Abstract

Objectives

Three types of lichen planus (LP) occur on the vulva: erosive, classic, and hypertrophic. The latter 2 occur on keratinized skin and little is known about their clinicopathologic appearance.

Materials and Methods

Vulvar biopsies of keratinized skin reported as LP or “lichenoid” between 2011 and 2017 were reviewed. Inclusion required age of older than 18 years, a lichenoid tissue reaction, and insufficient abnormal dermal collagen to diagnose lichen sclerosus. Clinical and histopathologic data were collected and cases were categorized as hypertrophic, classic, or nonspecific lichenoid dermatosis. Descriptive statistics were performed and groups were compared with the Fisher exact test.

Results

Sixty-three cases met criteria for inclusion. Twenty-nine (46%) cases were categorized as hypertrophic LP, 21 (33%) as classic LP, and 13 (21%) as nonspecific lichenoid dermatosis. There were no significant differences in age, primary symptom, biopsy location, or duration of disease between the 3 groups. When compared with classic and nonspecific disease, hypertrophic LP was less likely to have comorbid dermatoses and more likely to be red, diffuse, have scale crust, and contain plasma cells in the infiltrate. Nonspecific disease had similar clinical features to classic LP but was less likely than the other 2 categories to have a dense lymphocytic infiltrate and exocytosis.

Conclusions

Vulvar LP on keratinized skin has a diversity of appearances and presents a clinicopathologic challenge. Further research is required to understand the natural history of hypertrophic LP and the underlying diagnosis of nonspecific lichenoid cases.

Key Words: vulva, hypertrophic lichen planus, classic lichen planus, nonspecific lichenoid, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia

Lichen planus (LP) is a T-cell mediated inflammatory dermatosis that affects both keratinized and nonkeratinized squamous epithelium.1 Three types are described on the vulva: erosive, classic, and hypertrophic.2,3 Previous research has focused on erosive LP, which usually occurs on nonkeratinized squamous epithelium of the vestibule and adjacent hairless skin of labia minora but may also extend into the vagina. It manifests as well-demarcated glazed erythema, often with a hyperkeratotic border. Histopathologic features of erosive LP include a thinned or eroded epithelium, evidence of basal layer degeneration or regeneration, and a closely applied band-like lymphocytic infiltrate.4,5

In contrast, LP on keratinized vulvar skin is infrequently discussed, and the histopathologic description is extrapolated from nongenital skin. Two cohort studies of vulvar LP that specified clinicopathologic subtype noted 6% to 29% cases were hypertrophic and 4% to 6% were classic.2,6 The textbook description of classic LP is pruritic papules and plaques of variable color that occur anywhere and spontaneously resolve. Hypertrophic LP is usually characterized as thick violaceous plaques on extensor surfaces of lower extremities; perianal skin is reported as a site of predilection but this is not well documented.3,7,8 Controversy continues regarding the association between LP and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with scant evidence for malignant transformation of both hypertrophic and erosive LP.9–12

This study aims to describe the clinical and histopathologic characteristics of LP on vulvar keratinized skin and categorize cases as classic or hypertrophic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Pathology New South Wales, Hunter New England database was searched for “lichen planus,” “lichenoid,” and “vulva” between 2011 and 2017. Reports were reviewed to select biopsies from hairless and/or hair-bearing skin interpreted as LP or lichenoid tissue reaction. All cases were from women older than 18 years. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) slides were reviewed. Immunohistochemistry for p16 and p53 was performed for standard indications—to assist in distinguishing between reactive change, dermatosis-associated neoplasia, and human papillomavirus (HPV)-dependent lesions. The Hunter New England Research Ethics and Governance Unit approved this retrospective histopathologic case series (HREC 15/11/18/5.02); signed written consent was obtained for use of clinical photographs.

Inclusion required histopathologic evidence of the lichenoid reaction: a closely applied band-like infiltrate along with basal layer degeneration seen as apoptotic bodies, vacuolar change, and/or squamatization.13 Specimens with multifocal or diffuse homogenized collagen in the papillary dermis were considered to demonstrate lichen sclerosus (LS) and were excluded.14 Findings of scant unifocal sclerosis or a thickened basement membrane were considered to be insufficient for diagnosis of LS. Cases were categorized as classic LP if a lichenoid reaction was accompanied by acanthosis seen as spiky, sawtooth, or irregular rete ridges.15

