Abstract

Background

It is difficult to decide whether to inform the child of the incurable illness. We investigated attitudes of the general population and physicians toward prognosis disclosure to children and associated factors in Korea.

Methods

Physicians working in one of 13 university hospitals or the National Cancer Center and members of the general public responded to the questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of the age appropriate for informing children about the prognosis and the reason why children should not be informed. This survey was conducted as part of research to identify perceptions of physicians and general public on the end-of-life care in Korea.

Results

A total of 928 physicians and 1,241 members of the general public in Korea completed the questionnaire. Whereas 92.7% of physicians said that children should be informed of their incurable illness, only 50.7% of the general population agreed. Physicians were also more likely to think that younger children should know about their poor prognosis compared with the general population. Physicians who opposed incurable illness disclosure suggested that children might not understand the situation, whereas the general public was primarily concerned that disclosure would exacerbate the disease. Physicians who were women or religious were more likely to want to inform children of their poor prognosis. In the general population, gender, education, comorbidity, and caregiver experience were related to attitude toward poor prognosis disclosure to children.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that physicians and the general public in Korea differ in their perceptions about informing children of poor prognosis.

Keywords: Pediatric Palliative Care, Prognostic Disclosure to Children, Pediatric Advance Care Planning, Republic of Korea

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

When a child is diagnosed with incurable illness, both physicians and parents face the difficult question of whether they should talk about prognosis with the child. Although honest discussions may help caregivers provide better support, they are concerned about how this distressing information might negatively affect the child. In the adult setting, extensive research shows that patients benefit from prognostic communication.1,2,3,4 Patients who know the outcome of their illness and its treatment options are able to make appropriate decisions regarding care.4,5 Similarly, adults who have unrealistic expectations about the length of their remaining life tend to choose more aggressive care, which can result in poor quality of life at the end of life.3 Furthermore, several studies show that prognostic communication and planning of end-of-life care does not cause psychological harm to patients or families.4,6 Some studies suggest that aggressive care, such as continued chemotherapy and life-sustaining treatments, and prolonged hospitalization in the last month of life are coupled with a lack of hospice care.7,8

Evidence suggests that not only adults but also children with serious illness benefit from open communication about prognosis, and several clinical guidelines have been published.9,10,11,12 Because decision-making in the pediatric setting relies on a triangular relationship involving the physician, parent, and child,13 more thoughtful attention is required in communication. Also, it has previously been observed that the older the child is, the more often parents talk to their child about death and they regret about not having talked about it.10

Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, few studies have explored people's attitudes toward disclosure of incurable state to children according to their age. Therefore, this study was designed to examine attitudes toward poor prognosis disclosure to children and associated factors in the general population and physicians in Korea. The results increase our understanding of concordance of perceptions toward poor prognosis disclosure to children in two different groups and help further discussions about end-of-life care.

METHODS

Participants and procedures

Thirteen university hospitals and the National Cancer Center in Korea were involved in the study. For physicians, we distributed invitations to participate via email through 14 hospitals and the Korean Medical Association. Each invitation packet included an application form and instructions for participating in the study. For the general population, we sampled 1,241 locally distributed respondents who were 20–70 years of age using the probability-proportional-to-size technique14 and administered the structured questionnaire.

Questionnaire

This survey was conducted as part of research to identify perceptions of physicians and general public on the end-of-life care in Korea. We constructed a questionnaire examining attitudes toward disclosure of the incurable diagnosis to pediatric patients based on a literature review and discussion of research team including pediatricians and palliative care physicians. The questionnaire posed the question, “If a pediatric patient is diagnosed with incurable illness, do you think the patient should be informed?” and included five answer choices: 1) yes, if the patient is older than 4 years old; 2) yes, if the patient is older than 7 years old; 3) yes, if the patient is older than 12 years old; 4) yes, if the patient is older than 15 years old; or 5) no disclosure. When a respondent answered “no disclosure,” they were asked to choose from the following reasons: 1) disclosure can deteriorate illness by causing emotional distress, 2) children cannot recognize the situation correctly, 3) disclosure causes patients to lose hope and discourages them from fighting the disease, 4) disclosure of incurable illness to children is not the right thing to do, 5) the prognosis may not be accurate, or 6) disclosure is not necessary because important decisions are made by the family rather than the children. The questionnaire also collected demographic and other information including age, gender, level of education, job status, income, religion, comorbidity, and caregiving experience.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed differences in attitudes toward disclosing incurable diagnosis to pediatric patients between the general population and physicians. To eliminate potential selection bias from background covariates within the physician group, we applied a propensity score adjustment and weighting method. These methods created an adjusted physician population having characteristics of the original reference general population. Correlations between attitude toward incurable illness disclosure and demographic and other variables were assessed by univariate analysis. We used χ2 tests to determine significant differences in variables between respondents who are in favor of or in opposition to poor prognosis disclosure to children. In addition, for factors with significant associations in univariate analyses, we performed multiple regression analyses to identify which independent variables best predicted attitudes toward the disclosure of serious illness to children. Odds ratios (ORs) greater than 1 represent a greater likelihood of believing that pediatric patients should know about their prognosis. For these analyses, we set the significance level at P < 0.05. We used SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to perform statistical analyses.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of each hospital (Seoul National University Hospital IRB No. E-1612-102-815). Informed consent was submitted by all subjects when they were enrolled. We conducted the study in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

