Abstract

As the challenge of proper reporting of potential financial conflicts of interest is once again brought into the national spotlight, this editorial considers the recent events, expands on current systems for enforcing accurate reporting of financial disclosures, and considers ways to move forward.

A dramatic and totally unexpected series of events has thrown the problem of conflict of interest (COI) in cancer trials onto the national stage, and is likely to have repercussions for researchers, drug companies, journals, and indeed the whole enterprise of cancer drug development. On Sept. 7, 2018, the New York Times reported that Jose Baselga, the Physician‐in‐Chief at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) and one of the most prominent cancer researchers of the past decade, failed to acknowledge extensive ties to industry in high profile articles he published in The New England Journal of Medicine, The Lancet, and elsewhere [1]. His ties to industry were not trivial: a seat on the board of directors at Bristol‐Myers Squibb and at Varian, and a highly paid consultancy to Hoffman‐La Roche, Genentech, and numerous other companies. In some cases, the articles were about drugs owned by companies with which he had strong financial ties. The subject of COI has particular importance in reports of drug evaluation, where the results will influence the choice of treatment for cancer patients. Failure to disclose important ties casts a shadow on otherwise valuable research. Dr. Baselga resigned his position at MSKCC a few days later [2].

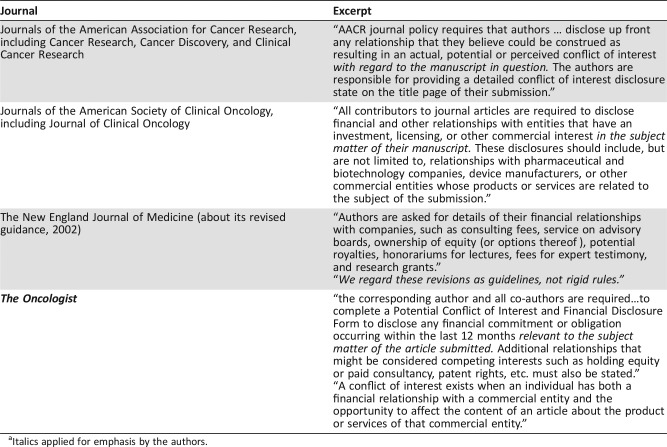

In a letter to MSKCC faculty, Craig Thompson, President, urged compliance with rules about COI and disclosure [3]. However, perhaps mitigating the transgression, he called attention to the “nebulous” guidelines for reporting COI and noted the lack of a common standard among journals for reporting COI. Thompson is at least partially correct (Table 1). Authors are confused as to what industry relationships are pertinent. Are they expected to report only those ties to industries that own the drug(s) under discussion; should ties to industries that have competitive compounds be disclosed as well? Are all financial interests in pharma, biotech, and related companies pertinent and reportable, no matter how unrelated they are to the subject of the paper under consideration? It seems self‐evident that a financial relationship with a company that owns the drug that is the subject of the paper, or a competitor of that drug, is an obvious reportable conflict of interest, and must be disclosed. That Dr. Baselga, a journal editor in his own right, failed to make such a disclosure of clearly pertinent relationships in key articles is disturbing and disappointing.

Table 1. Conflict of Interest Reporting Instructions for Selected Journalsa .

Italics applied for emphasis by the authors.

As reflected in Table 1, the disclosure required by one journal may be restricted to activity related directly to the subject of the proposed publication (ASCO and AACR journals), or may be very open ended, and indeed “not rigid” as per The New England Journal of Medicine. The time period covered by the disclosure of COIs varies as well. A lot is left to the author's discretion. One might question the need to disclose financial ties to preclinical start‐up companies, unrelated to the drug or trial in question, and without a commercial product. How deeply to delve into more tangential relationships (stock ownership or consulting in early biotech companies unrelated to the publication, for example) is unclear, and therefore a matter of personal judgment. Erring on the side of more rather than less disclosure is undoubtedly the safest practice, but journals and academic organizations must develop clearer definitions of what constitutes a reportable financial relationship, and harmonize those definitions.

There is no well‐established system for enforcement of financial disclosure related to conflict of interest. A federal database, “Open Payments”, contains information on payments to academic researchers made by companies with FDA‐approved products, but this system does not apply to authors from Europe or other parts of the world. To our knowledge, journals do not routinely check their authors' reported COIs against the Open Payments database. A second site (www.convey.org) contains COI information filed by individual researchers, and is freely accessible online, but has no official standing among publications. This most recent episode highlights the problem of verifying COI. Unless an outside person, such as a journal editor, a reporter, a reader, or a grant reviewer, makes the effort to search this database, the information on COI provided by authors is accepted at face value, and will go unchecked.