Hypertrophic LP was defined as a lichenoid reaction accompanied by parakeratosis or hypergranulosis and marked acanthosis; supportive findings included hyperkeratosis and papillary dermal fibrosis.13,15 Specimens lacking these distinguishing features were classified as nonspecific lichenoid reaction.7,16 Biopsies were inspected for pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH), which shows epithelial architecture resembling SCC with separated nests and tentacles protruding into the dermis, but lacks the nuclear atypia and inflamed desmoplastic reaction characteristic of neoplasia.7,17 Specimens were also reviewed for areas of verruciform morphology and premature maturation without sufficient basal layer atypia to meet criteria for differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN).18,19

Site was recorded as hair-bearing skin or hairless skin. Anatomic location was grouped into the following 3 zones: (1) mons and labium majus, (2) labium minus and periclitoris, and (3) perineum and perianus. The location of basal layer changes was labeled as diffuse, at tips of rete ridges, or at tops of papillary processes. Involvement of hair follicles and skin appendages by the lichenoid reaction was noted. Exocytosis and the dermal lymphocytic infiltrate were semiquantitatively assessed as sparse, moderate, or dense, and cell types were recorded. The PAS was inspected for presence of yeast or dermatophytes. Scale crust, dermal pigment incontinence, and focal collagen abnormalities were recorded as present or absent.

Clinical data obtained included provisional diagnosis, lesion appearance, previous treatments, symptoms and their duration, dermatologic and autoimmune comorbidities, microbiologic results, treatment and outcome, and duration of follow-up. Descriptive statistics were performed and group comparisons were made with the Fisher exact test.

RESULTS

After histopathologic review, 63 cases were included in the study. Twenty-nine (46%) cases were categorized as hypertrophic LP, 21 (33%) as classic LP, and 13 (21%) as nonspecific lichenoid reaction. There was no significant difference in age, clinician specialty, primary symptom, biopsy location, or duration of symptoms between the 3 categories (see Table 1). Nine cases had a systemic autoimmune disease identified: 4 (14%) in classic LP, 3 (10%) in hypertrophic LP, and 2 (15%) in nonspecific lichenoid. These included thyroid disease in 3, systemic lupus erythematosus in 2, and 1 each with Crohn disease, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, polymyalgia rheumatica, and an unclear autoimmune condition. Topical corticosteroids were prescribed before referral in 26 (41%) of cases with similar rates across the 3 disease types.

TABLE 1.

Clinical Features of Vulvar Lichen Planus on Keratinized Skin

Clinicians identified a provisional diagnosis of LP in less than half of cases, instead suspecting LS, lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, VIN, Hailey-Hailey disease (1), granulomatous lesions (1), and estrogen deficiency (1). Body mass index was documented in 24 (38%) of 63, with a mean of 31 (range = 22–40). Of 35 (55%) cases with microbiology, 27 (77%) had normal flora, 6 (17%) grew Candida albicans, and 6% showed nonalbicans species; a swab was not obtained in 24 (38%) of 63 cases, and data were unavailable in 4 (6%). Women with a positive swab for C. albicans ranged in age from 62 to 77 years, of whom 3 used vaginal estrogen, 1 was on systemic estrogen, 1 had diabetes mellitus, and 1 had no reported risk factors. Treatment information was available in 59 (94%) cases; 58 (98%) were prescribed potent topical corticosteroid ointment and 1 declined further care after treatment for vulvar cancer. Adjunctive medications included antimycotics (7, 13%), topical or systemic estrogen (5, 9%), antibiotics (4, 7%), oral prednisone (1, 2%), and topical tacrolimus (1). Lesion resolution was documented in 6 (11%) cases, of which 5 were classic LP and 1 was nonspecific lichenoid. Five (9%) women were lost to follow-up, 4 (7%) had suboptimal response or adherence to treatment, and the remainder were improved on chronic therapy with a mean follow-up of 24 months.

Biopsy site of hairless skin versus hair-bearing skin was not significantly different across the 3 categories of disease (see Table 2). No case had evidence of mycosis on PAS. Most specimens showed hyperkeratosis (78%), hypergranulosis (70%), irregular or spiky acanthosis (81%), and a moderate to dense band-like lymphocytic infiltrate (98%). Exocytosis was lymphocytic in all but 3 cases—1 also had plasma cells and 2 had eosinophils, with neutrophils in 1 of these. All but 5 (8%) cases showed more than 1 manifestation of basal layer degeneration; the abnormality was confined to either rete tips or tops of papillary processes in 17 (27%). Lymphocytes and histiocytes were the primary cell types in the dermal infiltrate. Three cases had a granulomatous component to the infiltrate—2 were hypertrophic LP and 1 was nonspecific lichenoid. There were no differences across the 3 categories with regard to papillary dermal fibrosis and scant focal sclerosis.

TABLE 2.

