Macrophages are classified as proinflammatory M1 (classically activated) or anti-inflammatory M2 (alternatively activated),1 but binary classification fails to distinguish macrophage expression profiles.2 Tissue resident muscularis macrophages (MMs) in the gut muscularis externa modulate gut homeostasis including neuromuscular function.3, 4 Through neuroimmune cross-talk, MMs may sense cues in the microenvironment from the microbiota or extrinsic sympathetic neurons and relay this information to enteric neurons.3, 4 We showed that aging shifts the phenotype of MMs from an M2 to an M1 polarization state, which is associated with chronic, low-grade inflammation in the enteric nervous system and delayed intestinal transit.5 The objective of this study was to evaluate whether alterations in gut microbiota contribute to age-related changes in MMs and gastrointestinal dysmotility.

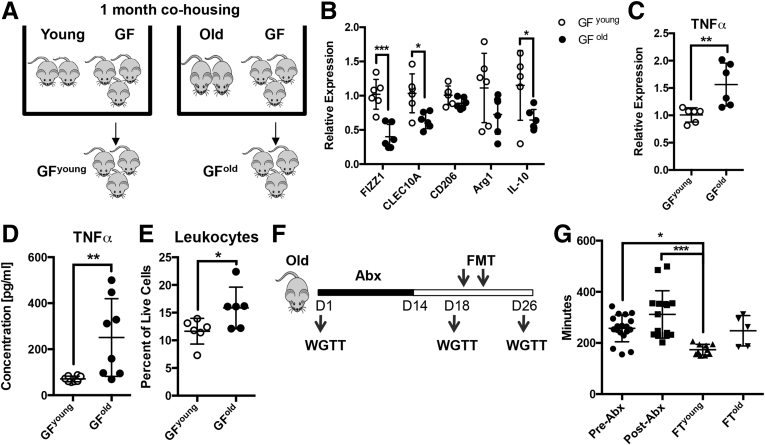

To determine the effect of microbiota on MM phenotype, germ-free (GF) mice were colonized by co-housing with young (age, 2 mo) or old (age, 24 mo) mice (Figure 1A).6 After 4 weeks, MMs were sorted from the colonized GF mice, termed GFyoung or GFold, and analyzed for RNA expression. MMs from GFold mice showed decreased expression of anti-inflammatory M2 markers, particularly found in inflammatory zone 1, C-type lectin domain family 10 member A, and interleukin 10 (Figure 1B), and increased expression of the proinflammatory M1 marker tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) (Figure 1C). Increased TNFα also was detected in protein extract of muscularis externa (Figure 1D), which mirrors recent studies showing higher TNFα levels in plasma6 and in ileum7 of GF mice colonized with old mice microbiota. We also found increased leukocyte infiltration in the muscularis of GFold mice (Figure 1E), suggesting that factors in the old microbiota drives inflammation.

Figure 1.

Microbiota from old mice alters macrophage phenotype and causes delayed intestinal transit. (A) GF mice were co-housed with either young or old mice for 1 month before expression analysis was performed on sorted MMs. MMs from GFold mice showed reduced expression of anti-inflammatory M2 markers, particularly found in inflammatory zone 1 (FIZZ1), C-type lectin domain family 10 member A (CLEC10A), and interleukin 10 (IL10), (B) which were statistically significant, and (C) statistically significantly increased expression of TNFα compared with GFyoung. This change in phenotype corresponded to (D) increased levels of TNFα and (E) increased infiltration of CD45+ leukocytes in muscularis. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) After antibiotic (Abx) treatment, FMT was performed on old mice with young or old stool. Whole-gut transit times (WGTTs) were measured at baseline (pre-Abx), before FMT (post-Abx), and after FMT. (G) A statistically significant reduction in transit times was observed in mice after FMT with young stool (FTyoung) compared with before and after Abx treatment, which was not observed in mice transplanted with old stool (FTold). Data are combined from 2 independent experiments. n ≥ 5 for each group. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .005 by t test or 1-way analysis of variance, with the Bonferroni multiple comparisons test. Data are represented as means ± SD.

