytic enzymes.

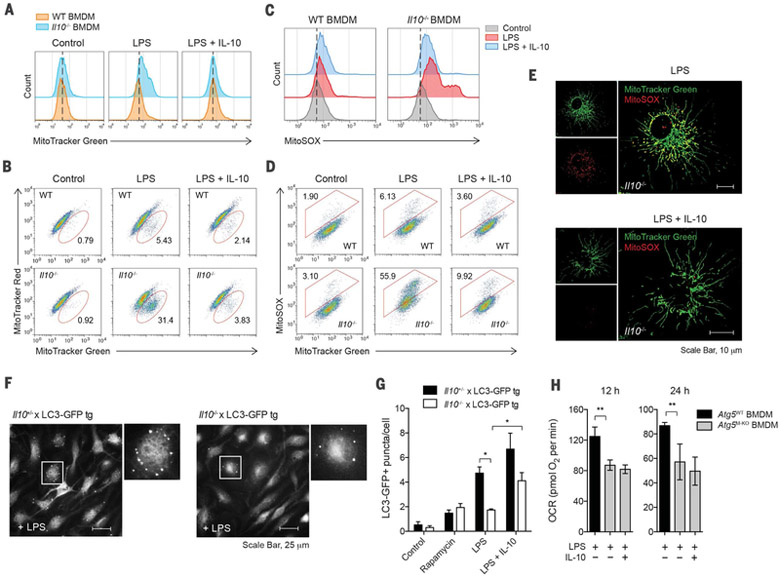

IL-10 prevents accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria

To investigate whether the altered metabolic profiles of mitochondria described above in Il10−/− BMDMs resulted from abnormal mitochondrial function, we first stained cells with MitoTracker Green for total mitochondrial content, regardless of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), and found that Il10−/− BMDMs had increased mitochondrial mass after LPS stimulation, compared with WT macrophages (Fig. 2A). This was not due to increased cell size, because Il10−/− cells had a size similar to that of WT cells, but rather was correlated with greater intracellular complexity reflected by the side scatter (SSC) signal measured by flow cytometry (fig. S6). We then hypothesized that the increase in mitochondrial mass in Il10−/− cells could be due to accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria with loss of Δψm. To test this, we used a combination of MitoTracker Green (Δψm-independent mitochondrial stain) with MitoTracker Red (Δψm-dependent mitochondrial stain) to distinguish between respiring mitochondria and dysfunctional mitochondria (16), and we observed an increase in dysfunctional mitochondria (MitoTracker Green+high, MitoTracker Red+low) in LPS-stimulated Il10−/− BMDMs (Fig. 2B). This is in line with the loss of Δψm observed by using tetramethyl rho-damine methyl ester staining (fig. S7). These data suggested that accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria occurred during LPS stimulation in the absence of IL-10.

Fig. 2. IL-10 prevents accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and production of mitochondrial ROS via the induction of mitophagy.

(A to E) WT or Il10−/− BMDMs stimulated without (control) or with LPS in the presence or absence of IL-10 for 24 hours. Total mitochondrial mass was analyzed by flow cytometry in cells labeled with MitoTracker Green (A). Mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) and ROS were analyzed in cells labeled with MitoTracker Green and MitoTracker Red (B), or with MitoSOX (C) and (D), respectively. Representative microscopic images show mitochondrial ROS production in Il10−/− BMDMs labeled with MitoTracker Green and MitoSOX (E). Scale bars, 10 μm. (F and G) Quantification of LC3-GFP punctate formation in IL-10–sufficient (Il10+/−) or –deficient (Il10−/−) LC3-GFP tg BMDMs stimulated as in (A) or with rapamycin for 6 hours. Representative microscopic images show LC3-GFP punctate in higher magnification of the indicated area (box) (F). Quantification based on counting LC3-GFP punctate per cell in the field of view (G). (H) OCR in BMDMs generated from Atg5flox/flox (Atg5WT) or Atg5flox/flox LysM-Cre (Atg5M–KO) mice and stimulated as in (A) for the indicated times. All values are means ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Student’s t test (unpaired); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Loss of Δψm is known to be associated with accumulation of mitochondrial ROS (17). We therefore examined whether accumulation of Δψmlow mitochondria in Il10−/− BMDMs was associated with production of mitochondrial ROS. To assess ROS levels in the mitochondria, we used the mitochondria-specific ROS indicator MitoSOX to selectively detect superoxide in the mitochondria of live cells. We found that MitoSOX fluorescence was enhanced in LPS-stimulated Il10−/− macrophages in the absence of exogenous IL-10 (Fig. 2C) and correlated with total mitochondrial mass as indicated by MitoTracker Green staining (Fig. 2D), and these findings suggest that the absence of IL-10 leads to ROS production from accumulated mitochondria. The accumulation of ROS-producing mitochondria in Il10−/− cells was also visualized by live-cell imaging using both fluorescent dyes (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, the ROS production in Il10−/− macrophages was of mitochondrial origin as it could be blocked by treatment with inhibitors of mitochondrial complex II (fig. S8).

