Abstract

Objectives

To examine the personal and social experiences of younger adults after stroke.

Design

Qualitative study design involving in-depth semi-structured interviews and rigorous qualitative descriptive analysis informed by social constructionism.

Participants

Nineteen younger stroke survivors aged 18 to 55 years at the time of their first-ever stroke.

Setting

Participants were recruited from urban and rural settings across Australia. Interviews took place in a clinic room of the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health (Melbourne, Australia), over an online conference platform or by telephone.

Results

Four main themes emerged from the discourses: (1) psycho-emotional experiences after young stroke; (2) losing pre-stroke life construct and relationships; (3) recovering and adapting after young stroke; and (4) invalidated by the old-age, physical concept of stroke. While these themes ran through the narratives of all participants, data analysis also drew out interesting variation between individual experiences.

Conclusions

For many younger adults, stroke is an unexpected and devastating life event that profoundly diverts their biography and presents complex and continued challenges to fulfilling age-normative roles. While adaptation, resilience and post-traumatic growth are common, this study suggests that more bespoke support is needed for younger adults after stroke. Increasing public awareness of young stroke is also important, as is increased research attention to this problem.

Keywords: stroke, young adult, middle aged, qualitative research, psychosocial aspects, patient-centred medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used qualitative methodology to improve understanding of the complex human experiences after young stroke.

A relatively large and diverse sample of younger stroke survivors participated.

A rigorous qualitative research design was used including consensus coding and recruitment to data saturation.

The study was performed within the specific context of Australia, hence the insights may not be transferable to other settings.

Introduction

Stroke is a major public health concern as a leading cause of acquired adult disability and death in Australia.1 Although it most often occurs in older age, the incidence of young stroke (18 to 65 years) is increasing worldwide.2 3 Improving understanding of younger adults’ experiences of stroke is therefore increasingly important for providing best-quality support to this group.

Quantitative young stroke research has found that around half of those experiencing stroke in younger age are unable to return to full-time employment and 5% require long-term institutionalised care.4 5 In a national Swedish study, more than half also reported being unsatisfied with life as a whole after young stroke.6 While quantitative studies measuring functional and quality of life outcomes in large samples of younger survivors have been informative, they have offered limited insight into the lived experience of stroke in younger age. Vanderford et al 7 (p. 14) described that patients are ‘active interpreters, managers, and creators of the meaning of their health and illness’. A social science approach using qualitative methodology is hence important for understanding the rich and complex meanings created within the young stroke experience.8

While qualitative studies with participants of all ages report frustrations post-stroke such as dependence and mental health challenges,9–11 there is limited primary qualitative research examining younger adults’ unique experiences of stroke.12 13 Qualitative studies to date have focused on specific cohorts, such as young women and couples,14–17 and specific parts of the young stroke experience, such as clinical care and changes to sense of self.15 18–20 Additional qualitative research is required to improve our understanding of the complex psychosocial experiences after young stroke.21 The present study aimed to contribute to the literature through in-depth qualitative examination of younger adults’ personal and social experiences of stroke from the tradition of social constructionism.

Social constructionism is a philosophy of knowledge that supports that reality is socially constructed and reified through language. Therefore, while medicine presents ‘disease’ as an objective biological product that is invariant in time and place, constructionism supports that ‘illness’ is the experience and meaning of the condition and defined within particular social and cultural systems.22 23 In the arena of qualitative research, constructionism also acknowledges that reality is shared in creation by researcher and participant within a specific context.24 Informed by this approach, the present study not only aimed to describe the thematised meanings in the discourses, but also aimed to draw out the variation, complexity and tactic meanings within the social construction of the young stroke experience.24–26

Methods

Design

Data for this study and a second study component (regarding participants’ experiences with healthcare services) were collected from a single in-depth semi-structured interview (see the questions relevant to this study in online supplement 1).

bmjopen-2018-023525supp001.pdf (59.6KB, pdf)

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Austin Health Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/16/Austin/451). Written informed consent was provided by all participants prior to participation. Anonymity was preserved by removing identifiable information from transcripts and referencing quotes by basic demographic data only.

Patient involvement

The topic guide was informed by a review of the young stroke literature and refined in discussion with two young stroke survivors known to the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health. The interview was also piloted with a third volunteer young stroke consumer of the Florey. As no changes were advised to the guide after piloting, this interview was also included for analysis with written informed consent from the interviewee. At completion of the study, all patients who contributed were provided with infographics summarising the study results.

Participant sampling

Participants were purposively sampled based on their location to ensure a national sample was recruited. Inclusion criteria were ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke at least two months prior, aged 18 to 55 years at the time of diagnosis, living in the community, English-speaking and cognitive ability to participate in an interview. Exclusion criteria were more than one prior diagnosis of stroke and significant comorbid disease. Participants were recruited from the Florey stroke research registry, Austin Hospital outpatient stroke clinic and community by means of research flyers, stroke organisation newsletters, social media advertisements and snowball sampling. Interested individuals initiated email or phone contact with the researchers, received the study information pack and organised an interview time with the first author.

