Abstract

Carla Blauvelt and colleagues describe a multisectoral collaboration that enabled the scale up of a health advice telephone service and its transition to government in Malawi

The government of Malawi is working to improve timely access to accurate health information and services. Malawi’s health worker vacancy rate is 45%, exacerbated by a poorly distributed health workforce and limited training.1 Understaffing places strain on health workers and facilities, resulting in long waiting times and an average consultation time of two minutes.2 Additionally, inadequate quality of care, lack of privacy, and unfriendly health workers can deter people, especially adolescents, from accessing services.3

Many mobile health (mHealth) projects can positively impact the quality and coverage of care by increasing access to information and promoting changes in health behaviours.4 Despite mHealth being designated a priority by the World Health Organization, few such services have been implemented by governments in low income countries.5 In Malawi, over half of the population (54%) owns a mobile phone (86% urban, 48% rural; 52% of men, 33% of women).6 Additionally, phones are commonly shared within families and communities, making Malawi an ideal setting for an mHealth intervention.

Programme design

Chipatala Cha Pa Foni (CCPF)—Chichewa for “health centre by phone”—is a free health and nutrition hotline. Launched in 2011 as a pilot project in a rural district of Malawi, it is now available nationwide to anyone with access to an Airtel phone. Airtel is one of two major communications providers in Malawi, it is available in all districts and has over four million subscribers.7 A SIM card costs about $0.30 (£0.23; €0.26). CCPF originally focused on pregnancy, antenatal and postnatal advice, and advice for callers to seek facility care when appropriate. CCPF has since expanded to include all standard health topics—including water, sanitation, and hygiene; infectious diseases; and nutrition—in accordance with Malawi’s Ministry of Health (MoH) guidelines. Youth services were introduced, increasing access to sexual and reproductive health information for young people. The service has the flexibility to handle emergent problems, such as cholera outbreaks.

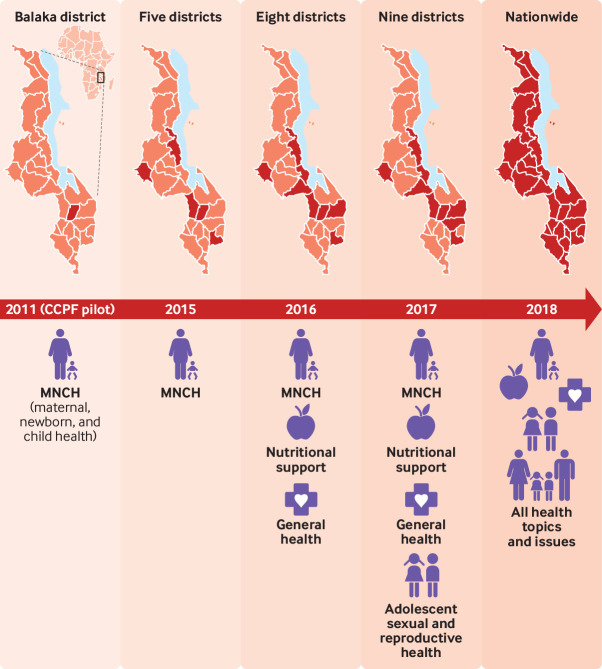

CCPF was developed iteratively by public, private, government, community, donor, and non-governmental stakeholders (fig 1). The non-governmental organisation (NGO) VillageReach is transitioning CCPF operations to the MoH, and the service will be promoted in every district in the country by the end of 2018. CCPF will be one of the first government run nationwide health hotlines in Africa when the handover is completed in 2019.

Fig 1.

Timeline map

The goal of CCPF is to improve health by increasing access to free, timely, quality health information and links to health facility services, thus extending the health system’s reach within communities. CCPF was designed to connect rural communities with the health system, as it is free and can be use by anyone through an Airtel phone (box 1).

Box 1. CCPF operations.

CCPF is a free service accessible to anyone using a mobile phone with an Airtel SIM, by dialling the shortcode number 54747.

From August 2018, the service operates 24 hours a day. The hotline takes live voice calls and also provides a tips and reminders service through text or audio messages. Callers can speak to a qualified nurse adviser for health information on all health topics or can register for the text or audio tips and reminders, or both.