IL-10 promotes the induction of autophagy

We hypothesized that the accumulation of dysfunctional and ROS-producing mitochondria could be the result of impaired mitophagy in Il10−/− cells after LPS stimulation. To detect mitophagy, we overexpressed mitochondrial targeting fusion protein (Mito-DsRed) in BMDMs generated from LC3-GFP transgenic (tg) mice that expressed green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged LC3 (18) and observed increased recruitment of LC3-GFP to Mito-DsRed+ mitochondria in LPS-stimulated cells (fig. S9), suggesting an induction of mitophagy during LPS stimulation. To determine more precisely the role of IL-10 in mitophagy, we crossed LC3-GFP transgenic mice with Il10−/− mice and generated Il10−/− LC3-GFP BMDMs. Autophagy was assessed by measuring LC3-GFP puncta formation after LPS stimulation as illustrated in Fig. 2F. As expected, regardless of IL-10 deficiency, both Il10+/− and Il10−/− BMDMs with LC3-GFP had increased formation of LC3 puncta after treatment with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin, which is known to induce autophagy (Fig. 2G). However, in the absence of exogenous IL-10, Il10−/− LC3-GFP cells had significantly lower LC3 puncta formation after LPS stimulation as compared with control cells (i.e., Il10+/−) (Fig. 2G), suggesting an induction of mitophagy by IL-10 in macrophages after LPS stimulation. Consistent with this idea, BMDMs lacking Atg5 also exhibited a significantly altered metabolic profile in OCR (Fig. 2H). However, unlike in Il10−/− BMDMs, addition of exogenous IL-10 failed to restore WT phenotypes in Atg5-deficient cells (Fig. 2H), suggesting that the effect of IL-10 on mitochondrial functions is largely, but perhaps not exclusively, autophagy-dependent.

