Abstract

BACKGROUND

Infliximab original has changed the natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) over the past two decades. However, the recent expiration of its patent has allowed the entry of the first Infliximab biosimilar into the European and Spanish markets. Currently switching drugs data in IBD are limited.

AIM

To compare the efficacy of infliximab biosimilar, CT-P13, against infliximab original, analyzing the loss of response of both at the 12 mo follow-up in patients with IBD.

METHODS

An observational study of two cohorts has been conducted. One retrospective cohort that included patients with IBD treated with Infliximab original, and a prospective cohort of patients who were switching from infliximab original to infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13). We had analyzed the overall efficacy and loss of efficacy in patients in remission at the end of one year after treatment with the original drug compared to the results of the year of treatment with the biosimilar.

RESULTS

98 patients (CD 67, CU 31) were included in both cohorts. The overall efficacy for infliximab original per year of treatment was 71% vs 68.2% for infliximab biosimilar (P = 0.80). The loss of overall efficacy at 12 mo for infliximab original was 6.6% vs 14.5% for infliximab biosimilar (P = 0.806). The loss of efficacy in patients who were in basal remission was 16.3% for infliximab original vs 27.1% for infliximab biosimilar. Adverse events were 9.2% for infliximab original vs 11.2% for infliximab biosimilar.

CONCLUSION

The overall efficacy and loss of treatment response with infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13) is similar to that observed with infliximab original in patients who were switching at the 12 mo follow-up. There is no difference in the rate of adverse events.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative colitis, CT-P13, Inflammatory bowel disease, Biosimilar agent, Infliximab original, Efficacy

Core tip: Although not strictly necessary, there are few studies comparing efficacy and safety of the switch from infliximab original (Remicade®) to infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 vs the maintenance of the original infliximab. For this reason, we presented a comparative study with the original infliximab. Our observational study demonstrates the real-life clinical results of efficacy and safety of infliximab original and the efficacy and safety after switching from original infliximab to infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 at the 12 mo follow-up. Our results demonstrate there is no statistical difference in remission rate, secondary loss of response or adverse events between both therapies.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic gastrointestinal disorder of unknown etiology which causes deterioration in the quality of life of the patient[1]. The introduction of biological therapies two decades ago, particularly anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha drugs[2,3], has revolutionized the therapeutic approach of IBD, especially in those patients with severe or refractory disease[2]. Despite the undoubted efficacy of biological therapy, these biological agents are much more expensive than traditional treatments, and so impose a considerable burden on the national healthcare system[4]. However, many biological products have reached or are close to patent expiration. This has led to the development of biosimilar drugs[5-7].

CT-P13 (Remsima® and Inflectra®) was the first biosimilar of infliximab approved by the European Medicines Agency[8] in September 2013 and by the United States Food and Drug Administration (United States FDA)[9] in April 2016 for all indications of the originator product including IBD. The extrapolation of use of biosimilar infliximab was based on two phase III clinical trials in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (PLANETRA)[10] and ankylosing spondylitis (AS) (PLANETAS)[11]. Both studies at 30 wk proved the similarity of infliximab biosimilar against the reference product (Remicade®) in terms of efficacy, safety and immunogenicity. Furthermore, the results of the 102 wk open label extensions of PLANETAS[11] and PLANETRA[10] trials have been recently published, providing important information about the safety, efficacy and immunogenicity of switching from infliximab original to infliximab biosimilar in both AS and RA patients[12,13].

During these years, some observational studies and real-life cohorts have been published on the efficacy and safety of the infliximab biosimilar in IBD[14-25]. Although not strictly necessary, there are few studies comparing efficacy and safety of the switch from infliximab original (Remicade®) to infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 vs the maintenance of the infliximab original[26,27]. One of the few studies that provide relevant evidence is the results of the phase IV, double-blind, parallel-group NOR-SWITCH study[27]. This trial proved that switching from infliximab RP to CT-P13 was not inferior to continued treatment with infliximab RP. However, this study has received much criticism because of its methodological limitations and is not powered to perform a subgroup analysis, especially IBD patients[28].

Despite initial concerns about infliximab biosimilar not having enough data about safety, security and immunogenicity, guidance from inflammatory bowel disease societies has gradually moved towards a positive and confident position on CT-P13. The European Crohn’s Colitis Organization (ECCO) published its position statement on the use of biosimilars for IBD in December 2016 which states that “when a biosimilar product is registered in the European Union, it is considered to be as efficacious as the reference product when used in accordance with the information provided in the Summary of Product Characteristics”[29].

For all the above, this study is designed to compare the efficacy of infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 against infliximab original, analyzing the loss of response of both at the 12 mo follow-up in patients with IBD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was an observational study of two cohorts conducted at the Virgen Macarena Hospital (Seville, Spain). One retrospective cohort that included patients with IBD treated with infliximab original from January 2014 to December 2014, and one prospective cohort with patients who were switching from infliximab original to infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13) from March 2015 to February 2016. We had analyzed the overall efficacy and loss of efficacy in patients in remission at the end of one year after treatment with the original product compared to the results of the year of treatment with infliximab biosimilar. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Virgen Macarena Hospital. Good clinical practice guidelines were followed and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Patients

In the retrospective cohort we included all the patients with CD or UC who were treated with infliximab original at least once in 2014. In the prospective cohort we included all the patients with CD or UC who had been switching from infliximab original to infliximab biosimilar and had completed a 12 mo follow-up. Montreal classification status was recorded in all patients before enrolment.

