Abstract

Introduction

Community-based clergy are highly engaged in helping seriously ill patients address spiritual concerns at the end of life (EOL). While they desire EOL training, no data exists in guiding how to conceptualize a clergy-training program.

Objective

To identify best practices in an EOL training program for community clergy.

Design

As part of the National Clergy Project on End-of-Life Care the project conducted key informant interviews and focus groups with active clergy.

Setting

Five U.S. states (California, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, and Texas)

Participants

A diverse purposive sample of 35 active clergy representing pre-identified racial, educational, theological, and denominational categories hypothesized to be associated with more intensive utilization of medical care at the EOL.

Main Outcome(s) and Measure(s)

We assessed suggested curriculum structure and content for clergy EOL training through interviews and focus groups for the purpose of qualitative analysis.

Results

Thematic analysis identified key themes around curriculum structure, curriculum content, and issues of tension. Curriculum structure included ideas for targeting clergy as well as lay congregational leaders, and found that clergy were open to combining resources from both religious and health-based institutions. Curriculum content included clergy desires for educational topics such as increasing their medical literacy and reviewing pastoral counseling approaches. Finally, clergy identified challenging barriers to EOL training needing to be openly discussed, including difficulties in collaborating with medical teams, surrounding issues of trust, the role of miracles, and caution of prognostication.

Conclusions

Future EOL training is desired and needed for community-based clergy. In partnering together, religious-medical training programs should consider curricula sensitive toward structure, desired content, and perceived clergy tensions.

INTRODUCTION

Seriously ill patients commonly exhibit religious and spiritual needs, particularly when approaching end of life (EOL) [1, 2]. Studies indicate the provision of spiritual support often influences patients’ medical decisions and utilization, as well as quality of life (QOL) at EOL [3]. Spiritual support provided by a patient’s medical team is associated with greater hospice utilization, less aggressive medical decisions, and better QOL at EOL [4]. Yet, medical teams infrequently provide spiritual support for patients with advanced illness [1, 5, 6]. Instead, many patients are already connected with religious communities, meaning that their communities address the spiritual needs of seriously-ill patients, especially those of ethnic/racial minorities [1, 5, 7, 8]. Some evidence suggests community clergy, while frequently discussing medically-related issues congregants face [8], recognize a need for better education in how to discuss the intersection of medical and theological concerns at the end of life with congregants [3, 9].

Prior studies suggest community clergy are not sufficiently trained in EOL care [3, 9–12]. Clergy indicate they hold a limited understanding of EOL medical knowledge [13] and desire further training on how to provide EOL spiritual care [14]. Despite a need for more comprehensive clergy EOL training, limited educational resources are available [15–17]. Unfortunately, none of these programs have been widely disseminated, and little literature is available concerning EOL training for clergy that considers in-depth clergy feedback.

In light of these research gaps, this study explores clergy perspectives obtained through in-depth, qualitative interviews on the concept of an EOL educational program for clergy. Little is known of clergy training within the intersection of health care, suggesting in-depth interviews as an initial manner to gather clergy viewpoints. As a qualitative study, the objective focused on clergy perceived educational needs including content, length, and format in learning to care for congregants facing EOL issues.

METHODS

This study is part of the larger National Clergy Project on End-of-Life Care, a mixed-method design including qualitative and quantitative interviewing of clergy (see also [3, 8, 9, 11, 18]). This project has been funded by the National Cancer Institute (#CA156732), the Issachar Fund, and Harvard’s Program on Integrative Knowledge and Human Flourishing. The study was approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Care Institutional Review Board. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Sample

The study used a purposive sample intended to represent a range of United States clergy perspectives, not the general U.S. population. The sample contains active clergy who were invited to participate based on a variety of pre-identified characteristics (i.e., race/ethnicity, gender, theological orientation, educational level, and religious denomination), which were hypothesized to be associated with more intensive medical utilization at EOL. As such, the sample is predominantly Christian and theologically conservative. The study also oversampled Asian, Black, and Hispanic clergy in order to include a strong racial/ethnic minority perspective. Data was collected through one-on-one interviews (n=14) and focus groups that brought together participants (n=21) in five U.S. states (California, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, and Texas). All participants provided informed consent per protocols approved by the Harvard/Dana-Farber Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

Protocol

A semi-structured interview guide and core set of open-ended questions were developed by an interdisciplinary panel of medical educators and religious experts. Study protocol details have been previously reported [3, 9, 11].

