Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The aim of this study is to determine if the pattern of monthly medical expense can be used to identify individuals at risk of dying, thus supporting providers in proactively engaging in advanced care planning discussions.

BACKGROUND

Identifying the right time to discuss end of life can be difficult. Improved predictive capacity has made it possible for nurse leaders to use large data sets to guide clinical decision making.

METHODS

We examined the patterns of monthly medical expense of Medicare beneficiaries with life-limiting illness during the last 24 months of life using analysis of variance, t tests, and stepwise hierarchical linear modeling.

RESULTS

In the final year of life, monthly medical expense increases rapidly for all disease groupings and forms distinct patterns of change.

CONCLUSION

Type of condition can be used to classify decedents into distinctly different cost trajectories. Conditions including chronic disease, system failure, or cancer may be used to identify patients who may benefit from supportive care.

Care at the end of life often involves repeated hospitalizations with the risk of adverse events, unnecessary tests, and failure to follow the individual’s wishes. A recent meta-analysis of 38 studies conducted between 1995 and 2015 found that on average 33% to 38% of patients received nonbeneficial treatment (NBT) in the hospital during their last 6 months of life.1 Not only does NBT contribute to unnecessary suffering, but also it also leads to low-value healthcare utilization.2 In 2014, the Institute of Medicine released recommendations urging physicians and other healthcare providers to discuss end-of-life (EOL) care preferences with patients and their families.3 In 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services approved billing codes to reimburse providers for engaging in these important discussions. Clearly, improving access to appropriate EOL care has become a national priority as the aging population is increasingly living with more chronic diseases.4

Billings and Bernacki5 argue that strategically timing EOL discussions is critically important for the development of relevant advanced care plans (ACPs) that are situated in the context of the patient’s personal wishes and current health state. Identifying the right time to engage in EOL discussions can be difficult. Four major patterns of functional decline in the year leading up to death have been described: sudden death, terminal illness, organ failure, and frailty.6 Similarly, 4 major spending trajectories of Medicare decedents in the last year of life have been identified: high persistent, moderate persistent, progressive, and late rise.7 In an era of population health, we believe it is possible for nurse leaders to use medical expense data to identify patterns of change in spending to discover individuals who are at risk of dying so that timely ACP discussions may be initiated.

Background

Meaningful use of the electronic health record (EHR) has led to an exponential rise in secondary data available to nurse leaders that can be used to develop clinical decision support tools to guide care. Much of this information is available at the provider level in the form of structured health assessment and claims data. Prior research suggests that hospice service use may influence the overall EOL Medicare cost.8–10 Therefore, we examined the patterns of monthly medical expense of Medicare beneficiaries with life-limiting illnesses during the last 24 months of life. The University at Buffalo institutional review board reviewed the proposal for secondary data analysis and determined that the study was not human subject research. We used deidentified Medicare claims data to explore whether the complexity of chronic conditions was associated with decedents’ medical expense trajectories and posed the following 3 questions:

What is the average monthly medical expense of Medicare decedents by hospice election and disease complexity in their final year?

Does electing to use the hospice benefit and chronic condition complexity impact the average medical expenses of the decedents in their final year?

What is the pattern of change of average medical expense during the last 12 months, and how do hospice care and complexity of chronic conditions relate to the pattern of change?

Methods

This study analyzed 2008 data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services contained within a large managed care organization’s database. There were 53 219 beneficiaries; among those, 2335 decedents were identified. Five hundred five beneficiaries were excluded because they died suddenly, and the remaining 1830 decedents were classified into 3 disease categories based on their disease complexity, including “chronic disease,” “system failure and frailty” (system failure), and “cancer.”11 The chronic disease category included chronic lung disease, diabetes, coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis, and other neurology and behavioral health disorders. The system failure category included cirrhosis, multiple sclerosis, kidney failure, heart failure, and cardiopulmonary disease. The cancer disease category included all malignant cancers. Disease complexity is the independent variable in our analysis.

