Abstract

Background:

Satisfaction with life is recognized to be a factor in alleviating burden in stressful caregiving duties. However, the mechanism underlying this relationship is indistinct. Positive aspects of caregiving (PAC) may help to regulate caregiving burden among caregivers of older adults. The study aims to examine whether positive caregiving characteristics mediate the effect between satisfaction with life and burden of care.

Methods:

Participants were 285 caregivers of older adults (aged 60 and above) in Singapore and were recruited in a cross-sectional, self-report study (mean [M] = 47.0 years; 64.6% females). Measures included in the study were the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI), Positive Aspects of Caregiving (PAC), and the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS). Mediation analyses were used to study the indirect effects of life satisfaction on caregiver burden through features of PAC.

Results:

Mean scores for the ZBI, PAC, and SWLS scales were M = 23.15 (standard deviation [SD] = 15.98), M = 34.55 (SD = 8.19), and M = 23.56 (SD = 6.62) respectively. Results from the mediation analysis revealed that the association between life satisfaction and caregiving burden was significantly mediated by the PAC (P < .001).

Discussion:

Positive aspects of caregiving may be a mechanism that links satisfaction with life and caregiver burden. Findings may represent attempts to manage caregiving duties as well as maintaining a positive attitude toward their responsibilities.

Keywords: caregiving, caregiver, burden, satisfaction with life, positive caregiving, older adults

Introduction

Improvements in global health have increased both population growth and longevity. In 2013, life expectancy rose to 71.5 years, increasing from 65.3 in 1990.1 The World Health Organization2 predicts that the number of people aged above 60 will increase by 10% and reach 2 billion by 2050. Along with these growing numbers of older adults, support activities of daily living is also forecast to quadruple and many may require continual care. The cost of care for older adults is undeniable and will continue to rise along with the rapidly aging population. Caregivers in the United States providing health-related services are valued at an estimated US$350 billion in 20063 underscoring their critical role in long-term care. In Singapore, the cost of dementia care in 2013 was estimated at S$532 million with an annual cost of over S$10 000 per patient a year.4

The role of caregiving is often taken up by family members of the recipient, making them an integral national health-care resource for individuals with a myriad of conditions like dementia, age-related chronic conditions, and cancer. Informal caregivers are usually described as persons closely involved in offering care to older adults without monetary return.5 Assuming the role of an informal caregiver can be extremely demanding and is often perceived as a chronic stressor. A meta-analysis of the physical and psychological health involving caregivers and noncaregivers found large differences in stress, depression, self-efficacy, and individual well-being between the 2 groups.6 Caregivers experience perceived burden, which is the negative psychological, behavioral, and physiological effects on their lives and health.7

Satisfaction With Life and Positive Aspects of Caregiving

Past research has shed light on the risk factors of caregiver burden, such as female sex, lower education, living with the care recipient, financial difficulties, and lack of choice in assuming the role of caregiver.8 In addition, studies have observed that the amount of care provided and the unmet demands for psychosocial care and assistance in daily living activities were also associated with higher burden of care.9,10 Studies8,11 have traditionally documented that life satisfaction is largely influenced by the degree of burden perceived by the caregiver; caregivers with low degree of burden experience high satisfaction, while those with high degree of burden experience low satisfaction. On the contrary, studies have also found that low life satisfaction was significantly associated with high perceived burden,12,13 indicating a reverse relationship between life satisfaction and burden.

Caregivers also experience positive consequences throughout the caregiving process.14–17 Perceived gain or reward, satisfaction, or an increase in self-esteem are some of the positive effects of the caregiving relationship. A survey conducted in the United States by the National Opinion Research Center18 found that 83% of caregivers rated their caregiving experience positively and it helped strengthen their relationship with the care recipient despite being a cause of stress in the household. Lawton and colleagues19 propose a 2-factor model where emotional distress, psychological satisfaction, and growth occur simultaneously in the caregiving experience. An ability to find meaning through positive appraisals and spiritual or religious belief acts as coping mechanism in stressful situations, where caregivers feel a sense of pride and purpose in their roles. A cross-sectional study conducted among Asian family caregivers of patients with dementia in Singapore revealed that a significant predictor of gain was the use of encouragement. Spirituality and religion predicted gain indirectly via the use of encouragement.20 Thus, the caregiving experience has positive aspects that are satisfying and rewarding and may improve the caregiver’s psychological well-being by serving as a buffer against negative consequences.13

There is evidence21–23 to suggest that positive associations with the caregiving role may be a mediation mechanism that links life satisfaction with self-perceived burden of care. Higher life satisfaction has been documented to be significantly associated with a more positive outlook on caregiving.24 Caregivers tend to report higher life satisfaction even in the presence of increased burden of care contributed by positive caregiving experience.25 This could be due to the caregiver’s role perceived as pivotal when the care recipient has increased dependence.

