Abstract.

Entamoeba histolytica is a protozoan parasite that causes amebiasis and poses a significant health risk for populations in endemic areas. The molecular mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis and regulation of the parasite are not well characterized. We aimed to identify and quantify the differentially abundant membrane proteins by comparing the membrane proteins of virulent and avirulent variants of E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS, and to investigate the potential associations among the differentially abundant membrane proteins. We performed quantitative proteomics analysis using isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation labeling, in combination with two mass spectrometry instruments, that is, nano-liquid chromatography (nanoLC)-matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry and nanoLC-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Overall, 37 membrane proteins were found to be differentially abundant, whereby 19 and 18 membrane proteins of the virulent variant of E. histolytica increased and decreased in abundance, respectively. Proteins that were differentially abundant include Rho family GTPase, calreticulin, a 70-kDa heat shock protein, and hypothetical proteins. Analysis by Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships database revealed that the differentially abundant membrane proteins were mainly involved in catalytic activities (29.7%) and metabolic processes (32.4%). Differentially abundant membrane proteins that were found to be involved mainly in the catalytic activities and the metabolic processes were highlighted together with their putative roles in relation to the virulence. Further investigations should be performed to elucidate the roles of these proteins in E. histolytica pathogenesis.

Introduction

Entamoeba histolytica is an enteric protozoan parasite that causes amebiasis in human and nonhuman primates. The invasive trophozoites of E. histolytica are capable to inhabit host tissues and provoke diseases such as intestinal colitis and liver abscess. However, the molecular mechanism and pathogenesis of amebiasis need further investigations. Entamoeba histolytica strains have been reported to exhibit different degrees of virulence, resulting in various clinical symptoms in patients.1 Several amebic virulence determinants have been characterized, such as galactose/N-acetyl galactosamine-inhibitable lectin (Gal/GalNAc lectin), cysteine proteases (CPs), amebapore, and phagosome-associated proteins. Galactose/N-acetyl galactosamine-inhibitable lectin was reported to be responsible for the adherence of trophozoites to host cells, cytolysis, parasite invasion, and phagocytosis.1–3 Cysteine proteases have been implicated in cytopathic activities such as damage of host cells and host tissue, induction of intestinal inflammation, and digestion of some components of the extracellular matrix.4,5 Phagosome-associated proteins such as EhRac A, EhPAK (p21-activated serine/threonine protein kinase), and actin have been reported to be involved in endocytosis and disease pathogenesis.6

Membrane surface is the first outer layer where the trophozoites and host cell come into contact. The adherence of trophozoites to the host cells, which is mediated by Gal/GalNAc lectin, is an important step for the disease development. Furthermore, cell–cell adhesion is initiated by cell adhesion molecules, which are also members of integral membrane proteins.7 Membrane proteins have transmembrane (TM) domains and/or signal peptides to facilitate the biological functions of the organism. For instance, TM domain-containing proteins are responsible for cellular recognition and adhesion, molecular receptors, substrate transportation through membranes, signal transduction, protein secretion, and enzymatic activity.8 Meanwhile, signal peptides are responsible for leading the arrangement of proteins into cellular organelles or cell membrane.9 The important functions exhibited by the TM domains and signal peptides suggested that membrane proteins play essential roles in membrane trafficking and vesicular trafficking machinery in relation to the expression of virulence factors of E. histolytica. This can be related to a study by Nozaki and Nakada-Tsukui in 200610 in which membrane protein candidates including CPs and amebapores were found to be responsible for cytopathic activities during phagocytosis. Other membrane-associated proteins such as small GTPase and Rab proteins also play important roles in membrane trafficking because they serve as molecular switches that coordinate the sequential vesicle fusion with target membranes during phagosome maturation.11

The single-cell E. histolytica lacks rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus. However, similar to other eukaryotic cells, it contains the essential components that encode the basic vesicular transport system.12,13 This system, which comprises membrane-associated proteins, plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of amebiasis, although the transportation of pathogenic factors or virulence determinants into the host remains unknown. According to the findings by Biller et al.,14 the plasma membrane of E. histolytica is greatly interconnected and persistently exchanges with the intracellular membrane systems; thus, proteins may be present in the extracellular system without any hint of their plasma membrane association. To date, the numbers of in-depth studies of membrane proteomes of E. histolytica are limited, and there are still many E. histolytica hypothetical proteins that remain unknown. In this study, we performed differential membrane protein abundance profiling analysis between virulent (vEh) and avirulent (avEh) variants of E. histolytica (HM-1:IMSS) to further understand their functions and interactions. Because virulence varies among strains, we restricted this comparison to E. histolytica strain HM-1:IMSS.

Material and Methods

Ethics statement.

All experiments involving animals were strictly performed according to the Mexican Law for the Production, Care, and Use of Laboratory animals (NOM-062-ZOO-1999). All animal procedures were performed under the protocol number 091-2016, approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering.

Entamoeba histolytica (HM-1:IMSS) amebic culture.

Axenic cultures of the vEh and avEh E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS trophozoites were maintained in TYI-S-33 medium according to standard protocols by Diamond et al.15 Trophozoites were harvested after 72 hours and washed with phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2. A total of 1 × 107 parasites were aliquoted into each tube and immediately lyophilized. The virulence of the vEh trophozoites was maintained by periodically recovering them from amebic liver abscess of infected hamsters according to the protocol from Olivos et al.16 Meanwhile, the avEh trophozoites were vEh trophozoites that lost the ability to cause amebic liver abscess because of the long-term in vitro maintenance of the culture (> 18 years).16,17

Membrane protein extraction.

The membrane proteins of vEh and avEh trophozoites were extracted using the ProteoExtract™ Native Membrane Protein Extraction kit (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The separated cytosolic fraction from the membrane fraction was kept for further analysis. The extracted vEh and avEh membrane proteins were each subjected to acetone precipitation by adding six times volume of 100% ice-cold acetone to the protein sample, then vortexed, and incubated at −20°C for 4 hours. The precipitated protein was redissolved in 100 µL of dissolution buffer (pH 8.5, 0.5 M triethylammonium bicarbonate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) before isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ®) labeling. The amount of extracted membrane protein was determined using RCDC assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The absorbance of the protein sample was read at 750 nm, using a NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE).

To assess the extracted membrane protein profile, 40 µg each of vEh and avEh membrane proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE using the Mini-PROTEAN® electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) for 90 minutes at 100 V. The gel was washed using water with gentle agitation for 5 minutes, for three times. Subsequently, overnight staining was performed using RAMA stain (containing 0.05% Coomassie brilliant blue R250, 10% acetic acid, 15% methanol, and 3% ammonium sulfate). The gel was destained with water until the protein bands were clearly visible.

Protein digestion and iTRAQ labeling.