The dependent variable is 30-day mean medical expense (MME) for the 2 years prior to death. We extracted financial data for twenty-four 30-day periods prior to the exact date of death from the health plan’s claims data. Using the date of death to calculate the 30-day periods allowed comparison of expense for number of months prior to death and ensured that the last period was 30 days, rather than a partial month.

Our measure of hospice service access examines if a decedent used hospice services before his/her death. When an individual in the health plan elects to use his/her hospice benefit, he/she is disenrolled from the plan, and payment for care shifts to Medicare fee-for-service; therefore, expenses after transition to hospice care were not available for the analysis. Hospice use was considered as a covariate that was controlled in the analysis when examining the association between the complexity of medical conditions and medical expense trajectory.

Analytic Strategy

We used descriptive statistics to compare MME by disease group and eventual hospice use. We then plotted the overall trajectory of MME during the last 24 months of life and noted that the slope was relatively stable for months 24 through 13, that it increased constantly during the last year of life, and that there were remarkable increases during the last 2 months before death. Therefore, we elected to focus on the final 12 months of life for the analysis. The observed change in the slope of the line at 9 months led to the decision to assign groupings of 9 and 3 months to better understand factors influencing this change.

The analysis examined trends in medical expense for each category and used analysis of variance to compare total medical expense for each of the disease groups for the 1st 9 months of the final year (time 1) and the last 3 months before death (time 2) (Table 1). In addition, independent-sample t test was used to compare cases transferred to hospice care with those who did not use hospice for the 1st 9 months of the final year (time 1) or the last 3 months (time 2) for each of the disease categories. Data were analyzed with Microsoft Excel (Redmond, Washington), HLM 7.0 (Skokie, Illinois), and IBM SPSS 21 (Armonk, New York) statistics.

Table 1.

Mean 30-Day Medical Expenses by Hospice and Disease Groups

| Average MME | Average MME | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Time 1, $ | Time 2, $ | |||

|

|

|

|||

| Complexity Category | n | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Nonhospice user | Cancer | 99 | 4340 ± 4624 | 10 450 ± 7919 |

| System failure | 482 | 2482 ± 2853 | 7384 ± 7141 | |

| Chronic disease | 671 | 1571 ± 2173 | 5927 ± 6606 | |

| Hospice user | Cancer | 144 | 4930 ± 3505 | 5656 ± 5626 |

| System failure | 205 | 2972 ± 3116 | 6191 ± 6552 | |

| Chronic disease | 229 | 1865 ± 2622 | 5382 ± 5713 | |

| Total | Cancer | 243 | 4690 ± 4001 | 7609 ± 7048 |

| System failure | 687 | 2628 ± 2940 | 7028 ± 6987 | |

| Chronic disease | 900 | 1646 ± 2298 | 5788 ± 6391 |

Next, the authors used piecewise hierarchical linear growth modeling, a form of hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) to examine the data. Hierarchical linear modeling provides an integrated approach to study the structure and predictors of individual changes and examines the dynamics of change over time from more than 2 waves of data.12,13 The piecewise approach allowed us to research the nonlinear growth in the individuals using HLM 7.0. The decedent’s MME is positively skewed and was log transformed to achieve a normal distribution. (See Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JONA/A592, and Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JONA/A593, for details of HLM analytical method.)

