Abstract

Objective

Due to the defects in skin barrier function and immune response, burn patients who survive the acute phase of a burn injury are at a high risk of nosocomial infection (NI). The aim of this study is to evaluate the impacts of NI on length of stay (LOS) and hospital mortality in burn patients using a multistate model.

Design and setting

A retrospective observational study was conducted in burn unit and intensive care unit in the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, China.

Participants

Data were obtained from 1143 records of patients admitted with burn between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2016.

Methods

Risk factors for NIs were determined by binary logistic regression. The extended Cox model with time-varying covariates was used to determine the impact of NIs on hospital mortality, and cumulative incidence functions were calculated. Multiple linear regression analysis was applied to detect the variables associated with LOS. Using a multistate model, the extra LOS due to NI were determined.

Results

15.8% of total burn patients suffered from NIs and incidence density of NIs was 9.6 per 1000 patient-days. NIs significantly increased the rate of death (HR 4.266, 95% CI 2.218 to 8.208, p=0.000). The cumulative probability of death for patients with NI was greater that for those without NI. The extra LOS due to NIs was 17.68 days (95% CI 11.31 to 24.05).

Conclusions

Using appropriate statistical methods, the present study further illustrated that NIs were associated with the increased cumulative incidence of burn death and increased LOS in burn patients.

Keywords: burn, nosocomial infection, length of stay, mortality, multi-state model

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Using multistate and competing risks analysis, the present study assessed the impact of nosocomial infections (NIs) on hospital mortality and length of stay (LOS) in burn patients.

Some potential factors, such as nursing protocols and the history of immunosuppression drugs, that may be associated with NI, LOS and mortality were not recorded.

This study was performed in a single centre and the results need to be further confirmed by multiple centre trials.

Introduction

Burn injury, as a common cause of morbidity and mortality, has been recognised as a global public health problem. According to the data from WHO, burns account for an estimated 300 000 deaths each year.1 Previous evidence illustrated that burn shock and inhalation injury were the major cause of early death among patients with burn injury.2 3 Due to the advance in fluid resuscitation, surgical approach, organ function protection, antibiotic innovation and other adjunct strategies, the early mortality of burn patients decreased dramatically over the last 30 years.4 5 On the other hand, because of the defects in skin barrier function and immune response, burn patients who survive the acute phase of a burn injury are at a high risk of acquiring nosocomial infection (NI).6

It has been reported that about 30%–80% of burn patients suffered from NIs.7–9 Nevertheless, the exact impact of NIs on the length of stay (LOS) and mortality of burn patients remains elusive. Williams et al 10 investigated the predominant causes of death in burned paediatric patients. They found that infection is the leading cause of death after burn injury. A recent study reported an incidence density of 14.7 infections/1000 patient-days in burn patients.11 Nevertheless, the study illustrated that NIs were not a risk factor for mortality, using logistic regression, after adjusting for confound variables.11 It should be noted that NI is a time-varying factor, and it can develop at any time after admission. Matched cohort study is the most commonly used method for estimating LOS associated with NIs. However, different matching factors were used in different studies, and it may be difficult to identify appropriate matching factors for NIs.12 More importantly, the time-dependent characteristics of NIs imply that infection can impact on LOS only after the infection has started.12 13 So, appropriate statistical methods for estimating the risk of death and LOS due to NI among burn patients would be helpful in making medical decisions and developing policy. Multistate modelling is a method to avoid time-dependent bias, and it is a useful way of describing a process in which a patient moves through a series of states in continuous time.12 13 The aim of this study was to determine the impacts of NI on LOS and hospital mortality in burn patients using a multistate model.

Materials and methods

Patients

A retrospective study was conducted in burn unit and intensive care unit (ICU) in the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, China. The burn unit has 72 beds and there are 50 beds in the ICU. After approval by the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, data of total 1143 patients admitted with burn were collected during January 2013 to December 2016. Inclusion criteria: (1) age of 0–99 years; (2) admission to hospital no later than 3 days postburn; (3) LOS >48 hours. As the present study was an observational and retrospective study, informed consent was waived by the Medical Ethics Committee.

