Abstract

Background

Cervical spine infections are uncommon but potentially dangerous, having the highest rate of neurological compromise and resulting disability. However, the factors related to surgical success is multiple yet unclear.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 27 patients (16 men and 11 women) with cervical spine infection who underwent surgical treatment at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou branch, between 2001 and 2014. The neurological status, by Frankel classification, was recorded preoperatively and at discharge. Group X had neurologic improvement of at least 1 grade, group Y had unchanged neurologic status, and group Z showed deterioration. We recorded the patient demographic data, presenting symptoms and signs, interval from admission to surgery, surgical procedure, laboratory data, perioperative antibiotic course, pathogens identified, coexisting medical disease, concomitant nonspinal infection, and clinical outcomes. We intended to evaluate the different characteristics of patients who improved neurologically after treatment.

Results

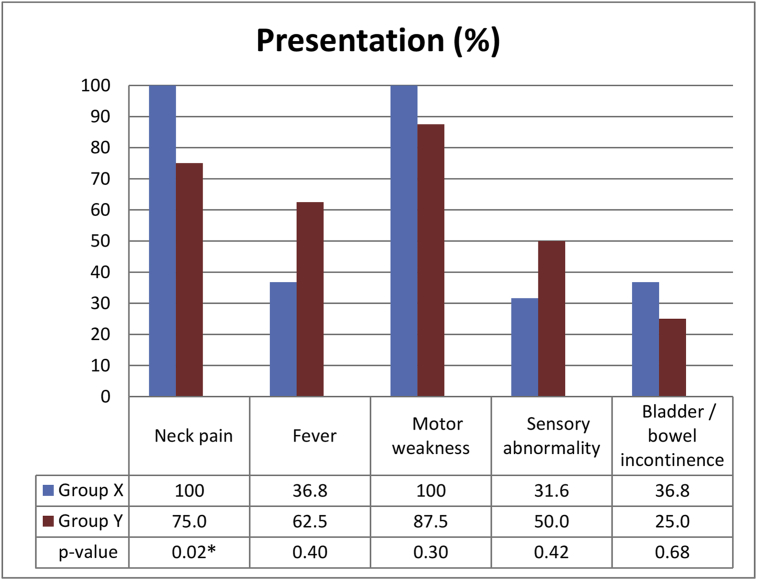

The mean age of our cohort was 56.6 years. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion was the most commonly performed surgical procedure (74.1%). The Frankel neurological status improved in 70.4% (group X, n = 19) and unchanged in 29.6% (group Y, n = 8). No patients worsened. Motor weakness was most common (96.3%) neurological deficit, followed by sensory abnormalities (37.0%), and bowel/urine incontinence (33.3%). The main difference in presentation between group X and group Y was neck pain (100% vs. 75.0%; p = .02), not fever. Group X had a shorter preoperative antibiotic course (p = .004), interval from admission to operation (p = .02), and hospital stay (p = .01).

Conclusion

Clinicians should be more suspicious in patients who present with neck pain and any neurological involvement even in those without fever while establishing early diagnosis. Earlier operative treatment in group X result in better neurologic recovery and shorter hospital stay due to disease improvement.

Keywords: Spondylodiscitis, Epidural abscess, Osteomyelitis, Neurologic manifestation, Risk factors

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

Neurological involvement is the result of early infection cervical cord invasion. Earlier operative treatment together with antibiotic therapy would effectively reduce the infection burden, since cervical spine infection is more dangerous as it results in the highest rate of neurologic compromise.