Qualitative Methodology

This study utilized triangulated analysis of multiple data sources and involved multidisciplinary perspectives (medicine, theology, education, psychology) to enhance validity, replicability, and transferability [19]. Two authors (S.E.K. and R.W.) independently analyzed all transcripts and identified themes and sub-themes using an editing style of analysis [20]; a final coding scheme was then created through a collaborative process of consensus with M.J.B. Authors S.E.K. and R.W. applied the finalized codes to all transcripts using NVivo (Mac v11.2, QSR International). A coding comparison issued a Kappa score of 0.72, following which coding discrepancies were resolved by consensus. A conceptual model emerged to illustrate the educational possibilities identified by interviewed clergy. All team members contributed to the final narrative and graphical representations.

RESULTS

Quantitative

Demographic information is provided in Table 2. Most were from Christian denominations. The study oversampled among non-White clergy (50%) in comparison to non-White clergy in the United States estimated at 15% [8].

Table 2.

Clergy Demographic Characteristics of Purposive Sample from Focus Groups and One-on-one Interviews, N=35.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Male Gender | 32 | 91.4 |

| Average Years Serving as Clergy (N = 32*) | 20 years | |

| Geographical Location | ||

| Northeast (Massachusetts and New York) | 11 | 31.4 |

| Southwest (Texas) | 11 | 31.4 |

| Midwest (Illinois) | 10 | 28.6 |

| West (California) | 3 | 8.6 |

| Race (N = 32) | ||

| White | 16 | 50.0 |

| Black | 14 | 43.7 |

| Asian | 2 | 6.3 |

| Ethnicity (N = 30) | ||

| Latino/Hispanic | 2 | 6.7 |

| Religious Tradition (N = 35) | ||

| Protestant1 | 27 | 77.1 |

| Roman Catholic | 4 | 11.4 |

| Eastern Orthodox | 1 | 2.9 |

| Jewish | 2 | 5.7 |

| Other (Center for Spiritual Living) | 1 | 2.9 |

| Theological Orientation (N = 32) | ||

| Theologically “Conservative”2 | 21 | 65.6 |

| Theologically “Liberal” | 11 | 34.4 |

| Educational Level (N = 34) | ||

| Below Master’s Degree | 6 | 17.7 |

| Master’s Degree (e.g. M.Div.) | 15 | 44.1 |

| Doctoral Degree | 13 | 38.2 |

| Desire future End of Life Training (N=29) | 21 | 72.4 |

Qualitative

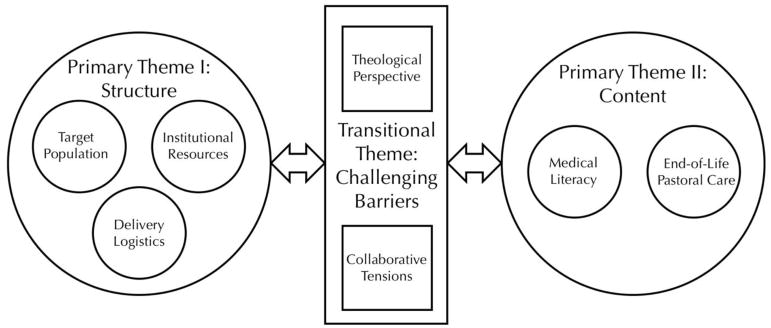

Thematic analysis of the qualitative data illustrates two primary themes connected by a transitional theme (see Figure 1). The first primary theme, “Structure,” focuses on structural components of the training and includes subthemes: 1) Target Population; 2) Institutional Resources; and 3) Delivery Logistics. The second primary theme, “Content,” explores potential content for the EOL educational program and contains subthemes: 1) Medical Literacy; and 2) Pastoral Counselling. These two primary themes are bridged by the transitional theme, “Challenging Barriers,” which considers the personal and systemic barriers that clergy experience around collaborating with medical teams. This transitional theme contains two subthemes: 1) Theological Perspective; and 2) Collaborative Tensions. Table 3 provides detailed definitions and representative quotes.

Figure 1.

Visual Representation of the Thematic Analysis

Table 3.

Summary of Themes

|

Primary Theme I: Structural Setup of the Training Program

| |

| Target Population | Clergy Interview Quotes |

|

| |

|

Who should attend the training?

