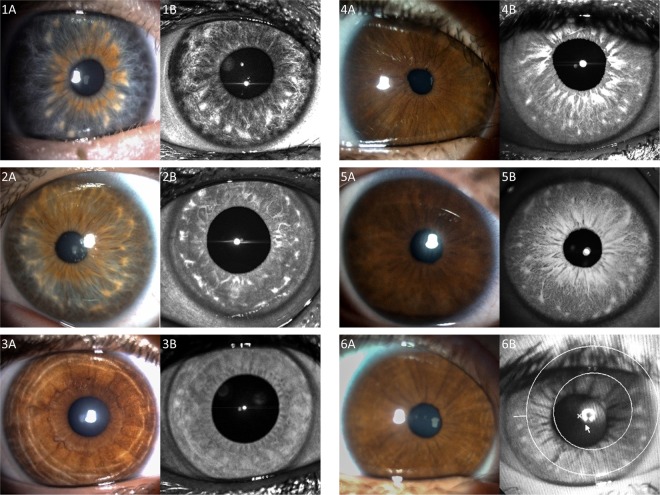

Figure 1.

Visibility of Brushfield spots and Wölfflin nodules under white (Column A), versus near-infrared (Column B) illumination. (1A) Brushfield spots and extensive iris thinning peripheral to these spots is seen with standard white light in a child with Down syndrome and blue irides. (1B) Same Brushfield spots noted with 820 nm wavelength near-infrared photography. (2A) Brushfield spots seen using white light in a patient with Down syndrome and hazel irides. (2B) Same Brushfield spots noted with 820 nm wavelength near-infrared photography. (3A) Standard white light iris photography fails to reveal any characteristic iris spots or nodules in a control. (3B) 820 nm wavelength near-infrared photography discloses Wölfflin nodules. (4A, 5A) In these brown-eyed children with Down syndrome, no Brushfield spots are apparent using standard visible white light. (4B,5B) In the same children, Brushfield spots appear when using 820 nm wavelength near-infrared light. one may also readily recognize here a paucity of iris contraction furrows in children with Down syndrome. (6A) Child with Down syndrome and brown irides with no apparent spots using standard visible white light. (6B) Brushfield spots in the same child become detectable using the fundus camera with a 650–735 nm wavelength barrier filter for near-infrared photography. Compared with the brown irides noted amongst most patient controls (3A) contraction furrows were lacking in the brown irides of children with Down syndrome (4A,5A) or were almost imperceptible (6A).