What this study adds to the field

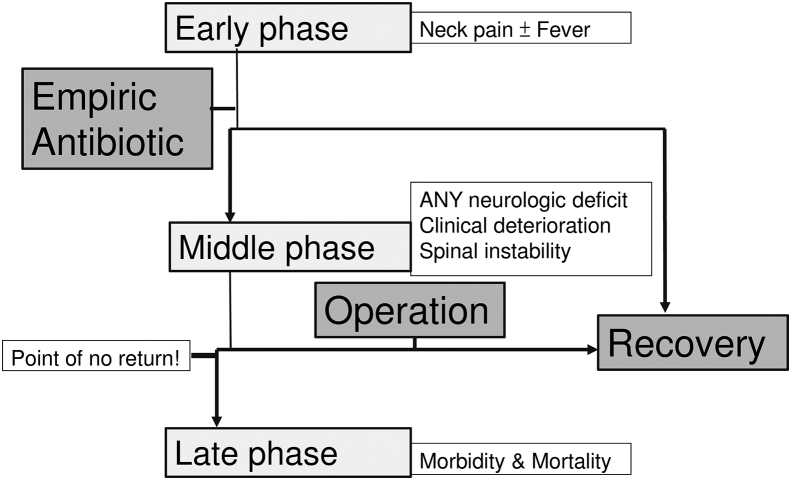

This study adds to the field a proposed algorithm for phases of cervical spine infection. Deterioration could progress faster than any other segment of spine infection. When the disease goes beyond the point of no return, even aggressive surgical treatment eradicating the infection would hardly reverse the neurological deficit.

Pyogenic spinal infection (PSI) is an uncommon disease affecting 1%–7% of all patients with pyogenic osteomyelitis [1]. The cervical spine is less frequently involved than other spinal segments, but cervical spine infection is more dangerous as it results in the highest rate of neurologic compromise [2], [3], [4]. Establishing an early diagnosis and treating in a timely fashion is the gold standard for dealing with cervical PSI [4], [5], [6], [7], [8].

Surgical treatment of cervical PSI includes radical debridement and reconstruction of the defect, with or without instrumentation [9]. The outcome of surgery often depends on patient risk factors (such as aging, immunosuppressive conditions, and complex comorbidities), the presence of neurologic-function decline, and time to surgery after medical-therapy failure. Little is known on how these factors affect neurologic improvement.

The purpose of our study was to retrospectively review all patients who underwent surgical management of cervical PSI over the past 14 years at our institution and to analyze the risk factors for these infections and their clinical course, based on the surgical outcome. We also evaluated the different characteristics of patients who improved neurologically after treatment.

Material and methods

After institutional review board approval, we retrospectively reviewed the electronic medical records of patients who underwent surgical management of PSI at our institution between January, 2001 and December, 2014. A total of 1043 consecutive patients were evaluated; 27 had infection located in the cervical spine (2.6%); these patients were selected for study inclusion. The study patients had different types of cervical PSI: spondylodiscitis, vertebral osteomyelitis, epidural abscess, and paravertebral abscess.

Diagnosis required compatible clinical, hematological, and radiographic examinations; the latter mainly consisted of gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We collected the following patient data: age; sex; spinal level of infection; presentation; extent of neurological impairment both at presentation and at discharge; length of hospital stay, antibiotic-treatment choice and duration, comorbidities including diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic or end-stage renal disease, cardiac disease including coronary artery disease and hypertensive cardiovascular disease, hepatic disease including hepatitis B or C viral infection and liver cirrhosis, nicotine abuse, malignancy, and other nonspinal infection foci including urinary tract infection (UTI), infective endocarditis (IE), and pneumonia. Laboratory data consisted of the white blood-cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and the bacterial pathogens isolated from blood- or surgical cultures.

Patients were admitted to either the surgery- or internal medicine department; consultation between services occurred on a case-by-case basis. The initial treatment decisions were made by the primary treatment team and were guided by the patients' presenting neurologic status and medical comorbidities. All patients in this series underwent combined antibiotic therapy and surgical intervention. The indications for surgery included progressive neurological deficits, intractable neck pain, the presence of an epidural abscess, septicemia, spinal instability, and persistent infection with failed medical treatment. The surgical procedures involved radical surgical debridement with decompression of the spinal canal and reconstruction of the defect; we obtained tissue cultures for bacterial, fungal, tuberculosis, and histological examination. The graft used for interbody fusion was either obtained from the patient's iliac crest or was an allograft from our bone bank. Initial broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy was adjusted according to the isolated organism's sensitivity and typically continued for 6–12 weeks, depending on disease severity and clinical progression. A semirigid cervical collar was applied for at least 3 months, until radiographic fusion was confirmed during follow-up. Symptoms, neurologic status, laboratory parameters, and the results of plain radiography were recorded at each follow-up visit; the length of follow-up was defined as the time from diagnosis (MRI completion) to the final clinic visit. The Frankel classification was used to assess neurological status and was recorded at the time of diagnosis and at discharge.