Re: skill level, role (e.g., pastors, deacons, church volunteers, etc.), time in career, specialization, demographics |

“It really depends. Each clergy has a different background. Sometimes the person doesn’t have a scientific background. Sometimes they don’t understand all those things” (TC115).* |

|

Who does the training benefit/support? Re: impacted persons (e.g., congregation, etc.) |

“It would be more helpful in our congregational context to have a resource that would be useful for training lay visitors even more so than one additional type of training for the clergy” (MJB416-11). |

|

| |

| Institutional Resources | |

|

| |

|

What organizations could host and/or support the training program?

Re: Location and institutional partners (e.g., Harvard, seminaries, etc.) |

“I think it could be done through seminaries or even through some sort of coalition of the medical school with either a council of churches or a local seminary. There are also national chaplain associations, and maybe they need to get busier offering workshops and refresher courses” (CG124). |

|

What pre-existent programs and resources exist?

Re: Models to copy and/or programs with which to integrate the new training |

“In our Marriage Preparation Program, part of what we do is talk about what happens if a spouse dies” (CM1219). |

|

How can we find and contact participants?

Re: Organizations with which the target population is affiliated |

“So maybe it would look like first bringing information to pastors, either by pastoral associations or fellowships...” (JP414). |

|

| |

| Delivery Logistics | |

|

| |

|

When participating in the training program, what will it look like?

Re: Length and timing, form (e.g., in-person vs. online, etc.), available supplementary learning materials (e.g., videos, pamphlets), cost of program, teaching method (informational versus hands-on), language options, who teaches |

“I think that because of the nature of this, there can be a dual track. There can be some part presented by online video presentation, but it's practically impossible to do this kind of training without one- on-one or in group setting because the instructor has to be able to evaluate and monitor the developing skill set of the person who's learning how to do this. I don't think that can be done without being in the same room because there's so many nonverbal cues, bedside manner, emotional cues that need to be paid attention to, that you can't do on an online seminar, at least not in my experience” (RT0819). |

|

| |

| Primary Theme II: Content of the Training Program | |

|

| |

| Medical Literacy (Applied Knowledge) | |

|

| |

|

What medical knowledge do people want to learn?

Re: medical information, statistics, etc. |

“I think statistics are important. When we are faced with statistics I think those are good tools. We can say this is what the studies and statistics reveal; people who are diagnosed with this type of illness most of them die. I think those things could help us better understand what we are dealing with” (JP414). |

|

| |

| Pastoral Counselling (Practical Skills) | |

|

| |

|

What pastoral skills do people want to learn and practice through the training?

Re: Listening skills, counselling skills, patient decision making /advising, practical planning, pastoral, rituals (e.g., funerals) |

“I mentioned the word listening. I think listening is critical—in other words, gauging the situation. If you go into a dying person’s room, be that in a nursing home or a home, a house or a hospital, you need to be gauging the situation and that requires an ability to listen” (MB1030). |

| “You like to know in your region not just what, but who and where. I find that the family does a lot of that, but that's one of my frustrations. I'm not a strong enough resource for that kind of information–who to contact, what specifically they offer, just knowing very generally, but not in a specific way” (MB107). | |

|

| |

| Transitional Theme: Challenging Barriers | |

|

| |

| Theological Perspective | Clergy Interview Quotes |

|

| |

|

Through what theological perspective should the material be taught? Re: Point of view (e.g., through the Bible, a particular denomination, a secular/non-religious perspective, etc.), must pertain to the training specifically |

“As long as it is, let me put it this way, if it is from the biblical point of view, I would say 100% yes” (MB1021). |

| “If it is funded in any way by a specific religion, it has to have … a very strong mission of interfaith. And when I say "interfaith," I don't mean different strands of Christianity. A true interfaith training in this regard would have to be spiritual and not religious” (RT0819). | |

|

| |

| Collaborative Tensions | |

|

| |

|

What complexities arise in trying to balance faith and medicine?