Histopathologic Characteristics of Vulvar Lichen Planus on Keratinized Skin

The most common description of classic LP was a well-circumscribed, unilateral, homogenous, slightly raised plaque (see Figure 1). Classic LP lesions were red, purple, brown, or grey-white and sometimes noted to be “subtle” or “unusual.” Comorbid dermatoses included psoriasis in 2, biopsy-proven LS in 2, orolabial LP in 2, classic LP of the eyelid in 1, scalp lichen planopilaris in 1, and vulvovaginal erosive LP in 1. Classic LP was more likely to demonstrate spiky acanthosis (13/21 [62%] vs 4/42 [10%], p = .0001) and wedge-shaped hypergranulosis (11/21 [52%] vs 8/42 [19%], p = .01) than the other 2 categories (see Figures 2, 3). Classic LP was the only type that involved the hair follicles and/or skin appendages (5/21 [24%] vs 0, p = .003) (see Figure 3). Two (10%) cases showed PEH, and there was no previous or concurrent VIN.

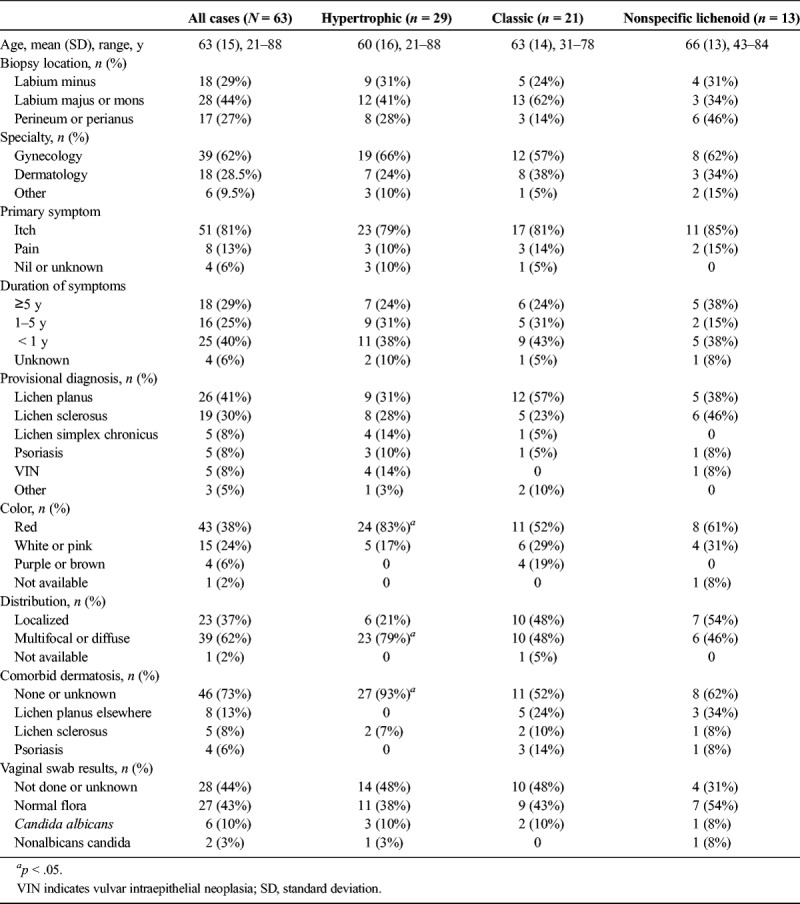

FIGURE 1.

Classic lichen planus: subtle brown-purple plaque on left labium majus (A), red plaque on right mons pubis (B), and grey-pink plaque on left labium majus (C).