Patients were categorized into 3 groups, based on the difference in Frankel grade between admission and discharge:

-

●

Group X: neurologic improvement of at least 1 Frankel grade

-

●

Group Y: neurologic grade unchanged

-

●

Group Z: neurologic deterioration of at least 1 Frankel grade

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Comparisons were done using the student t test and Mann–Whitney U test when indicated for continuous variables and the chi-square test and Fisher's exact test when indicated for categorical variables. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Theory

We hypothesized that those who had not improved neurologically after treatment will have some risk factors such as old age [10], fever, neck pain, more impaired neurologic presentation [10], poorer laboratory data [11], more comorbidities [6], [8], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], resistant organism [10], and other non-spinal infections [15] necessitating longer antibiotic treatment, hospital stay and complications [10].

Results

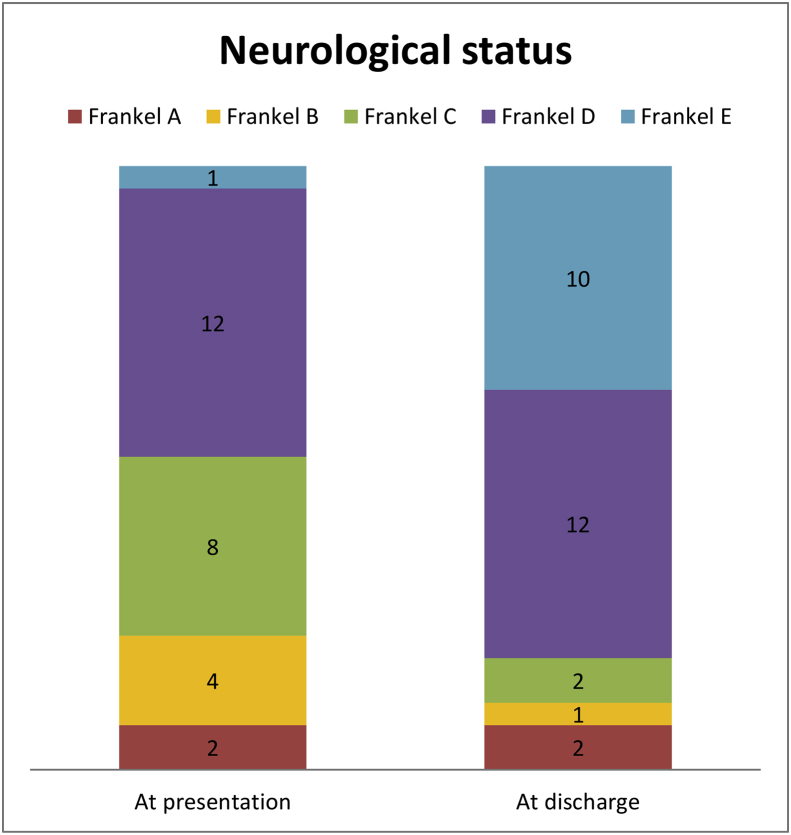

There were 16 male and 11 female patients; the demographic data are listed in Table 1. Table 2 gives the diagnosis and lists the presence of concomitant medical conditions and other nonspinal infections, while Fig. 1 depicts patients’ neurologic status at presentation and at discharge.

-

●

Group X: 19 patients had neurologic improvement from preoperative Frankel grade A (n = 0), B (n = 3), C (n = 8), D (n = 8), and E (n = 0); 17 of these had improvement of 1 Frankel grade (8 from grade D, 7 from grade C, and 2 from grade B), and 2 patients had improvement of 2 Frankel grades (1 from grade B and 1 from grade C).

