Abstract

Background

In recent years, research has consistently proven the occurrence of genetic overlap across autoimmune diseases, which supports the existence of common pathogenic mechanisms in autoimmunity. The objective of this study was to further investigate this shared genetic component.

Methods

For this purpose, we performed a cross-disease meta-analysis of Immunochip data from 37,159 patients diagnosed with a seropositive autoimmune disease (11,489 celiac disease (CeD), 15,523 rheumatoid arthritis (RA), 3477 systemic sclerosis (SSc), and 6670 type 1 diabetes (T1D)) and 22,308 healthy controls of European origin using the R package ASSET.

Results

We identified 38 risk variants shared by at least two of the conditions analyzed, five of which represent new pleiotropic loci in autoimmunity. We also identified six novel genome-wide associations for the diseases studied. Cell-specific functional annotations and biological pathway enrichment analyses suggested that pleiotropic variants may act by deregulating gene expression in different subsets of T cells, especially Th17 and regulatory T cells. Finally, drug repositioning analysis evidenced several drugs that could represent promising candidates for CeD, RA, SSc, and T1D treatment.

Conclusions

In this study, we have been able to advance in the knowledge of the genetic overlap existing in autoimmunity, thus shedding light on common molecular mechanisms of disease and suggesting novel drug targets that could be explored for the treatment of the autoimmune diseases studied.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13073-018-0604-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Celiac disease; Rheumatoid arthritis; Systemic sclerosis; Type 1 diabetes; Cross-disease meta-analysis, Immunochip; Autoimmune disease, functional enrichment analysis

Background

Autoimmune diseases present a complex etiology resulting from the interaction between both genetics and environmental factors. Although these conditions differ in their clinical manifestations, the existence of familial clustering across them as well as the co-occurrence of multiple immune-mediated disorders in the same individual points to the existence of a common genetic background in autoimmunity [1].

As a matter of fact, genomic studies have revealed that many genetic loci are associated with multiple immune-mediated phenotypes, thus suggesting that autoimmune disorders are likely to share molecular mechanisms of disease pathogenesis [2, 3]. In the last years, several approaches have been conducted to comprehensively explore this genetic overlap. In this regard, combined analysis of GWAS (genome-wide association study) or Immunochip data across multiple diseases simultaneously has emerged as a powerful strategy to identify novel pleiotropic risk loci as well as common pathogenic mechanisms in autoimmunity [4, 5]. Recently, a cross-phenotype study combining Immunochip data from five seronegative autoimmune diseases, including ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease (CD), psoriasis, primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis, identified numerous multidisease signals, some of which represented new pleiotropic risk loci in autoimmunity [4].

Considering the above, we decided to perform a similar approach by exploring genetic overlap across four seropositive autoimmune diseases. Specifically, Immunochip data from 37,159 patients with celiac disease (CeD), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic sclerosis (SSc) and type 1 diabetes (T1D) and 22,308 unaffected individuals were combined in a cross-disease meta-analysis. The aims of this study were (i) to identify new susceptibility loci shared by subsets of these four immune-related conditions, (ii) to identify new associations for individual diseases, and (iii) to shed light into the molecular mechanisms shared among these four disorders by integrating genotype and functional annotation data.

Methods

Study population

All samples were genotyped using Immunochip (Illumina, Inc., CA), a custom array designed for dense genotyping of 186 established genome-wide significant loci. The cohorts included in the present study are described in Additional file 1: Table S1. The CeD cohort, composed of 11,489 cases from Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and the UK, and the RA cohort, which included 13,819 cases from Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden, the UK, and the USA, came from a previous published meta-Immunochip [6]. In addition, 1788 RA samples from Spain (which did not overlap with the Spanish RA cases included in the Immunochip mentioned) were also analyzed. These patients were recruited in three different Spanish hospitals (Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid and Hospital La Princesa, Madrid) and were diagnosed with RA according to the 1987 classification criteria of the American College of Rheumatology [7]. The T1D set consisted of 6670 cases from the UK and has been described in a previous Immunochip study [8]. Finally, the SSc cohort, which consisted of 3597 cases from Spain, the USA, the UK, Italy, and the Netherlands, was also described in a previous Immunochip study [9].

Additionally, 22,365 ethnically matched control individuals were analyzed. As indicated in Additional file 1: Table S1, some of the control sets, specifically those from Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and the UK, overlapped among different diseases, which was taken into account for the subsequent cross-disease meta-analysis.

Quality control and imputation

Before imputation, data quality control was performed separately for each cohort using PLINK 1.9 [10]. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with low call rates (< 98%), low minor allele frequency (MAF < 0.01) and those that were not in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE; p < 0.001) were excluded. Individuals with successful call rates lower than 95% were also removed. Additionally, an individual of each pair of duplicates and first-degree relatives identified via the Genome function in PLINK 1.9 (PI-HAT > 0.4) was randomly discarded.

IMPUTE V.2 was used to perform SNP genotype imputation [11] using the 1000 Genomes Phase III as reference panel [12]. To maximize the quality of imputed SNPs, a probability threshold for merging genotypes of 0.9 was established. Imputation accuracy, measured as the correlation between imputed and true genotypes, considering the best-guess imputed genotypes (> 0.9 probability) was higher than 99% for all the analyzed cohorts. Imputed data were subsequently subjected to stringent quality filters in PLINK 1.9. Again, we filtered out SNPs with low call rates (< 98%) and low MAF (< 0.01) and those that deviated from HWE (p < 0.001). Moreover, after merging case/control sets, singleton SNPs and those showing strong evidence of discordance in genotype distribution between cases and controls due to possible miscalling were removed using an in-house Perl script.

To account for spurious associations resulting from ancestry differences among individuals, principal component (PC) analyses were performed in PLINK 1.9 and the gcta64 and R-base under GNU Public license V.2. We calculated the 10 first PCs using the markers informative of ancestry included in the Immunochip. Subjects showing more than four SDs from cluster centroids were excluded as outliers.

After applying quality control filters and genome imputation, we analyzed 252,970 polymorphisms in 37,159 autoimmune-disease patients (11,489 CeD, 15,523 RA, 3477 SSc, and 6670 T1D) and 22,308 healthy controls.

Statistical analysis

Disease-specific analysis

First, we performed association analyses within each specific disease. For this, each case/control set was analyzed by logistic regression on the best-guess genotypes (> 0.9 probability) including the first ten PCs as covariates in PLINK 1.9. Then, for CeD, RA, and SSc, for which several independent case/control sets were available, we combined the different cohorts (Additional file 1: Table S1) using inverse variance weighted meta-analysis in METASOFT [13]. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region (Chr6: 20–40 MB) and sex chromosomes were excluded. Genomic inflation factor lambda (λ) was calculated using 3120 SNPs included in the Immunochip that map to non-immune regions. In addition, to account for inflation due to sample size [14], we calculated λ1000, the inflation factor for an equivalent study of 1000 cases and 1000 controls. Quantile–quantile plots for the p values of each individual disease are shown in Additional file 2: Figure S1a-d.

Cross-disease meta-analysis

Subsequently, summary level data obtained from the association studies of each specific disease were used to identify pleiotropic SNPs (shared by at least two of the autoimmune diseases analyzed). For this purpose, we performed a subset-based meta-analysis applying the “h traits” function as implemented in ASSET [15]. ASSET is an R statistical software package specifically designed for detecting association signals across multiple studies. This method does not only return a p value, but it also shows the best subset containing the studies contributing to the overall association signal. Moreover, this method allows for accounting for shared subjects across distinct studies using case/control overlap matrices. Since some of the control sets included in the disease-specific association analyses were shared among different diseases, we used correlation matrices to adjust for the overlapping of control individuals. Quantile–quantile plot for the p values from the cross-disease meta-analysis is shown in Additional file 2: Figure S1e.

After subset-based meta-analysis, SNPs for which two-tailed p values were lower than 5 × 10− 8 were considered statistically significant. Genetic variants showing effects in opposite directions across diseases were considered as significant when p values for both positively and negatively associated subsets reached at least nominal significance (p < 0.05). For regions where several SNPs reached genome-wide significance, we considered as lead variants those for which the best subset included a higher number of diseases. Subsequently, in order to identify independent signals, we linkage disequilibrium (LD)-clumped the results of the subset-based meta-analysis using PLINK to select polymorphisms with r2 < 0.05 within 500-kb windows and at genome-wide significant level.

Confirmation of pleiotropic effects identified by ASSET

To assess the reliability of our findings, ASSET results were compared with those obtained using an alternative approach, the compare and contrast meta-analysis (CCMA) [16]. For pleiotropic variants identified using ASSET, we calculated z-scores for each disease-specific association analysis as well as for all the possible combinations of diseases, assuming an agonistic or an antagonistic effect of the variants. For each locus, the subset showing the largest z-score was considered as the best model. p values for the maximum z-scores were derived using an empirical null distribution by simulating 300,000,000 realizations of four normally distributed random variables (p value < 1.00E−08 for z-score ≥ 6.45) (Additional file 2: Figure S2) [16].