A total of 1,241 members of the general population and 928 physicians in Korea completed the questionnaire. The physician group was composed of more men than women and was significantly younger than the general population. There were also more people who were religious (58.4% vs. 41.4%), had a comorbidity (6.3% vs. 2.7%), and had caregiver experience (51.2% vs. 22.7%) in the physician group than in the general population. However, these demographic differences did not remain significant after adjustment using the propensity score weighting method (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the general population and physicians before and after propensity score adjustment.

| Category | General population (n = 1,241) | Physicians (n = 928) | Wald Fa | P value | General populationb | Physiciansc | Wald Fa adjusted for propensity scored | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 28.632 | < 0.001 | 2.149 | 0.143 | |||||

| Men | 612 (49.3) | 565 (60.9) | 53.9 | 56.1 | |||||

| Women | 629 (50.7) | 363 (39.1) | 46.1 | 43.9 | |||||

| Age, yr | 177.180 | < 0.001 | 0.334 | 0.563 | |||||

| < 40 | 460 (37.1) | 612 (65.9) | 49.5 | 50.3 | |||||

| ≥ 40 | 781 (62.9) | 316 (34.1) | 50.5 | 49.7 | |||||

| Education (not stated, n = 4) | 731.048 | < 0.001 | - | - | - | - | |||

| Did not complete college | 672 (54.3) | 0 (0) | |||||||

| Completed college | 565 (45.7) | 928 (100) | |||||||

| Job status (not stated, n = 95) | 390.180 | < 0.001 | - | - | - | - | |||

| No | 391 (34.1) | 0 (0) | |||||||

| Yes | 755 (65.9) | 928 (100) | |||||||

| Monthly income, 1,000 KRW | 738.631 | < 0.001 | - | - | - | - | |||

| < 4,000 | 673 (54.8) | 0 (0) | |||||||

| ≥ 4,000 | 556 (45.2) | 928 (100) | |||||||

| Religion | 61.327 | < 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.907 | |||||

| No | 727 (58.6) | 386 (41.6) | 51.8 | 52.0 | |||||

| Yes | 514 (41.4) | 542 (58.4) | 48.2 | 48.0 | |||||

| Comorbidity | 16.108 | < 0.001 | 0.689 | 0.407 | |||||

| No | 1,207 (97.3) | 870 (93.8) | 96.2 | 95.7 | |||||

| Yes | 34 (2.7) | 58 (6.3) | 3.8 | 4.3 | |||||

| Caregiver experience | 189.309 | < 0.001 | 0.095 | 0.757 | |||||

| No | 959 (77.3) | 453 (48.8) | 65.0 | 64.6 | |||||

| Yes | 282 (22.7) | 475 (51.2) | 35.0 | 35.4 | |||||

| Experience caring for a seriously ill patient in last 1 year | - | - | - | - | |||||

| No | - | 525 (56.6) | - | 57.4 | |||||

| Yes | - | 403 (43.4) | - | 42.6 | |||||

Values are presented as number (%).

aF statistics based on Wald χ2 test statistics; bGeneral population sample size, n = 1,241; weighted, n = 2,166.47; cPhysician sample size, n = 928; weighted, n = 2,148.38; dPropensity score was calculated by differences in gender, age, religion, comorbidity, and caregiving experience.

