Abstract

Enterobacteriaceae, including Escherichia coli, has been shown to acquire the colistin resistance gene mcr-1. A strain of E. coli, EC11, which is resistant to colistin, polymyxin B and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, was isolated in 2016 from the feces of a dairy cow in Shanghai, China. Strain EC11 identifies with sequence type ST278 and is susceptible to 19 frequently used antibiotics. Whole genome sequencing of strain EC11 showed that this strain contains a 31-kb resistance plasmid, pEC11b, which belongs to the IncX4 group. The mcr-1 gene was shown to be inserted into a 2.6-kb mcr-1-pap2 cassette of pEC11b. Plasmid pEC11b also contained putative conjugal transfer components, including an oriT-like region, relaxase, type IV coupling protein, and type IV secretion system. We were successful in transferring pEC11b to E. coli C600 with an average transconjugation efficiency of 4.6 × 10-5. Additionally, a MLST-based analysis comparing EC11 and other reported mcr-positive E. coli populations showed high genotypic diversity. The discovery of the E. coli strain EC11 with resistance to colistin in Shanghai emphasizes the importance of vigilance in detecting new threats like mcr genes to public health. Detection of mcr genes helps in tracking, slowing, and responding to the emergence of antibiotic resistance in Chinese livestock farming.

Keywords: colistin resistance, mcr-1, Escherichia coli, IncX4 plasmid, whole genome sequence

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance is becoming a great challenge to public health worldwide (Laxminarayan et al., 2014). The rapid evolution of MDR Gram-negative bacteria is pushing humankind to the cusp of a post-antibiotic era. Colistin (polymyxins E) is a family of cationic polypeptide antibiotics which acts as the last line of defense in the treatment of severe bacterial infections by MDR or XDR bacteria. In particular, colistin is used to treat ESBL-producing and CRE infections (Li et al., 2006; Paterson and Harris, 2016).

Colistin resistance was assumed to be chromosomally mediated, non-transmissible and an intrinsic property of the bacteria (Olaitan et al., 2014). However, the recent discovery of the Escherichia coli harboring plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene mcr-1 confirms transmission of colistin resistance by HGT (Liu et al., 2016). The MCR-1 encodes a PEA transferase that adds PEA to the lipid A of the lipopolysaccharide, leading to Gram-negative bacteria resistant to colistin (Anandan et al., 2017). This HGT mechanism of colistin resistance has alarmed the medical, media, academic and public health communities.

The global spread of the mcr-1 gene is now evident and being documented. Currently, researchers have discovered five mcr-like genes, ranging from mcr-1 to mcr-5, with a series of mcr genetic variants such as mcr-1.2, mcr-1.3 …mcr-1.12. These mcr genes have spread to 40 countries across 5 of 7 continents in multiple ecosystems, including the environment, food, animals (e.g., pig, poultry, and cattle) and humans, and in over 11 species of Enterobacteriaceae (Schwarz and Johnson, 2016; Chen et al., 2017; Feng, 2018). Retrospective studies have shown that an isolate harboring the mcr-1 gene had already existed in three chicken E. coli isolates in China from the 1980s (Shen et al., 2016). The presence of mcr-1 in livestock is indicative of the route of mcr-1 dissemination through the food chain and it is gravely concerning that animal-to-human transmission of MCR-1 colistin resistance has already been found in many countries.

Mobile genetic elements such as conjugative plasmids, transposons, integrons and IS are important vehicles of HGT of the mcr-1 gene (Frost et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2018). Conjugative plasmids are the main driving force for the dissemination of the mcr-1 gene, and the plasmids IncI2 and IncX4 are the two leading plasmid types for facilitating the global dissemination of colistin resistance (Matamoros et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). The mcr-1 gene is part of an approximately 2.6-kb mcr-1-pap2 element that contains the likely promoter regions for mcr-1 transcription (Poirel et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). There are also rare cases involving chromosomally integrated mcr-1genes (Veldman et al., 2016; Tada et al., 2017), which are indicative of non-lineage-specific vertical dissemination of mcr-1.

Detection of mcr genes helps in the tracking, slowing, and responding to the emergence of antibiotic resistance in Chinese livestock farming. At the end of 2015, the mcr-1-harboring E. coli strain SHP45 was isolated from pigs in Shanghai (Liu et al., 2016). Also, in 2016, the colistin-resistant E. coli EC11 strain was isolated from cow feces collected from a commercial dairy farm. We will use WGS to outline the mechanism for acquiring and transferring colistin resistance in this strain.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Identification

In May 2016, we cultured E. coli strains from fecal samples collected from a commercial dairy farm in Shanghai, China. Samples (25 g) were dispensed in sterile plastic bags containing 225 ml of Mueller–Hinton broth and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. All samples were seeded on MacConkey agar plates with 2 μg/mL colistin and incubated at 37°C for 18 h. One putative positive E. coli colony per sample was selected on the basis of morphology, size, and color (peachblow), then inoculated overnight on eosin-methylene blue agar. Species were further confirmed by the amplification and sequencing of 16S rRNA, while SEM and TEM image analyses were conducted. All bacterial isolates were stored in the Luria-Bertani medium (Land Bridge, Beijing, China) with 30% glycerol at -80°C.