Participant characteristics

There were 19 participants in total (see participant and interview characteristics in table 1). Participants were aged 19 to 54 years at diagnosis and ranged from 6 months to 24 years post-stroke. They reported wide-ranging stroke sequelae during the interviews (ie, prominent physical and/or cognitive impairments to mild or no identified residual effects), though no residual post-stroke aphasia. Support persons were also present in three interviews at the request of participants, but their contributions were not included for analysis.

Table 1.

Participant and interview characteristics

| Number | Gender | Age (years) | Time post-stroke | Age at stroke (years) | Type of stroke | State | Employment pre-stroke | Employment at interview | Civil status | Number of children | Private health insurance | Interview medium | Duration |

| 1 | F | 32 | 14 years | 19 | H | VIC | Studying | Self-employed (another field) | Relationship | 0 | Yes | Online | 1:52 |

| 2 | M | 39 | 6 years | 33 | I | WA | Employed | Employed (another field) | Divorced (post-stroke) | 0 | No | Telephone | 1:10 |

| 3 | M | 57 | 3 years | 54 | H | QLD | Employed | Employed | Divorced (pre-stroke) | 2 | Yes | Telephone | 1:35 |

| 4 | F | 46 | 6 months | 46 | I | NSW | Employed | Employed | Relationship | 0 | Yes | Telephone | 1:21 |

| 5 | M | 40 | 3 years | 37 | I | SA | Self-employed | Self-employed | Married | 2 | Yes | Telephone | 1:00 |

| 6 | M | 44 | 3.5 years | 41 | I | VIC | Employed | Unemployed | Married | 0 | No | In person | 1:56 |

| 7 | F | 47 | 15 years | 31 | I | QLD | Studying | Employed | Married | 2 | Yes | Telephone | 1:09 |

| 8 | M | 47 | 3.5 years | 44 | I | VIC | Employed | Unemployed | Married | 0 | No | Online | 1:36 |

| 9 | M | 43 | 3 years | 40 | I | SA | Employed | Unemployed | Married | 2 | Yes | Online | 1:38 |

| 10 | F | 42 | 4 years | 38 | I | SA | Employed | Employed | De facto | 3 | Yes | Telephone | 1:13 |

| 11 | F | 48 | 4 years | 44 | I | VIC | Employed | Employed | Married | 2 | Yes | In person | 1:27 |

| 12 | F | 29 | 7 years | 22 | H | NSW | Employed | Employed | Relationship | 0 | Yes | Telephone | 1:37 |

| 13 | M | 34 | 1.5 years | 33 | H | VIC | Unemployed | Unemployed | De facto | 0 | No | In person | 1:00 |

| 14 | M | 33 | 3 years | 30 | I | VIC | Employed | Employed | Married | 0 | No | In person | 0:43 |

| 15 | F | 52 | 1 year | 51 | I | WA | Employed | Employed | Married | 3 | Yes | Online | 1:15 |

| 16 | M | 49 | 1 year | 48 | I | QLD | Employed | Studying | Divorced (pre-stroke) | 2 | No | Online | 0:51 |

| 17 | F | 36 | 1 year | 35 | I | VIC | Employed | Unemployed | Married | 1 | Yes | Online | 1:14 |

| 18 | F | 46 | 24 years | 22 | I | VIC | Employed | Employed (another field) | Married | 3 | Yes | Online | 1:29 |

| 19 | F | 30 | 3.5 years | 26 | H | VIC | Employed | Studying | De facto | 0 | No | In person | 1:35 |

F, female; H, haemorrhagic; I, ischaemic; M, male; NSW, New South Wales; QLD, Queensland; SA, South Australia; VIC, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

Setting

Participants were recruited from urban and rural settings across Australia. Interviews took place face-to-face in a private setting in a clinic room of the Florey (Melbourne, Australia), over an online conference platform or by telephone.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted by the first author between February and May 2017. The first author was a final-year graduate medical student with an interest in patient-centred medicine. She had no established relationship with any of the participants prior to the study. After the interviews, three participants submitted additional written reflections, which were also subject to analysis.

Analysis

The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim by the first author and analysed with NVivo 11 software using a rigorous qualitative descriptive approach informed by social constructionism.26 Rigour was increased through independent consensus coding by two authors and discussion of divergent interpretations with a third author when required. Analysis proceeded through phases that were repeated several times to data saturation (ie, when no new themes or sub-themes emerged from the final three interviews): (1) codes were inductively ascribed to small segments of meaning within the data, indexed with operational definitions in a codebook and iteratively revised with rereading and cross-comparison of transcripts; (2) thematic relationships between codes, or axial codes, were derived with memoing and concept mapping; and (3) the codes were organised into a hierarchical tree structure with rich themes and sub-themes. The present paper extracts the themes related to the personal and social experiences of participants.