Duplex iTRAQ analysis was performed using two isobaric tags (114 and 117). Hundred microgram each of vEh and avEh membrane proteins was treated with 1 µL denaturant (2% SDS), followed by adding 2 µL reducing reagent (50mM tris-[2-carboxyethyl] phosphine), and then incubated at 60°C for 1 hour. The reduced cysteine residues were alkylated with cysteine blocking reagent (200 mM methyl methanethiosulfonate [MMTS] in isopropanol) at room temperature for 10 minutes. The protein samples were then digested by adding 10 µL trypsin solution and incubated at 37°C for 12–16 hours. The digested peptides were labeled with iTRAQ reagent (AB Sciex, Foster City, CA) at room temperature for 1 hour, whereby the avEh and vEh peptides were labeled with 114 and 117 isobaric tags, respectively. Finally, the labeled peptides of avEh and vEh were pooled into a tube. Cation exchange was then performed using ICAT Cation Exchange hardware and ICAT Cation Exchange Buffer Pack (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) by following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Nano-liquid chromatography coupling MALDI-MS/MS analysis.

Peptides separation was performed using a NanoLC-2D Ultra system (Eksigent, Sprockhövel, Germany) connected to an automated Eksigent EKSpot MALDI spotter (Eksigent). In the tray of the autosampler, 5 µL of peptide sample was first auto-loaded and packed into a ProteCol C18 trap column (internal diameter: 300 µm; length: 50 mm; pore size: 300 Å; and particle size: 3 µm). Mobile phase buffer A (2% acetonitrile [ACN], 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid [TFA]) and buffer B (98% ACN, 0.1% TFA) were used during reversed phase gradient elution. The flow profile for gradient elution of peptides was set with 20–80% of acetonitrile for a duration of 165 minutes and a flow rate of 300 nL/minutes. The eluted peptide fractions were spotted directly on the 384-well MALDI plate, with a concentration of 5 mg/mL α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) continuously being added to the column effluent via a mixing tee piece at a flow rate of 1.8 µL/minute, from the 55th to the 135th minute of the gradient phase. The chromatogram was recorded at a wavelength of 214 nm by using a SONNTEK UV detector 2500 (SONNTEK, Upper Saddle River, NJ).

Tandem mass spectrometry analysis was performed using a MALDI-TOF/TOF™ 5800 system (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA). MS spectra were acquired between m/z range 800 and 4,000, and the precursor ion selections were set by accumulating up to 500 laser shots per spectrum. Signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio was set at a minimum of 10, and spots with most intense precursor ions were subjected to tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis. Mass spectrometry spectra were acquired with a maximum of 10 precursors, by accumulating up to 2000 laser shots per spectrum, and set to a minimum ratio of 15 S/N. External calibration of mass spectra was performed using calibration mixture 1 from AB Sciex. Five technical runs were performed on every biological replicate to ensure the result consistency of the protein identification.

Nano-liquid chromatography coupling electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) analysis.

The analysis was performed at the Protein and Proteomics Centre, National University of Singapore. Briefly, peptide separation was performed using nanoLC Ultra and ChiPLC-nanoflex (Eksigent, Dublin, CA) in trap-elute configuration. The samples were first loaded on a 200-μm × 0.5-mm column (ChromXP C18-CL, 3 μm) and eluted on an analytical 75-μm × 15-cm column (ChromXP C18-CL, 3 μm). Mobile phase A (2% ACN and 0.1% formic acid) and mobile phase B (98% ACN and 0.1% formic acid) were used for peptide separation at a flow rate of 0.3 μL/minutes. The gradient elution was set as follows: 5–5% of mobile phase B in 1 minute, 5–12% of mobile phase B in 19 minutes, 12–30% of mobile phase B in 120 minutes, 30–70% of mobile phase B in 10 minutes, 70–90% of mobile phase B in 2 minutes, 90–90% in 7 minutes, 90–5% in 6 minutes, and held at 5% of mobile phase B for 10 minutes.

Tandem mass spectrometry analysis was performed using 5600 TripleTOF systems (AB SCIEX, Concord, ON). Mass spectrometry (MS) spectra were acquired between m/z range 400 and 1,800, and the precursor ion selections were set at accumulation times of 250 ms per spectrum. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed on the 20 most intense precursor ions, with an accumulation time of 100 ms per cycle, with 15 seconds dynamic exclusion. The MS/MS was acquired in the high-sensitivity mode using rolling collision energy.

Database search, criteria, and parameters.

Protein identification analysis for the iTRAQ experiment was executed using ProteinPilot™ software version 4.5 (AB SCIEX). Paragon algorithm was used as the default program to search against AmoebaDB version 4.1 database (accessed October 15, 2017) and common Repository of Adventitious Proteins (cRAP) for peptide identification and isoform-specific quantification. The cRAP includes the possible contaminant proteins in this study such as bovine serum albumin and keratin (http://www.thegpm.org/crap/). For protein identification, a strict cutoff was applied to minimize false-positive results. Proteins with unused ProtScore ≥ 1.3 (confidence interval of 95%) and at least two peptides with 95% confidence were used as the identification criterion. Bias correction was also applied to the resulting data set to minimize any discrepancies conveyed because of the unequal mixing when the differently labeled samples were pooled. For iTRAQ quantification analysis, Pro Group algorithm automatically selects the peptide for quantification with the criterion of at least two peptides with 99% confidence, for the reporter peak area, error factor, and P-value calculations. The false discovery rate was set at < 1%, while a detected protein threshold of > 0.47 (confidence interval of 66%) and a competitor error margin of 2.00 were applied.

In Paragon algorithm configuration, parameters were set as follows: digestion: trypsin; cysteine alkylation: MMTS; instrument: TOF/TOF 5800 (for MALDI) and TripleTOF 5600 (for ESI); search effort: thorough; ID focus: biological modifications; false detection rate (FDR) analysis: yes; background correction: yes; bias correction: yes. The measurement used in ProteinPilot was derived from the 95% confidence interval (error factor) and calculated from the standard deviation in logspace.

For the selection of differentially abundant proteins, we considered the following criteria: 1) the proteins must contain at least two unique peptides (at least 95% confidence) and 2) the proteins must have P < 0.05 and the proteins identified with mass tag changes ratio must be > 2. A protein that was detected in two replicates by either LC-MALDI-MS/MS or LC-ESI-MS/MS was regarded as significant.

Cytosolic fraction.

