Abstract

Enhanced control of species of Cryptococcus, non-fermentative yeast pathogens, was achieved by chemosensitization through co-application of certain compounds with a conventional antimicrobial drug. The species of Cryptococcus tested showed higher sensitivity to mitochondrial respiratory chain (MRC) inhibition compared to species of Candida. This higher sensitivity results from the inability of Cryptococcus to generate cellular energy through fermentation. To heighten disruption of cellular MRC, octyl gallate (OG) or 2,3-dihydroxybenzaldehyde (2,3-DHBA), phenolic compounds inhibiting mitochondrial functions, were selected as chemosensitizers to pyraclostrobin (PCS; an inhibitor of complex III of MRC). The cryptococci were more susceptible to the chemosensitization (i.e., PCS + OG or 2,3-DHBA) than the Candida with all Cryptococcus strains tested being sensitive to this chemosensitization. Alternatively, only few of the Candida strains showed sensitivity. OG possessed higher chemosensitizing potency than 2,3-DHBA, where the concentration of OG required with the drug to achieve chemosensitizing synergism was much lower than that required of 2,3-DHBA. Bioassays with gene deletion mutants of the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed that OG or 2,3-DHBA affect different cellular targets. These assays revealed mitochondrial superoxide dismutase or glutathione homeostasis plays a relatively greater role in fungal tolerance to 2,3-DHBA or OG, respectively. These findings show that application of chemosensitizing compounds that augment MRC debilitation is a promising strategy to antifungal control against yeast pathogens.

Keywords: chemosensitization; Cryptococcus; Candida; Saccharomyces; octyl gallate; 2,3-dihydroxybenzaldehyde; mitochondrial respiration inhibitors

1. Introduction

Mycotic infectious diseases, such as candidiasis or cryptococcosis caused by various species of Candida or Cryptococcus, respectively, are continuously expanding as serious global health issues. This expansion is mainly associated with immunocompromised disorders (e.g., AIDS, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, etc.) [1] and concomitant development of resistance to antifungal drugs [2]. Consequently, there is persistent need to enhance the effectiveness of conventional antimycotic drugs or discover and develop new ones [3].

Mitochondrial functions of fungi have been examined as potential targets for antifungal therapy ([4] for review). For example, certain mitochondrial mutants exhibited increased susceptibility to polyene or azole drugs, possibly resulting from changes in sterol levels of membranes ([4] and references therein). In particular, the mitochondrial respiratory chain (MRC; See Figure 1 for the structure of MRC) is a target of the MRC-inhibitory drug atovaquone (ATQ; hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone) for control of the infections of fungi, such as Pneumocystis jirovecii (pneumonia) [5]. Such MRC-inhibitory drugs disrupt production of cellular energy (ATP) in fungal cells. Of note, ATQ is also used to treat malarial parasites, such as Plasmodium, where ATQ not only inhibits the MRC, but also disrupts the inner mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) [6].

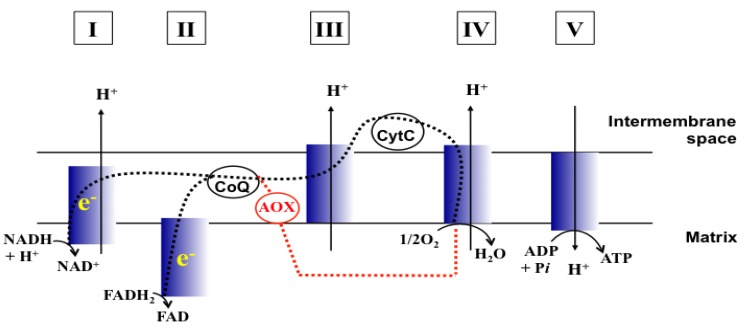

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of MRC (Adapted from [17] and [18]). CoQ, Coenzyme Q; CytC, Cytochrome C; e−, Electrons; Dashed line (black), Electron flow w/o MRC inhibition; Dashed line (red), Electron flow through AOX when MRC is inhibited. I to V, complexes I to V of MRC.

MRC inhibitors can also trigger oxidative stress resulting from leakage of electrons from the MRC, resulting in oxidative damage to cellular components, such as cell membranes/lipid bilayers. This demonstrates that the fungal antioxidant system (superoxide dismutases, glutathione reductase, stress signaling pathway, etc.) plays a crucial role in maintaining cellular integrity from toxic reactive oxygen species [7,8]. To date, while the MRC has been targeted for control of agro-fungal pathogens, it has been a relatively unexploited drug target against clinical fungal pathogens.

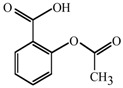

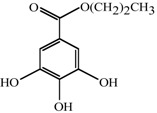

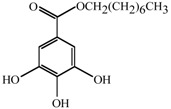

Antifungal MRC targeting could possibly be enhanced by compounds affecting cellular redox homeostasis. Natural phenolic compounds or their structural derivatives, which are redox-active, can serve as potent redox cyclers against fungal pathogens, resulting in inhibition of microbial growth ([9] and references therein). This inhibition results from destabilization of cellular redox homeostasis, antioxidant systems or the function of redox-sensitive components [10,11]. Meanwhile, certain phenolic compounds/derivatives can also inhibit various functions of mitochondrial components (See Table 1). For example, gallate derivatives, such as propyl- or octyl gallate (PG or OG, respectively), inhibit the activity of cellular alternative oxidase (AOX). AOX functions in fungi to overcome the toxicity triggered by MRC inhibitors, rendering the completion of electron transfer via MRC ([12,13]; See Figure 1). OG further disrupts and/or disorganizes the lipid bilayer-protein interface in fungal cells [14]. Likewise, acetylsalicylic acid (AcSA) or 2,3-dihydroxybenzaldehyde (2,3-DHBA) also inhibits the functions of mitochondria or mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD), respectively, in fungi [15,16].

Table 1.

Mitochondrial targets and structures of compounds tested in this study.

| Compounds | Target | References |

|---|---|---|

| 2,3-DHBA | Mn-SOD ( Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mn-SOD gene deletion mutant is hypersensitive to 2,3-DHBA) | [ 15] |

| ||

| AcSA | General mitochondrial function ( Aspergillus fumigatus sakAΔ [oxidative stress-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinase gene deletion mutant] was also hypersensitive to AcSA [See [26]].) | [ 16] |

| ||

| PG | AOX | [ 13,27] |

| ||

| OG | AOX | [ 28,29] |

|

Chemosensitization is a strategy where co-application of certain types of compounds along with a conventional antimicrobial drug increases the effectiveness of the drug [19,20,21,22]. Examples include: (1) 4-methoxy-2,3,6-trimethylbenzensulfonyl-substituted d-octapeptide, which sensitizes pathogenic Candida strains to fluconazole (FLC), resulting in countering FLC resistance of clinical isolates [22], (2) 7-chlorotetrazolo[5,1-c]benzo[1,2,4]triazine (CTBT), which increases the susceptibility of Candida and Saccharomyces strains to cycloheximide, 5-fluorocytosine and azole drugs [23], (3) squalamine (a modifier of membrane integrity by increasing permeability of drugs), which enhances the susceptibility of various antibiotic-resistant and susceptible strains of Gram-negative bacteria to drugs [21], and (4) antimycin A (AntA) and benzhydroxamic acid (BHAM), which makes Rhizopus oryzae hypersensitive to triazoles, i.e., posaconazole (PCZ) and itraconazole (ICZ), via apoptosis [24]. Collectively, these studies showed that antimicrobial drug therapy that includes chemosensitization could lead to lowering dosage levels of conventional drugs needed for control of pathogens, in both drug-resistant and susceptible strains.

