Abstract

Background

Public health strategies that target mosquito vectors, particularly pyrethroid long‐lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs), have been largely responsible for the substantial reduction in the number of people in Africa developing malaria. The spread of insecticide resistance in Anopheles mosquitoes threatens these impacts. One way to control insecticide‐resistant populations is by using insecticide synergists. Piperonyl butoxide (PBO) is a synergist that inhibits specific metabolic enzymes within mosquitoes and has been incorporated into pyrethroid‐LLINs to form pyrethroid‐PBO nets. Pyrethroid‐PBO nets are currently produced by four LLIN manufacturers and, following a recommendation from the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2017, are being included in distribution campaigns in countries. This review examines epidemiological and entomological evidence on whether the addition of PBO to LLINs improves their efficacy.

Objectives

1. Evaluate whether adding PBO to pyrethroid LLINs increases the epidemiological and entomological effectiveness of the nets.

2. Compare the effects of pyrethroid‐PBO nets currently in commercial development or on the market with their non‐PBO equivalent in relation to:

a. malaria infection (prevalence or incidence); b. entomological outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group (CIDG) Specialized Register; CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, CAB Abstracts, and two clinical trial registers (ClinicalTrials.gov and WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) up to 24 August 2018. We contacted organizations for unpublished data. We checked the reference lists of trials identified by the above methods.

Selection criteria

We included laboratory trials, experimental hut trials, village trials, and randomized clinical trials with mosquitoes from the Anopheles gambiae complex or Anopheles funestus group.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors assessed each trial for eligibility, extracted data, and determined the risk of bias for included trials. We resolved disagreements through discussion with a third review author. We analysed the data using Review Manager 5 and assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

Fifteen trials met the inclusion criteria: two laboratory trials, eight experimental hut trials, and five cluster‐randomized controlled village trials.

One village trial examined the effect of pyrethroid‐PBO nets on malaria infection prevalence in an area with highly pyrethroid‐resistant mosquitoes. The latest endpoint at 21 months post‐intervention showed that malaria prevalence probably decreased in the intervention arm (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.80; 1 trial, 1 comparison, moderate‐certainty evidence).

In highly pyrethroid‐resistant areas (< 30% mosquito mortality), in comparisons of unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets to unwashed standard‐LLINs, PBO nets resulted in higher mosquito mortality (risk ratio (RR) 1.84, 95% CI 1.60 to 2.11; 14,620 mosquitoes, 5 trials, 9 comparisons, high‐certainty evidence) and lower blood feeding success (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.71; 14,000 mosquitoes, 4 trials, 8 comparisons, high‐certainty evidence). However, in comparisons of washed pyrethroid‐PBO nets to washed LLINs we do not know if PBO nets have a greater effect on mosquito mortality (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.63; 10,268 mosquitoes, 4 trials, 5 comparisons, very low‐certainty evidence), although the washed pyrethroid‐PBO nets do decrease blood feeding success compared to standard‐LLINs (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.92; 9674 mosquitoes, 3 trials, 4 comparisons, high‐certainty evidence).

In areas where pyrethroid resistance is considered moderate (31% to 60% mosquito mortality), there may be little or no difference in effects of unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets compared to unwashed standard‐LLINs on mosquito mortality (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.54; 242 mosquitoes, 1 trial, 1 comparison, low‐certainty evidence), and there may be little or no difference in the effects on blood feeding success (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.13; 242 mosquitoes, 1 trial, 1 comparison, low‐certainty evidence). The same pattern is apparent for washed pyrethroid‐PBO nets compared to washed standard‐LLINs (mortality: RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.54; 329 mosquitoes, 1 trial, 1 comparison, low‐certainty evidence; blood feeding success: RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.13; 329 mosquitoes, 1 trial, 1 comparison, low‐certainty evidence).

In areas where pyrethroid resistance is low (61% to 90% mosquito mortality), there is probably little or no difference in the effect of unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets compared to unwashed standard‐LLINs on mosquito mortality (RR 1.10, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.16; 708 mosquitoes, 1 trial, 2 comparisons, moderate‐certainty evidence), but there is no evidence for an effect on blood feeding success (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.06 to 7.37; 708 mosquitoes, 1 trial, 2 comparisons, very low‐certainty evidence). For washed pyrethroid‐PBO nets compared to washed standard‐LLINs we do not know if there is any difference in mosquito mortality (RR 1.16, 96% CI 0.83 to 1.63; 878 mosquitoes, 1 trial, 2 comparisons, very low‐certainty evidence), but blood feeding may decrease (RR 1.50, 95% CI 0.89 to 2.54; 878 mosquitoes, 1 trial, 2 comparisons, low‐certainty evidence).

In areas were mosquito populations are susceptible to insecticides (> 90% mosquito mortality), there may be little or no difference in the effect of unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets compared to unwashed standard‐LLINs on mosquito mortality (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.64 to 2.26; 2791 mosquitoes, 2 trials, 2 comparisons, low‐certainty evidence). This is similar for washed nets (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.25; 2644 mosquitoes, 2 trials, 2 comparisons, low‐certainty evidence). We do not know if unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets have any effect on blood feeding success of susceptible mosquitoes (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.11 to 2.32; 2791 mosquitoes, 2 trials, 2 comparisons, very low‐certainty evidence). The same applies to washed nets (RR 1.28, 95% CI 0.81 to 2.04; 2644 mosquitoes, 2 trials, 2 comparisons, low‐certainty evidence).

In village trials comparing pyrethroid‐PBO nets to LLINs, there was no difference in sporozoite rate (4 trials, 5 comparison) and mosquito parity (3 trials, 4 comparisons).

Authors' conclusions

In areas of high insecticide resistance, pyrethroid‐PBO nets increase mosquito mortality and reduce blood feeding rates, and results from a single clinical trial demonstrate that this leads to lower malaria prevalence. Questions remain about the durability of PBO on nets, as the impact of pyrethroid‐PBO LLINs on mosquito mortality was not sustained over 20 washes in experimental hut trials. There is little evidence to support higher entomological efficacy of pyrethroid‐PBO nets in areas where the mosquitoes show lower levels of resistance to pyrethroids.

17 September 2019

Up to date

All studies incorporated from most recent search

All published trials found in the last search (24 Aug, 2018) were included, and we identified two ongoing studies

Plain language summary

Pyrethroid‐PBO nets to prevent malaria

Background

Bed nets treated with pyrethroid insecticides are an effective way to reduce malaria transmission and have been deployed across Africa. However, mosquitoes that spread malaria are now developing resistance to this type of insecticide. One way to overcome this resistance is to add another chemical, piperonyl butoxide (PBO), to the net. PBO is not an insecticide but blocks the substance (an enzyme) inside the mosquito that stops pyrethroids working.

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to find out if pyrethroid‐PBO nets add additional protection against malaria when compared to standard pyrethroid‐only nets.

Key messages

Pyrethroid‐PBO nets are more effective than standard pyrethroid‐only nets in killing mosquitoes and preventing them from blood feeding in areas where the mosquito populations are very resistant to pyrethroid insecticides (high‐certainty evidence). Pyrethroid‐PBO nets probably reduce the number of malaria infections (moderate‐certainty evidence), although further high‐quality studies measuring clinical outcomes are needed.

What was studied in the review?

We included 15 trials conducted between 2010 to 2018 that compared standard pyrethroid nets to pyrethroid‐PBO nets. These consisted of two laboratory trials, eight experimental hut trials that measured the impact of the pyrethroid‐PBO nets on a wild population of mosquitoes, and five village trials. Only one village trial measured the impact of pyrethroid‐PBO nets on malaria infection in humans; all other studies recorded the impact on mosquito populations. We analysed all studies to determine whether the pyrethroid‐PBO nets were better at killing mosquitoes and preventing them from blood feeding. For the single clinical trial, we examined whether pyrethroid‐PBO nets reduced the number of malaria infections. As the benefit of adding PBO to nets is likely to depend on the level of pyrethroid resistance in the mosquito population, we performed separate analyses for studies conducted in areas of high‐, medium‐, and low‐levels of pyrethroid resistance.

What are the main results of the review?

Where mosquitoes show high levels of resistance to pyrethroids, pyrethroid‐PBO nets perform better than standard pyrethroid‐only nets at killing mosquitoes and preventing them from blood feeding. As expected, this effect is not seen in areas where the mosquitoes show low or no resistance to the pyrethroid‐only insecticides. Only one trial looked at the impact of using pyrethroid‐PBO nets on the number of people infected with the malaria parasite. This trial, involving 3966 participants and conducted in an area where mosquitoes are very resistant to pyrethroids, found that fewer people were infected with malaria when the population used pyrethroid‐PBO nets compared to standard pyrethroid‐only nets.

How up to date is this review?