Study endpoints and assessments

The efficacy endpoint was the change in clinical remission in patients with infliximab original, and in patients switched from infliximab RP to CT-P13 assessed at 12 mo.

In patients with CD and UC remission was considered when: (1) Harvey-Bradshaw score (HB) ≤ 4 in patients with CD or partial Mayo score ≤ 2 in patients with UC; (2) C-reactive protein (CRP) ≤ 5 mg/dL; (3) no use of steroids; (4) no surgery related to the disease activity; and (5) no increased dosage at the established follow-up time.

Adverse events (AE) were monitored from the first infusion of CT-P13 until the end of the study and they were recorded according to the Office of Human Research Protection.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and nominal results were reported in percentages and frequencies. Numerical results were reported as average and standard deviation in cases of normal distribution and as median and interquartile range (IQR) in cases of asymmetrical distribution. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare the clinical scores (HB Score and partial Mayo Score) and the CRP values of patients. McNemar’s test and the Cochran Q test were used to compare both groups’ remission. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated and α was set at 0.05 for the determination of statistical significance. Analysis was performed using SPSS 23 (IBM Corporation).

RESULTS

A total of 98 patients were included in each cohort. 68.4% (n = 67) were CD, and 31.6% (n = 31) were UC.

Retrospective cohort

The median age of patients was 39.9 (standard deviation SD 12.5 years old), (95%CI: 37.4-42.4). Over half of the patient population (55.4%) were men and 70.4% were non-smokers. Median time of the disease before starting the follow-up was 44 [Interquartile range (IQR) = 18; 100 mo]. Median duration of ongoing infliximab original treatment at the start of the study was 55 (IQR = 28.7; 72 mo). 40.8% used concomitant thiopurines before starting the follow-up. The baseline demographics and phenotypic characteristics of patients with CD and UC according to the Montreal classification are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative baseline demographics and phenotypic characteristics of patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in both groups n (%)

| Prospective cohort | 95%CI | Retrospective cohort | 95%CI | P value | ||

| Characteristics (n = 98) | ||||||

| Sex | men | 51 (52) | 41.6-62.4 | 56 (57.1) | 46.8-67.4 | |

| women | 47 (48) | 37.6-58.4 | 42 (42.9) | 32.5-53.2 | 0.280 | |

| Smoking status | Never | 67 (68.3) | 58.7-78.1 | 69 (70.4) | 60.9-79.9 | |

| Previous | 18 (18.4) | 10.2-26.5 | 16 (16.3) | 8.5-24.1 | 0.929 | |

| Current | 13 (13.3) | 6.0-20.5 | 13 (13.3) | 6.1-20.5 | ||

| Crohn’s disease (n = 67) | ||||||

| Age at diagnosis | A1 (< 17) | 7 (10.5) | 2.4-18.5 | 10 (15) | 5.6-24.2 | |

| A2 (17-40) | 49 (73.1) | 61.8-84.5 | 48 (71.6) | 60.1; 83.2 | 0.691 | |

| A3 ( > 40) | 11 (16.4) | 6.8-26.0 | 9 (13.4) | 4.5; 22.3 | ||

| Location at diagnosis | L1 (ileal) | 18 (26.9) | 15.5-38.2 | 15 (22.4) | 11.7-33.1 | |

| L2 (colonic) | 26 (38.8) | 26.4-51.2 | 25 (37.3) | 25.0-49.6 | 0.887 | |

| L3 (ileocolonic) | 21 (31.3) | 19.5-43.2 | 25 (37.3) | 25.0-49.6 | ||

| L4 (upper gastrointestinal tract) | 2 (3.0) | 0.3-10.4 | 2 (3.0) | 0.4-10.4 | ||

| Disease behavior | B1 (non-stricturing, non-penetrating) | 38 (56.7) | 44.169.3 | 39 (58.2) | 45.7-70.8 | 0.860 |

| B2 (stricturing) | 14 (20.9) | 10.4-31.4 | 13 (19.4) | 9.2-29.6 | ||

| B3 (penetrating) | 15 (22.4) | 11.7-33.1 | 15 (22.4) | 11.7-33.1 | ||

| Perianal disease | Yes | 37 (55.2) | 42.6-67.9 | 39 (58.2) | 45.7-70.8 | 0.727 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | No | 42 (62.7) | 50.4-75.0 | 46 (68.7) | 56.8-80.5 | 0.466 |

| Ulcerative colitis (n = 31) | ||||||

| Extension | ||||||

| E1 (proctitis) | 13 (41.9) | 22.9-60.9 | 12 (38.7) | 19.9-57.5 | ||

| E2 (left colitis) | 10 (32.3) | 14,2-50.3 | 11 (35.5) | 17.0-53.9 | 0.957 | |

| E3 (pancolitis) | 8 (25.8) | 8.8-42.9 | 8 (25.8) | 8.8-42.9 | ||

| Severity | S1 (mild) | 11 (35.5) | 17.0-53.9 | 10 (32.3) | 14.2-50.3 | |

| S2 (moderate) | 16 (51.6) | 32.4-70.8 | 17 (54.8) | 35.7-74.0 | 0.962 | |

| S3 (severe) | 4 (12.9) | 3.6-29.8 | 4 (12.9) | 3.6-29.8 | ||

| Extraintestinal manifestations | No | 26 (83.9) | 66.3-94.5 | 27 (87.1) | 66.3-94.5 | 0.500 |