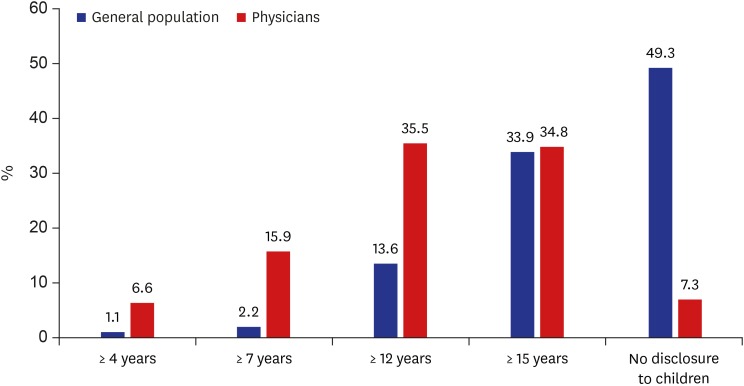

Attitude toward disclosing incurable illness to children according to patient's age

We observed significant discordance between the general population and physicians in their attitude toward disclosure of incurable status to children (P < 0.001; Fig. 1). Among physicians, only 7.3% of respondents said they do not want children to be informed of the serious illness, whereas 49.3% of the general population were opposed to this disclosure. Among those who responded that children should be informed of their illness prognosis, physicians tended to be more likely than the general population to think that younger children should know about their serious condition. The reasons that respondents gave for answering “no” to the question of disclosure are given in Table 2. Whereas physicians who did not want to disclose poor prognosis to children chose children's ignorance as the main reason, members of the general population who said “no” to disclosure were concerned that disclosure could worsen the illness by causing emotional distress.

Fig. 1. Proportion of general population and physicians who agreed with disclosing incurable illness to pediatric patients according to the child's age.

Table 2. Why did you answer “no” regarding disclosure of an incurable illness to pediatric patients?

| Reasons | General population (n = 1,067.94) | Physicians (n = 155.97) |

|---|---|---|

| Disclosure can deteriorate illness by causing emotional distress. | 407 (38.1) | 20 (13.0) |

| Children cannot recognize the situation correctly. | 287 (26.9) | 69 (44.8) |

| Disclosure causes patients to lose hope and discourages them from fighting the disease. | 182 (17.0) | 35 (22.7) |

| Disclosure of terminal illness to children is not the right thing to do. | 51 (4.8) | 30 (19.5) |

| The prognosis may not be accurate. | 72 (6.7) | 0 (0) |

| Disclosure is not necessary because important decisions are made by the family rather than the children. | 69 (6.5) | 0 (0) |

Values are presented as number (%).

Univariate logistic regression analyses of factors related to disclosure to children

After adjustment using the propensity score weighting method, we analyzed factors related to wanting disclosure to children in each group with univariate logistic regression (Table 3). Among the general population, respondents who were men or had higher education status, existing comorbidity, or caregiver experience were more likely to want to disclose serious illness to children. On the other hand, physicians who were women, younger, or religious were more likely to think that children should be informed of their impending death.

Table 3. Univariate analysis for disclosing incurable illness to pediatric patientsa .

| Category | General population | Physicians | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No disclosure | Disclosure | P value | No disclosure | Disclosure | P value | ||

| Gender | 0.002 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Men | 540 (46.2) | 628 (53.8) | 118 (9.8) | 1,087 (90.2) | |||

| Women | 528 (52.9) | 471 (47.1) | 38 (4.0) | 905 (96.0) | |||

| Age, yr | 0.352 | 0.010 | |||||

| < 40 | 517 (48.3) | 554 (51.7) | 63 (5.8) | 1,019 (94.2) | |||

| ≥ 40 | 550 (50.3) | 544 (49.7) | 93 (8.7) | 974 (91.3) | |||

| Education (not stated, n = 4) | 0.003 | - | |||||

| Did not complete college | 548 (52.8) | 490 (47.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Completed college | 519 (46.3) | 601 (53.7) | 156 (7.3) | 1,992 (92.7) | |||

| Job status (not stated, n = 95) | 0.215 | - | |||||

| No | 309 (52.0) | 285 (48.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Yes | 669 (49.0) | 697 (51.0) | 156 (7.3) | 1,992 (92.7) | |||

| Monthly income, 1,000 KRW | 0.273 | - | |||||

| < 4,000 | 573 (50.4) | 564 (49.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| ≥ 4,000 | 487 (48.0) | 527 (52.0 | 156 (7.3) | 1,992 (92.7) | |||

| Religion | 0.106 | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 572 (51.0) | 550 (49.0) | 103 (9.2) | 1,014 (90.8) | |||

