SUMMARY

The +1 nucleosome of yeast genes, within which reside transcription start sites, is characterized by histone acetylation, by the displacement of an H2A-H2B dimer, and by a persistent association with the RSC chromatin-remodeling complex. Here we demonstrate the interrelationship of these characteristics and the conversion of a nucleosome to the +1 state in vitro. Contrary to expectation, acetylation performs an inhibitory role, preventing the removal of a nucleosome by RSC. Inhibition is due to both enhanced RSC-histone interaction and diminished histone-chaperone interaction. Acetylation does not prevent all RSC activity, as stably bound RSC removes an H2A-H2B dimer on a time scale of seconds in an irreversible manner.

In Brief

The RSC chromatin remodeling complex is persistently associated with the +1 nucleosome of yeast genes in vivo though the nucleosome is not removed. Lorch et al. address this paradox by showing that histone acetylation by the SAGA complex inhibits RSC activity in vitro.

Graphical Abstract:

INTRODUCTION

The wrapping of promoter DNA around a histone octamer in the nucleosome represses the initiation of transcription by purified RNA polymerase and general transcription factors (Lorch et al., 1987). Histones cause similar repression in vivo, as shown by the depletion of nucleosomes and consequent up-regulation of transcription (Han and Grunstein, 1988). Repression by histones is believed to play a general role in transcriptional regulation: it maintains a near zero level of expression of all genes except those whose transcription is brought about by specific, positive regulatory mechanisms.

Chromatin remodeling relieves repression by the nucleosome. The machinery for remodeling includes multiprotein complexes, whose founding member, the SWI/SNF complex, was discovered by genetic studies in yeast (Stern et al., 1984). The most abundant remodeling complex, termed RSC, is essential for cell growth (Cairns et al., 1996). The catalytic component of remodeling complexes is an ATP-dependent translocase, which slides DNA through the nucleosome (Saha et al., 2002; Zofall et al., 2006), and which may dislodge the DNA completely, transferring the histones to a chaperone protein (Lorch et al., 2006) or to another DNA molecule (Lorch et al., 1999).

Genetic studies and genome-wide analyses in yeast have shown distinctive sets of targets of SWI/SNF complex, RSC, and other chromatin remodeling complexes. RSC is found associated preferentially with promoters and intergenic regions, rather than open reading frames (Ng et al., 2002). It is generally located at RNA polymerase III promoters, and is specifically recruited to RNA polymerase II promoters under conditions of transcriptional activation or, in some circumstances, transcriptional repression. Many classes of genes exhibit RSC-dependence, including those involved in biosynthesis, metabolism, cell structure, chromosome structure, and transcription control.

RSC remodels promoter chromatin (Hartley and Madhani, 2009; Lorch et al., 2011), creating a nucleosome-free region, flanked by strongly positioned nuclesomes (Yuan et al., 2005). Genome-wide studies have implicated additional remodeling complexes and protein factors in the process (Krietenstein et al., 2016). Regulatory DNA sequences and TATA-like sequences lie within the nucleosome-free region, whereas transcription start sites (TSSs) often lie within a flanking (+1) nucleosome.

Two recent studies have demonstrated a perturbation of structure of the +1 nucleosome, and have implicated RSC in the process. Incorporation of a copper-phenantholine moiety in histone H4 and cleavage of the associated DNA with hydrogen peroxide revealed a pronounced asymmetry of +1 nucleosomes of yeast genes (Ramachandran et al., 2015): cleavage was more frequent on one side of the dyad axis of the nucleosome than on the other. By contrast, the vast majority of yeast nucleosomes showed only symmetric cleavage. A similar asymmetry was noted in the pattern of micrococcal nuclease digestion of +1 nucleosomes. These findings were attributed to partial unwrapping of DNA from the +1 nucleosome. It was further shown that RSC is associated with asymmetric +1 nucleosomes and is instrumental in transcription of genes with such asymmetric nucleosomes.

A second study employed ChIP-exo for mapping contacts of histones with nucleosomal DNA (Rhee et al., 2014). An asymmetry in abundance of contacts was observed for the +1 nucleosome. In both cleavage and ChIP-exo studies, the direction of the asymmetry was uncorrelated with the direction of transcription, with partial unwrapping of about half the nucleosomes on the upstream side and half on the downstream side. Chromatin immunoprecipitation has also given evidence for interaction of the pol II transcription machinery with the +1 nucleosome (Rhee and Pugh, 2012).

Partial unwrapping of DNA was previously revealed by cryo-EM structures of RSC and of a RSC-nucleosome complex at about 25 Å resolution (Chaban et al., 2008). A difference electron density map showed RSC largely surrounding the nucleosome. The structure of RSC was not much affected by nucleosome-binding, but the structure of the nucleosome was altered. Much of the DNA was displaced from the surface of the histone octamer and was presumably in contact with RSC. One of the two H2A-H2B dimers was apparently displaced from its normal position as well.

The conclusions drawn from cryo-EM were supported by results of DNase digestion (Lorch et al., 2010), showing that RSC binding exposed nucleosomal DNA to cleavage by DNase I. These findings were attributed to release of DNA from the surface of the nucleosome and interaction with RSC; DNA is transferred from binding sites on the histone octamer to a positively charged surface of RSC. Evidence for a positively charged, DNA-binding surface of RSC has come from measurement of RSC-DNA interaction: RSC binds to DNA with about the same affinity as it does to a nucleosome (Lorch et al., 1998).

The interaction of RSC with the +1 nucleosome of transcriptionally active promoters may explain the partial unwrapping of DNA, but it is also paradoxical. RSC slides and evicts nucleosomes in the presence of ATP in vitro, in apparent contradiction with the strong positioning and persistence of the +1 nucleosome in vivo. We report here on the resolution of this paradox, due to histone modification and consequent effects on RSC activities.