Results

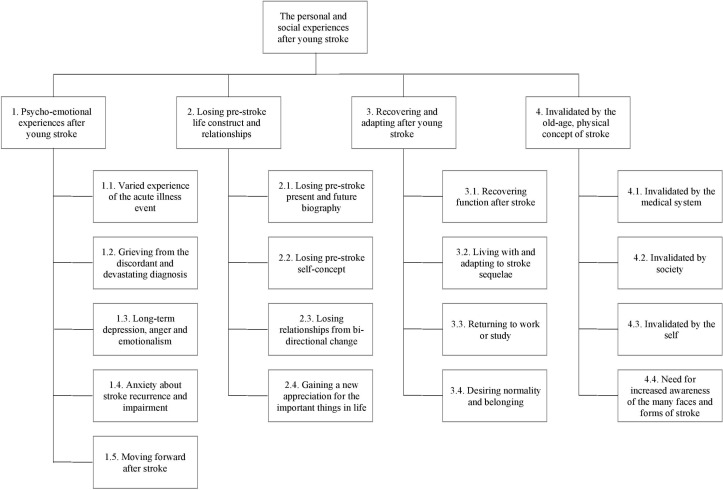

Four main themes and several sub-themes emerged from the discourses (see the thematic model in figure 1). While these themes ran through the narratives of all participants, data analysis also drew out interesting variation between individual experiences. Additional thematised quotations are available in the online supporting dataset.

Figure 1.

Thematic model.

Psycho-emotional experiences after young stroke

Varied experience of the acute illness event

Many participants understood the acute presentation of stroke to be ‘the facial droop, the arm paralysis or the speech problems’ (P7). Some said ‘that was exactly me’, but many described a more ambiguous scenario, such as ‘I can’t type and I’m feeling a bit fuzzy, but I can still cook my dinner and shower’, which made them less likely to seek emergency medical attention (P1 and P4). Psycho-emotional experiences of the acute stroke event also varied among participants, ranging from traumatic to even positive. One man described his distressing experience of being wheeled into the emergency department in a wheelchair: ‘I couldn’t control my head… and I could hardly find the strength to breathe in my lungs and I lost my vision… but I was fully awake inside… thinking… “I’m dying”’ (P2). In contrast, another participant said, ‘it was really pleasant… There was no lead up at all… and then all of a sudden I just felt… pleasantly weird’ (P9).

Grieving from the discordant and devastating diagnosis

After participants were diagnosed with stroke, many described going through states of grief including shock, denial, anger and depressed mood. The initial response was oftentimes ‘disbelief and stress and rejection’ because stroke was perceived as a disease of old age and unhealthy lifestyle factors and therefore incompatible with being a young, healthy adult (P1). One participant described that ‘stroke was always kind of marketed… for old people’ and many spoke of having ‘virtually no risk factors’ such as smoking, drinking, drug-taking, high blood pressure or heart disease (P19 and P3). After the shock of the ‘surreal’ diagnosis, many participants described feeling angry and crying frequently (P10). They were ‘grieving [their] physical ability’ and ‘grieving the person [they were] because everything had changed’ (P19 and P12). Several also spoke of questioning ‘why me’ and ‘why God’; they were faced with existential and spiritual questioning of an unfair and incoherent event in young age (P1 and P2).

I experienced a few years of almost rage. I’d go through “why me” and “how come” and all those phrases and I’d just been so angry inside myself. (P1)

While stroke caused grief for many, some individuals’ reactions were mitigated by their personal and/or family history. One woman with long-term high cholesterol and a family history of stroke spoke of ‘always expecting to have a stroke at some point’ (P15). Another participant related how the diagnosis was ‘almost a good result’:

I was absolutely astounded because I was sitting there waiting to be told I had a brain tumour… And so in some ways… it was actually almost a good result. (P11)

Long-term depression, anger and emotionalism

For some participants, depressive symptoms after stroke were short term and reactive (grief, <6 months). Others, however, developed long-term and unremitting depression. Several participants also described long-term ‘anger management issues’ and related how they would unintentionally take their temper out on partners, parents and children (P7). One man described that ‘when you have the slightest problem the feeling inside you is like an atomic bomb and you just can’t keep it in sometimes’ (P2). Some participants also described becoming ‘a lot more emotional’ after stroke (P13). They would cry more easily than previously and one participant considered, ‘I don’t know whether it’s a chemical brain thing or whether just a fact that I’ve gone through something really bad’ (P12).

Anxiety about stroke recurrence and impairment

Anxiety was another prominent psycho-emotional experience of participants, especially regarding stroke recurrence. For some participants, this was made worse by not having a cause for their stroke and the belief that there is ‘nothing I can do to stop it’ (P13). Several participants were ‘dominated’ by the fear that a subsequent stroke would render them more impaired and dependent and many lived with chronic uncertainty about the future (P7).

I get anxiety all the time now… Even if I feel anything, like a ringing in the ear, then I get paranoid. (P14)

Anxiety about stroke impairments was also reported by many participants, including anxiety about lacking control over one’s body, falling over in public and not performing tasks properly because of cognitive impairment.