| Prior treatment | 75 (76.5) | 67.6-85.4 | 85 (86.7) | 79.5-94 | 0.097 | |

| Thiopurines | 25 (25.5) | 16.4-34.7 | 25 (25.5) | 16.4-34.7 | 0.970 | |

| Methotrexate | ||||||

| Concomitant treatment | 50 (51) | 40.6-61.4 | 40 (40.8) | 30.6-51.1 | 0.197 | |

| Thiopurines | 8 (8) | 2.2-14.1 | 7 (7,1) | 1.1-10,1 | 0.999 | |

| Methotrexate | ||||||

At the start of the study the global remission was 77.6% (76/98) (95%CI: 68.8-86.3) and 71% (66/93) (95%CI: 61.2-80.7) at the 12 mo follow-up. In total, 76 patients were in remission at the time of switch, 83.7% (62/74) (95%CI: 74.7-92.9) had remained in remission at 12 mo of follow-up.

Five patients discontinued treatment (two endoscopic mucosa healing, three adverse effects including development of cervical neoplasia).

CD

In the CD patient group, the median age was 37 (IQR = 30; 47 years). The median time of treatment with infliximab original before starting the follow-up was 59 (IQR = 30; 78 mo). The locations at diagnostic were colonic in 37.3%, with non-stricturing, non-penetrating behavior in 58.2%. 46.3% used concomitant thiopurines before starting the follow-up.

Of the 67 patients analyzed, the basal remission was 76.1% (51/67) (95%CI: 65.2-87.1) and 69.2% (45/65) (95%CI: 57.2-81.2) at the 12 mo follow-up. Of the 51 patients who were in initial remission this was maintained in 82.3% (42/51) (95%CI: 70.9-93.8) of patients at the 12 mo follow-up. Two patients discontinued treatment: Two adverse effects including development of a cervix neoplasia.

The HB score showed significant changes over the 12 mo period [median HB score 95%CI: 1 (0-2) vs 1 (1-3) at month 0 and 12, P = 0.005]. No significant changes were observed in median of CRP levels [1.0 (0-5) vs 0.4 (0.2-2) at 0 and 12 mo, P = 0.464].

Ulcerative colitis

In the UC patient, the median time of treatment with infliximab original before starting the follow-up was 42 (IQR = 20; 60 mo). The locations at diagnostic were proctitis in 38.7% with a moderate severity in 54.8%.

Of the 31 patients analyzed, the basal remission was 80.6% (25/31) (95%CI: 62.5-92.5), and 75% (21/28) (95%CI: 57.2-92.8) at the 12 mo follow-up. Of the 25 patients who were in initial remission this was maintained in 87% (20/23) (95%CI: 70.9-93.8) of patients at the 12 mo follow-up. Three patients discontinued treatment: (two endoscopic mucosa healing and one adverse effect).

No significant changes in the median (95%CI) partial Mayo score were observed in switched patients over the 12 mo [2 (1-3); vs 1 (1-3) at 0; P = 0.067]. No significant changes in the median CRP level (95%CI) were observed over the same period [2 (1-10) vs 0.6 (0.2-5.5) at months 0 and 12, P = 0.654].

Prospective cohort

The median age of patients was 41 (SD 12.7 years). Over half of the patient population (56.1%) were men and 68.3% were non-smokers. Median time of the disease before starting the follow-up was 100 (IQR = 77; 151 mo). Median duration of ongoing infliximab original treatment at the start of the study was 60.7 (IQR = 10.5; 73.5 mo). 51% used concomitant thiopurines before starting the follow-up. The baseline demographics and phenotypic characteristics of patients with CD and UC according to the Montreal classification are shown in Table 1.

Of the 98 patients analyzed, 82.7% (81/98) (95%CI: 74.6-90.7) were in remission at the beginning of the study, and 68.2% (60/88) (95%CI: 57.9-78.5) at the 12 mo follow-up. Of the 81 patients who were in initial remission this was maintained in 72.9% (54/74) (95%CI: 62.2-83.8) of patients at 12 mo.

Ten patients discontinued treatment (3 endoscopic mucosal remission, 6 adverse effects, 1 patient did not attend follow-up visits).

Crohn´s disease

In the CD patient, median time of treatment with infliximab original before starting the follow-up was 74.3 (IQR = 41; 108 mo). The location at diagnostic was colonic in 38.3%, with non-stricturing, non-penetrating behavior in 56.7%, and 55% had perineal disease. 56.7% used concomitant thiopurines before starting the follow-up.

Of the 67 patients analyzed, the basal remission was 83.6% (56/67) (95%CI: 87.3-93.2) and 67.7% (42/62) (95%CI: 55.3-80.2) at the 12 mo follow-up. Of the 56 patients who were in initial remission this was maintained in 69.8% (37/53) (95%CI: 56.5-83.1) of patients at the 12 mo follow-up (P = 0.634). 92.5% (62/67) patients completed the follow-up.

Five patients discontinued treatment: Four adverse effects, one patient did not attend follow-up visits.