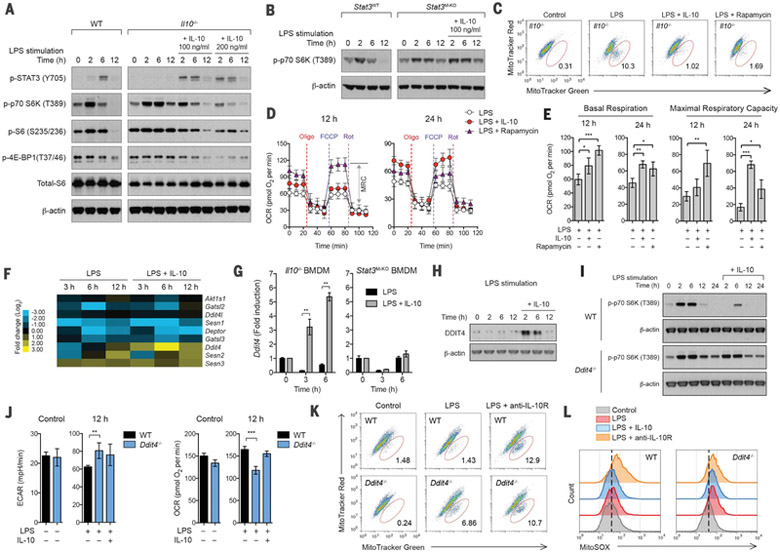

IL-10 maintains mitochondrial integrity and function via inhibition of mTOR

mTOR is a key metabolic regulator, and the activation of mTORC1 controls glucose and lipid metabolism and inhibits autophagy (19). Given the observed effects of IL-10 on mitophagy, we examined whether IL-10 regulates the activity of the mTORC1 pathway. In support of the idea that mTORC1 might coordinate metabolic changes during macrophage activation, stimulation of WT BMDMs with LPS resulted in mTORC1 activation above the basal level, as indicated by increased phosphorylation of the downstream targets such as S6K, S6, and 4E-BP1, which reached maximal levels in 2 hours and was strongly suppressed after 6 hours (Fig. 3A). This tightly regulated mTORC1 activation was impaired in Il10−/− BMDMs where higher and prolonged activation was observed during LPS stimulation (Fig. 3A). Addition of exogenous IL-10 to these cells was again able to restore the regulation observed in WT cells (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, prolonged mTORC1 activation was also observed in BMDMs lacking STAT3, a key transcription factor downstream of IL-10R signaling, and it was not rescued by adding exogenous IL-10 (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that IL-10 signaling via STAT3 inhibits mTORC1 activation. In addition, IL-10 inhibited the phosphorylation of Akt targets proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa (PRAS40) and mTOR and, consistent with a previous report (20), IL-10 increased phosphorylation of adenosine 5′-monophosphate–activated kinase (AMPK) (fig. S10).

Fig. 3. Induction of DDIT4 by IL-10 inhibits mTOR signaling and maintains mitochondrial fitness.

BMDMs of the indicated strains were stimulated without (control) or with LPS in the presence or absence of IL-10, rapamycin, or antibody against IL-10Rα (anti-IL-10R) for 24 hours or the indicated times. (A and B) Comparison of mTORC1 activation in WT and Il10−/− BMDMs (A) or Stat3flox/flox (Stat3WT) and Stat3flox/flox LysM-Cre (Stat3M–KO) BMDMs (B) was analyzed by Western blotting. (C) Mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) was analyzed in Il10−/− BMDMs labeled with MitoTracker Green and MitoTracker Red. (D) Real-time changes in the OCR of Il10−/− BMDMs after treatment with oligomycin, FCCP, and rotenone were assessed by Seahorse assay. MRC, maximal respiratory capacity (double-headed arrow), is shown for rapamycintreated Il10−/− BMDMs at 12 hours. (E) Basal respiration and maximal respiratory piratory capacity of Il10−/− BMDMs, measured by real-time changes in OCR. (F) Heat map showing RNA-seq data, log2 (fold change) of a selected subset of genes encoding negative regulators of mTORC1 activation in Il10−/− BMDMs. (G) Induction of Ddit4 mRNA expression by IL-10 in Il10−/− or Stat3M–KO BMDMs was analyzed by quantitative PCR. Data are expressed as fold change. (H) Induction of DDIT4 protein expression by IL-10 in Il10−/− BMDMs. (I) Comparison of mTORC1 activation in WT and Ddit4−/− BMDMs. (J) ECAR and OCR in WT and Ddit4−/− BMDMs. (K and L) Δψm and mitochondrial ROS were analyzed in WT and Ddit4−/− BMDMs labeled with MitoTracker Green and MitoTracker Red (K) or with MitoSOX (L). All values are means ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Student’s t test (unpaired); **P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. *** P < 0.001.

