Abstract

Background

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a of the major public health issues in Asia. The present study aimed to determine the prevalence of, and risk factors for GDM in Asia via a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, Ovid, Scopus and ScienceDirect for observational studies in Asia from inception to August 2017. We selected cross sectional studies reporting the prevalence and risk factors for GDM. A random effects model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of GDM and odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Eighty-four studies with STROBE score ≥ 14 were included in our analysis. The pooled prevalence of GDM in Asia was 11.5% (95% CI 10.9–12.1). There was considerable heterogeneity (I2 > 95%) in the prevalence of GDM in Asia, which is likely due to differences in diagnostic criteria, screening methods and study setting. Meta-analysis demonstrated that the risk factors of GDM include history of previous GDM (OR 8.42, 95% CI 5.35–13.23); macrosomia (OR 4.41, 95% CI 3.09–6.31); and congenital anomalies (OR 4.25, 95% CI 1.52–11.88). Other risk factors include a BMI ≥25 kg/m2 (OR 3.27, 95% CI 2.81–3.80); pregnancy-induced hypertension (OR 3.20, 95% CI 2.19–4.68); family history of diabetes (OR 2.77, 2.22–3.47); history of stillbirth (OR 2.39, 95% CI 1.68–3.40); polycystic ovary syndrome (OR 2.33, 95% CI1.72–3.17); history of abortion (OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.54–3.29); age ≥ 25 (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.96–2.41); multiparity ≥2 (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.24–1.52); and history of preterm delivery (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.21–3.07).

Conclusion

We found a high prevalence of GDM among the Asian population. Asian women with common risk factors especially among those with history of previous GDM, congenital anomalies or macrosomia should receive additional attention from physician as high-risk cases for GDM in pregnancy.

Trial registration

PROSPERO (2017: CRD42017070104).

Keywords: Prevalence, Risk factors, Gestational diabetes mellitus, Asia; meta-analysis

Background

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as any degree of dysglycaemia that occurs for the first time or is first detected during pregnancy [1, 2]. It has become a global public health burden [3]. GDM is one of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity for both the mother and the infant worldwide [4–13]. Mothers with GDM are at risk of developing gestational hypertension, preeclampsia and caesarean section [7, 14–16]. Apart from this, women with a history of GDM are also at significantly higher risk of developing subsequent type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular diseases [17, 18]. Babies born from GDM women are at risk of being macrosomic, may suffer from more congenital abnormalities and have a greater propensity of developing neonatal hypoglycaemia, and T2DM later in life [7, 19–24]. As such, it is important for healthcare policy makers to understand the burden of GDM for early detection and further intervention.

Up to now, there has been no gold standard criterion for the diagnosis. Different countries use different diagnostic criteria in determining its prevalence (Appendix 1). Based on these criteria, the estimated prevalence of GDM worldwide is 7.0% [25]. Prevalence varies from 5.4% in Europe [26] to 14.0% Africa [27]. In Asia, the prevalence of GDM ranges from 0.7 to 51.0% [28–30]. This vast disparity in prevalence rates may be due to differences in ethnicity [28, 30], diagnostic criteria [31–33], screening strategies [29, 34], and population characteristics [35, 36].

Diagnostic criteria have been developed by numerous associations such as: O′ Sullivan; American Diabetes Association (ADA); Australian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society (ADIPS); Carpenter-Coustan (CC); International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG); International Classification of Diseases (ICD); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG); Diabetes in Pregnancy Study group of India (DIPSI); Japan Diabetes Society (JDS); National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG); and World Health Organization (WHO); Canadian Diabetes Association (CDA); and so on. These diagnostic criteria vary in terms of screening methods and screening threshold.

Diagnosis of GDM primarily depends on the results of an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). The OGTT can be carried out via a 75-g two-hour test or a 100-g three-hour OGTT. The 75-g two-hour OGTT is a one-step approach, while the 100-g three-hour OGTT is usually implemented as the second step of a two-step approach. A diagnosis of GDM is made when one glucose value is elevated for the 75-g two-hour OGTT. Despite the presence of multiple diagnostic criteria to diagnose GDM, to date, there has been a degree of uncertainty around the optimum thresholds for a positive test [25, 37–59]. The thresholds for an elevated fasting glucose range from 92 mg/dl (5.1 mmol/L) to 140 mg/dl (7.8 mmol/L) [41, 44] while values for the two hours after OGTT range from 7.8 to 11.1 mmol/L [44, 46]. The IADPSG criteria is the most commonly used threshold for defining elevated values recently following the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study [60]. Overall, the 75-g two-hour test is more practical and convenient compared with the 100-g three-hour test. Furthermore, it appears to be more sensitive in predicting the pregnancy’s complication like gestational hypertension, preeclampsia and macrosomia than the 100-g three-hour test [61]. The reason for increased sensitivity is mainly that only one elevated glucose value is needed to diagnose GDM in 75-g two-hour test compared to 100-g three-hour test which requires two abnormal glucose values [60]. The thresholds used to define the abnormal values in the 100-g three-hour test have been based on the Carpenter and Coustan, NDDG and O’Sullivan criteria [49–51].

Moreover, the prevalence of GDM is expected to increase over years [62–64], especially in Asia. This is possibly due to increase in maternal age and obesity in Asia [65, 66]. A recent review reported the prevalence of GDM in Eastern and Southeast Asia is 10.1% (95% CI: 6.5–15.7%) [29]. There has been no review on the overall prevalence of GDM in Asia. Therefore, the aim of this meta-analysis is to estimate the prevalence of GDM in a broader scope including the countries across Asia. In addition, we also examine the odds ratio of risk factors for GDM among the Asian populations.

The recognition of risk factors of GDM for the Asian population is therefore important to identify women at risk, making an early diagnosis and instituting intensive lifestyle modification and metformin treatment to control blood glucose to reduce the likelihood of problems of GDM, before they become more severe. This may help prevent or ameliorate adverse complications.

We therefore conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the prevalence and factors associated with GDM in Asia.

Methods

The present review was registered with PROSPERO (2017: CRD42017070104) and conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [67].

Search strategy

Four databases were searched (PubMed, Ovid, Scopus and ScienceDirect) to do the literature search with the following search terms: (prevalence or incidence and/or risk factor) and (gestational diabetes or diabetes in pregnancy or gestational diabetes mellitus) and (Asia). A combination of expanded MeSH term and free-text searches were used as shown in Appendix 2. Then the reference lists of relevant articles were screened for its suitability to be recruited into this review.

Inclusion criteria

Any studies in Asia that reported prevalence and risk factors for GDM and fulfilled the following criteria were entered into the analysis, including the following factors: (1) conducted in Asian countries classified by the United Nations Statistics Division [68]; (2) reported prevalence and risk factors as primary results; (3) English peer review articles published in journals from inception to August 22, 2017; and (4) a sample size no less than 100 subjects. When several publications were actually derived from the same dataset or cohorts, we chose the data from the latest publication or largest cohort only. Similarly, when different screening criteria was used to diagnose GDM, we used the criteria with the highest prevalence for the risk factor calculation. We identified other pertinent studies through reverse-forward citation tracking and reference lists of related review articles.

Study selection

We imported those relevant articles identified through the databases into EndNote programme X5 version and we removed duplicate publications. Two reviewers independently performed the screening using the titles and abstracts to search for potentially eligible articles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned above. If there was a lack of information on the prevalence of GDM in the title and/or abstract, the full text was retrieved for further assessment. Discussions were held to resolve any disagreement for a final consensus before reviewing the full text each relevant article.

Quality assessment and data extraction

The checklist Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) was used to assess the quality of searched articles by two independent investigators [69]. The tool consists of 22 items that assess components in observation studies and whenever the information provided was not enough to assist in making judgement for a certain item, we agreed to grade that item with a ‘0’ meaning high risk of bias. Each article’s quality was graded as ‘good’ if STROBE score ≥14/22; or graded as ‘poor’ if STROBE score < 14/22 [69]. In this review, studies with STROBE score ≥ 14 were included in analysis. The scoring result was shown in Appendix 3.