The present study aims to examine the pathway of positive aspects of caregiving (PAC) in informal caregivers of older adults in Singapore. We propose that a positive outlook on the caregiving role mediates the association between satisfaction with life and burden.

Methods

Sample

The study utilized self-report data from a single-phase, cross-sectional analysis conducted with informal caregivers of older adults in Singapore. Participants included in the study were Singaporeans or permanent residents between the ages of 21 and 65 years old, were fluent and understood English, and were current informal caregivers of at least 1 older adult aged 60 years and above. The study excluded those who were non-English-speaking and whose care recipients were long-term residents in hospice or nursing homes. The study and all the relevant materials used were approved by the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board. Trained members of the study team explained the procedures involved in the study to participants prior to obtaining their consent.

Recruitment

Participants were informal caregivers of elderly adults previously recruited in the Well-being of Singapore Elderly (WiSE) study who were agreeable to be recontacted for future studies26 as well as those of elderly patients from Singapore’s main psychiatric hospital, the Institute of Mental Health (IMH). Following contact via phone or e-mail, arrangements were made for a time and venue for the study to be conducted.

Data Collection

Following the consent procedure, participants completed a series of questionnaires which included sociodemographic details (age, gender, ethnicity, education level, marital and employment status, and relationship to care recipient), care needs of the care recipient, and 3 survey instruments, namely, the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI), PAC, and the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS).

Measures

Zarit Burden Interview

The ZBI is a self-reported, 22-item inventory that measures subjective burden among caregivers and examines the burden associated with functional or behavioral impairments.27 Items on the scale are scored on a 5-point Likert scale which range from never (0) to nearly always (4). Total scores range from 0 to 88, with higher scores indicating greater burden. Bachner and O’Rourke28 discussed that reported reliability coefficients range from α = .83 to α = .94, and concurrent validity with a single global rating of burden is 0.71. Zarit Burden Interview in the current study has a Cronbach α of .926.

Positive Aspects of Caregiving

The PAC is a 9-item instrument that presents statements about the caregiver’s mental or affective state in the caregiving experience.29 The scale is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) disagree a lot to (5) agree a lot and assesses caregiver’s perceptions of benefits within the caregiving context such as feeling useful, appreciated, and finding meaning. Scores range from 9 to 45 and persons scoring higher indicate higher positive perception and gain from the caregiving experience. Tarlow et al29 tested PAC and reported an overall reliability of the instrument (Cronbach α = .89); convergent validity was evaluated using Spearman rank correlation between the total score on the PAC instrument and the 4-item Well-Being ordinal subscale (Cronbach α = .72) of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression. Cronbach α of PAC in the current study was .934.

Satisfaction With Life Scale

This 5-item questionnaire assesses the global life satisfaction of an individual and is measured on a 7-point Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7).30 The scale assesses a person’s conscious evaluative judgment of their life by their own criteria. The possible range of scores is 5 to 35, with higher scores suggesting higher life satisfaction. The SWLS has reported a good convergent validity (Cronbach α = .81) when compared with similar measure of satisfaction with life such as the Life Satisfaction Index-A.31 The SWLS had a Cronbach α of .877 in the present study.

Statistical Analyses

All descriptive statistics such as means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables were calculated using version 23 of SPSS Statistics (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). Pearson correlation matrix was calculated to provide an overview of the relationship between study variables. (SPSS PROCESS Macro, Andrew F. Hayes, Columbus, OH) 32 was used to test for a mediation effect of PAC on the association between satisfaction with life as independent variable and caregiver burden as dependent variable. The mediation analyses were controlled for sociodemographic variables including age, gender, ethnicity, education, marital status, and employment statues. Unstandardized indirect effects were computed for each of 1000 bootstrapped samples, and the 95% confidence interval (CI) was computed by determining the indirect effects at the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles. Significant mediation effect was set if the CIs did not contain 0.