mcr-1 and β-Lactamase Gene Screening

Screening for the mcr-1 gene was performed using PCR amplification and sequencing. The specific primers used to produce the 309 bp amplicon were as previously described: CLR5-F (5′-CGGTCAGTCCGTTTGTTC-3′) and CLR5-R (5′-CTTGGTCGGTCTGTAGGG-3′) (Liu et al., 2016). Further screening for the presence of the mcr-2, mcr-3 and the main β-lactamase gene groups (blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, blaKPC, and blaNDM) was performed by previously reported primers. In this study, all primers used are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Each PCR reaction system was performed in 25 μL, containing 12.5 μL of PCR Mix (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), 9.5 μL of dd H2O, 1 μL of forward and reverse primers, and 1 μL of DNA template. Finally, one E. coli isolate designated as E. coli EC11 was determined to harbor the mcr-1 gene, and this isolate was selected to perform the follow-up experiments.

Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

The MIC for 22 common antibiotics was determined for the isolate of E. coli EC11 by the broth dilution method on Mueller–Hinton broth (Oxoid, United Kingdom) following incubation at 37°C for 18–24 h. In this study, the 22 tested antibiotics we used are categorized into seven groups as shown in Table 1. The results were interpreted according to CLSI document M100-S25 (2015)1 except for tigecycline and colistin, which were interpreted by the EUCAST (version 6.0)2 guidelines. The double disk test (ceftazidime + ceftazidime/clavulanic acid and cefotaxime + cefotaxime/clavulanic acid) was performed to confirm the ESBL phenotype, and E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as a quality control.

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (μg/mL) for Escherichia coli EC11, transconjugant EC11-T and recipient E. coli C600.

| Type of antibiotic | Antibiotic | MIC (μg/mL)∗ |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor | Transconjugant | Recipient | ||

| E. coli EC11 | E11-T | E. coli C600 | ||

| β-lactams | Amoxicillin-clavulanic | 2(S) | 2(S) | 2(S) |

| Ampicillin | 4(S) | 8(S) | 8(S) | |

| Piperacillin | 2(S) | 4(S) | 4(S) | |

| Cefotaxime | <0.125(S) | 0.25(S) | 0.25(S) | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.25(S) | 0.5(S) | 1(S) | |

| Cefoxitin | 8(S) | 4(S) | 4(S) | |

| Cephazolin | 2(S) | 4(S) | 4(S) | |

| Cefepime | <0.125(S) | 0.25(S) | <0.125(S) | |

| Imipenem | 0.5(S) | 1(S) | 0.5(S) | |

| Meropenem | <0.125(S) | <0.125(S) | <0.125(S) | |

| Aminoglycoside | Amikacin | 4(S) | 4(S) | 8(S) |

| Gentamicin | 2(S) | 1(S) | 1(S) | |

| Kanamycin | 4(S) | 4(S) | 4(S) | |

| Tetracycline | Tetracycline | 1(S) | 1(S) | 1(S) |

| Tigecycline | <0.125(S) | <0.125(S) | <0.125(S) | |

| Quinolone | Ciprofloxacin | <0.125(S) | 0.125(S) | <0.125(S) |

| Levofloxacin | <0.125(S) | 0.25(S) | 0.5(S) | |

| Nalidixic acid | 4(S) | >128(R) | >128(R) | |

| Amino alcohol | Chloramphenicol | 16(S) | 8(S) | 8(S) |

| Sulfonamide | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 8(R) | 8(R) | 8(R) |

| Cationic polypeptide | Polymyxin B | 4(R) | 4(R) | 1(S) |

| Colistin | 8(R) | 4(R) | 1(S) | |

MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; R, resistant; I, intermediate; S, susceptible.∗In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility was performed by broth microdilution method and the MICs were interpreted according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria, except for tigecycline, colistin and polymyxin B, which interpretation were performed according to the EUCAST guidelines.

Conjugation Assay

To determine whether the colistin resistance was carried on a transferable plasmid, a conjugation experiment by filter mating assay (Smith and Guild, 1980) was performed with rifampicin-resistant E. coli C600 as the recipient strain. Overnight cultures of the original isolates and recipient E. coli C600 in LB broth were adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard. A 10 μl aliquot of each culture was individually added to 2 ml of fresh LB broth and then incubated at 37°C for 6 h. The original strains (20 μl) were then separately conjugated with E. coli C600 (60 μl) on a microporous membrane. Transconjugants were selected on MacConkey agar plates supplemented with colistin (2 μg/mL) and rifampicin (40 μg/mL), and putative transconjugants were confirmed by both PCR and an antimicrobial susceptibility test (above 22 antibiotics). The mobilization efficiency was calculated as the number of transconjugant colonies divided by the number of donor colonies (Wang et al., 2011).

Multilocus Sequence Typing

The clonal lineage of the E. coli EC11 strain was studied using MLST. MLST was performed as previously described (Tartof et al., 2005). The seven conserved housekeeping genes (adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, and recA) were chosen as targets3 and PCR fragments were sequenced. The alignments of these sequences were determined using DNAMAN software. These sequences were then analyzed using the facility provided by the above-mentioned online tool to assign allele numbers and define the ST and CC.