Identification of novel genome-wide associations

We investigated whether pleiotropic SNPs were associated at genome-wide significance level with any of the diseases included in the best subset. To such purpose, we checked the results for these variants in each disease-specific association analysis. Additionally, in the case of SNPs associated with a specific disease, the statistical power of the subset-based analysis is lower than that of standard meta-analysis, as a result of a multiple-testing penalty associated with comprehensive subset searches. Consequently, the SNPs showing p values < 5 × 10− 6 in the subset-based meta-analysis were also tested for association in each specific disease.

Gene prioritization

To identify the most likely causal genes at associated loci, independent signals were annotated using several databases. First, all associated genetic variants were annotated using the variant effect predictor (VEP) [17]. Then, we used Immunobase [18] and the GWAS catalog [19] to explore whether the lead SNPs—or variants in LD with them (r2 ≥ 0.2) according to the European population of the 1000 Genomes Project—had been previously associated with immune-mediated diseases at genome-wide significance level. For SNPs for which clear candidate genes have already been reported, we considered these as the most probable genes. On the other hand, in the case of SNPs for which clear candidate genes have not been reported, we took into account VEP annotations, as follows: for SNPs annotated as coding, we reported the gene where each particular variant mapped; for SNPs annotated as intronic, upstream, downstream, or intergenic, we prioritized genes by using DEPICT (Data-driven Expression-Prioritized Integration for Complex Traits). DEPICT is an integrative tool that employs predicted gene functions to systematically prioritize the most likely causal genes at associated loci [20].

Functional annotation and enrichment analysis

Functional annotation of lead polymorphisms and their correlated variants (r2 ≥ 0.8) was performed using publicly available functional and biological databases. On the one hand, the possible functional impact of non-synonymous SNPs was evaluated using SIFT [21]. On the other hand, Haploreg v4.1 [22] was used to explore whether SNPs overlapped with conserved positions (Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling: GERP), tissue-specific chromatin state methylation marks (promoter and enhancer marks) based on the core-HMM 15 state model, tissue-specific DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHSs), tissue-specific transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs), and/or published expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) signals in immune cell lines, cell types relevant for each specific disorder, and/or whole blood. Sources of Haploreg v4.1 include public datasets from the Roadmap Epigenomics project, the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) Consortium and more than 10 eQTL studies, including the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project.

Additionally, we used the GenomeRunner web server [23] to determine whether the set of pleiotropic SNPs significantly co-localized with regulatory genome annotation data in specific cell types from the ENCODE and Roadmap Epigenomics projects. Briefly, GenomeRunner calculates enrichment p values using Chi-squared test by evaluating whether a set of SNPs of interest co-localizes with regulatory datasets more often that could happen by chance. Specifically, we tested for overrepresentation of 161 TFBSs from the ENCODE project and histone modifications (acetylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27ac), mono-methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me1), and tri-methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me3)) and DHSs in 127 cell types from the Roadmap Epigenomics project. Regulatory enrichment p values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) procedure.

Identification of common molecular mechanisms

Next, we performed protein-protein interaction (PPI) and pathway analysis to evaluate the existence of biological processes enriched among the set of pleiotropic loci. PPI analysis was conducted using STRING 10.5 [24], a database of direct (physical) and indirect (functional) interactions derived from five main sources: genomic context prediction, high-throughput lab experiments, co-expression, text mining, and previous knowledge in databases. In STRING, each PPI is annotated with a score, ranging from 0 to 1, which indicates the confidence of the interaction. We also used the list of common genes to perform KEGG pathway analysis using WebGestalt (WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit) [25] with the human genome as reference set, the Benjamini Hochberg adjustment for multiple testing, and a minimum number of two genes per category.

Drug repurposing analysis

Finally, we investigated whether drugs currently used for other indications could be used for the treatment of RA, CeD, T1D, and/or SSc by using DrugBank (version 5.0.9, released 2017-10-02). DrugBank is a database containing 10,507 drug entries as well as 4772 non-redundant protein sequences linked to these drugs [26]. First, we identified genes in direct PPI with the pleiotropic genes by using STRING 10.5 [24], with a minimum required interaction score of 0.700 (high confidence) and excluding “text mining” as a source of interaction prediction. Subsequently, we searched DrugBank to identify pleiotropic genes, and genes in direct PPI with them, which are targets for approved, clinical trial or experimental pharmacologically active drugs.

Results

Cross-disease meta-analysis

After applying quality control filters and imputation, we analyzed Immunochip data from 37,159 patients diagnosed with an autoimmune disease (11,489 CeD, 15,523 RA, 3477 SSc, and 6670 T1D) and 22,308 healthy controls, all of them of European origin. We performed a subset-based association analysis using ASSET [15] to identify SNPs shared by at least two of the autoimmune conditions analyzed as well as the best subset of diseases contributing to the association signal. Summary statistics from the subset-based meta-analysis are available in Additional file 3. We observed 60 loci containing at least one genetic variant at genome-wide significance (p value ≤5 × 10− 08) in the meta-analysis (Additional file 2: Figure S3). After LD clumping, an independent association was found for 69 genetic variants within those genomic regions, 31 of which were associated with individual diseases and 38 were shared by two or more phenotypes (Additional file 1: Table S2).

The 38 identified common variants mapped on 34 different genomic regions (Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S2). According to the GWAS Catalog and Immunobase [18, 19], five of these shared loci (PADI4 at 1p36.13, NAB1 at 2q32.3, COBL at 7p12.1, CCL21 at 9p13.3, and GATA3 at 10p14) have been associated with a single autoimmune disease so far and thus they represent new pleiotropic loci in autoimmunity. We also observed several independent signals within three known shared risk loci, four of which (rs1217403 in PTPN22, rs6749371 and rs7574865 in STAT4, and rs17753641 in IL12A) are new signals for some of the diseases contributing to the association (Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S2). For example, we identified two independent variants associated with RA and T1D in PTPN22: rs2476601—a known risk variant for both conditions—and rs1217403—which is not linked to the SNPs previously associated with RA and T1D (r2 = 0.03). Interestingly, three independent multi-disease signals were detected within the 2q32.3 region, two of them (rs6749371 and rs7574865) located within STAT4 and another one (rs10931468) located within the NAB1 gene (Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S2). Interestingly, this last locus has not been previously associated with any of the diseases contributing to the association signal, RA, and SSc.

Table 1.

Independent genetic variants reaching genome-wide level of significance in the subset-based meta-analysis and showing pleiotropic effects across diseases

| Region | Position (bp) | SNP | Gene | A1 | P2sided | Best subset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p36.32 | 2,534,978 | rs6664969 | MMEL1 | A | 2.86E−10 | CeD RA |