Moving forward after stroke

For many participants, it took years to come to terms with the stroke diagnosis. Time itself was identified as one important mitigating factor to ‘detrimental’ thinking (P4). One participant described, ‘I think about it every day obviously, but I’m not thinking about it as detrimentally as before. It’s more in the past now’ (P4). Participants also described using different mechanisms to cope with what had happened, including focusing on the way forward, occupying the mind and setting goals. One participant described, ‘I had this idea that if I stopped depression would just consume me… so I had this idea that I… would have my runners on and just work and… socialise and see how far I get’ (P12). Humour was also used as a coping mechanism ‘because if you don’t laugh about it, you just cry’ (P17).

Losing pre-stroke life construct and relationships

Losing pre-stroke present and future biography

Many participants described stroke as causing profound loss. Largely, reflections were on ‘life losses’ and how participants had lost their established pre-stroke life construct, including work or study, family roles, leisure activities and social routines. Some also reflected on loss of future potential, from pursuing a career in journalism to snorkelling in the Great Barrier Reef. One man spoke of how he and his wife had ‘done those hard young years’ and had been looking forward to more senior positions at work, financial freedom and travel:

There [were] big steps to be had and that was just taken away. And you spent 20 years working towards that and then all of a sudden… it just gets cut off. (P9)

Participants confronted these losses at different times. For many, they became evident on returning home to the pre-stroke environment or witnessing friends ‘doing things that you can’t do’ on social media or otherwise (P17). One young woman described what it was like returning home after stroke:

I think what… really dawned on me was that fact that I’d been away for about three months now, my life was completely changed and myself included and nothing had changed at home at all… I remember seeing my work clothes just sprawled out on my bed like it was just the day before the stroke… And I remember patting my cat and I couldn’t pat her with both hands and I got really upset so I broke down for the first time. (P12)

Losing pre-stroke self-concept

Some participants also described losing their sense of self through stroke. At the extreme end, two participants described that they had in some way ‘died’ (P7 and P19). Another participant clearly delineated herself into the pre-stroke and post-stroke person and described the internal tension between her divided self-concepts: ‘the pre-stroke person will sort of just be beating up the post-stroke person because you know it’s like “why can’t you do it?”’ (P10). Other participants spoke of a same-but-different dichotomy with one articulating:

My core values and everything are all still the same… But I just feel different… I just view the world completely differently now. (P19)

More impaired participants also spoke of trying to define themselves within the disability discourse post-stroke. Some described themselves as disabled, while others dissociated from disability language with one relating, ‘I just consider myself… really badly injured’ (P16). One woman described how she was left with an ambiguous self-definition:

Disabled is not a bad word… [But] I can’t think of another word to describe myself… because I’ll say you know to family… “oh I’m disabled” and someone will say “you’re not disabled”. And I’m like “but I am I suppose”… I don’t know what I am. (P19)

Losing relationships from bidirectional change

Adding to these losses, many participants recounted breakdown of relationships and social isolation after stroke. The most prominent contributor to this was loss of friendships. Participants reasoned that their friends did not know how to approach the situation, visiting required too much effort, they were no longer able to connect over shared social activities such as running and there was loss of the balance needed to maintain a reciprocal friendship. Some participants also experienced breakdown of intimate and family relationships with one participant describing, ‘I lost my wife and my home life… and that was taken away from me because she couldn’t live that way anymore’ (P2). Loss of relationships had a significant impact on the lives of many participants and one young woman described how her ‘friendships and the distress within that was actually even bigger than having had a stroke’ (P12). Another participant described the isolation:

When I had the stroke and came home… nobody came… I was that desperate to talk to people, and I know it sounds awful this, but I got a knock on the door by Jehovah’s Witnesses and I invited them in for a cup of tea and a chat because they were the only people that came. (P2)

Participants also acted to isolate themselves after stroke, hence the bidirectionality of relational loss. They isolated themselves in order to focus on their recovery and spend time with family and some internalised their thoughts and emotions so as not to ‘further burden’ and ‘add to the pain’ of others (P12). Some also experienced that their stroke impairments isolated them; they became ‘an observer’ or ‘spectator’ because they were no longer able to participate in interactions or activities in the way they previously had (P16 and P17).

Gaining a new appreciation for the important things in life

The losses of stroke also saw participants experience gains. They gained a new appreciation of ‘what’s actually important in my life’ (eg, family), they were more mindful of how they used their time (eg, on things that ‘spark joy’), they were less self-centred and they were more attuned to nature (P10 and P19). In accord with this, some also described strengthened relationships with partners and family members after the stroke.