We searched for studies that had been published up to 24 August 2018.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Substantial progress has been made in reducing the burden of malaria in the 21st century. It is estimated that the clinical incidence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Africa dropped by 40% between 2000 and 2015, equating to the prevention of 663 million cases (Bhatt 2015; WHO‐GMP 2015). However progress has stalled in recent years (WHO 2017a). Targeting the mosquito vector has proven to be the most effective method of malaria prevention in Africa, with over two‐thirds of the malaria cases averted in the first 15 years of this century attributed to scale‐up in the use of long‐lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs), (Bhatt 2015). This method of malaria prevention is particularly effective in Africa where the major malaria vectors, Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles funestus, are largely endophagic (feed indoors) and endophilic (rest indoors after blood feeding).

Currently only one insecticide class, the pyrethroids, is commonly used to treat LLINs; pyrethroids have the required dual properties of low mammalian toxicity and rapid insecticidal activity (Zaim 2000), and their repellent or contact irritant effects may enhance the personal protection of LLINs. Unfortunately, resistance to pyrethroids is now widespread in African malaria vectors (Ranson 2016). This may be the result of mutations in target‐site proteins (target‐site resistance), (Ranson 2011; Ridl 2008), which results in reduced sensitivity to the insecticide or increased activity of detoxification enzymes (metabolic resistance) (Mitchell 2012; Stevenson 2011), or other as yet poorly‐described resistance mechanisms, or a combination of all or some of these factors. The evolution of insecticide resistance and its continuing spread threatens the operational success of malaria vector control interventions. The current impact of this resistance on malaria transmission is largely unquantified and will vary depending on the level of resistance, malaria endemicity, and proportion of the human population using LLINs (Churcher 2016). A recent multi‐country trial found no evidence that pyrethroid resistance reduced the personal protection provided by use of LLINs (Kleinschmidt 2018). However, it is generally accepted that resistance will eventually erode the efficacy of pyrethroid‐only LLINs and that innovation in the LLIN market is essential to maintain the efficacy of this preventative measure (MPAC 2016).

Description of the intervention

One way of controlling insecticide‐resistant mosquito populations is through the use of insecticide synergists. Synergists are generally non‐toxic and act by enhancing the potency of insecticides. Piperonyl butoxide (PBO) is a synergist that inhibits specific metabolic enzymes within mosquitoes, and has been incorporated into pyrethroid‐treated LLINs to form PBO‐combination nets (hereafter referred to as pyrethroid‐PBO nets). Insecticide‐synergist combination nets represent a new product class with the capacity to affect insecticide‐resistant populations. In 2017 the World Health Organization (WHO), gave pyrethroid‐PBO nets an interim endorsement as a new vector control class and recommended that countries consider deploying these nets in areas where pyrethroid resistance has been confirmed in the main malaria vectors (WHO‐GMP 2017a).

Currently there are five pyrethroid‐PBO nets in production: Olyset® Plus; PermaNet® 3.0; Veeralin® LN; and DawaPlus 3.0 and 4.0. Olyset Plus, which is manufactured by Sumitomo Chemical Company Ltd, is a polyethylene net treated with permethrin (20 g/kg ± 25%) and PBO (10 g/kg ± 25%) across the whole net (Sumitomo 2013). PermaNet 3.0, which is manufactured by Vestergaard Frandsen, is a mixed polyester (sides) polyethylene (roof) net treated with deltamethrin and PBO; PBO is only found on the roof of the net (25 g/kg ± 25%) and the concentration of deltamethrin varies depending on location (roof: 4.0 g/kg ± 25%) and yarn type (sides: 75 denier (thickness) yarn with 70 cm lower border 2.8 g/kg ± 25%, 100 denier (thickness) yarn without border 2.1 g/kg ± 25%; Vestergaard 2015). Veeralin LN, manufactured by Vector Control Innovations Private Ltd, is a polyethylene net treated with alpha‐cypermethrin (6.0 g/kg) and PBO (2.2 g/kg) across the whole net (WHOPES 2016). DawaPlus 3.0 and 4.0 are manufactured by Tana Netting, UAE, and contain PBO on the roof only (3.0), or on all sides (4.0); deltamethrin suspension concentrate (SC) is coated on knitted multi‐filament polyester fibres, at the target dose of 1.33 g/kg in 75 denier (thickness) yarn and 1 g/kg in 100 denier (thickness) yarn, corresponding to 40 mg of deltamethrin per m2, using a polymer as a binder. Ownership of DawaPlus 4.0 is currently in the process of transferring ownership to NRS Moon netting FZE (WHO 2018).

How the intervention might work

PBO inhibits metabolic enzyme families, in particular the cytochrome P450 enzymes that detoxify or sequester pyrethroids. Increased production of P450s is thought to be the most potent mechanism of pyrethroid resistance in malaria vectors, and pre‐exposure to PBO has been shown to restore susceptibility to pyrethroids in laboratory bioassays on multiple pyrethroid‐resistant vector populations (Churcher 2016).

Widespread use of conventional LLINs provides both personal and community protection from malaria (Bhatt 2015; Lengeler 2004). In areas where the mosquito populations are resistant to pyrethroids, experimental hut trials (as described in the ‘Types of studies' section), have shown that mosquito mortality rates and protection from blood feeding are substantially reduced when using conventional LLINs (Abílio 2015; Awolola 2014; Bobanga 2013; N'Guessan 2007; Riveron 2015; Yewhalaw 2012). The addition of PBO to pyrethroids in LLINs can restore the killing effects of LLINs in areas where this has been eroded by insecticide resistance. LLINs that contain PBO have been evaluated in multiple experimental hut trials across Africa (Adeogun 2012; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; N'Guessan 2010; Pennetier 2013; Tungu 2010). In most settings, the pyrethroid‐PBO nets resulted in higher rates of mosquito mortality and greater blood‐feeding inhibition than conventional LLINs, although the magnitude of this effect was variable. Village trials have measured the impact on sporozoite infection rates in mosquitoes with mixed results (Awolola 2014; Cisse 2017; Mzilahowa 2014; Stiles‐Ocran 2013). Recently, a cluster‐randomized trial in Tanzania demonstrated that use of pyrethroid‐PBO nets can reduce malaria prevalence in children (Protopopoff 2018).

Why it is important to do this review

All LLINs approved by the WHO Prequalification Team (formerly the WHO Pesticide Evaluation Scheme (WHOPES)), contain pyrethroids as the sole active ingredient. Five LLINs that contain PBO have interim approval (WHOPES 2016), and have been recognized as a new product class by WHO (WHO‐GMP 2017a). As pyrethroid‐PBO nets are generally more expensive than conventional LLINs, it is important to determine if they are superior to conventional LLINs and, if so, under what circumstances, to enable cost‐effectiveness trials to be performed to inform procurement decisions.

An Expert Review Group (ERG) commissioned by the WHO has recommended pyrethroid‐PBO nets be considered for use in areas where the major malaria vectors are resistant to pyrethroids (WHO‐GMP 2017a). This recommendation was largely based on a single randomized controlled trial of one pyrethroid‐PBO net type conducted in Tanzania (Protopopoff 2018), but also supported by a meta‐analysis of performance of pyrethroid‐PBO nets in experimental hut trials, which was used to parameterize a malaria transmission model to predict the public health benefit of pyrethroid‐PBO nets (Churcher 2016). However confusion remains over the settings in which pyrethroid‐PBO nets should be deployed. The WHO recommendation is that countries should consider deployment of this new product class in areas with intermediate levels of pyrethroid resistance but calls for further evidence, including data from a second clinical trial. This guidance has been adopted by some net providers; for example, the President's Malaria Initiative (PMI) (PMI 2018).

In an attempt to assess the evidence of the effectiveness of pyrethroid‐PBO nets against African malaria vectors in areas with differing levels of insecticide resistance, we have conducted a systematic review of all relevant trials and examined both epidemiological and entomological endpoints. We appreciate that the evaluation of PBO will depend on trials where the background insecticide and dose is the same in both intervention and control groups and are aware that most trials have evaluated pyrethroid‐PBO nets against pyrethroid‐only LLINs with different background insecticides and doses, which confounds the effects.

One of the problems with this research field is that pyrethroid‐PBO nets are commercial products. The pyrethroid‐PBO nets currently undergoing clinical trials have had additional alterations made to them, such as changing the concentration or rate at which the pyrethroid is released. However, these are the products for which policy decisions are needed, based on evidence related to their relative effectiveness. Thus, in this Cochrane Review, we sought direct evidence for PBO alone on the effectiveness of nets, and examined the evidence concerning the effectiveness of commercial products. During these comparisons, we considered other potential confounding factors.

Objectives

Evaluate whether adding PBO to pyrethroid LLINs increases the epidemiological and entomological effectiveness of the nets.

-

Compare the effects of pyrethroid‐PBO nets currently in commercial development or on the market with their non‐PBO equivalent in relation to:

malaria infection (prevalence or incidence);

entomological outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Objective 1

We included:

laboratory bioassay trials (for example, cone bioassays, tunnel tests);

experimental hut trials; and

village trials.

Objective 2 (a and b)

We included:

experimental hut trials;

village trials; and

clinical trials.

See Table 5 for WHOPES definitions in detail.