In-solution digestion of the proteins in the cytosolic fraction was performed by following the method published by Ujang et al. (2016).18 The digested samples were analyzed via LC-ESI-MS/MS at Proteomics Core Facility, Malaysia Genome Institute, National Institutes of Biotechnology Malaysia. The peptides were separated using the Dionex UltiMate™ 3000 RSLCnano (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) nano-liquid chromatography system, and the MS analysis was performed using an Orbitrap Fusion™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) mass spectrometer. To achieve spatial discrimination of the peptides, they were packed into and eluted with EASY-Spray Column PepMap® RSLC, C18, 2 µm particle size, 50 µm id × 150 mm coupled with pre-column (µ-Precolumn PepMap 100, C18, 3 µm particle size, 300 µm id × 5 mm) at a flow rate of 0.3 µL/minutes with mobile phases A (deionized distilled water with 0.1% formic acid) and B (ACN with 0.1% formic acid). The elution gradient of the sample was set for 101 minutes with a gradient of mobile phase B, 5–95% for 93 minutes, 95% for 2 minutes, and then to 5% in 2 minutes. For MS analysis, the instrument was set in the data-dependent mode. The parameters for the full scan spectra were as follows: a scan range of 310–1,800 m/z, a resolving power of 120,000, an AGC target of 4.0e5 (400,000), and a maximum injection time of 50 ms. The method consisted of 3 seconds at the top speed mode where precursors were selected for a maximum of a 3-second cycle. Only precursors with an assigned monoisotopic m/z and a charge state of 2–7 were further analyzed for MS/MS. All precursors were filtered using a 20-second dynamic exclusion window and an intensity threshold of 5,000. The MS/MS spectra were analyzed using the following parameters: a rapid scan rate with a resolving power of 60,000, an AGC target of 1.0e2 (100), 1.6 m/z isolation window, and a maximum injection time of 250 ms. Precursors were fragmented by collision-induced dissociation and higher-energy collisional dissociation at a normalized collision energy of 30% and 28%, respectively. Data analysis and database matching against AmoebaDB version 4.1 and cRAP were performed using Proteome Discoverer™ software version 2.1 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The parameters used in the analysis were fixed modifications: carbamidomethylation (C), variable modification: oxidation (M), deamidation of asparagine (N) and glutamine (Q), maximum missed cleavage set at two, FDR < 0.1%, and parent mass and precursor mass tolerance at 10 ppm and 0.6 Da, respectively. The significant score (−10 lgP) for protein acceptance was set at > 20, whereas the minimum unique peptide was set at one.

Gene ontology, membrane protein prediction, and protein–protein interaction prediction.

The differentially abundant proteins were subjected to bioinformatics analysis using the Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships (PANTHER) DB classification system (http://www.pantherdb.org/) (accessed April 6, 2017), to identify their subcellular localization, molecular function, or biological process.

To assess the quality of the experiment, the predictions of membrane protein topology on the proteins were analyzed using a bioinformatics tool, TOPCONS (http://topcons.cbr.su.se/) (accessed April 6, 2017). A protein was considered as a membrane protein if it contained TM helix and/or signal peptide.

The protein–protein interaction prediction was performed using STRING software (version 10.5) (https://string-db.org/) (accessed March 13, 2018) to summarize the network of predicted protein interactions. The association in the protein–protein interaction network predicted by STRING covered either direct physical binding or indirect interaction, for example, involvement in the same metabolic pathway or cellular process. The network analysis of differentially abundant membrane proteins of the vEh variant of E. histolytica was performed separately, presented by the confidence view. The protein network under the confidence view which showed stronger associations was represented by thicker lines.

Radar plot was created with the differentially abundant proteins using Microsoft Excel to allow a clear depiction of the differentially abundant proteins with various fold changes.

Results

Protein identification.

In total, 1,307 proteins were identified from both biological replicates, where 194 and 1,113 proteins were identified by LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF and LC-ESI-MS/MS, respectively (Figure 1A). A total of 41.2% and 41.5% membrane proteins were predicted from the total proteins identified from LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF and LC-ESI-MS/MS, respectively (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Venn diagram indicating the two sets of proteins that were analyzed independently by LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF and LC-ESI-MS/MS. (B) Membrane protein prediction using TOPCONS on the total identified proteins analyzed by LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF and LC-ESI-MS/MS. LC-ESI-MS/MS = liquid chromatography coupling electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry.

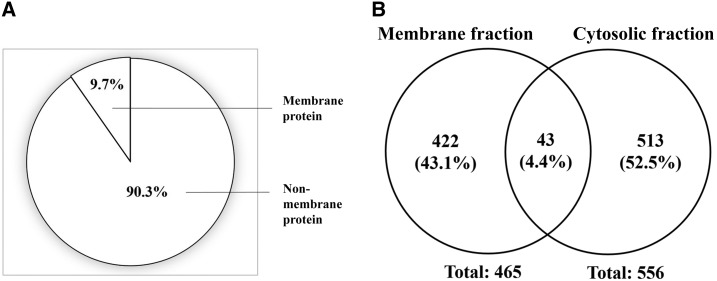

Cytosolic fraction.

To assess the specificity of the membrane extraction method in this experiment, the membrane protein prediction was performed by TOPCONS on the proteins identified from the cytosolic fraction (Figure 2A). A total of 556 proteins were identified from the cytosolic fraction by LC-ESI-MS/MS. TOPCONS predicted 54 of 556 (9.7%) of identified proteins were regarded as membrane proteins (Supplemental Information). The Venn diagram revealed that there were 43 proteins (4.4%) commonly detected in both membrane and cytosolic fractions (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Membrane protein prediction using TOPCONS on total protein identified from cytosolic fraction. (B) Venn diagram indicating the comparison of total identified proteins from membrane fraction and cytosolic fraction.

Differentially abundant proteins.

In total, by combining the results from both mass spectrometer analyses, 75 differentially abundant proteins (36 increased and 39 decreased abundance) fulfilled our filtering criterion in the vEh versus avEh variants. When membrane protein prediction analysis was applied to all the identified differentially abundant proteins, there were 19 increased and 18 decreased proteins that were predicted as membrane proteins (Figure 3A and B). We also compared the identified differentially abundant proteins across both the biological replicates. There were three (30.0%) and 12 (16.9%) proteins commonly identified by LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF (Figure 3C) and LC-ESI-MS/MS, respectively (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

(A) Membrane protein prediction using TOPCONS on the differentially abundant proteins that exhibit ≥ 2-fold changes in virulent versus avirulent variants. (B) Differentially abundant membrane proteins identified by LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF and LC-ESI-MS/MS. M1 and M2 represent two replicates detected from LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF and E1 and E2 represent two replicates detected from LC-ESI-MS/MS. (C) Differentially abundant membrane proteins identified by LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF in two technical replicates represented by M1 and M2. (D) Differentially abundant membrane proteins identified by LC-ESI-MS/MS in two technical replicates represented by E1 and E2.

The complete details of the analyses of differentially abundant proteins including membrane protein prediction, gene ontology functional classification, and protein–protein interaction prediction analysis are provided in the Supplemental Information.

Virulent versus avEh membrane proteins with increased abundance.

The combination of differentially abundant membrane proteins identified by both mass spectrometers revealed that 19 membrane proteins were identified with increased abundance in the vEh versus avEh variants (Table 1). The top five increased membrane proteins that exhibited the highest fold change were the hypothetical protein (4.7-fold); NAD(P) transhydrogenase subunit alpha, putative (4.4-fold); calreticulin (4.3-fold); beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase, beta subunit (4.2-fold); and dipeptidyl peptidase, putative (4.0-fold). Radar plot was used to represent the massive number of the increased membrane proteins with different fold changes in a clear visualization (Figure 4A).

Table 1.