Data collection

NI in burn patients was defined as infection occurring 48 hours after hospital admission. There were four main types of NIs (burn wound infection (BWI), bloodstream infection (BSI), pneumonia, urinary tract infection, UTI) according to the criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).14 Briefly, BWI was defined as patient has a change in burn wound appearance, such as rapid eschar separation, dark brown, black or violaceous discolouration of eschar and at least one of the following: histological examination of burn biopsy shows invasion of organisms into adjacent viable tissue or positive blood culture without other identifiable infection. BSI includes laboratory-confirmed BSI and clinical sepsis. Patient with laboratory-confirmed BSI must have a recognised pathogen cultured from one or more blood cultures and organism cultured from blood is not related to an infection at another site. Clinical sepsis must meet the following clinical signs or symptoms with no other recognised cause: fever (T>38°C), hypotension (systolic pressure ≤90 mm Hg) or oliguria (<20 cm3/hour); blood culture not done or no organisms or antigen detected in blood; and no apparent infection at another site and physician instituted treatment for sepsis. Patients had rales or dullness to percussion on physical examination of the chest or a chest radiographic examination that showed new or progressive infiltrate or consolidation, cavitation, or pleural effusion and new onset of purulent sputum or change in character of sputum were diagnosed with pneumonia. Finally, UTI patient with the following signs or symptoms with no other recognisable cause: fever (T>38°C), urgency, frequency, dysuria or suprapubic tenderness and at least one of the following: (1) positive dipstick for leucocyte esterase and/or nitrate; (2) positive urine microscopy or urine culture.

Patients with a history of smoke or fire exposure in a closed space or maxillofacial burn were suspected to have inhalation injury. The diagnosis of inhalation injury was made if the suspected patients had physical findings including changes in voice and carbonaceous sputum production or had bronchoscopic evidence.15

The characteristics of NI including time, site and pathogen were recorded. For patients with NI at the same site, only the first episode of it was analysed. The potential factors which are associated with NIs, LOS and mortality were collected, including gender, age, history of diabetes, date of admission, burn types (flame, scalding, electric and others), burn size and depth and inhalation injury.7–9 Additionally, the dates of discharge and death were also recorded.

Management

Resuscitation was performed according to the modified Evans (Ruijin) formula as described by the previous paper.16 17 Dressings were changed every 1–3 days by doctors. Silver sulfadiazine was applied on deep partial-thickness and full-thickness burns. For full-thickness burns, early surgical excision of burn eschar and biological closure were performed when the patients’ condition permits. Prophylactic antibiotic therapy was performed in patients who needing surgical intervention (perioperative period of debridement or auto skin grafting) or requiring mechanical ventilation. The strategy of prophylactic antibiotic therapy was mainly based on the advice of doctors from the department of microbiology and infectious diseases and the previous antibiotic susceptibility pattern of the centre. Additionally, patients met CDC criteria were treated with antibiotics. When a pathogen was identified, antibiotics were adjusted according to the results of isolate’s susceptibility. The duration of antibiotics therapy is decided by the treating physician based on clinical symptoms, blood culture results as well as other infection markers.