| 1p36.13 | 17,655,407 | rs1748041 | PADI4 | C | 3.63E−08 | RA SSc |

| 1p13.2 | 114,377,568 | rs2476601 | PTPN22 | A | 6.36E−119 | RA T1D |

| 1p13.2 | 114,388,804 | rs1217403 | PTPN22 | C | 4.66E−11 | RA* T1D* |

| 1q24.3 | 172,674,776 | rs10912267 | FASLG | A | 3.90E−09 | CeD T1D |

| 2q11.2 | 100,764,004 | rs13415465 | AFF3 | G | 3.72E−12 | CeD RA T1D |

| 2q31.3 | 182,057,640 | rs12619531 | ITGA4 | G | 1.18E−18 | CeD SSc |

| 2q32.3 | 191,538,562 | rs10931468 | NAB1 | A | 1.56E−08 | RA SSc |

| 2q32.3 | 191,902,184 | rs6749371 | STAT4 | T | 3.84E−08 | CeD SSc* |

| 2q32.3 | 191,964,633 | rs7574865 | STAT4 | T | 3.16E−09 | CeD* RA SSc T1D* |

| 2q33.2 | 204,612,058 | rs7426056 | CD28 | A | 6.68E−12 | CeD RA |

| 2q33.2 | 204,738,919 | rs3087243 | CTLA4 | A | 5.08E−16 | RA T1D |

| 3p14.3 | 58,183,636 | rs35677470 | DNASE1L3 | A | 1.04E−11 | RA SSc |

| 3q25.33 | 159,647,674 | rs17753641 | IL12A | G | 1.64E−29 | CeD SSc* |

| 4p15.2 | 26,088,128 | rs16878091 | RBPJ | A | 2.53E−12 | RA T1D |

| 5q33.1 | 150,438,988 | rs1422673 | TNIP1 | T | 1.87E−09 | CeD RA SSc |

| 6q15 | 90,976,768 | rs72928038 | BACH2 | A | 9.34E−12 | CeD RA T1D |

| 6q23.3 | 138,003,822 | rs11757201 | TNFAIP3 | C | 1.27E−11 | CeD RA T1D |

| 6q23.3 | 138,243,739 | rs58721818 | TNFAIP3 | T | 5.26E−10 | RA SSc |

| 6q25.3 | 159,470,417 | rs212407 | TAGAP | G | 6.74E−14 | CeD RA T1D |

| 7p14.1 | 37,382,465 | rs60600003 | ELMO1 | G | 4.25E−13 | CeD SSc |

| 7p12.1 | 51,015,193 | rs7780389 | COBL | T | 2.25E−08 | RA T1D |

| 7q32.1 | 128,572,766 | rs4731532 | IRF5 | A | 1.25E−10 | RA SSc |

| 9p13.3 | 34,710,260 | rs2812378 | CCL21 | G | 1.04E−09 | CeD RA |

| 10p15.1 | 6,101,713 | rs3118470 | IL2RA | C | 5.92E−09 | RA T1D |

| 10p15.1 | 6,116,254 | rs72776098 | IL2RA | A | 7.10E−10 | SSc T1D |

| 10p15.1 | 6,390,450 | rs947474 | PRKCQ | G | 1.28E−08 | CeD RA T1D |

| 10p14 | 8,102,272 | rs3802604 | GATA3 | G | 4.67E−08 | RA T1D |

| 10q22.3 | 81,045,280 | rs1250568 | ZMIZ1 | C | 3.87E−15 | CeD SSc T1D |

| 11q23.3 | 118,726,843 | rs10892299 | DDX6 | T | 2.25E−13 | CeD SSc T1D |

| 12q13.2 | 56,470,625 | rs11171739 | IKZF4 | C | 1.87E−20 | RA T1D |

| 15q14 | 38,828,140 | rs8043085 | RASGRP1 | T | 1.53E−08 | RA T1D |

| 15q25.1 | 79,234,957 | rs34593439 | CTSH | A | 1.47E−14 | CeD T1D |

| 17q12 | 38,033,277 | rs1054609 | ORMDL3 | C | 3.70E−08 | RA SSc T1D |

| 18p11.21 | 12,777,573 | rs2542148 | PTPN2 | C | 5.11E−16 | CeD T1D |

| 19p13.2 | 10,427,721 | rs74956615 | TYK2 | A | 1.62E−17 | RA SSc T1D |

| 21q22.3 | 43,855,067 | rs1893592 | UBASH3A | C | 4.86E−12 | CeD T1D |

| 22q11.1 | 21,936,152 | rs66534072 | YDJC | G | 2.05E−08 | CeD SSc |

The selected lead SNP in each region is shown, together with the best subset obtained from the subset-based meta-analysis. Position (bp), base pair position in hg19; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; Gene, annotated gene as described in methods; A1, alternative allele used in the logistic regression; P2sided, p value from the two-sided subset-based meta-analysis; Best subset, phenotypes contributing to the association signal. Diseases included in the best subset and for which identified associations have not been previously reported are shown in bold; novel signals within known risk loci are indicated by “*”

On the other hand, an opposite effect was observed for ten of the shared genetic variants that mapped on ITGA4, IL12A, TNIP1, TAGAP, COBL, IL2RA, ZMIZ1, DDX6, IKZF4, and CTSH regions (Additional file 2: Figure S4 and Table S3). For example, the minor allele (G) of the IL12A rs17753641 polymorphism, which has been previously reported to confer risk to CeD, had a protective effect for SSc in our study. In addition, an opposite effect was also observed for the TAGAP rs212407 variant, which appeared to confer risk to CeD and protection to RA and T1D, as previously described [6, 27].

In order to validate our findings, the pleiotropic role of the shared variants identified by ASSET was evaluated using the CCMA approach. As shown in Additional file 1: Table S4, 34 of the 38 SNPs had a pleiotropic effect according to CCMA (best model including at least two diseases). It should be noted that the second best model obtained with this method yielded z-scores very similar to those of the best model. In this regard, when considering either of the two best models, all pleiotropic SNPs identified by ASSET showed shared effects across diseases in the CCMA (Additional file 1: Table S4). Furthermore, we observed a high concordance rate between the best subset of diseases identified by ASSET and the best models (best or second best model) according to CCMA. Specifically, best models completely matched between both methods for 29 of the 38 SNPs (concordance rate of 0.76). In addition, for the remaining 9 pleiotropic variants, best models partially overlapped between ASSET and CCMA and, in all the cases except one, diseases contributing to the association signal according to ASSET were included in the best model of CCMA (Additional file 1: Table S4). For instance, whereas ASSET identified two diseases (CeD and SSc) contributing to the association signal observed for rs60600003, the best model obtained with CCMA included three diseases, the two already forming part of the best subset of ASSET (CeD, SSc) and RA. Considering those SNPs for which the best model overlapped totally or partially between both approaches, the concordance rate between ASSET and CCMA was 0.87, considering the best model of CCMA, and 1, considering the best or second best model of CCMA. This analysis confirms the high reliability of our cross-disease meta-analysis results, strongly supporting the role of the 38 genetic variants as pleiotropic risk factors in autoimmunity.

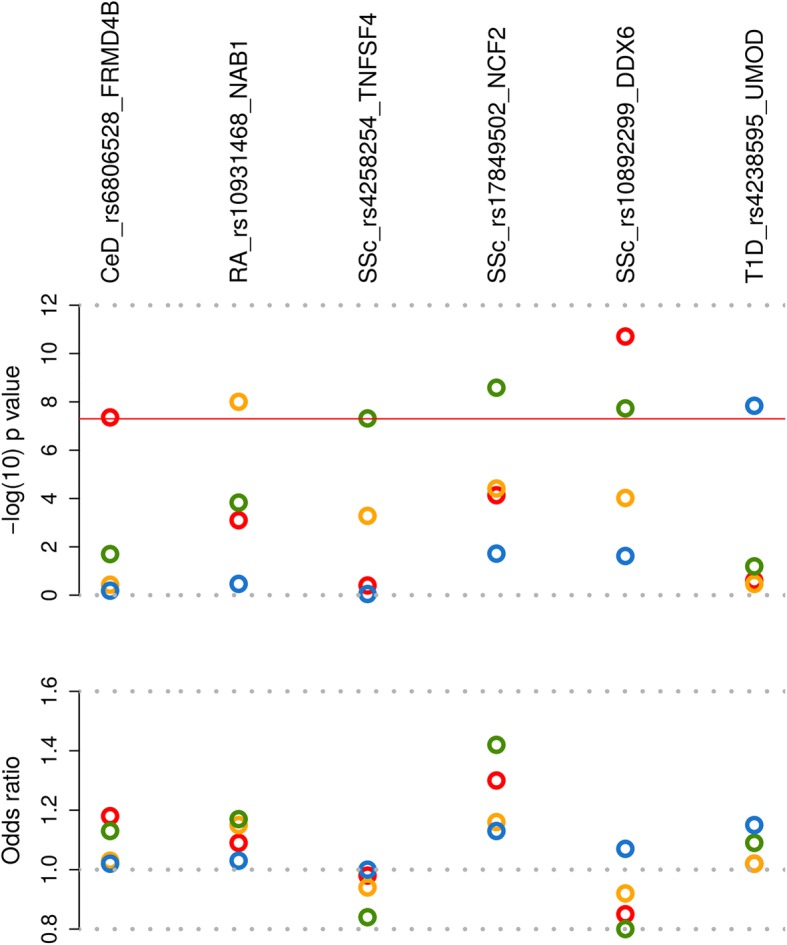

Identification of novel individual-disease associations

Of the 34 shared risk loci identified, 20 have already been reported as risk factors for the diseases contributing to the association, according to Immunobase and the GWAS catalog [18, 19], whereas 14 of them (more than 40%) represent potentially new loci for at least one of the diseases included in the best subset (Table 1). Considering this, we checked whether these pleotropic variants were associated at genome-wide level of significance with any of the diseases contributing to each specific signal. Two of the common variants, rs10931468 (mapping on the NAB1 region, 2q32.3) and rs10892299 (mapping on the DDX6 region, 11q23.3), were associated with RA and SSc, respectively (Fig. 1, Additional file 2: Figures S5a and S6a, and Additional file 1: Table S2); hence they represent novel genetic risk factors for these diseases. The rs10931468 genetic variant is located within the NAB1 gene, near STAT4 (Table 1). However, this SNP is not linked to the STAT4 variants previously associated with the diseases under study (D’ < 0.13 and r2 < 0.012). In fact, this SNP showed an independent effect in the RA meta-analysis after conditioning on the most associated variants within the region (Additional file 2: Figure S5b).

Fig. 1.

Novel genome-wide associated loci for celiac disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis and type 1 diabetes. Pleiotropic SNPs reaching genome-wide significance level and SNPs associated with a single disease and reaching p values lower than 5 × 10− 6 in the subset-based meta-analysis were checked for genome-wide association in each of the diseases included in the best subset. Negative log10-tranformed p value (disease-specific p values) (upper plot) and odds ratio (lower plot) for the new genome-wide signals are shown. The six loci are annotated with the candidate gene symbol. Circles represent the analyzed diseases (red: celiac disease; yellow: rheumatoid arthritis; green: systemic sclerosis; blue: type 1 diabetes). The red line represents genome-wide level of significance (p = 5 × 10− 8)

In addition, to avoid any loss of power, SNPs associated with a single disease and reaching p values lower than 5 × 10− 6 in the subset-based meta-analysis were checked for association in each specific disorder. Using this strategy, we identified four novel single-disease genome-wide associations, one for CeD (rs6806528 at FRMD4B), two for SSc (rs4258254 at TNFSF4 and rs17849502 at NCF2), and one for T1D (rs4238595 at UMOD) (Fig. 1, Additional file 2: Figures S6-S8, and Additional file 1: Table S5).