One of the reviewers recorded the data from the selected studies into the extraction form using Excel, while the second reviewer verified the accuracy and completeness of the extracted data. The characteristics of the selected studies were extracted as follows: first author, year of publication, year of survey, country, setting, gestational age, screening procedure (one and/or two steps), diagnostic criteria for GDM, sample size, GDM cases, prevalence of GDM, odds ratio, relative risk of certain risk factors. Since we only collected published studies, the outcome measures extracted were gestational diabetes incidence and risk factors in terms of differences of proportion/percent of gestational diabetes in the total subjects examined. No ethics approval was needed in this review as the work consisted of secondary data collection and analysis only.

Data analysis

A random-effects (DerSimonian and Laird method) meta-analysis was used to pool the prevalence and odds ratio (OR) estimated from individual studies and reported with 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using the I2 index (low is < 25%, moderate 25–50%, and high > 50%), indicating the percent of total discrepancy due to studies variation [70]. Subgroup analyses for prevalence were performed by country, diagnostics criteria, screening methods and study setting. For Statistical analysis, StatDirect Statistical Software version 2.7.9 was employed.

The prevalence of GDM in Asia was analysed by subgrouping the country, and by the 10 different diagnostic criteria according to (1) IADPSG, (2) China Ministry of Health (China MOH), (3) ADA, (4) WHO, (5) DIPSI, (6) CC, (7) NDDG, (8) CC and WHO, (9) ICD 10th (ICD-10), (10) JDS. The data were also analysed by subgrouping the screening method and study setting.

The risk factors for GDM were reported in odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) by using a random effect.

Operational definitions

Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is a diagnostic test for gestational diabetes mellitus based on the glucose concentration in venous plasma using an accurate and precise enzymatic method [71]. Congenital anomaly in infants was defined as malformations involving the cardiovascular, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, and central nervous systems [72].

Results

Description of included studies

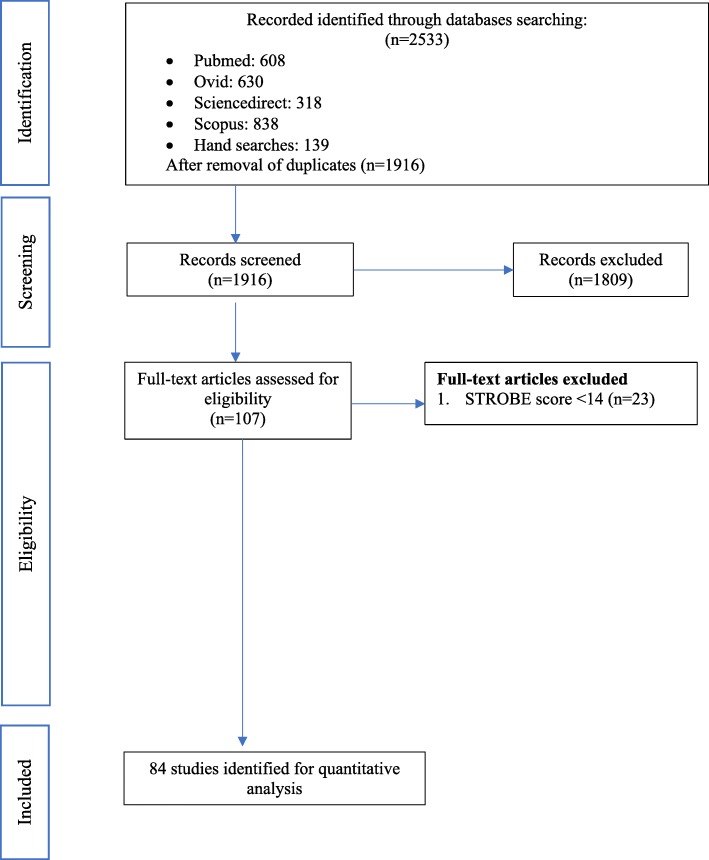

We identified 2533 manuscripts in the initial search as shown in Fig. 1. After removal of duplicate records (n = 617), 1916 studies were retrieved for further assessment. After careful evaluation of the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 107 studies fulfilled our criteria. Among 107 studies, 84 studies (1988–2017) were of STROBE score of ≥14. These studies were and these studies were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the literature screening process

Characteristics of included studies

The main characteristics of the included studies are shown in the Appendix 4. A total sample of 2, 314,763 pregnant women from 20 countries were included in the analysis. Twenty-four were in India [73–96], nine in Iran [97–105], 8 in China [106–113], 7 in Saudi Arabia [28, 114–119], four in Thailand [120–123], Sri Lanka [124–127] and Japan [128–131], three in South Korea [132–134], Bangladesh [135–137] and Israel [138–140]. Additionally, two were in Vietnam [141, 142], Malaysia [143, 144], Qatar [145, 146], Pakistan [147, 148] and Nepal [149, 150]. One each were from Yemen [151], Hong Kong [152], Singapore [153], Taiwan [154] and Turkmenistan [155].

In terms of diagnostic criteria, a total of 23 studies used the WHO criteria, 13 used IADPSG, 13 used ADA, 13 used CC, 12 used DIPSI, 4 used NDDG, 3 used JDS, 1 used ICD-10, 1 used China MOH criteria and 1 used the combination of the CC and WHO criteria (Table 1). Out of 84 studies, the most commonly used one-step screening procedure was applied in 53 studies (Table 1). A One step screening procedure is defined as the pregnant women undergoing a 75 g OGTT. Two-step screening procedure was used in 30 studies. Two-step screening procedure is defined as pregnant women firstly undergoing a 50 g one-hour Glucose Challenge Test (GCT). If the woman tested positive in the 50 g GCT, they were then required to undergo either a 75 g or 100 g OGTT.

Table 1.

Pooled prevalence and 95% confidence interval of gestational diabetes by subgroup analysis

| Variable | N | Total sample size | Total GDM | Prevalence, % | 95% CI | P-value | I2, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | |||||||

| Taiwan | 1 | 132 | 51 | 38.6 | 30.3–46.9 | NA | NA |

| Hong Kong | 1 | 520 | 169 | 32.5 | 28.5–36.5 | NA | NA |

| Saudi Arabia | 7 | 13,865 | 3192 | 22.9 | 12.9–32.9 | 99.51 | < 0.0001 |

| Vietnam | 2 | 5474 | 1224 | 22.3 | 18.4–26.2 | 91.94 | < 0.0001 |

| Malaysia | 2 | 2136 | 359 | 18.5 | 6.2–30.8 | 97.97 | < 0.0001 |

| Singapore | 1 | 909 | 160 | 17.6 | 15.1–20.1 | NA | NA |

| Thailand | 4 | 24,168 | 1872 | 17.1 | 6.3–27.8 | 99.11 | < 0.0001 |

| Iran | 9 | 9872 | 1146 | 14.9 | 10.2–19.6 | 98.58 | < 0.0001 |

| Qatar | 2 | 2205 | 323 | 13.3 | 7.4–19.3 | 93.54 | < 0.0001 |

| China | 8 | 156,942 | 11,394 | 12.6 | 8.6–16.7 | 99.78 | < 0.0001 |

| Sri lanka | 4 | 3577 | 380 | 11.4 | 5.1–17.8 | 97.93 | < 0.0001 |

| South Korea | 3 | 1,316,307 | 98,845 | 10.5 | 5.8–15.3 | 99.87 | < 0.0001 |

| India | 24 | 17,049 | 1679 | 8.8 | 6.7–10.9 | 96.57 | < 0.0001 |

| Bangladesh | 3 | 2785 | 226 | 8.2 | 6 l.0–10.5 | 71.61 | 0.03 |

| Pakistan | 2 | 1642 | 127 | 7.7 | 6.4–9.0 | 0 | 0.752 |

| Turkmenistan | 1 | 1620 | 109 | 6.7 | 5.5–7.9 | NA | NA |

| Israel | 3 | 737,978 | 36,822 | 5.3 | 3.7–7.0 | 99.89 | < 0.0001 |

| Yemen | 1 | 311 | 16 | 5.1 | 2.7–6.6 | NA | NA |

| Japan | 4 | 15,109 | 390 | 2.8 | 1.9–3.7 | 84.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Nepal | 2 | 2162 | 26 | 1.5 | 0.2–3.2 | 84.13 | 0.012 |