Results

Majority of the sample were caregivers from the WiSE study (n = 179, 62.8%), females (n = 184, 64.6%), and belonged to the older age group (n = 210; 73.7%; mean = 47.2 years; SD = 10.87). Caregivers were predominantly of Chinese ethnicity (n = 160; 56.1%), with Malays and Indians making up 13.3% (n = 38) and 30.5% (n = 87), respectively. Most caregivers had tertiary level education (n = 95, 33.3%), were currently married (n = 173, 60.7%), and were largely employed (n = 216, 75.8%) during the time of study. The most common recipient of care were parents (n = 224, 78.6%). Table 1 displays the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample population. Pearson correlations between study variables are presented in Table 2. The mean scores for the scales were as follows: mean = 23.15 (SD = 15.98) for ZBI, mean = 34.55 (SD = 8.19) for PAC and mean = 23.56 (SD = 6.62) for SWLS. Results showed that ZBI, PAC, and SWLS were significantly associated with each other.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sample Distribution | |

| Recruited from WiSE | 179 (62.8) |

| Recruited from IMH | 106 (37.2) |

| Age Group (in years) | |

| 21-39 | 75 (26.3) |

| 40-65 | 210 (73.7) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 101 (35.4) |

| Female | 184 (64.6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Chinese | 160 (56.1) |

| Malay | 38 (13.3) |

| Indian | 87 (30.5) |

| Highest Education Level | |

| Primary | 9 (3.2) |

| Secondary | 76 (26.7) |

| ITE | 13 (4.6) |

| A Level | 17 (6.0) |

| Diploma | 74 (26.0) |

| Tertiary | 95 (33.3) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 85 (29.8) |

| Married | 173 (60.7) |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 27 (9.5) |

| Employment Status | |

| Employed | 216 (75.8) |

| Unemployed | 69 (24.2) |

| Type of Caregiver | |

| Family Members/Friends/Neighbours | 114 (40.0) |

| Paid Caregivers | 75 (26.3) |

| No Hands-on Care Required | 96 (33.7) |

| Relationship to Care Recipient | |

| Spouse | 18 (6.3) |

| Sibling | 2 (0.7) |

| Parent | 224 (78.6) |

| Other relatives/Others | 41 (14.4) |

Abbreviations: IMH, Institute of Mental Health; ITE, Institute of Technical Education; WiSE, Well-being of Singapore Elderly.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, Correlations of SWLS, ZBI, and PAC.

| Mean | SD | SWLS | ZBI | PAC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWLS | 23.56 | 6.62 | |||

| ZBI | 23.15 | 15.98 | −0.370a | ||

| PAC | 34.55 | 8.19 | 0.237a | −0.297a |

Abbreviations: PAC, positive aspects of caregiving; SD, standard deviation; SWLS, Satisfaction With Life Scale; ZBI, Zarit Burden Interview.

aCorrelation is significant at the .01 level (2-tailed).

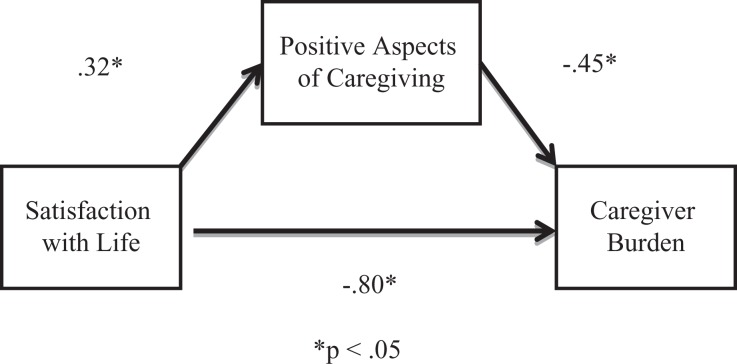

The relationship between satisfaction with life (SWLS) and caregiver burden (ZBI) was mediated by PAC. As Figure 1 illustrates, the unstandardized regression coefficient between PAC and SWLS was statistically significant, as was the unstandardized regression coefficient between PAC and ZBI. The unstandardized indirect effect was (0.32 x −0.45) = −0.14. The significance of this indirect effect was tested using bootstrapping procedures. The bootstrapped unstandardized indirect effect was −0.14, and the 95% CI ranged from −0.31 to −0.04. Thus, the indirect effect was statistically significant. Results from the mediation analysis are shown in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Mediation model with standardized coefficients.