Calls to hotline staff

Clients receive personal attention from hotline workers who speak all major Malawian languages and are trained extensively on various health topics. They use their professional judgment to refer callers to a nearby facility, if appropriate. There is no time limit for calls; the average duration is 15 minutes. Two CCPF doctors are available for more complex questions, but such call transfers are rare because most complex cases are referred to a health facility. Hotline supervisors conduct quality assurance reviews of call recordings to ensure quality.

Tips and reminders service

Currently there are three types of tips and reminders:

For pregnant women

For carers of children under one

For women of reproductive age (15 to 49 years)

A fourth is in development for adolescent boys and girls with a focus on sexual and reproductive health, including pregnancy, HIV, and prevention of sexually transmitted infections.

Tips and reminders messages can be received on both Airtel and non-Airtel phones, but users need to complete registration by speaking to hotline staff. It is a free, opt-in service and, once registered, a caller can choose to receive either text or voicemail messages, which are accessed through dialling the CCPF short code.

Pregnant women receive weekly tips and reminders that are gestation specific, whereas women of reproductive age get periodic reminders about sexual, reproductive, and maternal health. Carers of children under one year get reminders about general child health, such as vaccination schedules. All receive nutrition messages.

The messages are available in English, Chichewa (spoken by 70% of population), and Chiyao (spoken by 10%), and will be available in Chitumbuka (spoken by 10%) by December 2018.

Service delivery and impact

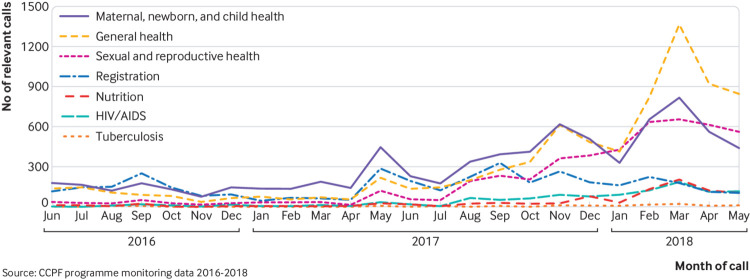

Since 2011, almost 58 000 people in Malawi have used CCPF, comprising 0.3% of the population and 1.4% of Airtel’s subscribers (table 1). Around 13 000 people have received tips and reminders, and 17 000 were referred to a health facility by hotline staff. The main purpose of calls diversified substantially between June 2016 and May 2018 (figs 2 and 3). CCPF is increasingly popular with adolescents (aged 15 to 19) and young adults (aged 20 to 24) as information targeted to their needs was added in August 2017 (supplementary file 1). These groups now represent 38% of all calls to the hotline. By mid 2017, the numbers of female and male clients had equalised; the age range of beneficiaries is now 0 to 80+ years.

Table 1.

CCPF calls and clients, 2011-18

| CCPF calls and clients | Maternal, newborn, and child health hotline | General health hotline | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July 2011 -May 2012 | June 2012 -May 2013 | June 2013 -May 2014 | June 2014 -May 2015 | June 2015 -May 2016 | June 2016 -May 2017a | June 2017 -May 2018 | ||

| Total No of calls* | 7100 | 6218 | 8599 | 11 698 | 10 831 | 5691 | 23 903 | 74 040 |

| No of relevant calls†,‡ (% of total calls) | 7100 | 5811 (93) | 7898 (92) | 10 153 (87) | 8990 (83) | 5473 (96) | 20 683 (87) | 66 108 (89) |

| Tips and reminders enrolments (% of relevant calls) | 2927 (41) | 2827 (45) | 3135 (37) | 5010 (43) | 3147 (35) | 1704 (31) | 5360 (26) | 12 980 (20) |

| Referrals (% of relevant calls) | 1092 (15) | 928 (16) | 1438 (18) | 1509 (15) | 1959 (22) | 2582 (47) | 7503 (36) | 17 011 (26) |

| Main purpose of call (% of relevant calls): | ||||||||

| Maternal, newborn, and child health (MNCH) | 7100 (100) | 5811 (100) | 7898 (100) | 10 153 (100) | 8990 (100) | 2046 (37) | 5490 (27) | 47 488 (72 |