| Yes | 496 (47.5) | 548 (52.5) | 53 (5.1) | 979 (94.9) | |||

| Comorbidity | 0.002 | 0.136 | |||||

| No | 1,041 (50.0) | 1,043 (50.0) | 153 (7.4) | 1,904 (92.6) | |||

| Yes | 27 (32.9) | 55 (67.1) | 3 (3.3) | 88 (96.7) | |||

| Caregiver experience | < 0.001 | 0.826 | |||||

| No | 774 (54.9) | 635 (45.1) | 102 (7.4) | 1,285 (92.6) | |||

| Yes | 297 (38.8) | 463 (61.2) | 54 (7.1) | 707 (92.9) | |||

| Experience caring for a seriously ill patient in last 1 year | - | 0.351 | |||||

| No | - | - | 84 (6.8) | 1,149 (93.2) | |||

| Yes | - | - | 72 (7.9) | 843 (92.1) | |||

Values are presented as number (%).

aWeighted with propensity score calculated by differences in gender, age, religion, comorbidity, and caring experience between the general population and physicians.

Multiple logistic regression analyses of factors related to disclosure to children

For factors with significant associations in univariate analysis within each group, we performed stepwise multiple regression analyses for attitude toward disclosure (Table 4). In the general population analysis, respondents who were men (adjusted OR [aOR], 1.277; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.072–1.522) or had a higher level of education (aOR, 1.314; 95% CI, 1.102–1.566), comorbidity (aOR, 1.894; 95% CI, 1.171–3.066), or caregiver experience (aOR, 1.915; 95% CI, 1.595–2.298) were more likely to think children with incurable illness should be told about their health status. In the physician analysis, respondents who were women (aOR, 2.562; 95% CI, 1.756–3.737) or religious (aOR, 1.843; 95% CI, 1.305–2.603) were more likely to want to inform children about their poor prognosis.

Table 4. Multivariate analysis for disclosing incurable illness to pediatric patientsa.

| Category | General population | Physicians | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Gender | 0.006 | < 0.001 | |||

| Men | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Women | 0.783 (0.657–0.933) | 2.562 (1.756–3.737) | |||

| Age, yr | - | NS | - | ||

| < 40 | - | ||||

| ≥ 40 | - | ||||

| Education (not stated, n = 4) | 0.002 | - | |||

| Did not complete college | 1 [Reference] | - | |||

| Completed college | 1.314 (1.102–1.566) | - | |||

| Job status (not stated, n = 95) | - | - | |||

| No | - | - | |||

| Yes | - | - | |||

| Monthly income, 1,000 KRW | - | - | |||

| < 4,000 | - | - | |||

| ≥ 4,000 | - | - | |||

| Religion | - | 0.001 | |||

| No | - | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Yes | - | 1.843 (1.305–2.603) | |||

| Comorbidity | 0.009 | - | |||

| No | 1 [Reference] | - | |||

| Yes | 1.894 (1.171–3.066) | - | |||

| Caregiver experience | < 0.001 | - | |||

| No | 1 [Reference] | - | |||

| Yes | 1.915 (1.595–2.298) | - | |||

| Experience caring for a seriously ill patient in last 1 yr | - | - | |||

| No | - | - | |||

| Yes | - | - | |||

aOR = adjusted odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, NS = not significant.

aWeighted with propensity score calculated by differences in gender, age, religion, comorbidity, and caring experience between the general population and physicians.

DISCUSSION

We found significant discordance between members of the general population and physicians in their views about disclosure of incurable illness to patients under 18 years old. The two groups also differed in their attitude about the appropriate age of children to be informed of their prognosis. One of the biggest concerns for physicians and parents in advance care planning is whether to tell the child the truth. In this respect, the fact of the significant divergence between the two groups' opinions has considerable implications even considering the general population is not the same group as the parents.

Recently, investigators reviewed trends in the literature on prognostic disclosure to children.15 Unlike before the 1960s,16,17,18 when most physicians thought that children should not be informed of their illness because of the potential inaccuracy of prognosis and the possibility of harmful effects on children, a growing body of evidence and clinical guidelines since the 1970s continued to facilitate movement toward open communication with children. In our study, 92.8% of physicians answered that they want children to know about their incurable illness. This result is surprising given the current medical situation in which half of patients are not informed of their prognosis.19 Physicians report reluctance to undertake advance care planning for pediatric patients due to several barriers such as not knowing the right thing to say, unrealistic expectations of parents, and prognostic uncertainty.20,21 Due to these barriers, there may be a gap in physicians' perception and actual practice of prognosis disclosure.