Various species of Cryptococcus and Candida are human and animal pathogens. For example, cryptococcal meningitis is reported to be the leading cause of death among those infected with HIV [25]. However, one of the key differences between the yeasts in these two genera is that species of Cryptococcus are non-fermentative, while the Candida species are fermentative [16].

Based on this difference, we reasoned the following: (1) When cellular MRC is disrupted by MRC-inhibitory drug(s), the Cryptococcus would show higher sensitivity than the Candida, (2) This higher sensitivity is due to the fact that the Candida can generate cellular energy also through fermentation (other than MRC), while the Cryptococcus, being non-fermentative, lack this ability, and (3) Thus, MRC could serve as an effective antifungal target especially for control of Cryptococcus pathogens.

In this study, we investigated if selected phenolic compounds/derivatives (See Table 1) could enhance the antifungal potency of pyraclostrobin (PCS), the most potent complex III inhibitor of MRC in our test, against Cryptococcus. Our hypothesis was that co-application of phenolic compounds/derivatives (as chemosensitizers) and PCS will negatively affect the common cellular target, i.e., functions of mitochondria, resulting in increased sensitivity of fungi. We also evaluated the potential of these chemosensitizing compounds to serve as active pharmaceutical “leads” against Cryptococcus yeasts, and compared the effectiveness of chemosensitization between Cryptococcus and Candida (See Table 2 for strains tested). Our results showed that the Cryptococcus were more susceptible to OG- or 2,3-DHBA-mediated chemosensitization to PCS than the Candida, where the chemosensitizing capacity of OG was found to be greater than that of 2,3-DHBA.

Table 2.

Yeast strains used in this study.

| Yeast strains | Strain characteristics | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Cryptococcus | ||

| C. neoformans 90112 | Clinical reference strain | ATCC a |

| C. neoformans 208821 | Clinical isolate | ATCC |

| C. neoformans MYA-4564 | Clinical reference strain | ATCC |

| C. neoformans MYA-4565 | Clinical reference strain | ATCC |

| C. neoformans MYA-4566 | Clinical reference strain | ATCC |

| C. neoformans MYA-4567 | Clinical reference strain | ATCC |

| C. neoformans CN24 | Clinical isolate | IHMT b |

| C. gatti MYA-4560 | Clinical reference strain | ATCC |

| C. gatti MYA-4561 | Clinical reference strain | ATCC |

| Candida | ||

| C. albicans 90028 | Clinical reference strain | ATCC |

| C. albicans CAN242 | Clinical isolate | IHMT |

| C. albicans CAN276 | Clinical isolate | IHMT |

| C. glabrata 90030 | Clinical reference strain | ATCC |

| C. glabrata 2001 | Clinical reference strain | ATCC |

| C. glabrata CAN252 | Clinical isolate | IHMT |

| C. krusei 6258 | Clinical reference strain | ATCC |

| C. krusei CAN82 | Clinical isolate | IHMT |

| C. krusei CAN75 | Clinical isolate | IHMT |

| Saccharomyces | ||

| S. cerevisiae BY4741 | Model yeast, Parental strain (Mat a his3∆1 leu2∆0 met15∆0 ura3∆0) |

SGD c |

| S. cerevisiae sod2∆ | Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD) mutant derived from BY4741 | SGD |

| S. cerevisiae yap1∆ | Transcription factor YAP1 mutant derived from BY4741 | SGD |

| S. cerevisiae trr1∆ | Cytosolic thioredoxin reductase mutant derived from BY4741 | SGD |

| S. cerevisiae trr2∆S. cerevisiae tsa1∆ | Mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase mutant derived from BY4741Thiredoxin peroxidase mutant derived from BY4741 | SGD

SGD |

a.ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA; b.IHMT, Instituto de Higiene e Medicina Tropical/CREM, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal; c.SGD, Saccharomyces Genome Database [30].

2. Results and Discussion

We initially tested the effect of chemosensitization by co-applying commercial antifungal/antimalarial drugs “ATQ + proguanil” on the growth of fermenting and non-fermenting yeast pathogens. For this test, we chose representative yeast pathogens, i.e., C. albicans 90028 as a fermentor, and C. neoformans 90112 and C. gatti 4560 as non-fermentors. In protozoan parasites, co-application of proguanil (a mitochondria-modulating chemosensitizer) increased anti-parasitic activity of ATQ [31]. Noteworthy is that proguanil-mediated chemosensitization was specific for ATQ. Proguanil did not increase the potency of other types of MRC inhibitors (e.g., myxothiazole, AntA) [31]. Thus, these results with malarial parasites (Plasmodium) indicated “drug-chemosensitizer specificity” existed during the chemosensitization process.

We used the checkerboard microdilution bioassay protocol outlined by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [32], with various concentrations of ATQ (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 μg/mL) and proguanil (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 μg/mL). Our results showed that: (1) Independent application of ATQ or proguanil, alone, did not exhibit discernable growth inhibition in any of the test yeast strains, even at the highest concentration (i.e., 16 μg/mL), and also (2) Co-application of ATQ with proguanil did not enhance the antifungal activity of either compounds, indicating no chemosensitization occurred by “ATQ + proguanil” co-treatment in these strains (Data not shown).

In the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, nine cellular transporters required for sequestering toxic drugs/compounds out of the cell need to be knocked out to exhibit ATQ sensitivity [33]. This indicates active drug-detoxification systems do operate in S. cerevisiae. We surmised that pathogenic yeasts, i.e., Cryptococcus or Candida, might also operate similar type(s) of detoxification system(s), enabling these pathogens to escape from ATQ/proguanil-triggered toxicity. Therefore, we performed chemosensitization tests using other types of MRC inhibitors with co-application of phenolic compounds (i.e., OG, PG, 2,3-DHBA, AcSA; See Table 1) as chemosensitizers.

2.1. PCS Is the Most Potent MRC Inhibitor in Cryptococcus

First, we identified the potency of MRC inhibitors tested against yeast pathogens. Antifungal efficacy was compared among 12 different MRC inhibitors disrupting one of the five different components of MRC, i.e., complexes I to IV or AOX (See Table 3, Figure 1). The level of differential sensitivity between fermenting (Candida) and non-fermenting (Cryptococcus) yeasts to the MRC inhibitors was determined by an agar plate-based yeast dilution bioassay (See Experimental section). We initially examined (1) three fermentors: C. albicans 90028, C. glabrata 90030, C. krusei 6258 and (2) two non-fermentors: C. neoformans 90112, C. gatti MYA-4560.

Table 3.

Summary of levels of growth inhibition of representative yeast pathogens by MRC inhibitors: agar plate-based yeast dilution bioassays. a

| MRC components targeted |

MRC inhibitors applied |

C. neoformans 90112 |

C. gatti MYA-4560 |

C. albicans 90028 |

C. glabrata 90030 |

C. krusei 6258 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| I | Rotenone | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| II | Carboxin | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| TTFA | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| 3-NPA | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| AOX | BHAM | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| SHAM | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| III | AntA | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Kre-Me | 3 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| PCS | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| AZS | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| IV | KCN | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Na-azide | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

a.TTFA, Thenoyltrifluoroacetone; 3-NPA, 3-Nitropropionic acid; BHAM, Benzhydroxamic acid; SHAM, Salicylhydroxamic acid; AntA, Antimycin A; Kre-Me, Kresoxim methyl; PCS, Pyraclostrobin; AZS, Azoxystrobin; KCN, Potassium cyanide; Na-azide, Sodium azide. Numbers represented highest dilution level (log10) where cell growth was visible. Numbers in bold show cell growth was inhibited (viz., < 6).