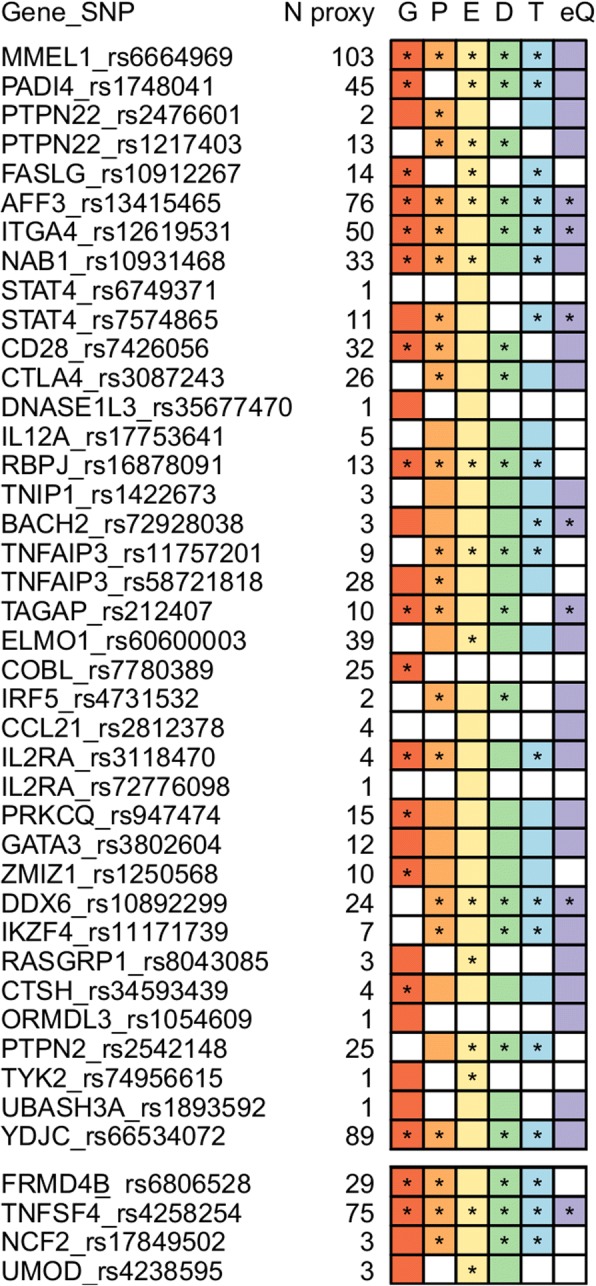

Functional annotation of associated variants

SNP annotation showed that only 5% of the pleiotropic SNPs were coding, including two missense variants (Additional file 1: Table S2), whereas five of the non-coding SNPs (13%) were in tight LD (r2 ≥ 0.8) with coding variants (three missense, one synonymous and one splice donor) (Additional file 2: Table S6). Two of the non-synonymous polymorphisms, rs35677470 within DNASE1L3 and rs2289702 (a proxy for rs34593439) within CTSH, appeared to have a deleterious effect according to SIFT (Additional file 1: Table S2). Of the four new single-disease signals, three were non-coding polymorphisms and one was a missense variant (Additional file 1: Table S5).

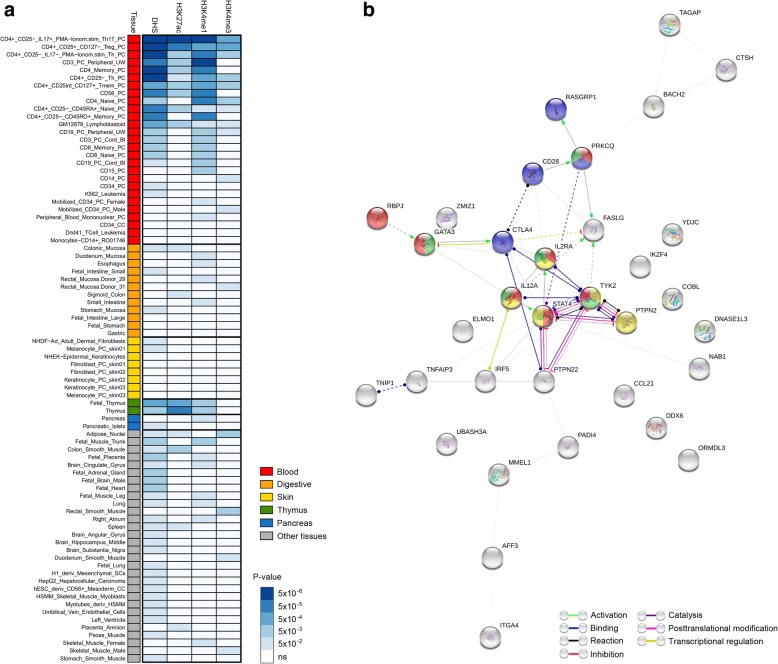

Considering that most of the associated genetic variants did not show direct effects on protein function, we identified all SNPs in high LD (r2 ≥ 0.8) with both pleiotropic and single-disease lead signals and evaluated their possible functional implications. We checked for overlap between the lead and proxy SNPs and functional annotations from the Roadmap Epigenomics, ENCODE and GTEx projects, including conserved positions, histone modifications at promoters and enhancers, DHS, TFBS, and eQTL. As shown in Fig. 2, all pleiotropic SNPs lie in predicted regulatory regions in immune cell lines or whole blood, whereas 76% overlap with more than three functional annotations. In addition, most of them appear to act as eQTLs, thereby affecting gene expression levels (Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Table S7).

Fig. 2.

Functional annotation of 38 pleiotropic polymorphisms (p < 5 × 10–8 in the subset-based meta-analysis) and four single-disease associated variants (p < 5 × 10–6 in the subset-based meta-analysis and p < 5 × 10–8 in disease-specific meta-analyses). Haploreg v4.1 was used to explore whether lead SNPs, and their proxies (r2 ≥ 0.8), overlapped with different regulatory datasets from the Roadmap Epigenomics project, the ENCODE Consortium and more than ten eQTL studies in immune cell lines, cell types relevant for each specific disorder and/or whole blood. Colors denote both lead and proxy SNPs overlapping with the different regulatory elements analyzed: G (red): conserved positions (Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling, GERP); P (orange): promoter histone marks; E (yellow): enhancer histone marks; D (green): DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHS); T (blue): transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs); eQ (purple): expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL). Functional annotations overlapping with proxy SNPs are marked with an asterisk. N proxy, number of proxy SNPs for each lead variant. The different loci are annotated with the candidate gene symbol

Similarly, all single-disease-associated variants also overlapped with regulatory elements in whole blood, immune cells, and/or cell types relevant for each specific disorder (Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Table S7).

Enrichment in tissue-specific regulatory elements and biological pathways

Subsequently, to determine whether the set of 38 independent pleiotropic SNPs was enriched for regulatory elements in specific cell types, we performed a hypergeometric test using GenomeRunner [23]. Specifically, we checked for overrepresentation of DHSs, histone modifications (H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3), and TFBSs in human cell lines and tissues from the ENCODE and Roadmap Epigenomics projects. Results of this analysis are shown in Fig. 3a and Additional file 1: Table S8. Pleiotropic SNPs showed overrepresentation of DHSs in different subsets of T cells, with the strongest enrichment pointing to regulatory T (Treg) cells, T helper memory and naive cells, and Th17 lymphocytes. Similarly, the H3k4me1, H3k27ac, and H3k4me3 histone marks—which are especially informative of most active enhancer and promoter regulatory regions—were also overrepresented in these specific cell types (Fig. 3a and Additional file 1: Table S8). In addition, shared genetic variants were enriched for targets of 12 TFs, with BATF (PBH = 6.40E−15), RelA (PBH = 6.11E−12), and IRF4 (PBH = 1.88E−08) showing the strongest overrepresentation (Additional file 2: Table S9).

Fig. 3.

Functional regulatory elements and PPI enrichment analysis. a Heat map showing DNase 1 hypersensitive sites (DHSs) and histone marks enrichment analysis of the set of pleiotropic variants. GenomeRunner web server was used to determine whether the set of pleiotropic SNPs significantly co-localize with regulatory genome annotation data in 127 cell types from the Roadmap Epigenomics project. First column shows cell types grouped and colored by tissue type (color-coded as indicated in the legend). Tissues relevant for the autoimmune diseases studied as well as other tissues for which any of the analyzed functional annotations showed a significant enrichment p value (p < 0.05 after FDR correction) are shown. The remaining four columns denote the analyzed functional annotations, DHSs, H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3. Results of the enrichment analysis are represented in a scale-based color gradient depending on the p value. Blue indicates enrichment and white indicates no statistical significance after FDR adjustment. b Interaction network formed for the set of common genes. Direct and indirect interactions among genes shared by different disease subgroups were assessed using STRING. Plot shows results of the “molecular action” view such that each line shape indicates the predicted mode of action (see legend). Genes involved in the biological pathways enriched among the set of pleiotropic loci (Additional file 2: Table S10) are shown in color: red: Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation; green: Th17 cell differentiation; yellow: Jak-STAT signaling pathway; blue: T cell receptor signaling pathway

We further conducted PPI and KEGG pathway analysis to gain insight into the biological processes affected for the set of common genes. By constructing a network of direct and indirect interactions, we found a main cluster enriched for proteins involved in Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation (PBH = 6.21E−07), Jak-STAT signaling pathway (PBH = 4.53E−03), T cell receptor signaling pathway (PBH = 7.85E−03), and Th17 cell differentiation (PBH = 7.85E−03) (Fig. 3b and Additional file 2: Table S10).