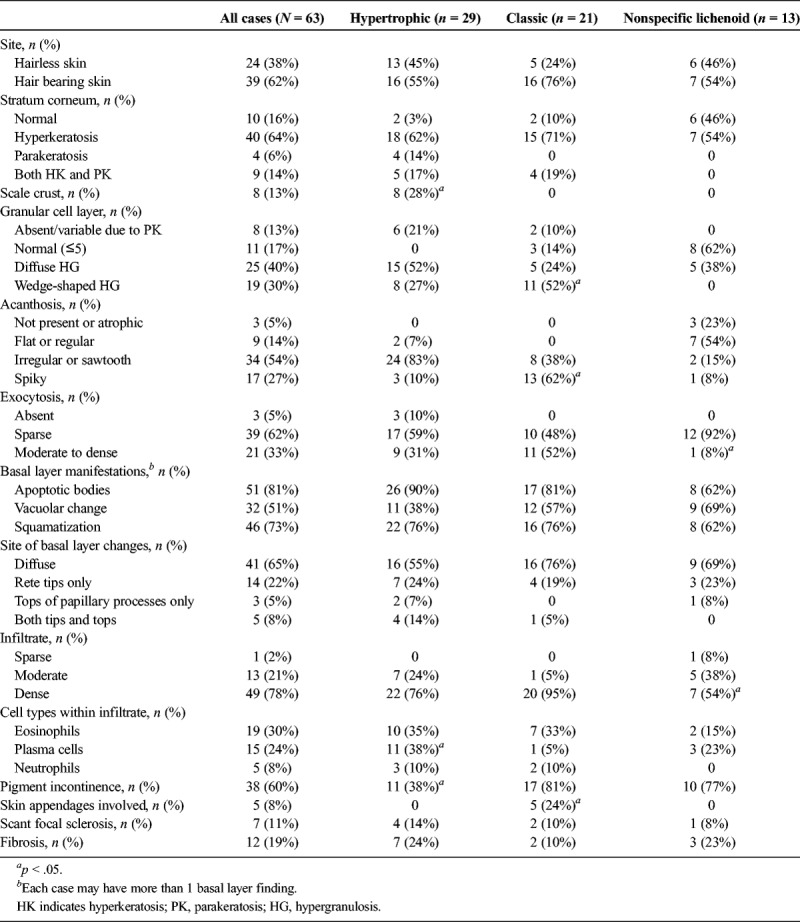

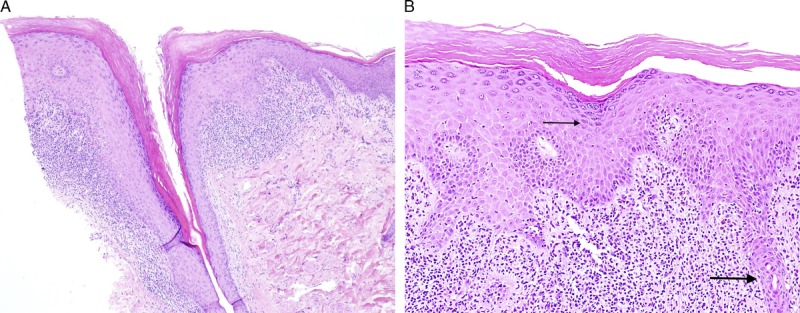

FIGURE 2.

Classic lichen planus: circumferential erythematous plaque most prominent on hair bearing skin of labia majora (A), parakeratosis spiky acanthosis, and moderate lymphocytic infiltrate (B), H&E ×100.

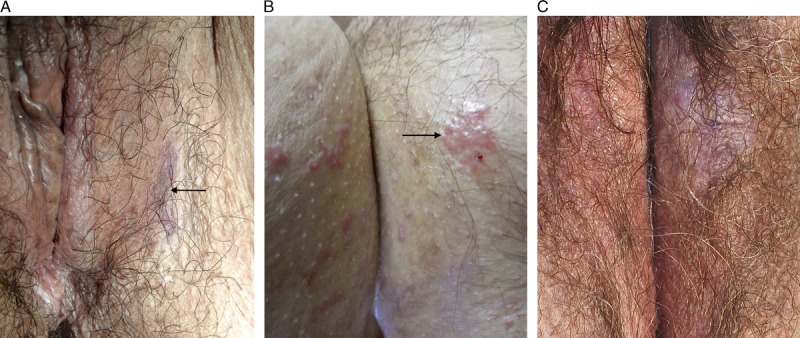

FIGURE 3.

Classic lichen planus with appendageal involvement: hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, irregular acanthosis, and dense lymphocytic infiltrate, with involvement of the hair follicle (A), H&E ×40, and wedge shaped hypergranulosis (thin arrow), spiky acanthosis, and involvement of the eccrine gland (thick arrow) (B), H&E ×100.

Clinical features of the nonspecific lichenoid category were similar to cases diagnosed as classic LP. No clinical photographs were available. Comorbid dermatoses included nongenital classic LP in 2, vulvar erosive LP in 1, and psoriasis in 1. One case was identified by perianal biopsy done concurrently with anterior vulvectomy for LS-associated SCC. A vulvar high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) occurred in 1 woman, confirmed by block positive p16. One case was managed with imiquimod and LASER ablation after a pathology report of “VIN2,” with subsequent clinicopathologic review demonstrating a lichenoid reaction and no evidence of HPV-dependent disease. The histopathologic features of nonspecific lichenoid reaction included hyperkeratosis (54%), a normal granular cell layer (62%), and flat or regular acanthosis (54%), although there was a spectrum of appearances (see Figure 4). Nonspecific lichenoid cases were less likely than classic and hypertrophic LP to have a dense lymphocytic infiltrate (7/13 [54%] vs 42/50 [84%], p = .03) and moderate to dense exocytosis (1/13 [8%] vs 20/50 [40%], p = .04). None had PEH.