| General health | — | — | — | — | — | 1149 (21) | 6564 (32) | 7713 (12) |

| Sexual and reproductive health§ | — | — | — | — | — | 464 (8) | 4392 (21) | 4856 (7) |

| Registration/tips and reminders | — | — | — | — | — | 1508 (28) | 2293 (11) | 3801 (6) |

| HIV/AIDS | — | — | — | — | — | 145 (3) | 1019 (5) | 1164 (2) |

| Nutrition | — | — | — | — | — | 127 (2) | 814 (4) | 941 (1) |

| Tuberculosis | — | — | — | — | — | 34 (1) | 111 (1) | 145 (0) |

| Estimated number of unique users¶: | 5493 | 4834 | 6987 | 9328 | 8946 | 4857 | 17 320 | 57 765 |

| % of total calls | 77 | 78 | 81 | 80 | 83 | 85 | 72 | 78 |

| % of Malawi population | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.3 |

| % of Airtel’s subscribers | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.4 |

Call volumes immediately before and after June 2016 are not strictly comparable as hotline software updated and monitoring definitions changed, leading to a recorded reduction in call volume immediately after the software upgrade

Relevant calls=total calls - (short dropped calls + irrelevant calls)

Before June 2016 this refers to non-dropped calls; since June 2016, this refers to calls that were not short dropped calls, irrelevant calls, or follow-up calls from clients who had been referred to a health facility.

Sexual and reproductive health was a topic of discussion for callers included in the calls regarding MNCH between June 2011 and May 2016, as MNCH served as the entry point to a broader discussion about women’s health. Non-MNCH calls were tracked by software and paper records from June 2016 and the new system allows MoH to track these topics separately.

Unique users recorded before June 2016 are not strictly cumulative to unique users recorded after June 2016 because of software upgrades and changes to the recording of unique clients.

Fig 2.

Diversification of the main purpose of call: June 2016 to May 2018

Fig 3.

Diversification of the main purpose of call: comparison of June 2016 and May 2018

By May 2018, more than 2000 calls were answered monthly by hotline workers (supplementary file 1), with numbers increasing as the service continued to expand to new districts. Approximately 20% of calls were made by using another person’s Airtel phone, showing that many people without an Airtel phone (or perhaps any phone) are accessing the service.

Users have been very satisfied with CCPF and appear to be recommending the service to friends and family in districts where no advertising has yet taken place (supplementary file 1). In 2016, a user satisfaction survey received feedback from 239 people (of 421 contacted; 57% response rate). Analysis revealed that there were extremely high levels of trust in the information given (98%), satisfaction with CCPF (99% “very satisfied”), and likelihood of recommending CCPF to someone else (95% “very likely”). Almost all users (93%) found the hotline easy to use, 75% learned something new by calling CCPF, 96% thought the hotline answered their questions completely, and 97% were “very comfortable” discussing sensitive health topics. A further evaluation of user satisfaction is under way in 2018.

An independent evaluation of the CCPF pilot phase found that CCPF was linked with improvements in knowledge about maternal and child health, and certain health behaviours.8 The evaluation found that CCPF was positively associated with:

Increased use of antenatal care within the first trimester

Increased use of a bed net during pregnancy and for children under five

Increased rates of early initiation of breastfeeding

Increased knowledge of healthy behaviours in pregnancy and postnatally.

CCPF connected nearly one fifth of the pilot phase population (women of childbearing age) to hotline workers. Those living further from health centres experienced a greater increase in knowledge of maternal, newborn, and child health practices, compared with those living close to health facilities.8 Qualitative data from focus groups revealed that CCPF was an easy-to-use service that saves time and delivers respectful, helpful advice while also empowering patients with information if they do seek care at a facility.8

Improved knowledge is important for preventive and health seeking behaviours, and although attribution of CCPF’s impact on health outcomes was not possible, the results of the pilot evaluation demonstrated CCPF’s potential to tackle health behaviour on a larger scale.