The HB score showed significant changes over the 12 mo period [median HB score 95%CI: 1 (1-2) vs 1 (1-3) at months 0 and 12, P = 0.007]. No significant changes were observed in median of CRP levels [1.0 (0-6) vs 0.36 (0.2-2) at 0 and 12 mo (P = 0.364)].

Ulcerative colitis

In the UC patient, the median time of treatment with infliximab original before starting the follow-up was 52 (IQR = 20; 60 mo). The location at diagnostic was left in 41.9% with a moderate severity in 51.6%.

Of the 31 patients analyzed, the basal remission was 80.6% (25/31) (95%CI: 62.5-92.5), and 69.2% (18/26) (95%CI: 49.6-88.9) at the 12 mo follow-up. Of the 25 patients who were in initial remission this was maintained in 81% (17/21) (95%CI: 62.5.9-92.5) of patients at the 12 mo follow-up. Five patients discontinued treatment: Three endoscopic mucosa healing and two adverse effects.

No significant changes in the median (95%CI) partial Mayo score were observed in switched patients over the 12 mo [2 (1-3) vs 1 (0-3) at month 0 and 12, P = 0.058]. No significant changes in the median CRP level (95%CI) were observed over the same period [2 (1-10) vs 0.6 (0.2-1.4) at month 0 and 12, P = 0.329].

Comparison analysis

The basal remission rate of the infliximab original group was 77.6% vs 82.7% of infliximab biosimilar (P = 0.474). At 12 mo the remission rate was 71% in infliximab original vs 68.2% of biosimilar infliximab (P = 0.806) without achieving statistical significance. This is showed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of efficacy and loss of efficacy in both groups

| Infliximab original Group | 95%CI | CT-P13 Group | 95%CI | P value | Rate difference (95%CI) | |

| Basal global remission | 76/98 (77.6%) | 66.8-86.3 | 81/98 (82.7%) | 74.6-90.7 | 0.474 | -0.173-0.071 |

| Global remission 12 mo | 66/93 (71%) | 61.2-80.7 | 60/88 (68.2%) | 51.1-71.4 | 0.806 | -0.117-0.173 |

| Basal remission CD | 51/67 (76.1%) | 65.2-87.1 | 56/67 (83.6%) | 73.9-93.2 | 0.389 | -0.225-0.076 |

| Remission 12 mo CD | 45/65 (69.2%) | 57.2-81.2 | 42/62 (67.7%) | 55.3-80.2 | 0.992 | -0.163-0.192 |

| Basal UC remission | 25/31 (80.6%) | 62.5-92.5 | 25/31 (80.6%) | 62.5-92.5 | 0.748 | -0.29-0.229 |

| Remission 12 mo UC | 21/28 (75%) | 57.2-92.8 | 18/26 (69.2%) | 49.6-88.9 | 0.866 | -0.219-0.334 |

UC: Ulcerative colitis. CD: Crohn’s disease.

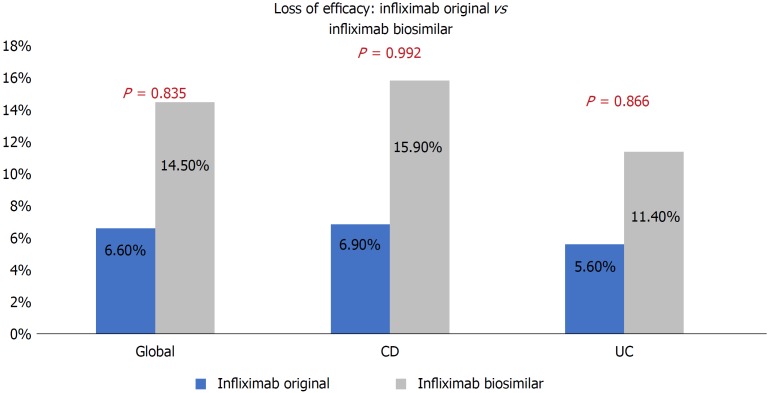

The loss of overall efficacy at 12 mo in the infliximab original group was 6.6% and 14.5% in the infliximab biosimilar group, without achieving statistical significance (P = 0.835). There were not statistically significant differences observed when comparing the loss of efficacy by type of disease, CD (P = 0.992) and UC (P = 0.866, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Loss of efficacy at 12 mo in both groups.

When we analyzed patients, who were in basal remission, the loss of efficacy was 16.3% in the infliximab original vs 27.1% in the infliximab biosimilar at the 12 mo follow-up, without statistical differences (P = 0.162). There were also no statistically significant differences when we analyzed by type of disease CD (P = 0.205) and UC (P = 0.890, Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparative of maintenance of remission at 12 mo in patients with initial remission in both groups

| Infliximab original group | 95%CI | CT-P13 group | 95%CI | P value | Rate Difference (95%CI) | |

| Maintained basal remission at 12 mo | 62/74 (83.7%) | 74.7-92.9 | 54/74 (72.9%) | 62.2-83.5 | 0.162 | -0.037-0.253 |

| Maintained basal remission at 12 mo CD | 42/51 (82.3%) | 70.9-93.8 | 37/53 (69.8%) | 56.5-83.1 | 0.205 | -0.056-0.307 |

| Maintained basal remission at 12 mo UC | 20/23 (87%) | 66.4-97.2 | 17/21 (81.0%) | 62.5-92.5 | 0.890 | -0.203-0.23 |

CD: Crohn's disease; UC: Ulcerative colitis.