We next tested whether the inhibition of mTOR by IL-10 was responsible for maintaining mitochondrial integrity and function during LPS stimulation, which otherwise could lead to accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria as seen in Il10−/− BMDMs. We treated Il10−/− BMDMs with rapamycin to directly inhibit mTOR during LPS stimulation and assessed their mitochondrial content and oxygen consumption. The effect of rapamycin treatment was similar to that with exogenous IL-10 in which it inhibited accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria with loss of Δψm (Fig. 3C) and enhanced basal respiration and MRC (Fig. 3, D and E) in Il10−/− cells. In addition, rapamycin treatment also reduced ECAR in Il10−/− cells during LPS stimulation (fig. S11A), and this suggests that IL-10 suppresses glycolysis via inhibiting mTOR, although IL-10 might also act through an unknown process to regulate GLUT1 translocation (fig. S11B).

Induction of DDIT4 by IL-10 inhibits mTOR signaling

We next sought to define how IL-10 inhibits mTOR signaling. Because the inhibition is STAT3-dependent (Fig. 3B), the mechanism should require transcription. Therefore, we performed RNA-seq analysis and examined if IL-10 transcriptionally regulates metabolic pathways, which would lead to the inhibition of mTOR signaling. It is noteworthy that we found that IL-10 regulated a subset of genes known to participate in the upstream signaling of mTORC1 (fig. S12, A and B). The regulation of these genes might have collective effects on suppressing mTOR signaling (fig. S12C). However, the abundant and stable protein levels of their gene products in BMDMs before and after LPS stimulation (as shown in fig. S12D) lead us to hypothesize that the inhibition of mTOR signaling by IL-10 could be mediated via an active suppression by negative regulators. We therefore focused on known negative regulators of mTOR signaling (21–25) and examined their gene expression. Among those genes, we found that Ddit4 was strongly induced by IL-10 during LPS stimulation (Fig. 3, F and G, and fig. S13). This up-regulation was also confirmed at the protein level (Fig. 3H), and it required the transcription factor STAT3 (Fig. 3G) but not the hypoxia-inducible factor HIF-1α (data not shown), a known regulator of Ddit4 in response to hypoxia (26).

To assess the role of DDIT4 in macrophages, we generated BMDMs from Ddit4−/− mice and stimulated them with LPS. Cells lacking DDIT4 had prolonged mTORC1 activation during LPS stimulation (fig. S14A), a phenotype similar to that we observed in Il10−/− BMDMs. However, unlike in WT cells, treatment with exogenous IL-10 failed to inhibit mTORC1 activation in Ddit4−/− cells (Fig. 3I), and this suggests that the inhibition of mTOR signaling by IL-10 is DDIT4-dependent. Furthermore, similar to cells lacking IL-10 signaling (i.e., treatment with IL-10Rα blocking antibody), Ddit4−/− BMDMs exhibited a significant alteration in the profiles for ECAR and OCR (Fig. 3J) and accumulated dysfunctional mitochondria with loss of Δψm and with enhanced ROS production after LPS stimulation (Fig. 3, K and L). Treatment with exogenous IL-10 had minimal effect on reversing the phenotypes, and this indicated that DDIT4 is a critical target of IL-10 signaling. Together, these observations suggest that the inhibition of mTOR signaling by IL-10 via DDIT4 plays an essential role in mitochondrial clearance in macrophages after LPS stimulation. In line with this idea, overexpression of DDIT4 in Il10−/− BMDMs was able to restore the inhibitions of mTOR signaling and accumulation of damaged mitochondria (fig. S14, B to E).