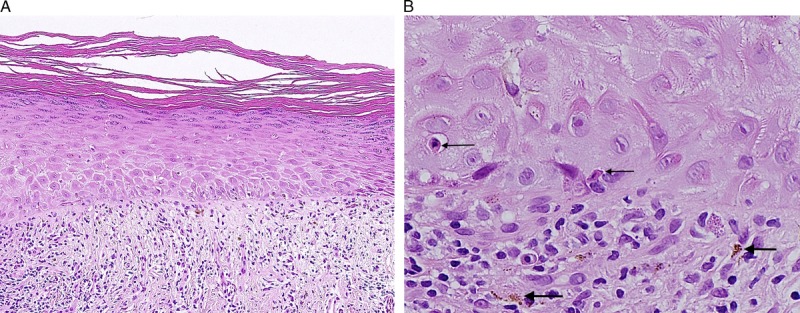

FIGURE 4.

Nonspecific lichenoid reaction: hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, flat acanthosis, thickened basement membrane, moderate lymphocytic infiltrate, and normal dermal collagen (A), H&E ×100 and dermoepidermal interface with apoptotic bodies (thin arrows) and pigment incontinence (thick arrows) (B), H&E ×400.

Hypertrophic LP was more likely to be described as a red (24/29 [83%] vs 19/34 [56%], p = .02), diffuse abnormality (23/29 [79%] vs 16/34 [47%], p = .01) when compared with classic and nonspecific disease and was less likely to have other dermatoses identified (27/29 [93%] vs 19/34 [56%], p = .001) (see Figure 5). The 2 comorbid diagnoses were both biopsy-proven LS adjacent to perineal/perianal LP. Clinical photographs demonstrate a pattern of circumferential erythema extending over labia minora and partially across labia majora, transitioning to lichenification laterally (see Figures 6, 7). Compared with classic LP and nonspecific lichenoid, hypertrophic LP more often had scale crust (8/29 [28%] vs 0, p = .001) and plasma cells in the infiltrate (11/29 [38%] vs 4/34 [12%], p = .02) and was less likely to show pigment incontinence (11/29 [38%] vs 27/34 [79%], p = .02). Four (14%) specimens showed PEH. Two cases contained a differentiated verruciform lesion: 1 had previous treatment of microinvasive SCC and several subsequent excisions of dVIN in a field of nonspecific lichenoid dermatosis, whereas the other had lesion resolution after treatment with corticosteroids and antimycotics. p53 was obtained in 2 cases to distinguish reactive versus atypical nuclear changes, and both were wild-type.

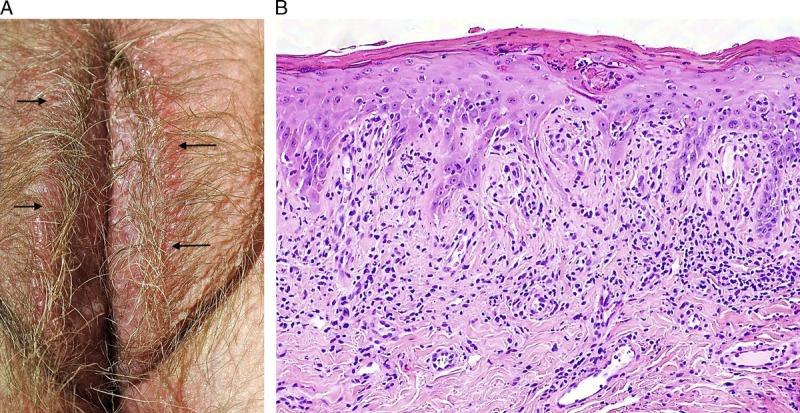

FIGURE 5.

Hypertrophic lichen planus: circumferential erythema and edema extending midway across the labia majora.