List of identified increased abundance membrane proteins with fold change ≥ 2 in virulent versus avirulent variants

| No | Accession number | Protein name | Peptides (95%) | % Cov | iTRAQ ratio (117:114) | Detected by* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EHI_007330 | Beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase, beta subunit | 23 | 36.6 | 2.109 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 1 | EHI_007330 | Beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase, beta subunit | 25 | 35.6 | 4.169 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 2 | EHI_007930 | Hypothetical protein | 14 | 38.3 | 2.070 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 3 | EHI_010710 | Hypothetical protein | 13 | 30.3 | 4.699 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 4 | EHI_014030 | NAD(P) transhydrogenase subunit alpha, putative | 43 | 25.0 | 4.406 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 5 | EHI_015380 | Immuno-dominant variable surface antigen | 40 | 39.7 | 2.606 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 6 | EHI_059830 | Hypothetical protein | 31 | 31.9 | 2.399 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 7 | EHI_065330 | Gal/GalNAc lectin subunit Igl2 | 95 | 58.0 | 2.089 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 8 | EHI_068090 | Serine carboxypeptidase (S28) family protein | 15 | 28.7 | 2.377 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 9 | EHI_069560 | Hypothetical protein | 25 | 55.1 | 2.512 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 10 | EHI_097630 | Phospholipase B, putative | 19 | 39.1 | 2.109 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 11 | EHI_100320 | Multidrug resistance protein, putative | 34 | 18.4 | 2.489 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 12 | EHI_120590 | Hypothetical protein | 24 | 31.5 | 2.780 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 12 | EHI_120590 | Hypothetical protein | 19 | 23.0 | 3.467 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 13 | EHI_126310 | Rho family GTPase | 5 | 29.7 | 3.467 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 14 | EHI_133900 | Galactose-inhibitable lectin 170-kDa subunit, putative | 143 | 58.4 | 2.399 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 15 | EHI_136160 | Calreticulin, putative | 5 | 20.6 | 2.655 | LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF-1 |

| 15 | EHI_136160 | Calreticulin, putative | 7 | 38.1 | 3.221 | LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF-1 |

| 15 | EHI_136160 | Calreticulin, putative | 6 | 24.9 | 3.767 | LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF-2 |

| 15 | EHI_136160 | Calreticulin, putative | 12 | 32.4 | 4.325 | LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF-2 |

| 16 | EHI_136440 | Dipeptidyl peptidase, putative | 14 | 26.5 | 4.018 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 17 | EHI_149860 | Hypothetical protein T24C12.3, putative | 11 | 21.6 | 2.089 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 18 | EHI_161040 | Hypothetical protein | 16 | 60.6 | 2.355 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 19 | EHI_182720 | Dipeptidyl peptidase, putative | 25 | 40.4 | 3.192 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

Gal/GalNAc lectin = galactose/N-acetyl galactosamine inhibitable lectin; iTRAQ = Isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation; LC-ESI-MS/MS = liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry.

Note: Detection in replicate 1 or 2 is represented by “1” or “2” after the name of MS; Peptides (95%) indicates the number of distinct peptides having at least 95% confidence; % Cov (coverage) indicates the percentage of matching amino acids from identified peptides having confidence greater than 0 divided by the total number of amino acids in the sequence.

Figure 4.

Radar plot of increased abundance (A) and decreased abundance (B) membrane proteins in virulent versus avirulent variants.

Functional analysis of the membrane proteins with increased abundance.

The proteins with increased abundance in vEh variants were involved in molecular functions such as catalytic activity (eight proteins), binding (three proteins), signal transducer activity (one protein), and transporter activity (one protein) (Figure 5A). These proteins were involved in biological processes such as metabolic process (nine proteins), cellular process (three proteins), cellular component organization or biogenesis (one protein), biological regulation (one protein), and response to stimulus (one protein) (Figure 5B). These proteins were classified into six protein classes, which included hydrolase (six proteins), enzyme modulator (one protein), transporter (one protein), calcium-binding protein (one protein), transferase (one protein), and oxidoreductase (one protein), as shown in Figure 5C.

Figure 5.

Pie chart representation of the Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships functional classification of increased abundance membrane proteins in virulent versus avirulent variants according to their molecular function (A), biological process (B), and protein class (C) involvement.

Virulent versus avEh membrane proteins with decreased abundance.

A total of 18 proteins with decreased abundance were identified in vEh variants when compared with the avEh variant by using both the mass spectrometers (Table 2). The top five decreased membrane proteins that exhibited the highest fold change were thioredoxin, putative (4.8-fold); hypothetical protein, conserved (4.8-fold); hypothetical protein (3.9-fold); long-chain fatty-acid CoA ligase, putative (3.6-fold); and hypothetical protein (3.4-fold). These proteins were represented in the radar plot as shown in Figure 4B.

Table 2.

List of identified decreased abundance membrane proteins with fold change ≥ 2 in virulent versus avirulent variants

| No | Accession number | Protein name | Peptides (95%) | % Cov | iTRAQ ratio (117:114) | Detected by* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EHI_001100 | Hypothetical protein | 11 | 29.4 | 0.488 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 2 | EHI_017000 | Hypothetical protein | 26 | 36.8 | 0.483 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 3 | EHI_021560 | Thioredoxin, putative | 37 | 47.8 | 0.207 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 3 | EHI_021560 | Thioredoxin, putative | 31 | 59.6 | 0.483 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 4 | EHI_022130 | Hypothetical protein, conserved | 12 | 17.0 | 0.387 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 5 | EHI_025090 | Long-chain fatty-acid CoA ligase, putative | 22 | 28.5 | 0.275 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 5 | EHI_025090 | Long-chain fatty-acid CoA ligase, putative | 26 | 28.8 | 0.308 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 6 | EHI_057700 | Hypothetical protein, conserved | 8 | 10.0 | 0.209 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 7 | EHI_077500 | Galactose-specific adhesin 170-kD subunit | 9 | 12.8 | 0.406 | LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF-1 |

| 8 | EHI_093970 | Hypothetical protein | 42 | 53.5 | 0.483 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 9 | EHI_111990 | CXXC-rich protein | 19 | 17.2 | 0.457 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 10 | EHI_114140 | Hypothetical protein | 4 | 39.0 | 0.319 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 11 | EHI_117690 | Hypothetical protein | 14 | 65.9 | 0.413 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 12 | EHI_128100 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase, putative | 12 | 55.2 | 0.461 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 13 | EHI_138080 | Hypothetical protein | 12 | 52.2 | 0.294 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 14 | EHI_148990 | Heat shock protein 70, putative | 15 | 23.3 | 0.409 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 15 | EHI_160980 | Hypothetical protein | 15 | 33.9 | 0.258 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-1 |

| 16 | EHI_163540 | Estradiol 17-beta-dehydrogenase, putative | 11 | 21.9 | 0.413 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 17 | EHI_182530 | Hypothetical protein | 5 | 46.1 | 0.353 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

| 18 | EHI_199590 | 70-kDa heat shock protein, putative | 10 | 26.9 | 0.366 | LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF-2 |

| 18 | EHI_199590 | 70-kDa heat shock protein, putative | 130 | 61.7 | 0.466 | LC-ESI-MS/MS-2 |

iTRAQ = isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation; LC-ESI-MS/MS = liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry.