Because children are neither legally nor developmentally equivalent to autonomous adults, treatment decision or truth-telling for children should be made with respect to their family context.22 Families frequently do not let patients know bad news to give them hope for the future and encourage them to fight the disease.23,24 In the situation in which the patient is a child, the idea of protecting the patient by not informing them of their incurable state may be stronger.9,25 In our study, members of the general population identified concerns about disease worsening due to emotional distress as the most important reason for not telling the truth to children. This is consistent with previous studies indicating that parents often try to protect their children by withholding poor prognostic information in their role as caregivers.25,26 However, it is conceivable that children are already aware of the poor prognosis even if they do not show their awareness, and this mutual pretense could be harmful to children who may experience emotional isolation.10,27 Furthermore, according to one cohort study of bereaved parents, no parent regretted having talked with his or her child about death.10

We found differences in attitude between the general public and physicians about the age of children who should know their prognosis. Although children vary in their capacity for involvement in treatment decision-making according to their level of maturity or illness experience, a developmentally typical child older than 7 is usually considered capable of assenting to a surrogate's decision.22 In our study, only 16.9% of the general public said that pediatric patients should be informed of their poor prognosis if they are over 12 years old, whereas 58.0% of physicians agreed with this statement. In contrast to the attitude of the general public in our study, a previous study of bereaved parents' end-of-life care experiences found that no one regretted having talked about death with their child, while some of the parents who did not talk were regretful.10 It may be interpreted as the difference of the perspectives between the parents and the general public due to the lack of experience and knowledge of the care of the child with serious illness, but it may be because of a cultural difference. Although there are not many studies, it is usually the parent's role to decide on the child without notifying the child of the serious situation in Asia or Middle Eastern countries, and the tendency to think that it is moral to continue aggressive treatment till the end-of-life is known to be stronger than the western countries.28 It will be necessary to study the perspectives of pediatric patients and parents on prognostic disclosure in Asia including Korea.

Higher education, having comorbidity, and caregiver experiences were found to be independently associated with agreement with prognostic disclosure to children with serious illnesses in general public group. This result is consistent with previous study which showed that patients with a higher level of education had favorable attitudes toward the necessities of advance directives.29 Respondents with comorbidity or caregiver experiences might have had a chance to think about the necessities of talking about health status with loved ones.

It is very distressing to determine whether to inform a child who is dying. Despite the dazzling development of modern medicine, over 1,000 children with complex chronic conditions die in Korea every year.30 The large perception discrepancy between physicians and non-physicians suggests that conflict may arise in communication about end-of-life care for children. Clinicians should be trained to identify families' worries and facilitate open communication while respecting that every family has unique needs. Furthermore, although an individualized approach is emphasized in the advance care planning of children, it seems necessary to develop communication guidelines and education according to the child's age.

Our study has some limitations. First, we surveyed physicians regardless of their specialty, so the results may not fully reflect pediatricians' views. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to identify a gap in preference toward incurable illness disclosure to children between physicians and the general public. Second, although we compared our results with those of studies conducted in other countries, our study included Koreans only, therefore our findings should be interpreted against the background of cultural factors. Finally, we did not assess pediatric patients' or parental perspectives regarding serious illness disclosure. Because previous study showed 96.1% of Korean adult cancer patients wanted to be informed if their illness is terminal, pediatric patients or parents could have different views about prognostic disclosure from general population.24 Further studies are needed to more fully characterize the attitudes and barriers toward communication with children about death and dying.

In conclusion, our study suggests that Korean physicians and the general public have different opinions regarding serious illness disclosure to children. Further research is needed to determine how to improve end-of-life communication in the physician-parent-child relationship.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to the staff from World Research Inc. in Korea for interviewing the general population. We also thank to Dr. Young Joo Lee and Dr. Hyun-Jeong Shim who cooperated in conducting the survey.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (No. HC15C1391) and partially by the Seokchun Daewoong Foundation (No. 80020160249).

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Kim MS, Park JD, Yun YH.

- Data curation: Lee J.1

- Formal analysis: Lee J,1 Sim JA.

- Investigation: Kwon JH, Kang EJ, Kim YJ, Lee J,2 Song EK, Kang JH, Nam EM, Kim SY, Yun HJ, Jung KH.

- Methodology: Sim JA.

- Resources: Kwon JH, Kang EJ, Kim YJ, Lee J,2 Song EK, Kang JH, Nam EM, Kim SY, Yun HJ, Jung KH.

- Writing - original draft: Kim MS.

- Writing - review & editing: Kim MS, Yun YH.

Lee J,1 Jihye Lee; Lee J,2 Junglim Lee.