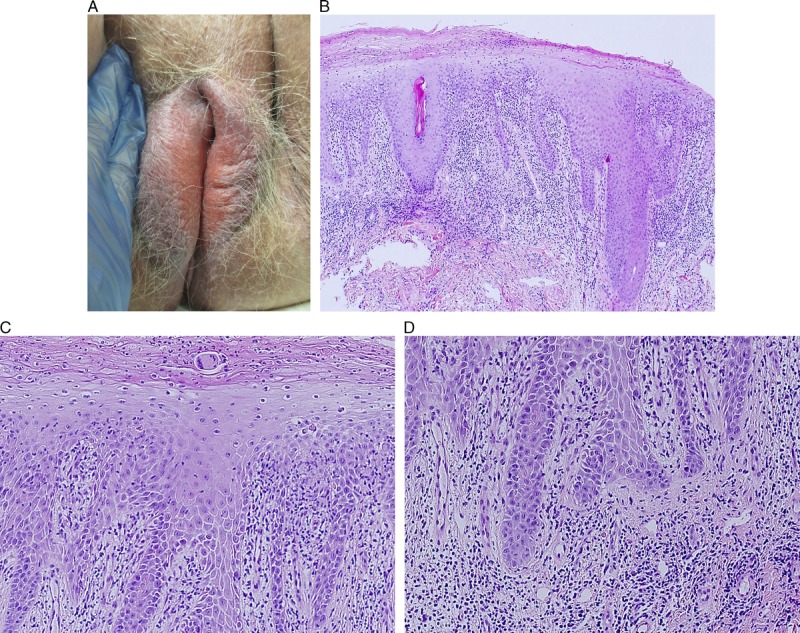

FIGURE 6.

Hypertrophic lichen planus: erythema and edema of inner vulva transitioning to grey-pink lichenification of bilateral labia majora (A), scale crust accompanied by marked irregular acanthosis and dense infiltrate (B), H&E ×40, apoptotic bodies and squamatization predominantly involving the tops of papillary processes (C), H&E ×100, with minimal basilar abnormality at the tips of rete ridges (D), H&E ×100.

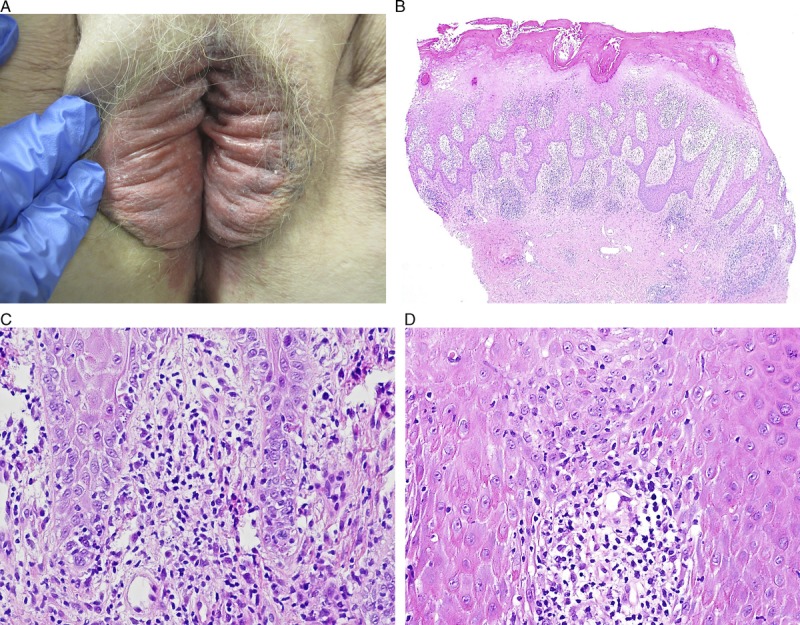

FIGURE 7.

Hypertrophic lichen planus: dusky erythema, edema, and a macerated appearance of inner vulva, transitioning to grey-pink lichenification of bilateral labia majora (A), scale crust with parakeratosis, marked irregular acanthosis, and dense infiltrate (B), H&E ×40, with basal layer degeneration at the rete tips (C), H&E ×200, and tops of papillary processes (D), H&E ×200.

DISCUSSION

Lichen planus on vulvar keratinized skin has a diversity of appearances and presents a diagnostic challenge to both clinicians and pathologists. Hypertrophic LP has the most dramatic clinical presentation and is the least described in the literature, perhaps accounting for low rates of accurate provisional diagnosis. Although its circumferential distribution is similar to LS, hypertrophic LP lacks porcelain-white pallor, and instead demonstrates beefy erythema and edema of inner vulva, often with a macerated or rind-like surface and transition to lichenification laterally.3,20 Thick red plaques lead to confusion with psoriasis, extramammary Paget disease, and HSIL, although the latter 2 usually display an asymmetric distribution and distinct histopathologic features. However, hypertrophic LP, nodular prurigo, and lichenified psoriasis represent a difficult differential diagnosis, because all demonstrate papillary dermal fibrosis and marked acanthosis. Among these 3, the sole factor that distinguishes hypertrophic LP is basal layer degeneration, which may be masked or mimicked by inflammation relating to superinfection. This study identifies that basal layer degeneration may be diffuse or confined to tops of papillary processes, in contrast to the textbook description of damage restricted to tips of rete ridges.13 Thus, both “tips” and “tops” must be carefully inspected for vacuolar change, squamatization, and apoptotic bodies, with the latter being most useful when attempting to distinguish between marked exocytosis and true basal layer damage. In addition, PEH may be confused for microinvasive SCC and granulomatous infiltrates may be misinterpreted as systemic autoimmune or infectious diseases.21