| Subtotal | 84 | 2,314,763 | 158,510 | 11.5 | 10.9–12.1 | 99.57 | < 0.0001 |

| Diagnostic criteria | |||||||

| IADPSG | 13 | 42,317 | 5148 | 20.9 | 17.3–24.6 | 99.17 | < 0.0001 |

| CHINA MOH | 1 | 14,986 | 2987 | 19.9 | 19.3–20.6 | NA | NA |

| ADA | 13 | 379,583 | 15,501 | 13.9 | 11.5–16.2 | 98.68 | < 0.0001 |

| WHO | 23 | 134,152 | 9750 | 13 | 9.6–16.4 | 99.38 | < 0.0001 |

| DIPSI | 12 | 9879 | 1114 | 8.3 | 5.7–10.9 | 94.76 | < 0.0001 |

| CC | 13 | 384,146 | 23,714 | 7.6 | 6.6–8.7 | 99 | < 0.0001 |

| NDDG | 4 | 31,734 | 1577 | 4.3 | 1.4–7.3 | 99.2 | < 0.0001 |

| CC&WHO | 1 | 2000 | 75 | 3.7 | 2.9–4.6 | NA | NA |

| ICD-10 | 1 | 1,306,281 | 98,403 | 3.7 | 1.2–6.2 | NA | NA |

| JDS | 3 | 9685 | 241 | 3.6 | 1.2–6.0 | 88.33 | < 0.0001 |

| Subtotal | 84 | 2,314,763 | 158,510 | 11.5 | 10.9–12.1 | 99.59 | < 0.0001 |

| Setting | |||||||

| Hospital | 71 | 423,878 | 31,598 | 12.1 | 11–13.1 | 99.34 | < 0.0001 |

| Community | 13 | 1,890,885 | 126,912 | 11.1 | 9.8–12.5 | 99.87 | < 0.0001 |

| Subgroup | 84 | 2,314,763 | 158,510 | 11.5 | 10.9–12.1 | 99.59 | < 0.0001 |

| Screening Methods | |||||||

| One-step | 53 | 631,808 | 38,515 | 14.7 | 13.5–15.9 | 99.5 | < 0.0001 |

| Not stated | 1 | 1,306,281 | 98,403 | 7.5 | 7.5–7.6 | NA | NA |

| Two-steps | 30 | 376,674 | 21,592 | 7.2 | 6.4–8.0 | 98.82 | < 0.0001 |

| Subtotal | 84 | 2,314,763 | 158,510 | 11.5 | 10.9–12.1 | 99.57 | < 0.0001 |

The setting of the study was examined in subgroup analysis; 71 studies were hospital-based and 13 studies were community based.

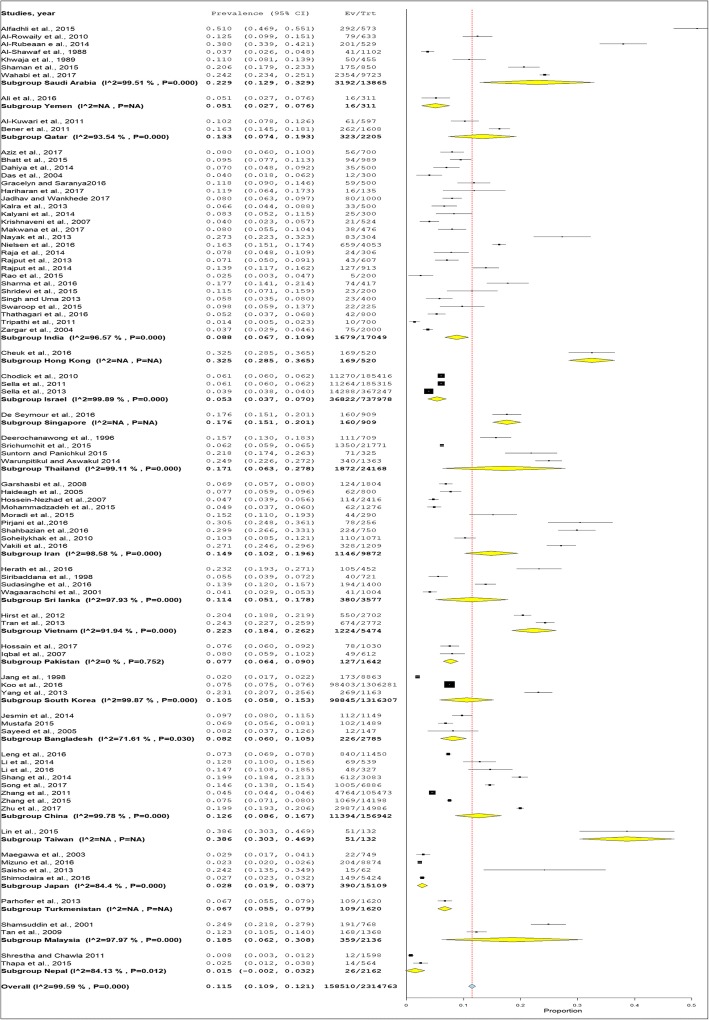

Prevalence of GDM

The overall mean prevalence of GDM was 11.5% (95% CI 10.9–12.1) (Fig. 2). Table 1 shows the prevalence of GDM across difference covariates such as by country, diagnostics criteria, screening step and study setting. The prevalence of GDM by country was highest in Taiwan (38.6%), followed by Hong Kong (32.5%) and Saudi Arabia (22.9%). The lowest prevalence of GDM was in Nepal (1.5%) followed by Japan (2.8%). The prevalence of GDM by diagnostic criteria was highest with IADPSG (20.9%) followed by China MOH (19.9%). The prevalence of GDM was much lower when the studies used the common and popular criteria of WHO 1980–2013 or ADA 2002–2014 (13.0 to 13.9%) versus the IADPSG and China MOH which gave a prevalence of 19.9 and 20.9%, respectively. The prevalence of GDM by screening methods was very different, where the one-step screening methods reported a prevalence of GDM of 14.7%, while the prevalence of GDM two-step screening method (7.2%) was half that of the one-step method. The prevalence of GDM was almost similar between hospital and community setting (12.1% versus 11.1%).

Fig. 2.

The forest plot of the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Asia

Risk factors of GDM

The risk factors of GDM was analysed in this current review. The most important risk factors in GDM among Asian population were rated based on pooled analysis of the included studies (Table 2). This meta-analysis found that the odds of GDM was increased by history of previous GDM (OR 8.42, 95% CI: 5.35–13.23), congenital anomalies (OR 4.25, 95% CI 1.52–11.88), and macrosomia (OR 4.41, 95% CI 3.09–6.31). Other risk factor included BMI ≥25 (OR 3.27, 95% CI 2.81–3.80) and pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) (OR 3.20, 95% CI 2.19–4.68).

Table 2.

Pooled prevalence and 95% confidence interval of gestational diabetes according to the risk factors

| Variable | N | Exposure in GDM | Total GDM | Exposure in Non-GDM | Total Non-GDM | OR | 95% CI | I2, % | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of previous GDM | 24 | 343 | 3246 | 272 | 20,646 | 8.42 | 5.35–13.23 | 80.92 | < 0.001 |

| History of congenital anomalies | 6 | 32 | 655 | 50 | 3262 | 4.25 | 1.52–11.88 | 64.64 | 0.015 |

| History of macrosomia | 29 | 397 | 4275 | 1001 | 29,506 | 4.41 | 3.09–6.31 | 81.14 | < 0.001 |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 33 | 13,304 | 42,306 | 80,126 | 582,707 | 3.27 | 2.81–3.80 | 93.49 | < 0.001 |

| PIH | 12 | 163 | 1891 | 612 | 18,468 | 3.2 | 2.19–4.68 | 68.96 | < 0.001 |

| Family History of Diabetes | 60 | 3177 | 11,068 | 12,336 | 94,962 | 2.77 | 2.22–3.47 | 93.76 | < 0.001 |

| History of stillbirth | 25 | 261 | 2786 | 1158 | 21,257 | 2.39 | 1.68–3.40 | 75.38 | < 0.001 |

| PCOS | 7 | 2424 | 113,827 | 26,777 | 1,566,026 | 2.33 | 1.72–3.17 | 94.07 | < 0.001 |

| History of abortion | 19 | 803 | 2658 | 2404 | 16,844 | 2.25 | 1.54–3.29 | 91.37 | < 0.001 |

| Age ≥ 25 | 34 | 226,788 | 354,080 | 2,637,545 | 4,798,678 | 2.17 | 1.96–2.41 | 96.91 | < 0.001 |

| Multiparity ≥2 | 32 | 21,069 | 31,901 | 290,125 | 434,198 | 1.37 | 1.34–1.52 | 86.55 | < 0.001 |

| History of preterm delivery | 9 | 230 | 2274 | 837 | 12,748 | 1.93 | 1.21–3.07 | 76.09 | < 0.001 |

| History of neonatal death | 5 | 26 | 550 | 58 | 1593 | 1.8 | 0.86–3.79 | 43.29 | 0.133 |

| Illiteracy | 7 | 118 | 2919 | 604 | 10,372 | 1.29 | 0.82–2.04 | 65.63 | 0.008 |

| Current smoking | 8 | 1257 | 14,162 | 18,924 | 213,495 | 1.04 | 0.98–1.11 | 0 | 0.93 |

| Current drinking | 5 | 30 | 2422 | 916 | 38,433 | 0.79 | 0.54–1.14 | 0 | 0.66 |

| Primigravida | 18 | 7363 | 8753 | 38,871 | 47,228 | 0.55 | 0.41–0.73 | 85.99 | < 0.001 |