-

●

Group Y: Eight patients had unchanged neurological status from preoperative Frankel grade A (n = 2), B (n = 1), C (n = 0), D (n = 4), and E (n = 1) Group Z: No patients had neurologic deterioration.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Variables | All patients (n = 27) | Group X (n = 19) | Group Y (n = 8) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56.6 ± 14.11 | 55.8 ± 14.71 | 58.5 ± 13.30 | .55 |

| Levels (no. of discs crossed by abscess) | 2.4 ± 2.11 | 2.5 ± 2.41 | 2.1 ± 1.25 | .70 |

| Preoperative antibiotic days | 15.0 ± 19.78 | 9.7 ± 17.57 | 28.6 ± 19.79 | .004* |

| Postoperative antibiotic days | 31.5 ± 15.83 | 29.3 ± 12.14 | 37.3 ± 23.04 | .53 |

| Interval from admission to OR (days) | 12.9 ± 14.65 | 10.2 ± 14.55 | 19.4 ± 13.59 | .02* |

| Hospital stay (days) | 51.0 ± 25.96 | 43.7 ± 21.53 | 66.1 ± 27.25 | .01* |

| Follow-up (months) | 29.98 ± 42.03 | 29.8 ± 38.50 | 30.39 ± 52.44 | .97 |

| WBC (/μL) | 11,959.3 ± 6669.00 | 12,773.7 ± 7495.49 | 10,025.0 ± 3827.63 | .42 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 111.0 ± 102.13 | 123.9 ± 95.51 | 81.7 ± 117.00 | .31 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 77.94 ± 29.03 | 83.4 ± 31.01 | 67.00 ± 23.14 | .25 |

There was statistically significant difference between group X and group Y in preoperative antibiotic days and hospital stay. *: significant values.

Group X: neurologic improvement of at least 1 Frankel grade; Group Y: neurologic grade unchanged; Abbreviations: OR: operation room; WBC: white blood-cell; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Table 2.

Coexisting medical diseases and other nonspinal infections, n (%).

| Diagnosis | All patients (n = 27) | Group X (n = 19) | Group Y (n = 8) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spondylodiscitis | 24 (88.9%) | 16 (84.2%) | 8 (100%) | .53 |

| Epidural abscess | 19 (70.4%) | 15 (78.9%) | 4 (50.0%) | .18 |

| Paravertebral abscess | 5 (18.5%) | 4 (21.1%) | 1 (12.5%) | >.99 |

| Postoperative infection | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 | >.99 |

| Coexisting medical disease | ||||

| Nicotine abuse | 12 (44.4%) | 9 (47.4%) | 3 (37.5%) | .70 |

| Diabetes | 9 (33.3%) | 6 (31.6%) | 3 (37.5%) | >.99 |

| Cardiac | 9 (33.3%) | 5 (26.3%) | 4 (50.0%) | .38 |

| Hepatic | 8 (29.6%) | 5 (26.3%) | 3 (37.5%) | .66 |

| Renal | 5 (18.5%) | 3 (15.8%) | 2 (25.0%) | .61 |

| Malignancy | 3 (11.1%) | 2 (10.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | >.99 |

| Old stroke | 2 (7.4%) | 2 (10.5%) | 0 | >.99 |

| Neck radiation | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 | >.99 |

| Intravenous drug use | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 | >.99 |

| Other nonspinal infection | ||||

| Urinary tract infection | 10 (37.0%) | 6 (31.6%) | 4 (50.0%) | .42 |

| Infective endocarditis | 3 (11.1%) | 1 (5.3%) | 2 (25.0%) | .20 |

| Pneumonia | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 | >.99 |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 | >.99 |

| Deep neck infection | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 | >.99 |

| Any other nonspinal infection | 16 (59.3%) | 10 (52.6%) | 6 (75.0%) | .40 |

Cervical spondylodiscitis was the most frequent diagnosis. Risk factors such as coexisting medical disease and other nonspinal infection failed to distinguish group X from group Y.

Fig. 1.

Neurological status at presentation and at discharge. 19 patients had neurologic improvement (group X), and the other 8 patients had unchanged neurological status (group Y). No patient had neurologic deterioration.

Demographic data and preoperative course

The mean age of our cohort was 56.6 years (range, 25–82 years) at the time of surgery. The number of discs crossed by abscess was 2.4 (standard deviation, 2.11). The mean duration of preoperative and postoperative antibiotic therapy was 15.0 and 31.5 days, respectively. The mean interval from admission to surgery was 12.9 days (range, 0–55 days). The WBC, CRP, and ESR levels were elevated in most patients, averaging 11,959.3/μL, 111.0 mg/L, and 77.94 mm/h, respectively. Between group X and group Y, there were significant shorter mean preoperative antibiotic course (9.7 vs. 28.6 days, p = .004) and shorter interval from admission to operation (10.2 vs. 19.4 days, p = .02). No other differences were identified in age, level, or laboratory data.