References

- 1.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O'Day SJ, Peterson LM, Wenger N, Reding D, et al. Relationship between cancer patients' predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279(21):1709–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(14):1061–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy DJ, Burrows D, Santilli S, Kemp AW, Tenner S, Kreling B, et al. The influence of the probability of survival on patients' preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(8):545–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402243300807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Mitchell SL, El-Jawahri A, Davis AD, Barry MJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a video decision support tool for cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision making in advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(3):380–386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.9570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marron JM, Cronin AM, Kang TI, Mack JW. Intended and unintended consequences: ethics, communication, and prognostic disclosure in pediatric oncology. Cancer. 2018;124(6):1232–1241. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tzuh Tang S, Hung YN, Liu TW, Lin DT, Chen YC, Wu SC, et al. Pediatric end-of-life care for Taiwanese children who died as a result of cancer from 2001 through 2006. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(7):890–894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JD, Kang HJ, Kim YA, Jo M, Lee ES, Shin HY, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life care for Korean pediatric cancer patients who died in 2007–2010. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claflin CJ, Barbarin OA. Does “telling” less protect more? Relationships among age, information disclosure, and what children with cancer see and feel. J Pediatr Psychol. 1991;16(2):169–191. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/16.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, Onelöv E, Henter JI, Steineck G. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(12):1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vernick J, Karon M. Who's afraid of death on a leukemia ward? Am J Dis Child. 1965;109(5):393–397. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1965.02090020395003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(33):5265–5270. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mack JW, Joffe S. Communicating about prognosis: ethical responsibilities of pediatricians and parents. Pediatrics. 2014;133(Suppl 1):S24–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3608E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy PS, Lemeshow S. Sampling of Populations: Methods and Applications. 5th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sisk BA, Bluebond-Langner M, Wiener L, Mack J, Wolfe J. Prognostic disclosures to children: a historical perspective. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161278. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagy M. The child's theories concerning death. J Genet Psychol. 1948;73(First Half):3–27. doi: 10.1080/08856559.1948.10533458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Death in childhood. Can Med Assoc J. 1968;98(20):967–969. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvarez WC. Care of the dying. J Am Med Assoc. 1952;150(2):86–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.1952.03680020020006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yun YH, Kwon YC, Lee MK, Lee WJ, Jung KH, Do YR, et al. Experiences and attitudes of patients with terminal cancer and their family caregivers toward the disclosure of terminal illness. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1950–1957. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.9658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forbes T, Goeman E, Stark Z, Hynson J, Forrester M. Discussing withdrawing and withholding of life-sustaining medical treatment in a tertiary paediatric hospital: a survey of clinician attitudes and practices. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008;44(7-8):392–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2008.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies B, Sehring SA, Partridge JC, Cooper BA, Hughes A, Philp JC, et al. Barriers to palliative care for children: perceptions of pediatric health care providers. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):282–288. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berlinger N, Jennings B, Wolf SM. The Hastings Center Guidelines for Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment and Care Near the End of Life. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Surbone A. Truth telling to the patient. JAMA. 1992;268(13):1661–1662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yun YH, Lee CG, Kim SY, Lee SW, Heo DS, Kim JS, et al. The attitudes of cancer patients and their families toward the disclosure of terminal illness. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(2):307–314. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Badarau DO, Wangmo T, Ruhe KM, Miron I, Colita A, Dragomir M, et al. Parents' challenges and physicians' tasks in disclosing cancer to children. A qualitative interview study and reflections on professional duties in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(12):2177–2182. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bluebond-Langner M, Belasco JB, DeMesquita Wander M. “I want to live, until I don't want to live anymore”: involving children with life-threatening and life-shortening illnesses in decision making about care and treatment. Nurs Clin North Am. 2010;45(3):329–343. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hilden JM, Watterson J, Chrastek J. Tell the children. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(17):3193–3195. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg AR, Starks H, Unguru Y, Feudtner C, Diekema D. Truth telling in the setting of cultural differences and incurable pediatric illness: a review. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1113–1119. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keam B, Yun YH, Heo DS, Park BW, Cho CH, Kim S, et al. The attitudes of Korean cancer patients, family caregivers, oncologists, and members of the general public toward advance directives. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(5):1437–1444. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1689-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim MS, Lim NG, Kim HJ, Kim C, Lee JY. Pediatric deaths attributed to complex chronic conditions over 10 years in Korea: evidence for the need to provide pediatric palliative care. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(1):e1. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]