We developed this case study in order to understand the drivers of success in the development and growth of CCPF, which was selected from a global call from the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health (PMNCH) for proposals on success factors for multisectoral collaboration.9 A case study methods guide, developed by PMNCH, was used to ensure a standardised approach.10

Specific methods used for this case study included reviewing available data, interviewing key informants, producing a working paper, and holding a multi-stakeholder workshop to review the working paper and gather additional data and inputs (supplementary file 2).

Drivers of success in multisectoral collaboration to deliver CCPF

CCPF’s evolution from a community innovation in 2011 to nationwide reach in 2018 stems from the cooperation of the government, NGO, and private sector stakeholders (box 2), and the leadership and long term vision provided by government champions with VillageReach support (supplementary file 3). We identified four drivers of success underlying how partners worked across sectors to deliver sexual and reproductive health services for Malawians.

Box 2. CCPF stakeholders and funders.

The range of funders and stakeholders are detailed in supplementary file 3, and in chronological order, they are;

Ministry of Health (2011-present)

Concern Worldwide (2011-2016)

VillageReach (2011-present)

Baobab Health Trust (2011-present)

mHealth Alliance (2013-2015)

GSMA (2013-2015)

Clinton Health Access Initiative (2014-2015)

German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ) (2015-present)

Airtel (2015-present)

Johnson and Johnson (2015-present)

Vitol Foundation (2015-present)

Seattle International Foundation (2015-2016)

Project Concern International (2015-2017)

United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through the DREAMS Innovation Challenge (DREAMS) (2016-present)

USAID’s Organized Network of Services for Everyone’s (ONSE) Health Activity (2016-present)

A joint vision for government ownership

As one government stakeholder explained during our interviews, “The collaboration has worked smoothly and effectively because every stakeholder felt that the initiative is serving the same purpose.” This joint vision of creating a government run hotline to deliver health information to some of Malawi’s most remote communities unified the diverse group partners from inception, despite different institutional agendas (see supplementary file 3). While most agencies recognise the MoH as the primary provider of public health services, we found through the interviews that CCPF partners expressly prioritised the role of government from the beginning, identifying champions and building trust, and reflecting government priorities.

VillageReach collaborated with the technology organisation Baobab Health Trust to develop the free hotline and the tips and reminders message service, with MoH providing overall stewardship. VillageReach and Balaka’s District Health Management Team implemented the pilot, ensuring optimum integration of CCPF into existing health services and generating local MoH leadership. The close relationship with the District Health Management Team facilitated meaningful engagement with local stakeholders, ensuring that CCPF was designed for, and by, its users at community level. This was acknowledged as essential by interviewees.

More recently, Johnson and Johnson, which supports activities related to the transition to the MoH, funded a branding exercise that served two purposes. Firstly, it positioned the MoH as the most prominent and visible partner in CCPF’s external materials—crucial for expanding the service to new districts and communities. Secondly, it helped ensure that beneficiaries and stakeholders collaborated on a set of CCPF brand principles and design materials that reflect the benefits and valued elements of CCPF. Stakeholders noted this was a common challenge in multi-stakeholder initiatives with competing agendas and demand for partner brand visibility. Johnson and Johnson explained they had experience of undertaking branding exercises and trusted its potential to generate cohesion among different interested groups. Importantly, the government’s commitment to, and engagement with, CCPF has grown over time, and it is now primed to adopt operational responsibility in 2019.

Gradual expansion in scope and scale

During the multi-stakeholder workshop, partners agreed upon the importance of being able to deliver successfully on a smaller scale before expanding services and geographical scope from one to ultimately 28 districts (fig 1). The goals, resources, and expertise of a diverse group of partners helped extend CCPF from its initial maternal and child health focus to a broader range of health topics, making it relevant to a wider audience. The value of multiple partner organisations was reiterated in the stakeholder interviews; one CCPF funder said, for example, “Collaboration is absolutely critical—there is no one organisation that has the complete range of skills required to implement a programme like this on its own.”

Evidence from the CCPF pilot was crucial for cementing the relationship with the MoH at national level and attracted other partners and donors. A funder confirmed that, “Evidence was a standout thing for CCPF; it was one of the reasons CCPF was on our radar. There was a sense that CCPF was supporting the field at large. The evaluation was widely used to make the case.”