Re: Theoretical understanding around non-alignment of faith and medicine, belief in miracles instead of medicine, meaning in/of death and dying, ethical situations that arise What challenges are experienced in working with medical professionals? Re: distrust of the medical system, desire/trepidation around collaborating with medical teams |

“I would love to get into the mind of a physician. […] What is the challenge facing a doctor when his or her patient dies? How challenging is it for a physician regarding bedside manner? So I can be a better collaborator with them. […] I think it is a worthwhile thing to do because we need to approach healthcare holistically. We are not just some machine. We also have a human side that needs to be addressed (TC1030).” |

| “I think you’ve got to bring it into balance. You are not a person who is faithless because you acknowledge that the doctor has said you have a terminal illness and you may not be here anymore... However, you now have to bring this into some kind of balance with your faith, and your God, and the people around you about what will happen. We live in tension of that. I’m a clergyman and I can’t solve those problems because I just don’t have enough wisdom to do that. I know how smart I am and how smart I’m not. And these questions are something that involves a lot. It involves community. It involves people. It involves the individual. It involves the medical community. I think if we come together you might get some clarity, not necessarily a solving, on these things. So that when you have an issue that comes up people can think much more in balance with what needs to happen versus one extreme or the other” (MB129). “They don't want to see a doctor at all because they say God is going to perform a miracle. So, that's a little bit confusing for us because we don't know what to say. We don't want to tell them, ‘You are wrong,’ because we believe that God still does miracles and God can. But as you are on this Earth, even you believe in miracles, but you have to see a doctor. If you don't, you cause a lot of confusion for some other people because sometime in the past people die because they don't go to see a doctor on time. As I'm talking to you now, I know some people like that” (MB1021). | |

Label indicates interviewer and interviewee allowing readers to assess the degree of variety of speakers in quotations.

Primary Theme I: Structure of the Training Curriculum

Target Population

Discussions of the target population thematically reflected two questions: 1) Who should attend the training? and 2) Who does the training impact?

The responses associated with the second question were fairly simple, with clergy generally referencing the positive impact for communities and congregations—especially the individuals affected by personal and/or familial EOL situations. However, responses associated with the first question were more complex. In discussing who should attend the educational program, clergy did not indicate EOL education is necessary for all community clergy; instead, they frequently used the phrase, “It depends…” followed by various criteria. In particular, clergy suggested it depends on skill level, educational background, career experience, and role played in one’s religious institution. It was mentioned that some clergy have poorer EOL pastoral skills and less EOL experience, and some pastors do not participate in EOL visiting but instead defer that role to deacons and lay-volunteers. However, in one focus group, when some participants vocalized support for primarily training deacons and church volunteers, other participants retorted that pastors should still be the focus:

Yes, we need to prepare our congregation and we need more lay people doing it, but in many places, it won’t happen until the pastor really is aware and has a heart for it. […] It starts with the pastor. If it doesn’t start with the pastor, then it really won’t go to the congregation (MJB416-4).

Institutional Resources

Clergy comments regarding institutional resources were associated with one of three thematic questions: 1) What organizations could host and/or support the training? 2) What pre-existent programs and resources exist? and 3) Through what organizations can participants be found and contacted?

When asked directly, there was a general consensus that Harvard—the host of this current study—would be an appropriate institution to host an EOL training for clergy: “Well, if Harvard did something like that I would be there” (MB107). However, many participants also put forth alternative suggestions. Some factors clergy considered important included the respectability of the institution and the presence of both a medical school and a seminary if hosted by an academic institution. A few participants also suggested the training could collaborate with local hospices and medical associations. Pre-existent programs that clergy mentioned include Marriage Preparation Programs, the National Bioethical Catholic Institute, One Month to Live, Stephen Ministry, as well as various local conferences, church forums, and hospital seminars. Clergy suggested reaching the target population through national pastoral associations and fellowships.

Delivery Logistics

Logistics of delivering the EOL training encompassed topics such as program length, time, and location; ideal teachers and teaching methods; and supplementary learning materials and language options. Combined, these topics generally answered the question: When participating in the training, what will it look like?

Ideal length and timing of the education varied by participant, with preferences ranging from three hours and others advocating for a two-day seminar. Most frequently clergy proposed a one-day program as a feasible option, especially if held on a Saturday, as it seemed a time best suited for many clergy. Multiple participants expressed that not having to travel to attend the educational program would be a major appeal. Several proposed an online-only program to eliminate travel; however, most advocated for in-person learning or a blended approach involving an in-person seminar with follow-up materials online. Regarding teachers, several participants specifically mentioned their interest in hearing from “experts,” stating that would be a big draw to attend: “To me, if the information is valuable and it’s from internationally known top experts, I'd give up a Saturday for that” (MB107). In addition, a general theme emerged in the data around the method of learning through stories. Clergy expressed particular interest in hearing educators’ personal experiences, watching and engaging in role-playing exercises, and having the opportunity to share and discuss their own experiences with other clergy. Clergy also requested the training provide supplemental learning materials, like pamphlets and booklets for later reference, and two participants expressed hope for Spanish resources.