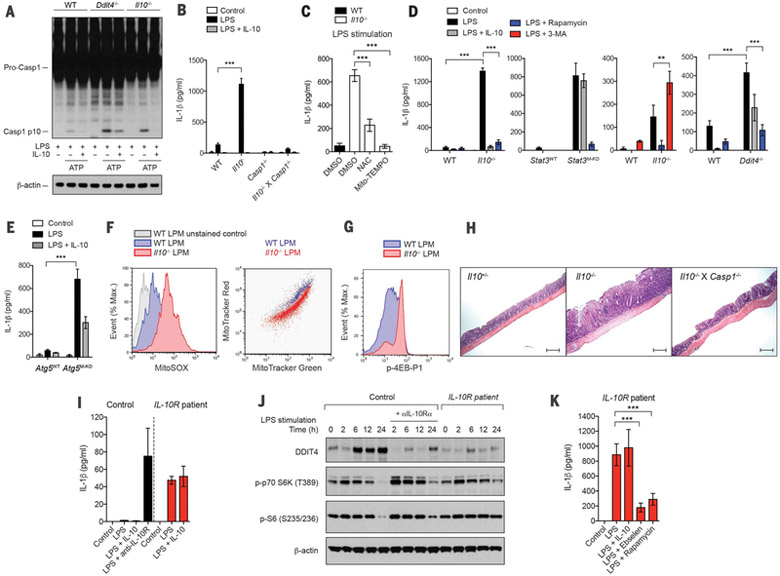

IL-10 negatively regulates inflammasome activation via inhibition of mTOR

We next assessed the roles of metabolic control by IL-10 in inflammatory responses. Mitochondria have emerged as signaling organelles that contribute to certain innate immune pathways, including inflammasome activation and RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) signaling (17). We utilized a two-signal model for NLRP3 inflammasome activation, where BMDMs were primed with LPS (signal 1) and then stimulated with ATP (signal 2). We found that both Il10−/− and Ddit4−/− BMDMs exhibited enhanced caspase-1 cleavage, and treatment of Il10−/− cells, but not Ddit4−/− cells, with IL-10 resulted in minimal caspase-1 cleavage (Fig. 4A and fig. S15A), suggesting that IL-10 inhibits caspase-1-dependent inflammasome activation via induction of DDIT4. Even in the absence of signal 2 (i.e., ATP), stimulation with LPS in cells lacking IL-10 or STAT3 was sufficient to trigger IL-1β secretion, which otherwise was minimal in WT cells (Fig. 4, B and D). The secretion of IL-1β was caspase-1-dependent (Fig. 4B), indicating that the IL-1β secretion in Il10−/− BMDMs was due to inflammasome activation. In addition, IL-10 inhibited inflammasome activation independently of any effect on Nlrp3 transcription, as overexpression of NLRP3 did not overcome the inhibition (fig. S15B). We then hypothesized that enhanced mitochondrial ROS production in Il10−/− cells might serve as an endogenous signal 2 for inflammasome activation. In support of this, treatment of Il10−/− cells with the antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) or mitochondrial ROS inhibitor Mito-TEMPO was able to inhibit the IL-1β secretion (Fig. 4C). The effect of the ROS inhibitor on inflammasome activation rather than expression of pro-IL-1β was also confirmed in Il10−/− cells overexpressing pro-IL-1β where IL-1bβ secretion was inhibited by antioxidants (fig. S15C). Consistent with this, Mito-TEMPO had no effect on gene expression of pro-IL-1β in Il10−/− cells during LPS stimulation (fig. S16).

Fig. 4. Aberrant activation of inflammasome via mTOR signaling and mitochondrial ROS production in macrophages from IL-10–deficient mice and IBD patients with loss of IL-10R signaling.

(A) The cleavage of caspase-1 to its active p10 subunit in WT, Ddit4−/−, or Il10−/− BMDMs primed with LPS for 12 hours and stimulated with ATP for 30 min. (B to E) IL-1β secretion by BMDMs of the indicated strains stimulated without (control) or with LPS in the absence or presence of IL-10, NAC, Mito-TEMPO, rapamycin, or 3-MA for 24 hours was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. (F and G) Mitochondrial ROS, mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), and phosphorylation of 4EB-P1 in colonic lamina propria cells, isolated from WT or Il10−/− mice and labeled with MitoSOX [(F) left] or with MitoTracker Green and MitoTracker Red [(F) right] or stained intracellularly for phosphorylated 4EB-P1 (G) were analyzed by flow cytometry gated on CD11b+ for lamina propria macrophages (LPMs). (H) Representative immunohistochemistry images of hematoxylin and eosin staining in middle-colon tissue from the indicated mouse strains. Scale bar, 200 μm. (I) IL-1β secretion by monocytederived macrophages (MDMs) from IL-10R–deficient patients versus healthy subjects, stimulated without (control) or with LPS in the absence or presence of IL-10 or antibody against IL-10Rα (anti-IL-10R) for 24 hours. (J) Comparison of DDIT4 expression and mTORC1 activation in MDMs from IL-10R–deficient patients versus healthy subjects was analyzed by Western blotting. MDMs were stimulated as in (I) for the indicated times. (K) The effect of inhibition of ROS and mTORC1 on IL-1β secretion by MDMs from IL-10R–deficient patients and stimulated as in (I) in the absence or presence of ebselen or rapamycin for 24 hours. All values are means ± SD of at least three independent experiments (A to H) or two independent experiments (I to K). Student’s t test (unpaired); **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