The German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ) motivated the addition of nutrition components to the hotline, and the US government saw the opportunity for CCPF to spread geographically and strengthen its adolescent sexual and reproductive health services. Support through the DREAMS initiative brought additional funding and expertise to add training, clinical modules, and community mobilisation for adolescent sexual and reproductive health and HIV/AIDS prevention. The adolescent sexual and reproductive health module was fully launched in August 2017 with corresponding district level community engagement activities (supplementary file 4). Although callers could already consult the hotline about sexual and reproductive health, substantial resources helped develop youth friendly health modules and extensively train hotline workers on these topics.

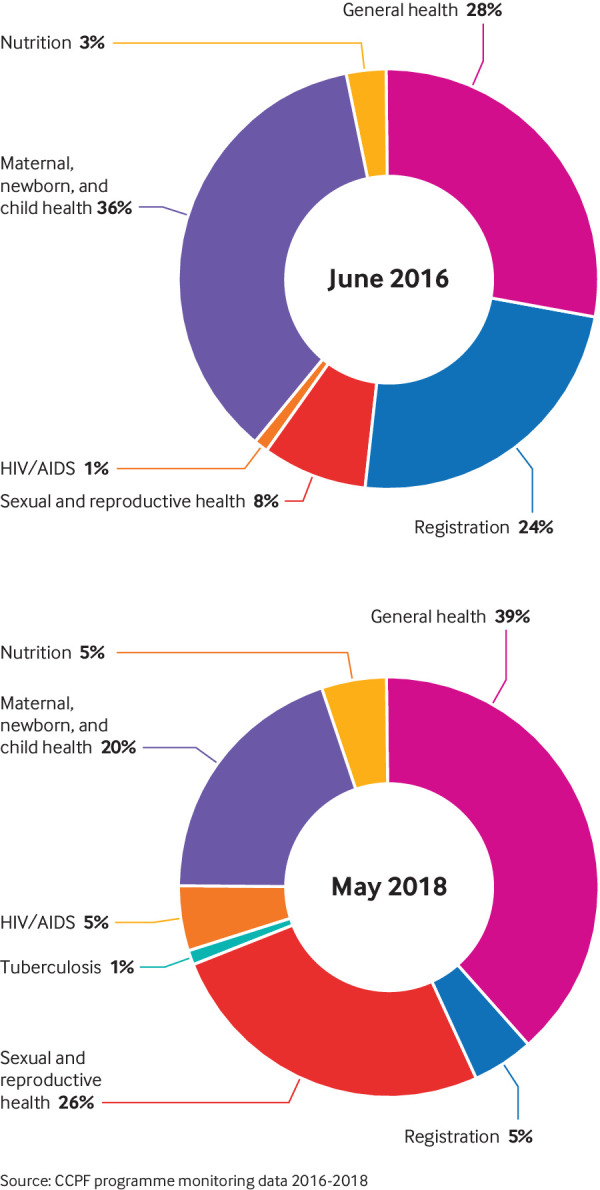

Collective resourcing and adaptability

Despite a number of partners throughout the life of CCPF, in the immediate post-pilot period VillageReach underwent several years (2011 to 2015) with few partners and invested its own resources to maintain the service. Since that period there has been considerable flexibility with roughly half of CCPF’s funding (fig 4), allowing resources to be strategically aligned with programme priorities. We found that the support and flexibility of partner funding had let CCPF adapt to patient demand. Increasing call volume regarding skin infections stimulated the development of clinical reference materials and training of hotline workers on this topic. Similarly, a rise in calls about non-communicable diseases motivated an in depth clinical training module. Key informants confirmed that despite having many partners and funders—which can introduce complexity—CCPF was able to strengthen and expand its services. As one MoH interviewee explained, “The involvement of many stakeholders did not cause any difficulty in collaboration; instead this offered an opportunity for collective improvement of CCPF.”

Fig 4.

CCPF budget and funding

Since the memorandum of understanding between VillageReach and Airtel was signed in 2015, the telecoms provider has covered all incoming call and promotional text costs. VillageReach, through donor support, pays the cost of outgoing follow-up calls to track patient referrals, as well as the airtime cost of the tips and reminders service—around 13% of the total budget (fig 4). With Airtel support, the investment needed for nationwide coverage in 2018 is approximately $365 000; this covers 27 hotline staff; training; supervision; monitoring and evaluation; quality assurance (supplementary file 5); data management and equipment purchases; outreach; and programme management.