Primary Theme II: Content of the Training

Medical Literacy

Within the subtheme of medical literacy, responses generally answered the question: What knowledge do clergy want to learn? Clergy expressed frustration at their lack of EOL knowledge and a desire to increase their medical literacy in order to better help congregants. In the words of one participant,

How do we better articulate this stuff, especially in light of where we are in healthcare today? I think we need to do something. Medicine is going so fast and people need to be able to make clear, concise and informed decisions (CM1219).

Specifically, clergy were interested in learning about medical statistics, current research, common medications and side effects, and the common stages of terminal illnesses:

The biggest lack I feel like I had when I came here and I'm still frustrated by, is understanding the medical side of it. I wish I knew more about cancer when I started; I wish I had some lectures on, ‘Okay, these are the types of cancers and these are the symptoms, these are the medications that they give and these are the side effects,’ so I could have a better understanding of the medical processes (MB107).

Pastoral Counselling

Discussions around pastoral counselling thematically reflect the question: What skills do clergy want to learn and practice? Despite pastoral counselling generally being taught in seminary and divinity schools, clergy conveyed an interest in further opportunities to learn and practice pastoral counselling skills, especially in an EOL context. They described the importance of listening, understanding grief, being a supportive presence for the family, and displaying appropriate bedside manners when visiting a dying person, which some referred to as “pastoral presence.” In addition, several participants discussed a tangentially related interest in learning how to help patients with EOL planning, advise them through medical decisions, and be a general source of knowledge on local medical resources.

Transitional Theme: Challenging Barriers

Although clergy were interviewed to help improve education, many of their responses insightfully focused on barriers to education. As such, analysis of the qualitative data suggests that even with an amenable training structure in place, the content will not be fully accessible or helpful for clergy unless certain personal and systemic barriers to EOL training are first addressed.

Theological Perspective

Many respondents thematically answered a question that could affect both the structure and content of the training—that is, through what theological perspective should the material be taught? One of the main ideas that emerged is summarized in the statement:

It depends on your faith tradition because they are all different. And some of them are different by just a little bit, but that little bit makes a huge difference. […] One size doesn’t fit all. So, if you are looking at making something, you’re not going to make something that is going to fit all. So, how do you look at specific faith traditions? (CM1219).

This idea that “one size doesn’t fit all” for clergy EOL training was reflected in many interviews, particularly when clergy shared their preferred theological perspective. In two separate interviews, clergy expressed interest in training based 100% on teachings in the Bible (JP414; MB1021). Several other clergy also advocated for a “biblical point of view” (JP414).

However, this was not shared by every interviewee. One advocated in the opposite direction, stating:

I would not be interested in attending any seminar that was based in a mainstream tradition, that was geared toward talking to people about concepts of heaven or hell, or moral obligation to extend life. If there was any of that in any such seminary, I would run in the opposite direction. [… But] if the seminary had a very strong bias in teaching clergy how to speak in an interfaith way and how to attend to the dying without preaching, and if they were able to teach clergy how to pray in a non-denominational, non-Christian, non-Jewish, non-specific way, I'd be highly inclined to attend and would be interested” (RT0819).

Nonetheless, most clergy were not as strongly opposed to a biblical-only perspective; rather, they hoped for a pluralistic approach. For instance, one clergy member stated, “We get so [absorbed] in our silos denominationally, traditionally. It’s helpful to sit with people from other traditions. Even in disagreement, it forces me to think about my own approach” (MJB416-1). While another said, “Well, realizing that death doesn't discriminate, I don't want to discriminate either. I think [the training] is something that all of us could use. Something that's practical [that] you could add your own faith and ideas to” (RT729).

Collaborative Tensions

Responses associated with this subtheme answered two questions: 1) What complexities arise in trying to balance faith and medicine? and 2) What challenges are experienced in working with medical professionals?