Furthermore, in order to explore possible genetic relationships between E. coli EC11 and other E. coli isolates harboring mcr reported worldwide, we performed a systematic review of the literature on mcr published in the NCBI-Pubmed database between November 2015 and March 2018. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using a NJ method by MEGA5.0 software, where the phylogenetic relationships among different strains were analyzed based on nucleotide differences. In addition, we conducted cluster analysis of these strains to understand the relationship between the different ST groups. The eBURST algorithm was used to group strains according to their allelic profiles by employing a user-specified group definition as well as drawing a rough sketch4 to show the genetic relationship.

Whole Genome Sequencing

Genomic DNA of E. coli strain EC11 was extracted from an overnight culture using the TIANamp Bacteria DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech Beijing Co., Ltd., China) according to manufacturer’s instructions. WGS data were generated using short-read (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States), producing 2 × 251-bp paired-end reads, and long-read (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, United States) technology. The raw data were assembled using SPAdesv3.9.0 (Bankevich et al., 2012). Gene prediction and annotation were done with Glimmer 3.02 and BLAST. All sequences were deposited under the Bioproject PRJNA436212. Serotypes, plasmid replicons, and E. coli virulence genes were identified by using SerotypeFinder1.1, PlasmidFinder1.3, and VirulenceFinder1.5, respectively, available from the Center for Genomic Epidemiology5. Insertion sequence (IS) elements were identified using ISfinder6. Additional characterization of chromosomal resistance determinants was performed using the CARD Resistance Gene Identifier7, and ResFinder8 was used to detect acquired resistance genes commonly located on mobile genetic elements. The sequence comparison and map generation were performed using BLAST9 and Easyfig version 2.1 (Sullivan et al., 2011). Conjugal transfer components of the plasmids were performed using oriTfinder (Li et al., 2018).

Results

Identification of mcr-1-Positive E. coli Isolates

In our study, out of 120 E. coli isolates collected from dairy cow fecal samples in May 2016 in Shanghai, only the E. coli isolate EC11 (Supplementary Figures S1, S2) carried the mcr-1gene, and none of these isolates carried mcr-2/3 determinants or the allelic variants.

Susceptibility to Antimicrobial and Conjugative Compounds

According to EUCAST standards, the resistance cutoff of E. coli to colistin is 2 mg/L and the E. coli EC11 strain exhibited the lower level of colistin resistance (8 μg/mL) (Table 1). E. coli EC11 also showed resistance to polymyxin B, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; but it was susceptible to other 19 common antibiotics, including amoxicillin-clavulanic, ampicillin, piperacillin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefoxitin, cephazolin, cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, amikacin, gentamicin, kanamycin, tetracycline, tigecycline, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, nalidixic acid, chloramphenicol (Table 1). PCR results showed that E. coli EC11 didn’t carry the β-lactamase genes, including blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, blaKPC, and blaNDM. Furthermore, the double disk test suggested that E. coli EC11 was a non-ESBL producing isolate (Supplementary Figure S3).

In addition, the filter mating assays indicated that the mcr-1-carrying plasmid could be successfully transferred from the donor (E. coli EC11) to the recipient (E. coli C600) with an average efficiency of 4.6 × 10-5. The MIC value of the transconjugant EC11-T to colistin was 8 μg/mL, which showed an eightfold increase when compared with the recipient E. coli C600 (1 μg/mL). The transconjugant E. coli EC11-T was also found to have resistance to nalidixic acid, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and polymyxin B.

A Diversity of the mcr-1 Positive E. coli Isolates

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) showed that E. coli EC11 belonged to the ST278 lineage. Based on the literature review, details of the E. coli strains harboring mcr genes, including the source and year of isolation, the presence of the MDR phenotype, ST, and allelic profile, are presented in Supplementary Table S2. A total of 245 STs were identified among the 616 E. coli isolates, indicating a high degree of genotypic diversity.

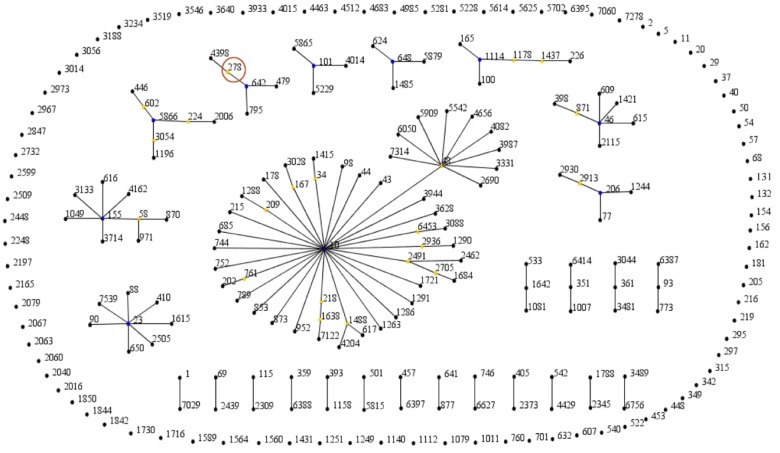

The application of eBURST resolved the 245 STs into 10 clonal complexes (CC10, CC206, CC46, CC1114, CC648, CC101, CC642, CC6866, CC55, and CC23). CC10 remained the most populated clonal complex and ST10 was defined as the ancestral type of CC10 (Figure 1). The geographical distribution of the different STs is shown in Supplementary Table S3. These ST types were distributed in more than 35 cities across six continents. ST10 was isolated on five continents and China was the country where the most mcr-positive E. coli strains were found, with as many as 162 different STs being discovered.