I don’t think there’s any other way to describe it other than it’s a great sense of loss, but at the same time you gain a second chance, a second chance to do things differently and approach life differently. (P17)

Recovering and adapting after young stroke

Recovering function after stroke

Participants with physical and/or cognitive effects of stroke described that it often took weeks to months before they began making marked gains in function and recovery was often experienced as a mechanical stepwise process. For example, one participant who had locked-in syndrome after their stroke spoke of going from getting their ‘quads engaging, flickering’ to eventually being able to walk (P2). Another participant reflecting on the process of regaining speech described two years of ‘stringing sounds together to make small, to longer, to multi-syllabic words’ (P17). However, the initial period of relatively rapid physical recovery set several participants up with the ‘false expectation’ that ‘progress would just continue’ (P10 and P16). It was then very difficult for participants when they perceived that their recovery slowed, halted or even reversed because of the emergence of late complications (eg, spasticity). For most participants though, recovery was ultimately regarded as an ongoing and long-term process ‘if not… a fact of life after stroke’ (P12).

[Recovery] does plateau a bit… I will say that most of my recovery happened in the first couple of years, but I’m 15 or 16 years post-stroke now and I still notice changes this year compared with last year. (P7)

Living with and adapting to stroke sequelae

As part of their recovery, participants were faced with finding ways to live with and adapt to any persisting stroke sequelae (eg, fatigue, memory problems, sensory overstimulation and weakness). One of the most challenging effects was post-stroke fatigue. Participants reported that it was largely caused by mental stimuli such as learning or concentrating and was best managed by ‘turning off the brain’ (P13). Participants also modified their tasks and routines to accommodate fatigue. For example, one completed important work-related tasks in the morning to mitigate mistakes from fatigue and another managed by resting days prior to and after an important event. One participant described post-stroke fatigue:

It’s almost like you were hit by a bus. It’s almost like you’re coming down with the flu. You can sleep for 10 hours and you still feel like rubbish. (P12)

Returning to work or study

For many participants, returning to work or study was an important part of recovering from stroke as a source of purpose in life, contribution to society and rehabilitation. One participant without work after stroke described how ‘that’s the hardest part… not having a job… having that purpose’ (P8). Another related, ‘the rest of your life is in front of you [and] I’m now a burden to the economy’ (P6). Interestingly, work was also an important part of fitting into younger circles and having something to talk about:

You kind of feel like you have nothing to talk about other than the stroke… Even with my husband, I feel like he comes home, has a lot of stories to tell, and I just have what I’ve done today in rehab. (P17)

However, while work was identified as important for many participants, some described that it was less meaningful post-stroke because of changed priorities. Some also attributed work-related stress to causing their stroke, which further shaped the meaning after the illness event.

Desiring normality and belonging

Many participants expressed that they ‘just wanted to feel normal again’ and ‘just wanted to belong’ after stroke (P11 and P18). They particularly spoke of the value of being spoken to as a normal person. One participant explained that when everyone says ‘“oh can I open the door for you”… it just… reminds you that you’re different’ (P8). Adaptive devices also symbolised abnormality:

There’s a lot of things out there that make it easier, but you just want to feel normal… I need… transcribing software and… a special desk and… a special parking space… a special everything. (P17)

While many participants actively sought to fit in and conceal their difficulties, one young woman described reaching a point of rejecting this approach. She described, ‘I just got to the point where I’m just like I shouldn’t have to hide [my leg brace]. I need it’ (P19).

Invalidated by the old-age, physical concept of stroke

Invalidated by the medical system

Invalidation describes the experience of being dismissed, discredited or devalued and emerged as a common theme in participants’ discourses. One early source of this was the medical system. On initial presentation to the emergency department, many participants described that their condition was dismissed as drug or alcohol related. Some also related that stroke was explicitly dismissed as a diagnosis because of their younger age. One participant who presented to the emergency department numerous times before being diagnosed with stroke described:

Being 46, people still classified that as… too young to have a stroke. That was said to me a few times and that was quite dismissive. (P4)

Invalidated by society

Invalidation was also commonly experienced at the social–illness interface. A discrediting social experience reported by many participants was encountering shock and disbelief in others when they disclosed their stroke diagnosis. One man described, ‘I actually had an argument with someone because they refused to believe that I had had a stroke… [exclaiming] “you’re just too young, that’s stupid, that’s ridiculous”’ (P8). They also experienced frustration and distress because of the assumption that it must have been caused by smoking, drinking, drug-taking or stress. One woman described, ‘they sort of look at you like, “oh were you on drugs… or are you a smoker?”’ (P17). Another participant with an arteriovenous malformation as the cause of her stroke related:

It used to really upset me because having a stroke I didn’t do anything to myself… Stroke just happened. (P19)

Another strikingly common experience of participants was feeling discredited in social interactions when others expressed that they were ‘lucky’ or ‘fine’ (P3 and P13). This caused hurt and frustration for participants because it negated the substantial impact stroke had had on their lives and made their cognitive and psycho-emotional difficulties seem fabricated.