We next tested if treatment with rapamycin, the autophagy inhibitor 3-MA, or the autophagy activator AICAR or overexpression of DDIT4 has any impact on the aberrant IL-1β secretion in Il10−/− cells. IL-1β secretion was inhibited by rapamycin and AICAR but enhanced by 3-MA in cells lacking IL-10 or STAT3 (Fig. 4D and figs. S14F and S15D) or Il10−/− cells overexpressing pro-IL-1β (fig. S15C). Autophagy is known to inhibit inflammasome activation (27). Collectively, these data suggest that the induction of mitophagy by IL-10 via inhibition of mTOR contributes to the suppression of inflammasome activation. In agreement with this, the effect of IL-10 on inhibiting IL-1β secretion was significantly reduced in Atg5-deficient BMDMs (Fig. 4E). Because autophagy deficiency can lead to ROS-dependent amplification of RLR signaling (16), we also tested whether IL-10 inhibits RLR signaling. Indeed, Il10−/− BMDMs stimulated with poly(I:C) complexed to lipofect-amine exhibited enhanced type I interferon response, and treatment with NAC or exogenous IL-10 inhibited the enhanced response (fig. S17, A to C).

Aberrant activation of macrophage inflammasome in IL-10–deficient mice and IL-10R–deficient IBD patients

We have previously shown that gut bacteria sensing through MyD88 in intestinal macrophages drive colitis in IL-10-deficient mice (28). To test our current model in vivo, we isolated colonic lamina propria cells from Il10−/− mice with severe colitis and assessed mitochondrial content and mTOR signaling in lamina propria macrophages (LPMs). Similar to LPS-stimulated Il10−/− BMDMs, LPMs from Il10−/− mice had higher mitochondrial ROS, accumulated mitochondria with loss of Δψm (Fig. 4F), and increased activation of mTORC1 (Fig. 4G); these findings suggest that, in the absence of IL-10, mitochondrial ROS production due to increased mTOR signaling in LPMs contributes to the development of colitis via inflammasome activation. Consistent with this idea, mice lacking both IL-10 and caspase-1 had significantly reduced pathology of colitis compared with mice lacking IL-10 only (Fig. 4H and fig. S15, E to G). Finally, we found that monocyte-derived macrophages from IBD patients with a null mutation in the IL-10R gene also exhibited aberrant secretion of IL-1β (Fig. 4I), reduced DDIT4 expression, and prolonged mTORC1 activation (Fig. 4J). Furthermore, inhibition of ROS or mTOR signaling by antioxidants or rapamycin, respectively, suppressed IL-1β secretion in these cells (Fig. 4K). Collectively, these data suggest that IL-10 prevents development of colitis, at least in part, through inhibition of mTOR signaling and inflammasome activation in macrophages via elimination of dysfunctional mitochondria.

Discussion

Macrophage activation is a key event in the inflammatory response. Activated macrophages undergo profound reprogramming of their cellular metabolism. Here we provide evidence for IL-10-dependent regulation of metabolic processes in activated macrophages and suggest that IL-10 acts to inhibit inflammatory responses in part by controlling essential metabolic pathways, including mTOR signaling.