Identification of potential drug targets

Finally, in order to identify potentially new leads for therapies for CeD, RA, SSc, and T1D, we investigated whether proteins encoded by pleiotropic genes—or any gene in direct PPI with them—are targets for approved, clinical trial, or experimental pharmacologically active drugs. Using this approach, we found 26 potentially repositionable drugs: 8 indicated for RA that would be worth exploring for CeD, SSc, and/or T1D treatment and 18 with other indications that could be promising candidates for the treatment of at least two of the four autoimmune diseases under study (Table 2). Interestingly, 15 of the 19 drug targets identified among the set of common genes are involved in the biological pathways overrepresented in the set of autoimmune disease common genes (Fig. 3b).

Table 2.

Common genes in autoimmunity identified as targets for drugs

| Annotated gene | Genes in direct PPI | Targeted drugs | Action | Indication | Potential new clinical application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicated for CeD, RA, T1D, and/or SSc | |||||

| CD28 | CD80 | Abatacept | Antagonist | RA | CeD |

| IL12A/TYK2 | IL6R | Tocilizumab | Antibody | RA | CeD, SSc, T1D |

| Sarilumab | Antagonist, antibody | RA | |||

| IL1R1 | Anakinra | Antagonist | RA | ||

| PTPN2/STAT4 | JAK1/JAK2/JAK3 | Tofacitinib | Inhibitor | RA | CeD, SSc, T1D |

| TNFAIP3 | TNF | Etanercept | Antibody | RA | CeD, SSc, T1D |

| Adalimumab | Antibody | RA | |||

| Infliximab | Inhibitor | RA | |||

| Other indications | |||||

| CD28 | CD2 | Alefacept | Inhibitor | Psoriasis | CeD, RA |

| CD28/IL12A/IL2RA/STAT4/TYK2 | IFNG | Olsalazine | NA | Inflammatory bowel disease | CeD, RA, SSc, T1D |

| CCL21 | C5 | Eculizumab | Antibody | Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria | CeD, RA |

| CXCR4 | Plerixafor | Antagonist | Cancer | ||

| CCL21/IL12A/TYK2 | CCR5 | Maraviroc | Antagonist | HIV | CeD, RA, SSc, T1D |

| CTLA4 | Ipilimumab | NA | Cancer | RA, T1D | |

| FASLG/IL12A/IL2RA/IRF5/STAT4/TYK2 | IL12B | Ustekinumab | Antibody | Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis | CeD, RA, SSc, T1D |

| IL12A/IL2RA/TYK2 | IL3RA | Sargramostim | Agonist | Cancer | CeD, RA, SSc, T1D |

| IL12A/IRF5/TYK2 | IL1B | Canakinumab | Binder | Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis | CeD, RA, SSc, T1D |

| IL12A/TYK2 | IFNGR1 | Interferon gamma-1b | Chronic granulomatous disease | CeD, RA, SSc, T1D | |

| IL2RA | Aldesleukin | Agonist, Modulator | Cancer | CeD, RA, SSc, T1D | |

| Basiliximab | Antibody | Kidney transplant rejection | |||

| Daclizumab | Antibody | Multiple sclerosis | |||

| Denileukin diftitox | Binder | Cancer | |||

| IL2RA/IRF5/TYK2 | IL6 | Siltuximab | Antagonist antibody | Castleman’s disease | CeD, RA, SSc, T1D |

| IL2RA/STAT4/TYK2 | IL23A | Guselkumab | Blocker | Psoriasis | CeD, RA, SSc, T1D |

| ITGA4 | Natalizumab | Antibody | Multiple sclerosis | CeD, SSc | |

| Vedolizumab | Antibody | Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis | |||

Target genes for both drugs used for the treatment of the studied autoimmune diseases as well as drugs used for other indications are shown in the Table. NA, not available. Last column indicates those diseases that could potentially benefit from drug repositioning, since they are contributing (included in the best subset) to the association signal/s observed within each locus

Discussion

Through a large cross-disease meta-analysis of Immunochip data from four seropositive autoimmune disorders, CeD, RA, SSc, and T1D, we have been able to advance in the knowledge of the genetic overlap existing in autoimmunity. Specifically, our meta-analysis identified 38 genetic variants shared among subsets of the diseases under study, five of which, including PADI4, NAB1, COBL, CCL21, and GATA3, represent new shared genetic risk loci. Moreover, ten of the 38 pleiotropic variants showed opposite allelic effects across phenotypes contributing to the association signal, thus indicating the complexity of the molecular mechanisms by which SNPs affect autoimmune diseases.

Consistent with previous findings [28], functional annotation of these pleiotropic polymorphisms suggested that the majority of multi-disease signals affect disease risk by altering gene regulation. Interestingly, tissue-specific enrichment analysis for regulatory elements suggested a specific regulatory role of the pleiotropic variants in Th17 and Treg cells, thus pointing to a crucial contribution of these cell types to the pathogenic mechanisms shared by these disorders. In addition, enrichment for targets of several TFs, mainly BATF, RelA, and IRF4, was also evident. It should be noted that BATF and IRF4 are both required for the differentiation of Th17 cells [29], whereas RelA is crucial for Treg-induced tolerance [30]. According to this data, pleiotropic variants could potentially regulate gene expression by disrupting motifs recognized for TFs in different subsets of T cells, mainly Th17 and Treg lymphocytes. Subsequently, results from pathway enrichment analysis confirmed the relevant contribution of pleiotropic variants and target genes in T cell-mediated immunity. Moreover, drug repositioning analysis evidenced several candidate drugs with potential new clinical use for the diseases under study. Notably, most of these drugs were directed against proteins involved in the biological processes overrepresented among the set of common genes and, therefore, their potential clinical application to the treatment of CeD, RA, SSc, and T1D appeared to be of special interest. However, it should be considered that both the functional effects of pleiotropic variants as well as the disease-causal genes remain elusive in most cases, thus representing a limitation for drug repositioning. In addition, ten of these shared genetic variants showed opposite effects across diseases and, therefore, the complexity of molecular mechanisms by which SNPs affect autoimmune diseases should be taken into account when prioritizing drugs based on repositioning studies.

Furthermore, we also reported six new genome-wide associations for the diseases under study. We identified two new susceptibility loci for RA and SSc among the pleiotropic signals. The dense genotyping of immune-related loci provided by the Immunochip platform allowed identifying NAB1 as a new susceptibility locus for RA within the 2q22.3 region, which also contains the pan-autoimmune susceptibility gene STAT4. In addition, interrogation of publicly available eQTL data sets showed that the associated NAB1 variant, rs10931468, acts as an eQTL affecting NAB1 expression in lymphoblastoid cell lines. NAB1 encodes the NGFI-A binding protein 1, which has been shown to form a complex with Egr3 involved in the silencing of interferon gamma receptor 1 (ifngr1). Specifically, Nab1 was required for deacetylation of the ifngr1 promoter and downregulation of cell surface receptor [31]. On the other hand, an intergenic variant located near DDX6 was also identified as a new genetic risk locus for SSc. This gene encodes a member of the DEAD box protein family recently identified as a suppressor of interferon-stimulated genes [32].

Additionally, some of the single-disease genome-wide associations identified in the present study had not been previously reported. The FRMD4B locus was found to be associated with CeD. Although genetic variants within the FRMD4B region have been previously involved in disease susceptibility [33, 34], our study is the first one reporting an association between CeD and this locus at the genome-wide significance level. FRMD4B, encoding a scaffolding protein (FERM domain containing 4B protein), has not been described before in relation to any autoimmune disorder, representing a CeD-specific risk locus.