1. World Health Organization Pesticide Evaluation Scheme (WHOPES) classification.

| WHOPES Phase | Definition |

| WHOPES Phase I. Laboratory bioassays | Cone bioassays: these are studies that are conducted in the laboratory setting and use standard WHO protocols (WHO 2013, Section 2.2.1), where mosquitoes are exposed to a suitable LLIN (treated intervention or untreated control), for three minutes using a standard plastic WHO cone. Following net exposure, mosquitoes are transferred to a holding container and maintained on a sugar solution diet while entomological outcomes (mosquitoes knocked down one hour post‐exposure, and mosquito mortality 24 hours post‐exposure), are measured. Tunnel tests: these are studies conducted in the laboratory setting that use standard WHO protocols (WHO 2013, Section 2.2.2). Mosquitoes are released into a glass tunnel covered at each end with untreated netting. The intervention or control LLIN net sample is placed one‐third down the length of the tunnel and the net contains nine holes that enable mosquitoes to pass through. A suitable bait is immobilized in the shorter section of the tunnel where it is available for mosquito biting. Mosquitoes are released into the opposite end of the tunnel and must make contact with the net and locate holes before being able to feed on the bait. After 12 to 15 hours, mosquitoes are removed from both sections of the tunnel and entomological outcomes (the number of mosquitoes in each section, mortality, and blood‐feeding inhibition at the end of the assay and 24 hours post‐exposure), are recorded. Wire‐ball bioassays: these are studies conducted in the laboratory setting where mosquitoes are introduced into a wire‐ball frame that has been covered with either the intervention or control LLIN. Mosquitoes are exposed for three minutes, after which they are transferred to a holding container and entomological outcomes (mosquitoes knocked down one hour post‐exposure, and mosquito mortality 24 hours post‐exposure), are measured. |

| WHOPES Phase II. Experimental hut trials | WHOPES Phase II experimental hut trials are field trials conducted in Africa where wild mosquito populations or local colonized populations are evaluated. Volunteers or livestock sleep in experimental huts under a purposefully holed LLIN, with one person or animal per hut. Huts are designed to resemble local housing based on a West or East African design (WHO 2013; Section 3.3.1‐2). However they have identical design features, such as eave gaps or entry slits to allow mosquitoes to enter, and exit traps to capture exiting mosquitoes. LLINs and volunteers are randomly allocated to huts and rotated in a Latin square to avoid bias, with huts cleaned between rotations to avoid contamination. Several nets, including an untreated control net, can be tested at the same time. Dead and live mosquitoes are collected each morning from inside the net, inside the hut, and inside the exit traps. They are then scored as either blood‐fed or non‐blood‐fed, and either alive or dead, and live mosquitoes are maintained for a further 24 hours to assess delayed mosquito mortality. |

| WHOPES Phase III. Village trials | WHOPES Phase III village trials are village trials conducted in Africa where wild mosquito populations are evaluated. Villages chosen to be included in the study are similar in terms of size, housing structure, location, and the data available on the insecticide resistance status of the local malaria vectors. Households are assigned either conventional LLINs or PBO‐LLINs. Randomization can be at the household or village level. Adult mosquitoes are collected from the study houses and mosquito density is measured. An indication of malaria transmission is measured in the study sites either by recording infections in mosquitoes, malaria prevalence, or malaria incidence. |

Abbreviations: LLIN: long‐lasting insecticidal nets; PBO: pyrethroid‐piperonyl butoxide; WHOPES: World Health Organization Pesticide Evaluation Scheme

Types of participants

Mosquitoes

Anopheles gambiae complex or Anopheles funestus group. Included trials had to test a minimum of 50 mosquitoes per trial arm. We included all mosquito populations and examined the insecticide resistance level (measured using phenotypic resistance) during data analysis.

Humans

Adults and children living in malaria‐endemic areas.

Types of interventions

Intervention

Combination LLIN treated with both PBO and a pyrethroid insecticide. The LLINs must have received a minimum of interim‐WHO approval (Table 6), and LLINs had to be treated with a WHO‐recommended dose of pyrethroid (Table 7).

2. World Health Organization (WHO)‐recommended long‐lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs).

| Product name | Product type | Status of WHO recommendation |

| DawaPlus 2.0 | Deltamethrin coated on polyester | Interim |

| DawaPlus 3.0 | Combination of deltamethrin coated onto polyester (side panels), and deltamethrin and PBO incorporated into polyester (roof) | Interim |

| DawaPlus 4.0 | Deltamethrin and PBO incorporated into polyester | Interim |

| Duranet | Alpha‐cypermethrin incorporated into polyethylene | Full |

| Interceptor | Alpha‐cypermethrin coated on polyester | Full |

| Interceptor G2 | Alpha‐cypermethrin and chlorfenapyr incorporated into polyester | Interim |

| LifeNet | Deltamethrin incorporated into polypropylene | Interim |

| MAGNet | Alpha‐cypermethrin incorporated into polyethylene | Full |

| MiraNet | Alpha‐cypermethrin incorporated into polyethylene | Interim |

| Olyset Net | Permethrin incorporated into polyethylene | Full |

| Olyset Plus | Permethrin (20g/kg) and PBO (10g/kg) incorporated into polyethylene | Interim |

| Panda Net 2.0 | Deltamethrin incorporated into polyethylene | Interim |

| PermaNet 2.0 | Deltamethrin coated on polyester | Full |

| PermaNet 3.0 | Combination of deltamethrin coated on polyester with strengthened border (side panels), and deltamethrin and PBO incorporated into polyethylene (roof) | Interim |

| Royal Sentry | Alpha‐cypermethrin incorporated into polyethylene | Full |

| SafeNet | Alpha‐cypermethrin coated on polyester | Full |

| Veeralin | Alpha‐cypermethrin and PBO incorporated into polyethylene | Interim |

| Yahe | Deltamethrin coated on polyester | Interim |

| Yorkool | Deltamethrin coated on polyester | Full |

Abbreviations: LLIN: long‐lasting insecticidal nets; PBO: pyrethroid‐piperonyl butoxide; WHO: World Health Organization.

3. World Health Organization (WHO)‐recommended insecticide products for treatment of mosquito nets for malaria vector control.

| Insecticide | Formulation | Dosagea |

| Alpha‐cypermethrin | SC 10% | 20‐40 |

| Cyfluthrin | EW 5% | 50 |

| Deltamethrin | SC 1% WT 25% WT 25% + binderb | 15‐25 |

| Etofenprox | EW 10% | 200 |

| Lambda‐cyhalothrin | CS 2.5% | 10‐15 |

| Permethrin | EC 10% | 200‐500 |

Abbreviations: EC: emulsifiable concentrate; EW: emulsion, oil in water; CS: capsule suspension; SC: suspension concentrate; WT: water dispersible tablet. aActive ingredient/netting (mg/m2). bK‐O TAB 1‐2‐3.

Control

Conventional LLINs that contain pyrethroid only.

For objective 1 nets of the same fabric had to be treated with the same insecticide, dose and release rate as the intervention net to allow direct evaluation of the addition of PBO.

For objective 2 (a and b), nets could be treated with the same insecticide at different doses from the intervention net to allow critical appraisal of all pyrethroid‐PBO nets currently in development or on the market.

For both intervention and control arms, nets could be unholed, holed, unwashed or washed, providing the trials adhered to WHO guidelines (WHO 2013).

Types of outcome measures

Trials had to include at least one of the following outcomes to be eligible for inclusion: mosquito knock‐down, mosquito mortality, blood feeding, sporozoite rate, parasite presence, clinical malaria confirmation, not passed through net, deterrence, exophily, mosquito density, or parity rate.

Primary outcomes

Epidemiological

Parasite presence: presence of malaria parasites through microscopy of blood or Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs).

Clinical malaria confirmation: clinical diagnosis based on the participant's symptoms and on physical findings at examination.

Entomological

Mosquito mortality: immediate death or delayed death (up to 24 hours), or both, measured as a proportion of total mosquito number. A mosquito is classified as dead if it is immobile, cannot stand or fly, or shows no sign of life.

Mosquito knock‐down: mosquito ‘mortality' recorded one hour post‐insecticide exposure, termed ‘knock‐down' as some mosquitoes may recover during the 24‐hour recovery period before mosquito mortality is recorded at 24 hours post‐exposure.

Blood‐feeding success: number of mosquitoes that have blood‐fed (alive or dead).

Sporozoite rate: percentage of mosquitoes with sporozoites in salivary glands.

Secondary outcomes

Entomological

Not passed through net: the number of mosquitoes that do not pass through a holed pyrethroid‐PBO net to reach a human bait relative to a standard LLIN, using a tunnel test.

Deterrence: the number of mosquitoes that enter a hut that is using a pyrethroid‐PBO net relative to the number of mosquitoes found in a control hut that is using a standard LLIN (experimental hut trials only).

Exophily: the proportion of mosquitoes found in exit/veranda traps of a hut that is using a pyrethroid‐PBO net, relative to the control hut that is using a standard LLIN (experimental hut trials only).

Mosquito density: measured using all standard methods, such as window exit traps, indoor resting collections, floor sheet collections, pyrethrum spray catch, and light traps (village trials).

Parity rate: percentage of parous mosquitoes which are detected by mosquito ovary dissections (village trials).