FIGURE 1.

The eBURST cluster analysis of the genetic relationships of the mcr-positive Escherichia coli strains. The analysis is based on allelic profiles of MLST data and displays clusters of linked and individual unrelated STs. The digital represents the ST type, each black node represents a sequence type, the blue nodes represent clonal ancestors, the yellow nodes represent clonal subpopulation ancestors, and the red circle represents the sequence type of E. coli EC11 in this study.

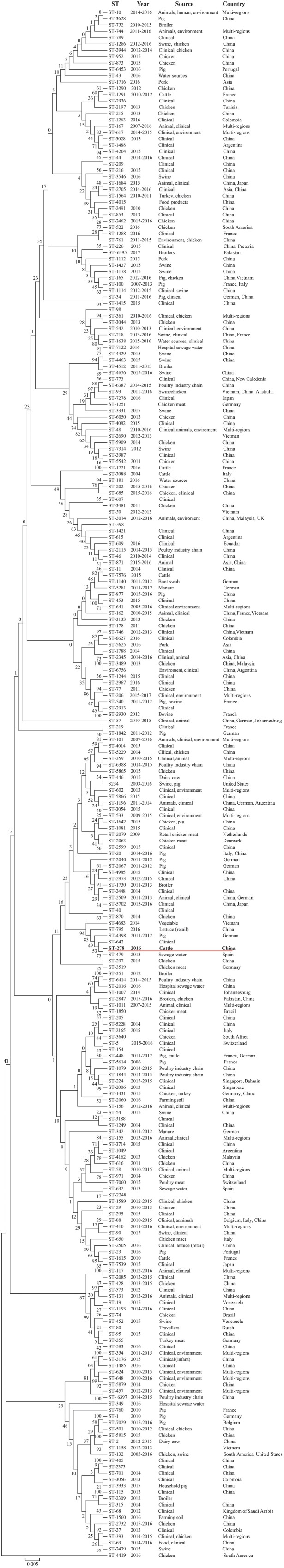

A NJ tree representing the concatenated sequences of the seven housekeeping gene fragments in 245 mcr-positive E. coli isolates of different ST types is shown in Figure 2. The phylogenetic analyses revealed that E. coli isolates harboring mcr genes were distributed in different lineages, and the isolated E. coli EC11 was located on a single branch rather than belonging to one of the ST10 branches.

FIGURE 2.

Neighbor-joining tree of 245 concatenated sequences of E. coli harboring mcr-1 from multiple sources in different countries. The numbers at the nodes represent bootstrap values based on 500 replications. In bold and red underline presented the E. coli EC11isolate. ST, sequence type.

Genome Features of E. coli EC11 Harboring mcr-1

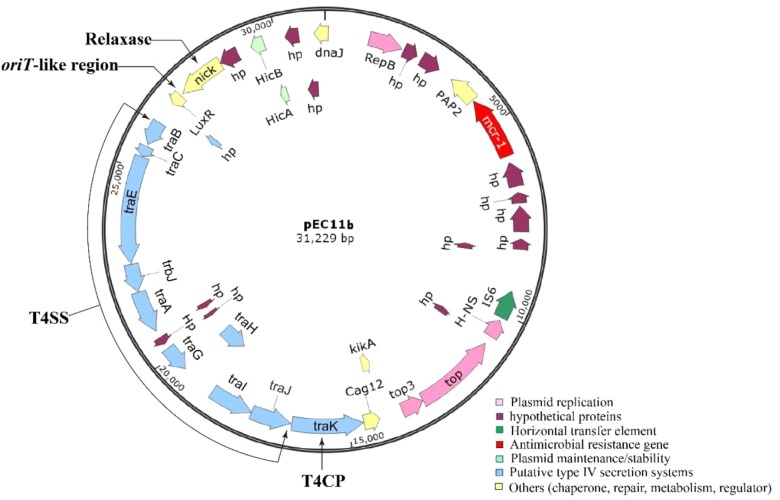

Whole gene sequencing (WGS) revealed that the serotype of the E. coli EC11 strain was H7. E. coli EC11 consisted of a chromosome and four circular plasmids (pEC11a, pEC11b, pEC11c, and pEC11d) (Table 2). The chromosome genome size presented 4,933,784 bp, with a G+C content of 47.6%. With an exception of the mcr-1, unexpectedly, any other resistance genes were not defective in EC11. WGS results revealed the mcr-1 gene, which showed 100% BLASTn identities to the known mcr-1 gene of the reference plasmid pHNSHP45 of E. coli SHP45 (Liu et al., 2016). The mcr-1 gene was only located on plasmid pEC11b, which was 31,229 bp in length and had an average G+C content of 41.40%, encoding 38 ORFs (Figure 3). Using PlasmidFinder, the plasmid pEC11b had a typical IncX4 plasmid backbone encoding replication, conjugation apparatus and stability functions, and was probably responsible for the movement of the plasmid between different bacterial hosts. The type II toxin–antitoxin module hicA/hicB was also identified in pEC11b. The putative virulence genes, such as gad (coding for glutamate decarboxylase), lpfA (long polar fimbriae) and iss (increased serum survival siderophore), were found in the chromosome of E. coli EC11.