RESULTS

Inhibition of RSC activity by histone acetylation

The most prominent post-translational modification of histones in transcribed regions is acetylation of lysine residues, especially in the amino-terminal tails of H3 and H4. Acetylation is especially abundant in the vicinity of the promoter (Kuo et al., 1998; Reinke and Horz, 2003), including the histones of the +1 nucleosome. Histone acetylation is catalyzed by a number of enzymes, including the Gcn5 subunit of the SAGA complex, which targets H3 residues K9 and K14, and the Esa1 subunit of the NuA4 complex, which preferentially acetylates H4K12, but which can acetylate other residues in H4, and in H2A, and H3 as well (Kuo et al., 2015). SAGA is required for the initiation of transcription (Baptista et al., 2017), and so is likely responsible for acetylation of the +1 nucleosome. NuA4 is implicated in DNA damage repair and cell cycle progression (Smith et al., 1998; Allard et al., 1999; Clarke et al., 1999; Boudreault et al., 2003).

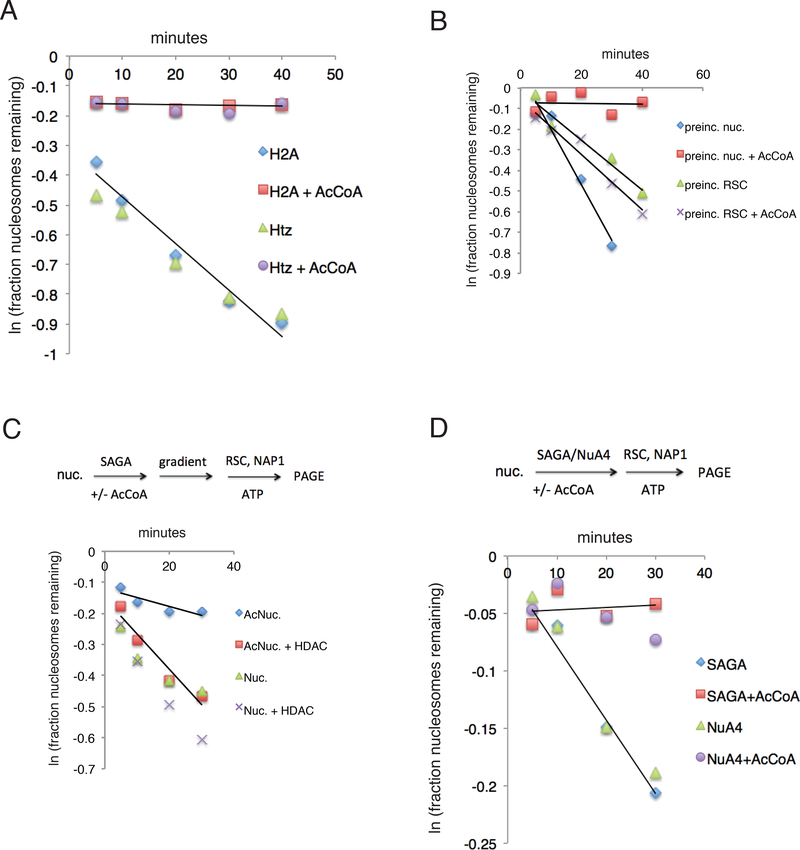

We investigated the effect of histone acetylation by SAGA upon RSC activity. Whereas acetylation has been thought to enhance chromatin remodeling, we found that SAGA and acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) prevented the transfer of histones to the NAP1 chaperone protein by RSC and ATP (Figures 1A, S1). In the absence of acetyl-CoA, SAGA had no effect upon histone transfer. Since RSC itself is a target of acetylation by Gcn5 (VanDemark et al., 2007), we wondered whether inhibition of histone transfer by SAGA and acetyl-CoA is due to acetylation of RSC or of the nucleosome. We addressed the question by preincubation of either RSC or the nucleosome with SAGA and acetyl-CoA, followed by assay of histone transfer. Preincubation was terminated by addition of an amount of chromatin sufficient to adsorb SAGA and stop the acetylation reaction but not to affect the larger amount of RSC in the experiment. The result was clearcut: pretreatment of nucleosomes was inhibitory to histone transfer, whereas preincubation of RSC was without effect (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Inhibition of RSC Activity by SAGA and Acetyl-CoA.

(A) Nucleosome disassembly (conversion to naked DNA) in reactions with RSC, NAP1, and ATP, in the presence (red squares) or absence (blue diamonds) of SAGA and acetyl-CoA.

(B) Nucleosome disassembly in reactions with RSC, NAP1, and ATP, following preincubation of nucleosomes with (red squares) or without SAGA and acetyl-CoA, or preincubation of RSC with (x’s) or without (green triangles) RSC and ATP.

(C) Nucleosome disassembly in reactions with RSC, NAP1, and ATP. Nucleosomes were treated with SAGA and acetyl-CoA (red squares, blue diamonds) or not (x’s, green triangles) and reisolated by gradient sedimentation before the experiment. Nucleosomes were preincubated for 30 min at 30 °C w ith 0.5 μg of HDAC6 (red squares, x’s) or not (blue diamonds, green triangles) before the addition of RSC and ATP.

This result was confirmed by gradient sedimentation of nucleosomes following treatment with SAGA and acetyl-CoA. SAGA was removed by binding to high molecular weight DNA, which sedimented to the bottom of the gradient. Nucleosomes sedimented at the same rate before and after acetylation, so the structure of the nucleosome was little if at all affected by the procedure, but histone transfer from nucleosomes to NAP1 by RSC and ATP was inhibited by acetylation (Figure 1C).

Further evidence that inhibition was due to histone acetylation came from the reversal of inhibition by treatment with histone deacetylase. Nucleosomes isolated following acetylation by SAGA and acetyl-CoA, and subsequently treated with HDAC6, underwent histone transfer by RSC and ATP at the same rate as control nucleosomes, exposed to neither SAGA and acetyl-CoA nor to HDAC6 (Figure 1C).