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified all relevant trials regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress). We have presented the MEDLINE search strategy in Appendix 1.

Electronic searches

Vittoria Lutje, the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group (CIDG) Information Specialist, searched the following databases on 24 August 2018 using the search terms and strategy described in Appendix 1: the CIDG Specialized Register; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, included in the Cochrane Library (Issue 8 2018); MEDLINE (PubMed); Embase (OVID); Web of Science Core Collection, and CAB Abstracts. She also searched the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; www.who.int/ictrp/en/) and ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home) for trials in progress.

Searching other resources

We contacted the following organizations for unpublished data: the PMI; the Innovative Vector Control Consortium (IVCC); Vestergaard Frandsen; Sumitomo Chemical Company Ltd; Vector Control Innovations Private Ltd; Endura SpA; and WHOPES. We checked the reference lists of trials identified by the above methods.

Data collection and analysis

All analyses were stratified by trial design. We also performed analyses for the primary outcomes stratified by both trial design and mosquito insecticide resistance level where possible. In addition, for hut trials conducted in high‐resistance areas, we also performed analyses stratified by net type.

We determined whether mosquito populations are susceptible or resistant to pyrethroid insecticides based on WHO definitions (WHO 2016; Table 8). We used 24‐hour mosquito mortality to determine resistance status, however if this had been unavailable, we intended to use knock‐down 60 minutes after the end of the assay. We stratified resistant populations into low‐, moderate‐, or high‐prevalence resistance (Table 9), by dividing the resistant mosquitoes (that is, those with less than 90% mortality) into three equal groups, with the lower third being the most resistant and upper third the most susceptible.

4. Definition of resistance level.

| Outcome | Confirmed resistance | Suspected resistance | Susceptible | Unclassified |

| WHO mosquito mortalitya | < 90% | 90% to 97% | 98% to 100% | Unknown |

| CDC knock‐downb | < 90% | 80% to 97% | 98% to 100% | Unknown |

Abbreviations: CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; WHO: World Health Organization. aDefinition of resistance level based on mosquito mortality (%) after exposure to insecticide in a WHO diagnostic dose assay. bDefinition of resistance level based on mosquito mortality (%) after exposure to insecticide in a CDC bottle bioassay using the methodology, diagnostic doses, and diagnostic times recommended by each test respectively.

5. Stratification of resistance level.

| Outcome | Low | Moderate | High | Unclassified |

| Mosquito mortalitya | 61% to 90% | 31% to 60% | < 30% | Unknown |

a24‐hour post‐exposure mortality (%).

Selection of studies

Two review authors (KG and NL) independently screened titles and abstracts of all retrieved references based on the inclusion criteria (Table 10). We resolved any inconsistencies between the review authors' selections by discussion. If we were unable to reach an agreement, we consulted a third review author (HR). We retrieved the full‐text trial reports for all potentially relevant citations. Two review authors independently screened the full‐text articles and identified trials for inclusion, and identified and recorded reasons for exclusion of ineligible trials in a ‘Characteristics of excluded studies' table. We resolved any disagreements through discussion or, if required, consulted a third review author (HR). We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same trial so that each trial, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009).

6. Study inclusion screening form.

| Criteria | Assessment | Comments | ||

| Yes | No | Unclear | ||

| Mosquito population | ||||

| Did the study test Anopheles gambiae complex or Anopheles funestus group mosquitoes? | ↓ | — | ↓ | State mosquito species |

| Were a minimum of 50 mosquitoes tested per study arm? | ↓ | — | ↓ | |

| Intervention | ||||

| Did the study include an long‐lasting insecticidal net (LLIN) or insecticide‐treated net (ITN)? | ↓ | — | ↓ | State net LLIN or ITN |

Was the intervention net either of the following?

|

↓ | — | ↓ | State net type |

Was the control net either of the following?

|

↓ | — | ↓ | State which objective study meets |

| Study design | ||||

Was the study one of the following?

|

↓ | — | ↓ | State study type |

| For laboratory bioassay. Did the study use standard‐WHO protocol? | ↓ | — | ↓ | |

| For experimental hut study and village trial. Was the study conducted in Africa? | ↓ | — | ↓ | State country |

| Outcome | ||||

Did the study include at least one of the following outcome measures?

|

↓ | — | ↓ | |

| Decision | ||||

| Is the study eligible for inclusion? | — | — | ↓ | State reason(s) for exclusion |

| Discuss with authors | ||||

Abbreviations: ITN: insecticide‐treated net; LLIN: long‐lasting insecticidal net; PBO: piperonyl butoxide; WHO: World Health Organization.

Data extraction and management

After selection, we summarized all included trials according to the tables in Appendix 2. Two review authors (KG and NL) independently extracted data from the included trials using the pre‐designed data extraction form (Appendix 3). If data were missing from an included trial, we contacted the trial authors for further information. We entered data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) (Review Manager 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (KG and NL) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included trial using a set of predetermined criteria specific to each trial type adapted from Strode 2014 (Appendix 4). We assigned a classification of either low, high, or unclear risk of bias for each component. For all included trials we assessed whether any trial authors had submitted any conflicts of interest that may have biased the trial methodology or results.

Laboratory bioassays

For laboratory bioassays we assessed five criteria: comparability of mosquitoes between LLIN/pyrethroid‐PBO net arms (for example, all female, same age, and non‐blood‐fed), observers blinded, incomplete outcome data, raw data reported for both net treatments, and trial authors' conflicting interests.

Experimental hut trials

For experimental hut trials we assessed 11 criteria: comparability of mosquitoes between LLIN/pyrethroid‐PBO net arms (for example, species composition), collectors blinded, sleepers blinded, sleeper bias accounted for, treatment allocation, treatment rotation, standardized hut design, hut cleaning between treatments, incomplete outcome data, raw data reported, and trial authors' conflicting interests.

Village trials

We assessed 12 criteria for village trials: recruitment bias, comparability of mosquitoes between LLIN/pyrethroid‐PBO net households (for example, species composition), collectors blinded, household blinded, treatment allocation, allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data, raw data reported, clusters lost to follow‐up, selective reporting, adjusting for data clustering, and trial authors' conflicting interests.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data we presented the risk ratio (RR). There were no continuous or count data; however if there had been, we would have used the mean difference and rate ratios, respectively. We have presented all results with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Unit of analysis issues

For trials randomized by hut or village, we used the adjusted measure of effect reported in the paper if available. If not reported, we adjusted the effect estimate using an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC), and average cluster size (Higgins 2011, Section 16.3.4). If the included trial did not report the ICC value, we estimated the ICC value and investigated the impact of estimating the ICC in sensitivity analyses.

To adjust results of experimental hut trials for clustering, we treated each ‘hut and sleeper' combination as the unit of analysis, as each ‘hut and sleeper' combination was tested with each type of net, over a series of nights. We calculated effective sample sizes by estimating an ICC and corresponding design effect. We divided both the number of mosquitoes and the number experiencing the event by this design effect.

To adjust results of village trials for clustering (for which the trial authors had not adjusted the data themselves), we treated each village as the unit of analysis. We calculated effective sample sizes by estimating an ICC and corresponding design effect. Forest plots for both hut and village trials show the effective number of events after adjusting for clustering.

Dealing with missing data

In the case of missing data, we contacted the trial authors to retrieve this information. If we had identified trials where participants were lost to follow‐up, we would have investigated the impact of missing data via imputation using a best‐worst case scenario analysis.

Where information on mosquito insecticide resistance was not collected at the time of the trial, the review authors determined a suitable proxy. The proxy resistance data had to be from the same area, conducted within three years of the trial, and using the same insecticide, dose, and mosquito species. More than 50 mosquitoes per insecticide should have been tested using an appropriate control. Where no resistance data were available, we classed the resistance status as unclassified.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We presented the results of the included trials in forest plots, which we inspected visually to assess heterogeneity (that is, non‐overlapping CIs generally signify statistical heterogeneity). We also used the Chi2 test with a P value of less than 0.1 to indicate statistical heterogeneity. We quantified heterogeneity using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003), and we interpreted a value greater than 75% to indicate considerable heterogeneity (Deeks 2017).

Assessment of reporting biases

To analyse the possibility of publication bias, we intended to use funnel plots if 10 trials were included in any of the meta‐analyses. However, no analyses included 10 or more trials, so this was not applicable.

Data synthesis

Where appropriate, we pooled the results of the included trials using meta‐analysis. We stratified results by type of trial, mosquito resistance status and net type (i.e. product, for example Olyset Plus).

Three review authors (KG, NL, and MR) analysed the data using RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014), and we used the random‐effects model (if we detected heterogeneity; the I2 statistic value was more than 75%), or the fixed‐effect model (for no heterogeneity; the I2 statistic value was less than 75%). We would have not pooled trials in meta‐analysis if it was not clinically meaningful to do so, due to clinical or methodological heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed subgroup analyses according to whether nets were washed or unwashed.

Sensitivity analysis

We intended to perform sensitivity analyses to determine the effect of exclusion of trials that we considered to be at high risk of bias, however this was not applicable. We would also have performed a sensitivity analysis for missing data during imputation with best‐worst case scenarios, but again this was not applicable.