Statistical analysis

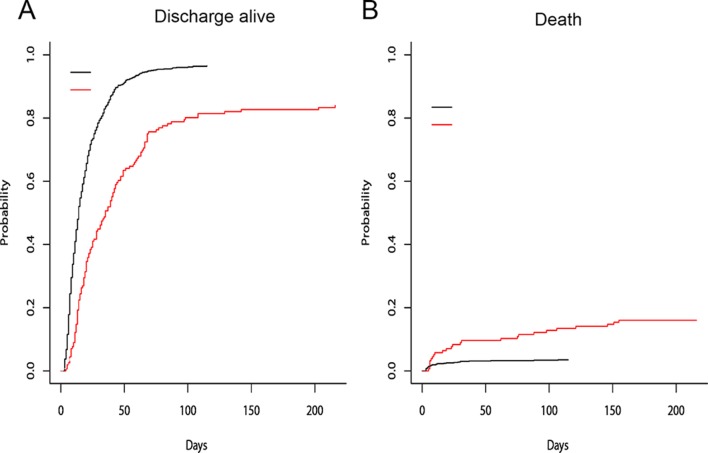

Data are presented as a percentage of a percentage of total or IQRs (25th and 75th percentiles), as appropriate. Mann-Whitney U test is used to analysis continuous variables while categorical variables were analysed by the χ2 test. Univariate analysis was performed to assess the potential variables associated with NI and hospital mortality. Variables included in the univariate analysis were age, sex, diabetes, burn types (flame, scalding, electric and others), total body surface area (TBSA) (<10%, 10%–29%, ≥30%), full thickness of burn and inhalation injury. The variables with p<0.05 were used for further analysis. A Cox model was used to determine the risk factors for NI and death. In the Cox model, NI was modelled as a time-varying covariate by the ‘survival’ package in R. Cumulative incidence functions were calculated by the ‘cmprsk’ package. Additionally, linear regression analysis was applied to detect the variables associated with hospital LOS. The ‘etm’ package in R was performed to calculate the difference in LOS between patients with and without NI. The code used in the present study was available at https://CRAN.R-project.org/. There are four states in our multistate model: admission (state 0), NI (state 1), discharge alive (state 2) and death (state 3). After admission, patients with NIs move from state 0 to state 1, then state 2 or state 3, while non-infected patients directly move from state 0 to state 2 or state 3. The detail information about this multistate model is shown in figure 1. R V.3.4.1 software and SPSS V.18.0 were used to prepare and analysis the data. Statistical significance was expressed as both p values and 95% CIs. A two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Multistate model. Our model including four states: admission, nosocomial infection, discharge alive and death. After admission, patients may be infected or not, then they may be discharge alive or die.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in developing the hypothesis or research questions. No patients were involved in the development of the outcome measures. No patients were involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants.

Results

Patient characteristics

During the study period, a total of 1143 burn patients were admitted to the hospital. One hundred and fifty-seven burn patients were ineligible by exclusion criteria and 986 patients were included in the final analysis. Demographic and burn-related characteristics are shown in table 1. 65.1% of the patients were men and 34.9% were women. The median age was 37 (IQR, 18–49) years and 7.1% were elderly patients (65 years and older). 47.6% of the patients had <10% TBSA burn, 30.8% had 10%–29% TBSA burn and 21.6% of burn patients with TBSA more than 30%. The main burn type is flame (78.2%), followed by scalding (9.7%), electric (7.4%) and other types (4.7%). There were 46 (4.7%) patients had inhalation injury. The hospital morality was 5.5% (54/986) and the median length of hospital stay was 14 (IQR 8–28).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristic of burn patients with and without NI

| Variables | Total n=986 | NI n=156 | No-NI n=830 | P values |

| Male, n (%) | 642 (65.1) | 105 (64.7) | 537 (67.3) | 0.530 |

| Age (years), median (25th, 75th) | 37 (18, 49) | 37 (17, 49) | 37 (24, 37) | 0.470 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 38 (3.9) | 11 (7.1) | 27 (3.3) | 0.024 |

| TBSA, n (%) | ||||

| <10% | 469 (47.6) | 55 (35.3) | 414 (49.9) | 0.031 |

| 10%–29% | 304 (30.8) | 38 (24.4) | 266 (32.0) | 0.056 |

| ≥30% | 213 (21.6) | 63 (40.3) | 150 (18.1) | 0.000 |

| Full thickness burn, n (%) | 221 (22.4) | 60 (38.5) | 161 (19.4) | 0.000 |

| Inhalation injury, n (%) | 46 (4.7) | 38 (24.3) | 8 (1.0) | 0.000 |

| Burn type, n (%) | ||||

| Flame | 771 (78.2) | 118 (75.6) | 653 (84.7) | 0.400 |

| Scalding | 96 (9.7) | 11 (7.1) | 85 (10.2) | 0.218 |

| Electric | 73 (7.4) | 15 (9.6) | 58 (7.0) | 0.250 |

| Others | 46 (4.7) | 12 (7.7) | 34 (4.1) | 0.051 |

| Length of hospital stay median (25th, 75th) | 14 (8, 28) | 27 (13.25, 57.75) | 13 (7, 24) | 0.000 |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 54 (5.5) | 25 (16.0) | 29 (3.5) | 0.000 |

Values of P<0.05 are given in bold.

