Summary

This case report describes a 54-year-old man presenting with loss of consciousness due to acquired long QT syndrome shortly after flecainide therapy. The patient had no common risk factors for acquired long QT syndrome. Prior to onset of ventricular tachycardia, bradyarrhythmia and short-long-short sequence were observed with a prolonged QT interval of 710 ms. However, the morphology of induced tachycardia was uniform rather than torsades de pointes. We presumed that the properties of flecainide, such as slowing conduction, contribute partly in a use-dependent manner to development of uniform tachycardia. In addition, we believe that prolongation of QT by flecainide is exceedingly rare; however, it may be one of the mechanisms of flecainide-induced proarrhythmia.

Keywords: Flecainide, Long QT syndrome, Ventricular tachycardia

Introduction

Flecainide is a potent sodium-channel blocker, with slow onset and offset kinetics [1]. It is known as a safe antiarrhythmic agent in patients with normal hearts and is used widely in the treatment of atrial fibrillation (AF). However, proarrhythmia by flecainide may be fatal and may well have been described in patients with structural heart disease. Acquired long QT syndrome (LQTs) is not included as one of these proarrhythmic episodes and is very uncommon because effects of flecainide on repolarization are minimal [2]. Acquired LQTs is usually accompanied by torsades de pointes and is induced by concomitant risk factors. These proarrhythmic episodes can result in sudden death upon degeneration to ventricular fibrillation. However, the present case report showed prolongation of QT interval by flecainide without any usual risk factors. In addition, it eventually presented with uniform ventricular tachycardia (VT) rather than torsades de pointes. We believe that the present case is a very rare one, demonstrating a direct relationship between flecainide and acquired LQTs.

Case report

A 54-year-old man who had a history of hypertension was referred for palpitation and chest discomfort lasting 5 days. He had received treatment with aspirin 200 mg and perindopril 4 mg a day at a primary clinic. He had no prior history of syncope or familial history of syncope, cardiac arrest, or sudden cardiac death. Findings from physical examination were unremarkable and an initial 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed AF with rapid ventricular response. A chest X-ray and chemistry data, including serum electrolytes, cardiac enzyme, brain natriuretic peptide, and thyroid function test were normal. Propranolol 120 mg a day was prescribed for 3 days and a follow up ECG demonstrated AF of 88 beats per minute (bpm) (Fig. 1). Both QRS width and corrected QT (QTc) interval were normal, at 95 ms and 438 ms, respectively. Scintigraphic myocardial perfusion imaging showed a normal stress study. On transthoracic echocardiography, both ventricles were found to be of normal size and thickness, and the left ventricular ejection fraction was 52% without regional wall motion abnormality. The patient was prescribed flecainide of 200 mg and atenolol 25 mg a day.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram demonstrating atrial fibrillation after rate control (rate = 88 bpm, QRS duration = 95 ms, and QTc interval = 438 ms).

Five days later, he was admitted to the emergency department due to repetitive loss of consciousness. The initial ECG revealed uniform, sine wave-like tachyarrhythmia (cycle length = 440 ms) with a right bundle branch block pattern and a left axis deviation (Fig. 2A). After electrical cardioversion of 200J, a slow escape rhythm with ventricular premature beats was observed on ECG monitoring. During bradycardia, a negative T wave was observed on the surface ECG and QTc interval reached 680 ms. Multiple episodes of sustained or nonsustained tachyarrhythmia with the same form occurred in succession by ventricular premature beats with a short-long-short sequence (Fig. 2B). Chemistry data, including cardiac enzymes and serum sodium, potassium, magnesium, and calcium were still normal. After continuous isoproterenol infusion, bradycardia showed improvement and tachyarrhythmia was suppressed. On follow-up ECG, prolonged QTc interval (QTc = 556 ms) and T wave inversion were still noted during normal sinus rhythm (rate = 71 bpm) (Fig. 3). Coronary angiography was unremarkable and echocardiography showed a slightly decreased left ventricular ejection fraction of 45% without other interval changes from the initial study. Flecainide was discontinued; one week later, AF was still noted but QTc interval was normalized. He was discharged with amiodarone 100 mg and diltiazem 180 mg a day after pacemaker implantation for prevention of sinus dysfunction.

Figure 2.

(A) Uniform, wide QRS tachycardia (cycle length = 440 ms) with a right bundle branch block pattern and left axis deviation. This sine wave-like electrical activity may result from a slow binding–unbinding kinetic of flecainide. (B) A prolonged QT interval (QT interval = 710 ms and QTc interval = 680 ms) and a short-long-short sequence followed by nonsustained ventricular tachycardia.

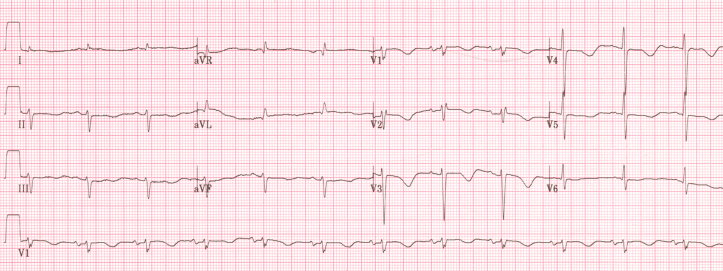

Figure 3.

(A) Follow-up electrocardiogram during normal sinus rhythm. The corrected QT interval was prolonged (rate = 71 bpm, QRS duration = 102 ms, and QTc interval = 556 ms).