No significant changes in disease activity, measured by HB in CD (P = 0.385) and Partial Mayo score in UC (P = 0.349) were observed between both groups. Significant changes in the median CRP level (95%CI) were observed between both groups (P = 0.014), nevertheless, it was always in remission (≤ 5 mg/dL).

Safety

Retrospective cohort: 9 AEs occurred in 9/98 (9.2%) patients: One hypertensive crisis, three infusion reactions, one palpitations, one asthenia, one arthralgia, one HBV reactivation, one cervical carcinoma. Four patients discontinued treatment because of AEs. Severe adverse events were considered in a patient with UC for HBV reactivation that needed treatment and one CD patient who developed a cervical carcinoma.

Prospective cohort: 11 AEs occurred in 11/98 (11.2%) patients: One skin reaction, one case of abdominal pain, two cases of headache and two of paresthesia during infusion, one case of Sweet’s syndrome, two of polyarthralgia, and two of palpitations. Six patients discontinued treatment because of AEs. Severe adverse event was considered in one patient with CD who had Sweet’s syndrome needing hospitalization and discontinued treatment. In addition, one patient with UC discontinued because of paresthesia during the infusion.

There were not statistical differences between each group (P = 0.814, 95%CI: 0.115-0.075)

DISCUSSION

Despite initial concerns about infliximab biosimilar, different articles have proved the efficacy and safety of CT-P13. Also, the European Crohn´s Colitis Organization (ECCO) published its favorable position statement on the use of biosimilars for IBD in December 2016[29]. We recently have published three studies in this matter[15,24-25]. In these studies, we proved the efficacy of CT-P13, although our patients’ cohorts (switch cohort) have not been compared to a non-switch cohort. Many studies and practical clinical trials have proved the efficacy of anti-TNF-α in IBD[2-4]. However, up to 30% of patients show no clinical benefit after induction therapy (primary non-responders), and another 30%-40% lose response during the first year of treatment (secondary non-responders)[30], with an estimated annual risk of loss of efficacy between 13%-15% per patient/year[31]. Consequently, we wanted to explore whether our loss of efficacy in the switch cohort was similar to a non-switch cohort in our centre.

Our observational study proves the real-life clinical results of efficacy and safety of infliximab original and the efficacy and safety after switching from infliximab original to infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 at 12 mo follow-up. Our results prove there is no statistical difference in remission rate, secondary loss of response or adverse events between both therapies. Both groups had similar baseline characteristics. The basal remission in the infliximab original group was 77.6% vs 82.7% for infliximab biosimilar. At 12 mo, the infliximab original remission rate was 71% vs 68.2% for the infliximab biosimilar group. The loss of overall efficacy at 12 mo in the infliximab original group was 6.6% and 14.5% in the infliximab biosimilar one (P = 0.806). The loss of efficacy in patients who were in basal remission was 16.3% in the infliximab original vs 27.1% in the infliximab biosimilar. It is important to note that, although the difference in the loss of efficacy between the two groups (10.8%) is high, no statistical differences were observed. We believe that this difference may be caused by the fact that an insufficient number of patients were included in the study and that the intervals of confidence were so high that it was impossible to obtain a statistical difference.

In other hand, nocebo is a concept that should be taken into account in our results. Many patients did not have enough confidence in the biosimilar, and as it has been proved in some studies[32,33], nocebo can play a role in the efficacy of the switch cohort. Another important point to analyze is that, although present in both groups, the CD patients’ median of HB score showed significant changes over the 12 mo, but it never went over the definition of remission (≤ 4). In both groups, in UC patients the median partial Mayo score remained without changes, CRP levels remained without clinically relevant changes in both groups (≤ 5). We did not find changes in the clinical and analytical parameters, and so we believe that the strong nocebo effect in the biosimilar group explains this loss of efficacy.

In the NOR-SWITCH trial[27] the proportion of patients with disease worsening after six months of stable disease was 26.2% in the infliximab original arm and 29.6% in the CT-P13 arm, after 52 wk. The worsening of the disease happened more frequently in CD patients, however the authors concluded that switching from infliximab original to infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13) was not inferior to continued treatment with infliximab original regarding efficacy, safety and immunogenicity. Also, in the 26 wk open label NOR-SWITCH EXTENSION trial reported in the ECCO congress last February[34], safety and immunogenicity were assessed regarding CT-P13 treatment throughout the 78 wk study period (maintenance group) compared to switching from infliximab original to CT-P13 at week 52 (switch group). Overall disease worsening occurred in 16.8% of patients in the maintenance group and in 11.6% in the switch group. In CD, disease worsening occurred in 20.6% and 13.1% and in UC in 15.4% and 2.9% of patients in the maintenance and switch group, respectively. These results were within the non-inferiority margin (15%).