Risk factors such as family history of diabetes (OR 2.77, 2.22–3.47), history of stillbirth (OR 2.39, 95% CI 1.68–3.40), Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (OR 2.33, 95% CI1.72–3.17), history of abortion (OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.54–3.29), age ≥ 25 (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.96–2.41), multiparity ≥2 (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.24–1.52), and a history of preterm delivery (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.21–3.07) in relation to GDM, ranging from 1.93–2.77 (p value < 0.05). On the other hand, for risk factors such as history of neonatal death, illiteracy and current smoking, the odds for GDM ranged from 1.04 to 1.80 (p value > 0.05). Primigravida status and current drinking was found to be protective factors for GDM with an OR of 0.55 and 0.79 (p value < 0.05), respectively.

Discussion

The present meta-analysis included 84 studies from 20 countries across Asia. We compiled the prevalence and risk factors data from a huge population size (n = 2,314,763). The pooled prevalence of GDM was 11.5% (95% CI 10.9–12.1). This figure is considered more representative of the burden of GDM across Asian populations.

This prevalence of GDM in Asia is found to be higher than European countries (5.4%) but lower than in African countries (14.0%) [27, 51]. We have no clear reason for such a discrepancy, but we speculate that it may due to maternal age and BMI disparities, as well as ethnic background [156]. For example, South Asian have greater odds of developing GDM than White European and Black Africa at same age [157]. Similarly, South Asian women were older and more obese among GDM patients [157]. Therefore, advancing age, increasing BMI and racial group are associated to the high prevalence of GDM in Asia. It could also be due to a genetic predisposition of Asians to have a higher risk of insulin resistance compared to Caucasian [158]. The higher prevalence of GDM in Asia and Africa is higher than that of Europe. This is consistent with the higher prevalence of T2DM and GDM seen in Asia compared to Europe [62].

Prevalence of GDM including India and Middle Eastern countries makes a total of 20 countries. Our findings on prevalence of GDM are fairly similar to a recent study that reported the prevalence of GDM in 8 Eastern and Southeast Asian countries 10.1% (95% CI 6.5–15.7) [29].

The high heterogeneity in the overall prevalence seen in our study may be due to several reasons, such as different diagnostic criteria and screening methods used by different countries. For example, while several studies used the ADA criteria to screen for GDM, they also used different cut-off value of 92 mg/dl (5.1 mmol/l values as well) or 95 mg/dl (5.2 mmol/l) for the 75 g OGTT. Furthermore, even though within the same country, different diagnostic criteria were used to diagnose GDM. For example, seven diagnostic criteria were used in India and three in Vietnam, giving a broad range of prevalence of GDM ranging from 6.7–10.9 and 18.4.4–26.2, respectively. Hence it is not surprising that high heterogeneity of prevalence of GDM within a country is seen. Similarly, the sample size was important when determining prevalence of GDM, as the literature reports that there is a positive correlation between sample size and the prevalence [159]. In our meta-analysis, there were 5 studies [109, 133, 138–140] with a large sample size which gives larger weight to the prevalence of GDM. This may contributed to the heterogeneity in the results.

The IADPSG and China MOH diagnostic criteria usually results in higher prevalence of GDM where the prevalence can be higher by 3.5 to 45.3% [160]. This is partly because a lower cut-off value for fasting glucose is used [161]. These two diagnostic criteria are less popular in the screening for GDM. China MOH was another diagnostic criterion with higher prevalence of GDM. This criterion acknowledged hyperglycaemia in pregnancy be tested at an early stage of pregnancy and later divided them into T2DM in pregnancy and GDM [156] . Hence, this significantly increased the detection and prevalence rate.

The ADA and WHO criteria are the most popular diagnostic screening criteria used. The prevalence of GDM based on these criteria are lower than other criteria. There are also many different versions of these criteria over the years, with different cut-off glucose values to classify GDM. For instance, the WHO 2013 has a higher cut-off value for the 2-h plasma glucose compared to WHO 1999, and other diagnostic criteria. Different countries and studies used different diagnostic criteria and it has an impact on the prevalence of GDM. Using a lower threshold value in GDM screening would result in more cases compared to those using higher threshold values.

This review demonstrated differences in prevalence of GDM by subgroup screening methods in terms of other than diagnostic criteria that need to be examined when trying to explain the inconsistency in the prevalence of GDM between studies. In the analysis, the prevalence of GDM using one-step screening was nearly double that using the two-steps screening (14.7 and 7.2%. respectively).

This is an unexpected finding because a bigger dose of glucose of 75-g will be used in one-step screening method. In comparison with two step method, a 50-g oral glucose will be used in the first round so it will detect fewer GDM cases as only those who are positive on 50-g proceed to the next step using 75 or 100-g. Hence, the overall prevalence of GDM based on one-step screening method will be higher. This is consistent with the literature where the two-step screening method is less sensitive than the one-step screening method in diagnosing GDM, and the two-step screening method will miss approximately 25% of cases [162]. In view of one-step screening method is more practical, cost effective and more convenient [161, 163]. Hence, it is a more advantage to use one-step method instead of two-steps method in diagnosing GDM. Having say so till now there is no consensus for use of the one-step versus two-step screening method among national and international organizations. Recent Cochrane review in 2017 reported that there is insufficient evidence to suggest which strategy is best for diagnosing GDM [164].

The majority of the included studies in this review were conducted in hospitals (12.0%). 71 studies had conducted the screening for GDM during antenatal visits at the hospitals. Meanwhile, 13 studies were conducted in the community hospitals, which mostly involved the authorities in healthcare such as the MOH to perform wide coverage screening for GDM at national, state or regional level.

Taiwan had the highest prevalence of GDM (38.6%). The study conducted in Taiwan had a small sample size (n = 132) and the pregnant women were older (mean age of 32) and the chosen study location was mainly inhabited by aboriginal tribes. On top of that the data were collected using 2 different diagnostic criteria. The 100 g three-hour OGTT test was used before 2012 and 75 g OGTT test with a better sensitivity was used since 2012. As we know the prevalence of GDM may be varied according to different diagnostic criteria used [165]. Hong Kong also had a high prevalence of GDM (32.5%) due to the screening was performed at referral hospital for GDM cases, and these GDM group are those in advance age as the mean age of the study population was 34 and higher parity. The prevalence of GDM in Taiwan and Hong Kong were derived from only one study each and hence the reported prevalence are not representable for the true burden of GDM in their countries.

The risk factors of GDM was analysed in this current review. Those with multiparity ≥2, previous history of GDM, congenital anomalies, stillbirth, abortion, preterm delivery, macrosomia, having concurrent PIH, PCOS, age ≥ 25, BMI ≥25, and family history of diabetes are the significant risk factors predictive of GDM in current pregnancy (OR values ranged from 1.90 to 8.42). Most of the guidelines, including those of ADA in 2016, recommend universal screening for GDM in second trimester [166]. Other organizations, such as NICE in 2015, recommend screening for GDM using risk factors at the booking appointment. The risk factors considered by NICE in 2015 are BMI ≥ 30, a history of macrosomia of 4.5 kg or more, previous gestational diabetes, a family history of diabetes, or belonging to an ethnic minority with a high prevalence of gestational diabetes such as South Asian and Middle Eastern [167]. In Malaysia, pregnant women age ≥ 25 together with risk factors should be screened for GDM at booking. The risk factors for GDM are those with BMI ≥ 27, previous history of GDM, macrosomia (birth weight > 4 kg), bad obstetric history, glycosuria ≥2 + on two occasions, first degree relative with diabetes mellitus, concomitant obstetrics problems such as hypertension or pregnancy-induced hypertension, polyhydramnios and current use of corticosteroids [168]. While in France, the identified risk factors requiring the search for GDM are maternal age ≥ 35 years, BMI ≥ 25, history of diabetes in first-degree relatives, personal history of GDM or GDM [169].