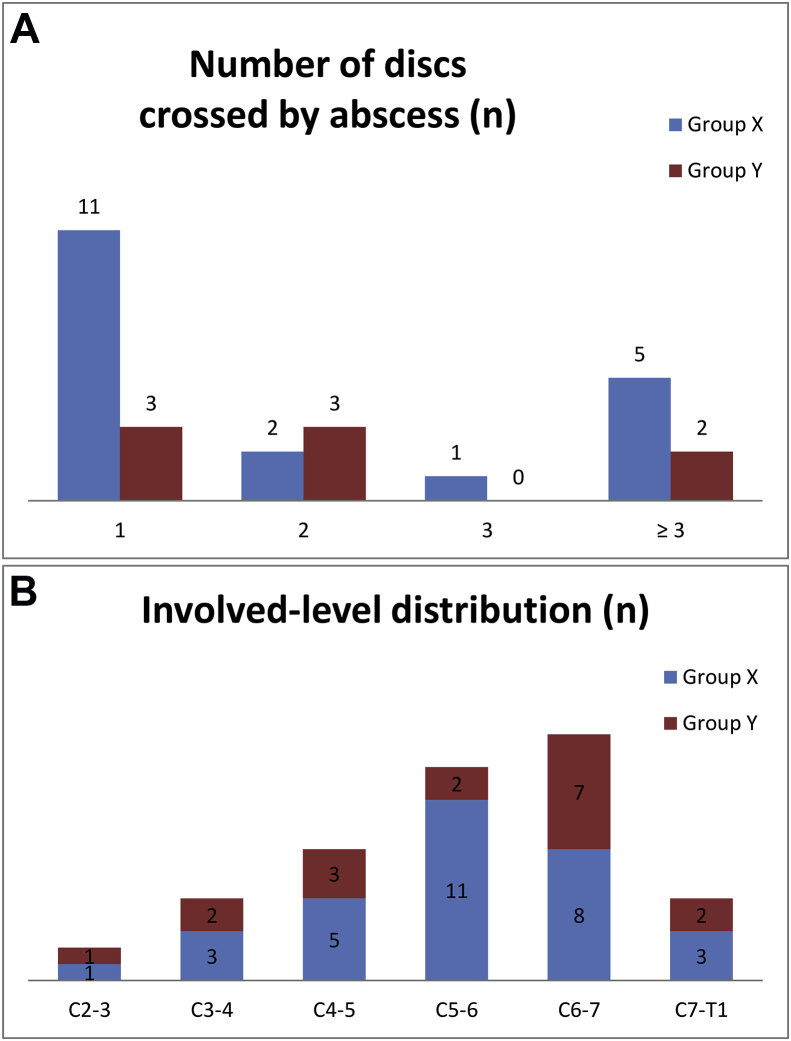

Cervical spondylodiscitis was the most frequent diagnosis (present in 88.9% of patients) and involved a single spinal level in 14 patients (51.9%), 2 levels in 5 patients (18.5%), and 3 levels in 1 patient (3.7%) (Fig. 2A). The remaining 7 patients presented with an epidural abscess that affected more than 3 cervical spinal levels. The most frequently involved level was C6-7 (30.6%), followed by C5-6 (26.5%), and C4-5 (18.4%) (Fig. 2B). Epidural abscess was present in 19 of the 27 patients (70.4%), either alone (11.1%) or with spondylodiscitis (59.3%). Nicotine abuse was the most prevalent coexisting medical condition (present in 44.4% of patients), followed by DM (33.3%). Only 3.7% of patients were intravenous drug users. A presumed source of infection was found in 16 patients (59.3%): UTI was the most common (37.0%), followed by IE (11.1%). One patient had a history of anterior cervical instrumentation, performed 3 years prior for degeneration. There was no statistical difference between group X and group Y in diagnosis, coexisting medical disease, or other nonspinal infections (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Level of involvement in cervical spine infection (A) and involved-level distribution (B). Cervical spine infection involved a single spinal level in 14 patients (51.9%), 2 levels in 5 (18.5%), and the most frequently involved level was C6-7 (30.7%), and C5-6 (26.5%). There was no significant difference between group X and group Y.