The +1 nucleosome of yeast genes differs from most others by the substitution of H2A with the variant Htz1 (Zhang et al., 2005; Raisner et al., 2005). This substitution may be destabilizing, because Htz1 is dissociable from yeast chromatin at a much lower ionic strength than H2A (Zhang et al., 2005). It may be asked whether Htz1 relieves the inhibitory effect of acetylation upon histone transfer by RSC and ATP. Nucleosomes containing either H2A or Htz1 were therefore compared, and no difference in the inhibitory effect of acetylation was observed (Figure 1A).

We also investigated the effect of histone acetylation by NuA4 upon RSC activity. NuA4 and acetyl CoA prevented the transfer of histones to NAP1 by RSC and ATP, similarly to SAGA; NuA4 alone was not inhibitory (Figure 1D). Acetylation by NuA4 may also serve to regulate RSC activity, in transcription or another context.

Basis for inhibition of RSC activity by acetylation

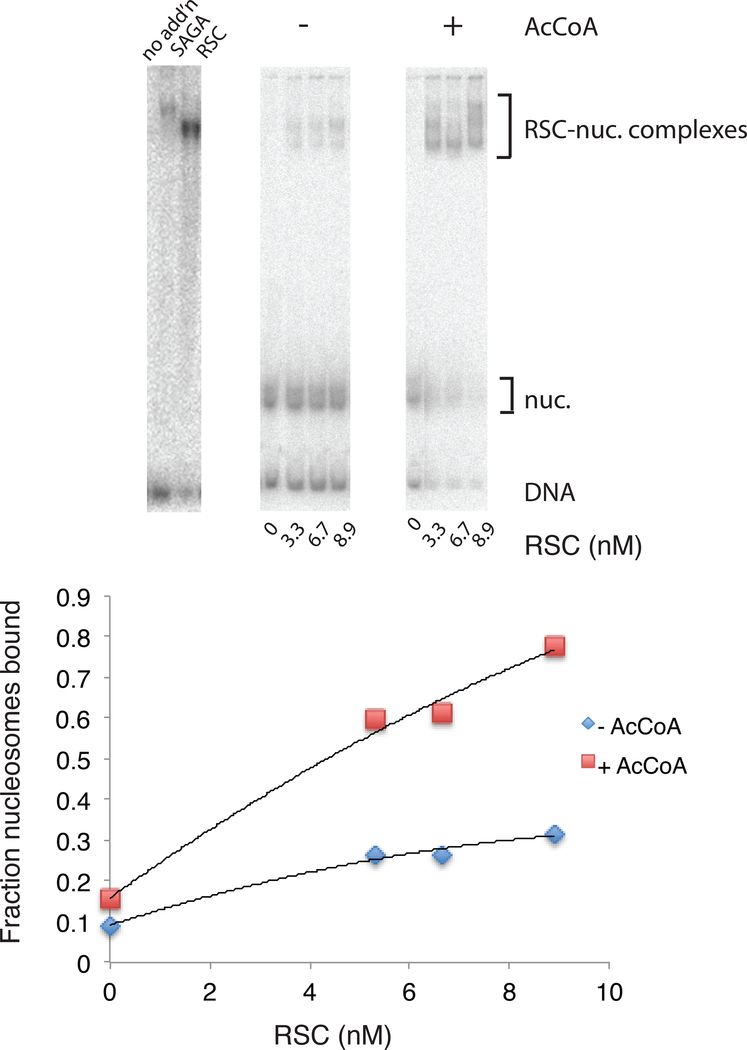

It has been reported that RSC binding to a nucleosome, revealed by an electrophoretic mobility shift of the nucleosome, is enhanced in the presence of SAGA and acetyl-CoA (Carey et al., 2006). We observed that SAGA alone produces a similar mobility shift (Figure 2), raising the question of whether the reported shift was due to RSC or SAGA. To answer the question, we isolated nucleosomes following treatment with SAGA and acetyl-CoA, as described above. We found an enhanced mobility shift of the isolated, acetylated nucleosomes, compared with nucleosomes treated in the same manner but without acetyl-CoA (Figure 2). Half-saturation of RSC with acetylated nucleosomes occurred at about 5 nM RSC, pointing to an affinity constant of about 0.5 × 109 M−1 for the interaction (Figure 2). Half saturation of unacetylated nucleosomes was not achieved..

Figure 2. Enhancement of RSC-Nucleosome Interaction by SAGA and Acetyl-CoA.

Nucleosomes were treated with SAGA and acetyl-CoA (upper middle panel, plotted as red squares in lower panel) or not (upper right panel, plotted as blue diamonds in lower panel) and reisolated by gradient sedimentation. Electrophoretic mobility shift experiments were preformed by the same procedure as for nucleosome disassembly reactions, except with the concentrations of RSC indicated, no NAP1, incubation for 15 min, and no salmon sperm DNA added before electrophoresis. Optical densities were integrated over bands in PhosphorImager scans (brackets, upper panels) for calculations (lower panel). In a separate electrophoretic mobility shift experiment (upper left panel), SAGA (0.36 μg) or RSC (0.08 μg) were combined with untreated nucleosomes under the same conditions.