Table 3.

Path Analysis Results on Mediation Model.

| Ba,b | SE | P | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Direct effect of satisfaction with life on ZBI | −0.80 | 0.15 | <.001 | (−1.09 to −0.50) |

| 2. Direct effect of satisfaction with life on PAC | 0.32 | 0.07 | <.001 | (0.18 to 0.46) |

| 3. Direct effect of positive aspects of caregiving on ZBI | −0.45 | 0.13 | <.005 | (−0.70 to −0.20) |

| 4. Indirect effect via positive aspects of caregiving | −0.14 | 0.07 | <.001 | (−0.31 to −0.04) |

| 5. Total effect of satisfaction with life and PAC | −0.94 | 0.15 | <.001 | (−1.22 to −0.65) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PAC, Positive Aspects of Caregiving; SE, Singapore elderly; ZBI, Zarit Burden Interview.

aControlled for age, gender, ethnicity, education, marital, employment status, and relationship to care recipient.

b Coefficients are unstandardized.

Discussion

The present study aimed to examine the positive caregiving pathway by considering life satisfaction and the burden of care on a sample of adults providing care to persons above the age of 60. Findings of the current study suggest that the perception of the burden of care can be explained by the caregiver’s appraisal of their mental or affective state in the context of their caregiving duties as well as their satisfaction with life.

The results of this study support the notion that PAC may play an important role on the burden of care. Folkman’s revised stress and coping model33 suggests that an unfavorable solution to stressful experiences or emotional outcomes may bring rise to meaningful coping mechanisms. As the burden of care increases, care providers employ measures such as revising their goals and spiritual beliefs, reappraising situations as more positive, and engaging in more constructive events. This, thus, provides caregivers a renewed sense of meaning in their roles as the condition of the care recipient progresses which could decrease burden and improve care. Evidence from the existent literature has consistently shown that PAC has a protective effect on the burden of care. A study by Hilgeman et al34 found that self-affirmation and outlook on life (factors of PAC) was stable across time and intervention in caregivers of Alzheimer disease, postulating that resilience, emotional stability, and well-being vary between individuals. Caregivers can experience high levels of satisfaction and gain self-esteem regardless of care burden.13 Tarlow et al’s29 scale was utilized in this study as its “rewards” construct is aligned with the present study objective of examining caregiver gains.35 Furthermore the scale has been validated in an Asian population36 and also in a sample of caregivers of older adults with limited functionality.37 The current study reflects high levels of perceived positive traits of caregiving, underlining its role as a protective factor in the overall perceived burden of care.

Subjective well-being comprises positive and negative affective appraisal and life satisfaction which is cognitively driven.38 Individuals with high levels of satisfaction often have good problem-solving skills, perform better at work, have meaningful relationships, show positive qualities such as generosity and forgiveness, are more resistant to stress, and have better overall physical and mental health.39 Previous findings have shown a negative association between burden and life satisfaction: people who feel that their role as caregivers is meaningful and beneficial had lower perceived burden of care13 and caregivers who had lower perceived burden engaged in more health-promoting behaviors.40 Similarly, caregivers with higher SWL were found to perceive more gain in their roles as caregivers, possess a more positive outlook on life, and receive better social support from family and friends.24 Additionally, identifying their caregiving duties favorably shows an inverse association with burden of care, which is consistent with past findings.41 Life satisfaction also mitigates the effects of stress and negative experiences. A study by Graham42 that looked at caregivers of long-term cancer survivors found that those who fulfilled their leisure needs had significantly lower levels of caregiver depression. On the other hand, individuals with lower satisfaction with life are at risk of psychological and social problems such as depression and anxiety as well as strained relationships with others. A study among caregivers of those with severe neuromotor and cognitive disorders found life satisfaction to be the best predictor of perceived burden,12 highlighting its importance in the overall caregiving experience.

