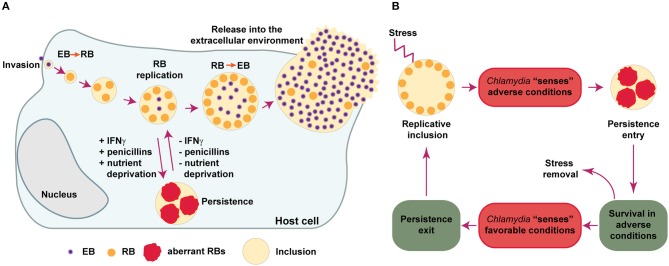

Figure 1.

Chlamydia developmental cycle. (A) Chlamydia are obligate intracellular bacteria that undergo multiple developmental forms with distinct morphological and functional properties. The infectious elementary bodies (EB) are internalized in the host cells and are confined to a membrane-bound vacuole, termed an “inclusion.” Soon after invasion, EBs differentiate into replicative but non-infectious reticulate bodies (RBs), which actively divide. Around mid-cycle, RBs begin to asynchronously differentiate back into EBs and are finally released (by cell lysis or extrusion of intact inclusions) into the extracellular environment, where they can infect neighboring cells. If during replication Chlamydia is exposed to stressing conditions, like those caused by gamma-interferon (IFNγ), penicillins or deprivation of essential nutrients, the bacteria enter into a long-lasting, viable but non-cultivable state known as “Chlamydia persistence,” which is typically associated to the presence of enlarged, aberrant RBs. When conditions are again favorable, the persistence state is reversed and normal replication ensues. (B) This scheme summarizes different events that Chlamydia may use in order to successfully evade antimicrobial effects triggered during infection in-vitro. First, Chlamydia “senses” different types of stresses and then respond by entering into a temporary, reversible interruption in the replication cycle (termed “Chlamydia persistence” or “Chlamydia stress response”). In this state, Chlamydia adapts to adverse conditions by prioritizing cell functions required for long-lasting survival. When the bacteria sense that the stressing condition has ceased, they exit from persistence and resume normal replication and generation of infectious progeny. The Chlamydia factors and the molecular mechanisms required for the successful execution of each one of these steps remain poorly elucidated.