Classic LP is a more straightforward clinicopathologic diagnosis, although the range of colors and patterns may be unfamiliar to nondermatologists.20 A few cases have a normal stratum corneum and/or granular cell layer, so diagnosis relies on rete ridge abnormalities in combination with the lichenoid reaction. The 24% rate of resolution may be an underestimate related to duration of follow-up or misidentification of postinflammatory pigmentation as ongoing disease or could reflect a different natural history of vulvar versus nongenital disease.

A fifth of biopsies did not meet criteria for diagnosis of either hypertrophic or classic LP. It is unclear whether these nonspecific lichenoid cases are part of the spectrum of vulvar LP or whether they primarily represent LS in a nonsclerotic or minimally fibrotic phase.14,22 Nonspecific lichenoid cases had fewer lymphocytes in both dermis and epidermis, perhaps indicating less severe inflammation. This cannot be explained by duration of disease or previous treatment, because these were similar across disease categories. Although not a statistically significant difference, the rate of perianal/perineal biopsies was highest in nonspecific lichenoid reaction; biopsies performed elsewhere might display more identifiable histopathologic features.16

Assessment of all 3 categories of nonerosive vulvar LP is complicated by high rates of comorbid dermatologic and infectious disease. All lichenoid dermatoses are associated with each other: however, each diagnosis and site have different management strategies and associated risks of neoplasia.4,8,10,12,23,24 Thus, it is important to obtain the most accurate diagnoses across all locations, which often requires biopsies of morphologically distinct areas and thoughtful clinicopathologic correlation. Psoriasis was identified in 14% of classic LP cases, more than the 5% documented in a retrospective cohort of erosive LP.25 The true prevalence of candidal superinfection of LP is unknown. Retrospective cohorts of LP have documented rates from 4% to 25%, but most studies make no comment on surveillance for mycosis.4,26,27 Likewise, it is unclear whether rates of candidosis relate to topical corticosteroids, exogenous estrogen, or medical conditions associated with lichenoid dermatoses.27–29 These questions would best be addressed prospectively with a systematic approach to detection and detailed notation of medication exposures and risk factors.

There were 3 cases of vulvar neoplasia in this cohort: 1 case of HSIL (usual VIN), 1 of LS-associated SCC with a noncontiguous lichenoid reaction, and 1 with previous SCC and recurrent dVIN. Perilesional histopathology of the latter showed nonspecific lichenoid on 3 occasions and was diagnostic for hypertrophic LP once. Clinical photographs were consistent with hypertrophic LP, yet the long-standing clinical diagnosis was LS and biopsy was not obtained until concern for neoplasia arose. These 3 examples highlight the challenges in establishing the neoplastic risk of vulvar LP: LS and hypertrophic LP may be difficult to distinguish clinically, multiple diagnoses may coexist and be adjacent or noncontiguous, and some forms of HSIL and dVIN have a similar histopathologic appearance.5,10,30 Differentiated verruciform lesions occurred in 2 cases of hypertrophic LP; these may be precursors to dVIN, may represent a distinct pathway to HPV-independent vulvar SCC, or may be an exaggerated but reversible response to inflammation and the itch-scratch cycle.10,18

Inherent to the retrospective design, limitations of this study include incomplete data, variations in individual practice patterns, and a bias toward unusual or difficult cases more likely selected for vulvar biopsy. Clinicians in obesity-endemic areas may be more likely to document body mass index than those in other settings. Nonperformance of microbiologic studies may be due either to well-informed low suspicion for mycosis or a lack of awareness of superinfection in chronic vulvar dermatoses. Universal clinical photography would allow for better representation of the patterns of each disease type and determination of best-fit diagnoses for nonspecific lichenoid reactions.

In summary, vulvar hypertrophic LP usually has a dramatic presentation of circumferential erythematous plaques seen on microscopy as a pronounced inflammatory band against markedly lichenified epithelium, whereas classic LP has a spectrum of lesion color and morphology seen as a lichenoid reaction with spiky or irregular acanthosis. Perhaps because of the unique vulvar milleu, both diseases may lack the pathognomonic findings of their nongenital counterparts. Research with a focus on clinicopathologic correlation is required to elucidate the underlying diagnosis of nonspecific lichenoid cases and to better describe the natural history and neoplastic potential of hypertrophic LP.