Regarding SSc, two new genetic risk loci were identified. According to the subset-based meta-analysis results, SSc was the only phenotype contributing to the association signal detected within the 1q25.1 region; however, this locus is also a known susceptibility factor for RA [35]. Indeed, several SNPs within this region showed pleiotropic effects in RA and SSc in the cross-disease meta-analysis, but they did not reach genome-wide significance (top RA-SSc common signal: p value = 5.86E−06). A relevant gene for the immune response, TNFSF4, is located within the 1q25.1 region; nevertheless, functional annotation revealed that the rs10798269 SNP (a proxy for the top associated variant) acted as a trans-eQTL influencing the expression level of the PAG1 gene (p value = 4.20E−06). Strikingly, PAG1, residing on chromosome region 8q21.13, encodes a transmembrane adaptor protein that binds to the tyrosine kinase csk participating in the negative control of the signaling mediated by the T cell receptor (TCR) [36]. It should be noted that CSK is an established risk locus for SSc [37]. A second novel genome-wide association for SSc was identified within the 1q25.3 region. The strongest signal belonged to a missense variant (rs17849502), also associated with systemic lupus erythematosus [38], which leads to the substitution of histidine-389 with glutamine (H389Q) in the PB1 domain of the neutrophil cytosolic factor 2 (NCF2) protein. NCF2 is part of the multi-protein NADPH oxidase complex found in neutrophils. Interestingly, it has been shown that the 389Q mutation has a functional implication, causing a twofold decrease in reactive oxygen species production [38].

Finally, a genetic variant (rs4238595) located downstream of the UMOD gene, encoding uromodulin, was identified as a new genetic risk factor for T1D. Interestingly, a SNP linked to this variant showed nominal association in a previous GWAS performed in this disorder [39]. This locus has also been implicated in diabetic kidney disease [40]. Nevertheless, no association with any other immune-related condition has been described so far and, therefore, this locus represents a T1D-specific association. In addition, functional annotation of the lead variant and their proxies showed an overlap with enhancer histone marks and DHSs specifically in pancreas, which supports its potential role in the T1D pathogenesis.

Conclusions

In summary, by conducting a subset-based meta-analysis of Immunochip data from four seropositive autoimmune diseases, we have increased the number of pleiotropic risk loci in autoimmunity, identified new genome-wide associations for CeD, SSc, RA, and T1D and shed light on common biological pathways and potential functional implications of shared variants. Knowledge of key shared molecular pathways in autoimmune diseases may help identify putative common therapeutic mechanisms. In this regard, we identified several drugs used for other indications that could be repurposed for the treatment of the autoimmune diseases under study. Thus, a new classification of patients based on molecular profiles, rather than clinical manifestations, will make it possible for individuals with a certain autoimmune disorder to benefit from therapeutic options currently used to treat another disease with which they share etiological similarities.

Due to the design of the Immunochip, all shared pathways identified in our study were related to immune regulation. Hopefully, future cross-disease studies using GWAS data will allow identification of non-immune loci and pathways shared in autoimmunity.

Additional files

Table S1. Case/control datasets included in the study. Table S2. Loci reaching genome-wide level of significance in the subset-based meta-analysis and showing independent effect after linkage disequilibrium (LD)-clumping (r2 < 0.05 within 500 kB up- or downstream of the lead SNP). Table S4. Comparison of the results obtained with ASSET and CCMA for the 38 pleiotropic variants identified in our study. Table S5. Novel genome-wide associations for celiac disease, systemic sclerosis and type 1 diabetes (p value < 5 × 10–6 in the subset based meta-analysis and p value < 5 × 10–8 in each disease-specific meta-analysis). Table S7. Potential role of the lead polymorphisms (pleiotropic and single-disease associated variants), and their proxies (r2 ≥ 0.8) as expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) in whole blood, immune cell lines or tissues relevant for the diseases under study. Table S8. Specific cell types showing enrichment among regulatory DNA elements, Dnase 1 hypersensitivity sites and histone marks, and pleiotropic variants. (XLSX 77 kb)

Table S3. Results of the subset-based meta-analysis for the lead variants showing evidence of opposite allelic effect across the autoimmune diseases contributing to the association signal. Table S6. Coding variants in tight linkage disequilibrium (r2 ≥ 0.8) with lead non-coding polymorphisms according to the European population of the 1000 Genomes Project. Table S9. Transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) potentially disrupted by the set of pleiotropic variants. Table S10. Biological pathways significantly enriched among the set of common genes. Figure S1. Quantile–quantile plots for the p values of each individual disease, celiac disease (a), rheumatoid arthritis (b), systemic sclerosis (c), and type 1 diabetes (d), and the cross disease meta-analysis (e). Figure S2. Empirical −log10(P)-distribution of the Zmax statistic obtained by simulating 300 × 106 replicates of four normally distributed random variables. Figure S3. Manhattan plot of the subset-based meta-analysis of Immunochip data from celiac disease (CeD), systemic sclerosis (SSc), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and type 1 diabetes (T1D). Figure S4. Disease-specific odds ratio for the pleiotropic variants showing opposite allelic effects across autoimmune diseases. Figure S5. Regional association plots of the novel genome-wide associated locus for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), 2q32.3. Figure S6. Regional association plots of the novel genome-wide associated loci for systemic sclerosis (SSc), 11q23.3 (a), 1q25.1 (b), and 1q25.3 (c). Figure S7. Regional association plot of the novel genome-wide associated locus for celiac disease (CeD), 3p14.1. Figure S8. Regional association plot of the novel genome-wide associated locus for type 1 diabetes (T1D), 16p12.3. Members of the Coeliac Disease Immunochip Consortium, Members of the RACI, Members of the International Scleroderma Group, Members of the Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium (T1DGC). (PDF 1590 kb)

Summary statistics from the cross-disease meta-analysis using ASSET. (TXT 38863 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sofía Vargas, Sonia García, and Gema Robledo for their excellent technical assistance, and all the patients and healthy controls for kindly accepting their essential collaboration. A full list of the members of the Coeliac Disease Immunochip Consortium, RACI, International Scleroderma Group, and Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium can be found in Additional file 2.

Funding

This work was supported by the following grants: SAF2015-66761-P from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, P12-BIO-1395 from Consejería de Innovación, Ciencia y Tecnología, Junta de Andalucía (Spain), PI-0493-2016 from Consejería de Salud, Junta de Andalucía (Spain) and the Cooperative Research Thematic Network (RETICS) programme (RD16/0012/0013) (RIER), from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII, Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness). AM is a recipient of a Miguel Servet fellowship (CP17/00008) from ISCIII (Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness). CW is supported by FP7/2007-2013/ERC Advanced Grant (agreement 2012–322698), the Stiftelsen K.G. Jebsen Coeliac Disease Research Centre (Oslo, Norway), and a Spinoza Prize from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO SPI 92-266). This research utilizes resources provided by the Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium, a collaborative clinical study sponsored by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International (JDRF) and supported by U01 DK062418.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- ACSL4

Acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4

- BATF

Basic leucine zipper ATF-like transcription factor

- CCL21

C–C motif chemokine ligand 21

- CeD

Celiac disease

- COBL

Cordon-bleu WH2 repeat protein

- CSK

C-terminal Src kinase

- CTSH

Cathepsin H

- DDX6

DEAD-box helicase 6

- DHS

DNase I hypersensitive site

- DNASE1L3

Deoxyribonuclease 1 like 3

- eQTL

Expression quantitative trait locus

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FRMD4B

FERM domain containing 4B

- GATA3

GATA binding protein 3

- GERP

Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- H3K27ac

Acetylation of histone H3 at lysine 27

- H3K4me1

Mono-methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4

- H3K4me3

Tri-methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- IL12A

Interleukin 12A

- IRF4

Interferon regulatory factor 4

- Jak

Janus kinase

- KEEG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- NAB1

NGFI-A binding protein 1

- NCF2

Neutrophil cytosolic factor 2

- PADI4

Peptidyl arginine deiminase 4

- PAG1

Phosphoprotein membrane anchor with glycosphingolipid microdomains 1

- PC

Principal component

- PPI

Protein-protein interaction

- PTPN22

Protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 22

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RelA

RELA proto-oncogene, NF-kB subunit

- SD

Standard deviation

- SLC22A5

Solute carrier family 22 member 5

- SNP

Single-nucleotide polymorphism

- SSc

Systemic sclerosis

- STAT4

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 4

- T1D

Type 1 diabetes

- TAGAP

T cell activation RhoGTPase activating protein

- TF

Transcription factor

- TFBS

Transcription factor binding site

- TNFSF4

TNF superfamily member 4

- Treg

Regulatory T cell

- UMOD

Uromodulin

Authors’ contributions

AM and JM were involved in the conception and design of the study. AM and MK performed analyses. AZ, JG-A, W-MC, SO-G, IG-A, LR-R, RR-F, MAG-G, MDM, SR, SSR, and CW were involved in study subject and data recruitment and participated in interpretation of the data. AM and JM drafted the manuscript. All authors revised critically the manuscript draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and the design of the work was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Spanish National Research Council and the local ethical committees of the different participating institutions. Research was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ana Márquez, Email: anamaort@ipb.csic.es.

Martin Kerick, Email: mkerick@ipb.csic.es.

Alexandra Zhernakova, Email: sashazhernakova@gmail.com.

Javier Gutierrez-Achury, Email: javiergutierreza@gmail.com.

Wei-Min Chen, Email: wmchen@virginia.edu.

Suna Onengut-Gumuscu, Email: so4g@eservices.virginia.edu.

Isidoro González-Álvaro, Email: isidoro.ga@ser.es.

Luis Rodriguez-Rodriguez, Email: lrodriguezr.hcsc@salud.madrid.org.

Raquel Rios-Fernández, Email: rriosfer@hotmail.com.