Discussion

Flecainide is known as a safe antiarrhythmic agent in patients with normal hearts and is used widely in treatment of AF. However, the proarrhythmic event by flecainide may be fatal and includes a paradoxical increase in ventricular rate in atrial tachyarrhythmia, reduced excitability of myocardium, and increased mortality in patients with prior myocardial ischemia [1]. Aberrant conduction on supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) with 1:1 conduction is a well-known proarrhythmia in flecainide use and it should be differentiated from VT. In our case, diagnosis of VT from the initial ECG was not easy to confirm. We determined that the mode of tachycardia initiation on following episodes favored VT rather than SVT with aberrancy.

However, prolongation of QT interval without QRS widening by flecainide is an uncommon proarrhythmic episode [2]. Prolongation of QT interval is usually related to electrolyte abnormalities, bradycardia, and exposure to certain drugs, particularly class Ia and III antiarrhythmics [1]. In the present case, QT interval was prolonged without these risk factors and actually resulted in VT. Accompaniment of sinus node dysfunction and bradyarrhythmia was initially observed; however, QT prolongation was still observed after recovery of normal sinus rhythm. We did not analyze genetic mutation of ion channels. This limitation allows us to speculate about subclinical LQTs. However, the possibility of congenital LQTs in the present case seems to be low, because oral flecainide has been known to usually shorten QT interval rather than to prolong it in LQT3 patients with the genetic defect of SCN5A, and proarrhythmic sensitivity would be explained by a phenotype combining LQT3 and Brugada syndrome [3]. Also, in a case of KCNQ1 gene mutation, male patients with LQT1 who are older than 25 years of age have been known to be exceptional, because very seldom does a first event occur any later in this population [4]. Another assumption is about genetic polymorphism of drug metabolism. It may help to explain the cause of adverse events under the usual dosage of flecainide, although we did not measure the serum level of flecainide. In the rare patients with lack of active CYP2D6, flecainide can accumulate to toxic plasma concentrations [5]. Review of prior literature found only a few case reports demonstrating a direct relationship between flecainide therapy and acquired LQTs and torsades de pointes [2], [6].

Acquired LQTs is usually bradycardia-dependent and short-long-short sequences are frequently observed at arrhythmia onset [7], [8]. Typically triggered activity due to early after depolarizations (EAD) is initiated by a short-long-short sequence of complexes [7]. As in the present case, the current role of triggered activity by EAD has been more as an initiator of torsades de pointes in acquired LQTs [9]. All of the prior reports showed flecainide-induced torsades de pointes under the same conditions [2], [6]. However, our case showed uniform, sine-wave like VT at onset and during maintenance of tachycardia, even though these electrical activities were observed prior to onset of tachycardia. There may be some explanations. Some investigators have demonstrated that EAD could give rise to a uniform tachycardia as well, and that there may be no obligatory link between EADs and torsades de pointes [7], [8]. In addition, we assumed that the electrophysiological property of flecainide may give rise to uniform VT. Flecainide blocks the fast sodium channel in a use-dependent manner and primarily slows down conduction by depression of the maximum rate of rise of depolarization of the action potential with minimal effect on refractoriness [10]. Incessant uniform VT can develop with markedly widened QRS complexes and a sine-wave morphology by antiarrhythmic agents that slow ventricular conduction, particularly by class IA or IC [9], [10]. We would like to explain the main culprit perpetuating this arrhythmia as ventricular macroreentry associated with functional block that can be a result of the slowing of conduction in a use-dependent manner by flecainide.

In the present case, we reported on an unusual proarrhythmic episode in a patient who had undergone flecainide therapy. Without any risk factors, our case demonstrated that flecainide treatment can result in development of acquired LQTs with uniform VT in a patient with no history of VT. We believe that prolongation of QT by flecainide is exceedingly rare; however, it may be one of the mechanisms of flecainide-induced proarrhythmia.

References

- 1.Darbar D. Standard antiarrhythmic drugs. In: Zipes D.P., Jalife J., editors. Cardiac electrophysiology: from cell to bedside. 5th ed. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 2009. pp. 962–968. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nogalas Asensio J.M., Sanchez N.M., Vecino L.J.D., Mariscal C.V., Lopez-Minguez J.R., Herrera A.M. Torsades-de-pointes in a patient under flecainide treatment, an unusual case of proarrhythmicity. Int J Cardiol. 2007;114:e65–e67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.07.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckardt L., Breithardt G. Drug-induced ventricular tachycardia. In: Zipes D.P., Jalife J., editors. Cardiac electrophysiology: from cell to bedside. 5th ed. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 2009. p. 769. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz P.J., Crotti L. Long QT and short QT syndromes. In: Zipes D.P., Jalife J., editors. Cardiac electrophysiology: from cell to bedside. 5th ed. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 2009. p. 740. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckmann J., Hertrampf R., Gudert-Remy U., Mikus G., Gross A.S., Eichelbaum M. Is there a genetic factor in flecainide toxicity? BMJ. 1988;297:1316. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6659.1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thevenin J., Da Costa A., Roche F., Romeyer C., Messier M., Isaaz K. Flecainide induced ventricular tachycardia (torsades de pointes) Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2003;26:1907–1908. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cranefield P.F., Aronson R.S. Torsades de pointes and other pause-induced ventricular tachycardias; the short-long-short sequence and early afterdepolarizations. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1988;11:670–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1988.tb06016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surawicz B. Torsades de pointes: unanswered questions. J Nippon Med Sch. 2002;69:218–223. doi: 10.1272/jnms.69.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heist E.K., Ruskin J.N. Drug-induced arrhythmia. Circulation. 2010;122:1426–1435. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.894725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Josephson M.E. Evaluation of antiarrhythmic agents. In: Josephson M.E., editor. Clinical cardiac electrophysiology: techniques and interpretations. 4th ed. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 2008. pp. 643–683. [Google Scholar]