It actually hurts when people say “you got out of it okay”… because… they can’t feel what I feel. (P5)

In the midst of these invalidating social experiences, several participants described young stroke groups as a unique source of understanding and sensitivity. One woman described how a stroke survivor does not say ‘‘‘gee you look great, I can’t even tell you’ve had a stroke”, which is what everyone else says and… makes you feel like you’re making up your symptoms’, but rather ‘they automatically understand that it’s a huge thing that’s happened, especially when you’re young, and they just give you comfort and support’ (P7). However, validation through support groups was not a universal experience. One man with debilitating but invisible cognitive disability described being ‘out of place’ everywhere after stroke including in ‘the brain injury crowd’ because ‘even they look at me [and] some of them go, “why are you here mate?”’ (P9).

Invalidated by the self

Some participants also demonstrated internal or self-driven invalidation. For example, some reported lower self-worth and embarrassment as a result of no longer fitting into the normate. One woman related, ‘I’m really battling feeling embarrassed and… self-conscious because you’re not walking like a normal person’ (P17). Another aspect of self-invalidation was internalising the ‘fraud’ and ‘stigma’ associated with invisible disability in society (P9). One man with debilitating neurological fatigue described, ‘I feel like a fraud every day because it’s an invisible thing’, and another related, ‘if I’m tired and I have a nap, like I feel like guilty or something… You feel like fatigue is just an excuse’ (P9 and P19).

Need for increased awareness of the many faces and forms of stroke

In response to these invalidating experiences, many participants described the need for increased awareness of the many faces and forms of stroke. One man described that ‘the word stroke is a very small word but stroke itself is a huge thing; there are so many permutations, so many’ (P3). Another emphasised that ‘stroke happens to anyone of any age’ including ‘children, babies, grandmas, male, female, overweight, healthy, fit’. This individual also articulated that her illness experience would have been profoundly different if there was awareness of stroke in young healthy adults:

I wouldn’t have to be embarrassed or ashamed or have to justify who I am or what has happened to me. I’d feel like people wouldn’t be so shocked when they see a young person with a walking cane and assume that it’s just a sports injury… I used to think that I wished I had breast cancer instead of had a stroke because then I would feel more accepted and… understood… Very much like cancer, [stroke] doesn’t discriminate, but we all know kids have cancer. (P19)

Discussion

The present study contributes novel and nuanced insights to the understanding of younger adults’ personal and social experiences after stroke. It highlights common themes in participants’ reflections, as well as interesting variation between individual narratives. The practical implications regarding shortfalls in current support options after young stroke are outlined in the following discussion.

The first prominent theme of this research was the psycho-emotional experiences of younger stroke survivors. While there was marked variation in emotional experiences of the acute illness event, the responses that followed predominantly spanned grief, depression, anger, emotionalism and anxiety. The grief response was strongly related to participants perceiving stroke as an unfair and discordant diagnosis in the context of younger age and reasonable health, which is consistent with prior research.13 15 17 Depression, anger management issues, emotional lability and anxiety were also commonly experienced and often endured for many years after the illness event. These findings support the need for early and ongoing access to psychological care after young stroke, as well as support for partners, children and parents because of the impact of these reactions and changes on those in the stroke survivor’s close environment. The need for psychological care oriented at survivors and couples after stroke affirms existing recommendations, though access to these services appears limited.16 21 27 28

Many of the younger stroke survivors also experienced multifold losses after stroke, including loss of pre-stroke vocation, leisure activities, social groups and self-concept. Loss of self-concept was compounded by participants having to navigate disability language after young stroke, which contributes further insights to the existing literature.29 This theme suggests that life losses may be meaningful targets for post-stroke rehabilitation, ie, working to recreate one’s life construct, social system and sense of self.30 Importantly, many participants also described that strengthened appreciations and personal growth after stroke helped them through these losses. Adaptation to disability may therefore be helped by a rehabilitation approach incorporating positive psychology constructs (eg, optimism, hope, resilience, benefit finding, meaning making and post-traumatic growth), which aligns with evidence-based recommendations.31

Another important point of reflection for participants was the process of recovering and adapting after stroke. Many described their recovery trajectory as involving an initial period of latency, followed by months to years of stepwise improvement, and then slowed but continued progress (including functional improvement and/or adaptation). This differs from the short-term model of post-stroke rehabilitation grounded in the concept of stroke recovery as short term with definitive plateauing and suggests that recovery may be augmented by longer-term rehabilitation and clinical support than is presently offered.13 This study also suggests that it may be beneficial to provide increased support during particularly distressing periods, including when recovery is perceived to be slowing, ceasing or reversing due to late complications (eg, spasticity). In addition to functional gains, returning to work or study and regaining a sense of normality were also identified as key recovery priorities for participants, which affirms the importance of vocational rehabilitation in young stroke care.32 33