Trusting and collaborating with doctors was a particularly complex topic for participants. Some clergy expressed a strong desire for partnership with doctors. However, many clergy showed trepidation around collaborating with the medical field, as revealed through personal anecdotes of complex cases—many of which involved miracles. For some, this trepidation was based on a perceived conflict between medicine and personal religious values, as with one participant who admitted, “I have a little mistrust of the medical field sometimes” (CM1217), before providing a detailed story of a sick infant who recovered after a widely-performed Roman Catholic novena, concluding:

In beginning-of-life issues, sometimes the doctors scare young mothers: “Your child is going to be handicapped. You better have an abortion.” Many times, it is not true. Many times, the baby comes very well. They push fear and fear and fear. […] Who are we to judge that this handicap child should not be born? Oh, yes, we are wiser than God, right? I see sometimes people who lack faith can be the advocate of the devil, in that sense, and speak of putting fear in the families and creating a despairing attitude. So, we have to be careful. On the one hand, yes, we trust in a general sense. On the other hand, we need to have a discerning mind to see if what the doctor conforms to our values (CM1217).

Other clergy expressed that trepidation arose from the feeling that medical professionals are disinterested in working with clergy or do not value spiritual health. One participant even stated, “We’re a long way from an integrated approach with medicine and spiritual care for the benefit of the patient” (RT11142014).

The tension between faith and medicine also emerged during discussions on meaning in death and dying. There was some concern that medicine is becoming more technological and less human focused: “You don't want to lose the technology, but you don't want to lose the personal touch that's always been there” (RT729). In addition, there was significant discussion on the importance of human dignity at EOL and understanding death as part of the human experience. Much of this conversation focused on the current cultural fear of talking about death and dying. One interviewee indicated that funerals are now less commonly attended, while another said, “I think part of us—part of our humanness is—being lost because we are not dealing with the death we experienced early on in life as part of our life; we just push it aside” (CM1219). Still others advocated for more discussion around the meaning of death and dying:

What is dying? What is death? Is it an enemy? Or is it a friend? What is it? What do we understand death to be? And, how do we come to terms with it, because it is imminent if we live long enough. […] When you get a perspective of death you can also get a perspective of what life is about. So, I think as you start to shape your workshop themes, there can be a lot in that to discuss. How do we reconcile this whole thing about death and life, and what matters? (MB129).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to provide a framework for future EOL medical education programs targeting community clergy through synthesizing opinions on format, content, and perceived challenges. Issues around curriculum format (“Structure”) involve practical matters for clergy convenience and effectiveness, which are important but not difficult to solve. Table 4 summarizes practical questions and responses in how to potentially engage community clergy. However, we identified three critical challenges relating to content and tensions with the medical field that will demand further analysis and skillful deliberation.

Table 4.

Training Framework: Synthesized Clergy Ideas with Researcher Recommendations

| Who should attend the training? | Pastors should be the primary candidates, but additional openings could also be allowed for other ministers and lay-volunteers who visit the sick on behalf of the church. We recommend pastors of all experience levels and career lengths be encouraged to attend. |

| What organizations could host and/or support the training program? | A well-respected research institution holding both a medical and divinity school would be ideal in hosting a training program. Other health-religious partnerships should be pursued for co-hosting a collaborative program. |

| What pre-existent programs and resources exist? | A variety of programs could be useful for collaboration, including local hospices, medical associations, and Stephen Ministry (see Results for more suggestions). |

| How can we find and contact participants? | The training program could be advertised through national pastoral associations. We also recommend advertising in alumni letters from divinity schools and seminaries. |

| When participating in the training program, what will it look like? | A blended teaching approach including in-class instruction from professional experts followed by opportunities for online follow-up. Regarding the in-person learning, a one-day seminar—likely on a Saturday—would be ideal, especially if the program could be offered in a variety of locations to minimize travel time for participants. |

| What medical knowledge do people want to learn? | The training should include current, research-based information about common medications and side effects, stages of terminal illnesses, and mortality statistics for EOL illnesses. |

| What pastoral skills do people want to learn and practice through the training? | The training should also include opportunities for improving practical skills, including listening and counselling skills, as well as patient decision making and advising. |

| Through what theological perspective should the material be taught? | We recommend that the program be either interfaith or tradition-specific. The advantage of the interfaith approach is that university or secular hospital-settings may be more inclined to frame the training in a pluralistic perspective. The advantage of a denominational approach is that it will more likely reach clergy groups who are simultaneously traditional in their theology and suspicious toward pluralism. Tradition-specific approaches require a more complex partnership between particular denominations and health-based institutions. |

| What complexities arise in trying to balance faith and medicine? | We highly recommend the training program begin by addressing the complexity of balancing faith and medicine. This may be particularly effective if offered as an open discussion, especially on topics like miracles. It may also be helpful to provide information on a variety of ways people balance belief in miracles with medicine, as well as provide opportunities to consider and practice how to talk with congregants about miracles and death. |

| What challenges are experienced in working with medical professionals? | Similar to the faith and medicine approach, we recommend that early in the program, participants have the opportunity to discuss their concerns about working with medical professionals. It may also be helpful to have a medical professional come in to assuage any concerns and answer questions. |