Note: Detection in replicate 1 or 2 is represented by “1” or “2” after the name of MS; Peptides (95%) indicates the number of distinct peptides having at least 95% confidence; % Cov (Coverage) indicates the percentage of matching amino acids from identified peptides having confidence greater than 0 divided by the total number of amino acids in the sequence.

Functional analysis of the membrane proteins with decreased abundance.

The membrane proteins with decreased abundance in vEh variants are involved in substantial molecular functions such as catalytic activity (three proteins), binding (one protein), signal transducer activity (one protein), and transporter activity (one protein), as shown in Figure 6A. These proteins are also involved in biological processes including metabolic process (three proteins), cellular process (two proteins), localization (two proteins), response to stimulus (two proteins), biological regulation (two proteins), and cellular component organization or biogenesis (one protein) (Figure 6B). These proteins are assigned into five protein classes, which comprise the transfer/carrier protein (one protein), oxidoreductase (one proteins), hydrolase (one protein), ligase (one protein), and membrane traffic protein (one protein), as shown in Figure 6C.

Figure 6.

Pie chart representation of the Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships functional classification of decreased abundance membrane proteins in virulent versus avirulent variants according to their molecular function (A), biological process (B), and protein class (C) involvement.

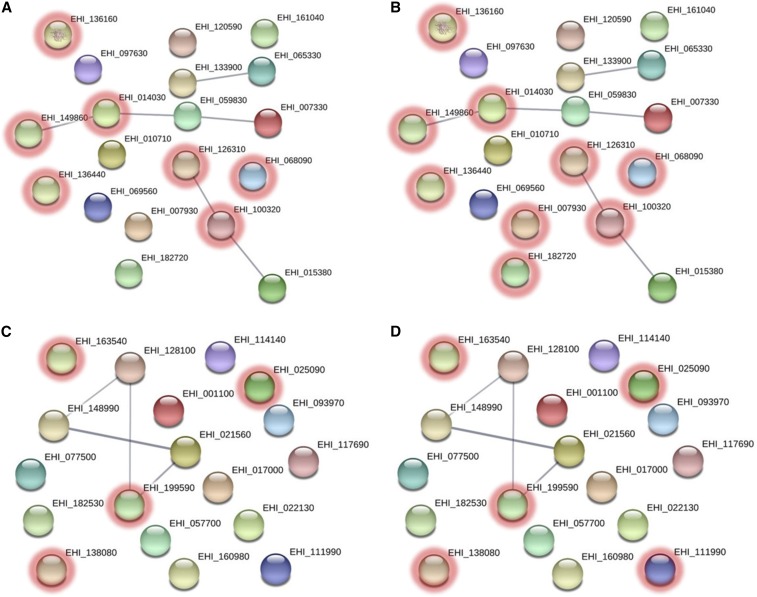

Protein–protein interaction prediction among differentially abundant membrane proteins.

Membrane proteins with increased abundance that are involved in the catalytic activity and metabolic process are shown in Figure 7A and B, respectively, whereas membrane proteins with decreased abundance that are involved in the catalytic activity and metabolic process are shown in Figure 7C and D, respectively. The details of the STRING analyses are tabulated in Supplemental Information.

Figure 7.

Interaction network of differentially abundant membrane proteins generated with STRING. Nodes highlighted with red rings represent increased abundance membrane proteins involved in (A) molecular function and (B) biological process and decreased abundance membrane proteins involved in (C) molecular function and (D) biological process according to gene ontology analysis via Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Discussion

In this study, the applications of two kinds of mass spectrometers enhanced the proteome coverage and generated complementary results. The analyzer systems in both mass spectrometers were configured to function with their own acquisition modes and, hence, maximize the number of precursors interrogated. Therefore, unique proteins can be obtained when different mass spectrometer systems were combined. This was proven when proteins were uniquely detected by either LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF or LC-ESI-MS/MS (Figure 2). For example, calreticulin (EHI_136160) and Ras family GTPase (EHI_058090) were unique proteins detected solely by LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF and LC-ESI-MS/MS, respectively. A previous study by Bodnar et al. using shotgun analysis also showed that the combination of different ionization techniques improved the proteome coverage and maximized the number of peptide fragmentation spectra.19

The pathogenic strain of E. histolytica HM1:IMSS is known as a causative agent of amebiasis, where they express their pathogenicity by invasion and ability to lyse the epithelial tissues of the host. But the reasons or conditions responsible for human pathogenicity have remained enigmatic. Several proteomic comparison studies have been performed to compare the proteomes among E. histolytica strains and Entamoeba species.20,21 This is because the genetic variations exhibited by different species, strains, and variants could influence the gene and protein expression.22 To narrow down the minute variation between variants in the pathogenic strains, this study provided an indepth understanding on the comparison of proteome profiles between vEh and avEh variants of a single strain.

The putative roles in virulence of the membrane proteins with increased abundance in the vEh variant.

Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships DB analysis demonstrated that most of the membrane proteins with increased abundance were involved in the catalytic activity (molecular functions) and metabolic process (biological process), as highlighted in Figure 7. The proteins include Rho family GTPase (EHI_126310), NAD(P) transhydrogenase subunit alpha (EHI_014030), multidrug resistance (MDR) protein (EHI_100320), calreticulin (EHI_136160), beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase, beta subunit (EHI_007330), serine carboxypeptidase (EHI_068090), dipeptidyl peptidase (EHI_136440, EHI_182720), and uncharacterized protein (EHI_149860). These membrane proteins with increased abundance may play specific roles in contributing to E. histolytica virulence.

Rho family GTPase is a member of G protein and is responsible for the regulation of actin organization, cytoskeleton dynamics, cell cycle, and gene expression of E. histolytica.23 The overexpressed Rho family GTPase genes have been reported to play an important role in the adaptation of trophozoites to the host’s intestinal environment by altering their cytoskeleton-mediated processes.24 Therefore, we postulate that the increased abundance of this protein in the vEh variant may play a role in sustaining the adaptation proficiency of trophozoites in the host, hence increasing the chance of successful colonization and invasion. This scenario also concurred with a previous study which indicated that the adaptation of E. histolytica to the host intestinal environment was attended by the increased subset of the cell signaling genes including the TM kinases, Ras and Rho family GTPases, and calcium-binding proteins.25

NAD(P) transhydrogenase subunit alpha, putative is responsible for molecular functions including binding and catalytic activity, and biological processes including cellular process, localization, and metabolic process. This integral membrane protein is involved in the proton transport of hydride ions reversibly between nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate across the membrane, for the synthesis of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate hydrogen, glutathione reduction, and regulation of flux through the tricarboxylic acid cycle.26 This protein (alternately known as pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase) was previously detected in the phagosomes of E. histolytica during phagocytosis.27 Apart from that, an increased expression of the gene-encoding protein NAD(P) transhydrogenase subunit alpha, putative was also observed in the E. histolytica Rahman strain after contact with human mucus compared with Rahman in the in vitro culture.25 Hence, we hypothesize that the increased abundance of NAD(P) transhydrogenase in the vEh variant may indicate a higher potential of phagocytosis than that by the avEh variant.