Table 2.

General features of E. coli EC11 genomes.

| Replicons | Accession number | Size(bp) | MLST | Plasmid typing | Antibiotic resistance | GC (%) | ORF numbers | tRNA genes | rRNA genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | CP027255 | 4,933,784 | ST278 | – | – | 50.77 | 4,648 | 85 | 22 |

| pEC11a | CP027256 | 103,336 | – | IncFIB | – | 48.08 | 119 | 0 | 0 |

| pEC11b | CP027257 | 31,229 | – | IncX4 | mcr-1 | 41.74 | 38 | 0 | 0 |

| pEC11c | CP027258 | 31,467 | – | – | – | 48.41 | 46 | 0 | 0 |

| pEC11d | CP027259 | 6,812 | – | ColRNAI | – | 47.69 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

FIGURE 3.

Map of the mcr-1-containing plasmid pEC11b isolated. The mcr-1 gene is marked in red. Figure was created with by the software SnapGene Viewer.

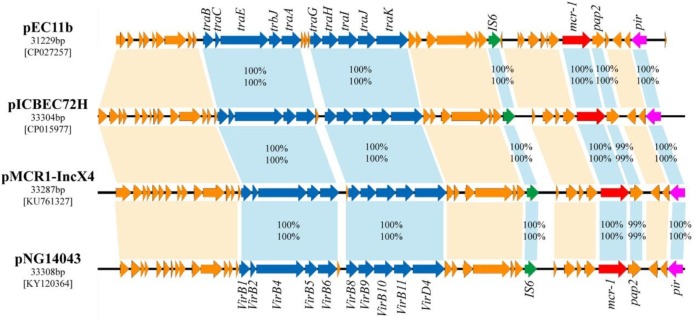

Genome Features of mcr-1-Carried Plasmid

BLASTn analysis showed that the backbone of the plasmid pEC11b (GenBank accession number CP027257.1) was strikingly similar with (the query cover of 100% and the identities 99%) other previously sequenced mcr-1-carrying IncX4 plasmids, such as pICBEC72H of E. coli (isolated in Brazil; the GenBank accession no. CP015977.1), pMCR1-IncX4 of Klebsiella pneumoniae (China; KU761327.1), and pNG14043 of Salmonella (China; KY120364) (Figure 4). In all, these IncX4 plasmids bearing mcr-1 showed very high architectural conservation.

FIGURE 4.

Linear comparison of complete plasmid sequences of plasmid pEC11b from E. coli EC11 (this study, accession no. CP027257), pICBEC72H from E. coli ICBEC72H (CP015977), pMCR1-IncX4 from Klebsiella pneumoniae SZ04 (KU761327) and pNG14043 from Salmonella NG14043 (KY120364). The arrows represent the position and transcriptional direction of the ORFs. Genes associated with the type IV secretion systems are indicated by blue arrows, resistance genes are indicated by red arrows, replication initiation protein are indicated pink, while accessory genes are indicated by jacinth arrows. Insertion sequences are highlighted in green arrows. The percentages of amino acid identity (above) and nucleic acid similarity (below) are shown between the homologous genes.

An approximately 2.6 kb mcr-1-pap2 element was identified in the above-mentioned plasmids pEC11b, PICBEC72H, pMCR1-IncX4, and PNG14043. In addition, an IS6 element was identified in pEC11b, IS26 was identified in PICBEC72H and PNG14043, and tnpA was identified in pMCR1-IncX4 (Figure 4). The promoter sequences of mcr-1 in all the aforementioned sequences were similar to that of pAf23 and pAf48 reported by Poirel et al (Poirel et al., 2016) as well as pMCR1_IncI2 and BJ10 by Zhang et al (Zhang et al., 2017) (Supplementary Figure S4).

The putative conjugal transfer components of pEC11b were also detected by using oriTfinder. A tra gene cluster encoding a T4SS belonging to Type P was predicted on pEC11b. It encoded a relaxase (C6C13_26300) belonging to the MOBP family. It also encoded a T4CP (C6C13_26225) belonging to the VirD4 subfamily. The oriT-like region (coordinate: 27,146-27,223 bp) contained a pair of 14-bp IRs (GCAGGTGAGCAAAG…CTTTGTTCACCTGC). This evidence confirms that the plasmid pEC11b is a conjugative plasmid.