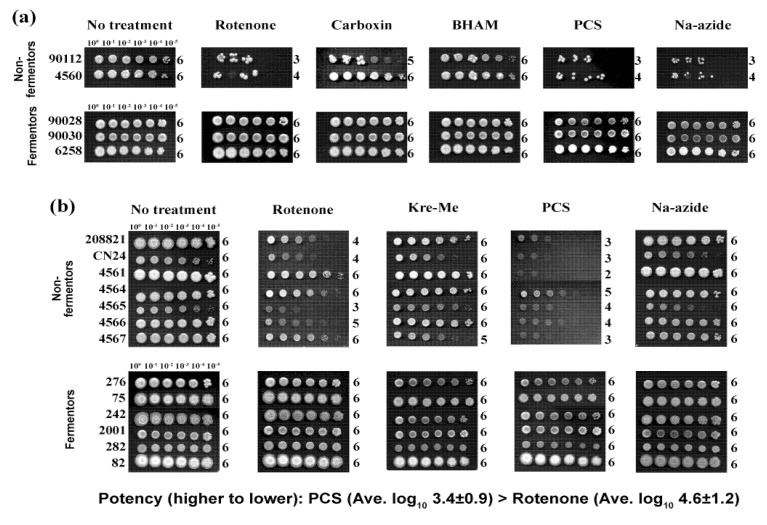

MRC inhibitors targeting complex I, III or IV reduced the growth of the Cryptococcus, with differing levels of fungal sensitivity (Table 3, Figure 2a). For example, when C. neoformans 90112 was treated with complex III inhibitors, growth was inhibited by 100 to 1000 times more compared to controls (i.e., log10 dilution score of “no treatment” controls was “6” [i.e., yeast cells appeared at the highest dilution level of 106] vs. log10 score of “treatments” was “3–4” [i.e., cells did not appear at dilution levels greater than103–104]), depending on types of complex III inhibitors applied. Also, rotenone (a complex I inhibitor) and Na-azide (a complex IV inhibitor) inhibited the growth of C. neoformans 90112 at cell dilution levels above 103 times.

Figure 2.

Differential antifungal activity of MRC inhibitors, targeting complexes I - IV or AOX, in yeast pathogens. (a) Representative yeast dilution bioassay showing Cryptococcus strains, non-fermentors, are relatively more sensitive to MRC inhibitors (rotenone, carboxin, PCS, Na-azide) than Candida strains, fermentors. 100 to 10−5, yeast-cell dilution level; Numbers on the right side of each row (0 to 6), log10 score of cell numbers visible (survived) (See Experimental section and Table 3). (b) Yeast dilution bioassay showing PCS is the most potent MRC inhibitor tested, followed by rotenone (Cell dilution level showing visible growth equates to antifungal potency [higher dilution score with visible growth = lower potency]; PCS, average log10 score = 3.4 ± 0.9 vs. rotenone, average log10 score = 4.6 ± 1.2. Average log10 score was determined in nine Cryptococcus strains). As observed in panel (a), Candida strains did not exhibit growth inhibition to any of the MRC inhibitors tested.

Growth of C. gatti 4560 was also decreased by four different MRC inhibitors (Table 3). However, unlike the results of C. neoformans 90112, AntA and AZS did not inhibit the growth of C. gatti 4560 (Table 3). Moreover, besides carboxin, which inhibited C. neoformans 90112, both complex II and AOX inhibitors did not discernably inhibit the growth of C. neoformans 90112 or C. gatti 4560 (See also Figure 2a).

Based on these initial bioassays, rotenone, Kre-Me, PCS and Na-azide (exhibiting antifungal activity against both C. neoformans 90112 and C. gatti 4560) were selected for further evaluation for antifungal potency against additional test strains (i.e., seven additional Cryptococcus and six additional Candida strains) (See Figure 2b). A similar trend of growth inhibition was found in these additional Cryptococcus strains with PCS and rotenone, while Kre-Me and Na-azide showed almost no effect. The growth of the additional Candida strains was not noticeably affected by any of these same treatments. In summary: (1) PCS possessed the highest antifungal activity (Average log10 dilution score = 3.4 ± 0.9, this lowest average log10 score was based upon the results using nine Cryptococcus strains shown in Figure 2a,b), followed by rotenone (average log10 score = 4.6 ± 1.2); (2) as expected, the growth of the Candida (fermenting yeasts) was not affected by any of the MRC inhibitors tested (Table 3; Figure 2a,b), and (3) thus, we chose PCS as the most potent MRC-inhibitory drug against Cryptococcus in our chemosensitization study.

2.2. Antifungal Chemosensitization Tests in Yeast Pathogens

2.2.1. Selection of OG and 2,3-DHBA as the Most Potent Chemosensitizers

Next, we identified the most potent antifungal chemosensitizer(s), among four phenolic compounds listed in Table 1, which inhibit functions of fungal mitochondria. Based on agar plate-based yeast dilution bioassay (See Experimental section), we determined minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of OG, PG, 2,3-DHBA and AcSA. As shown in Table 4, OG and 2,3-DHBA possessed the highest antifungal activity (i.e., low MIC values) compared to PG or AcSA. Of note, Candida strains were generally more tolerant to the phenolic compounds tested compared to Cryptococcus strains. Based on these results, OG and 2,3-DHBA were selected as the chemosensitizers to test with PCS.

Table 4.

MIC (mM) of four phenolic compounds tested in this study: agar plate-based yeast dilution bioassays a.

| Strains | OG | PG | 2,3-DHBA | AcSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. neoformans 90112 | 0.1 | > 10 | 0.2 | 7 |

| C. gatti 4560 | 0.1 | > 10 | 0.3 | 7 |

| C. albicans 90028 | 0.3 | > 10 | 1.0 | > 10 |

| C. glabrata 90030 | 0.2 | > 10 | 2.0 | > 10 |

| C. krusei 6258 | 0.3 | > 10 | 2.0 | > 10 |

| Average | 0.2 ± 0.1 | > 10 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | > 8.8 ± 1.6 |

a MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration, where no yeast growth was observed in any dilution spots on the agar plate.

2.2.2. Chemosensitization in Cryptococcus: 2,3-DHBA + PCS

Antifungal chemosensitization was tested based on the EUCAST checkerboard microdilution bioassay protocol [32] (concentrations of compound examined were listed in Experimental section). For MICs, “synergistic” Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Indices (FICIs; see Experimental section for calculations) (i.e., FICI ≤ 0.5) were found between 2,3-DHBA and PCS for most Cryptococcus strains (Table 5). Despite the absence of calculated synergism, as determined by “indifferent” interactions [34] (Table 5), there was increased antifungal activity of 2,3-DHBA and PCS (i.e., chemosensitization; FICI = 0.8) in C. neoformans 4567, which was reflected in lowered MICs of 2,3-DHBA or PCS when combined. However, for Minimum Fungicidal Concentrations (MFCs), “synergistic” Fractional Fungicidal Concentration Indices (FFCIs) (at the level of ≥ 99.9% fungal death) between 2,3-DHBA and PCS occurred only in C. neoformans strains 4565 and CN24 (Table 5). Therefore, results indicated that the 2,3-DHBA-mediated chemosensitization with PCS is fungistatic, not fungicidal (i.e., Mean MFCcombined for 2,3-DHBA or PCS/ Mean MICcombined for 2,3-DHBA or PCS was > 4 [See [35] for reference]), in most Cryptococcus strains tested.