Invalidation—or being dismissed, discredited or devalued after young stroke—was a novel theme that emerged from this research. It primarily manifested in participants being met with shock and rejection when they disclosed their diagnosis, presumptions about the cause of their stroke and dismissal of their invisible impairments. These invalidating experiences were strikingly common among the younger stroke survivors and largely driven by the socially embedded understanding of stroke as a disease of old age, unhealthy lifestyle choices and physical disability. This builds on the literature finding of isolation and frustration after young stroke as a result of invisible sequelae being overlooked by others.16 19 Adding to external invalidation, participants also demonstrated self-invalidation including reduced self-worth after acquiring disability and discrediting of their own invisible impairments as potentially fabricated or exaggerated. This is consistent with the concept of ‘internalised oppression’ and occurs when an impaired person internalises prejudiced views about disability.34 Public education about young stroke and the non-visible effects of brain injury may offer an opportunity to address these issues. Also, these findings again raise the need to incorporate positive psychology and resilience-building strategies into rehabilitation for young stroke survivors.31

While younger adults experience many of the same functional and psychosocial consequences of stroke as older people, some important effects appear to be age specific. For example, all-age studies report challenges to mental well-being and social participation after stroke.10 11 However, consequences of stroke that are either unique or heightened in younger populations include difficulties fulfilling roles specific to young age and feeling invalidated by the old-age concept of stroke.

In some ways, young stroke is also similar to other life-changing events experienced in young age, such as being diagnosed with cancer or having a motor vehicle accident. A meta-synthesis of qualitative young cancer literature identified comparable experiences of change to one’s sense of self, confrontation with mortality, disruption to developmental needs, existential questioning, changes in relational dynamics and strengthened appreciations.35 However, unique to young stroke is the acquisition of physical, cognitive and/or affective impairment, the need to define oneself within the confines of disability language, the invalidation from the social construct of stroke and the continued lack of awareness of the occurrence in younger age. A number of the negative aspects of the young stroke experience are direct products of the social concept of stroke and may therefore be amendable to change through raising of awareness.

A strength of this research is the diversity of the study sample: participants were from varying urban and rural settings across Australia, had varied pre-stroke vocational and family circumstances, were at various time points post-stroke and had wide-ranging stroke sequelae. Additional strengths include data saturation and adjudication of the analysis through consensus coding.

A limitation of the study is that it was performed within the specific context of Australia, hence the insights may not be transferable to other settings. Furthermore, the strategy of using online and telephone interview platforms to include participants living at a distance may have influenced participant disclosure, though the researchers were reassured by the consistent openness and depth of the reflections. The authors also acknowledge that there were no participants with residual post-stroke aphasia, which may been a result of the recruitment or interviewing methods. Future studies could adopt strategies to better include participants with language impairment, eg, explicitly inviting those with language difficulties in the recruitment material and using supportive communication strategies in the interviewing process.

Future research is required on methods of increasing awareness of young stroke in society. Research should also explore rehabilitation and community support approaches that better prepare young stroke survivors for the challenges they will encounter.

Conclusion

Young stroke is not a single phenomenon; ‘there are so many permutations’. For many younger adults though, stroke is an unexpected and devastating life event that profoundly diverts their biography and presents complex and continued challenges to fulfilling age-normative roles. While adaptation, resilience and post-traumatic growth are common, this study suggests that more bespoke support is needed for younger adults after stroke. Increasing public awareness of young stroke is also important, as is increased research attention to this problem. Future research should explore rehabilitation and community support approaches that better prepare younger stroke survivors for the challenges they will encounter.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the patient advisers for their contribution to the study design, the study participants for sharing their personal experiences and the staff at the Florey and Austin Hospital for their support of this research. The Florey acknowledges the infrastructure support of the Victorian State Government.

Footnotes

Contributors: JS and JB conceived of the study and all authors contributed to the study design. JS collected the data and performed data analysis and interpretation. JB also analysed the complete dataset and JL provided input regarding analysis and interpretation. JS was the primary writer of the manuscript, but JB, JL and VT also contributed to the writing and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors provided final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: JB was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Established Research Fellowship (grant number N1058635). This research received no other specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Austin Health Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/16/Austin/451).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.3181p74.

References

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health 2014 [Internet]. Australia’s health series no. 14. Cat. no. AUS 178. Canberra: AIHW 2014. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129547205 (cited 10 Feb 2017).

