ABSTRACT

Continuous labor support by a trained doula has proven benefits and is recognized as an effective strategy to improve maternal and infant health, enhance engagement and satisfaction with maternity care, and reduce spending. Community-based doula programs can also reduce or eliminate health disparities by providing support to women most at risk for poor outcomes. The most effective way to increase use of this evidence-based service would be to eliminate cost barriers. Key recommendations identify numerous pathways to pursue Medicaid and private insurance coverage of doula care. This comprehensive and up-to-date inventory of reimbursement options provides the doula, childbirth, and quality communities, as well as policy makers, with many approaches to increasing access to this high-value form of care.

Keywords: doula, continuous labor support, insurance, Medicaid, coverage

“One of the most effective tools to improve labor and delivery outcomes is the continuous presence of support personnel, such as a doula.”

—Caughey, Cahill, Guise, and Rouse (2014)

One of the most effective tools to improve labor and delivery outcomes is the continuous presence of support personnel, such as a doula.

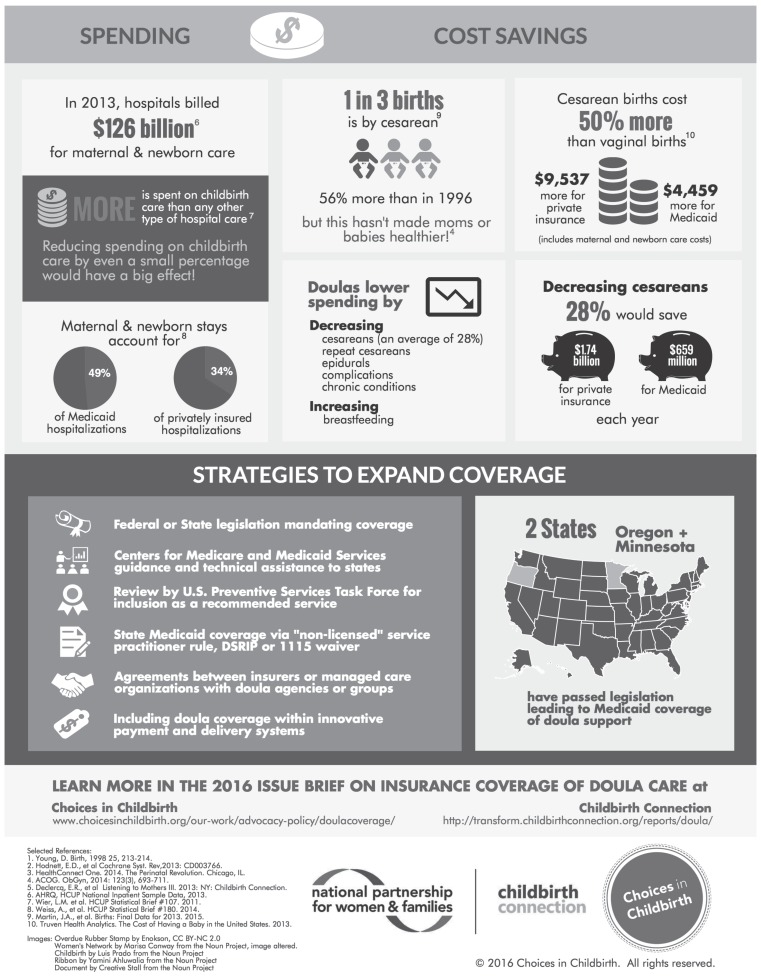

Doula care, which includes nonclinical emotional, physical, and informational support before, during, and after birth, is a proven key strategy to improve maternal and infant health. Medicaid and private insurance reimbursement for doula care would increase the availability and accessibility of this type of support and would advance the “Triple Aim” framework of the National Quality Strategy by

-

•

Improving the quality of care by making it more accessible, safe, and woman- and family-centered (e.g., by enhancing women’s experience of care and engagement in their care);

-

•

Improving health outcomes for mothers and babies; and

-

•

Reducing spending on nonbeneficial medical procedures, avoidable complications, and preventable chronic conditions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Medicaid and private insurance coverage of doula care infographic.

Rigorous studies show that doula care reduces the likelihood of such consequential and costly interventions as cesarean birth and epidural pain relief while increasing the likelihood of a shorter labor, a spontaneous vaginal birth, higher Apgar scores for babies, and a positive childbirth experience (Hodnett, Gates, Hofmeyr, & Sakala, 2013). Other smaller studies suggest that doula support is associated with increased breastfeeding (Health Connect One, 2014) and decreased postpartum depression (Wolman, Chalmers, Hofmeyr, & Nikodem, 1993). This body of research has not identified any harms of continuous labor support.

Studies in three states (Minnesota, Oregon, and Wisconsin) have concluded that Medicaid reimbursement of doula care holds the potential to achieve cost savings even when considering just a portion of the costs expected to be averted (Chapple, Gilliland, Li, Shier, & Wright, 2013; Kozhimannil, Hardeman, Attanasio, Blauer-Peterson, & O’Brien, 2013; Tillman, Gilmer, & Foster, 2012). Cesareans currently account for one of every three births, despite widespread recognition that this rate is too high. Cesareans also cost approximately 50% more than vaginal births—adding $4,459 (Medicaid payments) or $9,537 (commercial payments) to the total cost per birth in the United States in 2010 (Truven Health Analytics, 2013).

Studies in three states (Minnesota, Oregon, and Wisconsin) have concluded that Medicaid reimbursement of doula care holds the potential to achieve cost savings even when considering just a portion of the costs expected to be averted.