Our study showed that those with history of previous GDM have 3.5 times odds more likely to develop GDM compare those without history of previous GDM. This finding is consistent with previous study [28, 114].

History of congenital anomalies have 4.3 times odds more likely to develop GDM compare those without history of congenital anomalies. This finding is consistent with previous study [28, 93]. Similarly, to those with history of macrosomia and PIH have 4 times and 3 times for odds to have higher insulin resistance. This is consistent with the previous finding [84, 91].

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a common cause of insulin resistance [104, 151]. Women with PCOS have higher risk of developing GDM [104, 151] and this is consistent with our study (OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.72–3.17).

BMI is commonly used in risk-based screening for GDM. Prevalence of GDM is also increased with increasing pre-pregnancy BMI [170]. For instance, prevalence of GDM was highest among Asian women with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (13.78%), followed by BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (10.22%) and BMI ≥ 20 kg/m2 (6.09%). In this current review, we used a BMI cut-off of ≥25 kg/m2 and found the odds ratio for GDM is 3.39 (95% CI2.92–3.93). Our result is consistent with previous studies where the odds of BMI ≥25 kg/m2 for GDM ranged from 2.78 (95% CI: 2.60–2.96) to 3.56 (95% CI: 3.05–4.21) [65, 171].

A BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 has a lower sensitivity (24.9%) but a good specificity (88.7%) in comparison to using a cut-off level of BMI ≥ 21 kg/m2 which has a higher sensitivity of 68.4% but a lower specificity of 53.6% [170]. Literature suggests a BMI ≥25 kg/m2 is more suitable to be used among African-American women as the sensitivity (46.2%) and specificity (81.5%) are higher. A BMI ≥21.0 kg/m2 would be recommended as cut off threshold to screen GDM with a better sensitivity however BMI I ≥ 25.0 kg/m2 was the most commonly used threshold among the included studies [170].

Obesity is one of the main factors in the development of diabetes and GDM [64, 172]. BMI is a commonly used method to measure the severity of obesity [173]. However, the cut-off point used to diagnose obesity is different between western and Asian countries [170]. For example, prevalence of GDM was highest among Asian women with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (13.78%), followed by BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (10.22%) and BMI ≥ 20 kg/m2 (6.09%). In this current review, we have employed a BMI cut-off of ≥25 kg/m2 and found the odds ratio for GDM is 3.27 (95% CI2.81–3.80). Our results are consistent with previous studies in which the odds of BMI ≥25 kg/m2 for GDM ranged from 2.78 (95% CI: 2.60–2.96) to 3.56 (95% CI: 3.05–4.21) [65, 171].

Maternal age is an established risk factor for GDM, but there is no consensus on age’s relation to increased risk of GDM [174]. ADA recommended the lowest cutoff of ≥25 years to screen for GDM as early as possible [43]. This is supported by our results showing that the odds of GDM by age ≥ 25 is OR 2.17 (95% CI 1.96–2.41), and consistent with previous study findings showing that screening for GDM among patients aged 25 years and above with other risk factors indeed has a higher predictive value in identifying GDM [175].

According to previous studies, family history of diabetes (particularly in a first-degree relative) increases the risk for GDM [64, 66]. Onset of GDM has a familial tendency and this potentially suggests that there is a genetically predisposition to develop GDM [176–178]. In current review, family history of diabetes has OR 2.77(95% CI 2.22–3.47) of GDM. Our results are consistent with a previous study in which the odds of family history of diabetes for GDM among Iranian women was determined to be OR 3.46 (95%CI 2.8–4.27) [179].

The strength of this review paper is that it not only included more countries, including India and countries in Middle East which were both not included in previous reports. Furthermore, the articles with poor quality in STROBE were excluded to maintain the reliability of findings of current review.

Our meta-analysis has the following limitations. Firstly, we are aware that the studies included in this meta-analysis are not a true reflection of the Asian population. Although there were 24 studies in the meta-analysis come from India, they only contributed 17,049 patients out of the general population of 1.3 billion in India. Similarly, the 8 Chinese studies only contributed 156,942 patients out of 1.4 billion in China. Based on the inclusion criteria, we have recruited the above 32 studies in this review. Thus, we must interpret the results of this meta-analysis cautiously within the context of their limitations. Secondly, there was a high heterogeneity in our result. This could be due to different diagnostic criteria and screening methods used by different countries. This high heterogeneity may also be due to the different population characteristics as 20 countries were included in this meta-analysis. Thirdly, this meta-analysis included manuscripts from the inception to 2018, covering a vast range of clinical and diagnostic criteria and practice changes. The threshold value of two-hour in one-step 75-g method and three-hour in 100-g two-steps methods are reduced over time, increasing the identification rates of GDM cases over time. Therefore, changes of threshold value to identify GDM could inevitably cause high heterogeneity to the results. Finally, studies with small sample size were also included in this meta-analysis. Hence the result of this meta-analysis may suffer from high variability. Therefore, some estimates of the meta-analysis could be influenced by heterogeneity between the studies.

Conclusions

Our current study provides an estimation of the prevalence and risk factors of GDM in Asia. Our study shows that the pooled estimation of prevalence was 11.5%. We have identified the following risk factors of developing GDM: multiparity≥2; previous history of GDM; congenital anomalies; stillbirth; abortion; preterm delivery; macrosomia; concurrent PIH; PCOS; age ≥ 25; BMI ≥25; and family history of diabetes.

It is important that the risk factors for GDM are recognized in order the clinicians are able to identify those at risk of getting GDM for early diagnosis and further intervention. We recommend that clinicians screen for GDM as early as possible among those with risk factors using one-step screening method instead of two-step screening method. If the results are negative, the test should be repeated in between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kuan Meng Soo for assistance in data sorting and librarian Nur Farhana Abdullah who assisted in searching and providing articles in full texts.

Funding

This work was supported by the Universiti Putra Malaysia (grant numbers: UPM/700–2/1/GP-IPS/2018/9593800), High Impact Grant (UPM/800–3/3/1/GPB/2018/9659600) and Graduate Research Fellowship (UPM/SPS/GS48750). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ADA

American diabetes association

- ADIPS

Australian diabetes in pregnancy society

- CC

Carpenter-coustan

- CDA

Canadian diabetes association

- China MOH

China ministry of health

- CI

Confidence interval

- DIPSI

Diabetes in pregnancy study group of India

- EASD

European association for the study of diabetes

- GCT

Glucose challenge test

- GDM

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- IADPSG

International association of the diabetes and pregnancy study groups

- ICD

International classification of diseases

- JDS

Japan diabetes society

- NDDG

National diabetes data group

- OGTT

Oral glucose tolerance test

- OR

Odds ratio

- PCOS

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

- PIH

Pregnancy induced hypertension

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- WHO

World Health Organization

Appendix 1

Table 3.