Results

Trends and Mean Monthly Expense Descriptive Statistics

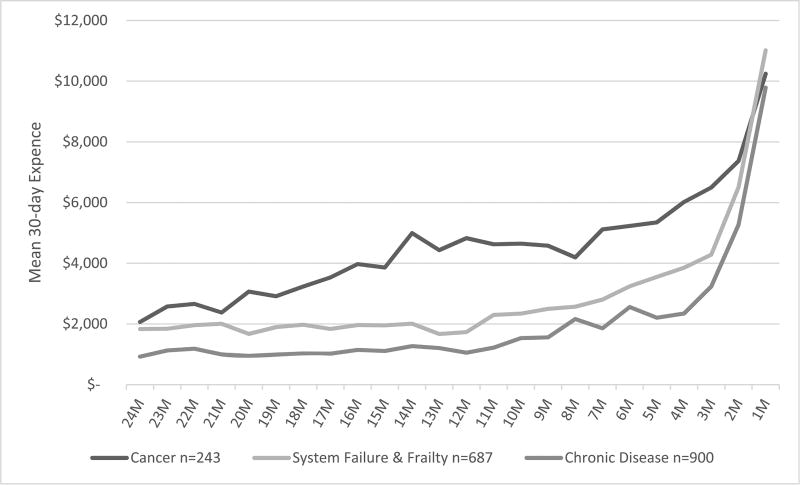

Among the 1830 individual decedents, approximately 49% were classified as chronic disease (n = 900), 38% as system failure and frailty (n = 687), and 13%(n = 243) as cancer. Cost trajectories for 3 complexity groups including chronic disease, system failure and frailty, and malignant cancer were identified. Figure 1 demonstrates trends in average MME for the last 2 years of life by disease complexity. Both chronic disease and system failure show relatively stable monthly expense for the 1st year. The cancer trajectory is higher throughout the 2-year period but shows an increase in the last 6 months. Although costs increase for all categories as death is approached, the trajectories are lowest for chronic disease and highest for “cancer.” In addition, the cancer trajectory increases earlier in the last year.

Figure 1.

Comparison of cancer MME trends last 2 years of life by eventual enrollment in hospice, 2008 (n = 243).

In the final year of life, the MME increases rapidly for all disease groupings; however, the rate of change is more gradual in the 1st 9 months compared with the final 3 months. Table 1 compares the average 30-day expense in months 12 to 4 (time 1) with months 3 to 1 (time 2) and average expense by disease groups and by enrollment in hospice. The SD is often higher than the average 30-day expense because many individuals have months with no medical expense followed by a very expensive month. In general, cancer has the highest MME, followed by system failure, with the lowest expense in the chronic disease grouping in both periods. Persons who elect to use their hospice benefit tend to have higher expense in the prior 9 months than do those who do not elect to use their hospice benefit. However, in the final 3 months, those who enroll in hospice have lower MME.

Impact of Disease Complexity and Hospice Election on End-of-Life Expense

Analysis of variance was used to analyze the differences between the complexity groups. Cancer has significantly higher time 1 expense than either system failure (F = 72.187, P < .001) or chronic disease (F = 234.574, P < .001). Cancer also has significantly higher time 2 (last 3 months) expense than chronic disease (F = 14.865, P < .001), but not system failure (F = 1.237, not statistically significant). Compared with chronic disease, system failure has significantly higher prior time 1 (F = 55.814, P < .001) and time 2 (F = 13.531, P < .001).

Hospice care is designed to avoid futile care at the end of life.14 Figure 2 demonstrates the difference in the 2-year MME trajectory for persons with malignant cancer who elected hospice prior to their death. For cancer patients who elect hospice, this difference is not significant in time 1 (t = 1.129, not statistically significant) using independent-samples t test (Table 2); however, the lower MME for hospice is significant (t = −5.517, P < .001) in the time 2. Furthermore, the MME of those with cancer who do not elect hospice is 1.8 times the MME for hospice users. However, for those with system failure, hospice significantly increased MME in time 1 (t = 2.001, P = .046), but significantly decreased MME in time 2 (t = −2.052, P = .041). Hospice election had no significant impact on MME in those with chronic disease in either period.

Figure 2.

Mean medical expense trajectory for the last 2 years of life by disease for medicare decedents, 2008 (n = 1830).

Table 2.

Independent-Samples t Test Impact of Disease Complexity and Hospice Use on MME

| MME Time 1 | MME Time 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Complexity Category | n | Value, $ | P | Value, $ | P | |

| Cancer | Elected hospice | 99 | 4930 | NS | 5656 | <.001 |

| No hospice | 482 | 4340 | 10 450 | |||

| System failure | Elected hospice | 144 | 2972 | .046 | 6191 | .041 |

| No hospice | 205 | 2482 | 7384 | |||

| Chronic disease | Elected hospice | 243 | 1865 | NS | 5382 | NS |

| No hospice | 687 | 1571 | 5927 | |||

Abbreviation: NS, not statistically significant.