Neck pain was present in 25 patients (92.6%): 100% of group X and 75.0% of group Y (p < 0.05). Fever was present in 12 patients (44.4%), with no statistical difference between group X and group Y (36.8% and 62.5%, respectively). All 27 patients had varying degrees of neurologic impairment, with motor weakness the most common, seen in 26 patients (96.3%), followed by sensory abnormalities in 10 (37.0%) and bowel/urine incontinence in 9 (33.3%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Presentation of patients with pyogenic cervical spine infection. Neck pain was present in 100% of group X and 75.0% of group Y, with statistically significant difference (*) between group X and Y. Fever appears less than half of the patients and had no statistical difference between group X and group Y. All 27 patients had varying degrees of neurologic impairment.

The most common neurologic grade at presentation was Frankel grade D in 12 patients (44.4%), followed by Frankel grade C in 8 patients (29.3%). There was no statistical difference in the presenting neurologic deficit between group X and group Y. A total of 17 patients (63.0%) were referred from internal medicine for surgical intervention. The ratio of referral was lower in group X than in group Y (52.6% vs. 87.5%), but this difference was statistically insignificant (p = .19).

Operative findings

All 27 patients underwent radical surgical debridement and reconstruction of the resulting defect when necessary. Table 3 shows the different surgical modalities applied. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) was the most commonly performed technique (in 74.1% of patients), followed by anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (14.8%). The choice of whether to perform corpectomy was based on the preoperative imaging findings, the spinal levels crossed by the abscess, and the clinical experience of the surgeon.

Table 3.

Surgical procedure, n (%).

| Operative procedure | All patients (n = 27) | Group X (n = 19) | Group Y (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion | 20 (74.1%) | 14 (73.7%) | 6 (75.0%) |

| Anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion | 4 (14.8%) | 2 (10.5%) | 2 (25.0%) |

| Posterior laminectomy or laminotomy | 4 (14.8%) | 4 (21.1%) | 0 |

| Anterior plus posterior surgery | 2 (7.4%) | 2 (10.5%) | 0 |

| Fusion choice | |||

| Iliac crest autograft | 22 (81.5%) | 15 (78.9%) | 7 (87.5%) |

| Allograft | 2 (7.4%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Anterior plate | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 |

| Posterior instrumentation | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 |

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion was the most commonly performed technique. Posterior approach was either performed for isolated epidural abscess or together with anterior approach for increasing stability. Fusion with an autogenous iliac graft, rather than a cage, was used in 22 patients (81.5%) for interbody fusion.

An autogenous iliac graft, rather than a cage, was used in 22 patients (81.5%) for interbody fusion. One patient underwent anterior plating (3.7%) and 1 underwent posterior instrumentation (3.7%). The anterior approach was predominant; posterior-approach laminectomy or laminotomy were performed in the 4 patients (14.8%) including 2 patients undergoing anterior and posterior surgery at a same time for removal of epidural abscess and increase vertebral stability.

An important step in each surgery was to obtain material for bacteriological examination. The causative pathogen was successfully identified in 17 patients (63.0%), while 10 patients (37.0%) were culture-negative (Table 4). The most commonly isolated organism was Staphylococcus aureus in 9 patients (33.3%); 6 of these samples were resistant to methicillin (MRSA).

Table 4.

Pathogen status, n (%).

| Pathogen | |

|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 9 (33.3%) |

| Escherichia sp | 2 (7.4%) |

| Streptococcus sp | 1 (3.7%) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1 (3.7%) |

| Corynebacterium sp | 1 (3.7%) |

| More than 1 agenta | 3 (11.1%) |

| Not identified | 10 (37%) |

The pathogen was identified in 17 patients (63.0%), while 10 patients (37.0%) were culture-negative. The most common was Staphylococcus aureus in 9 patients (33.3%); 6 of these samples were methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Three patients had polymicrobial findings: 1 with Enterococcus avium, Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, and Peptostreptococcus sp; 1 with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Proteus vulgaris; 1 with Streptococcus oralis and Haemophilus parainfluenzae.