The first issue is that EOL clergy education must be considered in terms of a partnership between religion and medicine. Within EOL matters, clergy must synthesize the religious values of their congregants as well as understand and weigh complex medical decisions [8]. An educational approach that does not uphold a collaborative balance between both sides will minimize either the complexity of the religious considerations, or insufficiently attend to the medical dimensions of EOL care (“Content”). While many clergy are eager to learn from and engage clinicians, there are also degrees of distrust and tension (“Challenging Barriers”) concerning how medicine marginalizes religious interpretations, such as the possibility of miracles. This suggests that physicians who identify with particular religious viewpoints may be the most effective educators, since they straddle both the spheres of religion and medicine [21, 22]. Inviting hospital chaplains to provide their perspectives may also help bridge the gap between religion and medicine. Clergy desire and need educational approaches that overcome issues of distrust with the medical system [8], but equally increase clergy competency in understanding the health conditions of their congregants [23]. This suggests that religious and medical communities must collaborate on a local level in order to grow organizational and individual relationships among clergy and clinicians.

Our findings also suggest that an educational partnership will seek a balance in religious and medical topics (“Content”). Most clergy expressed desire to understand the physician’s viewpoint better, especially to build trust and grow professional collaboration. Medical literacy includes increasing knowledge concerning disease trajectories, prognostication approaches, advanced care planning, options for palliative care and hospice, and understanding the implications of receiving aggressive medical treatments within terminal illness [9]. Clergy also suggested that case-based learning and opportunities for practice would be important components, especially when navigating nuanced discussions like praying for a miracle or whether to discontinue treatment or life-sustaining measures. Deepened understanding of and comfort level in handling EOL issues could empower clergy to engage more effectively with the medical team for the mutual goal of addressing and reconciling each individual patient’s particular spiritual and medical needs.

A third issue of tension involves weighing the benefits of an interfaith versus denominational approach to clergy EOL education. Clergy differ in their preferences, some desiring an interfaith approach focused on spirituality generally, and others a denominational approach centered within the particularities of a tradition-mediated perspective. Both approaches hold merit [11]. The interfaith approach is especially appealing for secular medical organizations who must consider a wide-range of pluralistic constituents. Nevertheless, EOL educators should equally consider a denominational framework tailored especially to clergy and lay leaders within Charismatic, Evangelical, Black, and Pentecostal traditions. These traditions are more likely to hold to religious values associated with more aggressive EOL care and limited EOL clergy-congregant discussions[8], which would deepen the urgency and clinical implications of engaging these groups. Clergy within this perspective are also more theologically conservative, and thus more suspicious of interfaith approaches [8, 11]. A religious-medical partnership is more likely to succeed if EOL education is tailored to theological values esteemed by those in attendance, and which are associated with clinically-relevant EOL outcomes. A potential strategy to incorporate both the interfaith and denominational frameworks is structuring a program that starts with a broad discussion on spiritual care for congregants at the EOL, and progresses to small group or breakout sessions focusing on specific faith traditions.

Encompassing a variety of theological, geographical, and racial perspectives, our qualitative design provides in-depth considerations for designing future clergy EOL training. However, it may not be generalizable outside American and Christian contexts.

CONCLUSION

This study provides in-depth interviews of clergy viewpoints around constructing a future EOL training curriculum at the intersection of religion and medicine. In addition to programmatic concerns of curriculum structure, clergy suggested the importance of increasing their medical literacy, equipping around pastoral care at the EOL, and addressing tensions and challenges associated with some collaborative distrust with clinicians and nuances in theological differences concerning the end of life.

Table 1.

Semi-Scripted Interview Guide Used for One-On-One Interviews and Focus Groups

| Do you think ministers/clergy need additional training in caring for patients who are facing life-threatening illness? We hope to create a new seminar for clergy in order to help them better care for patients who are facing life-threatening disease and end-of-life decisions. Given your many responsibilities and time-constraints, help us understand how the logistics of such a seminar would optimize your willingness to attend and learn. What might this training ideally look like that fits your needs? |

| [Interviewer to listen for ideas related to: a) Content, b) Length, c) Format (e.g., in-person or web-based), and d) university affiliated or particular seminaries, and ask prompts in those directions if necessary.] |

Acknowledgments

Funding: The study was made possible by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) #CA156732, the John Templeton Foundation, The Issachar Fund, and the Harvard Program on Integrative Knowledge and Human Flourishing.