Table 5.

Antifungal chemosensitization of 2,3-DHBA (mM) to PCS (μg/mL) tested against Cryptococcus strains: EUCAST-based microdilution bioassays. a

| Strains | Compounds | MIC | MIC | FICI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alone | combined | |||

| C. neoformans 90112 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.5 |

| PCS | 4 | 1 | ||

| C. neoformans 208821 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.3 |

| PCS | >16 b | 2 | ||

| C. neoformans 4564 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.5 |

| PCS | >16 | 8 | ||

| C. neoformans 4565 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.5 |

| PCS | >16 | 1 | ||

| C. neoformans 4566 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.3 |

| PCS | >16 | 2 | ||

| C. neoformans 4567 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.8 |

| PCS | 4 | 2 | ||

| C. neoformans CN24 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.5 |

| PCS | 16 | 0.25 | ||

| C. gatti 4560 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.5 |

| PCS | 8 | 0.25 | ||

| C. gatti 4561 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.5 |

| PCS | 4 | 1 | ||

| Mean | 2,3-DHBAPCS | 0.218.2 | 0.051.9 | 0.4 |

| t-test c | 2,3-DHBA | - | p < 0.005 | - |

| PCS | - | p < 0.005 | - | |

| C. neoformans 90112 | 2,3-DHBA | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| PCS | >16 | 2 | ||

| C. neoformans 208821 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.8 | 0.8 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. neoformans 4564 | 2,3-DHBA | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| PCS | >16 | 4 | ||

| C. neoformans 4565 | 2,3-DHBA | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| PCS | >16 | 8 | ||

| C. neoformans 4566 | 2,3-DHBA | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| PCS | >16 | 8 | ||

| C. neoformans 4567 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.8 | 0.8 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. neoformans CN24 | 2,3-DHBA | 3.2 | 1.6 | 0.5 |

| PCS | >16 | 0.25 | ||

| C. gatti 4560 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| PCS | >16 | 16 | ||

| C. gatti 4561 | 2,3-DHBA | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| PCS | >16 | 2 | ||

| Mean | 2,3-DHBA | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| PCS | 32.0 | 11.6 | ||

| t-test | 2,3-DHBA | - | p < 0.05 | - |

| PCS | - | p < 0.005 | - |

a Synergistic FICIs and FFCIs are indicated in bold; b PCS was tested up to 16 μg/mL. For calculation purposes, 32 μg/mL (doubling of 16 μg/mL) was used; c Student’s t-test for paired data, mean MIC or MFC of each compound (combined, i.e., chemosensitization) vs. mean MIC or MFC of each compound (alone, i.e., no chemosensitization), was determined in nine strains (Calculation was based on [36]).

2.2.3. Chemosensitization in Candida: 2,3-DHBA + PCS

The effect of “2,3-DHBA + PCS” chemosensitization was also examined in the Candida where “no synergistic” FICIs were found. However, there was increased antifungal activity with 2,3-DHBA + PCS (i.e., chemosensitization) in five strains (i.e., all three C. krusei strains, C. albicans CAN242 and C. glabrata CAN252), as reflected in lower MICs of each compound when co-applied (Table 6) than when applied alone. However, FICIs for the remaining four Candida strains and FFCIs for all Candida were 2.0 (i.e., no compound interactions occurred at all), indicating these fermenting yeast strains were relatively tolerant to any chemosensitization exerted by “2,3-DHBA + PCS.”

Table 6.

Antifungal chemosensitization of 2,3-DHBA (mM) to PCS (μg/mL) tested against Candida: EUCAST-based microdilution bioassays.

| Strains | Compounds | MIC | MIC | FICI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alone | combined | |||

| C. albicans 90028 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.2 | 0.2 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 a | >16 | ||

| C. albicans CAN242 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| PCS | >16 | 2 | ||

| C. albicans CAN276 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.2 | 0.2 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. glabrata 90030 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.2 | 0.2 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. glabrata 2001 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.2 | 0.2 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. glabrata CAN252 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| PCS | >16 | 2 | ||

| C. krusei 6258 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| PCS | >16 | 2 | ||

| C. krusei CAN82 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| PCS | >16 | 2 | ||

| C. krusei CAN75 | 2,3-DHBA | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| PCS | >16 | 2 | ||

| Mean | 2,3-DHBA | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| PCS | 32.0 | 15.3 | ||

| t-test b | 2,3-DHBA | - | p < 0.01 | - |

| PCS | - | p < 0.01 | - | |

| C. albicans 90028 | 2,3-DHBA | 6.4 | 6.4 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. albicans CAN242 | 2,3-DHBA | 3.2 | 3.2 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. albicans CAN276 | 2,3-DHBA | >6.4 | >6.4 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. glabrata 90030 | 2,3-DHBA | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. glabrata 2001 | 2,3-DHBA | 3.2 | 3.2 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. glabrata CAN252 | 2,3-DHBA | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. krusei 6258 | 2,3-DHBA | 6.4 | 6.4 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. krusei CAN82 | 2,3-DHBA | >6.4 | >6.4 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. krusei CAN75 | 2,3-DHBA | >6.4 | >6.4 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| Mean | 2,3-DHBA | 6.8 | 6.8 | 2.0 |

| PCS | 32.0 | 32.0 | ||

| t-test | 2,3-DHBA | - | p = 1.0 | - |

| PCS | - | N/D c | - |

a PCS was tested up to 16 μg/mL. For calculation purposes, 32 μg/mL (doubling of 16 μg/mL) was used. b Student’s t-test for paired data, mean MIC or MFC of each compound (combined, i.e., chemosensitization) vs. mean MIC or MFC of each compound (alone, i.e., no chemosensitization), was determined in nine strains (Calculation was based on [36]). c N/D, not determined (all > 16 μg/mL).

2.2.4. Chemosensitization in Cryptococcus: OG + PCS

Next, chemosensitization efficacy of “OG + PCS” in Cryptococcus was evaluated. For MICs, synergistic FICIs were achieved for most of the Cryptococcus strains (Table 7). Similar to the results for “2,3-DHBA + PCS”, the only exception for achieving synergism was C. neoformans 4567, which was determined to be an “indifferent” interaction. However, increased antifungal activity of OG and PCS (i.e., chemosensitization; FICI = 0.6) could be achieved in C. neoformans 4567, resulting in lowered MICs of OG or PCS when co-applied.

Table 7.