Multidrug resistance protein is a stress response protein that is involved in TM transport and responsible for the ATP binding and ATPase activity. The transcriptomic regulation of the phenotype of MDR in E. histolytica has been proven to be regulated by the P-glycoprotein (Pgp) (EhPgp1 and EhPgp5) genes and these genes have been shown to participate in the MDR in E. histolytica, leading to an ATP-dependent efflux.28–31 This is because the MDR is mediated by the overexpression of genes encoding Pgps, whereby Pgp functions as a multidrug efflux pump which is capable to discharge drugs out of the cell.32–34 In this case, we hypothesize that the increased abundance of MDR protein in the vEh variant of E. histolytica may indicate that it could induce an efflux response even without the presence of drugs.

Calreticulin is a calcium-binding protein that is located mostly in the ER,35 which has a role in binding and metabolic processes. The increased abundance of calreticulin observed in this study was also seen at the gene expression level, whereby the gene-encoding E. histolytica calreticulin demonstrated an overexpression in the vEh trophozoites during the development of experimentally induced amebic liver abscess in hamsters.36 It was reported to engage in the initial stage of the host–parasite relationship as this protein triggered an immunogenic response in the human host, mainly in amebic liver abscess patients.37 In addition, ameba developed an evasion mechanism against the host immune responses, by expressing the ER-associated calreticulin, which inhibited the classical serum complement pathway.38 This showed that calreticulin may play a significant role in the host–parasite relationship during the early infection phases.38 Therefore, we postulate that the increased abundance of calreticulin in the vEh variant of E. histolytica may indicate its involvement in the regulatory mechanism in relation to pathogenesis between the host and the parasite to ensure its successful survival in the host.

Beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase, beta subunit is a glycosidase which is involved in hydrolysis and mainly takes part in glycolysis. It has been postulated by researchers that this protein might participate with supplementary components and induce the carbohydrate meshwork damaging of intestinal epithelial lining, facilitating the parasite invasion.39 The association of glycosidase and mucus depletion that caused intestinal disruption was also reported, where gene-encoded beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase and beta-galactosidase in the vEh strain were found to be upregulated during the colon invasion.25 This consequence is also supported by previous findings where glycosidase activity diminished the intestinal mucin in E. histolytica.40 Therefore, the increased abundance of beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase protein, shown in the present study, may support the invasive behavior of the vEh variant during the intestinal invasion.

Serine carboxypeptidase is classified under the S28 serine peptidase family. This protein was also found in the uropods proteome of E. histolytica.14 The potential biological function and mode of action of this particular protein in relation to virulence have not been reported and specifically characterized. However, the serine peptidase from Entamoeba invadens has been postulated to play a significant role in the encystation process.41 Fortunately, Makioka et al. in 2009 demonstrated the involvement of serine protease in the E. invadens excystation and metacystic development using inhibitors specific for serine proteases.42 The protease activity of serine proteases from the S28, S9, and S26 families was inhibited in the cyst lysates by phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride. Their findings indicated that the participation of Entamoeba serine proteases in the excystation and metacystic development was related to pathogenicity.

Dipeptidyl peptidase is from the lipase family which is categorized under the clans of serine peptidase. Dipeptidyl peptidase was previously detected in the isolated uropod extruded fractions when E. histolytica trophozoites were exposed to the serum of amebiasis patients.43 This enzyme is involved in lipid metabolism such as hydrolysis of triglycerides, phospholipids, and cholesterol esters.44 At the gene-expression level, the gene encoding E. histolytica dipeptidyl peptidase demonstrated the highest level of expression among all serine peptidases,45 although the actual role of this enzyme in contributing to the E. histolytica pathogenicity still remains unclear. On the other hand, the involvement of dipeptidyl peptidase IV of Giardia in encystation during Giardia differentiation in an in vitro model was confirmed.46 The increased abundance of dipeptidyl peptidase in the vEh variant of E. histolytica may not directly contribute to the virulence factor, but the discovery of this protein in the uropod of E. histolytica provides an enlightening information as several components of the uropod such as Gal/GalNAc lectin may trigger immune responses against E. histolytica from the hosts.43 Therefore, further investigation of the function of this enzyme will be needed.

Hypothetical protein (EHI_149860) was predicted as a glycosylase that is involved in the hydrolase activity which acts on the glycosyl bonds. This protein was also involved in several metabolic pathways including the pyrimidine metabolism and glycosaminoglycan degradation based on information available in the AmoebaDB database. Based on Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART) sequence analysis, the intrinsic feature of this protein consists of a TM region between 7 and 29 amino acid residues, two low complexity regions between 2 and 27 amino acid residues, and 93–207 amino acid residues. This protein was also found in the purified uropod fractions from trophozoites.43 However, we are unable to postulate the potential role of this protein in relation to virulence and pathogenicity because of the limited information. Hence, further investigations are needed to identify its potential role as E. histolytica virulence factor.

The putative roles in virulence of the membrane proteins with decreased abundance.

On the other hand, the membrane proteins with decreased abundance were also mainly involved in the catalytic activity (molecular functions) and metabolic process (biological process) including the 70-kDa heat shock protein (HSP) (EHI_199590), long-chain fatty-acid CoA ligase (EHI_025090), B-keto acyl reductase (EHI_163540), CXXC-rich protein (EHI_111990), and uncharacterized protein (EHI_138080).

The decreased abundance of 70-kDa heat shock protein in the membrane of the vEh variant was interesting as this may provide an insight into the nature of this protein in the vEh strain (HM-1:IMSS). Heat shock protein is a stress response protein toward heat; when there is a sudden increase in temperature, HSP is synthesized and activated to protect the ameba.47 In this study, the decreased abundance of 70-kDa HSP in the membrane of the vEh variant probably showed that the trophozoites were under a stress-free condition in the culture. The decreased abundance of 70-kDa HSP was also observed in glucose-starved trophozoites,48 which may indicate that only certain stresses activate the HSP to induce a protective response. Under hyperoxia conditions, high transcriptional level of HSP genes in the vEh strain (HM-1:IMSS) was observed when compared with the non-vEh strain, and this was correlated with a high protein level of HSP70.17 The discrepancy in our results compared with the previous study by Santos et al. could also be because of the fact that they analyzed the total lysates of vEh and non-vEh E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS strains under hyperoxia conditions, whereas we only analyzed the membrane fractions of cultured amebae.17 The HSP70 is necessary for amebic virulence such as in the formation of amebic liver abscess in hamsters.17 Furthermore, the presence of these HSPs in the membrane fraction can be linked with the involvement of HSP70 in facilitating chaperones, intracellular protein transportation, and secretion functions.49

Long-chain fatty-acid CoA ligase is an enzyme that is responsible mainly for the ligase activity and is involved in the lipid metabolic processes. Under a glucose-starved condition, the trophozoites of E. histolytica showed a remarkably reduced abundance in the proteins associated with metabolism, particularly in the fatty acid pathway.48 In a normal E. histolytica pyruvate-to-ethanol pathway, acetyl-CoA is converted to acetaldehyde and then reduced to ethanol.50 But the decreased level of the long-chain fatty-acid CoA ligase under the glucose-starved condition may be significant, whereby acetyl-CoA was shifted from the fatty acid pathway into the pyruvate-to-ethanol pathway,51 to deliver an alternative energy source for sustaining the survival of trophozoites. By referring to the reported statements,50,51 we speculate that the decreased abundance of this protein in the vEh variant may have been associated with the E. histolytica virulence by altering the fatty acid pathway to increase their susceptibility toward stresses during glucose starvation.