Biographies

Dr. Michael Balboni is trained as a clergyman, holding a Master of Divinity and Master of Theology, and in the academic study of theology, obtaining a Ph.D. in practical theology from Boston University School of Theology. He has also received post-graduate training in qualitative and quantitative empirical methods through the Harvard School of Public Health and the University of Chicago. He is currently ranked as Instructor at Harvard Medical School through the Department of Psychiatry at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and is affiliated with Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s Department of Psycho-Social Oncology and Palliative Care. He has held this position for approximately six years as his first appointment. His research focuses on the intersection of spirituality and medicine, with particular focus on end-of-life care.

Dr. Balboni has overseen all facets of the material presented in this paper, as the principle investigator. The project was approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Care Institutional Review Board under his oversight. He takes responsibility for data collection, oversight of data analysis and interpretation, and senior authorship of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Sarah E. Koss, Harvard Divinity School, Cambridge, MA. Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA

Ross Weissman, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA. Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA

Vinca Chow, Department of Anesthesiology, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH

Patrick T. Smith, Harvard Medical School Center for Bioethics, Boston, MA. Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, S. Hamilton, MA

Bethany Slack, Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston, MA.

Vitaliy Voytenko, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL.

Tracy A. Balboni, Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA. Initiative on Health, Religion, and Spirituality within Harvard, Boston, MA

Michael J. Balboni, Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA. Initiative on Health, Religion, and Spirituality within Harvard, Boston, MA

Works Cited

- 1.Balboni TA, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):555–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcorn SR, et al. "If God wanted me yesterday, I wouldn't be here today": religious and spiritual themes in patients' experiences of advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(5):581–8. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders JJ, et al. Seeking and Accepting: U.S. Clergy Theological and Moral Perspectives Informing Decision Making at the End of Life. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(10):1059–1067. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balboni TA, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):445–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balboni TA, et al. Provision of spiritual support to patients with advanced cancer by religious communities and associations with medical care at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1109–17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balboni MJ, et al. Why is spiritual care infrequent at the end of life? Spiritual care perceptions among patients, nurses, and physicians and the role of training. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(4):461–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alcorn SR, et al. "If God wanted me yesterday, I wouldn't be here today": religious and spiritual themes in patients' experiences of advanced cancer. Journal of palliative medicine. 2010;13(5):581. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balboni MJ, et al. U.S. Clergy Religious Values and Relationships to End-of-Life Discussions and Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(6):999–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeBaron VT, et al. Clergy Views on a Good Versus a Poor Death: Ministry to the Terminally Ill. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(12):1000–7. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams ML, et al. How well trained are clergy in care of the dying patient and bereavement support? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32(1):44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeBaron VT, et al. How Community Clergy Provide Spiritual Care: Toward a Conceptual Framework for Clergy End-of-Life Education. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(4):673–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norris K, et al. Spiritual care at the end of life. Some clergy lack training in end-of-life care. Health Prog. 2004;85(4):34–9. 58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanders JJ, et al. “We have not done a good job preparing people to die”: U.S. Clergy Theological and Moral Perspectives Informing Cancer Decision-Making at the End of Life. in progress. [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeBaron VT, et al. How Community Clergy Provide Spiritual Care: Toward a Conceptual Framework for Clergy End-of-Life Education. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.<Duke EOL book.pdf>.

- 16.Abrams The Florida Clergy End-of-Life Education Enhancement Project - a description and evaluation. 2005 doi: 10.1177/104990910502200306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez E, et al. An educational program for spiritual care providers on end of life care in the critical care setting. J Interprof Care. 2011;25(5):375–7. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2011.573104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balboni MJ, et al. The Views of Clergy Regarding Ethical Controversies in Care at the End of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1999. p. xvii.p. 406. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phelps AC, et al. Addressing spirituality within the care of patients at the end of life: perspectives of patients with advanced cancer, oncologists, and oncology nurses. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2538–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balboni MJ, et al. "It depends": viewpoints of patients, physicians, and nurses on patient-practitioner prayer in the setting of advanced cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011;41(5):836–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saultz SPKaJ. Healthcare and Spirituality. Oxford, UK: Radcliffe Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]