Antifungal chemosensitization of OG (mM) to PCS (μg/mL) tested against Cryptococcus strains: EUCAST-based microdilution bioassays. a

| Strains | Compounds | MIC | MIC | FICI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alone | combined | ||||

| C. neoformans 90112 | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.4 | |

| PCS | 4 | 0.5 | |||

| C. neoformans 208821 | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.3 | |

| PCS | >16 b | 0.5 | |||

| C. neoformans 4564 | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.4 | |

| PCS | >16 | 4 | |||

| C. neoformans 4565 | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.3 | |

| PCS | >16 | 0.5 | |||

| C. neoformans 4566 | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.3 | |

| PCS | >16 | 1 | |||

| C. neoformans 4567 | OG | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.6 | |

| PCS | 4 | 0.25 | |||

| C. neoformans CN24 | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.5 | |

| PCS | 16 | 4 | |||

| C. gatti 4560 | OG | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.5 | |

| PCS | 8 | 0.25 | |||

| C. gatti 4561 | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.4 | |

| PCS | 4 | 0.5 | |||

| Mean | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.3 | |

| PCS | 18.2 | 1.3 | |||

| t-test c | OG | - | p < 0.005 | - | |

| PCS | - | p < 0.005 | - | ||

| C. neoformans 90112 | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.4 | |

| PCS | >16 | 4 | |||

| C. neoformans 208821 | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.3 | |

| PCS | >16 | 2 | |||

| C. neoformans 4564 | OG | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.5 | |

| PCS | >16 | 0.25 | |||

| C. neoformans 4565 | OG | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.5 | |

| PCS | >16 | 0.25 | |||

| C. neoformans 4566 | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.5 | |

| PCS | >16 | 8 | |||

| C. neoformans 4567 | OG | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.5 | |

| PCS | >16 | 0.25 | |||

| C. neoformans CN24 | OG | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.4 | |

| PCS | >16 | 4 | |||

| C. gatti 4560 | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.3 | |

| PCS | >16 | 0.5 | |||

| C. gatti 4561 | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.4 | |

| PCS | >16 | 4 | |||

| Mean | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.3 | |

| PCS | 32.0 | 2.6 | |||

| t-test | OG | - | p < 0.005 | - | |

| PCS | - | p < 0.005 | - | ||

a Synergistic FICIs and FFCIs are indicated in bold; b PCS was tested up to 16 μg/mL. For calculation purposes, 32 μg/mL (doubling of 16 μg/mL) was used; c Student’s t-test for paired data, mean MIC or MFC of each compound (combined, i.e., chemosensitization) vs. mean MIC or MFC of each compound (alone, i.e., no chemosensitization), was determined in nine strains (Calculation was based on [36]).

For MFCs, synergistic FFCIs (at the level of ≥ 99.9% fungal death) between OG and PCS occurred in all Cryptococcus strains (Table 7), reflecting the most potent antifungal activity of OG, as determined in Table 4. Most notable is that the concentration of OG needed to achieve synergism with PCS was much lower than that for 2,3-DHBA, i.e., chemosensitizing potency (higher to lower, as indicated by lower concentrations required) = OG (0.01–0.02 mM) > 2,3-DHBA (0.2–1.6 mM; See also Table 5).

2.2.5. Chemosensitization in Candida: OG + PCS

The chemosensitization effect of “OG + PCS” was further examined in the Candida strains. For MICs, “synergistic” FICIs were found in four strains, i.e., all three C. krusei strains and C. glabrata CAN252 (Table 8). This synergism was not detected with “2,3-DHBA + PCS”, further reflecting the higher antifungal activity of OG than 2,3-DHBA (See also Table 6). Despite the “indifferent” interaction, increased antifungal activity of OG and PCS (i.e., chemosensitization; FICI = 0.6) occurred in C. albicans CAN242, as determined in lowered MICs of OG or PCS when combined (Table 8).

Table 8.

Antifungal chemosensitization of OG (mM) to PCS (μg/mL) tested against Candida strains: EUCAST-based microdilution bioassays. a

| Strains | Compounds | MIC | MIC | FICI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alone | combined | |||

| C. albicans 90028 | OG | 0.08 | 0.08 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 b | >16 | ||

| C. albicans CAN242 | OG | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.6 |

| PCS | >16 | 2 | ||

| C. albicans CAN276 | OG | 0.08 | 0.08 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. glabrata 90030 | OG | 0.04 | 0.04 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. glabrata 2001 | OG | 0.04 | 0.04 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. glabrata CAN252 | OG | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.3 |

| PCS | >16 | 2 | ||

| C. krusei 6258 | OG | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.5 |

| PCS | >16 | 0.25 | ||

| C. krusei CAN82 | OG | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.5 |

| PCS | >16 | 0.25 | ||

| C. krusei CAN75 | OG | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.5 |

| PCS | >16 | 0.5 | ||

| Mean | OG | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.2 |

| PCS | 32.0 | 14.8 | ||

| t-test c | OG | - | p < 0.05 | - |

| PCS | - | p < 0.01 | - | |

| C. albicans 90028 | OG | 0.08 | 0.08 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. albicans CAN242 | OG | 0.08 | 0.08 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. albicans CAN276 | OG | 0.08 | 0.08 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. glabrata 90030 | OG | 0.08 | 0.08 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. glabrata 2001 | OG | 0.08 | 0.08 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| C. glabrata CAN252 | OG | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.5 |

| PCS | >16 | 1 | ||

| C. krusei 6258 | OG | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.6 |

| PCS | >16 | 4 | ||

| C. krusei CAN82 | OG | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.5 |

| PCS | >16 | 0.25 | ||

| C. krusei CAN75 | OG | 0.16 | 0.16 | 2.0 |

| PCS | >16 | >16 | ||

| Mean | OG | 0.1 | 0.08 | 1.5 |

| PCS | 32.0 | 21.9 | ||

| t-test | OG | - | p < 0.5 | - |

| PCS | - | p < 0.1 | - |

a Synergistic FICIs and FFCI are indicated in bold. b PCS was tested up to 16 μg/mL. For calculation purposes, 32 μg/mL (doubling of 16 μg/mL) was used. c Student’s t-test for paired data, mean MIC or MFC of each compound (combined, i.e., chemosensitization) vs. mean MIC or MFC of each compound (alone, i.e., no chemosensitization), was determined in nine strains (Calculation was based on [36]).

Of note, the trends of compound interactions of OG + PCS for MICs in Table 8 were congruent with “2,3-DHBA + PCS” chemosensitization (Table 6). For both “2,3-DHBA + PCS” and “OG + PCS”, incremental increase of growth inhibition occurred in five common strains, i.e., all three C. krusei strains, C. albicans CAN242 and C. glabrata CAN252 (Table 6, Table 8). This indicated that strain specificity to chemosensitization also exists. This is reflected in the level of differential vulnerability of each strain to chemosensitization (See also FICIs of C. neoformans 4567 in Table 5, Table 7, showing lower sensitivity of this strain to both OG- and 2,3-DHBA-mediated chemosensitization compared to other Cryptococcus strains).

For MFCs, synergistic FFCIs (at the level of ≥99.9% fungal death) between OG and PCS were achieved in C. krusei CAN82 and C. glabrata CAN252. While the FFCI of C. krusei 6258 was scored as “indifferent”, there was increased antifungal activity of OG and PCS (i.e., chemosensitization; FFCI = 0.6) with this strain. FFCIs for the remaining strains were “indifferent”, and as observed in “2,3-DHBA + PCS” assays, Candida strains were more tolerant to “OG + PCS” chemosensitization compared to Cryptococcus strains.