Miguel A. González-Gay, Email: miguelaggay@hotmail.com

Maureen D. Mayes, Email: Maureen.D.Mayes@uth.tmc.edu

Soumya Raychaudhuri, Email: ssr4n@eservices.virginia.edu.

Stephen S. Rich, Email: soumya@broadinstitute.org

Cisca Wijmenga, Email: c.wijmenga@umcg.nl.

Javier Martín, Email: javiermartin@ipb.csic.es.

Coeliac Disease Immunochip Consortium:

Gosia Trynka, Karen A. Hunt, Nicholas A. Bockett, Jihane Romanos, Vanisha Mistry, Agata Szperl, Sjoerd F. Bakker, Maria Teresa Bardella, Leena Bhaw-Rosun, Gemma Castillejo, Emilio G. de la Concha, Rodrigo Coutinho de Almeida, Kerith-Rae M. Dias, Cleo C. van Diemen, Patrick C. A. Dubois, Richard H. Duerr, Sarah Edkins, Lude Franke, Karin Fransen, Javier Gutierrez, Graham A. R. Heap, Barbara Hrdlickova, Sarah Hunt, Leticia Plaza Izurieta, Valentina Izzo, Leo A. B. Joosten, Cordelia Langford, Maria Cristina Mazzilli, Charles A. Mein, Vandana Midah, Mitja Mitrovic, Barbara Mora, Marinita Morelli, Sarah Nutlan, Kerra Pearce, Mathieu Platteel, Isabel Polanco, Simon Potter, Carmen Ribes-Koninckx, Isis Ricaño-Ponce, Anna Rybak, José Luis Santiago, Sabyasachi Senapati, Ajit Sood, Hania Szajewska, Riccardo Troncone, Jezabel Varadé, Chris Wallace, Victorien M. Wolters, Alexandra Zhernakova, B. K. Thelma, Bozena Cukrowska, Elena Urcelay, Jose Ramon Bilbao, M. Luisa Mearin, Donatella Barisani, Jeffrey C. Barrett, Vincent Plagnol, Cisca Wijmenga, and David A. van Heel

Rheumatoid Arthritis Consortium International for Immunochip (RACI):

Steve Eyre, John Bowes, Dorothée Diogo, Annette Lee, Anne Barton, Paul Martin, Alexandra Zhernakova, Eli Stahl, Sebastien Viatte, Kate McAllister, Christopher I. Amos, Leonid Padyukov, Rene E. M. Toes, Tom W. J. Huizinga, Cisca Wijmenga, Gosia Trynka, Lude Franke, Harm-Jan Westra, Lars Alfredsson, Xinli Hu, Cynthia Sandor, Sonia Davila, Chiea Chuen Khor, Khai Koon Heng, Robert Andrews, Sarah Edkins, Sarah E. Hunt, Cordelia Langford, Deborah Symmons, Pat Concannon, Stephen S. Rich, Miguel A. Gonzalez-Gay, Luis Rodriguez-Rodriguez, Lisbeth Ärlsetig, Javier Martin, Solbritt Rantapää-Dahlqvist, Robert M. Plenge, Soumya Raychaudhuri, Lars Klareskog, Peter K. Gregersen, and Jane Worthington

International Scleroderma Group:

Maureen D. Mayes, Lara Bossini-Castillo, Olga Gorlova, Xiaodong Zhou, Wei V. Chen, Shervin Assassi, Jun Ying, Filemon K. Tan, Frank C. Arnett, John D. Reveille, Sandra Guerra, Peter K. Gregersen, Annette T. Lee, Carmen Pilar Simeón, Patricia Carreira, Iván Castellví, Miguel A. González-Gay, Lorenzo Beretta, Alexander E. Voskuyl, Paolo Airò, Claudio Lunardi, Paul Shiels, Jacob M. van Laar, Ariane Herrick, Jane Worthington, Christopher P. Denton, Jasper Broen, Timothy R. D. J. Radstake, Carmen Fonseca, Bobby P. Koeleman, Javier Martin, Raquel Ríos, Jose Luis Callejas, José Antonio Vargas Hitos, Rosa García Portales, María Teresa Camps, Antonio Fernández-Nebro, María F. González-Escribano, Francisco José García-Hernández, Mª. Jesús Castillo, Mª. Ángeles Aguirre, Inmaculada Gómez-Gracia, Luis Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Paloma García de la Peña, Esther Vicente, José Luis Andreu, Mónica Fernández de Castro, Francisco Javier López-Longo, Lina Martínez, Vicente Fonollosa, Alfredo Guillén, Gerard Espinosa, Carlos Tolosa, Anna Pros, Mónica Rodríguez Carballeira, Francisco Javier Narváez, Manel Rubio Rivas, Vera Ortiz-Santamaría, Ana Belén Madroñero, Bernardino Díaz, Luis Trapiella, Adrián Sousa, María Victoria Egurbide, Patricia Fanlo Mateo, Luis Sáez-Comet, Federico Díaz, Vanesa Hernández, Emma Beltrán, José Andrés Román-Ivorra, Elena Grau, Juan José Alegre-Sancho, Francisco J. Blanco García, Natividad Oreiro, Norberto Ortego-Centeno, Mayka Freire, Benjamín Fernández-Gutiérrez, Alejandro Balsa, Ana M. Ortiz, Jeska de Vries-Bouwstra, Cesar Magro-Checa, Alessandro Santaniello, Chiara Bellocchi, Gianluca Moroncini, and Armando Gabrielli

Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium:

Ellen Adlem, James Allen, Jeffrey Barrett, Judy Brown, Oliver Burren, Pamela Clarke, David Clayton, Gillian Coleman, Jason Cooper, Francesco Cucca, Lucy Davison, Kate Downes, Simon Duley, David Dunger, Laura Esposito, Vin Everett, Sarah Field, Jason Hafler, Matthew Hardy, Deborah Harrison, Inge Harrison, Steve Hawkins, Barry Healy, Simon Hood, Simon Howell, Meeta Maisuria, William Meadows, Trupti Mistry, Sergey Nezhenstsev, Sarah Nutland, Nigel Ovington, Vincent Plagnol, Dan Rainbow, Kara Rainbow, Srilakshmi Raj, Helen Schuilenburg, Anna Simpson, Luc Smink, Debbie Smyth, Helen Stevens, Niall Taylor, John Todd, Jaakko Tuomilehto, Neil Walker, Linda Wicker, Barry Widmer, Mark Wilson, Heather Withers, Jennie Yang, Mark Brown, Arnetta Crews, Jason Griffin, Mark Hall, Teresa Harnish, John Hepler, Joan Hilner, Nancy King, Kurt Lohman, Lingyi Lu, Josyf Mychaleckyj, Jay Nail, Letitia Perdue, June Pierce, David Reboussin, Scott Rushing, Michele Sale, Elizabeth Sides, Beverly Snively, Hoa Teuschler, Goodrich Theil, Lynne Wagenknecht, and Dustin Williams

References

- 1.Cooper GS, Bynum ML, Somers EC. Recent insights in the epidemiology of autoimmune diseases: improved prevalence estimates and understanding of clustering of diseases. J Autoimmun. 2009;33(3–4):197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richard-Miceli C, Criswell LA. Emerging patterns of genetic overlap across autoimmune disorders. Genome Med. 2012;4(1):6. doi: 10.1186/gm305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhernakova A, van Diemen CC, Wijmenga C. Detecting shared pathogenesis from the shared genetics of immune-related diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(1):43–55. doi: 10.1038/nrg2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellinghaus D, Jostins L, Spain SL, Cortes A, Bethune J, Han B, Park YR, Raychaudhuri S, Pouget JG, Hubenthal M, et al. Analysis of five chronic inflammatory diseases identifies 27 new associations and highlights disease-specific patterns at shared loci. Nat Genet. 2016;48(5):510–518. doi: 10.1038/ng.3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li YR, Li J, Zhao SD, Bradfield JP, Mentch FD, Maggadottir SM, Hou C, Abrams DJ, Chang D, Gao F, et al. Meta-analysis of shared genetic architecture across ten pediatric autoimmune diseases. Nat Med. 2015;21(9):1018–1027. doi: 10.1038/nm.3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutierrez-Achury J, Zorro MM, Ricano-Ponce I, Zhernakova DV, Diogo D, Raychaudhuri S, Franke L, Trynka G, Wijmenga C, Zhernakova A. Functional implications of disease-specific variants in loci jointly associated with coeliac disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(1):180–190. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, Healey LA, Kaplan SR, Liang MH, Luthra HS, et al. The American rheumatism association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onengut-Gumuscu S, Chen WM, Burren O, Cooper NJ, Quinlan AR, Mychaleckyj JC, Farber E, Bonnie JK, Szpak M, Schofield E, et al. Fine mapping of type 1 diabetes susceptibility loci and evidence for colocalization of causal variants with lymphoid gene enhancers. Nat Genet. 2015;47(4):381–386. doi: 10.1038/ng.3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayes MD, Bossini-Castillo L, Gorlova O, Martin JE, Zhou X, Chen WV, Assassi S, Ying J, Tan FK, Arnett FC, et al. Immunochip analysis identifies multiple susceptibility loci for systemic sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94(1):47–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:7. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(6):e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, Korbel JO, Marchini JL, McCarthy S, McVean GA, Abecasis GR. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han B, Eskin E. Random-effects model aimed at discovering associations in meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(5):586–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedman ML, Reich D, Penney KL, McDonald GJ, Mignault AA, Patterson N, Gabriel SB, Topol EJ, Smoller JW, Pato CN, et al. Assessing the impact of population stratification on genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2004;36(4):388–393. doi: 10.1038/ng1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhattacharjee S, Rajaraman P, Jacobs KB, Wheeler WA, Melin BS, Hartge P, Yeager M, Chung CC, Chanock SJ, Chatterjee N. A subset-based approach improves power and interpretation for the combined analysis of genetic association studies of heterogeneous traits. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(5):821–835. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baurecht H, Hotze M, Rodriguez E, Manz J, Weidinger S, Cordell HJ, Augustin T, Strauch K. Compare and Contrast Meta Analysis (CCMA): a method for identification of pleiotropic loci in genome-wide association studies. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0154872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, Chen Y, Flicek P, Cunningham F. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP effect predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(16):2069–2070. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute for Systems Biology and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation–Wellcome Trust Diabetes and Inflammation Laboratory. ImmunoBase. 2013. http://www.immunobase.org