Footnotes

T.D. is supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

The authors have declared they have no conflicts of interest.

This study was approved by Hunter New England Research Ethics and Governance Unit (HREC 15/11/18/5.02)

REFERENCES

- 1.Terlou A, Santegoets LA, van der Meijen WI, et al. An autoimmune phenotype in vulvar lichen sclerosus and lichen planus: a Th 1 response and high levels of microRNA-155. J Invest Dermatol 2012;132:58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chew A, Stefanato C, Savarese I, et al. Clinical patterns of lichen planopilaris in patients with vulval lichen planus. Br J Dermatol 2014;170:218–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein A, Metz A. Vulvar lichen planus. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2005;48:818–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Day T, Moore S, Bohl TG, et al. Cormorbid vulvar lichen planus and lichen sclerosus. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2017;21:204–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Day T, Bowden N, Jaaback K, et al. Distinguishing erosive lichen planus from differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2016;20:174–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belfiore P, Di Fede O, Cabibi D, et al. Prevalence of vulval lichen planus in a cohort of women with oral lichen planus: an interdisciplinary study. Br J Dermatol 2006;155:994–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day T, Bohl TG, Scurry J. Perianal lichen dermatoses: a review of 60 cases. Australas J Dermatol 2016;57:210–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McPherson T, Cooper S. Vulval lichen sclerosus and planus. Dermatol Ther 2010;23:523–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regauer S, Reich O, Eberz B. Vulvar cancers in women with vulvar lichen planus: a clinicopathological study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;71:698–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Day T, Otton G, Jaaback K, et al. Is vulvovaginal lichen planus associated with squamous cell carcinoma? J Low Genit Tract Dis 2018;22:159–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramos-e-Silva M, Jacques C, Carneiro SC. Premalignant nature of oral and vulval lichen planus: facts and controversies. Clin Dermtol 2010;28:563–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson RC, Murphy R. Is vulval erosive lichen planus a premalignant condition? Arch Dermatol 2012;148:1314–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Tissue reaction patterns, Section 2, and The dermis and subcutis, Section 4. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon's Skin Pathology 4th ed London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016;37–80, 362–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weyers W. Hypertrophic lichen sclerosus sine sclerosis: clues to histopathologic diagnosis when presenting with psoriasiform lichenoid dermatitis. J Cutan Pathol 2015;42:118–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang W, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis, Chapter 7. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al., eds. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed London: Elsevier; 2012:219–58. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Day T, Knight V, Dyall-Smith D, et al. Interpretation of non-diagnostic vulvar viopsies. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2018;22:74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee ES, Allen D, Scurry J. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in lichen sclerosus of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2003;22:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watkins JC, Howitt BE, Horowitz NS, et al. Differentiated exophytic vulvar intraepithelial lesions are genetically distinct from keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas and contain mutations in PIK3CA. Mod Path 2017;30:448–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nascimento AF, Granter SR, Cviko A, et al. Vulvar acanthosis with altered differentiation: a precursor to verrucous carcinioma? Am J Surg Path 2004;28:638–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moyal-Barracco M, Edwards L. Diagnosis and therapy of anogenital lichen planus. Dermatol Ther 2004;17:38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashton KA, Scurry J, Rutherford J, et al. Nodular prurigo of the vulva. Pathology 2010;44:565–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scurry J, Whitehead J, Healey M. Histology of lichen sclerosus varies according to site and proximity to carcinoma. Am J Dermatopath 2001;23:413–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis FM, Tatnell FM, Velangi SS, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guideline for the management of lichen sclerosus, 2018. Br J Dermatol 2018;178:839–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper SM, Wojnarowska F. Influence of treatment of erosive lichen planus of the vulva on its prognosis. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirtschig G, Wakelin SH, Wojnarowska F. Mucosal vulval lichen planus: outcome, clinical and laboratory features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2005;19:301–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradford J, Fischer G. Management of vulvovaginal lichen planus: a new approach. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2013;17:28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Day T, Borbolla Foster A, Phillips S, et al. Can routine histopathology distinguish between vulvar cutaneous candidosis and dermatophytosis? J Low Genit Tract Dis 2016;20:174–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Virgili A, Borghi A, Cazzaniga S, et al. New insights into potential risk factors and associations in genital lichen sclerosus: data from a multicenter Italian study on 729 consecutive cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31:699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of vulval lichen sclerosus in adult women. Aust NZ. J Obstet Gynaecol 2010;50:148–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ordi J, Alejo M, Fusté V, et al. HPV-negative vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) with basaloid histologic pattern: an unrecognized variant of simplex (differentiated) VIN. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1659–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]