We performed sensitivity analyses to investigate the impact of estimating an ICC to adjust trial results for clustering. We performed analyses using ICCs of 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1. Since the results were robust to these adjustments, we used the most conservative ICC (0.1), and we adjusted all results from unadjusted cluster trials using this ICC. We have not presented analyses using the smaller ICCs (0.01 and 0.05).

Certainty of the evidence

We assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach (Schünemann 2013). We constructed ‘Summary of findings' tables using the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool (GDT) software (GRADEpro GDT 2015).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

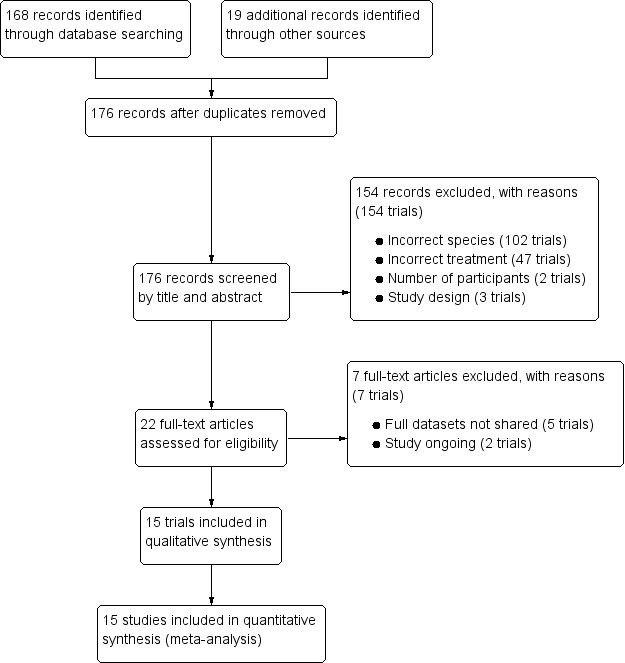

We identified 168 records through the electronic searches, and 19 additional records from other sources. We removed duplicates, leaving 175 records, and screened all articles for possible inclusion. After abstract and title screening, we excluded 154 obviously ineligible trials. We assessed 22 full‐text articles for eligibility and excluded seven articles for the following reasons: five trials did not share the full datasets and two studies are ongoing. Fifteen trials met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

Fifteen trials met the inclusion criteria, and we have described them in the ‘Characteristics of included studies' tables. Two trials were laboratory bioassays (Darriet 2011; Darriet 2013), eight trials were experimental hut trials (Bayili 2017 (Burkina Faso); Corbel 2010 (Burkina Faso, Benin, Cameroon); Koudou 2011 (Côte d'Ivoire); Moore 2016 (Tanzania); N'Guessan 2010 (Benin); Pennetier 2013 (Benin); Toé 2018 (Burkina Faso); Tungu 2010 (Tanzania)), and five trials were village trials (Awolola 2014 (Nigeria); Cisse 2017 (Mali); Mzilahowa 2014 (Malawi); Protopopoff 2018 (Tanzania); Stiles‐Ocran 2013 (Ghana)). All trials were conducted in Africa.

Interventions

Two trials compared a net treated with deltamethrin to a net treated with deltamethrin and PBO (Darriet 2011; Darriet 2013). Six trials compared Permanet 2.0 to Permanet 3.0 (Awolola 2014; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; N'Guessan 2010; Stiles‐Ocran 2013; Tungu 2010). Two trials compared Olyset Net to Olyset Plus (Pennetier 2013; Protopopoff 2018). One trial compared MAGNet LN to Veeralin LN (Moore 2016). Three trials compared both Olyset Net to Olyset Plus and Permanet 2.0 to Permanet 3.0 (Cisse 2017; Mzilahowa 2014; Toé 2018). One trial compared DawaPlus 2.0 to DawaPlus 3.0 and DawaPlus 4.0 (Bayili 2017).

Excluded studies

We assessed 22 full‐text articles for eligibility and excluded seven articles for the following reasons: five trials are awaiting classification because we were unable to obtain the full data sets after we contacted the trial authors (see ‘Characteristics of studies awaiting classification' table), and two trials are ongoing (see ‘Characteristics of ongoing studies' section).

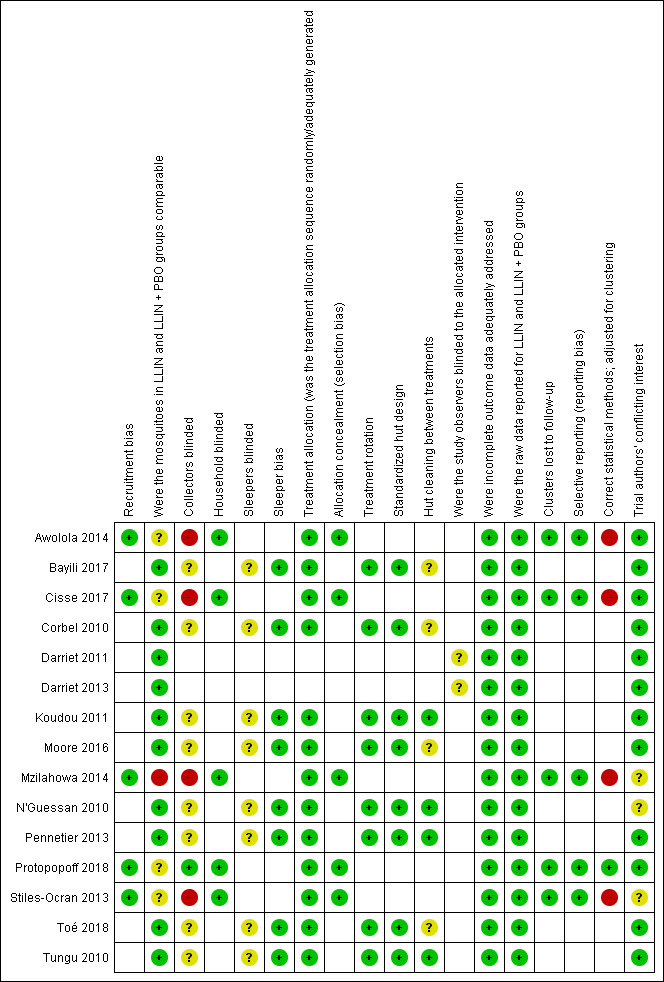

Risk of bias in included studies

We have provided a ‘Risk of bias' assessment summary in Figure 2. The criteria we used to assess risk of bias are in Appendix 5 (laboratory bioassays), Appendix 6 (experimental hut trials), and Appendix 7 (village trials).

2.

‘Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Recruitment bias

We assessed all five village trials as at low risk of bias. Four village trials were at low risk of recruitment bias as recruitment bias is related to human participants and so not applicable to this review (Awolola 2014; Cisse 2017; Mzilahowa 2014; Stiles‐Ocran 2013). We assessed one village trial as low risk as no participants were recruited after clusters had been randomized (Protopopoff 2018).

Mosquito group comparability

We judged the two laboratory bioassays at low risk of bias (Darriet 2011; Darriet 2013), as they used the same mosquito strain, and all eight experimental hut trials at low risk (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; Moore 2016; N'Guessan 2010; Pennetier 2013; Toé 2018; Tungu 2010), as the huts were situated in the same trial area and therefore accessible to the same mosquito populations. We judged four village trials at unclear risk (Awolola 2014; Cisse 2017; Protopopoff 2018; Stiles‐Ocran 2013), as the species composition and resistance status varied slightly between treatment arms. We deemed one village trial high risk (Mzilahowa 2014), as species and resistance data were not separated by village, and it was not possible to ascertain this from the information provided.

Blinding

We assessed the two laboratory trials (Darriet 2011; Darriet 2013), and eight hut trials (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; Moore 2016; N'Guessan 2010; Pennetier 2013; Toé 2018; Tungu 2010), as at unclear risk as they did not specify whether observers (lab trials), or collectors and sleepers (hut trials) were blinded. This is not standard protocol for these trial designs and is thought unlikely to affect the results. We judged four village trials at high risk of bias, as it was not stated if collectors were blinded, and this may affect searching effort during collections (Awolola 2014; Cisse 2017; Mzilahowa 2014; Stiles‐Ocran 2013). We classed one trial as low risk because collectors were masked to the treatment (Protopopoff 2018). For household blinding we judged all five village trials as low risk of bias. Four village trials did not state if households were blind to the intervention, however this was unlikely to influence the results (Awolola 2014; Cisse 2017; Mzilahowa 2014; Stiles‐Ocran 2013). We judged one village trial as low risk, as inhabitants and field collectors were blinded to intervention arms (Protopopoff 2018).

Sleeper bias

We assessed the eight hut trials at low risk for sleeper bias, as sleepers were rotated between huts following a Latin square design (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; Moore 2016; N'Guessan 2010; Pennetier 2013; Toé 2018; Tungu 2010).