Discussion

Colistin has been widely used as a veterinary drug for the treatment of enterobacterial infections and as an in-feed additive to promote healthy development in food-producing animals, especially in swine and poultry production (Kempf et al., 2013, 2016). Transfer of colistin resistance among bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract of livestock animals is a probable route for the dissemination of these bacteria (Fernandes et al., 2016b; Guenther et al., 2017). These routes can be via the food chain or direct human contact with animals as well as through contamination of fresh and seawater systems (Zhang et al., 2016; Zurfuh et al., 2016). In addition, the persistence of mcr-1 in the human gastrointestinal tract microflora provides another route for dissemination of these bacteria (Chen et al., 2017). In this study, the mcr-1-carrying plasmid could be conjugated into E. coli C600 isolates in vitro. The mcr-1 gene, if present in gut microbiota, can therefore be horizontally transmitted between different species in the microbiota.

Self-transmissible IncX4-type plasmids are now accepted as key vehicles responsible for the dissemination of the mcr-1 gene among Enterobacteriaceae worldwide (Fernandes et al., 2016a; Sun J. et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017). In this study, we identified an IncX4-type plasmid carrying mcr-1 in E. coli EC11, pEC11b, which was nearly identical to the other IncX4 plasmids bearing mcr-1 in GenBank. IncX4 plasmid architecture is highly conserved and studies have shown similar IncX4 plasmids bearing mcr-1 from different species. These species were isolated from different geographic locations and belonged to different STs (Sun J. et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017). Plasmid pEC11b has four typical conjugal modules: an origin of transfer (oriT-like) region, a T4CP gene, a relaxase gene, and a gene cluster for the bacterial T4SS apparatus. The T4SS can act as a conjugative machine in conjugative plasmids (Cascales and Christie, 2003). These gene clusters are vital to the HGT of intra- and inter-species bacterial resistance genes (Frost et al., 2005). Also, the plasmid pEC11b contains the mcr-1-pap2 cassette which has proven that it could be horizontally transferred into diverse plasmid replicon types (Li et al., 2016).

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) is a powerful genetic fingerprinting technique for molecular epidemiology and population genetic studies of bacterial pathogens (Maiden et al., 1998; Urwin and Maiden, 2003; Maiden, 2006). In this study, we reported the first recorded instance of an mcr-1 producing E. coli EC11 belonging to the ST278 lineage. We performed a MLST-based analysis of the mcr-positive E. coli population structure among 616 isolates collected in different laboratories in over 35 countries since 2016. The 245 STs among the 616 isolates indicate that the mcr-positive E. coli population is extremely diverse. Applying eBURST and NJ tree analyses simultaneously in this global dataset allows for better resolution in discerning the epidemiology and genetic population structure of mcr-positive isolates. Combined with previous studies (Matamoros et al., 2017), we speculate that the diversity in ST types of these E. coli strains may be related to highly promiscuous plasmids disseminating mcr genes. It also indicates that mcr-1 has a huge risk of vertical transmission and may become more widespread and prevalent in the future. A ST which is highly disseminated in food, environment, animals, and human intestinal samples is ST10 (Matamoros et al., 2017; Sun P. et al., 2017). The epidemic clone ST131 (Ortiz de la Tabla et al., 2017), ST648 (Yang et al., 2016), and ST206 (Zheng et al., 2018) were reported to be the most common STs associated with various β-lactamases, including ESBLs, NDM, and KPCs, etc. Many reports indicated that bacteria carrying mcr-1 were often associated with ESBLs (Sun et al., 2016). In this study, E. coli EC11 only conferred resistance to polymyxin B, colistin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, which are antibiotics that are extensively prescribed in veterinary medicine (Catry et al., 2015).

Currently, a number of countries have already restricted the use of colistin in animal production. China has now stopped the use of colistin as an antibiotic growth promoter (Walsh and Wu, 2016). South Africa has responded to the threat of losing colistin as an antibiotic for human health through a program to advance national stewardship of colistin across the ‘One Health’ platform (Mendelson et al., 2018). The discovery of the E. coli strain EC11 with resistance to colistin in Shanghai emphasizes the importance of vigilance in detecting new threats like mcr genes to public health.

Conclusion

In this work, we report the first case of colistin-resistant mcr-1 gene in E. coli strain EC11 isolated from dairy cow feces in Shanghai, China. We show that this E. coli strain carrying the mcr-1 gene can transfer resistance through HGT. This study confirms the need to monitor and survey the use of colistin and other types of antibiotics to enable proactive and effective strategies (e.g., risk assessment and risk management) for preserving the efficacy of antibiotics in the future.

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Number

The genome sequences of the chromosome and four plasmids of the E. coli strain EC11 were deposited as GenBank accession no. CP027255-CP027259.

Author Contributions

YZ, YP, and HL conceived and supervised the study. FB designed the experiments. FB and ZZ performed the experiments. FB and XL analyzed the data. BN and XL revised the paper. PM edited the paper. FB wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Life Sciences & Biology Laboratory for presenting the E. coli C600 strain.