The ZBI expresses family caregiver burden from 5 concepts that focus on the perceptions of caregivers: sacrifice/strain, inadequacy, embarrassment/anger, dependency, and loss of control.27 Several studies have shown that a positive experience of caregiving is dependent on the relationship of care provider and recipient, fewer hours of care, and when care is provided voluntarily.43 In a collectivist society such as Singapore, caregivers are more likely to experience notions of filial piety and obligation toward their duties which are intertwined by sociocultural norms.44–46 The cultural value of filial piety is unique concept in most Asian societies and plays a large role in the caregiving framework.47,48 Lai48 found that burden of care is indirectly affected by filial piety and serves as a protective function by reducing the negative effects of stressors. An additional factor that affects caregiver distress is through spiritual or religious coping. Caregivers who found comfort in their religion or spiritual beliefs had better relationships with their care recipients, which in turn was associated with lower depressive symptoms, better self-esteem, and self-care.49–51 As Singapore is still a largely religious country, this could play a role in mediating burden. However, results are inconclusive with some studies reporting little to no influence in the outcome of caregiver well-being.52 Another value that could affect the caregiving experience and caregiver burden is familism, which refers to strong feelings of attachment, dedication, and identification with family members. This is seen in highly collectivistic cultures where caregiving is deemed to be less of a burden. Despite this, results of studies examining this have been inconclusive,53,54 underlining the importance for more research in the cultural aspects of caregiving.

Maintaining a positive outlook on life is crucial to the well-being of the care provider. The caregiving experience necessitates the need for strong social support from both the family and community. Findings in research among caregivers have universally found an increased risk of depression owing to the responsibilities of care.55–58 Thus, it is imperative that health-care professionals assess and recognize caregiver burden. Early intervention could aid caregivers in their roles and identify support required to strike a balance between providing care and maintaining both physical and psychological well-being. Additionally, psychoeducational interventions and coping strategies can help alleviate caregiver distress. Finally, further studies into ethnic differences could shed light onto effective interventions, support, and coping methods to lessen the burden of care between ethnic groups of caregivers.

Limitations

The present study had certain limitations. The findings were based on a cross-sectional data and thus are unable to determine causation. As caregiving demands and response change over time, future research should include longitudinal studies. The inclusion criterion was limited to caregivers who were able to read and understand the English questionnaire, thus restricting generalizability for caregivers with less education. Part of the sample was participants who had previously participated in the WiSE study which had a response rate of 65.6%; there was, however, no attrition data collected for the present study.

The mediation analysis was based on a classical approach59 to determine the mediation effects of PAC on caregiver burden and vice versa. According to Baron and Kenny,59 the following criteria need to be satisfied for a variable to be considered a mediator: (1) the exposure variable should be associated with the mediator, (2) the mediator should be associated with the outcome, (3) the exposure should be associated with the outcome, and (4) when controlling for the mediator, the association between the exposure and outcome should be reduced or to be nonsignificant to indicate partial or complete mediation effects. However, these requirements (1-4) have been criticized by many researchers as they are often assessed using significance testing and assume no exposure–mediator interaction.60 Moreover, due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, we are unable to confirm the temporal ordering of the relationships between satisfaction, PAC, and caregiver burden that the mediation suggests; association does not necessarily imply the temporality. Thus, we recognize that this is an interesting area which can be studied and explored in future studies.

While the study examined positive caregiving characteristics among caregivers, it did not examine other potential mediators such as social support, caregiver resilience, or the quality of relationship between caregivers and care recipients. Also, the study did not have information on variables such as amount of caregiving and mental health status of care recipients (eg stage of dementia, behavioral problems) which affect caregiver burden. Finally, due to the sensitive nature of the study, participants included may present a social desirability bias in an effort to be viewed favorably.

Conclusions

Perceiving caregiving as a positive experience is essential in alleviating burden in persons providing care to older adults. Further research toward caregiving could also help shed light onto the protective factors of sociocultural norms. Findings of the current study underscore the importance of an optimistic outlook that can help manage the responsibilities of caregiving and offers a sense of significance and value to the caregivers. It is undeniable that efforts in reducing burden require further examination as it is critical to the psychological well-being of caregivers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the support from Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council under the Centre Grant Programme.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council under the Centre Grant Programme (Grant No.: NMRC/CG/004/2013).