The partnership with Airtel enabled government ownership to become a realistic prospect, given the constraints of Malawi’s national health budget. As one MoH interviewee said, “If the collaboration with private sector partners like Airtel did not exist, I doubt CCPF would still be there today.” Importantly, donors, the MoH, and partners have cooperatively funded CCPF, filling in funding gaps as they arise to sustain the hotline and improve its function and scope, without claiming ownership of, or credit for, its success.

Robust collaboration focused on sustainability

We found that CCPF’s partners had deliberately employed mechanisms to strengthen CCPF and build a sustainable programme (supplementary file 6). VillageReach leaders strove to foster strong MoH leadership and help place learning and adaptation at the centre of programme development and partner management. During CCPF’s inception period, VillageReach held co-creation workshops with the Balaka District Health Management Team to develop the pilot hotline content. Nurses from the district hospital supervised the hotline workers. CCPF’s developers created structures to share information, receive feedback, build trust, and generate informed ownership of the programme. The team consulted Malawi’s medical and nursing councils before and after the pilot to ensure ongoing conformity with national legislation, and both bodies are represented on the steering committee established for the transition. The partners prioritised community engagement throughout the design and implementation phases.

The MoH is stewarding CCPF through the transition period with strong engagement by ministry leadership. The MoH organises collective agreement and progress reviews through the steering committee (active since 2016), which was acknowledged by most stakeholders as a vital function for collaboration. One government employee said, “The establishment of the steering committee has helped, as most people regard themselves as part of this new initiative rather than just be spectators.” Several MoH departments and the Ministry of Finance have been involved in positioning CCPF as a national programme. A joint effort was needed to integrate CCPF into the Health Sector Strategic Plan II, for which negotiations are ongoing. Several stakeholders agreed that the CCPF technical adviser has been a key architect of these negotiations and the overall process of transition—which includes a thorough capacity checklist and the development of a transition toolkit to ensure that the correct skills and resources are in place before transfer of operations to the MoH. The adviser negotiates many competing priorities and represents the government while recognising the needs of multisector partners.

Reflecting on the integration of new partners, stakeholders recognised that partnerships took time to build and that third party brokers were helpful, especially in chartering new territories, such as collaborating with the private sector.

Several key informants explicitly valued VillageReach’s non-partisan role; one CCPF funder said, “VillageReach play as an honest broker between the government and private sector,” and a CCPF funder said, “VillageReach have been instrumental in being the bridge between us and the government and other stakeholders, playing that pivotal role in making sure that all relevant stakeholders are on the same page and aligned on objectives.”

Stakeholders expressly valued the fact that transparency was a key feature of the collaboration—for example, through an inclusive steering committee membership, monthly monitoring and evaluation reporting, regular stakeholder meetings, and open communication from VillageReach as the main implementers. A CCPF partner said, “Monthly stakeholder meetings have really helped, we’ve had the opportunity to recap, regroup, and be on same page.” A MoH interviewee said, “One of the reasons the process has worked so well is because of regular updates in the form of reports.”

Limitations and challenges

Several challenges face CCPF as it continues to grow and anticipates transition to the MoH.

Capacity v demand

CCPF has been operating a 24 hour service since August 2018; demand, however, is continuously increasing and callers now experience a long wait time. Neither the government nor VillageReach have funding to expand personnel at present. VillageReach and the MoH, with Johnson and Johnson’s funding, are, however, exploring technology enhancements while a caller waits on hold, among other ways to improve the service. Enhancements being considered are disease outbreak updates from the MoH, or the option to select recorded messages on a range of health topics while waiting or to use WhatsApp to catalogue and automatically respond to frequently asked questions. Despite increasing demand, however, the scale of coverage remains small (1.4% of Airtel’s subscribers) and increasing coverage will be a key priority for the MoH once CCPF transitions to government.