Beta-ketoacyl reductase, also alternately known as estradiol 17-beta-dehydrogenase, is an oxidoreductase that is responsible for the oxidoreductase activity and is involved in the lipid metabolic process. This protein was previously found in the phagosome proteome52 and uropod fractions43 of E. histolytica. Beta-ketoacyl reductase is one of the proteins involved in the elongation of long-chain fatty acids, and catalyzes the reduction of β-ketoacyl-CoA to L-β-hydroxyacyl CoA.53 In this present study, the decreased abundance of this protein in the vEh variant of E. histolytica may be linked to the downregulation of long-chain fatty-acid CoA ligase as both are involved in the lipid metabolism. The correlation of the function of this protein with virulence is unclear. However, we postulate the decreased abundance of the beta-ketoacyl reductase could attempt to reduce the lipid metabolic processes to minimize energy usage.

CXXC-rich protein has a signal peptide and seven furin-like cysteine-rich regions that are found in a wide range of proteins and is involved in signal transduction via receptors tyrosine kinase.54 The association between Gal-GalNAc lectin complex and Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-surface protein, which belongs to the CXXC family of surface proteins, was reported by Cheng et al.55 Some CXXC motifs of the variant surface glycoproteins might implicate them in protein–protein interactions as they have signal peptide for cellular signaling. The decreased abundance of CXXC-rich protein in the vEh variant could be due to the low signal transduction among trophozoites and host receptor, particularly during the host–parasite interaction.

Hypothetical protein (EHI_138080) is one of the integral components of the membrane that is responsible for the cell transport. Based on the SMART sequence analysis, this protein contains short signal peptides between 1 and 22 amino acid residues and a TM region between 170 and 192 amino acid residues. This protein was also found in the uropod fraction of E. histolytica.39 According to the limited information, we postulate that the potential role of this protein in TM transport and signaling pathway is because of the presence of TM and signal peptide. However, further investigation is required to identify its actual role in E. histolytica.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that the application of iTRAQ-based quantitative approach could efficiently identify the differentially abundant membrane proteins between the vEh and avEh variants of E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS. Furthermore, this study has provided new knowledge on the putative roles of differentially abundant membrane proteins of the pathogenic E. histolytica HM-1:IMSS. Further investigations on the differentially abundant membrane proteins will be needed to elucidate the specific functional roles including those of hypothetical proteins to understand their roles in disease pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by Research University Grants (RUI), No. 1001/CIPPM/812118, from the Universiti Sains Malaysia. A. O.-G contribution is supported by grants CONACyT 247430 and DGAPA IN-214617 from Mexico. We thank Muhammad Hafiznur Yunus (Institute for Research in Molecular Medicine, Universiti Sains Malaysia) for his help with the technical assistance in the MALDI-TOF/TOF analysis, and Universiti Sains Malaysia Graduate Assistant Scheme for providing financial assistance to N. Y. L. during this study.

Note: Supplemental information and figure appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Samie A, ElBakri A, AbuOdeh RE, 2012. Amoebiasis in the tropics: epidemiology and pathogenesis. Rodriguez-Morales AJ, ed. Current Topics in Tropical Medicine. London, United Kingdom: IntechOpen, 201–226. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boettner DR, Huston C, Petri WA, 2002. Galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine lectin: the coordinator of host cell killing. J Biosci 27: 553–557. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mann BJ, 2002. Structure and function of the Entamoeba histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin. Int Rev Cytol 216: 59–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeMeester F, Shaw E, Scholze H, Stolarsky T, Mirelman D, 1990. Specific labeling of cysteine proteinases in pathogenic and non-pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica. Infect Immun 58: 1396–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mortimer L, Chadee K, 2010. The immunopathogenesis of Entamoeba histolytica . Exp Parasitol 126: 366–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laughlin RC, Temesvari LA, 2005. Cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie Entamoeba histolytica pathogenesis: prospects for intervention. Expert Rev Mol Med 7: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky SL, Matsudaira P, Baltimore D, Darnell J, 2000. Molecular Cell Biology, 4th edition Bethesda, Maryland: National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bookshelf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krogh A, Larsson B, Von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL, 2001. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes1. J Mol Biol 305: 567–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsirigos K, 2017. Bioinformatics methods for topology prediction of membrane proteins. Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Stockholm University. Available at: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1067468&dswid=-4009. Accessed May 11, 2018.