Next, we tested whether age-dependent differences in the microbiota influence gastrointestinal (GI) motility. Old mice were pretreated with an antibiotic cocktail and then fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) was performed by gavage of young or old mice stool. Whole-gut transit times were measured at baseline (pre-antibiotic treatment), before FMT (after antibiotic treatment), and after FMT (Figure 1F). FMT with young but not old stool resulted in a significant reduction in whole-gut transit times (Figure 1G). This suggests that in addition to altering MM phenotype, age-dependent factors in the microbiota affect gut motility.

Microbiota-mediated loss of barrier function is implicated in age-associated intestinal inflammation in Drosophila and mice,6, 8, 9 and appears to be TNFα-dependent.6 This suggests that microbial factors trigger an inflammatory response that presages disruption of barrier function. Bile acids (BAs) are a logical candidate because they are metabolized by the microbiota and known to modulate the immune response by signaling through host receptors.10 By using targeted metabolomics, we found increased deconjugated BAs in fecal pellets from old mice (Supplementary Figure 1A). Deconjugated primary BAs were increased in particular, showing a 20-fold increase compared with stool from young mice (Supplementary Figure 1B). Similarly, stool from GFold mice contained increased deconjugated primary BAs, suggesting that the MM phenotype in our colonized GF mice is mediated through BAs (Supplementary Figure 1C).