Screening criteria for the diagnosis of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

| Diagnostics criteria | Steps | OGTT | No. abnormal | Fasting mg/dl (mmol/l) | 1 H mg/dl (mmol/l) | 2 H mg/dl (mmol/l) | 3H mg/dl (mmol/l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O′ Sullivan 1964 [49] | 2 | 100 g | ≥ 2 | 90 (5) | 165 (9.2) | 145 (8.1) | 125 (6.9) |

| NDDG 1979 [50] | 2 | 100 g | ≥ 2 | 105 (5.8) | 190 (10.6) | 165 (9.2) | 145 (8.0) |

| CC 1982 [51] | 2 | 100 g | ≥ 2 | 95 (5.3) | 180 (10) | 155 (8.6) | 140 (7.8) |

| EASD 2012 [52] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | 108 (6) | – | 162 (9) | – |

| ACOG [53] | 2 | 100 g | ≥ 2 | 95 (5.30 | 180 (10) | 155 (8.6) | 140 (7.8) |

| ADIPS 1998 [54] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | 100 (5.5) | – | 144 (8.0) | – |

| IADPSG 2010 [55] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 2 | 92 (5.1) | 180 (10) | 153 (8.5) | – |

| DIPSI [25] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | – | – | 140 (7.8) | – |

| JDS [56] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 2 | 126 (7) | – | 200 (11.1) | – |

| China MOH [57] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | 92 (5.1) | 180 (10) | 153 (8.5) | – |

| ICD-10 O24.4 (58) | 2 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | 92 (5.1) | 180 (10) | 153 (8.5) | – |

| ADA 1997 [59] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | 126 (7) | – | 200 (11.1) | – |

| ADA 2002 [37] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | 126 (7) | – | 200 (11.1) | |

| ADA 2003 [38] | 2 | 100 g | ≥ 2 | 95 (5.3) | 180 (10) | 155 (8.6) | 140 (7.8) |

| ADA 2004 [39] | 2 | 100 g | ≥ 1 | 95 (5.3) | 180 (10) | 155 (8.6) | 140 (7.8) |

| ADA 2011 [40] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | 92 (5.1) | – | – | – |

| ADA 2012 [41] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | 92 (5.1) | 180 (10) | 153 (8.5) | – |

| ADA 2014 [42] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | – | 180 (10) | 153 (8.5) | – |

| WHO 1980 [43] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | 140 (7.8) | – | 200 (11.1) | – |

| WHO 1998 [44] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | 126 (7) | – | 200 (10) | – |

| WHO 1985 [45] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | – | – | 140 (7.8) | – |

| WHO 1999 [44] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | 126 (7) | – | 140 (7.8) | – |

| WHO 2006 [46] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | 126 (7) | 180 (10) | 200 (11.1) | – |

| WHO 2013 [47] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 1 | 92 (5.1) | 180 (10) | 153 (8.5) | – |

| CDA 2008 [48] | 1 | 75 g | ≥ 2 | 95 (5.3) | 190 (10.6) | 160 (8.9) | – |

ACOG The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, ADA American Diabetes Association, ADIPS Australian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society, CC Carpenter-Coustan, CDA Canadian Diabetes Association, DIPSI Diabetes in Pregnancy Study group of India, EASD European Association for the Study of Diabetes, IADPSG International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups, ICD International Classification of Diseases, JDS Japan Diabetes Society, NDDG National Diabetes Data Group, OGTT Oral Glucose tolerance Test, WHO World Health Organization, MOH Ministry of Health

Appendix 2

Table 4.

Search terms used for final search 22 August 2017

| Searches | Search terms | Pubmed | Ovid | Sciencedirect | Scopus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # 1 | Incidence | 2,424,449 | 230,603 | 194,404 | 2,761,766 |

| # 2 | Prevalence | 2,583,495 | 253,174 | 141,405 | 2,490,683 |

| # 3 | Risk factor | 1,264,673 | 726,298 | 209,966 | 4,281,945 |

| # 4 | Diabetes in pregnancy | 36,326 | 10,331 | 4542 | 135,425 |

| # 5 | Gestational diabetes mellitus | 18,375 | 8665 | 2156 | 46,028 |

| # 6 | Asia | 755,317 | 26,037 | 52,858 | 1,413,577 |

| # 7 | #1 OR #2 | 2,812,427 | 461,976 | 322,237 | 4,476,331 |

| # 8 | #4 OR #5 | 36,326 | 18,121 | 5314 | 145,571 |

| #9 | #7 AND #8 AND #3 AND #6 | 608 | 630 | 318 | 838 |

Appendix 3

Table 5.

Assessment of risk of bias of included studies by STROBE Checklist

| 1a | 1b | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6a | 6b | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12a | 12b | 12c | 12d | 12e | 13a | 13b | 13c | 14a | 14b | 14c | 15 | 16a | 16b | 16c | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfadhli et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ali et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Al-Kuwari et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Al-Rowaily et al., 2010 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Al-Rubeaan e al., 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Al-Shawaf et al., 1988 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Aziz et al., 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Bener et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Bhatt et al., 2015 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cheuk et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Chodick et al., 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Dahiya et al., 2014 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Das et al., 2004 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| De Seymour et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Deerochanawong et al., 1996 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Garshasbi et al., 2008 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Gracelyn and Saranya2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Haideagh et al., 2005 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Hariharan et al., 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Herath et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Hirst et al., 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hossain et al., 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Hossein-Nezhad et al.,2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Iqbal et al., 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Jadhav and Wankhede 2017 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Jang et al., 1998 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Jesmin et al., 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Kalra et al., 2013 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Kalyani et al., 2014 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Khwaja et al., 1989 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Koo et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Krishnaveni et al., 2007 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Leng et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Li et al., 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Li et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Lin et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Maegawa et al., 2003 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Makwana et al., 2017 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Mizuno et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Mohammadzadeh et al., 2015 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Moradi et al., 2015 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mustafa 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Nayak et al., 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Nielsen et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Parhofer et al., 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Pirjani et al.,2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Raja et al., 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Rajput et al., 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Rajput et al., 2014 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Rao et al., 2015 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Saisho et al., 2013 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Sayeed et al., 2005 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sella et al., 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Sella et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Shahbazian et al.,2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Shaman et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Shamsuddin et al., 2001 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Shang et al., 2014 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sharma et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Shimodaira et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Shrestha and Chawla 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Shridevi et al., 2015 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Singh and Uma 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Siribaddana et al., 1998 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Soheilykhak et al., 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Song et al., 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Srichumchit et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sudasinghe et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Suntorn and Panichkul 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Swaroop et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tan et al., 2009 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Thapa et al., 2015 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Thathagari et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tran et al., 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tripathi et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Vakili et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Wagaarachchi et al., 2001 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Wahabi et al., 2017 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Warunpitikul and Aswakul 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yang et al., 2013 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Zargar et al., 2004 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Zhang et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Zhang et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Zhu et al., 2017 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

1(Presence of item)

0(Absence of item)

†Quality is defined by a STROBE score ≥ 14/22 (good) and < 14/22 (poor)

Appendix 4

Table 6.

Characteristics of Included studies

| Author, year | Country | Association | Diagnostic criteria | Study Setting | Screening Methods | Screening dosage | GDM + | Sample size | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfadhli et al., 2015 | Saudi Arabia | IADPSG | IADPSG | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 292 | 573 | 51.0 |

| Ali et al., 2016 | Yemen | ADA | ADA 2002 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 16 | 311 | 5.1 |

| Al-Kuwari et al., 2011 | Qatar | ADA | ADA 2004 | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 75 g | 61 | 597 | 10.2 |

| Al-Rowaily et al., 2010 | Saudi Arabia | WHO | WHO 1999 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 79 | 633 | 12.5 |

| Al-Rubeaan e al., 2014 | Saudi Arabia | ADA | ADA 2011 | Community | 1 | 75 g | 201 | 529 | 38.0 |

| Al-Shawaf et al., 1988 | Saudi Arabia | WHO | WHO 1985 | Hospital | 2 | 75 g | 41 | 1102 | 3.7 |

| Aziz et al., 2017 | India | CC | CC | Hospital | 1 | 100 g | 56 | 700 | 8.0 |

| Bener et al., 2011 | Qatar | WHO | WHO 2006 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 262 | 1608 | 16.3 |

| Bhatt et al., 2015 | India | DIPSI | DIPSI | Community | 1 | 75 g | 94 | 989 | 9.5 |

| Cheuk et al., 2016 | Hong Kong | WHO | WHO 1999 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 169 | 520 | 32.5 |

| Chodick et al., 2010 | Israel | CC | CC | Community | 1 | 100 g | 11,270 | 185,416 | 6.1 |

| Dahiya et al., 2014 | India | DIPSI | DIPSI | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 35 | 500 | 7.0 |

| Das et al., 2004 | India | NDDG | NDDG | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 12 | 300 | 4.0 |

| De Seymour et al., 2016 | Singapore | WHO | WHO 1999 | Hospital | 1 | 160 | 909 | 17.6 | |

| Deerochanawong et al., 1996 | Thailand | WHO | WHO 1985 | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 75 g | 111 | 709 | 15.7 |

| Garshasbi et al., 2008 | Iran | CC | CC | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 124 | 1804 | 6.9 |

| Gracelyn and Saranya2016 | India | ADA | ADA 2014 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 59 | 500 | 11.8 |

| Haideagh et al., 2005 | Iran | CC | CC | Community | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 62 | 800 | 7.8 |