What will be the ramifications of this episode? It will surely increase the general level of skepticism about cancer research, and its “breakthroughs”, and will add credibility to those who doubt that real progress is being made in cancer treatment. If additional important instances of failure to report COI surface, such episodes could dampen the enthusiasm for rapid approval of new treatments based on single trials and reverse years of progress in speeding drug approval at the Food and Drug Administration. This episode will encourage those who want to construct higher barriers between academia and industry, a relationship essential to the development of new drugs for cancer patients. Marcia Angell, 18 years ago an editor of The New England Journal of Medicine, has reiterated her call for a total ban on financial ties between researchers and companies [4], a stance that would undoubtedly impact the quality and pace of new drug development and apply brakes to the drug approval process. To our mind, such extreme strictures would be harmful to progress in cancer treatment. Academic physicians offer invaluable advice to companies regarding clinical trial design, potential paths to drug approval, and strategies for recruiting patients to clinical trials. With good academic advice, companies may avoid pitfalls that can lead to premature discontinuation of drug development. Clearly, the role of these advisors must be identified in their publications. Beyond disclosure, there are unresolved questions as to whether researchers who accept personal remuneration from a company should be allowed to participate in that company's clinical trials. There will surely be increased scrutiny of COI related to major articles to assure full disclosure of conflicts.

There are additional implications for the relationship of patients to physicians. Some on social media have called for physicians to disclose relevant COIs to patients before initiating experimental or commercial treatments, and others have threatened to file lawsuits based on their doctor's undisclosed COIs. The potential liability of individual physicians and institutions for failure to disclose COIs is unknown, but one potential remedy could be inclusion of COI information in clinical trial informed consent documents.

With these considerations in mind, this Journal will re‐examine its instructions to authors, attempting to reduce the “ambiguity” of instructions. We will urge all authors to disclose relevant financial ties, including board memberships, consultancies and advisory activities, and equity ownership in companies with products that are the subject of the articles in question, or with products in the same general field of interest. We may also spot check COIs against the Open Payments database before publication. Importantly, we will advocate for a common standard of COI disclosure for all indexed journals. We will not advocate for extreme positions that would add to the regulatory burden already experienced by clinical trialists and their staff, or would create significant barriers to the vital advisory relationship between academic investigators and industry.

We invite readers to send letters to the editor on this matter and call attention to the comments of Oliver Sartor, a senior editor of this Journal, on the same subject [5].

Footnotes

Editor's Note: See the related editorial, “Conflicts of Interest, Baselga, and Clinical Trialists,” by Oliver Sartor, on page 1394 of this issue.

Contributor Information

Bruce A. Chabner, Email: bruce.chabner@theoncologist.com

Susan E. Bates, Email: seb2227@cumc.columbia.edu

Disclosures

Bruce A. Chabner: PharmaMar, EMD Serono, Cyteir (C/A, H), Biomarin, Seattle Genetics, PharmaMar, Loxo, Blueprint, Bluebird, Immunomedics (OI), Eli Lilly & Co., Genentech (ET). Susan E. Bates indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board.

References

- 1.Ornstein C, Thomas K. Top Cancer Researcher Fails to Disclose Corporate Financial Ties in Major Research Journals. The New York Times, Sept. 8, 2018. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/08/health/jose‐baselga‐cancer‐memorial‐sloan‐kettering.html?module=inline. Accessed September 8, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas K, Ornstein C. Top Sloan Kettering Cancer Doctor Resigns After Failing to Disclose Industry Ties. The New York Times, Sept. 13, 2018. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/13/health/jose‐baselga‐cancer‐memorial‐sloan‐kettering.html. Accessed September 14, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas K, Ornstein C. MSK Cancer Center Orders Staff to ‘Do a Better Job’ of Disclosing Industry Ties. The New York Times, Sept. 9, 2018. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/09/health/cancer‐memorial‐sloan‐kettering‐disclosure.html. Accessed September 9, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angell M. Transparency Hasn't Stopped Drug Companies from Corrupting Medical Research. The outrage over an influential doctor's hidden millions is misplaced. The New York Times, Sept. 14, 2018. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/14/opinion/jose‐baselga‐research‐disclosure‐bias.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article. Accessed September 14, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sartor O. Conflicts of Interest, Baselga, and clinical trialists. The Oncologist 2018. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]