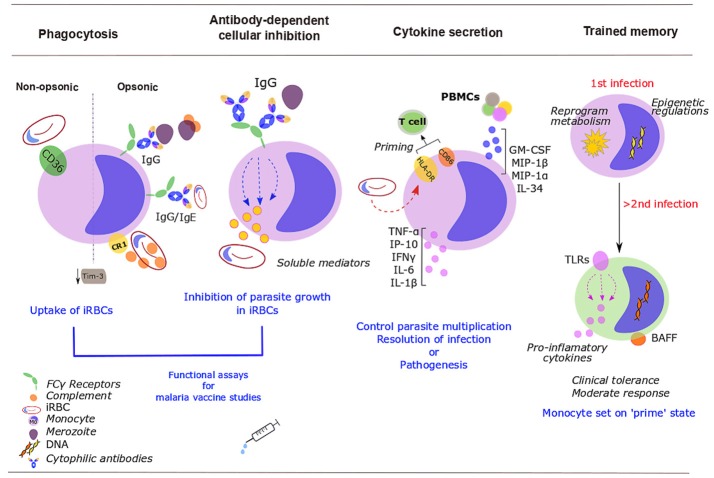

Figure 1.

Roles of monocytes during human malaria infection. Monocytes control parasite burden and contribute to host protection (or pathogenesis) through several mechanisms. Infected red blood cells (iRBCs) and merozoites are removed via opsonic or non-opsonic phagocytosis. Opsonic phagocytosis is mediated by either complement [binds to complement receptor 1 (CR1)] or malaria-specific antibodies (bind to Fcγ-receptors). Non-opsonic phagocytosis largely relies on CD36. Malaria down-regulates mucin-domain-containing molecule 3 (Tim-3). Soluble mediators released upon exposure to cytophilic antibodies stop Plasmodium from growing inside iRBCs [antibody-dependent cellular inhibition (ADCI)]. Monocyte phagocytosis and ADCI correlate with protection and might be used in vitro in malaria vaccine studies. Cytokine production balances protection/ susceptibility in the host. Plasmodium iRBCs increase HLA-DR; expression of activation markers, HLA-DR and CD86, might prime T cells response. PBMCs further activate and recruit monocytes through increased production of GM-CSF, MIP-1β, IL-34, TNF-α, or MIP-1α. Upon stimulation with P. falciparum iRBCs, monocytes secrete TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IP-10, and IFN- γ. After a challenge with Plasmodium, monocytes develop some sort of memory. Monocytes undergo epigenetic modifications, metabolic rewiring and altered cytokine secretion. These changes “prime” monocytes to a more moderate response to secondary encounters with the parasite. Some of these changes will persist over time, including the expression of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (involved in inflammatory cytokine production) and the membrane-bound form of the B-cell activating factor (BAFF).