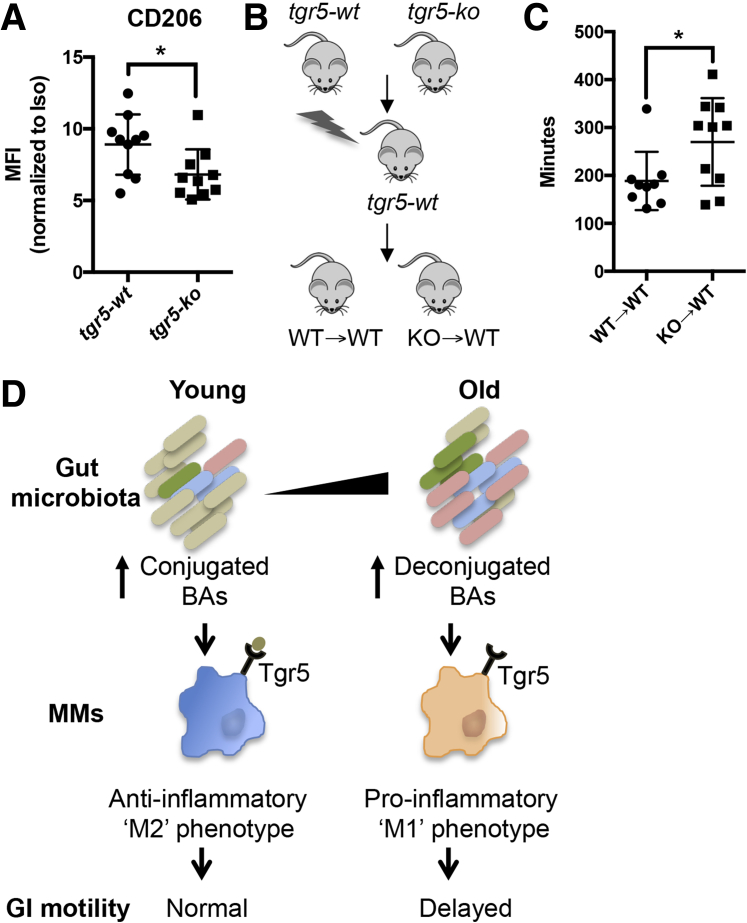

Takeda G-protein coupled receptor 5 (TGR5), also known as G-protein–coupled bile acid receptor 1, has been detected on human and mouse small intestinal macrophages3, 11 by RNA sequencing and can modulate the macrophage immune response.12 Tgr5 is differentially activated by various bile acids,12, 13 with conjugated BAs leading to greater affinity and activation than deconjugated equivalents.12, 14 We speculated that increased conjugated BAs in stool of young mice maintain an anti-inflammatory phenotype in MMs through TGR5 signaling. To test this, we performed immunophenotyping of MMs from TGR5 knockout mice (tgr5-ko) and wild-type littermates (tgr5-wt) by flow cytometry. MMs from tgr5-ko mice showed decreased surface expression of the M2 marker CD206 (Figure 2A), suggesting that TGR5 deficiency results in loss of M2 phenotype.

Figure 2.

TGR5 deficiency in MMs causes loss of M2 phenotype and delayed intestinal transit. (A) MMs from tgr5-ko mice showed statistically significantly decreased surface expression of M2 markers CD206 compared with tgr5-wt based on the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) normalized to isotype controls. (B) Bone marrow chimeras were generated by injecting bone marrow from tgr5-ko or tgr5-wt mice into lethally irradiated tgr5-wt mice. Data are combined from 2 independent experiments. (C) Mice transplanted with bone marrow from tgr5-ko mice (KO→WT) showed statistically significantly delayed intestinal transit compared with those transplanted with wild-type bone marrow (WT→WT). Data are representative of 2 independent whole-gut transit time experiments. (D) Proposed model by which age-dependent changes in microbiota cause a shift from conjugated to deconjugated BAs, resulting in a loss of M2 phenotype in MMs and delayed intestinal transit. n ≥ 9 for each group. *P < .05 by t test.

Tgr5-ko mice have been reported to show delayed intestinal transit.15 Because TGR5 is expressed in multiple cell types,15 we asked whether altered MM phenotype caused by TGR5 deficiency contributes to disrupted intestinal motility. We generated bone marrow chimeras by transplanting bone marrow from tgr5-ko or tgr5-wt mice into lethally irradiated tgr5-wt mice (Figure 2B). KO→WT chimeric mice showed delayed intestinal transit compared with WT→WT (Figure 2C), suggesting that decreased BA signaling through TGR5 in MMs contributes to age-related disruption in motility. Based on our results, we propose the following model for how aging affects GI motility (Figure 2D). Age-dependent alterations in gut microbiota cause a shift from conjugated to deconjugated BAs. This change in the conjugation status results in diminished TGR5 signaling on MMs, contributing to loss of anti-inflammatory phenotype and delayed intestinal transit. Our findings also offer several mechanistic and potential therapeutic interventions that might be used in treating age-related GI motility disorder. Further studies in human beings will be necessary to determine the clinical relevance.

Footnotes

Author contributions Laren Becker and Aida Habtezion were responsible for the study concept and design; Laren Becker, Estelle T. Spear, and Yeneneh Haileselassie acquired data; Laren Becker, Estelle T. Spear, and Sidhartha Sinha analyzed and interpreted data; Laren Becker drafted the manuscript; Laren Becker, Estelle T. Spear, Aida Habtezion, and Sidhartha Sinha critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; Laren Becker performed the statistical analysis; Laren Becker and Aida Habtezion obtained funding; and Laren Becker, Sidhartha Sinha, and Aida Habtezion provided resources and material support.

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK103966 (L.B.) and AG049622 (A.H.).

Contributor Information

Laren Becker, Email: lsbecker@stanford.edu.

Aida Habtezion, Email: aidah@stanford.edu.