NI, nosocomial infection; TBSA, total body surface area.

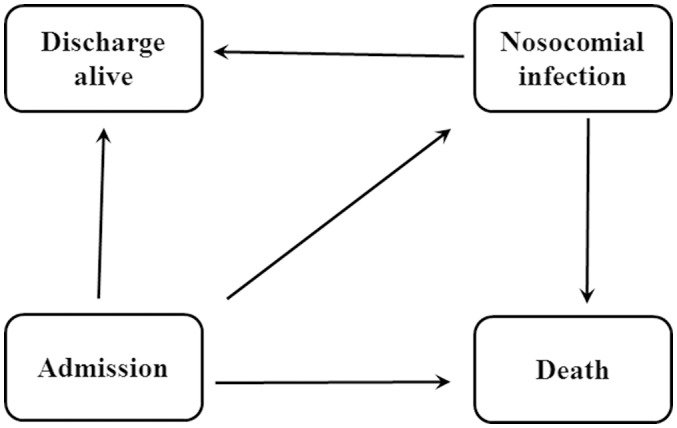

Characteristics of NIs

One hundred and fifty-six burn patients had 209 NIs, and the median time from admission to the NI was 7 days (IQR 5–10). Over all NI rate was 9.6 per 1000 patient-days. Among all NIs, BWI was the most frequent infection (45.9%), followed by BSI (24.8%), pneumonia (23.4%) and UTI (5.7%) (figure 2A). As shown in figure 2B a total of 237 micro-organisms were isolated. The most common pathogens was Acinetobacter baumannii (30.8%), followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (21.5%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (16.9%) and Staphylococcus spp (11%) (figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Characteristics of nosocomial infections. BWI, burn wound infection; BSI, bloodstream infection; PI, pulmonary infection; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Univariate analysis indicated that there were significant differences in diabetes, TBSA <10%, TBSA ≥30%, full thickness burn, inhalation injury and LOS between burn patients with and without NIs (table 1). Using a Cox regression model, there was a statistically significant increased OR for NI in patients with full thickness burn (HR 1.799; 95% CI 1.288 to 2.511, p=0.000) and inhalation injury (OR 3.326; 95% CI 2.169 to 5.102, p=0.000), TBSA (HR1.189; 95% CI 1.005 to 1.407, p=0.043) (table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the Cox proportional hazard analysis of nosocomial infection

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P values |

| LOS | 1.002 | 0.996 to 1.007 | 0.547 |

| TBSA | 1.189 | 1.005 to 1.407 | 0.043 |

| Full thickness burn | 1.799 | 1.289 to 2.511 | 0.000 |

| Inhalation injury | 3.326 | 2.169 to 5.102 | 0.000 |

| Diabetes | 1.586 | 0.856 to 2.939 | 0.143 |

Values of P<0.05 are given in bold.

LOS, length of stay; TBSA, total body surface area.