The importance of glycolysis in the inflammatory response of macrophages has been demonstrated in a previous study, where inhibition of glycolysis using 2-deoxyglucose decreases the inflammatory response (29). Our data showing the inhibition of glycolysis by IL-10 by suppression of glucose uptake and glycolytic gene expression suggest that IL-10 might act to reverse the metabolic program associated with the inflammatory response. This is consistent with the anti-inflammatory function of IL-10 and also in line with observations from T cells, where glycolysis is needed for T helper cell TH17 function (the inflammatory lymphocyte), but if this is blocked, then the T cells become anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells (30).

Mitochondria have emerged as central organelles that integrate metabolism and inflammatory responses. Here we show that, upon LPS activation, IL-10-deficient macrophages had further reduced OXPHOS as compared with the already reduced OXPHOS in control macrophages. Although this could be due to excessive production of NO in IL-10-deficient cells, because NO is known to inhibit OXPHOS (31, 32), our analysis using treatment with inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibitors shows a NO-independent effect of IL-10 on OXPHOS (fig. S1). Rather, our findings showing that IL-10 promotes the induction of mitophagy suggest that IL-10 plays a more direct role in maintaining mitochondrial fitness, which is key to preserving respiratory capacity. In addition, IL-10 signaling via STAT3 may have a direct effect on improving mitochondrial function, as it has been shown previously that activated STAT3 is present in mitochondria and is required for optimal function of the electron transport chain (33).

It is increasingly recognized that mTOR acts as a central regulator of cellular metabolism (34). Here we show that IL-10 inhibits mTORC1 activation via STAT3; this suggests that IL-10 controls metabolic processes via engaging the regulation of mTOR signaling. These findings support our observations described above in several ways. First, mTOR signaling is critical to mediate the switch from OXPHOS to glycolysis several hours after TLR stimulation at least in myeloid dendritic cells (35,36). This is in line with our data showing an exaggerated switching from OXPHOS to glycolysis in IL-10-deficient macrophages 12 hours after LPS activation, where the inhibition of mTORC1 activation by IL-10 is impaired. Second, the inhibition of mTORC1 is known to strongly induce autophagy, suggesting a likely mechanism for induction of mitophagy by IL-10. Third, it has also been shown that mTORC1 activation potentiates the expression of IL-10 (37). Our data therefore suggest a negative-feedback loop for the mTORC1 pathway, where production of IL-10 leads to the suppression of mTORC1 activation, resulting in the shutdown of signaling after 6 hours of LPS activation, as seen in control macrophages we observed. It remains to be addressed if IL-10 also controls other metabolic processes associated with macrophage activation via inhibiting the mTOR network.

Among various upstream negative regulators of mTORC1 that have been identified, we demonstrate that the expression of DDIT4 is strongly up-regulated by IL-10 during macrophage activation and that the IL-10-STAT3-DDIT4 axis is important for the inhibition of mTORC1 and the maintenance of overall mitochondrial integrity during macrophage activation by LPS. To inhibit mTOR, DDIT4 interacts with other proteins involved in mTOR signaling, such as 14-3-3 proteins, which regulate the tumor suppressor complex (38), or protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), which dephosphorylates and thus inactivates Akt (39). In line with the latter mechanism, we also find that IL-10 inhibits phosphorylation of Akt target proteins, such as PRAS40 and mTOR. Furthermore, activation of AMPK by IL-10 as shown here and in a previous study (20) is also likely to contribute to the inhibition of mTOR.