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Animals

Male specific pathogen free C57BL/6 mice of different ages (2–3 mo and 18–24 mo) acquired from the NIA Aged Rodent Colony (Charles River Laboratories, Kingston, NY), GF and G-protein–coupled bile acid reported 1 constitutive knockout in a C57BL/6 background (tgr5-ko) acquired from Taconic (Rensselaer, NY), and B6.SJL (CD45.1) acquired from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), were used in experiments. Mice were housed in pathogen-free conditions and pathogen-free status was confirmed through constitutive monitoring of sentinel mice and specific testing of fecal samples for common mouse pathogens. All mice were housed in the same temperature- and humidity-controlled rooms with a 12-hour light:dark cycle and were maintained on ad libitum standard chow and water unless otherwise specified. For studies of the microbiota, to minimize cage effects, stool was sampled from either mice housed individually (old mice) or from individual animals from multiple cages. All animal experiments were approved by the Stanford University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Germ-Free Mice Microbiota Colonization

Six GF mice (age, 4 wk) were transferred to cages containing either 2-month-old or 24-month-old mice. The composition of each cage was 2 specific pathogen free mice and 3 GF mice. The mice were left undisturbed for 2 weeks and co-housed for a total of 4 weeks before fecal pellets were collected for analysis and tissue was harvested for flow cytometry (described later).

Tissue and Cell Preparation

Tissue was harvested as previously described.1 Briefly, small intestine was removed, lavaged, and the muscularis externa was dissected and either freshly frozen in dry ice or enzymatically digested with collagenase and papain. Tissue was dissociated mechanically by gentle trituration and filtered through a 100-μm nylon mesh cell strainer.

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed as previously described.1 Briefly, dissociated cells were incubated with Zombie Aqua Viability (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) followed by blocking with 5% rat serum and mouse anti-CD16/CD32 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) in Hank's balanced salt solution containing 2% bovine calf serum. Samples were incubated with the following anti-mouse primary antibodies or isotype control: Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated F4/80, Peridinin-Chrolrophyll-protein (PerCP)/Cy5.5-conjugated CD45, Pacific Blue–conjugated CD11c (Biolegend), PE/Cy7-conjugated CD3, PE/Cy7-conjugated CD19, Allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated CD206, PE-conjugated isotype control, and APC-conjugated isotype control (all from Biolegend). Sorting was performed directly into TRIzol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) using a BD FACS Aria (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). Analysis was performed using FlowJo Software (Tree Star, Inc, Ashland, OR).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA was extracted from cells with the miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) and converted to complementary DNA using the High-Capacity RNA-to-complementary DNA kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Complementary DNA preamplification was performed with TaqMan PreAmp Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed on an ABI StepOne Plus real-time instrument using the following TaqMan probes and primers: Hprt (Mm00446968; Applied Biosystems): found in inflammatory zone 1: forward, 5’-AGGAACTTCTTGCCAATCCA-3’; reverse, 5’-ACAAGCACACCCAGTAGCAG-3’; probe, 5’-CCTCCTGCCCTGCTGGGATG-3’; C-type lectin domain family 10 member A: forward, 5’-ACTGAGTTCCTGCCTCTGGT-3’; reverse,

5’-ATCTGGGACCAAGGAGAGTG-3’; probe, 5’-CACTGCTGCACAGGGAAG

CCA-3’; CD206: forward, 5’-TGATTACGAGCAGTGGAAGC-3’; reverse,

5’-GTTCACCGTAAGCCCAATTT-3’; probe, 5’-CACCTGGAGTGATGGTTC

TCCCG-3’; Arg1: forward, 5’-AGACCACAGTCTGGCAGTTG-3’; reverse,

5’-CCACCCAAATGACACATAGG-3’; probe, 5’-AAGCATCTCTGGCCACG

CCA-3’; interleukin 10: forward, 5’-CCCAGAAATCAAGGAGCATT-3’; reverse, 5’-TCACTCTTCACCTGCTCCAC-3’; probe, 5’-TCGATGACAGCGCCTCAGCC-3’; and

TNFα: forward, 5’-CCAAAGGGATGAGAAGTTCC-3’; reverse,

5’-CTCCACTTGGTGGTTTGCTA-3’; probe, 5’-TGGCCCAGACCCTCACACTCA-3’. For analysis, each gene was normalized to the housekeeping gene Hprt and fold change in gene expression between groups was calculated using the Pfaffl method.