Treatment allocation, rotation, and concealment

We assessed the eight hut trials at low risk for treatment allocation and rotation (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; Moore 2016; N'Guessan 2010; Pennetier 2013; Toé 2018; Tungu 2010), as treatments were rotated between huts following a Latin square design. We assessed five village trials at low risk for treatment allocation (Awolola 2014; Cisse 2017; Mzilahowa 2014; Protopopoff 2018; Stiles‐Ocran 2013), as villages were randomly assigned to treatment arms. We assessed all five village trials as low risk of bias for allocation concealment (Awolola 2014; Cisse 2017; Mzilahowa 2014; Protopopoff 2018; Stiles‐Ocran 2013).

Hut design

We assessed eight hut trials at low risk of bias, as huts were built to standard West‐ or East‐African specifications (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; N'Guessan 2010; Pennetier 2013; Toé 2018; Tungu 2010), or using modified but standardized designs (Moore 2016).

Cleaning

We assessed four hut trials at unclear risk as they did not state if huts were cleaned between treatment arms (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Moore 2016; Toé 2018; Tungu 2010). We assessed four at low risk, as cleaning was conducted between treatment rotations (Koudou 2011; N'Guessan 2010; Pennetier 2013; Tungu 2010).

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed all laboratory (Darriet 2011; Darriet 2013), hut (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; Moore 2016; N'Guessan 2010; Pennetier 2013; Toé 2018; Tungu 2010), and village trials (Awolola 2014; Cisse 2017; Mzilahowa 2014; Protopopoff 2018; Stiles‐Ocran 2013), as at low risk for both incomplete outcome data and raw data reporting, as there were no incomplete outcome data, or missing data were later provided by the trial authors. In cases where raw data were not reported, we were able to calculate them from the percentages and sample sizes given. When these data were not available, we did not include the trials.

Clustering bias

No clusters were lost to follow‐up in any of the village trials, therefore we assessed all village trials as at low risk of bias (Awolola 2014; Cisse 2017; Mzilahowa 2014; Protopopoff 2018; Stiles‐Ocran 2013). We assessed four village trials as at high risk of bias for statistical methods used, as they did not adjust for clustering (Awolola 2014; Cisse 2017; Mzilahowa 2014; Stiles‐Ocran 2013). We assessed one trial as low risk of bias, as it took clustering into account and adjusted for it in its statistical methods (Protopopoff 2018).

Selective reporting

We assessed all village trials as low risk of bias regarding selective reporting, as they appear to have reported all measured outcomes (Awolola 2014; Cisse 2017; Mzilahowa 2014; Protopopoff 2018; Stiles‐Ocran 2013).

Other potential sources of bias

Conflicting interests

We judged two lab trials (Darriet 2011; Darriet 2013), seven hut trials (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; Moore 2016; Pennetier 2013; Toé 2018; Tungu 2010), and three village trials (Awolola 2014; Cisse 2017; Protopopoff 2018), as at low risk as the trial authors reported no conflicting interests. We assessed one hut trial at unclear risk (N'Guessan 2010), as the trial authors stated that they had received funding from LLIN manufacturers when conducting the trials, and the same funders also provided comments on the manuscript. We assessed one village trial as unclear risk, as the trial authors did not state if there were conflicting interests or not (Mzilahowa 2014), and another one as unclear risk, as the trial was conducted to form part of the manufacturer's product dossier (Stiles‐Ocran 2013).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings for the main comparison. ‘Summary of findings' table 1.

| Pyrethroid‐piperonyl butoxide (PBO) nets compared to long‐lasting insecticidal nets (LLIN) for malaria control where insecticide resistance is high | ||||||

| Patient or population:Anopheles gambiae complex or Anopheles funestus group Setting: areas of high insecticide resistance Intervention: pyrethroid‐PBO nets Comparison: LLIN | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (trials) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with LLIN | Risk with pyrethroid‐PBO nets | |||||

| Prevalence of malaria | 527 per 1000a | 211 per 1000 (105 to 422)a | OR 0.40 (0.20 to 0.80) | 3966 people (1 trial, 1 comparison) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝

MODERATEb,c due to indirectness |

Prevalence of malaria is probably decreased with pyrethroid‐PBO nets compared to standard LLINs in areas of high insecticide resistance. |

| Mosquito mortality (unwashed nets) | 238 per 1000a | 438 per 1000 (381 to 503)a | RR 1.84 (1.60 to 2.11) | 14,620 mosquitoes (5 trials, 9 comparisons) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGHb | Mosquito mortality is increased with unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets compared to standard unwashed LLINs in areas of high insecticide resistance. |

| Mosquito mortality (washed nets) | 201 per 1000a | 242 per 1000 (177 to 328)a | RR 1.20 (0.88 to 1.63) | 10,268 mosquitoes (4 trials, 5 comparisons) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝

VERY LOWd,e due to imprecision and inconsistency |

We do not know if pyrethroid‐PBO nets have an effect on mosquito mortality in areas of high insecticide resistance when the nets have been washed. |

| Blood‐feeding success (unwashed nets) | 438 per 1000a | 263 per 1000 (241 to 311)a | RR 0.60 (0.50 to 0.71) |

14,000 mosquitoes (4 trials, 8 comparisons) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGHb | Mosquito blood‐feeding success is decreased with unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets compared to standard unwashed LLINs in areas of high insecticide resistance. |

| Blood‐feeding success (washed nets) | 494 per 1000a | 400 per 1000 (356 to 454)a | RR 0.81 (0.72 to 0.92) | 9674 mosquitoes (3 trials, 4 comparisons) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGHb | Mosquito blood‐feeding success is decreased with washed pyrethroid‐PBO nets compared to standard washed LLINs in areas of high insecticide resistance. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; LLIN: long‐lasting insecticidal nets; OR: odds ratio; PBO: pyrethroid‐piperonyl butoxide; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aOriginal numbers used in this table, however in pooled analysis events and total numbers were generated from cluster‐adjusted results which uses the effective sample size. Note that cluster adjustments do not change the point estimate of the effect size, just the standard error. bNot downgraded for imprecision: both best and worst case scenarios in this situation are important effects. cDowngraded by one for indirectness: the outcome is highly context specific and there is only one trial included here. dDowngraded by two for inconsistency due to unexplained qualitative heterogeneity. eDowngraded by one for imprecision due to wide CIs.

Summary of findings 2. ‘Summary of findings' table 2.

| Pyrethroid‐piperonyl butoxide (PBO) nets compared to long‐lasting insecticidal nets (LLIN) for malaria control where insecticide resistance is moderate | ||||||

| Patient or population:Anopheles gambiae complex or Anopheles funestus group Setting: areas of moderate insecticide resistance Intervention: pyrethroid‐PBO nets Comparison: LLIN | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of mosquitoes (experimental hut trials) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with LLIN | Risk with pyrethroid‐PBO nets | |||||

| Mosquito mortality (unwashed nets) | 439 per 1000a | 509 per 1000 (386 to 675)a | RR 1.16 (0.88 to 1.54) | 242 (1 trial, 1 comparison) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

LOWb,c,d due to imprecision and indirectness |

There may be little or no difference in the effect of unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets on mosquito mortality compared to standard unwashed LLINs in areas of moderate insecticide resistance. |

| Mosquito mortality (washed nets) | 287 per 1000a | 307 per 1000 (213 to 443)a | RR 1.07 (0.74 to 1.54) | 329 (1 trial, 1 comparison) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

LOWb,c,d due to imprecision and indirectness |

There may be little or no difference in the effect of washed pyrethroid‐PBO nets on mosquito mortality compared to standard washed LLINs (washed) in areas of moderate insecticide resistance. |

| Blood‐feeding success (unwashed nets) | 553 per 1000a | 481 per 1000 (370 to 624)a | RR 0.87 (0.67 to 1.13) | 242 (1 trial, 1 comparison) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

LOWb,c,d due to imprecision and indirectness |

There may be little or no difference in the effect of pyrethroid‐PBO nets (unwashed) on mosquito blood‐feeding success compared to standard LLINs in areas of moderate insecticide resistance. |

| Blood‐feeding success (washed nets) | 586 per 1000a | 533 per 1000 (434 to 662)a | RR 0.91 (0.74 to 1.13) | 329 (1 trial, 1 comparison) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

LOWb,c,d due to imprecision and indirectness |

There may be little or no difference in the effect of washed pyrethroid‐PBO nets on mosquito blood‐feeding success compared to standard washed LLINs in areas of moderate insecticide resistance. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; LLIN: long‐lasting insecticidal nets; PBO: pyrethroid‐piperonyl butoxide; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aOriginal numbers used in this table, however in pooled analysis, we generated events and total numbers from cluster‐adjusted results, which used the effective sample size. Note that cluster adjustments do not change the point estimate of the effect size, just the standard error. bNot downgraded for inconsistency as only one trial measured this outcome in this setting. cDowngraded by one for imprecision due to wide CIs. dDowngraded by one for indirectness: the outcome is highly context‐specific and there is only one trial included here.

