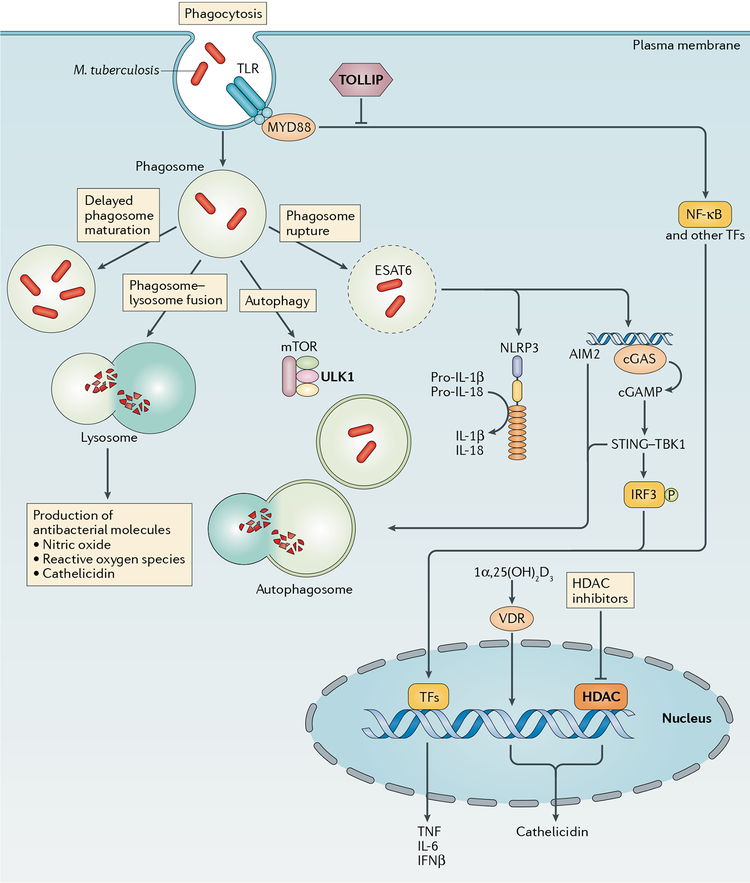

Fig. 2 |. Macrophage-mediated resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Macrophages can provide resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection at multiple points in the infection process, including the initial uptake of bacilli into phagosomes and through any of the possible fates of these phagosomes. These fates include effective (versus delayed) phagosome maturation (resulting in the generation of microbicidal products, such as nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species and cathelicidin), fusion with the lysosome (resulting in degradation of the phagosomal contents), recruitment of autophagy factors (resulting ultimately in autophagosome-lysosome fusion) or phagosomal escape of bacteria into the cytosol. Pro-inflammatory cytokine production may result from Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligation or the recognition of signals following phagosomal rupture, including inflammasome-triggered maturation of pro-IL-1β or pro-IL-18 and recognition of cytosolic M. tuberculosis DNA by cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) and the resultant stimulator of interferon genes (STING)-dependent interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3)-driven transcriptional response. Vitamin D3 receptor (VDR)-dependent transcription, which requires prior activation of vitamin D to 1α,25(OH)2D3 through TLR or IFNγ signalling events, results in cathelicidin expression. Genetic and cellular evidence exists for a role for the negative TLR regulator Toll-interacting protein (TOLLIP), the autophagy factor Unc51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) and histone deacetylases (HDACs; which are master transcriptional regulators) in resistance. AIM2, absent in melanoma 2; cGAMP, cyclic GMP-AMP; ESAT6, 6 kDa early secretory antigenic target; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; MYD88, myeloid differentiation primary response protein MYD88; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NLRP3, NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing 3; TBK1, TANK-binding kinase 1; TFs, transcription factors; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.