Because doula support increases the likelihood of vaginal birth, it lowers the cost of maternity care while improving women’s and infants’ health. Other factors associated with doula support that would contribute to cost savings include reduced use of epidural pain relief and instrument-assisted births, increased breastfeeding and a reduction in repeat cesarean births, and associated complications and chronic conditions.

Because the benefits are particularly significant for those most at risk for poor outcomes, doula support has the potential to reduce health disparities and improve health equity. Doula programs in underserved communities have had positive outcomes and are expanding, but the persistent problem of unstable funding limits their reach and impact.

In August 2013, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Expert Panel on Improving Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes in Medicaid/CHIP included providing coverage for continuous doula support during labor among its recommendations (CMS, 2013).

Currently, only two states—Minnesota and Oregon—have passed targeted legislation to obtain Medicaid reimbursement for doula support, including continuous support during labor and birth, as well as several prenatal and postpartum home visits. Implementation has been challenging, and bureaucratic hurdles make obtaining reimbursement difficult. At this time, few doulas, if any, have actually received Medicaid reimbursement in either state. Across the country, a relatively small number of doula agencies have contracted with individual Medicaid managed care organizations and other health plans to cover doula services. The extent of these untracked local arrangements is unknown.

The recently revised CMS Preventive Services Rule (42 CFR §440.130[c]) opens the door for additional state Medicaid programs to cover doula services under a new regulation, allowing reimbursement of preventive services provided by nonlicensed service providers (Mann, 2013). However, the absence of clear implementation policies or national coordination would require each state to spend considerable resources devising new processes and procedures to achieve Medicaid reimbursement for doula support.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INCREASING PUBLIC AND PRIVATE COVERAGE OF BIRTH DOULA SERVICES

-

•

Congress should designate birth doula services as a mandated Medicaid benefit for pregnant women based on evidence that doula support is a cost-effective strategy to improve birth outcomes of women and babies and reduce health disparities with no known harms.

-

•

Until this broad, optimal solution is attained, CMS should develop a clear, standardized pathway for establishing reimbursement for doula services, including prenatal and postpartum visits and continuous labor support, in all state Medicaid agencies and Medicaid managed care plans. CMS should provide guidance and technical assistance to states to facilitate this coverage.

-

•

State Medicaid agencies should take advantage of the recent revision of the Preventive Services Rule, 42 CFR §440.130(c), to amend their state plans to cover doula support. States should also include access to doula support in new and existing Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment waiver programs.

-

•

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force should determine whether continuous labor support by a trained doula falls within the scope of its work and, if so, should determine whether labor support by a trained doula meets its criteria for recommended preventive services.

-

•

Managed care organizations and other private insurance plans as well as relevant innovative payment and delivery systems with options for enhanced benefits should include support by a trained doula as a covered service.

-

•

State legislatures should pass legislation mandating private insurance coverage of doula services.

Congress should designate birth doula services as a mandated Medicaid benefit for pregnant women based on evidence that doula support is a cost-effective strategy to improve birth outcomes of women and babies and reduce health disparities with no known harms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article reproduces the Executive Summary and accompanying infographic for a longer issue brief by the same title jointly issued by Choices in Childbirth and Childbirth Connection Programs at the National Partnership for Women & Families and available at http://choicesinchildbirth.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/DoulaBrief_FINAL_1.4.16.pdf.

Biographies

NAN STRAUSS is the director of Policy and Research for Choices in Childbirth. She previously served as the director of Maternal Health Research and Policy for Amnesty International USA.

CAROL SAKALA is the director of Childbirth Connection Programs at the National Partnership for Women & Families (NPWF). She was director of Programs for Childbirth Connection from 2000 to 2014 when the organization joined forces with the NPWF. She is a co-author of the Cochrane review, “Continuous Support for Women During Childbirth.”

MAUREEN CORRY is a senior advisor for Childbirth Connection Programs at the NPWF. She was executive director of Childbirth Connection from 1995 to 2014 when the organization joined forces with the NPWF.

REFERENCES

- Caughey A. B., Cahill A. G., Guise J., & Rouse D. J. (2014). Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 210(3), 179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2013). Improving maternal and infant health outcomes: Crosswalk between current and planned CMCS activities and expert panel identified strategies. Retrieved from https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Quality-of-Care/Downloads/Crosswalk-of-Activities.pdf

- Chapple W., Gilliland A., Li D., Shier E., & Wright E. (2013). An economic model of the benefits of professional doula labor support in Wisconsin births. Wisconsin Medical Journal, 112(2), 58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Connect One. (2014). The perinatal revolution. Chicago, IL: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Hodnett E. D., Gates S., Hofmeyr G. J., & Sakala C. (2013). Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7), . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil K. B., Hardeman R. R., Attanasio L. B., Blauer-Peterson C., & O’Brien M. (2013). Doula care, birth outcomes, and costs among Medicaid beneficiaries. American Journal of Public Health, 103(4), e113–e121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann C. (2013). CMCS Informational Bulletin: Update on Preventive Services Initiatives. [Bulletin]. Baltimore, MD: Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services; Retrieved from http://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/Downloads/CIB-11-27-2013-Prevention.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Tillman T., Gilmer R., & Foster A. (2012). Utilizing doulas to improve birth outcomes for underserved women in Oregon. Portland, OR: Oregon Health Authority; Retrieved from http://www.oregon.gov/oha/legactivity/2012/hb3311report-doulas.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Truven Health Analytics. (2013). The cost of having a baby in the United States: Truven Health Analytics Market Scan Study. Ann Arbor, MI: Author; Retrieved from http://transform.childbirthconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Cost-of-Having-a-Baby1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wolman W., Chalmers B., Hofmeyr J., & Nikodem V. (1993). Postpartum depression and companionship in the clinical birth environment: A randomized, controlled study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 168(5), 1388–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]