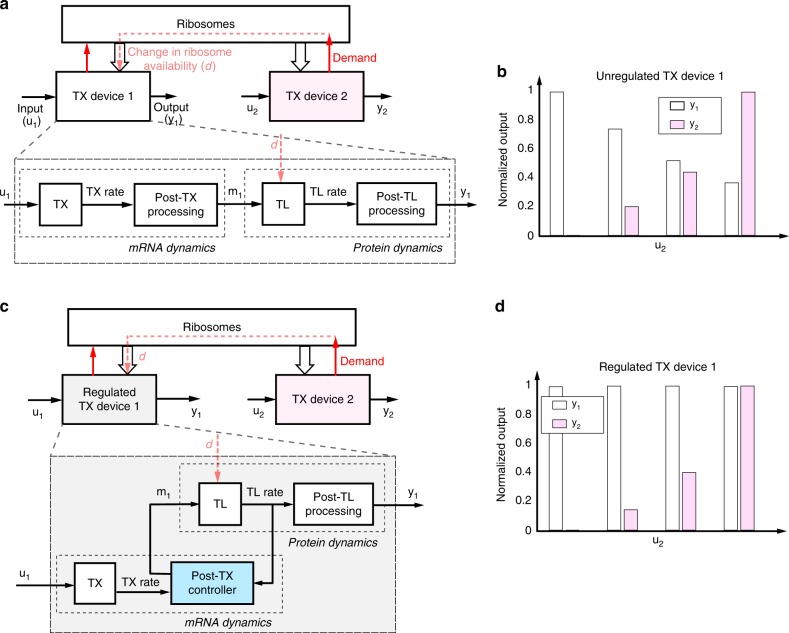

Fig. 1.

The problem of modularity in resource-limited genetic circuits. a Each TX device i (i = 1, 2) takes a TX regulator as input (ui) and produces a protein as output (yi). Each device can be decomposed into the cascade of key biological processes, here depicted as transcription (TX), post-TX mRNA processing, translation (TL), and post-TL protein processing. The TX (TL) block takes as input a TX regulator’s (mRNA) concentration and gives as output the TX (TL) rate. The post-TX (TL) mRNA (protein) processing block takes TX (TL) rate as input and produces mRNA (protein) concentration as output. These blocks can include processes affecting the stability of molecules (including dilution due to cell growth) or molecule activity (i.e., covalent modification). When multiple TX devices share a pool of limited ribosomes, the demand from one device causes a change d in ribosome availability, which affects TL in other devices, creating unintended interactions among TX devices. b Example behavior for the two-device circuit depicted in (a). The output from TX device 1 (y1) becomes coupled to the input to TX device 2 (u2), resulting in a circuit that lacks modularity. c Block diagram of an embedded post-TX feedback control design. A post-TX controller senses the TL rate of the GOI, takes as input the TX rate of the GOI, and, based on these two quantities, adjusts the mRNA level by post-TX mRNA processing in order to compensate for the effect of d. d The desired outcome from a regulated TX device is that despite TX device 2 is increasingly activated, the output of TX device 1 remains unchanged when presented with a constant input u1