Postoperative course and complications

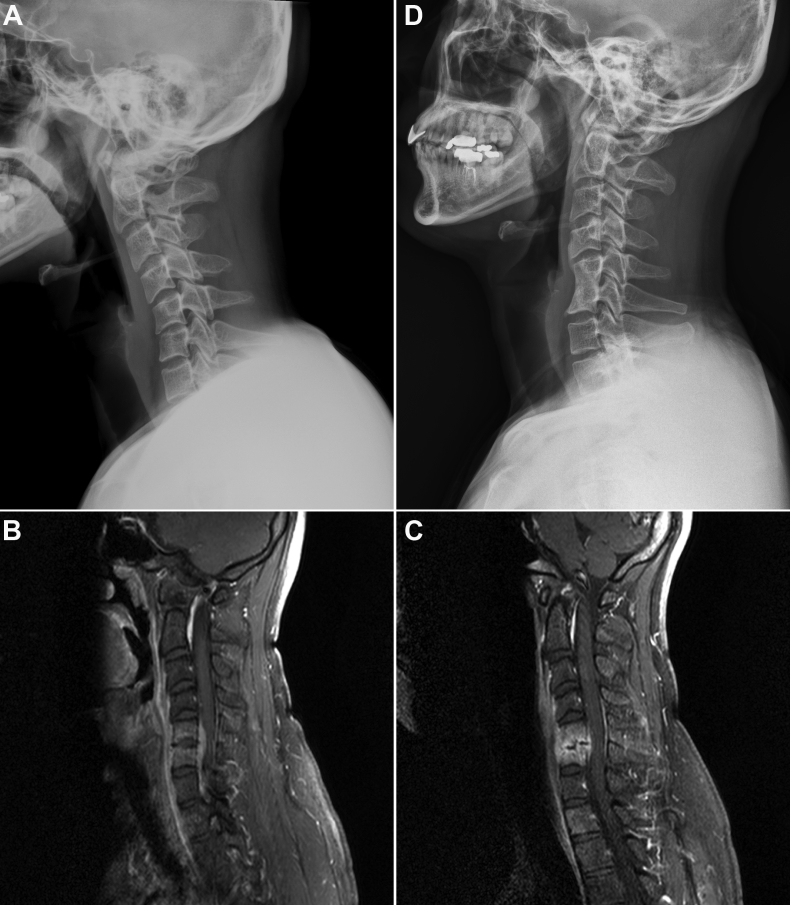

Infection subsidence and inflammatory healing was achieved clinically, hematologically, and radiologically in 26 patients (96.3%) at final follow-up. The mean duration of follow-up was 29.98 months (range, 0.8–157.6 months), without group difference (Table 1). The mean duration of hospital stay was significantly shorter in group X (43.7 vs. 66.1 days, p = .01). Fig. 4 shows a typical patient with infective spondylodiscitis at C5-6 (Fig. 4A, B) who had clinical deterioration and new neurologic deficit at 4 weeks of antibiotic treatment, when repeat MRI showed C5-6 endplate destruction and stationary epidural abscess causing thecal sac compression (Fig. 4C). He had improved neurological status, from Frankel grade D to grade E, after ACDF and successful fusion (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Case presentation. This is a typical patient with infective spondylitis at C5-6 (A) Plain lateral cervical radiography and (B) Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging at diagnosis. (C) Surgical intervention, anterior cervical discectomy with autograft, was at 4 weeks of antibiotic treatment, when clinical deterioration and new neurologic deficit dawned. MRI then showed C5-6 endplate destruction and stationary epidural abscess causing thecal sac compression. After surgery, he improved from Frankel grade D to grade E. (D) Radiography of the same patient 20 months after operation showing successful fusion.

One patient died (3.7%) in the third postoperative week, due to advanced septicemia and multisystem organ failure. This female patient had been referred from a local hospital with a 6-month history of chronic intractable infection and medical-treatment failure. Infection recurred in 2 patients (7.4%): one subsequently underwent ultrasound-guided abscess drainage at the posterior paraspinal region in the fourth postoperative week; the other had residual infection and bone graft fracture, necessitating revision surgery in the second postoperative month.