References

- 1. Murray C, Barber R, Foreman K, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990-2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet. 2015;386(10009):2145–2191. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)61340-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing And Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gibson M, Houser A. Valuing the invaluable: a new look at the economic value of family caregiving. Issue Brief (Public Policy Institute (American Association of Retired Persons)). 2007;IB82(IB82):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abdin E, Subramaniam M, Achilla E, et al. The societal cost of dementia in Singapore: results from the WiSE study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51(2):439–449. doi:10.3233/jad-150930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feinberg L, Whitlatch C. Family caregivers and in-home respite options. J Gerontol Soc Work. 1999;30(3-4):9–28. doi:10.1300/j083v30n03_03. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(2):P112–P128. doi:10.1093/geronb/58.2.p112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bevans M, Sternberg E. Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. JAMA. 2012;307(4). doi:10.1001/jama.2012.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Adelman R, Tmanova L, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs M. Caregiver burden. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1052 doi:10.1001/jama.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yates M, Tennstedt S, Chang B. Contributors to and mediators of psychological well-being for informal caregivers. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999;54B(1):P12–P22. doi:10.1093/geronb/54b.1.p12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vaingankar J, Subramaniam M, Picco L, et al. Perceived unmet needs of informal caregivers of people with dementia in Singapore. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(10):1605–1619. doi:10.1017/s1041610213001051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Caldeira R, Neri A, Batistoni S, Cachioni M. Variables associated with the life satisfaction of elderly caregivers of chronically ill and dependent elderly relatives. Revista Brasileira de Geriatria e Gerontologia. 2017;20(4):502–515. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fianco A, Sartori R, Negri L, Lorini S, Valle G, Fave A. The relationship between burden and well-being among caregivers of Italian people diagnosed with severe neuromotor and cognitive disorders. Res Dev Disabil. 2015;39:43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haley W, LaMonde L, Han B, Burton A, Schonwetter R. Predictors of depression and life satisfaction among spousal caregivers in hospice: application of a stress process model. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(2):215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cohen C, Gold D, Shulman K, Zucchero C. Positive aspects in caregiving: an overlooked variable in research. Can J Aging. 1994;13(03):378–391. doi:10.1017/s071498080000619x. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cohen C, Colantonio A, Vernich L. Positive aspects of caregiving: rounding out the caregiver experience. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(2):184–188. doi:10.1002/gps.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beach S, Schulz R, Yee J, Jackson S. Negative and positive health effects of caring for a disabled spouse: longitudinal findings from the caregiver health effects study. Psychol Aging. 2000;15(2):259–271. doi:10.1037//0882-7974.15.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harmell A, Chattillion E, Roepke S, Mausbach B. A review of the psychobiology of dementia caregiving: a focus on resilience factors. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(3):219–224. doi:10.1007/s11920-011-0187-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Opinion Research Center. Long term care in America: Expectations and realities. Chicago, IL: The Associated Press and NORC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lawton M, Moss M, Kleban M, Glicksman A, Rovine M. A two-factor model of caregiving appraisal and psychological well-being. J Gerontol. 1991;46(4):P181–P189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lim J, Griva K, Goh J, Chionh H, Yap P. Coping strategies influence caregiver outcomes among Asian family caregivers of persons with dementia in Singapore. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25(1):34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kruithof W, Visser-Meily J, Post M. Positive caregiving experiences are associated with life satisfaction in spouses of stroke survivors. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;21(8):801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kulhara P, Kate N, Grover S, Nehra R. Positive aspects of caregiving in schizophrenia: a review. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(3):43 doi:10.5498/wjp.v2.i3.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abdollahpour I, Nedjat S, Salimi Y. Positive aspects of caregiving and caregiver burden: a study of caregivers of patients with dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2017;31(1):34–38. doi:10.1177/0891988717743590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chappell N, Reid R. Burden and well-being among caregivers: examining the distinction. Gerontologist. 2002;42(6):772–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Araújo L, Brandão D, Duarte N, et al. Life satisfaction and positive aspects of caregiving among centenarians proxies: the more dependent the better?. Gerontologist. 2015;55(suppl_2):657–657. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv344.05. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Subramaniam M, Chong SA, Vaingankar JA, et al. Prevalence of dementia in people aged 60 years and above: results from the WiSE study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45(4):1127–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zarit S, Reever K, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bachner Y, O’Rourke N. Reliability generalization of responses by care providers to the Zarit Burden Interview. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(6):678–685. doi:10.1080/13607860701529965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tarlow B, Wisniewski S, Belle S, Rubert M, Ory M, Gallagher-Thompson D. Positive aspects of caregiving. Research on Aging. 2004;26(4):429–453. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Diener ED, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pavot W, Diener E, Colvin C, Sandvik E. Further validation of the Satisfaction With Life Scale: evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. J Pers Assess. 1991;57(1):149–161. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hayes A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. 2nd ed New York, NY: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(8):1207–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hilgeman MM, Allen RS, DeCoster J, Burgio LD. Positive aspects of caregiving as a moderator of treatment outcome over 12 months. Psychol Aging. 2007;22(2):361–371. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stansfeld J, Stoner C, Wenborn J, Vernooij-Dassen M, Moniz-Cook E, Orrell M. Positive psychology outcome measures for family caregivers of people living with dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(08):1281–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lou V, Lau B, Cheung K. Positive aspects of caregiving (PAC): scale validation among Chinese dementia caregivers (CG). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60(2):299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Siow J, Chan A, Østbye T, Cheng G, Malhotra R. Validity and reliability of the Positive Aspects of Caregiving (PAC) Scale and development of Its Shorter Version (S-PAC) among family caregivers of older adults. Gerontologist. 2017;57(4):75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychol Bull. 2018;95(3):542–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Frisch M. Improving mental and physical health care through quality of life therapy and assessment In: Diener E, Rahtz D, eds. Advances in Quality of Life Theory and Research. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic; 2000:207–241. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sisk RJ. Caregiver burden and health promotion. Int J Nurs Stud. 2000;37(1):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hsiao C, Van Riper M. Individual and family adaptation in Taiwanese families of individuals with severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI). Res Nurs Health. 2009;32:307–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Graham A. Caregivers of long-term cancer survivors: the role leisure plays in improving psychological well-being (Master's Thesis). Waterloo, CA: University of Waterloo; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43. López J, López-Arrieta J, Crespo M. Factors associated with the positive impact of caring for elderly and dependent relatives. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2005;41(1):81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wong O, Chau B. The evolving role of filial piety in eldercare in Hong Kong. AJSSS. 2006;34(4):600–617. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: a meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2005;45(1):90–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lee Y, Sung K. Cultural differences in caregiving motivations for demented parents: Korean caregivers versus American caregivers. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1997;44(2):115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhan H, Montgomery R. Gender and elder care in China the influence of filial piety and structural constraints. Gender Soc. 2003;17(2):209–229. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lai D. Filial piety, caregiving appraisal, and caregiving burden. Research on Aging. 2010;32(2):200–223. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Murray-Swank A, Lucksted A, Medoff D, Yang Y, Wohlheiter K, Dixon L. Religiosity, psychosocial adjustment, and subjective burden of persons who care for those with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(3):361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pearce M, Singer J, Prigerson H. Religious coping among caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients. J Health Psychol. 2006;11(5):743–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chang B, Noonan A, Tennstedt S. The role of religion/spirituality in coping with caregiving for disabled elders. Gerontologist. 1998;38(4):463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Herrera A, Lee J, Nanyonjo R, Laufman L, Torres-Vigil I. Religious coping and caregiver well-being in Mexican–American families. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(1):84–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kim J, Knight B, Longmire C. The role of familism in stress and coping processes among African American and white dementia caregivers: effects on mental and physical health. Health Psychol. 2007;26(5):564–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Robinson G, Knight B. Preliminary study investigating acculturation, cultural values, and psychological distress in Latino caregivers of dementia patients. J Ment Health Aging. 2004;10(3):183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dunkin J, Anderson-Hanley C. Dementia caregiver burden: a review of the literature and guidelines for assessment and intervention. Neurology. 1998;51(issue 1, suppl 1):S53–S60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(2):250–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Grunfeld E. Family caregiver burden: results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. CMAJ. 2004;170(12):1795–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sherwood P, Given C, Given B, von Eye A. Caregiver burden and depressive symptoms. J Aging Health. 2005;17(2):125–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Baron R, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. MacKinnon D. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]