Measuring health outcomes

While hotline workers can provide health information about a range of topics and advise on prevention and treatment options, they cannot diagnose or treat over the phone. CCPF is primarily a health education and referral service and is not intended to replace health facility care. There are no current outcomes data to assess CCPF’s population level impact on health, although the evaluation started in summer 2018 will provide greater insights into equity and access to the hotline, user satisfaction, knowledge and behavioural changes, facility referrals, and quality of services.

Political support

Although the MoH provide strong leadership, the expansion in scope from an mHealth maternal, newborn, and child health initiative—and current transition to government ownership—means that not all departments have been as heavily involved since the onset of the programme. As one MoH stakeholder explained, this has “caused some delays to the transition which could have been shortened if we had engaged all departments from the start.” Further strengthening of collaboration is needed across sectors to ensure sustainability and funding once the MoH assumes ownership. Future partnerships and memorandums of understanding will be brokered directly by the MoH. Elections in Malawi and policy environment shifts may introduce changes within key government and civil service positions, risking the level of support for CCPF. To mitigate this, stakeholders are working to develop strong support for CCPF across political stakeholders, although some fear that CCPF’s success may be jeopardised by government ownership.

Financial model

Airtel’s partnership is essential for the sustainability of this free service, yet Airtel’s current exclusivity clause may preclude universal coverage. Airtel’s network currently spans 85% of Malawi’s land mass, but not all districts have strong coverage, leaving some communities without access to the hotline.

Equity in access

Just one third of women own a mobile phone, compared with half of men, and phone ownership increases with educational attainment and wealth.6 People in the Northern region are more likely to own a phone than their counterparts in the Southern and Central regions.6 Equity of access should be a priority future consideration, although inequity may be mitigated by the fact that 20% of calls to CCPF are made on a borrowed phone.

Case study methods

CCPF’s intersectoral collaboration was evaluated primarily by VillageReach staff, albeit in consultation with a wide range of stakeholders, and the multi-stakeholder review workshop was not well attended across all sectors (MoH, NGO, and donor stakeholders, as well as CCPF beneficiaries, contributed to the workshop). Thus, certain perspectives may be missing from this analysis.

Conclusion

After only seven years, an NGO operated district maternal, newborn, and child health programme is poised to become one of Africa’s first nationwide, government run general health hotlines. New partnerships have been transparently coordinated while the programme adapted to include additional stakeholders. A common goal of sustainable government ownership helped build bridges across different programme agendas and beyond the health sector.

CCPF has advised almost 60 000 Malawians on nutrition, health promotion, illness prevention, health seeking behaviours, and sensitive matters such as sexual and reproductive health, through a convenient and free to use system. Although substantial investment is required to strengthen the health system and increase the health workforce, CCPF supplements the health system and gives clients more information than could be imparted during the short consultations that are common in Malawi. CCPF’s programme model is applicable to other countries and environments, as it could be adapted easily for another context outside Malawi. For example, the immediacy of access to health information and good quality health advice by phone has great potential for resilience building in fragile settings.

A recent WHO report5 recognising the significant role of digital technologies in health system strengthening noted the need to tackle both the lack of multisectoral collaborations between government ministries, departments, and donor agencies; and the lack of a process for taking pilot projects to scale. The CCPF partners have tackled both of these challenges. We demonstrate how complementary and mutually reinforcing cooperation across sectors can increase equitable access to health information for people who are traditionally underserved because of geographical, social, or literacy barriers. Under government ownership, CCPF is primed to achieve lasting benefits.

Key messages.

Chipatala Cha Pa Foni (CCPF) aims to improve health outcomes by increasing access to free, timely, high quality health information and referral to health services, extending the reach of the health system to underserved communities

CCPF stems from cooperation of government, NGO, and private sector stakeholders, coupled with leadership and long term vision provided by government champions

Collaboration mechanisms included strong alignment for stewardship by Malawi’s Ministry of Health, and a priority on working meaningfully with government to ensure smooth integration and long term sustainability

CCPF will be one of the first government run nationwide health hotlines in Africa when the handover to the Ministry of Health is completed in 2019