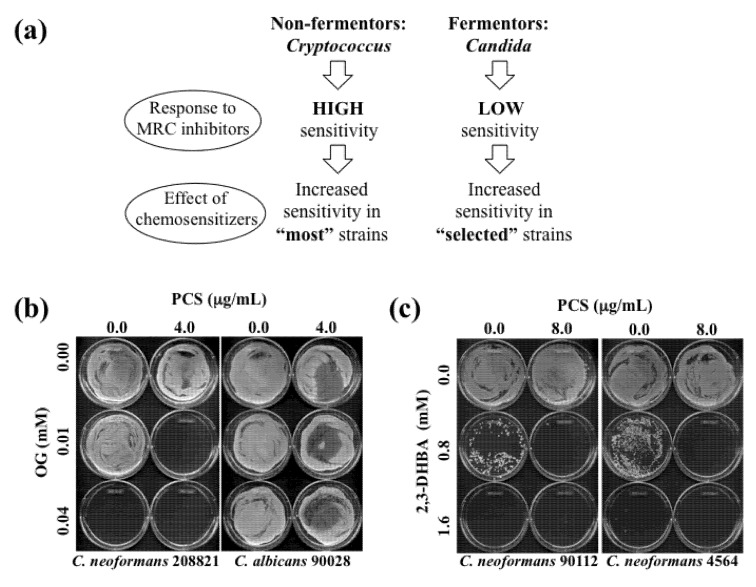

The results of all chemosensitization tests (i.e., PCS + 2,3-DHBA or OG in both Cryptococcus and Candida strains) are summarized in Table 9. Exemplary MFC test results, based on chemosensitization (PCS + OG or 2,3-DHBA) performed in Cryptococcus or Candida strains, are provided in Figure 3.

Table 9.

SUMMARY: Antifungal chemosensitization of OG or 2,3-DHBA (mM) to PCS (μg/mL) tested against Cryptococcus or Candida strains determined by EUCAST-based microdilution bioassays. Data shown are mean values derived from Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8. a

| Compounds | MIC | MIC | FICI | MFC | MFC | FFCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alone | combined | alone | combined | ||||

| Cryptococcus | OG | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.3 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.3 |

| PCS | 18.2 | 1.3 | 32.0 | 2.6 | |||

| Candida | OG | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 1.5 |

| PCS | 32.0 | 14.8 | 32.0 | 21.9 | |||

| Cryptococcus | 2,3-DHBA | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| PCS | 18.2 | 1.9 | 32.0 | 11.6 | |||

| Candida | 2,3-DHBA | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 2.0 |

| PCS | 32.0 | 15.3 | 32.0 | 32.0 |

a Synergistic FICIs and FFCI are indicated in bold.

Figure 3.

(a) Diagram describing effects of OG- or 2,3-DHBA-mediated chemosensitization to PCS in “most” Cryptococcus strains (non-fermentors) or in “selected (e.g., five sensitive strains described in Table 6, Table 8)” Candida strains (fermentors). (b) Representative MFC test results performed in C. neoformans 208821 and C. albicans 90028 after chemosensitization (PCS + OG). Results showed that C. neoformans 208821 (non-fermentor) was more sensitive (i.e., “no growth” with PCS4.0 μg/mL + OG0.01 mM) to the chemosensitization than C. albicans 90028 (fermentor) (i.e., “growth” with PCS4.0 μg/mL + OG0.01 mM). (c) Representative MFC test results performed in C. neoformans 90112 and 4564 after chemosensitization (PCS + 2,3-DHBA).

2.2.6. Differential Responses of S. cerevisiae Antioxidant Mutants to OG or 2,3-DHBA

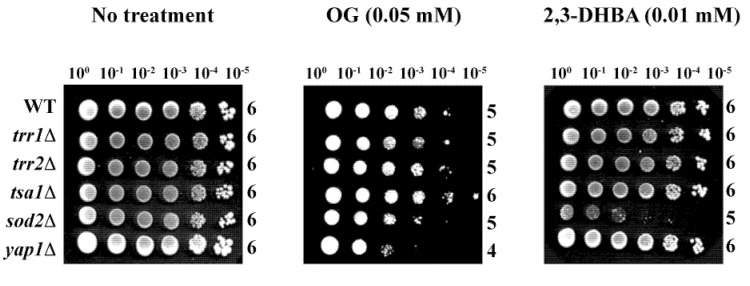

Identification of fungal target(s) of OG or 2,3-DHBA within the antioxidant system was attempted using gene deletion mutants of the model yeast, S. cerevisiae. Agar plate-based yeast dilution bioassays on SG with OG or 2,3-DHBA (See Experimental section for test concentrations), in duplicate, included the wild type (WT) and five antioxidant mutant strains, as follows: (1) yap1Δ (Yap1p is the transcription factor regulating expression of four downstream genes within the oxidative stress response pathway, i.e., GLR1 [glutathione reductase], YCF1 [a glutathione S-conjugate pump], GSH1 [γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase, which catalyzes the first step in glutathione biosynthesis] and TRX2 [thioredoxin] [37,38]), (2) sod2Δ (mitochondrial superoxide dismutase, Mn-SOD), (3) trr1Δ (cytoplasmic thioredoxin reductase), (4) trr2Δ (mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase), and (5) tsa1Δ (thioredoxin peroxidase) (See Saccharomyces Genome Database [30]).

Of the five deletion mutants, yap1Δ was hypersensitive to OG (log10 = 4), while sod2Δ was hypersensitive to 2,3-DHBA (log10 = 5) (Figure 4) (see also [15]). These results indicate OG or 2,3-DHBA affect different cellular components in fungi, where Mn-SOD plays a relatively greater role in fungal tolerance to 2,3-DHBA, while glutathione homeostasis, etc., protects cells from OG-induced toxicity, compared to the other genes represented. Further studies, such as microarray-based chemogenomic analysis, inclusion of more gene deletion mutants, etc., are warranted to determine the precise mechanism of action of OG or 2,3-DHBA during chemosensitization.

Figure 4.

Agar plate-based yeast dilution bioassay identifying sensitive mutants of S. cerevisiae to phenolic chemosensitizers (100 to 10−5: yeast dilution rates). Results showed the sensitive responses of yap1Δ to OG and sod2Δ to 2,3-DHBA, respectively.

3. Experimental

3.1. Yeast Strains

Yeast strains (Cryptococcus-C. neoformans, C. gatti; Candida- C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei; Saccharomyces cerevisiae; See Table 2) were cultured on synthetic glucose (SG; yeast nitrogen base without amino acids 0.67%, glucose 2% with appropriate supplements: uracil 0.02 mg/mL, amino acids 0.03 mg/mL) or Yeast Peptone Dextrose (YPD; Bacto yeast extract 1%, Bacto peptone 2%, glucose 2%) medium at 35 °C for yeast pathogens (Candida, Cryptococcus) or 30 °C for S. cerevisiae, respectively.

3.2. Chemicals

The chemosensitizing agents (octyl gallate [OG], propyl gallate [PG], 2,3-dihydroxybenzaldehyde [2,3-DHBA], acetylsalicylic acid [AcSA], proguanil) and inhibitors of mitochondrial respiratory chain (MRC) (rotenone, carboxin, thenoyltrifluoroacetone [TTFA], 3-nitropropionic acid [3-NPA], benzhydroxamic acid [BHAM], salicylhydroxamic acid [SHAM], antimycin A [AntA], kresoxim methyl [Kre-Me], pyraclostrobin [PCS], azoxystrobin [AZS], potassium cyanide [KCN], sodium azide [Na-azide], atovaquone [ATQ]) were procured from Sigma Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Each compound was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; absolute DMSO amount: < 1% in media) before incorporation into culture media. In all tests, control plates (i.e., “No treatment”) contained DMSO at levels equivalent to that of cohorts receiving antifungal agents, within the same set of experiments.