Piecewise HLM

The piecewise HLM analysis focuses on the last 12 months. The average initial monthly expense at the 12th month (T0) prior to death across all decedents was $848. Figure 3 displays the average monthly growth rate from the 12th month to the 3rd month before death (T0 to T9); the corresponding monthly medical expense growth rate was 10.3%, which means the monthly medical expense on average increased 10.3% monthly from the 12th to the 3rd month prior to death (time 1). The average monthly growth rate from the 3rd to the last month of life (T9 to T11, time 2) corresponding monthly medical expense increase was 90.0%, which means medical expense on average increased 90% monthly during the last 3 months of life.

Figure 3.

Trajectory of monthly medical expense for the last year of life for all decedents.

The initial monthly medical expenses (MME T0) for cancer decedents were $2009 (nonhospice) and $2261 (hospice use); for decedents with system failure, these were $1056 (nonhospice) and $1297 (hospice use); for decedents with chronic disease, these were $519 (nonhospice) and $622 (hospice use). Among decedents who did not receive hospice service, the average growth rates during time 2 for decedents with cancer, system failure, and chronic disease were 53.1%, 130.5%, and 165.4%, respectively. Among decedents who received hospice service, the average growth rates during time 2 for decedents with cancer, system failure, and chronic disease were −20.7%, 19.4%, and 34.7%, respectively.

Overall, these results indicated that the monthly growth rates of MME in cancer decedents were the lowest among the 3 disease complexity categories during time 2. The monthly growth rates of MME in almost all decedents during time 2 (19.4% ~ 165.4%), except for cancer decedents with hospice use (−20.7%), were greater than the monthly growth rate (7.6%) in time 1 (9 months prior).

Discussion

A number of conclusions can be drawn from the analysis. First, cost for Medicare decedents increases dramatically at the end of life. Type of condition can be used to classify decedents into distinctly different cost trajectories, chronic disease, system failure, or cancer. When the average monthly expense exceeds $2000 for noncancer diagnoses, the slope of the trajectory increases dramatically. Based on this, it is reasonable to suggest that administrative data can be used to identify cases that may benefit from ACP discussions or referral to supportive care programs focused on keeping the patient out of the hospital.

The average total cost across the population during the end of life cannot reflect whether the medical cost is spent evenly, increases steadily, or grows dramatically at certain time through the last year of life. Piecewise HLM used in this analysis validated our descriptive statistics and provides us with a dynamic picture of medical expense growth at life’s end, addresses the different speeds of medical expense growth during the last year of life, and takes individual’s chronic conditions into consideration.

The initial medical expenses for cancer decedents were the most expensive among the “complexity” groups, which suggests that when cancer treatment is active the medical expense is costly. However, the slow increase or reduction of expense when approaching death may be due to a lack of available cures and transition to providing comfort measures.15 On the other hand, decedents with chronic disease may experience a rapid decline of functional status, which requires more medical care leading to a relatively faster expenditure growth rate.

Limitations

This study is limited by its retrospective feature. Some of the demographic characteristics of individual decedents that were not available in the data set, such as gender and age, may contribute to the unexplained individual variation of medical expense trajectory. The length of hospice service use could not be determined; therefore, the effect of the length of hospice use on the expenditure cannot be examined in this study. The longitudinal design with 30-day data point provides rich information and allows us to examine the trajectory of medical expense as one approaches death. Future research should consider a prospective longitudinal design to collect more information on factors that may have effects on medical expense to examine the growth of medical expense over time. In addition, the effects of hospice use on medical expenditure should only be examined after hospice enrollment, taking the length of hospice use into account.