| Hariharan et al., 2017 | India | WHO | WHO 2013 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 16 | 135 | 11.9 |

| Herath et al., 2016 | Sri lanka | IADPSG | IADPSG | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 105 | 452 | 23.2 |

| Hirst et al., 2012 | Vietnam | IADPSG | IADPSG | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 550 | 2702 | 20.4 |

| Hossain et al., 2017 | Pakistan | DIPSI | DIPSI | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 78 | 1030 | 7.6 |

| Hossein-Nezhad et al.,2007 | Iran | CC | CC | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 114 | 2416 | 4.7 |

| Iqbal et al., 2007 | Pakistan | ADA | ADA 2004 | Hospital | 2 | 75 g, 100 g | 49 | 612 | 8.0 |

| Jadhav and Wankhede 2017 | India | DIPSI | DIPSI | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 80 | 1000 | 8.0 |

| Jang et al., 1998 | South Korea | NDDG | NDDG | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 173 | 8863 | 2.0 |

| Jesmin et al., 2014 | Bangladesh | WHO | WHO 1999 | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 75 g | 112 | 1149 | 9.7 |

| Kalra et al., 2013 | India | DIPSI | DIPSI | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 33 | 500 | 6.6 |

| Kalyani et al., 2014 | India | WHO | WHO 1999 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 25 | 300 | 8.3 |

| Khwaja et al., 1989 | Saudi Arabia | WHO | WHO 1985 | Hospital | 1 | 50 g | 50 | 455 | 11.0 |

| Koo et al., 2016 | South Korea | ICD-10 | ICD-10 | Community | 98,403 | 1,306,281 | 7.5 | ||

| Krishnaveni et al., 2007 | India | CC | CC | Hospital | 1 | 100 g | 21 | 524 | 4.0 |

| Leng et al., 2016 | China | IADPSG | IADPSG | Community | 2 | 50 g, 75 g | 840 | 11,450 | 7.3 |

| Li et al., 2014 | China | ADA | ADA 2012 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 69 | 539 | 12.8 |

| Li et al., 2016 | China | IADPSG | IADPSG | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 48 | 327 | 14.7 |

| Lin et al., 2015 | Taiwan | ADA | ADA undefined | Hospital | 1 | 75 g or 100 g | 51 | 132 | 38.6 |

| Maegawa et al., 2003 | Japan | JDS | JDS | Hospital | 2 | 50 g or 75 g | 22 | 749 | 2.9 |

| Makwana et al., 2017 | India | DIPSI | DIPSI | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 38 | 476 | 8.0 |

| Mizuno et al., 2016 | Japan | JDS | JDS | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 204 | 8874 | 2.3 |

| Mohammadzadeh et al., 2015 | Iran | CC | CC | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 62 | 1276 | 4.9 |

| Moradi et al., 2015 | Iran | WHO | WHO 2006 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 44 | 290 | 15.2 |

| Mustafa 2015 | Bangladesh | WHO | WHO 1999 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 102 | 1489 | 6.9 |

| Nayak et al., 2013 | India | IADPSG | IADPSG | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 83 | 304 | 27.3 |

| Nielsen et al., 2016 | India | DIPSI | DIPSI | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 659 | 4053 | 16.3 |

| Parhofer et al., 2013 | Turkmenistan | ADA | ADA undefined | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 75 g | 109 | 1620 | 6.7 |

| Pirjani et al.,2016 | Iran | ADA | ADA 2012 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 78 | 256 | 30.5 |

| Raja et al., 2014 | India | DIPSI | DIPSI | Community | 1 | 75 g | 24 | 306 | 7.8 |

| Rajput et al., 2013 | India | ADA | ADA 2004 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 43 | 607 | 7.1 |

| Rajput et al., 2014 | India | WHO | WHO 1999 | Community | 1 | 75 g | 127 | 913 | 13.9 |

| Rao et al., 2015 | India | DIPSI | DIPSI | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 5 | 200 | 2.5 |

| Saisho et al., 2013 | Japan | JDS | JDS | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 75 g | 15 | 62 | 24.2 |

| Sayeed et al., 2005 | Bangladesh | WHO | WHO 1999 | Community | 1 | 75 g | 12 | 147 | 8.2 |

| Sella et al., 2011 | Israel | CC | CC | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 11,264 | 185,315 | 6.1 |

| Sella et al., 2013 | Israel | ADA | ADA 2003 | Community | 1 | 100 g | 14,288 | 367,247 | 3.9 |

| Shahbazian et al.,2016 | Iran | IADPSG | IADPSG | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 224 | 750 | 29.9 |

| Shaman et al., 2015 | Saudi Arabia | IADPSG | IADPSG | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 175 | 850 | 20.6 |

| Shamsuddin et al., 2001 | Malaysia | WHO | WHO 1985 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 191 | 768 | 24.9 |

| Shang et al., 2014 | China | IADPSG | IADPSG | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 612 | 3083 | 19.9 |

| Sharma et al., 2016 | India | IADPSG | IADPSG | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 74 | 417 | 17.7 |

| Shimodaira et al., 2016 | Japan | ADA | ADA 2004 | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 75 g | 149 | 5424 | 2.7 |

| Shrestha and Chawla 2011 | Nepal | CC | CC | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 12 | 1598 | 0.8 |

| Shridevi et al., 2015 | India | DIPSI | DIPSI | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 75 g | 23 | 200 | 11.5 |

| Singh and Uma 2013 | India | DIPSI | DIPSI | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 23 | 400 | 5.8 |

| Siribaddana et al., 1998 | Sri lanka | WHO | WHO 1985 | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 75 g | 40 | 721 | 5.5 |

| Soheilykhak et al., 2010 | Iran | CC | CC | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 110 | 1071 | 10.3 |

| Song et al., 2017 | China | IADPSG | IADPSG | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 1005 | 6886 | 14.6 |

| Srichumchit et al., 2015 | Thailand | NDDG | NDDG | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 1350 | 21,771 | 6.2 |

| Sudasinghe et al., 2016 | Sri lanka | WHO | WHO 1999 | Community | 1 | 75 g | 194 | 1400 | 13.9 |

| Suntorn and Panichkul 2015 | Thailand | IADPSG | IADPSG | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 71 | 325 | 21.8 |

| Swaroop et al., 2015 | India | DIPSI | DIPSI | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 22 | 225 | 9.8 |

| Tan et al., 2009 | Malaysia | WHO | WHO 1999 | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 75 g | 168 | 1368 | 12.3 |

| Thapa et al., 2015 | Nepal | WHO | WHO 1999 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 14 | 564 | 2.5 |

| Thathagari et al., 2016 | India | NDDG | NDDG | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 42 | 800 | 5.3 |

| Tran et al., 2013 | Vietnam | WHO | WHO 1999 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 674 | 2772 | 24.3 |

| Tripathi et al., 2011 | India | CC | CC | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 10 | 700 | 1.4 |

| Vakili et al., 2016 | Iran | ADA | ADA 2004 | Community | 1 | 75 g | 328 | 1209 | 27.1 |

| Wagaarachchi et al., 2001 | Sri lanka | WHO | WHO 1980 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 41 | 1004 | 4.1 |

| Wahabi et al., 2017 | Saudi Arabia | WHO | WHO 2013 | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 2354 | 9723 | 24.2 |

| Warunpitikul and Aswakul 2014 | Thailand | CC | CC | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 340 | 1363 | 24.9 |

| Yang et al., 2013 | South Korea | CC | CC | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 100 g | 269 | 1163 | 23.1 |

| Zargar et al., 2004 | India | CC and WHO | CC and WHO 1999 | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 75 g/100 g | 75 | 2000 | 3.8 |

| Zhang et al., 2011 | China | WHO | WHO 1999 | Hospital | 2 | 50 g, 75 g | 4764 | 105,473 | 4.5 |

| Zhang et al., 2015 | China | IADPSG | IADPSG | Community | 2 | 50 g, 75 g | 1069 | 14,198 | 7.5 |

| Zhu et al., 2017 | China | CHINA MOH | CHINA MOH | Hospital | 1 | 75 g | 2987 | 14,986 | 19.9 |

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: SMC, KWL. Performed the data extraction: KWL, AY. Analysed the data: KWL, SMC, AY, HFK, and VR. Quality Appraisal: YCC, WAWS, SS, MHM and SKV. Wrote the paper: SMC and KWL. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article contains only studies that comply with ethical standards. All of the eligible articles included in the meta-analysis stated that they had obtained informed consent from participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kai Wei Lee, Email: lee_kai_wei@yahoo.com.

