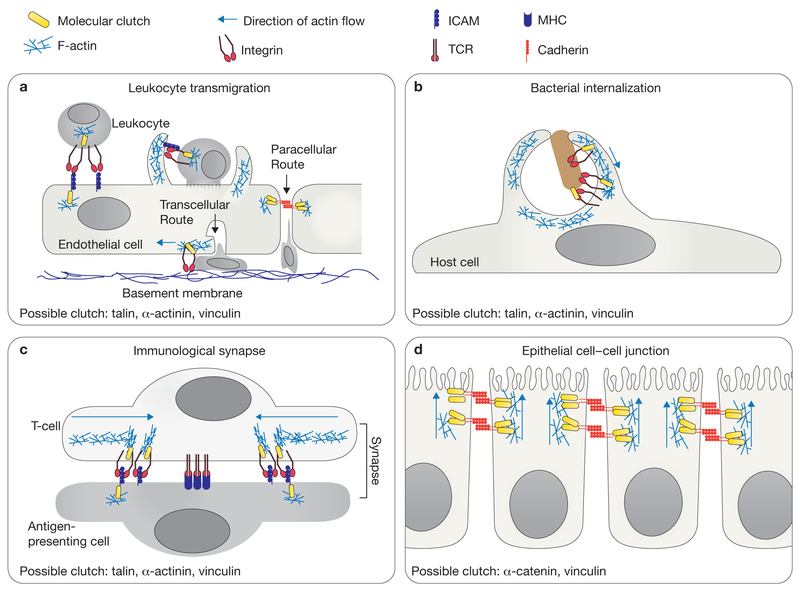

Figure 3.

Molecular clutches may mediate diverse cell adhesive interactions. (a) During leukocyte diapedesis, initial cell–cell adhesion is mediated by the interactions of the LFA−1 integrin and its ligand ICAM−1. Paracellular migration occurs when the endothelial cells temporarily disassemble cell–cell junctions, allowing the leukocyte to migrate between two endothelial cells. Transcellular migration occurs when the leukocyte migrates through a single endothelial cell. The migrating leukocyte extends invasive protrusions into the endothelial cell, and the endothelial cell forms a transmigratory cup around the leukocyte. Following successful transmigration, the transmigratory pore is closed by integrin-dependent ventral lamellipodia to restore endothelial barrier integrity. (b) Pathogens often seek entry into host cells by co-opting the integrin or cadherin adhesion machinery. Bacteria can bind to these adhesion receptors, stimulate actin polymerization and activate clutch molecules to promote the formation of a phagocytic cup. (c) The T-cell immunological synapse requires centripetal actin flow to organize adhesion receptors into distinct domains. Rapid retrograde flow organizes and potentially activates LFA−1 integrins in the actin-rich regions. In contrast, the T-cell receptors (TCR) cluster in the actin-free centre. MHC, major histocompatibility complex. (d) Cadherins mediate cell–cell adhesion and connect indirectly to the actin cytoskeleton through β-catenin, α-catenin and vinculin. Cadherins have been observed to undergo actin-dependent basal-to-apical flow that could generate force for epithelial morphogenesis. Active polymerization of the actin cytoskeleton is depicted as a blue mesh and the direction of actin flow is indicated with a blue arrow (a–d).