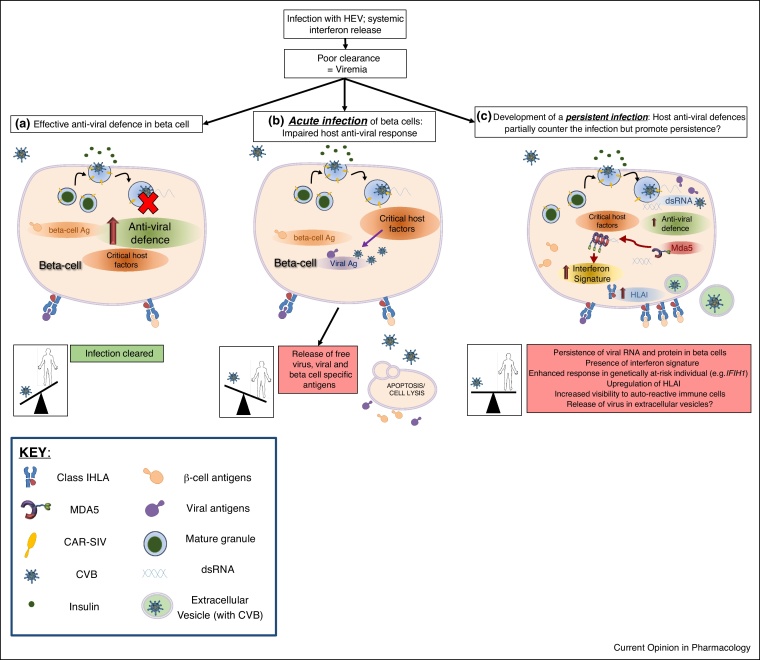

Figure 2.

A model of different beta cell responses to HEV infection. Following an infection with a HEV, systemic release of interferons primes the pancreas to respond to the likelihood of a local viral infection. (a) In most individuals this will lead to the induction of an anti-viral defence program which prevents the development of a sustained and productive infection of the beta cells. The virus is cleared and the host wins the battle. (b) In some individuals (possibly neonates?) who have an impaired anti-viral defence, enterovirus enters the cells and utilises critical host factors to establish a productive, lytic, infection. This can result in the release of free virus and/or viral and beta cell specific antigens. In individuals who are genetically predisposed to T1D, this damage may trigger the activation of islet autoreactive immune cells. (c) If the host anti-viral defence program only partially inhibits viral replication, then a persistent infection might develop. Persistent infections are associated with 5′UTR deletions of the viral genome and the formation of dsRNA. dsRNA can activate host pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Mda5 (encoded by IFIH1) and stimulate an enhanced interferon signature in cells. This will, in turn, lead to the upregulation of HLAI and enhanced presentation of beta cell and viral antigens at the cell surface. In `at-risk’ individuals this might then result in destruction by auto-reactive immune cells. Virus could be disseminated to other cells via extracellular vesicles, although this remains to be determined for human beta cells.