3.3. Antifungal Bioassay: Microtiter Plate (Microdilution) Bioassay

Chemosensitizing activity of OG (0.005, 0.01, 0.02, 0.04, 0.08, 0.16, 0.32, 0.64 mM) or 2,3-DHBA (0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, 3.2, 6.4 mM) to PCS (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 µg/mL) was determined by using checkerboard bioassays in microtiter plates (with RPMI 1640 medium; Sigma Co.). To determine changes in MICs of antifungal agents (i.e., PCS and chemosensitizers) in microtiter wells, checkerboard bioassays (0.5 × 105 to 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL) were performed using broth microdilution protocols according to methods outlined by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [32]. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for chemosensitization was defined as the lowest concentration of agent(s) where no fungal growth was visible at 24 and 48 h. All bioassays were performed in triplicate. Statistical analysis was based on [36]. Microtiter plate (microdilution) bioassay was also performed to determine chemosensitizing activity of proguanil (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 μg/mL) to ATQ (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 μg/mL). Minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC), which is the lowest concentration of agents exhibiting ≥ 99.9% fungal death, were determined (after completion of MIC assays) wherein entire volumes of microtiter wells (200 µL) were spread onto individual YPD plates, and cultured for another 48 and 72 h. Compound interactions, Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Indices (FICI) and Fractional Fungicidal Concentration Indices (FFCI) were calculated, as follows: FICI or FFCI = (MIC or MFC of compound A in combination with compound B/MIC or MFC of compound A, alone) + (MIC or MFC of compound B in combination with compound A/MIC or MFC of compound B, alone). Interactions were defined as: “synergistic” (FICI or FFCI ≤ 0.5) or “indifferent” (FICI or FFCI > 0.5–4) [34].

3.4. Antifungal Bioassay: Agar Plate (Yeast Dilution) Bioassay

Petri plate-based yeast dilution bioassays were performed on the wild type and antioxidant mutants (trr1Δ, trr2Δ, tsa1Δ, sod2Δ, yap1Δ) to assess the effects of OG (0.005, 0.01, 0.015, 0.02, 0.025, 0.03, 0.035, 0.04, 0.045, 0.05, 0.1 mM) and 2,3-DHBA (0.005, 0.01, 0.015, 0.02, 0.025, 0.03, 0.035, 0.04, 0.045, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 mM) on the antioxidant system. Similar yeast dilution bioassays were also performed on strains of Cryptococcus or Candida to assess antifungal capacity/effects of OG (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0 mM), 2,3-DHBA (0.0125, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.25, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 mM), PG (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 mM), AcSA (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 mM) or MRC inhibitors (100 μM).

These assays were performed in duplicate on SG agar following previously described protocols [15] as follows: 1 × 106 cells of the wild type or gene deletion mutants of S. cerevisiae, Cryptococcus or Candida, cultured on YPD, were serially diluted 10-fold in SG liquid medium (supplemented with amino acids and uracil, if required) five times, which yields cell dilution cohorts of 106, 105, 104, 103, 100 and 10 cells. Cells from each dilution of respective yeast strains were spotted adjacently on SG agar medium incorporated with antifungal compounds to be tested and incubated at 30 °C or 35 °C for S. cerevisiae or Cryptococcus/Candida, respectively. Results were monitored based on a designated log10 score of the highest dilution where a colony became visible after 3–5 days of incubation, as follows: Score ‘0’—no colonies were visible from any of the dilutions, Score ‘6’—colonies were visible from all dilutions, Score ‘1’—only a colony from the undiluted cells (i.e., 106 cells), ‘2’ only colonies from the undiluted and 105 cells were visible, etc. Therefore, each unit of numerical difference (e.g., 102 vs. 103) was equivalent to a 10-fold difference in the sensitivity of the yeast strain to the treatment.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses, e.g., chemosensitization vs. no chemosensitization, were performed based on [36].

4. Conclusions

In summary, OG- or 2,3-DHBA-based chemosensitization can enhance antifungal activity of PCS in Cryptococcus and Candida. Our results showed that: (1) All Cryptococcus strains (non-fermentors) were sensitive to PCS + OG or 2,3-DHBA; (2) Only selected Candida strains (three C. krusei strains, C. albicans CAN242, C. glabrata CAN252) (fermentors) were sensitive to PCS + OG or 2,3-DHBA; (3) OG was a more potent chemosensitizer than 2,3-DHBA to PCS, where the concentration of OG required to achieve “synergism” was much lower (≥20 times lower) than 2,3-DHBA in either Cryptococcus or Candida strains; (4) “chemosensitization - strain specificity” exists, which reflects differential vulnerability of tested strains to the chemosensitization; (5) OG or 2,3-DHBA disrupt different cellular components in fungi, where Mn-SOD plays a role in fungal tolerance to 2,3-DHBA, while glutathione homeostasis, etc., are responsible for protecting cells from OG-triggered toxicity.

The MRC is recently recognized as a new target for development of clinical antimycotics [24,39]. For example, co-application of AntA (MRC-inhibitory) and BHAM (AOX-inhibitory) significantly increased the activity of triazole drugs, potentiating the antifungal activity of the drugs as fungicidal in R. oryzae (causative agent of mucormycosis) [24]. Also, inhibition of MRC of C. parapsilosis (causing neonatal and device-related infections; See [39] and references therein) enhances susceptibility of this fungal pathogen to caspofungin, a cell wall-targeting drug [39]. Thus, use of a chemosensitizer, as described in this study, would lower the effective dose of an MRC-inhibitory drug, thus lowering potential side effects of these drugs and others that might be co-applied (i.e., azoles, caspofungin, etc.). This lower dosage would render treatment less expensive and safer, thus making their use more acceptable.

In conclusion, OG and/or 2,3-DHBA show potential to serve as antifungal chemosensitizers that in combination with PCS greatly enhance antifungal activity. This capacity was shown to be most effective against Cryptococcus, etiologic agents for the leading cause of death among those suffering from immunocompromised disorders. Chemosensitizers, especially those proven to be safe compounds, such as natural phenolic agents or their structural derivatives, could serve as potential “leads” against yeast pathogens for more effective treatment of mycoses using MRC inhibitory drugs. Determination of precise mechanisms of action of chemosensitization as well as identification of effective MRC-inhibitory drugs which selectively interfere with fungal mitochondrial function, and not human (mammalian), must be ensured through future study.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted under USDA-ARS CRIS Project 5325-42000-037-00D.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Not available.