- 19.MacArthur J, Bowler E, Cerezo M, Gil L, Hall P, Hastings E, Junkins H, McMahon A, Milano A, Morales J, et al. The new NHGRI-EBI catalog of published genome-wide association studies (GWAS catalog) Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D896–D901. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pers TH, Karjalainen JM, Chan Y, Westra HJ, Wood AR, Yang J, Lui JC, Vedantam S, Gustafsson S, Esko T, et al. Biological interpretation of genome-wide association studies using predicted gene functions. Nat Commun. 2015;6:5890. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng PC, Henikoff SSIFT. Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D930–D934. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dozmorov MG, Cara LR, Giles CB, Wren JD. GenomeRunner web server: regulatory similarity and differences define the functional impact of SNP sets. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(15):2256–2263. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Roth A, Santos A, Tsafou KP, et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D447–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Vasaikar S, Shi Z, Greer M, Zhang B. WebGestalt 2017: a more comprehensive, powerful, flexible and interactive gene set enrichment analysis toolkit. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(W1):W130–W137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Law V, Knox C, Djoumbou Y, Jewison T, Guo AC, Liu Y, Maciejewski A, Arndt D, Wilson M, Neveu V, et al. DrugBank 4.0: shedding new light on drug metabolism. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D1091–D1097. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smyth DJ, Plagnol V, Walker NM, Cooper JD, Downes K, Yang JH, Howson JM, Stevens H, McManus R, Wijmenga C, et al. Shared and distinct genetic variants in type 1 diabetes and celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(26):2767–2777. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicolae DL, Gamazon E, Zhang W, Duan S, Dolan ME, Cox NJ. Trait-associated SNPs are more likely to be eQTLs: annotation to enhance discovery from GWAS. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(4):e1000888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ciofani M, Madar A, Galan C, Sellars M, Mace K, Pauli F, Agarwal A, Huang W, Parkhurst CN, Muratet M, et al. A validated regulatory network for Th17 cell specification. Cell. 2012;151(2):289–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Messina N, Fulford T, O'Reilly L, Loh WX, Motyer JM, Ellis D, McLean C, Naeem H, Lin A, Gugasyan R, et al. The NF-kappaB transcription factor RelA is required for the tolerogenic function of Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells. J Autoimmun. 2016;70:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kearney SJ, Delgado C, Eshleman EM, Hill KK, O'Connor BP, Lenz LL. Type I IFNs downregulate myeloid cell IFN-gamma receptor by inducing recruitment of an early growth response 3/NGFI-A binding protein 1 complex that silences ifngr1 transcription. J Immunol. 2013;191(6):3384–3392. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lumb JH, Li Q, Popov LM, Ding S, Keith MT, Merrill BD, Greenberg HB, Li JB, Carette JE. DDX6 represses aberrant activation of interferon-stimulated genes. Cell Rep. 2017;20(4):819–831. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dubois PC, Trynka G, Franke L, Hunt KA, Romanos J, Curtotti A, Zhernakova A, Heap GA, Adany R, Aromaa A, et al. Multiple common variants for celiac disease influencing immune gene expression. Nat Genet. 2010;42(4):295–302. doi: 10.1038/ng.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garner C, Ahn R, Ding YC, Steele L, Stoven S, Green PH, Fasano A, Murray JA, Neuhausen SL. Genome-wide association study of celiac disease in North America confirms FRMD4B as new celiac locus. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okada Y, Wu D, Trynka G, Raj T, Terao C, Ikari K, Kochi Y, Ohmura K, Suzuki A, Yoshida S, et al. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature. 2014;506(7488):376–381. doi: 10.1038/nature12873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hrdinka M, Horejsi V. PAG--a multipurpose transmembrane adaptor protein. Oncogene. 2014;33(41):4881–4892. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin JE, Broen JC, Carmona FD, Teruel M, Simeon CP, Vonk MC, van 't Slot R, Rodriguez-Rodriguez L, Vicente E, Fonollosa V, et al. Identification of CSK as a systemic sclerosis genetic risk factor through genome wide association study follow-up. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(12):2825–2835. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacob CO, Eisenstein M, Dinauer MC, Ming W, Liu Q, John S, Quismorio FP, Jr, Reiff A, Myones BL, Kaufman KM, et al. Lupus-associated causal mutation in neutrophil cytosolic factor 2 (NCF2) brings unique insights to the structure and function of NADPH oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(2):E59–E67. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113251108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrett JC, Clayton DG, Concannon P, Akolkar B, Cooper JD, Erlich HA, Julier C, Morahan G, Nerup J, Nierras C, et al. Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis find that over 40 loci affect risk of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2009;41(6):703–707. doi: 10.1038/ng.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Zuydam NR, Ahlqvist E, Sandholm N, Deshmukh H, Rayner NW, Abdalla M, Ladenvall C, Ziemek D, Fauman E, Robertson NR, et al. A genome-wide association study of diabetic kidney disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2018;67(7):1414–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Case/control datasets included in the study. Table S2. Loci reaching genome-wide level of significance in the subset-based meta-analysis and showing independent effect after linkage disequilibrium (LD)-clumping (r2 < 0.05 within 500 kB up- or downstream of the lead SNP). Table S4. Comparison of the results obtained with ASSET and CCMA for the 38 pleiotropic variants identified in our study. Table S5. Novel genome-wide associations for celiac disease, systemic sclerosis and type 1 diabetes (p value < 5 × 10–6 in the subset based meta-analysis and p value < 5 × 10–8 in each disease-specific meta-analysis). Table S7. Potential role of the lead polymorphisms (pleiotropic and single-disease associated variants), and their proxies (r2 ≥ 0.8) as expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) in whole blood, immune cell lines or tissues relevant for the diseases under study. Table S8. Specific cell types showing enrichment among regulatory DNA elements, Dnase 1 hypersensitivity sites and histone marks, and pleiotropic variants. (XLSX 77 kb)

Table S3. Results of the subset-based meta-analysis for the lead variants showing evidence of opposite allelic effect across the autoimmune diseases contributing to the association signal. Table S6. Coding variants in tight linkage disequilibrium (r2 ≥ 0.8) with lead non-coding polymorphisms according to the European population of the 1000 Genomes Project. Table S9. Transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) potentially disrupted by the set of pleiotropic variants. Table S10. Biological pathways significantly enriched among the set of common genes. Figure S1. Quantile–quantile plots for the p values of each individual disease, celiac disease (a), rheumatoid arthritis (b), systemic sclerosis (c), and type 1 diabetes (d), and the cross disease meta-analysis (e). Figure S2. Empirical −log10(P)-distribution of the Zmax statistic obtained by simulating 300 × 106 replicates of four normally distributed random variables. Figure S3. Manhattan plot of the subset-based meta-analysis of Immunochip data from celiac disease (CeD), systemic sclerosis (SSc), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and type 1 diabetes (T1D). Figure S4. Disease-specific odds ratio for the pleiotropic variants showing opposite allelic effects across autoimmune diseases. Figure S5. Regional association plots of the novel genome-wide associated locus for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), 2q32.3. Figure S6. Regional association plots of the novel genome-wide associated loci for systemic sclerosis (SSc), 11q23.3 (a), 1q25.1 (b), and 1q25.3 (c). Figure S7. Regional association plot of the novel genome-wide associated locus for celiac disease (CeD), 3p14.1. Figure S8. Regional association plot of the novel genome-wide associated locus for type 1 diabetes (T1D), 16p12.3. Members of the Coeliac Disease Immunochip Consortium, Members of the RACI, Members of the International Scleroderma Group, Members of the Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium (T1DGC). (PDF 1590 kb)

Summary statistics from the cross-disease meta-analysis using ASSET. (TXT 38863 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.