Measurement of TNFα in Tissue Extract

Protein extract was obtained by lysing tissue in Ripa buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich), and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich). TNFα levels were assayed using mouse TNF-alpha enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with high sensitivity (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein concentrations were normalized to total protein using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Measurement of Gastrointestinal Transit Times

Carmine red (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared as a 6% (wt/vol) solution in filter-sterilized 0.5% methyl cellulose (Sigma-Aldrich). During a 3-day acclimation period, mice were housed individually, placed on a steel rack for 1–3 h/d, and sham gavaged. After an overnight fast, mice were gavaged with 0.3 mL of the carmine solution between 09:00 and 09:30 local time and monitored every 15–30 minutes for the appearance of the first red fecal pellet. The time from gavage to the passage of the first red pellet was recorded as whole-gut transit time.

Antibiotic Treatment

Old mice (age, 19–22 mo) were given drinking water containing 1 g/L ampicillin (Teknova, Hollister, CA), 1 g/L metronidazole (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 g/L streptomycin (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Santa Clara, CA), and 1 g/L vancomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 weeks.2

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation

Cecal contents were pooled from 2 donor mice of either 2 months (young) or 18 months (old) of age. According to a protocol adapted from Benakis et al,3 cecal content was resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (2.5 mL/cecum), filtered using a 100-μm nylon mesh cell strainer, and either immediately used or stored at −80°C until use. Mice previously treated with antibiotics were switched to nonmedicated water 4 days before fecal transplantation. FMT was performed by oral gavage of 200 μL of cecal extract on 2 occasions separated by 4 days.

Targeted Metabolomics Analysis

The Michigan Regional Comprehensive Metabolomics Resource Core performed targeted metabolomics analysis of stool for BAs. Briefly, 2-step solvent extraction was performed on samples. Supernatants were combined, dried, and resuspended for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry separation by reverse-phase liquid chromatography and measurements were performed by electrospray ionization triple quadrupole (ESI-QqQ) mass spectrometry with multiple reaction monitoring methods.

Generation of Bone Marrow Chimeras

Bone marrow chimeric mice were generated by lethally irradiating B6.SJL (CD45.1) mice (at 8–10 weeks) with 9.5-Gy γ radiation in 2 doses approximately 3 hours apart, followed by transfer of 5 × 106 bone marrow cells from tgr5-wt or tgr5-ko mice via retro-orbital injection. Chimeric mice were provided with antibiotics for the first 4 weeks and left to engraft for 10 weeks before gastrointestinal transit times were measured.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SD and were analyzed using the t test and 1-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni multiple comparisons test as detailed in Figures 1 and 2, and Supplementary Figure 1. n represents the number of animals and is specified in Figures 1 and 2, and Supplementary Figure 1. Significance was deemed when the P value was less than .05. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla CA).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Gordon S. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gautier E.L. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1118–1128. doi: 10.1038/ni.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabanyi I. Cell. 2016;164:378–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller P.A. Cell. 2014;158:300–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker L. Gut. 2018;67:827–836. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thevaranjan N. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21:455–466 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fransen F. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1385. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark R.I. Cell Rep. 2015;12:1656–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott K.A. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;65:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chavez-Talavera O. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1679–1694 e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bujko A. J Exp Med. 2018;215:441–458. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawamata Y. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9435–9440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haselow K. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:1253–1264. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0812396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poole D.P. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:814–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01487.x. e227–e228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alemi F. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:145–154. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Becker L. Gut. 2018;67:827–836. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller P.A. Cell. 2014;158:300–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benakis C. Nat Med. 2016;22:516–523. doi: 10.1038/nm.4068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.