Acknowledgments

We thank all CCPF collaborators, past and present, and extend their gratitude to those who have participated in this case study process, including; Benson John (M&E Specialist VillageReach Malawi), Beverly Bhima (Malawi Health Equity Network), Chifuniro Katsabola (CCPF hotline nurse), Emily Bancroft (president, VillageReach, Seattle), Esther Kondowe (Ministry of Health), Fanny Kachale (RHD, MoH), Flera Chimango Kulemero (United Purpose), George Tambala (CCPF hotline nurse), Harold Kumadzi (CCPF community beneficiary), Joanne Peter (Johnson and Johnson), Jessica Crawford (director and group lead Health Systems, VillageReach, Seattle), Lindi Van Niekerl (LSHTM and Malawi College of Medicine), Nedson Fosiko (Clinical Services Department MoH), Norah Chavula (Airtel), Omega Sambo (CCPF programme officer), Patience Tchongwe (CCPF hotline supervisor), Samuel Gamah (community health officer), Vitowe Batch (GIZ), and Zaito Jangoya (CCPF Community Beneficiary). The authors thank Rudi Thetard (ONSE) and Zachariah Jezman (mHealth technical adviser seconded by VillageReach to ONSE, under the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) for participating in qualitative data collection and the multi-stakeholder review meeting, respectively.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by the authors

Supplement 1: file one

Supplement 2:Methods for developing the case study

Supplement 3: Stakeholders

Supplement 4: Community engagement

Supplement 5: Quality assurance

Supplement 6: Table of collaborative mechanisms and architecture

See www.bmj.com/multisectoral-collaboration for other articles in the series.

Contributors and sources: CB and CA wrote the case study report, with input from LM, MW, UK, and HN. Literature was reviewed by CA. Key informant interviews and additional data collection were undertaken by CA, HN, UK, and MW. Analyses of monitoring data and presentation of results were conducted by LM. Supervision and critical appraisal of evidence were provided by ID, CA, CB, MW, and AK. CA drafted the case study paper and coordinated the drafting process, while all authors undertook critical revisions of the manuscript drafts including rewriting. CB is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work except the funding from PMNCH at the WHO as part of the case study series, to conduct data collection, synthesis, and write-up of the case study. Although authors are paid employees of their respective companies, no other financial relationships with organisations exist that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of WHO, USAID, or the US government.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a series proposed by the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health hosted by the World Health Organization and commissioned by The BMJ, which peer reviewed, edited, and made the decision to publish the article. Open access fees for the series are funded by PMNCH.

References

- 1.Government of the Republic of Malawi. Malawi health sector strategic plan II (2017-2022) towards universal health coverage. 2017. www.health.gov.mw/index.php/policies-strategies?download=47:hssp-ii-final.

- 2. Jafry MA, Jenny AM, Lubinga SJ, et al. Examination of patient flow in a rural health center in Malawi. BMC Res Notes 2016;9:363. 10.1186/s13104-016-2144-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Machira K, Palamuleni M. Women’s perspectives on quality of maternal health care services in Malawi. Int J Womens Health 2018;10:25-34. 10.2147/IJWH.S144426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001362. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. mHealth: use of appropriate digital technologies for public health. March 2018. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA71/A71_20-en.pdf.

- 6.National Statistical Office, The DHS Program, ICF International. Malawi demographic and health survey 2015-16. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR319/FR319.pdf.

- 7.National Statistical Office of Malawi & MACRA. Survey on access and usage of ICT services in Malawi: the 2014 report. www.macra.org.mw/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Survey_on-_Access_and_Usage_of_ICT_Services_2014_Report.pdf.

- 8.Invest in Knowledge Initiative. Evaluation of the information and communications technology for maternal, newborn and child health project. Balaka District 2013. www.villagereach.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/ICT_for_MNCH_Report_131211md_FINAL.pdf.

- 9.Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health. What works and why? Success factors for collaborating across sectors for improved women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health. www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/case-studies/en/index3.html.

- 10.Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health. Methods guide for country case studies on successful collaboration across sectors for health and sustainable development. 2018. www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/case-study-methods-guide.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement 1: file one

Supplement 2:Methods for developing the case study

Supplement 3: Stakeholders

Supplement 4: Community engagement

Supplement 5: Quality assurance

Supplement 6: Table of collaborative mechanisms and architecture