In conclusion, our study reveals a key role of IL-10 in controlling cellular metabolism via inhibiting mTORC1. We propose that this metabolic control by IL-10 is critical to control of inflammation. Defects in this regulation (i.e., enhanced or prolonged mTORC1 activation) can result in abnormal metabolic changes (e.g., exaggerated glycolysis) and loss of mitochondrial integrity, as seen in activated macrophages from IL-10- deficient mice with spontaneous colitis or IBD patients with null mutation in IL-10R genes, which have increased inflammatory responses. Note that the aberrant inflammasome activation by mitochondrial ROS due to loss of mitochondrial integrity in macrophages devoid of IL-10 signaling has a significant contribution to severe intestinal inflammation in IBD. Therapeutic targeting of the mTORC1 pathway in macrophages therefore could be beneficial for treatment or prevention of inflammatory diseases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all members of the Medzhitov lab for discussions and D. M. Sabatini for helpful suggestions. We thank R. Flavell (Yale University) for Casp1−/− mice, D. Mizushima for Atg5flox/flox mice (Tokyo Medical and Dental University), H. Virgin (Washington University) for Atg5flox/flox LysM-Cre mice, L. Ellisen (Massachusetts General Hospital) for bone-marrow cells from Ddit4−/− mice, S. Kaech (Yale University) for the use of Seahorse Analyzer, M. Staron and P.-C. Ho for assistance with Seahorse assays, the Yale Stem Cell Center for RNA-seq, Y. Kong for RNA-seq analysis, N. Allen and I. Brodsky for retroviral vector pMSCV-NLRP3/IRES-GFP, and C. Annicelli and S. Cronin for animal care. All data reported in this manuscript are tabulated in the main paper and supplementary materials. This work was supported by Helmsley Charitable Trust, Blavatnik Family Foundation, Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung, and grants from the NIH (R01 AI046688, DK071754, and CA157461 to R.M.). R.M. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Ouyang W, Rutz S, Crellin NK, Valdez PA, Hymowitz SG, Annu. Rev. Immunol 29, 71–109 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shouval DS et al. , Immunity 40, 706–719 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zigmond E et al. , Immunity 40, 720–733 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franke A et al. , Nat. Genet 40, 1319–1323 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franke A et al. , Nat. Genet 42, 1118–1125 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kühn R, Löhler J, Rennick D, Rajewsky K, Müller W, Cell 75, 263–274 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Begue B et al. , Am. J. Gastroenterol 106, 1544–1555 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grütz G, J. Leukoc. Biol 77, 3–15 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeuchi O, Akira S, Cell 140, 805–820 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearce EL, Pearce EJ, Immunity 38, 633–643 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganeshan K, Chawla A, Annu. Rev. Immunol 32, 609–634 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Neill LAJ, Pearce EJ, J. Exp. Med 213, 15–23 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vats D et al. , Cell Metab 4, 13–24 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodríguez-Prados JC et al. , J. Immunol 185, 605–614 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuzumi M, Shinomiya H, Shimizu Y, Ohishi K, Utsumi S, Infect. Immun 64, 108–112 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tal MC et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 2770–2775 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinberg SE, Sena LA, Chandel NS, Immunity 42, 406–417 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizushima N et al. , Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 1101–1111 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laplante M, Sabatini DM, Cell 149, 274–293 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sag D, Carling D, Stout RD, Suttles J, Immunol J. 181, 8633–8641 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brugarolas J et al. , Genes Dev 18, 2893–2904 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chantranupong L et al. , Cell 165, 153–164 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JH et al. , Cell Metab 18, 792–801 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson TR et al. , Cell 137, 873–886 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sancak Y et al. , Mol. Cell 25, 903–915 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellisen LW, Cell Cycle 4, 1500–1502 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saitoh T et al. , Nature 456, 264–268 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoshi N et al. , Nat. Commun 3, 1120 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tannahill GM et al. , Nature 496, 238–242 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buck MD, O’Sullivan D, Pearce EL, J. Exp. Med 212, 1345–1360 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baseler WA et al. , Redox Biol 10, 12–23 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Everts B et al. , Blood 120, 1422–1431 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wegrzyn J et al. , Science 323, 793–797 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sengupta S et al. , Mol. Cell 40, 310–322 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amiel E et al. , J. Immunol 193, 2821–2830 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amiel E et al. , J. Immunol 189, 2151–2158 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohtani M et al. , J. Immunol 188, 4736–4740 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeYoung MP, Horak P, Sofer A, Sgroi D, Ellisen LW, Genes Dev 22, 239–251 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dennis MD, Coleman CS, Berg A, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR, Sci. Signal. 7, ra68 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.