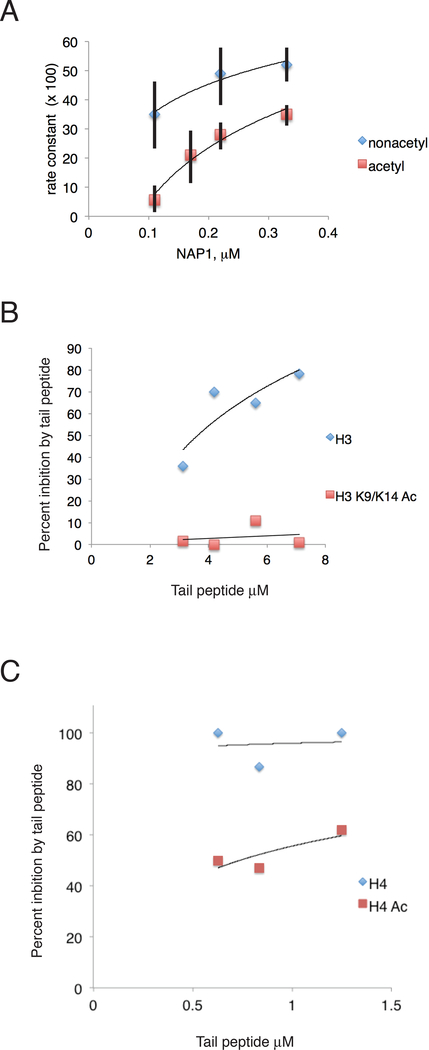

The increase in affinity of RSC for the histone octamer due to acetylation can partially account for the inhibition of removal of the octamer, but the increase is not great enough to explain the full extent of inhibition. The other component of the reaction, NAP1, has also been shown to interact with histone tails (McBryant et al., 2003). We investigated whether histone acetylation affects the function of NAP1 in octamer transfer. To this end, we compared the dependence on NAP1 concentration of rate of transfer of acetylated and unacetylated histone octamers. We found a strong dependence for acetylated octamers, with the rate of transfer rising nearly 10-fold upon increase of NAP1 concentration from 0.1 to 0.3 mM (Figure 3A), which might be explained by a requirement for two molecules of NAP1 for transfer in two steps of H2A/H2B and of H3/H4 (Lorch et al., 2006), and thus dependence on the square of the NAP1 concentration. By contrast, there was only a slight dependence of the transfer rate for unacetylated octamers, rising about 1.5-fold over the same concentration range, indicative of NAP1 nearly saturating at these concentrations. Evidently, histone acetylation diminishes the affinity and thus the rate of transfer of histones to NAP1.

Figure 3. Effect of Acetylation on NAP1 Dependence of Nucleosome Disassembly by RSC.

(A) Nucleosomes were treated with SAGA and acetyl-CoA (upper middle panel, red squares) or not (upper right panel, blue diamonds) and reisolated by gradient sedimentation. Disassembly reactions were performed with the concentrations of NAP1 indicated. Apparent first order rate constants (units of min−1, multiplied by −1) were determined from plots such as Fig. 1. Error bars represent standard deviations determined from three technical replicates.

(B) Nucleosome disassembly as in Fig. 1, in the presence of H3 tail peptide (blue diamonds) or doubly acetylated H3 tail peptide (red squares).

(C) Nucleosome disassembly as in Fig. 1, in the presence of H4 tail peptide (blue diamonds) or acetylated H4 tail peptide (red squares).

Another line of evidence for a role of histone tails in the transfer of histones to NAP1, and for an effect of acetylation on the affinity of histone-NAP1 interaction, came from competition with tail peptides (Figure 3B). An H3 tail peptide, residues 1–21, and an H4 tail peptide, residues 1–20, inhibited histone octamer transfer (Figures 3B, 3C). Inhibition was completely relieved by acetylation of residues K9 and K14 of the H3 peptide, and partially relieved by acetylation of residue K16 of the H4 peptide. Transfer evidently depends on an interaction with the histone tails, which is prevented by lysine acetylation.

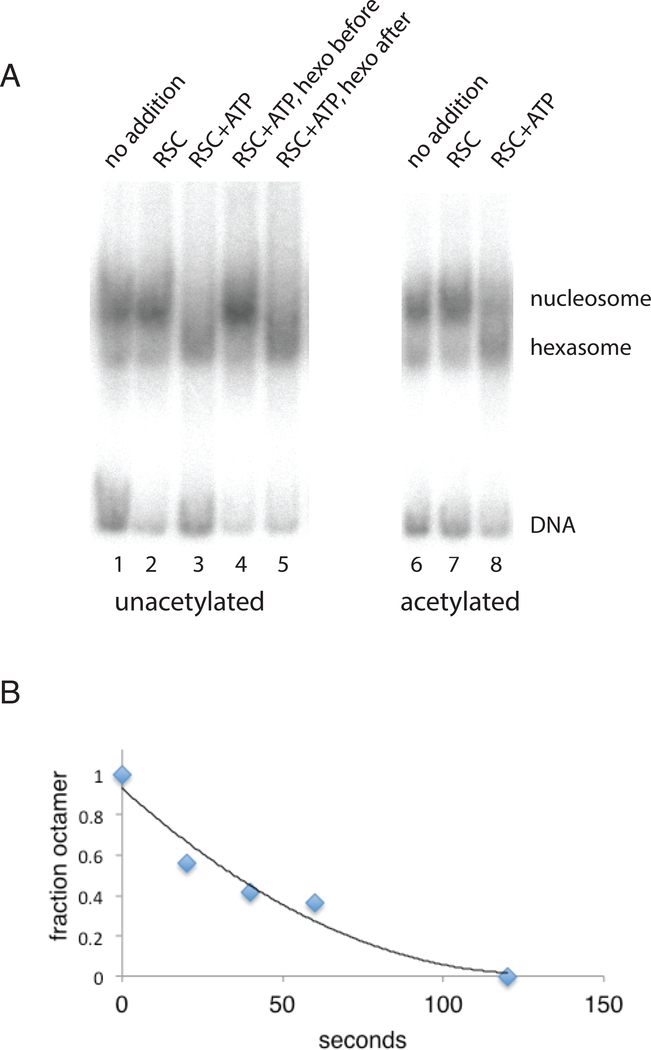

Conversion to a hexamer-nucleosome

Partial unwrapping of DNA from the +1 nucleosome of transcriptionally active promoters may be due to the displacement or loss of an H2A-H2B dimer, as noted above (see Introduction). We observed the conversion of a nucleosome to a faster migrating form, possibly due to such histone loss, upon treatment with RSC and ATP; the reaction proceeded no further in the absence of NAP1 (Figure 4A). The reaction was rapid, complete in about a minute (Figure 4B). Inasmuch as the reaction was terminated by the addition of excess DNA, the question arises whether histones were dislodged by RSC and ATP but still associated with the nucleosome, and removed by the DNA. If only dislodged but not fully displaced, the histones might reassociate following removal of ATP. We found, however, that the reaction was irreversible; the faster migrating form persisted following treatment with hexokinase and glucose to remove ATP (Figure 4A). Of particular significance for the present study, the reaction occurred at the same rate and was similarly irreversible for nucleosomes acetylated with SAGA and acetyl-CoA as for unacetylated nucleosomes (Figure 4A and data not shown).