References

- 1.Sobel J.D., Wiesenfeld H.C., Martens M., Danna P., Hooton T.M., Rompalo A., Sperling M., Livengood C., 3rd, Von Thron J., et al. Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:876–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfaller M.A., Diekema D.J., Sheehan D.J. Interpretive breakpoints for fluconazole and Candida revisited: a blueprint for the future of antifungal susceptibility testing. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006;19:435–447. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.435-447.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens D.A., Espiritu M., Parmar R. Paradoxical effect of caspofungin: reduced activity against Candida albicans at high drug concentrations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3407–3411. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3407-3411.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shingu-Vazquez M., Traven A. Mitochondria and fungal pathogenesis: drug tolerance, virulence, and potential for antifungal therapy. Eukaryot. Cell. 2011;10:1376–1383. doi: 10.1128/EC.05184-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MedlinePlus. Atovaquone. [(accessed on 17 June 2013)]. Available online: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a693003.html.

- 6.Srivastava I.K., Rottenberg H., Vaidya A.B. Atovaquone, a broad spectrum antiparasitic drug, Collapses mitochondrial membrane potential in a malarial parasite. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:3961–3966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.3961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longo V.D., Gralla E.B., Valentine J.S. Superoxide dismutase activity is essential for stationary phase survival in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mitochondrial production of toxic oxygen species in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:12275–12280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant C.M. Role of the glutathione/glutaredoxin and thioredoxin systems in yeast growth and response to stress conditions. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;39:533–541. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J.H., Chan K.L., Mahoney N., Campbell B.C. Antifungal activity of redox-active benzaldehydes that target cellular antioxidation. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2011;10:23. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillen F., Evans C.S. Anisaldehyde and veratraldehyde acting as redox cycling agents for H2O2 production by Pleurotus eryngii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994;60:2811–2817. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.2811-2817.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacob C. A scent of therapy: Pharmacological implications of natural products containing redox-active sulfur atoms. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006;23:851–863. doi: 10.1039/b609523m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa-de-Oliveira S., Sampaio-Marques B., Barbosa M., Ricardo E., Pina-Vaz C., Ludovico P., Rodrigues A.G. An alternative respiratory pathway on Candida krusei: implications on susceptibility profile and oxidative stress. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012;12:423–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2012.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue K., Tsurumi T., Ishii H., Park P., Ikeda K. Cytological evaluation of the effect of azoxystrobin and alternative oxidase inhibitors in Botrytis cinerea. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012;326:83–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujita K., Kubo I. Antifungal activity of octyl gallate. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002;79:193–201. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J.H., Mahoney N., Chan K.L., Molyneux R.J., May G.S., Campbell B.C. Chemosensitization of fungal pathogens to antimicrobial agents using benzo analogs. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008;281:64–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sebolai O.M., Pohl C.H., Botes P.J., van Wyk P.W., Mzizi R., Swart C.W., Kock J.L. Distribution of 3-hydroxy oxylipins and acetylsalicylic acid sensitivity in Cryptococcus species. Can. J. Microbiol. 2008;54:111–118. doi: 10.1139/W07-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruy F., Vercesi A.E., Kowaltowski A.J. Inhibition of specific electron transport pathways leads to oxidative stress and decreased Candida albicans proliferation. J. Bioenerg. Biomembrane. 2006;38:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s10863-006-9012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McIntosh L. Molecular biology of the alternative oxidase. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:781–786. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.3.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal A.K., Tripathi S.K., Xu T., Jacob M.R., Li X.C., Clark A.M. Exploring the molecular basis of antifungal synergies using genome-wide approaches. Front. Microbiol. 2012;3:115. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell B.C., Chan K.L., Kim J.H. Chemosensitization as a means to augment commercial antifungal agents. Front. Microbiol. 2012;3:79. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavigne J.P., Brunel J.M., Chevalier J., Pages J.M. Squalamine, an original chemosensitizer to combat antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010;65:799–801. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niimi K., Harding D.R., Parshot R., King A., Lun D.J., Decottignies A., Niimi M., Lin S., Cannon R.D., Goffeau A., et al. Chemosensitization of fluconazole resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and pathogenic fungi by a d-octapeptide derivative. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1256–1271. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1256-1271.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batova M., Klobucnikova V., Oblasova Z., Gregan J., Zahradnik P., Hapala I., Subik J., Schuller C. Chemogenomic and transcriptome analysis identifies mode of action of the chemosensitizing agent CTBT (7-chlorotetrazolo[5,1-c]benzo[1,2,4]triazine) BMC Genomics. 2010;11:153. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirazi F., Kontoyiannis D.P. Mitochondrial respiratory pathways inhibition in Rhizopus oryzae potentiates activity of posaconazole and itraconazole via apoptosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. C. neoformans Cryptococcus. [(accessed on 17 June 2013)]. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/cryptococcosis-neoformans/

- 26.Kim J.H., Campbell B.C., Mahoney N., Chan K.L., Molyneux R.J., May G.S. Enhancement of fludioxonil fungicidal activity by disrupting cellular glutathione homeostasis with 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007;270:284–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martins V.d.P., Dinamarco T.M., Curti C., Uyemura S.A. Classical and alternative components of the mitochondrial respiratory chain in pathogenic fungi as potential therapeutic targets. J. Bioenerg. Biomembrane. 2011;43:81–88. doi: 10.1007/s10863-011-9331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robles-Martinez L., Guerra-Sanchez M.G., Flores-Herrera O., Hernandez-Lauzardo A.N., Velazquez-Del Valle M.G., Pardo J.P. The mitochondrial respiratory chain of Rhizopus stolonifer (Ehrenb.:Fr.) Vuill. Arch. Microbiol. 2013;195:51–61. doi: 10.1007/s00203-012-0845-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sierra-Campos E., Valdez-Solana M.A., Matuz-Mares D., Velazquez I., Pardo J.P. Induction of morphological changes in Ustilago maydis cells by octyl gallate. Microbiology. 2009;155:604–611. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.020800-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saccharomyces Genome Database. [(accessed on 17 June 2013)]. Available online: http://www.yeastgenome.org.

- 31.Srivastava I.K., Vaidya A.B. A mechanism for the synergistic antimalarial action of atovaquone and proguanil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1334–1339. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arendrup M.C., Cuenca-Estrella M., Lass-Florl C., Hope W. EUCAST technical note on the EUCAST definitive document EDef 7.2: method for the determination of broth dilution minimum inhibitory concentrations of antifungal agents for yeasts EDef 7.2 (EUCAST-AFST) Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18:E246–E247. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hill P., Kessl J., Fisher N., Meshnick S., Trumpower B.L., Meunier B. Recapitulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae of cytochrome b mutations conferring resistance to atovaquone in Pneumocystis jiroveci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2725–2731. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2725-2731.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Odds F.C. Synergy, Antagonism, And what the chequerboard puts between them. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003;52:1. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meletiadis J., Antachopoulos C., Stergiopoulou T., Pournaras S., Roilides E., Walsh T.J. Differential fungicidal activities of amphotericin B and voriconazole against Aspergillus species determined by microbroth methodology. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3329–3337. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00345-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirkman T.W. Statistics to use. [(accessed on 17 June 2013)]. Available online: http://www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats/

- 37.Fernandes L., Rodrigues-Pousada C., Struhl K. Yap, a novel family of eight bZIP proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae with distinct biological functions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:6982–6993. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.6982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee J., Godon C., Lagniel G., Spector D., Garin J., Labarre J., Toledano M.B. Yap1 and Skn7 control two specialized oxidative stress response regulons in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:16040–16046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chamilos G., Lewis R.E., Kontoyiannis D.P. Inhibition of Candida parapsilosis mitochondrial respiratory pathways enhances susceptibility to caspofungin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50:744–747. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.2.744-747.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]