These results are similar in other studies. In the SECURE study[35] infliximab serum concentrations in adults with ulcerative colitis (n = 59) and Crohn’s disease (n = 61) were examined 16 wk after switching from infliximab original to CT-P13. Serum infliximab concentration with CT-P13 was not inferior to those with infliximab original. Furthermore, no significant changes were noted in clinical and biochemical variables, quality of life and tolerability[35]. In the PROSIT-BIO study[36] the efficacy estimations were 95.7%, 86.4%, and 73.7% for naive; 97.2%, 85.2%, and 62.2% for pre-exposed; and 94.5%, 90.8%, and 78.9% for switch at 8 wk, 16 wk, and 24 wk respectively. 12.1% of adverse events were reported, 38 (6.9%) of them being infusion-related reactions. In a prospective observational single center study[26], that included 191 patients who were switched from original infliximab to CT-P13 and 19 patients who continued with the original. They showed no statistical difference in remission (58.1% vs 47.4%, P = 0.37), response (12.6% vs 10.5%, P = 0.80), secondary loss of response (24.6% vs 42.1%, P = 0.10), or adverse events (4.7% vs 0, P = 1.0) between those who switched to CT-P13 and those who continued infliximab original at the 12 mo follow-up[26].

All data is in accordance with our results. All observational post-marketing studies published to date have reported positive outcomes for efficacy measures in patients with CD and UC treated with CT-P13, irrespective of prior anti-TNF-α treatment[14-26]

Finally, the recently published systematic review with meta-analysis[37], in patients with CD switching from infliximab RP to CT-P13 demonstrated high rates of sustained clinical response at 30-32 wk (0.85, 95%CI: 0.71-0.93) and 48-63 wk (0.75, 95%CI: 0.44-0.92) and high rates for sustained clinical remission 0.74 (95%CI: 0.55-0.87) and 0.92 (95%CI: 0.38-0.99), at 16 wk and 51 wk respectively.

In our study, 9.2% (9/98) of patients had drug-related adverse events with infliximab original, four patients discontinued the treatments for this reason. In the infliximab biosimilar 11.2% (11/98) of patients had drug-related adverse events, six patients discontinued treatment because of AEs. These data are related to the results of several studies on the rate of adverse events between 10%-20%.

Our study has some limitations. First of all, and perhaps most importantly, we analyzed a retrospective cohort of patients with infliximab original, which could be a methodological deficit with an error of data interpretation. Similarly, we could not measure calprotectine, drug trough levels, or the presence of antidrug antibodies as has been done in other studies, because at the time of the study these were not available in our hospital. Therefore, it has not been possible to ascertain the cause of the loss of response observed in some patients. We were also unable to measure mucosal healing or perform an endoscopy on any of the patients at the time of the study.

Despite the limitations in our study, we believe that it shows real data in clinical practice in the one-year follow-up. The loss of efficacy in patients in clinical remission treated with biosimilars was 10.8%, close to the margin of non-inferiority of 15% as other previously published studies[25-32]. We conclude that the overall efficacy and loss of treatment response with Infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13) is similar to that observed with Infliximab original in patients who were switching at the 12 mo follow-up.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Infliximab was the first monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor alpha approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (United States FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Despite the undoubted efficacy of this biological therapy, this biological agent is much more expensive than traditional treatments and, therefore, imposes a considerable burden on the national health system. However, with the recent expiration of its patent, biosimilar medicines have been developed. CT-P13 (Remsima® and Inflectra®) was the first biosimilar of infliximab approved by EMA and United States FDA for all indications of the originator product including IBD. The effectiveness in IBD is being debated due to the approval of this biosimilar was based on clinical trials in rheumatological diseases.

Research motivation

Some observational studies and real-life cohorts have been published on the efficacy and safety of the infliximab biosimilar in naive patients with IBD. Although not strictly necessary, there are few studies comparing efficacy and safety of the switch from infliximab original to infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 vs the maintenance of the infliximab original.

Research objectives

To compare the efficacy of infliximab biosimilar, against infliximab original, analyzing the loss of response of both at the 12 mo follow-up in patients with IBD

Research methods

An observational study of two cohorts has been conducted. One retrospective cohort that included patients with IBD treated with Infliximab original, and a prospective cohort of patients who were switching from infliximab original to infliximab biosimilar. 98 patients were included in each cohort. We had analyzed the overall efficacy and loss of efficacy in patients in remission at the end of one year after treatment with the original drug compared to the results of the year of treatment with the biosimilar. The efficacy was reported based clinical scores [Harvey-Bradshaw score (HB) ≤ 4 in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) or partial Mayo score ≤ 2 in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC)] and biochemical test. Wilcoxon test, McNemar´s test and the Cochran Q test were used to compare the variables in both periods.

Research results

This study demonstrated the overall efficacy and the loss of overall efficacy for infliximab original and infliximab biosimilar were similar per year of treatment.

The loss of efficacy in patients who were in basal remission was 16.3% in the infliximab original vs 27.1% in the infliximab biosimilar. This 10.8% of difference in the loss of efficacy between the two groups did not show a statistical difference. No significant changes in disease activity, measured by HB in CD (P = 0.385) and Partial Mayo score in UC (P = 0.349) were observed between both groups. Significant changes in the median CRP level (95%CI) were observed between both groups (P = 0.014), nevertheless, it was always in remission (≤ 5 mg/dL). Adverse events were similar in both cohorts.

Research conclusions

Our study suggests that the overall efficacy and loss of treatment response with infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13) is similar to that observed with infliximab original in patients who were switching at the 12 mo follow-up. The high difference in the loss of efficacy shown in patients who were in basal remission with infliximab original vs infliximab biosimilar could be explained by the following: in our data we found the intervals of confidence in both groups were so high that it was impossible to obtain a statistical difference, and in other hand, nocebo is a concept that should be taken into account in our results. Many patients did not have enough confidence in the biosimilar the first year.