Abbreviations

- CC

clonal complexes

- CLSI

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- CRE

carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae

- E. coli

Escherichia coli

- ESBL

extended spectrum β-lactamase

- EUCAST

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- HGT

horizontal gene transfer

- IRs

inverted repeats

- IS

insertion sequences

- MDR

multidrug-resistant

- MIC

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

- MLST

Multilocus Sequence Typing

- NJ

Neighbor-joining

- ORFs

open reading frames

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PEA

phosphoethanolamine

- SEM

scanning electron microscope

- ST

sequence type

- T4CP

type IV coupling protein

- T4SS

type IV secretion system

- TEM

transmission electron microscope

- WGS

whole-genome sequencing

- XDR

extensively drug-resistant

Funding. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31571917 and 31671779), Shanghai Agriculture Applied Technology Development Program (Grant Nos. G20160101 and T20170404), Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2017-01-07-00-10-E00056), and the “Dawn” Program of Shanghai Education Commission (15SG48).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02833/full#supplementary-material

References

- Anandan A., Evans G., Condic-Jurkic K., O’Mara M., John C., Phillips N., et al. (2017). Structure of a lipid a phosphoethanolamine transferase suggests how conformational changes govern substrate binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 2218–2223. 10.1073/pnas.1612927114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A. A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A. S., et al. (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19 455–477. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascales E., Christie P. (2003). The versatile bacterial type IV secretion systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1 137–149. 10.1038/nrmicro753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catry B., Cavaleri M., Baptiste K., Grave K., Grein K., Holm A., et al. (2015). Use of colistin-containing products within the European Union and European Economic Area (EU/EEA): development of resistance in animals and possible impact on human and animal health. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 46 297–306. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Chan E., Xie M., Ye L., Dong N., Chen S. (2017). Widespread distribution of bearing bacteria in the ecosystem, 2015 to 2016. Euro. Surveill 22 17–00206. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.39.17-00206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. (2018). Transferability of MCR-1/2 polymyxin resistance: complex dissemination and genetic mechanism. ACS Infect. Dis. 4 291–300. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes M. R., McCulloch J. A., Vianello M. A., Moura Q., Perez-Chaparro P. J., Esposito F., et al. (2016a). First report of the globally disseminated incx4 plasmid carrying the mcr-1 gene in a colistin-resistant Escherichia coli sequence type 101 isolate from a human infection in Brazil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 6415–6417. 10.1128/AAC.01325-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes M. R., Moura Q., Sartori L., Silva K. C., Cunha M. P., Esposito F., et al. (2016b). Silent dissemination of colistin-resistant Escherichia coli in South America could contribute to the global spread of the mcr-1 gene. Euro. Surveill 21 2–7. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.17.30214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost L., Leplae R., Summers A., Toussaint A. (2005). Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3 722–732. 10.1038/nrmicro1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther S., Falgenhauer L., Semmler T., Imirzalioglu C., Chakraborty T., Roesler U., et al. (2017). Environmental emission of multiresistant Escherichia coli carrying the colistin resistance gene mcr-1 from German swine farms. J Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 1289–1292. 10.1093/jac/dkw585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempf I., Fleury M., Drider D., Bruneau M., Sanders P., Chauvin C., et al. (2013). What do we know about resistance to colistin in Enterobacteriaceae in avian and pig production in Europe? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 42 379–383. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempf I., Jouy E., Chauvin C. (2016). Colistin use and colistin resistance in bacteria from animals. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 48 598–606. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxminarayan R., Duse A., Wattal A. (2014). Antibiotic resistance-the need for global solutions (vol 13,pg 1057, 2013). Lancet Infect. Dis. 14 675–675. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A., Yang Y., Miao M., Chavda K. D., Mediavilla J. R., Xie X., et al. (2016). Complete sequences of mcr-1-harboring plasmids from extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 4351–4354. 10.1128/AAC.00550-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Nation R., Turnidge J., Milne R., Coulthard K., Rayner C., et al. (2006). Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6 589–601. 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70580-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Xie Y., Liu M., Tai C., Sun J., Deng Z., et al. (2018). oriTfinder: a web-based tool for the identification of origin of transfers in DNA sequences of bacterial mobile genetic elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 W229–W234. 10.1093/nar/gky352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. Y., Wang Y., Walsh T. R., Yi L. X., Zhang R., Spencer J., et al. (2016). Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16 161–168. 10.1016/s1473-3099(15)00424-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiden M. (2006). Multilocus sequence typing of bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60 561–588. 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiden M., Bygraves J., Feil E., Morelli G., Russell J., Urwin R., et al. (1998). Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 95 3140–3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matamoros S., van Hattem J. M., Arcilla M. S., Willemse N., Melles D. C., Penders J., et al. (2017). Global phylogenetic analysis of Escherichia coli and plasmids carrying the mcr-1 gene indicates bacterial diversity but plasmid restriction. Sci. Rep. 7:15364. 10.1038/s41598-017-15539-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson M., Brink A., Gouws J., Mbelle N., Naidoo V., Pople T., et al. (2018). The One Health stewardship of colistin as an antibiotic of last resort for human health in South Africa. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18 e288–e294. 