Figure 4. Conversion of Octamer to Hexamer Nucleosome.

(A) Irreversible conversion of octamer to hexamer nucleosome (hexasome), unaffected by acetylation with SAGA and acetyl-CoA. Reactions were performed as for Fig. 1, except in the absence of NAP1, with incubation for 20 min at 30 °C with no RSC and no ATP (lanes 1, 6), with RSC only (lanes 2, 7), and with RSC and ATP (lanes 3, 8). To test reversibility, hexokinase (1.25 μg) and glucose (0.3 micromoles) were added after 10 min of incubation (lane 5), and to confirm that this treatment destroyed all ATP, hexokinase and glucose were added at the beginning and RSC only added after 10 min of incubation (lane 4). Reactions were performed with nucleosomes pretreated with SAGA and acetyl-CoA (lanes 6–8) or not (lanes 1–5).

(B) Time course of conversion of octamer to hexasome by RSC and ATP. A reaction mixture identical to that in lane 3 in part (A) was incubated for 0, 20, 40, 60, and 120 sec, and optical densities were integrated over bands in PhosphorImager scans for nucleosomes and hexasomes.

Conversion of the nucleosome to a faster migrating particle, due to the loss of an H2A-H2B dimer, has been observed upon transcription in vitro and in vivo (Kireeva et al., 2002); Belotserkovskaya et al., 2003). The faster migrating particle was identified as a hexamer nucleosome, or hexasome, by comparison of electrophoretic mobility with a reconstituted hexasome. Evidence for a hexasome at the +1 position in vivo was obtained by digestion with micrococcal nuclease, which gave rise to DNA fragments of 112, 103, and 90 bp (Ramachandran et al., 2017). These fragments were centered on one side or the other of the dyad of the +1 nucleosome, as expected for the unwrapping of DNA from one side, due to loss of an H2A-H2B dimer in a hexasome. By contrast, a fragment of 68 bp would result from the loss of two H2A-H2B dimers in a tetrasome (Li and Wang, 2012). We performed micrococcal nuclease digestion of nucleosomes following treatment with RSC and ATP, and found fragments of 109, 98, and 88 +/− 2 bp (Figure S2). These fragments clearly correspond with those derived from +1 nucleosomes, with a periodicity of 10 bp as observed in all studies on nuclease digestion of nucleosomal DNA. Minor differences in size between our results and those for +1 nucleosomes may be attributed to the difference in experimental design (unique fragments arising from digestion of a single nucleosome, versus a broad distribution of fragments arising from digestion of +1 nucleosomes genome-wide), and to the sequence preference of micrococcal nuclease (manifest in the digestion of a single nucleosome). We further identified the fast migrating particle produced by RSC and ATP as a hexasome rather than a tetrasome by elution of the particle from the gel, SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting with anti-H2A antibody, revealing the level of H2A expected for a hexasome (half that of a nucleosome).

DISCUSSION

Hallmarks of the +1 nucleosome of most yeast genes in vivo include a persistent association with RSC and a partial loss of association with H2A and H2B (Ramachandran et al., 2015; Rhee et al., 2014). The question arises why RSC, which transfers all histones from nucleosomes to a chaperone in the presence of ATP in vitro, fails to fully disrupt the +1 nucleosome in vivo. Here we show that histone acetylation by the SAGA complex and acetyl-CoA, known to occur at +1 nucleosomes of transcribed genes, inhibits the disruption of nucleosomes by RSC and ATP. Acetylation is permissive for the displacement of an H2A-H2B dimer by RSC and ATP, but prevents further disassembly.

Loss of the histone acetyl transferase activity of SAGA has only a small effect on transcription in yeast in vivo (Huisinga and Pugh, 2004), which may be explained by redundancy, due to the action of NuA4. Although not shown to play a role in transcription in wild type yeast, acetylation by NuA4 inhibits histone octamer transfer by RSC to NAP1 in vitro (Fig. 1D). Moreover, the H4 tail, principal target of acetylation by NuA4, interferes with histone-NAP1 interaction in an acetylation-dependent manner (Fig. 3C).

The effect of acetylation on histone transfer by RSC may be explained by two factors, the enhancement of RSC-histone interaction, and the inhibition of NAP1-histone interaction. Both factors may contribute to the persistence of RSC at the +1 nucleosome. Enhancement of RSC-histone interaction by acetylation, likely due to the occurrence of mutiple bromodomains in RSC subunits, will increase the lifetime of RSC bound to the +1 nucleosome. The inhibition of transfer to NAP1 is relevant because of a reported role of NAP1 in transcriptional activation in vivo (Ito et al., 2000; Walter et al., 1995). Transcriptional activation involves the removal of nucleosomes by RSC (Hartley and Madhani, 2009), and NAP1 may be a histone acceptor in this process. Inhibition of NAP1 would prevent removal of the +1 nucleosome.

Acetylation by SAGA is especially pertinent to the +1 nucleosome in light of recent evidence for the generality of SAGA activity. SAGA is associated with the UAS elements of most yeast genes, and is likely recruited by Mediator (Baptista et al., 2017). Results of mutation and subunit depletion show that SAGA is required for transcription of virtually all genes in vivo (Baptista et al., 2017). SAGA is also required for transcription in vitro of chromatin assembled in vivo (Nagai et al., 2017). SAGA binds trimethylated H3K4 (Bian et al., 2011), a histone mark characteristic of +1 nucleosomes (Bernstein et al., 2002; Ng et al., 2003), so SAGA is likely associated with the +1 nucleosome and responsible for its acetylation. That SAGA is required for transcription may be due, at least in part, to the role of acetylation in the interaction of RSC with the +1 nucleosome and in regulating RSC activity.