Research perspectives

Future prospective comparative studies with long-term follow-up are necessary to discriminate the loss of efficacy in patient who were switched to infliximab biosimilar.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Andalusian Group of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Kern Pharma Biologics.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Virgen Macarena Hospital, Seville, Spain.

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: Guerra Veloz MF, Castro Laria L, Maldonado Pérez B, Perea Amarillo R and Argüelles-Arias F have received financial support to attend scientific meetings from Kern Pharma. Benítez Roldán A, Merino Bohórquez V, Calleja MA, Caunedo Álvarez Á, and Vilches Arenas Á do not have conflict of interest.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

STROBE statement: the guidelines of the STROBE Statement have been adopted

Peer-review started: August 29, 2018

First decision: October 14, 2018

Article in press: December 7, 2018

P- Reviewer: Matowicka-Karna J, Ribaldone DG, Vasudevan A S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yin SY

Contributor Information

María Fernanda Guerra Veloz, Department of Gastroenterology, University Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville 41007, Spain.

Federico Argüelles-Arias, Department of Gastroenterology, University Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville 41007, Spain. farguelles@telefonica.net.

Luisa Castro Laria, Department of Gastroenterology, University Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville 41007, Spain.

Belén Maldonado Pérez, Department of Gastroenterology, University Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville 41007, Spain.

Antonio Benítez Roldan, Department of Gastroenterology, University Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville 41007, Spain.

Raúl Perea Amarillo, Department of Gastroenterology, University Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville 41007, Spain.

Vicente Merino Bohórquez, Pharmacy Unit, University Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville 41007, Spain.

Miguel Angel Calleja, Pharmacy Unit, University Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville 41007, Spain.

Ángel Caunedo Álvarez, Department of Gastroenterology, University Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville 41007, Spain.

Ángel Vilches Arenas, Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville 41007, Spain.

References

- 1.Feuerstein JD, Cheifetz AS. Crohn Disease: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1088–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Côté-Daigneault J, Bouin M, Lahaie R, Colombel JF, Poitras P. Biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: what are the data? United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:419–428. doi: 10.1177/2050640615590302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tracey D, Klareskog L, Sasso EH, Salfeld JG, Tak PP. Tumor necrosis factor antagonist mechanisms of action: a comprehensive review. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;117:244–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodger K, Kikuchi T, Hughes D. Cost-effectiveness of biological therapy for Crohn's disease: Markov cohort analyses incorporating United Kingdom patient-level cost data. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:265–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Medicines Agency- New guide on biosimilar medicines for healthcare professionals. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2017/05/news_detail_002739.jspmid=WC0b01ac058004d5c1.

- 6.European Medicines Agency. Procedural advice for users of the centralized procedure for similar biological medicinal products applications. London, UK: European Medicines Agency;; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Medicines Agency. Guideline on similar biological medicinal products. London 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Medicines Agency. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) Assessment report: Remsima (infliximab); 2013. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/002576/WC500151486.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.INFLECTRA prescribing information. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/125544s000lbl.pdf.

