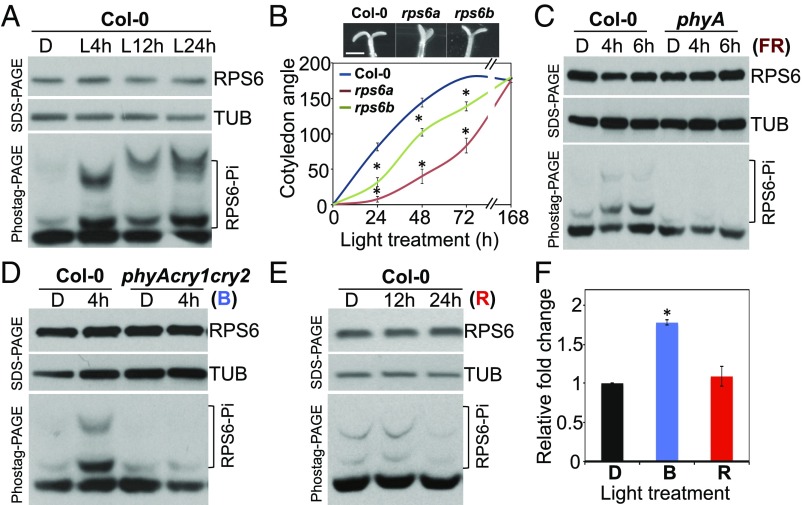

Fig. 2.

Phosphorylation and biological functions of RPS6. (A) Four-day-old etiolated Col-0 seedlings (dark, D) were treated with white light (L) for the indicated time. Total protein from each treatment was extracted and subjected to SDS/PAGE and Phostag-PAGE analyses. (B) Four-day-old etiolated Col-0, rps6a, and rps6b seedlings were treated with 15 μE white light to observe cotyledon opening for 7 d. Cotyledon opening angles are shown as mean ± SE *P < 0.001 vs. wild type, Col-0 (n = 16–22). Representative image showed cotyledons from etiolated seedlings treated with 72 h white light. (Scale bar: 1 mm.) (C) Four-day-old etiolated seedlings in the dark (D) of Col-0 and phyA were treated with 1.2 W/m2 FR light for 4 h or 6 h. (D) Four-day-old etiolated seedlings of Col-0 and phyA cry1 cry2 were treated with or without 35 μE blue (B) light for 4 h. (E) Four-day-old etiolated seedlings of Col-0 were treated with 35 μE (R) light for 12 h or 24 h. RPS6 and TUB were detected by RPS6- and α–tubulin-specific antiserum, respectively. The levels of TUB served as internal controls. (F) De novo protein synthesis was determined for 4-d-old etiolated seedlings of Col-0 in the dark (D) or treated with B or R light. Relative fold change was shown by normalizing to the level of newly synthesized proteins in etiolated wild-type seedlings. Values are mean ± SE (Student t test, *P < 0.01, n = 3).