Impact of NIs on hospital death of burn patients

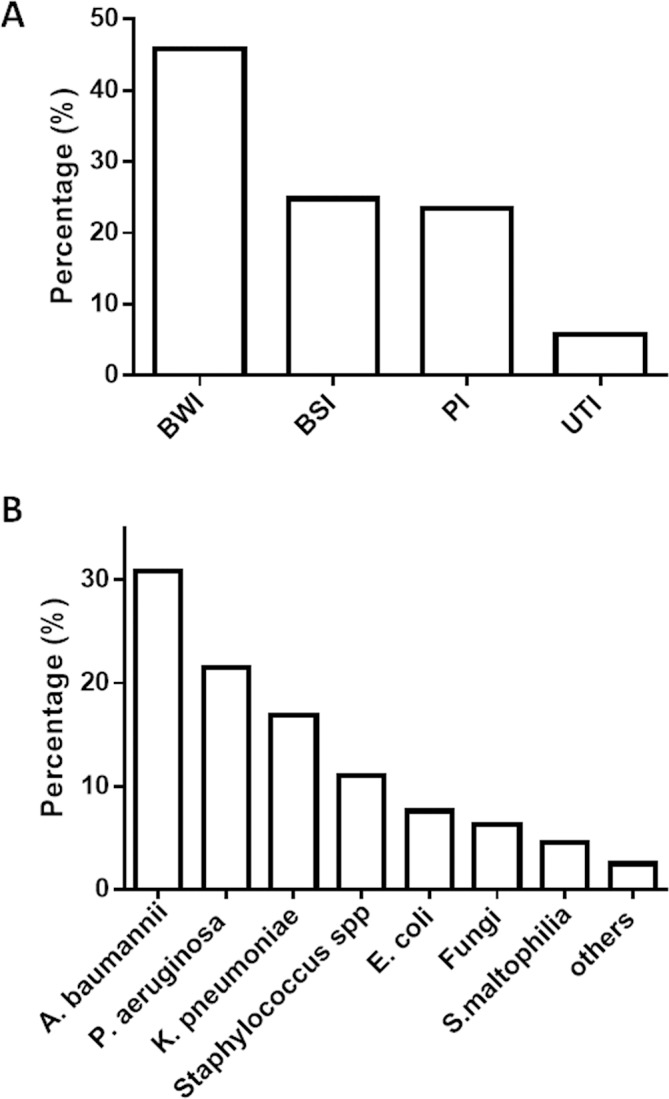

As shown in table 1, the hospital mortality of patients with and without NI was 16.0% and 3.5%, respectively. Univariate analysis indicated that the hospital mortality of patients with NIs was higher than those without NIs (online supplementary table S1). Using a Cox regression model with NI modelled as a time-varying covariate, we found the risk of hospital death for patients with NI was 5.92 times higher than that for patients without it (95% CI 3.098 to 11.310, p<0.001). After adjusting for age, gender, TBSA and inhalation injury, the risk of hospital death for patients with NI was 4.266 times higher than for patients without NI (95% CI 2.218 to 8.208, p=0.000) (table 3, online supplementary table S1). Cumulative incidence functions for death were shown in figure 3A. The cumulative probability of discharge was consistently lesser for an infected patient (figure 3A). As shown in figure 3B, the cumulative probability of death for a patient with NI was greater that for a patient without NI.

Table 3.

Results of the Cox proportional hazard analysis of hospital death

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P values |

| Nosocomial infection | 4.266 | 2.218 to 8.208 | 0.000 |

| TBSA | 1.374 | 1.034 to 1.825 | 0.028 |

| Inhalation injury | 2.824 | 1.448 to 5.508 | 0.002 |

| Age | 1.003 | 0.991 to 1.016 | 0.608 |

| Gender | 1.212 | 0.667 to 2.201 | 0.528 |

Values of P< 0.05 are given in bold.

TBSA, total body surface area.

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence functions for discharge (A) and death (B) in burn patients. Read lines: nosocomial infection; black lines: no nosocomial infection.

bmjopen-2017-020527supp001.pdf (452.6KB, pdf)