Implications for Nurse Leaders

Strategically timing EOL conversations has the potential to dramatically affect the quality of ACP efforts; yet, there is a growing body of evidence indicating that in the absence of a clear prognosis providers often hesitate to raise the issue of planning for the final phase of life.3,5,16 Clinically, a dramatic increase in medical expense followed by steady increases for a few months could signal that it is the right time to discuss the patient’s goals and wishes for their remaining days by lending a certain degree of prognostic certainty.17 Armed with this knowledge at the organizational level, nurse leaders will have the evidence base needed to support the implementation of systematic processes, such as the creation of decision support tools or alerts in the EHR, which can be used to identify early decline in people with chronic medical conditions. Thus, nurses at the bedside would be better equipped to engage at-risk individuals and promote ACP activities. Nurse leaders may also want to explore the offering of financial support and counseling for patients at the end of life. Social workers and others may be able to contribute to these programs to help patients and their families anticipate and mitigate the financial impact as their conditions decline.

Conclusion

This study found that 3 months prior to death was a critical time, and a marked increase in expense may be an indicator of impending death, but that costs in the prior year may not be useful for differentiating those at risk of decline. The medical expense for cancer decedents was more costly than those for the other chronic conditions at 1 year prior to death, exhibited a similar rate of increase as other conditions during the 12th to the 3rd month prior to death, but increased slower or even decreased during the last 2 months of life when compared with other chronic conditions. Early identification of high-risk cases would allow for increased patient engagement by nurses to assist in making EOL wishes known to providers and family surrogates and for the development of an ACP. Moreover, this study demonstrates that nurse leaders should consider exploring the data available to them at the organizational level to discover opportunities for conducting provider-level inquiries using pragmatic approaches to data analysis to improve bedside care and associated support systems.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jonajournal.com).

Contributor Information

Ms Suzanne S. Sullivan, School of Nursing, University at Buffalo, State University of New York.

Dr Junxin Li, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Dr Yow-Wu Bill Wu, School of Nursing, University at Buffalo, State University of New York.

Dr Sharon Hewner, School of Nursing, University at Buffalo, State University of New York.

References

- 1.Cardona-Morrell M, Kim J, Turner RM, Anstey M, Mitchell IA, Hillman K. Non-beneficial treatments in hospital at the end of life: a systematic review on extent of the problem. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28:456–469. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzw060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The State of Aging and Health in America. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Billings JA, Bernacki R. Strategic targeting of advance care planning interventions: the Goldilocks phenomenon. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):620–624. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, Lipson S, Guralnik JM. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2387–2392. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis MA, Nallamothu BK, Banerjee M, Bynum JP. Identification of four unique spending patterns among older adults in the last year of life challenges standard assumptions. Health Aff. 2016;35(7):1316–1323. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuckerman RB, Stearns SC, Sheingold SH. Hospice use, hospitalization, and Medicare spending at the end of life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016;71(3):569–580. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, Dominici F, Block S, Cutler DM. Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1888–1896. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley AS, Deb P, Du Q, Aldridge Carlson MD, Morrison RS. Hospice enrollment saves money for Medicare and improves care quality across a number of different lengths-of-stay. Health Aff. 2013;32(3):552–561. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewner S. A population-based care transition model for chronically ill elders. Nurs Econ. 2014;32(3):109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou CP, Yang D, Pentz MA, Hser Y-I. Piecewise growth curve modeling approach for longitudinal prevention study. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2004;46(2):213–225. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) NHPCO’s Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America. Alexandria, VA: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; 2015. [Accessed September 21, 2017]. pp. 1–17. http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2015_Facts_Figures.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith TJ, Hillner BE. Bending the cost curve in cancer care. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):2060–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1013826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lund S, Richardson A, May C. Barriers to advance care planning at the end of life: an explanatory systematic review of implementation studies. Public Libr Sci. 2015;10(2):11–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fowler NR, Hansen AS, Barnato AE, Garand L. Association between anticipatory grief and problem solving among family caregivers of persons with cognitive impairment. J Aging Health. 2013;25(3):493–509. doi: 10.1177/0898264313477133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.