Summary of findings 3. ‘Summary of findings' table 3.

| Pyrethroid‐piperonyl butoxide (PBO) nets compared to long‐lasting insecticidal nets (LLIN) for malaria control where insecticide resistance is low | ||||||

| Patient or population:Anopheles gambiae complex or Anopheles funestus group Setting: areas of low insecticide resistance Intervention: pyrethroid‐PBO nets Comparison: LLIN | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of mosquitoes (experimental hut trials) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with LLIN | Risk with pyrethroid‐PBO nets | |||||

| Mosquito mortality (unwashed nets) | 871 per 1000a | 958 per 1000 (914 to 1000)a | RR 1.10 (1.05 to 1.16) | 708 (1 trial, 2 comparisons) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝

MODERATEb due to imprecision |

There is probably little or no difference in the effect of unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets on mosquito mortality compared to standard unwashed LLINs in areas of low insecticide resistance. |

| Mosquito mortality (washed nets) | 620 per 1000a | 719 per 1000 (514 to 1000)a | RR 1.16 (0.83 to 1.63) | 878 (1 trial, 2 comparisons) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝

VERY LOWc,d due to imprecision and inconsistency |

We do not know if pyrethroid‐PBO nets have an effect on mosquito mortality in areas of low insecticide resistance when the nets have been washed. |

| Blood‐feeding success (unwashed nets) | 72 per 1000a | 48 per 1000 (4 to 529)a | RR 0.67 (0.06 to 7.37) | 708 (1 trial, 2 comparisons) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝

VERY LOWc,d due to imprecision and inconsistency |

We do not know if unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets have an effect on mosquito blood‐feeding success in areas of low insecticide resistance. |

| Blood‐feeding success (washed nets) | 149 per 1000a | 223 per 1000 (132 to 377)a | RR 1.50 (0.89 to 2.54) | 878 (1 trial, 2 comparisons) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

LOWd due to inconsistency |

Mosquito blood‐feeding success may decrease with washed pyrethroid‐PBO nets compared to standard washed LLINs in areas of low insecticide resistance. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; LLIN: long‐lasting insecticidal nets; PBO: pyrethroid‐piperonyl butoxide; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aOriginal numbers used in this table, however in pooled analysis events and total numbers were generated from cluster adjusted results which uses the effective sample size. Note that cluster adjustments do not change the point estimate of the effect size, just the standard error. bDowngraded by one for imprecision due to wide CIs. cDowngraded by one for inconsistency due to unexplained heterogeneity. dDowngraded by two for imprecision due to extremely wide CIs.

Summary of findings 4. ‘Summary of findings' table 4.

| Pyrethroid‐piperonyl butoxide (PBO) nets compared to long‐lasting insecticidal nets (LLIN) for malaria control where mosquitoes are susceptible | ||||||

|

Patient or population:Anopheles gambiae complex or Anopheles funestus group

Setting: areas of insecticide‐susceptible mosquitoes Intervention: pyrethroid‐PBO nets Comparison: LLIN | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of mosquitoes (experimental hut trials) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with LLIN | Risk with pyrethroid‐PBO nets | |||||

| Mosquito mortality (unwashed nets) | 392 per 1000a | 471 per 1000 (251 to 887)a | RR 1.20 (0.64 to 2.26) | 2791 (2 trials, 2 comparisons) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

LOWb due to imprecision |

There may be little or no difference in the effect of unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets on mosquito mortality compared to standard unwashed LLINs in areas of no insecticide resistance. |

| Mosquito mortality (washed nets) | 457 per 1000a | 489 per 1000 (420 to 571)a | RR 1.07 (0.92 to 1.25) | 2644 (2 trials, 2 comparisons) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

LOWb due to imprecision |

There may be little or no difference in the effect of washed pyrethroid‐PBO nets on mosquito mortality compared to standard washed LLINs in areas of no insecticide resistance. |

| Blood‐feeding success (unwashed nets) | 57 per 1000a | 29 per 1000 (6 to 132)a | RR 0.50 (0.11 to 2.32) | 2791 (2 trials, 2 comparisons) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝

VERY LOWb,c due to imprecision and inconsistency |

We do not know if unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets have an effect on mosquito blood‐feeding success in areas of no insecticide resistance. |

| Blood‐feeding success (washed nets) | 64 per 1000a | 82 per 1000 (52 to 131)a | RR 1.28 (0.81 to 2.04) | 2644 (2 trials, 2 comparisons) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

LOWb due to imprecision |

There may be little or no difference in the effect of washed pyrethroid‐PBO nets on mosquito blood‐feeding success compared to standard washed LLINs in areas of no insecticide resistance. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; LLIN: long‐lasting insecticidal nets; PBO: pyrethroid‐piperonyl butoxide; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aOriginal numbers used in this table, however in pooled analysis, events and total numbers were generated from cluster‐adjusted results, which use the effective sample size. Note that cluster adjustments do not change the point estimate of the effect size, just the standard error. bDowngraded by two for imprecision due to extremely wide CIs. cDowngraded by one for inconsistency due to unexplained heterogeneity.

Objective 1

Objective 1 was to evaluate whether adding PBO to pyrethroid‐LLINs increases the epidemiological and entomological effectiveness of bed nets.

Epidemiological results

None of the trials that met the inclusion criteria for Objective 1 measured parasite presence, or clinical malaria confirmation, in adults or children.

Entomological results

Two laboratory trials evaluated the impact of an insecticide‐treated net (ITN), impregnated with deltamethrin (a pyrethroid insecticide), only, compared to ITN plus PBO (PBO‐ITN), on mosquito mortality in an insecticide‐resistant laboratory strain (Darriet 2011; Darriet 2013). The pooled analysis showed substantially increased mosquito mortality when using pyrethroid‐PBO (RR 6.06, 95% CI 4.15 to 8.84; 558 mosquitoes, 2 trials; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pyrethroid‐PBO nets versus LLINs: laboratory bioassay (cone trials), Outcome 1 Mosquito mortality.

Objective 2

Objective 2 compared the effects of pyrethroid‐PBO nets currently in commercial development or on the market with their non‐PBO equivalent in relation to malaria infection and entomological outcomes.

Epidemiological results

One trial examined the effect of pyrethroid‐PBO nets on malaria infection prevalence (Protopopoff 2018). Overall the latest endpoint at 21 months after the intervention showed that malaria prevalence decreased in the intervention arm (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.80; 1 trial, 1 comparison; Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Commercial pyrethroid‐PBO nets versus commercial LLINs: village trials, Outcome 1 Prevalence of malaria.

Entomological results

Phase II experimental hut trials

Eight experimental hut trials (phase II trials), examined the effect of pyrethroid‐PBO nets on mosquito mortality, blood feeding, exophily, and deterrence (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; Moore 2016; N'Guessan 2010; Pennetier 2013; Toé 2018; Tungu 2010). We subgrouped the data by net washing, into unwashed and washed groups. Washed nets were all washed 20 times according to WHO specifications (WHO 2013). We pooled the results initially and then stratified them by insecticide resistance level and net type. One trial did not wash their nets and so did not report any data for the washed subgroup (Toé 2018). One trial did not introduce holes into the nets and so did not report blood‐feeding success data (Koudou 2011).

Pooled analysis

Pooled analysis of all experimental hut trials, using both unwashed (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; Moore 2016; N'Guessan 2010; Pennetier 2013; Toé 2018; Tungu 2010) and washed nets (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; Moore 2016; N'Guessan 2010; Pennetier 2013; Tungu 2010), found that pyrethroid‐PBO nets significantly increased mosquito mortality, by 36% (RR 1.36, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.54), and reduced blood‐feeding success by 24% (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.88). The magnitude of effect was reduced by net washing. Unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets increased mosquito mortality by 54% compared to unwashed LLINs, (RR 1.54, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.96; 8 trials, 15 comparisons; Analysis 2.1); when nets are washed this effect decreased to 14%, (RR 1.14, 95% 1.00 to 1.31; 7 trials, 11 comparisons; Analysis 2.1). Unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets reduced mosquito blood‐feeding success by 34% (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Moore 2016; N'Guessan 2010; Pennetier 2013; Toé 2018; Tungu 2010; RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.79; 7 trials, 14 comparisons; Analysis 2.2); however this effect was lost when nets were washed (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Moore 2016; N'Guessan 2010; Pennetier 2013; Tungu 2010; 6 trials, 10 comparisons; Analysis 2.2). There was no effect on mosquito exophily in either unwashed (8 trials, 15 comparisons; Analysis 2.3) or washed (7 trials, 11 comparisons; Analysis 2.3), groups. Mosquito deterrence data were presented relative to an untreated control and hence are not included as a forest plot. There was considerable variation in the deterrence rates but no clear relationship with resistance level, net type, or washing status (Table 11).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Commercial pyrethroid‐PBO nets versus commercial LLINs: hut trials, Outcome 1 Mosquito mortality (pooled) hut/night.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Commercial pyrethroid‐PBO nets versus commercial LLINs: hut trials, Outcome 2 Mosquito blood‐feeding success (pooled) hut/night.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Commercial pyrethroid‐PBO nets versus commercial LLINs: hut trials, Outcome 3 Mosquito exophily (pooled) hut/night.