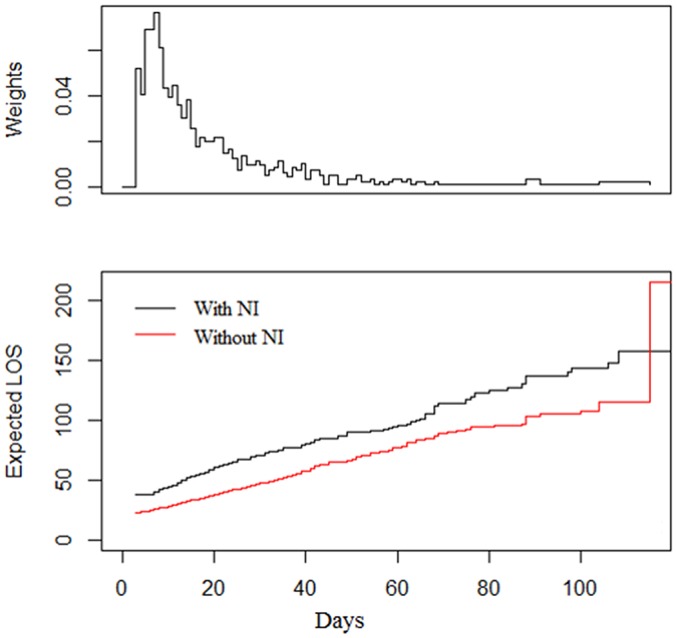

Extra LOS

As shown in figure 1, the median LOS for patients without NI was 13 days (IQR 7–24). For patients with NI, the median LOS was 27 days (IQR 13.25–57.75). Because the LOS distribution is positively skewed, the logarithm (base 10) of LOS was used as the response variable in multiple linear regressions. Based on the results of multiple linear regressions, NI was associated with increased LOS in burn patients. Other variables associated with LOS were TBSA, electric burn, flame burn, full thickness (table 4). Using a multistate model, the extra LOS due to NI was 17.68 days (95% CI 11.31 to 24.05, SE 3.25, p<0.001) (figure 4).

Table 4.

Results of multiple linear regressions analysis of length of stay (days)

| Variables | Β | 95% CI | P values |

| TBSA | 0.085 | 0.056 to 0.113 | 0.000 |

| Full thickness burn | 0.105 | 0.052 to 0.157 | 0.000 |

| Electric burn | 0.228 | 0.129 to 0.328 | 0.000 |

| Flame burn | 0.093 | 0.031 to 0.155 | 0.003 |

| Nosocomial infection | 0.244 | 0.184 to 0.305 | 0.000 |

TBSA, total body surface area.

Figure 4.

Extra LOS in patients without (red line) and with (black line) infection. LOS, length of stay; NI, nosocomial infection.

Discussion

Burn patients are at high risk for local and systemic infections. Although infection control programme has been performed in most burn centres and hospitals, the incidence of NI remains high. Alp et al reported that 11% of burn patients were suffered from NI and incidence density was 14.7 per 1000 patient-days.11 Recently, a prospective cohort study was conducted in six major US burn centres to determine the association between burn size and the morbidity and mortality of burns. It found that in patients who have >20% TBSA burn and need for surgical intervention, the incidence of NI was 70%.18 In the present study, incidence density of NI was 9.6 per 1000 patient-days which was less than that reported by Alp et al and Jeschke et al. BWI was the most common infections in our burn centre. A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa accounted for about 50% of total isolates, and A. baumannii was the predominant pathogen. Previously study illustrated that A. baumannii was the most common Gram-negative pathogen in burn patients.9 According to the data published by Alp et al,11 57% of isolates from burns was A. baumannii in 2009. Nowadays, A. baumannii has emerged as an important pathogen causing NIs in China. Rigorous antibiotic stewardship and infection control measures were applied to prevent the spread of A. baumannii infections.19

Many factors contribute to NIs in burns, including burn injury-induced immunosuppression.6–9 Clinical and experimental evidence illustrated that severe systemic inflammation after burn injuries can lead to a compensatory anti-inflammatory response, which is characterised by decreased number of T helper lymphocytes, increased suppressive activity of regulatory T cells (Tregs) which specialised for immune suppression, as well as elevated levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines.20–22 Inhibition of Tregs attenuates postburn sepsis has been confirmed by an experimental study.23 In addition, we also observed that full thickness burn, TBSA and inhalation injury are the risk factors for NIs in burn patients. The most notable finding in this study was the association between NIs and hospital mortality in burn patients. It has been reported that, in patients with more than 40% TBSA, over 70% of deaths were related to sepsis resulting from BWIs and other infection complications.6 8 9 11 24 Nevertheless, a study illustrated that NI was a risk factor for mortality in univariate analysis, but it was not found as a risk factor for mortality in the stepwise forward logistic regression undertaken to control effect of confound variables.11 The different statistical method may contribute to the different results. In the present study, NI was modelled as a time-varying factor in a competing risk model. The results illustrated that the risk of hospital death for burns with NI was 4.266 times higher than that for non-infected patients, and the cumulative probability of discharge was consistently lesser for an infected patient. Burn size was the strongest predictor of mortality in burns, as illustrated by previous studies.18 25 26 In the present study, we found that TBSA is a risk factor for hospital death in burn patients. Additionally, inhalation injury usually causes pulmonary and systemic complications which greatly increases the risk of death after burn and the results of our study confirmed this.25 26