- 10.Nozaki T, Nakada-Tsukui K, 2006. Membrane trafficking as a virulence mechanism of the enteric protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica . Parasitol Res 98: 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stuart LM, Ezekowitz RAB, 2005. Phagocytosis: elegant complexity. Immunity 22: 539–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loftus B, Anderson I, Davies R, Alsmark UCM, 2005. The genome of the protist parasite Entamoeba histolytica . Nature 433: 865–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perdomo D, Aït-Ammar N, Syan S, Sachse M, Jhingan GD, Guillén N, 2015. Cellular and proteomics analysis of the endomembrane system from the unicellular Entamoeba histolytica . J Proteomics 112: 125–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biller L, et al. 2014. The cell surface proteome of Entamoeba histolytica . Mol Cell Proteomics 13: 132–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamond LS, Clark CG, Cunnick CC, 1995. YI-S, a casein-free medium for axenic cultivation of Entamoeba histolytica, related Entamoeba, Giardia intestinalis and Trichomonas vaginalis . J Eukaryot Microbiol 42: 277–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olivos A, Ramos E, Nequiz M, Barba C, Tello E, Castañón G, González A, Martínez RD, Montfort I, Pérez-Tamayo R, 2005. Entamoeba histolytica: mechanism of decrease of virulence of axenic cultures maintained for prolonged periods. Exp Parasitol 110: 309–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santos F, et al. 2015. Maintenance of intracellular hypoxia and adequate heat shock response are essential requirements for pathogenicity and virulence of Entamoeba histolytica . Cell Microbiol 17: 1037–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ujang JA, Kwan SH, Ismail MN, Lim BH, Noordin R, Othman N, 2016. Proteome analysis of excretory-secretory proteins of Entamoeba histolytica HM1: IMSS via LC–ESI–MS/MS and LC–MALDI–TOF/TOF. Clin Proteomics 13: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bodnar WM, Blackburn RK, Krise JM, Moseley MA, 2003. Exploiting the complementary nature of LC/MALDI/MS/MS and LC/ESI/MS/MS for increased proteome coverage. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 14: 971–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis PH, Zhang X, Guo J, Townsend RR, Stanley SL, 2006. Comparative proteomic analysis of two Entamoeba histolytica strains with different virulence phenotypes identifies peroxiredoxin as an important component of amoebic virulence. Mol Microbiol 61: 1523–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis PH, Chen M, Zhang X, Clark CG, Townsend RR, Stanley SL, Jr., 2009. Proteomic comparison of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar and the role of E. histolytica alcohol dehydrogenase 3 in virulence. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3: e415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams RB, Chan EK, Cowley MJ, Little PF, 2007. The influence of genetic variation on gene expression. Genome Res 17: 1707–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosch DE, Siderovski DP, 2013. G protein signaling in the parasite Entamoeba histolytica . Exp Mol Med 45: e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilchrist CA, et al. 2006. Impact of intestinal colonization and invasion on the Entamoeba histolytica transcriptome. Mol Biochem Parasitol 147: 163–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thibeaux R, Weber C, Hon CC, Dillies MA, Avé P, Coppée JY, Labruyère E, Guillén N, 2013. Identification of the virulence landscape essential for Entamoeba histolytica invasion of the human colon. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoek JB, Rydström J, 1988. Physiological roles of nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase. Biochem J 254: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okada M, Nozaki T, 2006. New insights into molecular mechanisms of phagocytosis in Entamoeba histolytica by proteomic analysis. Arch Med Res 37: 244–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Descoteaux S, Ayala P, Orozco E, Samuelson J, 1992. Primary sequences of two P-glycoprotein genes of Entamoeba histolytica . Mol Biochem Parasitol 54: 201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouellette M, Légaré D, Papadopoulou B, 2001. Multidrug resistance and ABC transporters in parasitic protozoa. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 3: 201–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orozco E, Lopez C, Gomez C, Perez DG, Marchat L, Banuelos C, Delgadillo DM, 2002. Multidrug resistance in the protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica . Parasitol Int 51: 353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bansal D, Sehgal R, Chawla Y, Malla N, Mahajan RC, 2006. Multidrug resistance in amoebiasis patients. Indian J Med Res 124: 189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alekshun MN, Levy SB, 2007. Molecular mechanisms of antibacterial multidrug resistance. Cell 128: 1037–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li XZ, Nikaido H, 2009. Efflux-mediated drug resistance in bacteria. Drugs 69: 1555–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nikaido H, 2009. Multidrug resistance in bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem 78: 119–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michalak M, Corbett EF, Mesaeli N, Nakamura K, Opas M, 1999. Calreticulin: one protein, one gene, many functions. Biochem J 344: 281–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.González E, et al. 2011. Entamoeba histolytica calreticulin: an endoplasmic reticulum protein expressed by trophozoites into experimentally induced amoebic liver abscesses. Parasitol Res 108: 439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.González E, Rico G, Mendoza G, Ramos F, García G, Morán P, Valadez A, Melendro EI, Ximénez C, 2002. Calreticulin-like molecule in trophozoites of Entamoeba histolytica HM1: IMSS (Swissprot: accession P83003). Am J Trop Med Hyg 67: 636–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ximénez C, et al. 2014. Entamoeba histolytica and E. dispar calreticulin: inhibition of classical complement pathway and differences in the level of expression in amoebic liver abscess. Biomed Res Int 2014: 127453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riekenberg S, Flockenhaus B, Vahrmann A, Müller MC, Leippe M, Kieß M, Scholze H, 2004. The beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase of Entamoeba histolytica is composed of two homologous chains and has been localized to cytoplasmic granules. Mol Biochem Parasitol 138: 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moncada D, Keller K, Chadee K, 2005. Entamoeba histolytica-secreted products degrade colonic mucin oligosaccharides. Infect Immun 73: 3790–3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riahi Y, Ankri S, 2000. Involvement of serine proteinases during encystation of Entamoeba invadens . Arch Med Res 31: S187–S189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Makioka A, Kumagai M, Kobayashi S, Takeuchi T, 2009. Involvement of serine proteases in the excystation and metacystic development of Entamoeba invadens . Parasitol Res 105: 977–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Markiewicz JM, Syan S, Hon CC, Weber C, Faust D, Guillen N, 2011. A proteomic and cellular analysis of uropods in the pathogen Entamoeba histolytica . PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5: e1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong H, Schotz MC, 2002. The lipase gene family. J lipid Res 43: 993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tillack M, Biller L, Irmer H, Freitas M, Gomes MA, Tannich E, Bruchhaus I, 2007. The Entamoeba histolytica genome: primary structure and expression of proteolytic enzymes. BMC genomics 8: 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Touz MC, Nores MJ, Slavin I, Piacenza L, Acosta D, Carmona C, Luján HD, 2002. Membrane-associated dipeptidyl peptidase IV is involved in encystation-specific gene expression during Giardia differentiation. Biochem J 364: 703–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gething MJ, Sambrook J, 1992. Protein folding in the cell. Nature 355: 33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tovy A, Hertz R, Siman-Tov R, Syan S, Faust D, Guillen N, Ankri S, 2011. Glucose starvation boosts Entamoeba histolytica virulence. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5: e1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta RS, Golding GB, 1993. Evolution of HSP70 gene and its implications regarding relationships between archaebacteria, eubacteria, and eukaryotes. J Mol Evol 37: 573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lo H, Reeves RE, 1978. Pyruvate-to-ethanol pathway in Entamoeba histolytica . Biochem J 171: 225–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harding JJW, Pyeritz EA, Copeland ES, White HB, 1975. Role of glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase in glyceride metabolism. Effect of diet on enzyme activities in chicken liver. Biochem J 146: 223–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Furukawa A, Nakada-Tsukui K, Nozaki T, 2013. Cysteine protease-binding protein family 6 mediates the trafficking of amylases to phagosomes in the enteric protozoan Entamoeba histolytica . Infect Immun 81: 1820–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barbosa-Cabrera E, Salas-Casas A, Rojas-Hernandez S, Jarillo-Luna A, Abarca-Rojano E, Rodríguez MA, Campos-Rodríguez R, 2012. Purification and cellular localization of the Entamoeba histolytica transcarboxylase. Parasitol Res 111: 1401–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raz E, Schejter ED, Shilo BZ, 1991. Interallelic complementation among DER/flb alleles: implications for the mechanism of signal transduction by receptor-tyrosine kinases. Genetics 129: 191–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng XJ, et al. 2001. Intermediate subunit of the Gal/GalNAc lectin of Entamoeba histolytica is a member of a gene family containing multiple CXXC sequence motifs. Infect Immun 69: 5892–5898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.