7. Experimental hut trials: deterrence data.

| Study ID | Locality | Net type | Net washed | Total number in ITN hut | Total number in UTN hut | Deterrence (%) reported | Deterrence (%) calculated |

| Bayili 2017 | Vallée du Kou | DawaPlus 2.0 | No | 1548 | 1848 | 16.23 | 16.23 |

| Bayili 2017 | Vallée du Kou | DawaPlus 2.0 | Yes | 2155 | 1848 | 0 | ‐16.61 |

| Bayili 2017 | Vallée du Kou | DawaPlus 3.0 | No | 1365 | 1848 | 26.13 | 26.14 |

| Bayili 2017 | Vallée du Kou | DawaPlus 3.0 | Yes | 1981 | 1848 | 0 | ‐7.20 |

| Bayili 2017 | Vallée du Kou | DawaPlus 4.0 | No | 846 | 1848 | 54.22 | 54.22 |

| Bayili 2017 | Vallée du Kou | DawaPlus 4.0 | Yes | 1646 | 1848 | 10.93 | 10.93 |

| Corbel 2010 | Malanville | Permanet 2.0 | Yes | 195 | 285 | 31.58 | 31.58 |

| Corbel 2010 | Malanville | Permanet 3.0 | Yes | 210 | 285 | 26.32 | 26.32 |

| Corbel 2010 | Malanville | Permanet 2.0 | No | 243 | 285 | 14.74 | 14.74 |

| Corbel 2010 | Malanville | Permanet 3.0 | No | 214 | 285 | 24.91 | 24.91 |

| Corbel 2010 | Pitoa | Permanet 2.0 | Yes | 310 | 401 | 22.69 | 22.69 |

| Corbel 2010 | Pitoa | Permanet 3.0 | Yes | 163 | 401 | 59.35 | 59.35 |

| Corbel 2010 | Pitoa | Permanet 2.0 | No | 105 | 401 | 73.82 | 73.82 |

| Corbel 2010 | Pitoa | Permanet 3.0 | No | 146 | 401 | 63.59 | 63.59 |

| Corbel 2010 | Vallée du Kou | Permanet 2.0 | Yes | 788 | 908 | 13.22 | 13.22 |

| Corbel 2010 | Vallée du Kou | Permanet 3.0 | Yes | 724 | 908 | 20.26 | 20.26 |

| Corbel 2010 | Vallée du Kou | Permanet 2.0 | No | 329 | 908 | 63.77 | 63.77 |

| Corbel 2010 | Vallée du Kou | Permanet 3.0 | No | 463 | 908 | 49.01 | 49.01 |

| Koudou 2011 | Yaokoffikro | Permanet 3.0 | No | 303 | 796 | 62.1 | 61.93 |

| Koudou 2011 | Yaokoffikro | Permanet 2.0 | No | 317 | 796 | 60.4 | 60.18 |

| Koudou 2011 | Yaokoffikro | Permanet 3.0 | Yes | 313 | 796 | 60.1 | 60.68 |

| Koudou 2011 | Yaokoffikro | Permanet 2.0 | Yes | 281 | 796 | 64.4 | 64.70 |

| Moore 2016 | Ifakara | Veeralin LN | No | 722 | 810 | 11 | 10.86 |

| Moore 2016 | Ifakara | Veeralin LN | Yes | 727 | 810 | 10 | 10.25 |

| Moore 2016 | Ifakara | MAGNet LN | No | 1070 | 810 | 0 | ‐32.10 |

| Moore 2016 | Ifakara | MAGNet LN | Yes | 773 | 810 | 5 | 4.57 |

| Moore 2016 | Ifakara | Veeralin LN | No | 89 | 170 | 48 | 47.65 |

| Moore 2016 | Ifakara | Veeralin LN | Yes | 85 | 170 | 50 | 50.00 |

| Moore 2016 | Ifakara | MAGNet LN | No | 114 | 170 | 33 | 32.94 |

| Moore 2016 | Ifakara | MAGNet LN | Yes | 103 | 170 | 39 | 39.41 |

| N'Guessan 2010 | Akron | Permanet 3.0 | No | 128 | 185 | 31 | 30.81 |

| N'Guessan 2010 | Akron | Permanet 3.0 | Yes | 155 | 185 | NR | 16.22 |

| N'Guessan 2010 | Akron | Permanet 2.0 | No | 114 | 185 | 38 | 38.38 |

| N'Guessan 2010 | Akron | Permanet 2.0 | Yes | 174 | 185 | NR | 5.95 |

| Pennetier 2013 | Malanville | Olyset Plus | No | 67 | 69 | NR | 2.90 |

| Pennetier 2013 | Malanville | Olyset Plus | Yes | 101 | 69 | NR | ‐46.38 |

| Pennetier 2013 | Malanville | Olyset Net | No | 96 | 69 | NR | ‐39.13 |

| Pennetier 2013 | Malanville | Olyset Net | Yes | 124 | 69 | NR | ‐79.71 |

| Toé 2018 | Tengrela | Olyset Net | No | 923 | 480 | ‐92.29 | ‐92.29 |

| Toé 2018 | Tengrela | Olyset Plus | No | 695 | 480 | ‐44.79 | ‐44.79 |

| Toé 2018 | Tengrela | Permanet 2.0 | No | 858 | 480 | ‐78.75 | ‐78.75 |

| Toé 2018 | Tengrela | Permanet 3.0 | No | 794 | 480 | ‐65.42 | ‐65.42 |

| Toé 2018 | VK5 | Olyset Net | No | 1458 | 1095 | ‐33.15 | ‐33.15 |

| Toé 2018 | VK5 | Olyset Plus | No | 1278 | 1095 | ‐16.71 | ‐16.71 |

| Toé 2018 | VK5 | Permanet 2.0 | No | 1075 | 1095 | 1.83 | 1.83 |

| Toé 2018 | VK5 | Permanet 3.0 | No | 657 | 1095 | 40 | 40.00 |

| Tungu 2010 | Zeneti | PermaNet 3.0 | No | 425 | 723 | 41 | 41.22 |

| Tungu 2010 | Zeneti | PermaNet 2.0 | No | 574 | 723 | 21 | 20.61 |

| Tungu 2010 | Zeneti | PermaNet 3.0 | Yes | 558 | 723 | 23 | 22.82 |

| Tungu 2010 | Zeneti | PermaNet 2.0 | Yes | 586 | 723 | 19 | 18.95 |

Abbreviations: ITN: insecticide‐treated net; LLIN: long‐lasting insecticidal net; NR: not reported; PBO: piperonyl butoxide; UTN: untreated net; WHO: World Health Organization.

There was considerable heterogeneity in this pooled analysis, particularly for estimates of mortality. We therefore performed a pre‐specified, stratified analysis, dividing the results into trials conducted in areas of low, moderate, or high resistance in the Anopheles population.

Stratified analysis: mosquito resistance status

We used the WHO and CDC definitions of mosquito mortality, from WHO tube assays or CDC bottle tests (Table 8) to classify mosquito resistance. Both tests define mosquitoes as resistant when mortality is less than 90%. We further stratified resistance based on the following mortality levels: < 30%, high resistance; 31% to 60%, moderate resistance; 61% to 90%, low resistance (Table 9). When resistance data were not collected at the time of the trial, we identified a suitable proxy based on previously described criteria (see ‘Dealing with missing data' section); when we could not identify a suitable proxy, we classed the trial as ‘unclassified' and did not include it in the resistance stratification.

Five trials were conducted in four areas where mosquito populations exhibited high resistance to pyrethroids (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; Pennetier 2013; Toé 2018). Under these conditions unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO nets increased mosquito mortality by 84% in comparison to unwashed LLINs (RR 1.84, 95% CI 1.60 to 2.11; 5 trials, 9 comparisons; Analysis 2.4), however this effect was lost when nets were washed (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Koudou 2011; Pennetier 2013; 4 trials, 5 comparisons; Analysis 2.4). Blood‐feeding success was reduced by 40% in unwashed pyrethroid‐PBO‐net groups compared to unwashed LLINs (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Pennetier 2013; Toé 2018; RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.71; 4 trials, 8 comparisons; Analysis 2.5), and by 19% when nets were washed (Bayili 2017; Corbel 2010; Pennetier 2013; RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.92; 3 trials, 4 comparisons; Analysis 2.5).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Commercial pyrethroid‐PBO nets versus commercial LLINs: hut trials, Outcome 4 Mosquito mortality (high resistance) hut/night.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Commercial pyrethroid‐PBO nets versus commercial LLINs: hut trials, Outcome 5 Mosquito blood‐feeding success (high resistance) hut/night.

One trial in one site was conducted in an area with moderate insecticide resistance (N'Guessan 2010). No effect on mosquito mortality (1 trial, 1 comparison; Analysis 2.6) or on blood‐feeding success (1 trial, 1 comparison; Analysis 2.7) was observed in either washed or unwashed treatments.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Commercial pyrethroid‐PBO nets versus commercial LLINs: hut trials, Outcome 6 Mosquito mortality (moderate resistance) hut/night.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Commercial pyrethroid‐PBO nets versus commercial LLINs: hut trials, Outcome 7 Mosquito blood‐feeding success (moderate resistance) hut/night.