- 2. National Stroke Foundation (AU). Young stroke 2015 [Internet]. Melbourne: NSF 2015. https://strokefoundation.org.au/news/2015/07/14/young-stroke-2015 (cited 1 May 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Béjot Y, Delpont B, Giroud M. Rising stroke incidence in young adults: more epidemiological evidence, more questions to be answered. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e003661 10.1161/JAHA.116.003661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glozier N, Hackett ML, Parag V, et al. . The influence of psychiatric morbidity on return to paid work after stroke in younger adults: the Auckland Regional Community Stroke (ARCOS) Study, 2002 to 2003. Stroke 2008;39:1526–32. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.503219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Teasell RW, McRae MP, Finestone HM. Social issues in the rehabilitation of younger stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:205–9. 10.1016/S0003-9993(00)90142-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roding J. Stroke in the younger: self-reported impact on work situation, cognitive function, physical function and life satisfaction - a national survey [PhD dissertation]. Umeå: Umeå University, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vanderford ML, Jenks EB, Sharf BF. Exploring patients’ experiences as a primary source of meaning. Health Commun 1997;9:13–26. 10.1207/s15327027hc0901_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Conrad P. The experience of illness: recent and new directions: In Research in the Sociology of Health Care, 1987;6:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Luker J, Lynch E, Bernhardsson S, et al. . Stroke survivors’ experiences of physical rehabilitation: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96:1698–708. 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morris JH, Oliver T, Kroll T, et al. . From physical and functional to continuity with pre-stroke self and participation in valued activities: a qualitative exploration of stroke survivors’, carers’ and physiotherapists’ perceptions of physical activity after stroke. Disabil Rehabil 2015;37:64–77. 10.3109/09638288.2014.907828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sarre S, Redlich C, Tinker A, et al. . A systematic review of qualitative studies on adjusting after stroke: lessons for the study of resilience. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:716–26. 10.3109/09638288.2013.814724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Immenschuh U. “My arm and leg - they are just sleeping” Perspectives of younger people on their experiences of having a stroke [PhD dissertation]. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kuluski K, Dow C, Locock L, et al. . Life interrupted and life regained? Coping with stroke at a young age. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2014;9:22252 10.3402/qhw.v9.22252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stone SD. Reactions to invisible disability: the experiences of young women survivors of hemorrhagic stroke. Disabil Rehabil 2005;27:293–304. 10.1080/09638280400008990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leahy DM, Desmond D, Coughlan T, et al. . Stroke in young women: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. J Health Psychol 2016;21:669–78. 10.1177/1359105314535125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Banks P, Pearson C. Parallel lives: Younger stroke survivors and their partners coping with crisis. Sexual and Relationship Therapy 2004;19:413–29. 10.1080/14681990412331298009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quinn K, Murray CD, Malone C. The experience of couples when one partner has a stroke at a young age: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:1670–8. 10.3109/09638288.2013.866699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wolfenden B, Grace M. Identity continuity in the face of biographical disruption: ‘It’s the same me’. Brain Impairment 2012;13:203–11. 10.1017/BrImp.2012.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Röding J, Lindström B, Malm J, et al. . Frustrated and invisible-younger stroke patients’ experiences of the rehabilitation process. Disabil Rehabil 2003;25:867–74. 10.1080/0963828031000122276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bendz M. The first year of rehabilitation after a stroke - from two perspectives. Scand J Caring Sci 2003;17:215–22. 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2003.00217.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lawrence M. Young adults’ experience of stroke: a qualitative review of the literature. Br J Nurs 2010;19:241–8. 10.12968/bjon.2010.19.4.46787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Conrad P, Barker KK. The social construction of illness: key insights and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav 2010;51 Suppl:S67–S79. 10.1177/0022146510383495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eisenberg L. Disease and illness. Distinctions between professional and popular ideas of sickness. Cult Med Psychiatry 1977;1:9–23. 10.1007/BF00114808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Charmaz K. Grounded theory: objectivist and contructivist methods : Denzin NK, Lincoln Y, The handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jonassen DH. Technology as cognitive tools: learners as designers. In: ITForum Paper #1 [Internet]. 1994. (cited 1 Jun 2017).

- 26. Charmaz K. Constructionism and the grounded theory method : Holstein JA, Gubrium JF, Handbook of constructionist research. New York: The Guilford Press, 2008:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wolfenden B, Grace M. Vulnerability and post-stroke experiences of working-age survivors during recovery. Sage Open 2015;5:215824401561287 10.1177/2158244015612877 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berry M, Perez R, Young E, et al. . Assessing need for couples post-stroke: negative and positive factors associated with relationship satisfaction. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017;98:e35 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.08.108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hutton L, Ownsworth T. A qualitative investigation of sense of self and continuity in younger adults with stroke. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2017. 1–16. 10.1080/09602011.2017.1292922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ellis-Hill C, Payne S, Ward C. Using stroke to explore the life thread model: an alternative approach to understanding rehabilitation following an acquired disability. Disabil Rehabil 2008;30:150–9. 10.1080/09638280701195462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Martz E, Livneh H. Psychosocial adaptation to disability within the context of positive psychology: findings from the literature. J Occup Rehabil 2016;26:4–12. 10.1007/s10926-015-9598-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Medin J, Barajas J, Ekberg K. Stroke patients’ experiences of return to work. Disabil Rehabil 2006;28:1051–60. 10.1080/09638280500494819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vestling M, Ramel E, Iwarsson S. Thoughts and experiences from returning to work after stroke. Work 2013;45:201–11. 10.3233/WOR-121554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reeve D. Towards a psychology of disability: the emotional effects of living in a disabling society : Goodley D, Lawthron R, Disability and psychology: critical introductions and reflections. London: Palgrave, 2006:94–107. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim B, White K, Patterson P. Understanding the experiences of adolescents and young adults with cancer: a meta-synthesis. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2016;24:39–53. 10.1016/j.ejon.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023525supp001.pdf (59.6KB, pdf)