The association between NI and LOS has been illustrated by many studies. The median LOS was about twofold higher in patients with trauma with NI compared with patients without infection.27 Among patients with critical illness, NI increased the LOS by approximately 18 days per patients.28 NI after burn has been considered as a risk factor for prolonged LOS. Shupp et al reported that BSI was associated with longer hospital LOS in burn patients.29 Nevertheless, there were no studies to assess the exact impact of NIs on LOS in burns. Additionally, the time-dependent nature of NIs implies that infection can impact on LOS only after the infection has started. While analysing the impact of NIs on LOS, the duration of hospitalisation prior to the NIs should be considered. So, a multistate model was used in the present study to estimation of extra LOS caused by NI. We found that the extra LOS due to NI in burn patients was 17.68 days.

There are some limitations in the present study. Initially, efforts used to prevent NI, such as antibiotic treatment and surgery, may have been started before the diagnosis was made. So, our assessment of the impact of NI on LOS and hospital mortality should be regarded as a lower estimate. Second, as an observational and retrospective study, some potential factors, such as nursing protocols and the use of antipeptic ulcer or immunosuppression drugs, that may be associated with NIs, LOS and death were not available. Furthermore, factors, including mechanical ventilation and application of antibiotics, may also influence the incidence of NIs. These factors need to be taken into consideration in the prospective studies. Additionally, the present study was performed in a single centre and the results need to be further confirmed by multiple centre trials. Finally, there were no patients and public involved in this retrospective observational study. As patient and public involvement is important for a clinical research,30 it needs to be done in the future studies.