- 10.Yoo DH, Hrycaj P, Miranda P, Ramiterre E, Piotrowski M, Shevchuk S, Kovalenko V, Prodanovic N, Abello-Banfi M, Gutierrez-Ureña S, et al. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study to demonstrate equivalence in efficacy and safety of CT-P13 compared with innovator infliximab when coadministered with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: the PLANETRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1613–1620. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park W, Hrycaj P, Jeka S, Kovalenko V, Lysenko G, Miranda P, Mikazane H, Gutierrez-Ureña S, Lim M, Lee YA, et al. A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group, prospective study comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of CT-P13 and innovator infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: the PLANETAS study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1605–1612. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoo DH, Prodanovic N, Jaworski J, Miranda P, Ramiterre E, Lanzon A, Baranauskaite A, Wiland P, Abud-Mendoza C, Oparanov B, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13 (biosimilar infliximab) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparison between switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 and continuing CT-P13 in the PLANETRA extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:355–363. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park W, Yoo DH, Miranda P, Brzosko M, Wiland P, Gutierrez-Ureña S, Mikazane H, Lee YA, Smiyan S, Lim MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 compared with maintenance of CT-P13 in ankylosing spondylitis: 102-week data from the PLANETAS extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:346–354. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung YS, Park DI, Kim YH, Lee JH, Seo PJ, Cheon JH, Kang HW, Kim JW. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13, a biosimilar of infliximab, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A retrospective multicenter study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1705–1712. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Argüelles-Arias F, Guerra Veloz MF, Perea Amarillo R, Vilches-Arenas A, Castro Laria L, Maldonado Pérez B, Chaaro D, Benítez Roldán A, Merino V, Ramírez G, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of CT-P13 (Biosimilar Infliximab) in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Real Life at 6 Months. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1305–1312. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4511-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gecse KB, Lovász BD, Farkas K, Banai J, Bene L, Gasztonyi B, Golovics PA, Kristóf T, Lakatos L, Csontos ÁA, Juhász M, Nagy F, Palatka K, Papp M, Patai Á, Lakner L, Salamon Á, Szamosi T, Szepes Z, Tóth GT, Vincze Á, Szalay B, Molnár T, Lakatos PL. Efficacy and Safety of the Biosimilar Infliximab CT-P13 Treatment in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Prospective, Multicentre, Nationwide Cohort. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:133–140. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park SH, Kim YH, Lee JH, Kwon HJ, Lee SH, Park DI, Kim HK, Cheon JH, Im JP, Kim YS, et al. Post-marketing study of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) to evaluate its safety and efficacy in Korea. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9 Suppl 1:35–44. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1091309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farkas K, Rutka M, Golovics PA, Végh Z, Lovász BD, Nyári T, Gecse KB, Kolar M, Bortlik M, Duricova D, et al. Efficacy of Infliximab Biosimilar CT-P13 Induction Therapy on Mucosal Healing in Ulcerative Colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:1273–1278. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jahnsen J. Clinical experience with infliximab biosimilar Remsima (CT-P13) in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9:322–329. doi: 10.1177/1756283X16636764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smits LJ, Derikx LA, de Jong DJ, Boshuizen RS, van Esch AA, Drenth JP, Hoentjen F. Clinical Outcomes Following a Switch from Remicade® to the Biosimilar CT-P13 in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:1287–1293. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sieczkowska J, Jarzębicka D, Banaszkiewicz A, Plocek A, Gawronska A, Toporowska-Kowalska E, Oracz G, Meglicka M, Kierkus J. Switching Between Infliximab Originator and Biosimilar in Paediatric Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Preliminary Observations. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:127–132. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smits LJT, Grelack A, Derikx LAAP, de Jong DJ, van Esch AAJ, Boshuizen RS, Drenth JPH, Hoentjen F. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes After Switching from Remicade® to Biosimilar CT-P13 in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:3117–3122. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4661-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonczi L, Gecse KB, Vegh Z, Kurti Z, Rutka M, Farkas K, Golovics PA, Lovasz BD, Banai J, Bene L, et al. Long-term Efficacy, Safety, and Immunogenicity of Biosimilar Infliximab After One Year in a Prospective Nationwide Cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1908–1915. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Argüelles-Arias F, Guerra Veloz MF, Perea Amarillo R, Vilches-Arenas A, Castro Laria L, Maldonado Pérez B, Chaaro Benallal D, Benítez Roldán A, Merino V, Ramirez G, et al. Switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: 12 months results. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:1290–1295. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guerra Veloz MF, Vázquez Morón JM, Belvis Jiménez M, Pallarés Manrique H, Valdés Delgado T, Castro Laria L, Maldonado Pérez B, Benítez Roldán A, Perea Amarillo R, Merino V, et al. Switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results of a multicenter study after 12 months. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2018;110:564–570. doi: 10.17235/reed.2018.5368/2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratnakumaran R, To N, Gracie DJ, Selinger CP, O'Connor A, Clark T, Carey N, Leigh K, Bourner L, Ford AC, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of initiating, or switching to, infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a large single-centre experience. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:700–707. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2018.1464203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jørgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL, Lorentzen M, Bolstad N, Haavardsholm EA, Lundin KEA, Mørk C, Jahnsen J, Kvien TK; NOR-SWITCH study group. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2304–2316. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ribaldone DG, Saracco GM, Astegiano M, Pellicano R. Efficacy of infliximab biosimilars in patients with Crohn's disease. Lancet. 2017;390:2435–2436. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danese S, Fiorino G, Raine T, Ferrante M, Kemp K, Kierkus J, Lakatos PL, Mantzaris G, van der Woude J, Panes J, et al. ECCO Position Statement on the Use of Biosimilars for Inflammatory Bowel Disease-An Update. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:26–34. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papamichael K, Gils A, Rutgeerts P, Levesque BG, Vermeire S, Sandborn WJ, Vande Casteele N. Role for therapeutic drug monitoring during induction therapy with TNF antagonists in IBD: evolution in the definition and management of primary nonresponse. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:182–197. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gisbert JP, Panés J. Loss of response and requirement of infliximab dose intensification in Crohn's disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:760–767. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rezk MF, Pieper B. To See or NOsee: The Debate on the Nocebo Effect and Optimizing the Use of Biosimilars. Adv Ther. 2018;35:749–753. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0719-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faasse K, Petrie KJ. The nocebo effect: patient expectations and medication side effects. Postgrad Med J. 2013;89:540–546. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jorgensen KK, Goll GL, Sexton I, Olsen IC. Long-term efficacy and safety of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) after switching from originator infliximab: Explorative subgroup analyses in IBD from the NOR-SWITCH EXTENSION trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2018:S348–S349. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strik AS, van de Vrie W, Bloemsaat-Minekus JPJ, Nurmohamed M, Bossuyt PJJ, Bodelier A, Rispens T, van Megen YJB, D'Haens GR; SECURE study group. Serum concentrations after switching from originator infliximab to the biosimilar CT-P13 in patients with quiescent inflammatory bowel disease (SECURE): an open-label, multicentre, phase 4 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:404–412. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiorino G, Manetti N, Armuzzi A, Orlando A, Variola A, Bonovas S, Bossa F, Maconi G, D’Incà R, Lionetti P, et al. The PROSIT-BIO Cohort: A Prospective Observational Study of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treated with Infliximab Biosimilar. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:233–243. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Komaki Y, Yamada A, Komaki F, Micic D, Ido A, Sakuraba A. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy and safety of CT-P13, a biosimilar of anti-tumour necrosis factor-α agent (infliximab), in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:1043–1057. doi: 10.1111/apt.13990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]