By treatment of nucleosomes with SAGA and acetyl-CoA, and with RSC and ATP, we have recapitulated the salient features of the +1 nucleosome, namely, the persistent interaction with RSC and perturbation of H2A-H2B dimer interaction. Additional features of the +1 nucleosome include the replacement of H2A by Htz1, which may also relate to the perturbation of dimer interaction. Ultimately, the +1 nucleosome must be removed for transcription, and it remains to be determined whether RSC or other factors are involved.

STAR Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the Lead Contact (Dr. Yahli Lorch (lorch@stanford.edu).

METHOD DETAILS

Nucleosomes were assembled with rat liver histones as described below, with the use of 160 bp DNA labeled with 32P at one 5’- end by PCR, except for Fig. 1A, in which nucleosomes we assembled with recombinant yeast histones, as described below. Nucleosome disassembly reactions contained nucleosomes (1 ng DNA), RSC (160 ng), NAP1 (250 ng), 0.5 mM ATP, 15 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, in a total volume of 15 μl. Following incubation at 30°C for the times indi cated, 0.8 μg of salmon sperm DNA was added to disrupt RSC-nucleosome complexes, and reaction products were separated by electrophoresis in 3.2% polyacrylamide gel (19:1 acrylamide:bisacrylamide) in TE. Optical densities were integrated over bands in PhosphorImager scans for calculations of nucleosome disassembly rates. All experiments were repeated three or more times, with standard deviations indicated where appropriate.

Preincubation with SAGA (27 nM) and acetyl-CoA (66 μM) was performed for 30 min at 30 °C before the addition of either RSC or nucleoso mes to disassembly reactions. Pretreatment of nucleosomes followed by reisolation was performed by incubation of nucleosomes (225 ng DNA) with SAGA (65 ng) and acetyl-CoA (50 μM) in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 33 μg/ml BSA, 1 mM MgCl2 for 45 min at 30 °C, followed by the addition of 30 μg of bacterial plasmid DNA and sedimentation in a 5–30% maltose gradient as described.

Nucleosomes (rat liver histones, cf. Lorch et al., 2005)

A 160 bp fragment of the Xenopus 5S gene DNA, 5’-end labeled as described above (16 μl of 85 ng/μl), was combined with 11.5 μl of 2.5 mg/ml rat liver chromatin (depleted of histone H1 by filtration through Sepharose 4B in 0.45 M NaCl), 19 μl of 5 M NaCl, 0.5 μl of 0.1 M NaHSO3, and 4.3 μl H2O. The mixture was diluted with 33 μl, 41.8 μl, and 208 μl of 25 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 1 mM NaHSO3, with incubation for 10 min at 30 °C after each dilution, followed by sedimentation in a 5–30% maltose gradient (11ml) containing 25 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 0.2 mg/ml BSA, 10 mM NaHSO3, 1 mM EDTA in a Thermo Scientific TH-641 rotor at 35,000 rpm for 16 h.

Nucleosomes (yeast histones)

Yeast histone genes in pET vectors (gift of Bradley Cairns, University of Utah) were introduced in BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL competent E. coli cells (Agilent cat. no. 230280), grown (1 l) to an OD600 of 0.8, induced with 0.2 M IPTG at 37° C for 2 h ( H3 and H4) and 3 h (H2A and H2B), harvested, washed with water and frozen. Pellets (approximately 8 g) were suspended in 40 ml of 7 M guanidine, 50 mM HEPES ph 7.5, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitors (2 μM pepstatin A, 0.6 μM leupeptin, 2 mM benzamidine, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), sonicated (Misonix Sonicator, amplitude 40) on ice for three periods of 10 sec, with cooling periods of 90 sec between, and centrifuged in a Beckman 45 Ti rotor at 42,000 rpm for 45 min. The supernatant (about 55 ml) was loaded on a Sephadex G-25 column (275 ml) in SAU 250 buffer (40 mM sodium acetate pH 5.2, 7 M urea, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM lysine, 250 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitors), followed by 250 ml of 6 M guanidine and 500 ml of H2O. Pooled protein fractions were passed through a Q Sepharose Fast Flow column (20 ml; GE Healthcare Life Sciences) in SAU 250 buffer and pooled protein fractions were applied to a Hitrap SP column (5 ml; GE Healthcare Life Sciences) in SAU 250 buffer, washed with SAU 300 buffer, and eluted with a gradient of SAU 300–600 buffer. Peak histone fractions were concentrated with a Vivaspin 6 Centrifugal Concentrator (Vivaspin Products) at 4000 rpm in a clinical centrifuge to a concentration of 3.4 mg/ml, dialyzed against H2O, and lyophilized.

Each lyophilized yeast histone (1 mg) dissolved in 400 ml of 7 M guanidine, 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM diththiothreitol, during 30 min at room temperature. Concentrations were determined from A280 values, and equimolar amounts of the four histones were combined, dialyzed in SnakeSkin dialysis tubing, 7K MWCO (ThermoFisher Scientific cat. no. 68100) three times against against 1 l of 2M NaCl, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 15 mM β-mercaptoethanol, clarified in a microfuge at 14,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, filtered through a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) in 2M NaCl, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 15 mM β-mercaptoethanol, concentrated in a Vivaspin 2 Centrifugal Concentrator to 0.88 mg/ml, and adjusted by the addition of 100% glycerol to a final concentration of 10%.

The resulting histone octamer preparation (4.99 μl of 1.56 mg/ml in 1.6 M NaCl), was mixed with 8.4 μl of 32P-labeled DNA (835 ng/μl, see above), 6.4 ml of 5 M NaCl, and 0.2 ml H2O, pipetted into a Pierce Slide-A-Lyzer MINI Dialysis Unit (Thermo Scientific cat. no. 69850), placed in an Econo-Column (Bio-Rad) with 500 ml of 2M KCl, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, followed by 1.5 l of 0.25 M KCl, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA at 1 ml/min, and dialyzed against 500 ml of the same buffer for 2 h. The dialysate was sedimented in a 5–30% maltose gradient in 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 10 mM NaHSO3, 1 mM EDTA in a Beckman SW 60 Ti rotor at 55,000 rpm for 6 h.