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30119-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olaitan A., Morand S., Rolain J. (2014). Mechanisms of polymyxin resistance: acquired and intrinsic resistance in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 5:643 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz de la Tabla V., Ortega A., Bunuel F., Perez-Vazquez M., Marcos B., Oteo J. (2017). Detection of the high-risk clone ST131 of Escherichia coli carrying the colistin resistance gene mcr-1 and causing acute peritonitis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 49 115–116. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson D. L., Harris P. N. (2016). Colistin resistance: a major breach in our last line of defence. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16 132–133. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00463-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L., Kieffer N., Brink A., Coetze J., Jayol A., Nordmann P. (2016). Genetic features of MCR-1-producing colistin-resistant Escherichia coli isolates in South Africa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 4394–4397. 10.1128/AAC.00444-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz S., Johnson A. P. (2016). Transferable resistance to colistin: a new but old threat. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 2066–2070. 10.1093/jac/dkw274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z., Wang Y., Shen Y., Shen J., Wu C. (2016). Early emergence of mcr-1 in Escherichia coli from food-producing animals. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16 293–293. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00061-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M., Guild W. (1980). Improved method for conjugative transfer by filter mating of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 144 457–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M., Petty N., Beatson S. (2011). Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 27 1009–1010. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Fang L. X., Wu Z., Deng H., Yang R. S., Li X. P., et al. (2017). Genetic analysis of the IncX4 plasmids: implications for a unique pattern in the mcr-1 acquisition. Sci. Rep. 7:424. 10.1038/s41598-017-00095-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P., Bi Z., Nilsson M., Zheng B., Berglund B., Stalsby Lundborg C., et al. (2017). Occurrence of blaKPC-2, blaCTX-M, and mcr-1 in Enterobacteriaceae from well water in rural China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:e02569-16. 10.1128/AAC.02569-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Li X. P., Yang R. S., Fang L. X., Huo W., Li S. M., et al. (2016). Complete nucleotide sequence of an IncI2 plasmid coharboring blaCTX-M-55 and mcr-1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 5014–5017. 10.1128/AAC.00774-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Zhang H., Liu Y., Feng Y. (2018). Towards understanding MCR-like colistin resistance. Trends Microbiol. 26 794–808. 10.1016/j.tim.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada T., Nhung P. H., Shimada K., Tsuchiya M., Phuong D. M., Anh N. Q., et al. (2017). Emergence of colistin-resistant Escherichia coli clinical isolates harboring mcr-1 in Vietnam. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 63 72–73. 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartof S. Y., Solberg O. D., Manges A. R., Riley L. W. (2005). Analysis of a uropathogenic Escherichia coli clonal group by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43 5860–5864. 10.1128/jcm.43.12.5860-5864.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urwin R., Maiden M. (2003). Multi-locus sequence typing: a tool for global epidemiology. Trends Microbiol. 11 479–487. 10.1016/j.tim.2003.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldman K., van Essen-Zandbergen A., Rapallini M., Wit B., Heymans R., van Pelt W., et al. (2016). Location of colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in Enterobacteriaceae from livestock and meat. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 2340–2342. 10.1093/jac/dkw181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh T. R., Wu Y. (2016). China bans colistin as a feed additive for animals. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16 1102–1103. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30329-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Xiong Y., Lan R., Ye C., Wang H., Ren J., et al. (2011). pO157_Sal, a novel conjugative plasmid detected in outbreak isolates of Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49 1594–1597. 10.1128/JCM.02530-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Sun J., Li J., Ding Y., Li X. P., Lin J., et al. (2017). Expanding landscapes of the diversified mcr-1-bearing plasmid reservoirs. Microbiome 5:70. 10.1186/s40168-017-0288-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., van Dorp L., Shaw L., Bradley P., Wang Q., Wang X., et al. (2018). The global distribution and spread of the mobilized colistin resistance gene mcr-1. Nat. Commun. 9:1179. 10.1038/s41467-018-03205-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R. S., Feng Y., Lv X. Y., Duan J. H., Chen J., Fang L. X., et al. (2016). Emergence of NDM-5- and MCR-1-producing Escherichia coli clones ST648 and ST156 from a single muscovy duck (Cairina moschata). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 6899–6902. 10.1128/AAC.01365-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Miao M., Yan J., Wang M., Tang Y., Kreiswirth B., et al. (2017). Expression characteristics of the plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene. Oncotarget 8 107596–107602. 10.18632/oncotarget.22538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. F., Doi Y., Huang X., Li H. Y., Zhong L. L., Zeng K. J., et al. (2016). Possible transmission of mcr-1-harboring Escherichia coli between companion animals and human. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 22 1679–1681. 10.3201/eid2209.160464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B., Lv T., Xu H., Yu X., Chen Y., Li J., et al. (2018). Discovery and characterisation of an Escherichia coli ST206 strain producing NDM-5 and MCR-1 from a patient with acute diarrhoea in China. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 51 273–275. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurfuh K., Poirel L., Nordmann P., Nuesch-Inderbinen M., Hachler H., Stephan R. (2016). Occurrence of the plasmid-borne mcr-1 colistin resistance gene in extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in river water and imported vegetable samples in Switzerland. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 2594–2595. 10.1128/aac.00066-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.