Siew Mooi Ching, Email: sm_ching@upm.edu.my.

Vasudevan Ramachandran, Email: vasudevan@upm.edu.my.

Anne Yee, Email: annyee17@um.edu.my.

Fan Kee Hoo, Email: fan_kee@upm.edu.my.

Yook Chin Chia, Email: ycchia@sunway.edu.my.

Wan Aliaa Wan Sulaiman, Email: wanaliaa@upm.edu.my.

Subapriya Suppiah, Email: subapriya@upm.edu.my.

Mohd Hazmi Mohamed, Email: mdhazmi@upm.edu.my.

Sajesh K. Veettil, Email: sajesh_kalkandi@imu.edu.my

References

- 1.Metzger BE, Coustan DR, Committee O Summary and recommendations of the fourth international workshop-conference on gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:B161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendland EM, Torloni MR, Falavigna M, Trujillo J, Dode MA, Campos MA, et al. Gestational diabetes and pregnancy outcomes-a systematic review of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy study groups (IADPSG) diagnostic criteria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guariguata L, Linnenkamp U, Beagley J, Whiting D, Cho N. Global estimates of the prevalence of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(2):176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gasim T. Gestational diabetes mellitus: maternal and perinatal outcomes in 220 Saudi women. Oman Med J. 2012;27(2):140. doi: 10.5001/omj.2012.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanguru L, Bezawada N, Hussein J, Bell J. The burden of diabetes mellitus during pregnancy in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):23987. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.23987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Hakeem MM. Pregnancy outcome of gestational diabetic mothers: experience in a tertiary center. J Fam Commun Med. 2006;13(2):55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Group HSCR Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1991–2002. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpenter MW. Gestational diabetes, pregnancy hypertension, and late vascular disease. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Supplement 2):S246–SS50. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillier TA, Pedula KL, Vesco KK, Schmidt MM, Mullen JA, LeBlanc ES, et al. Excess gestational weight gain: modifying fetal macrosomia risk associated with maternal glucose. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):1007–1014. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818a9779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauth J, Clifton R, Roberts J, Myatt L, Spong C, Leveno K, et al. Maternal insulin resistance and preeclampsia. Obstet Anesth Dig. 2012;32(1):42–43. doi: 10.1097/01.aoa.0000410805.16137.2a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McIntyre HD. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome (HAPO) study: preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(3):255–e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Dudley DJ. Diabetic-associated stillbirth: incidence, pathophysiology, and prevention. Clin Perinatol. 2007;34(4):611–626. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilliod RA, Page JM, Burwick RM, Kaimal AJ, Cheng YW, Caughey AB. The risk of fetal death in nonanomalous pregnancies affected by polyhydramnios. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(3):410. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.10.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(10):1862–1868. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yogev Y, Xenakis EM, Langer O. The association between preeclampsia and the severity of gestational diabetes: the impact of glycemic control. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(5):1655–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchetti D, Carrozzino D, Fraticelli F, Fulcheri M, Vitacolonna E. Quality of life in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:12. Article ID 7058082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Bellamy L, Casas J-P, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9677):1773–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Retnakaran R, Qi Y, Connelly PW, Sermer M, Zinman B, Hanley AJ. Glucose intolerance in pregnancy and postpartum risk of metabolic syndrome in young women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(2):670–677. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carr DB, Utzschneider KM, Hull RL, Tong J, Wallace TM, Kodama K, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus increases the risk of cardiovascular disease in women with a family history of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):2078–2083. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah BR, Retnakaran R, Booth GL. Increased risk of cardiovascular disease in young women following gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(8):1668–1669. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Retnakaran R, Shah BR. Mild glucose intolerance in pregnancy and risk of cardiovascular disease: a population-based cohort study. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181(6–7):371–376. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan SD, Umans JG, Ratner R. Gestational diabetes: implications for cardiovascular health. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12(1):43–52. doi: 10.1007/s11892-011-0238-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clausen TD, Mathiesen ER, Hansen T, Pedersen O, Jensen DM, Lauenborg J, et al. High prevalence of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes in adult offspring of women with gestational diabetes mellitus or type 1 diabetes: the role of intrauterine hyperglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(2):340–346. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langer O, Yogev Y, Most O, Xenakis EM. Gestational diabetes: the consequences of not treating. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(4):989–997. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seshiah V, Das A, Balaji V, Joshi SR, Parikh M, Gupta S. Gestational diabetes mellitus-guidelines. JAPI. 2006;54:622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eades CE, Cameron DM, Evans JM. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Europe: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;129:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mwanri AW, Kinabo J, Ramaiya K, Feskens EJ. Gestational diabetes mellitus in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and metaregression on prevalence and risk factors. Tropical Med Int Health. 2015;20(8):983–1002. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alfadhli EM, Osman EN, Basri TH, Mansuri NS, Youssef MH, Assaaedi SA, et al. Gestational diabetes among Saudi women: prevalence, risk factors and pregnancy outcomes. Ann Saudi Med. 2015;35(3):222. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2015.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen CL, Pham NM, Binns CW, Duong DV, Lee AH. Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Eastern and Southeastern Asia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:10. Article ID 6536974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Wahi P, Dogra V, Jandial K, Bhagat R, Gupta R, Gupta S, et al. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and its outcomes in Jammu region. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59(4):227–30. [PubMed]

- 31.Adam S, Rheeder P. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus in a south African population: prevalence, comparison of diagnostic criteria and the role of risk factors. S Afr Med J. 2017;107(6):523–527. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i6.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harper LM, Mele L, Landon MB, Carpenter MW, Ramin SM, Reddy UM, et al. Carpenter-Coustan compared with National Diabetes Data Group criteria for diagnosing gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(5):893. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lauring JR, Kunselman AR, Pauli JM, Repke JT, Ural SH. Comparison of healthcare utilization and outcomes by gestational diabetes diagnostic criteria. J Perinat Med. 2018;46(4):401–409. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2017-0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corrado F, Pintaudi B. Diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus: Italian perspectives on risk factor-based Screening. In: Nutrition and diet in Maternal diabetes. Cham: Humana Press; 2018. p. 87–97.

- 35.Huvinen E, Eriksson JG, Koivusalo SB, Grotenfelt N, Tiitinen A, Stach-Lempinen B, et al. Heterogeneity of gestational diabetes (GDM) and long-term risk of diabetes and metabolic syndrome: findings from the RADIEL study follow-up. Acta Diabetol. 2018;55:493–501. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Xiao Y, Chen R, Chen M, Luo A, Chen D, Liang Q, et al. Age at menarche and risks of gestational diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Oncotarget. 2018;9(24):17133. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Idiopathic B, Endocrinopathies D. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:S5–S20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seshadri R. American diabetes association gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:S94–SS6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2007.S94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Association AD Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(suppl 1):s5–s10. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Association AD Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Suppl 1):S62. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Association AD Standards of medical care in diabetes--2012. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:S11. doi: 10.2337/dc12-s011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Association AD Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Supplement 1):S14–S80. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Organization WH . World Health Organization expert committee on diabetes mellitus: second report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.KGMM A, Pf Z. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15(7):539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Organization WH Diabetes mellitus World Health Organization. Tech Rep Ser. 1985;729:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Organization WH . Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycaemia: report of a WH. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 47.WHO. Diagnostic criteria and classification of hyperglycaemia first detected in pregnancy. 2013. [PubMed]

- 48.Clinical Practice CDA. Guidelines for the prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes. 2008;32(Suppl 1).

- 49.O'Sullivan JB, Mahan CM. Criteria for the oral glucose tolerance test in pregnancy. Diabetes. 1964;13:278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Group NDD Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 1979;28(12):1039–1057. doi: 10.2337/diab.28.12.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carpenter MW, Coustan DR. Criteria for screening tests for gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;144(7):768–773. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach. Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of diabetes (EASD) Diabetologia. 2012;55(6):1577–1596. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Obstetricians ACo, Gynecologists Screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):751–753. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182310cc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoffman L, Nolan C, Wilson JD, Oats JJ, Simmons D. Gestational diabetes mellitus-management guidelines-the Australasian diabetes in Pregnancy Society. Med J Aust. 1998;169(2):93–97. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb140192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.IAo D, Panel PSGC. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):676–682. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]