RSC and SAGA preparation (cf. Lorch and Kornberg, 2003)

An S. cerevisiae strain bearing a TAP-tag on the Rsc2 subunit was grown to late log phase, and the cell pellet was suspended in an equal volume of lysis buffer (0.4 M HEPES pH 7.4, 4 mM EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol, protease inhibitors at twice the concentrations listed above, 20% glycerol), frozen, thawed, centrifuged in a Beckman J-LITE Fixed Angle Aluminum JLA 8.1000 rotor at 6000 rpm for 20 min. The cells were resuspended in an equal volume of 0.5x lysis buffer and disrupted in a DYNO-MILL, followed by PEI precipitation (adjusted to 200 mM ammonium sulfate, adjusted to a final concentration of 0.35% PEI by the addition of 5% PEI, centrifuged in a Beckman JA-10 Fixed Angle rotor at 10,000 rpm for 45 min) and ammonium sulfate precipitation (addition of an equal volume of saturated ammonium sulfate to the PEI supernatant during 10 min with stirring, a further 45 min of stirring, and centrifugation in the Beckman JLA 8.1000 rotor (see above) at 8000 rpm for 30 min). The ammonium sulfate precipitate was dissolved in sufficient 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 0.2 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, protease inhibitors to reduce the conductivity lower than that of 500 mM ammonium sulfate, applied to a column of IgG Sepharose 6 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare cat. no. 17–0969-01) in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 200 mM ammonium sulfate, 2 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, washed with ten column volumes of the same buffer containing 2 mM dithiothreitol and 2x protease inhibitors, washed with ten column volumes of 50 mM RSC buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 50 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.01% NP-40), and eluted by incubation with 1.5 column volumes of TEV protease in 50 mM RSC buffer overnight at 4 °C. RS C fractions were applied to an UNO Q1 column (20 ml, Bio-Rad) in 50 mM RSC buffer, washed with 100 mM RSC buffer, and eluted with a gradient of 0.1–1 M RSC buffer.

SAGA was prepared by a similar procedure from an S. cerevisiae strain bearing a TAP-tag on Spt7.

NAP1 preparation

The gene for yeast NAP1 bearing a His-tag in pET28 was introduced in BL21(DE3)pLysS competent cells (Promega, cat. no. L1195). A 2 l culture was induced with 2 ml of 1 M IPTG for 5 h, harvested by centrifugation in the Beckman JLA 8.1000 rotor (see above) at 6000 rpm for 15 min, resuspended in 50 ml of Talon buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.6, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% NP40, 0.5x protease inhibitors, 10% glycerol), frozen, thawed, supplemented with another 0.5x protease inhibitors, solubilized by passage through a French pressure cell, and centrifuged in a Beckman 70 Ti rotor at 50,000 rpm for 30 min. The supernatant was allowed to bind to 5 ml of Talon beads (equilibrated in Talon buffer) for 1 h at 4 °C, washed in a column with te n column volumes of 40 mM imidazole in Talon buffer, and eluted with three column volumes of 250 mM imidazole in Talon buffer.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Standard deviations were computed with Excel (Microsoft) from three technical replicates.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Histone acetylation prevents histone octamer transfer by RSC to the chaperone NAP1

Histone acetylation enhances RSC-nucleosome and diminishes histone-NAP1 interactions

RSC and ATP dislodge an H2A-H2B dimer from the nucleosome, with or without acetylation