Conclusion

The present study provided additional information about the impact of NI on LOS and hospital mortality in burn patients. Using competing risk and multistate model, we found that NI was associated with the increased cumulative incidence of burn death. The expected extra LOS due to NIs among burn patients was 17.68 days. The model used in the present study may help to improve the accuracy of estimates of LOS and incidence of death due to NIs in burns.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: H-LG and Z-JL wrote the protocol, participated in the data analysis and contributed to writing this manuscript. G-JZ, X-WL, J-JX and C-JL collected the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (grant number 81871583) and Wenzhou Municipal Science and Technology Project (grant numbers Y2013010, 2015KYB239).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Mock C, Peck M, Peden M, Krug E, et al. A WHO plan for burn prevention and care. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bloemsma GC, Dokter J, Boxma H, et al. . Mortality and causes of death in a burn centre. Burns 2008;34:1103–7. 10.1016/j.burns.2008.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ryan CM, Schoenfeld DA, Thorpe WP, et al. . Objective estimates of the probability of death from burn injuries. N Engl J Med 1998;338:362–6. 10.1056/NEJM199802053380604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tompkins RG. Survival from burns in the new millennium: 70 years’ experience from a single institution. Ann Surg 2015;261:263–8. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tompkins RG, Liang MH, Lee AF, et al. . The American Burn Association/Shriners Hospitals for Children Burn Outcomes Program: a progress report at 15 years. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73:S173–8. 10.1097/TA.0b013e318265c53e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Church D, Elsayed S, Reid O, et al. . Burn wound infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006;19:403–34. 10.1128/CMR.19.2.403-434.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keen EF, Robinson BJ, Hospenthal DR, et al. . Incidence and bacteriology of burn infections at a military burn center. Burns 2010;36:461–8. 10.1016/j.burns.2009.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Öncül O, Öksüz S, Acar A, et al. . Nosocomial infection characteristics in a burn intensive care unit: analysis of an eleven-year active surveillance. Burns 2014;40:835–41. 10.1016/j.burns.2013.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leseva M, Arguirova M, Nashev D, et al. . Nosocomial infections in burn patients: etiology, antimicrobial resistance, means to control. Ann Burns Fire Disasters 2013;26:5–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Williams FN, Herndon DN, Hawkins HK, et al. . The leading causes of death after burn injury in a single pediatric burn center. Crit Care 2009;13:R183 10.1186/cc8170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alp E, Coruh A, Gunay GK, et al. . Risk factors for nosocomial infection and mortality in burn patients: 10 years of experience at a university hospital. J Burn Care Res 2012;33:379–85. 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318234966c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Angelis G, Murthy A, Beyersmann J, et al. . Estimating the impact of healthcare-associated infections on length of stay and costs. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010;16:1729–35. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao GJ, Li D, Zhao Q, et al. . Incidence, risk factors and impact on outcomes of secondary infection in patients with septic shock: an 8-year retrospective study. Sci Rep 2016;6:38361 10.1038/srep38361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control 2008;36:309–32. 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walker PF, Buehner MF, Wood LA, et al. . Diagnosis and management of inhalation injury: an updated review. Crit Care 2015;19:351 10.1186/s13054-015-1077-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shi Y, Zhang X, Huang BG, et al. . Severe burn injury in late pregnancy: a case report and literature review. Burns Trauma 2015;3:2 10.1186/s41038-015-0002-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen Z, Yuan K. Another important factor affecting fluid requirement after severe burn: a retrospective study of 166 burn patients in Shanghai. Burns 2011;37:1145–9. 10.1016/j.burns.2011.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jeschke MG, Pinto R, Kraft R, et al. . Morbidity and survival probability in burn patients in modern burn care. Crit Care Med 2015;43:808–15. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen B, Lx H, Hu B, et al. . Expert consensus document on acinetobacter baumannii infection diagnosis, treatment and prevention in China. Zhong Hua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2012;92:76–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH. The cellular basis of post-burn immunosuppression: macrophages and mediators. Int J Mol Med 2002;10:239–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parment K, Zetterberg A, Ernerudh J, et al. . Long-term immunosuppression in burned patients assessed by in vitro neutrophil oxidative burst (Phagoburst). Burns 2007;33:865–71. 10.1016/j.burns.2006.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang LF, Yao YM, Dong N, et al. . Association between regulatory T cell activity and sepsis and outcome of severely burned patients: a prospective, observational study. Crit Care 2010;14:R3 10.1186/cc8232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu QY, Yao YM, Yu Y, et al. . Astragalus polysaccharides attenuate postburn sepsis via inhibiting negative immunoregulation of CD4+ CD25(high) T cells. PLoS One 2011;6:e19811 10.1371/journal.pone.0019811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fitzwater J, Purdue GF, Hunt JL, et al. . The risk factors and time course of sepsis and organ dysfunction after burn trauma. J Trauma 2003;54:959–66. 10.1097/01.TA.0000029382.26295.AB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith DL, Cairns BA, Ramadan F, et al. . Effect of inhalation injury, burn size, and age on mortality: a study of 1447 consecutive burn patients. J Trauma 1994;37:655–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li H, Yao Z, Tan J, et al. . Epidemiology and outcome analysis of 6325 burn patients: a five-year retrospective study in a major burn center in Southwest China. Sci Rep 2017;7:46066 10.1038/srep46066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glance LG, Stone PW, Mukamel DB, et al. . Increases in mortality, length of stay, and cost associated with hospital-acquired infections in trauma patients. Arch Surg 2011;146:794–801. 10.1001/archsurg.2011.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen YY, Chou YC, Chou P. Impact of nosocomial infection on cost of illness and length of stay in intensive care units. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2005;26:281–7. 10.1086/502540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shupp JW, Pavlovich AR, Jeng JC, et al. . Epidemiology of bloodstream infections in burn-injured patients: a review of the national burn repository. J Burn Care Res 2010;31:521–8. 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181e4d5e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Price A, Schroter S, Snow R, et al. . Frequency of reporting on patient and public involvement (PPI) in research studies published in a general medical journal: a descriptive study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020452 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020527supp001.pdf (452.6KB, pdf)