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Ralph Davis for a gift of NuA4. This research was supported by NIH grant GM36659.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Allard S, Utley RT, Savard J, Clarke A, Grant P, Brandl CJ, Pillus L, Workman JL, and Cote J (1999). NuA4, an essential transcription adaptor/histone H4 acetyltransferase complex containing Esa1p and the ATM-related cofactor Tra1p. EMBO J 18, 5108–5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista T, Grunberg S, Minoungou N, Koster MJE, Timmers HTM, Hahn S, Devys D, and Tora L (2017). SAGA Is a General Cofactor for RNA Polymerase II Transcription. Mol Cell 68, 130–143 e135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belotserkovskaya R, Oh S, Bondarenko VA, Orphanides G, Studitsky VM, and Reinberg D (2003). FACT facilitates transcription-dependent nucleosome alteration. Science 301, 1090–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Humphrey EL, Erlich RL, Schneider R, Bouman P, Liu JS, Kouzarides T, and Schreiber SL (2002). Methylation of histone H3 Lys 4 in coding regions of active genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 8695–8700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian C, Xu C, Ruan J, Lee KK, Burke TL, Tempel W, Barsyte D, Li J, Wu M, Zhou BO, et al. (2011). Sgf29 binds histone H3K4me2/3 and is required for SAGA complex recruitment and histone H3 acetylation. EMBO J 30, 2829–2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreault AA, Cronier D, Selleck W, Lacoste N, Utley RT, Allard S, Savard J, Lane WS, Tan S, and Cote J (2003). Yeast enhancer of polycomb defines global Esa1-dependent acetylation of chromatin. Genes Dev 17, 1415–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns BR, Lorch Y, Li Y, Zhang M, Lacomis L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Du J, Laurent B, and Kornberg RD (1996). RSC, an essential, abundant chromatin-remodeling complex. Cell 87, 1249–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey M, Li B, and Workman JL (2006). RSC exploits histone acetylation to abrogate the nucleosomal block to RNA polymerase II elongation. Mol Cell 24, 481–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaban Y, Ezeokonkwo C, Chung WH, Zhang F, Kornberg RD, Maier-Davis B, Lorch Y, and Asturias FJ (2008). Structure of a RSC-nucleosome complex and insights into chromatin remodeling. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15, 1272–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AS, Lowell JE, Jacobson SJ, and Pillus L (1999). Esa1p is an essential histone acetyltransferase required for cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol 19, 2515–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, and Grunstein M (1988). Nucleosome loss activates yeast downstream promoters in vivo. Cell 55, 1137–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley PD, and Madhani HD (2009). Mechanisms that specify promoter nucleosome location and identity. Cell 137, 445–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisinga KL, and Pugh BF (2004). A genome-wide housekeeping role for TFIID and a highly regulated stress-related role for SAGA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell 13, 573–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Ikehara T, Nakagawa T, Kraus WL, and Muramatsu M (2000). p300-mediated acetylation facilitates the transfer of histone H2A-H2B dimers from nucleosomes to a histone chaperone. Genes Dev 14, 1899–1907. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kireeva ML, Walter W, Tchernajenko V, Bondarenko V, Kashlev M, and Studitsky VM (2002). Nucleosome remodeling induced by RNA polymerase II: loss of the H2A/H2B dimer during transcription. Mol Cell 9, 541–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krietenstein N, Wal M, Watanabe S, Park B, Peterson CL, Pugh BF, and Korber P (2016). Genomic Nucleosome Organization Reconstituted with Pure Proteins. Cell 167, 709–721 e712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MH, Zhou J, Jambeck P, Churchill ME, and Allis CD (1998). Histone acetyltransferase activity of yeast Gcn5p is required for the activation of target genes in vivo. Genes Dev 12, 627–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo YM, Henry RA, Tan S, Cote J, and Andrews AJ (2015). Site specificity analysis of Piccolo NuA4-mediated acetylation for different histone complexes. Biochem J 472, 239–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, and Wang MD (2012). Unzipping single DNA molecules to study nucleosome structure and dynamics. Methods in enzymology 513, 29–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, Cairns BR, Zhang M, and Kornberg RD (1998). Activated RSC-nucleosome complex and persistently altered form of the nucleosome. Cell 94, 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, Davis B, and Kornberg RD (2005). Chromatin remodeling by DNA bending, not twisting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 1329–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, Griesenbeck J, Boeger H, Maier-Davis B, and Kornberg RD (2011). Selective removal of promoter nucleosomes by the RSC chromatin-remodeling complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18, 881–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, and Kornberg RD (2003). Isolation and Assay of the RSC Chromatin-Remodeling Complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods in enzymology 377, 316–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, LaPointe JW, and Kornberg RD (1987). Nucleosomes inhibit the initiation of transcription but allow chain elongation with the displacement of histones. Cell 49, 203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, Maier-Davis B, and Kornberg RD (2006). Chromatin remodeling by nucleosome disassembly in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 3090–3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, Maier-Davis B, and Kornberg RD (2010). Mechanism of chromatin remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 3458–3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, Zhang M, and Kornberg RD (1999). Histone octamer transfer by a chromatin-remodeling complex. Cell 96, 389–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBryant SJ, Park YJ, Abernathy SM, Laybourn PJ, Nyborg JK, and Luger K (2003). Preferential binding of the histone (H3-H4)2 tetramer by NAP1 is mediated by the amino-terminal histone tails. J Biol Chem 278, 44574–44583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai S, Davis RE, Mattei PJ, Eagen KP, and Kornberg RD (2017). Chromatin potentiates transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 1536–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng HH, Robert F, Young RA, and Struhl K (2002). Genome-wide location and regulated recruitment of the RSC nucleosome-remodeling complex. Genes Dev 16, 806–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng HH, Robert F, Young RA, and Struhl K (2003). Targeted recruitment of Set1 histone methylase by elongating Pol II provides a localized mark and memory of recent transcriptional activity. Mol Cell 11, 709–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raisner RM, Hartley PD, Meneghini MD, Bao MZ, Liu CL, Schreiber SL, Rando OJ, and Madhani HD (2005). Histone variant H2A.Z marks the 5’ ends of both active and inactive genes in euchromatin. Cell 123, 233–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran S, Ahmad K, and Henikoff S (2017). Transcription and Remodeling Produce Asymmetrically Unwrapped Nucleosomal Intermediates. Mol Cell 68, 1038–1053 e1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran S, Zentner GE, and Henikoff S (2015). Asymmetric nucleosomes flank promoters in the budding yeast genome. Genome research 25, 381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke H, and Horz W (2003). Histones are first hyperacetylated and then lose contact with the activated PHO5 promoter. Mol Cell 11, 1599–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee HS, Bataille AR, Zhang L, and Pugh BF (2014). Subnucleosomal structures and nucleosome asymmetry across a genome. Cell 159, 1377–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee HS, and Pugh BF (2012). Genome-wide structure and organization of eukaryotic preinitiation complexes. Nature 483, 295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha A, Wittmeyer J, and Cairns BR (2002). Chromatin remodeling by RSC involves ATP-dependent DNA translocation. Genes Dev 16, 2120–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ER, Eisen A, Gu W, Sattah M, Pannuti A, Zhou J, Cook RG, Lucchesi JC, and Allis CD (1998). ESA1 is a histone acetyltransferase that is essential for growth in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 3561–3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern M, Jensen R, and Herskowitz I (1984). Five SWI genes are required for expression of the HO gene in yeast. J Mol Biol 178, 853–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanDemark AP, Kasten MM, Ferris E, Heroux A, Hill CP, and Cairns BR (2007). Autoregulation of the rsc4 tandem bromodomain by gcn5 acetylation. Mol Cell 27, 817–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter PP, Owen-Hughes TA, Cote J, and Workman JL (1995). Stimulation of transcription factor binding and histone displacement by nucleosome assembly protein 1 and nucleoplasmin requires disruption of the histone octamer. Mol Cell Biol 15, 6178–6187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan GC, Liu YJ, Dion MF, Slack MD, Wu LF, Altschuler SJ, and Rando OJ (2005). Genome-scale identification of nucleosome positions in S. cerevisiae. Science 309, 626–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Roberts DN, and Cairns BR (2005). Genome-wide dynamics of Htz1, a histone H2A variant that poises repressed/basal promoters for activation through histone loss. Cell 123, 219–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zofall M, Persinger J, Kassabov SR, and Bartholomew B (2006). Chromatin remodeling by ISW2 and SWI/SNF requires DNA translocation inside the nucleosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13, 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.