A persistent neurological deficit occurred in 6 patients (22.2%) who had a poor preoperative Frankel status (2 with grade A, 3 with grade B, and 1 with grade C). One of the patients with Frankel grade A developed an intractable sacral bedsore requiring multiple debridements and ultimately a transverse-loop colostomy; the other patient with Frankel grade A developed a donor-site infection at the iliac crest necessitating debridement. One of the patients with preoperative Frankel grade C developed donor-site infection and later ascending colon colitis in the same hospital stay. He had iliac donor site debridement and then ascending colon colectomy and end-ileostomy. Despite these complications, no patients experienced postoperative neurological deterioration.

Discussion

Cervical PSI is an uncommon but potentially dangerous condition, with the highest rate of neurologic compromise of all PSIs [2], [3], [4]. The absolute incidence is low, and the condition is poorly studied, but a recent article by Shousha et al. [9] reviews the relative incidence of cervical PSI compared with other-segment PSI; they report that cervical involvement accounts for 4%–19% of all PSIs. In our series, the relative incidence is 2.6%. This low rate of cervical spine involvement may be due to our country's access to medical care in the early-infection phase. However, the condition warrants closer surveillance and perhaps a more aggressive therapeutic approach.

Clinicians should be alert to the possibility of cervical disease when patients present with neck pain and neurological deficits; uncharacteristic symptoms may delay the use of conventional radiography [2], [16], [17], [18], and thereby delay the final diagnosis by 12–15 weeks [5], [6]. The neck pain related to cervical spine infection is basically a posterior nuchal, gradual onset, aggravating and intractable pain, sometimes associated with resting and night pain, and cannot be relieved by specific neck movement [19]. The neck pain is often reported to be the leading symptom of cervical spine infection. [3], [20], while sometimes neurological impairment leads [14]. In our series, the frequency of neck pain was as high as 92.6%, and this symptom was a statistically significant factor in predicting postoperative neurologic improvement. The interval to diagnosis appears to be among the most important prognostic factors [6], and the presence of neck pain with a neurologic deficit helps in establishing an early diagnosis, aiding the timely treatment of cervical PSI. In comparison, fever was observed to be less stronger, and cannot be relied on as a negative predictive sign. Being a normally important sign, fever was present in merely 38–50% in the relevant literature [5], [7], [12], [13], [18], [21], and in 44.4% of our patients.

Early and aggressive surgery is applied in almost all publications that discuss cervical PSI [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [12], [13], [14], [15], [21], [22]. We achieved a 96.3% local-infection control rate and a 70.4% neurological-improvement rate. No neurological deterioration occurred after surgical management. Shousha et al. [15] treated 50 patients with spondylodiscitis, all of whom were free of infection; 58%–67% of patients had neurologic improvement. Ghobrial et al. [22] evaluated 31 patients with cervical epidural abscess and a preoperative neurologic deficit: 51% had neurologic improvement, and 1 patient deteriorated by 1 grade. Our perioperative complication rate was low, and our mortality was 3.7%, consistent with the reported data of 5%–21% mortality [4], [15].

It is worth mentioning that early surgery, in the presence of any neurologic defect (instead of limiting surgery to progressive deficits), will achieve better neurologic recovery. Since neurologic function declines dramatically and precipitously in patients with cervical PSI [15], [23], a delay in diagnosis and a subsequent delay in surgical intervention will result in complications and even mortality [4], [6], [20], [23]. Karadimas [24] found still around 30% of patient who were neurologically normal needed operation, a highest rate as compared to PSI in other segments. Alton et al. [8] conclude that, compared with medical failure and delayed surgery, early surgery in patients with cervical epidural abscess results in improved post-treatment motor scores. In our series, the group with neurologic improvement (group X) had a statistically shorter duration of preoperative antibiotic therapy and a shorter hospital stay. It implies that delayed surgery after antibiotic-treatment failure is associated with a lower potential for neurological improvement. Delaying surgical intervention in favor of antibiotic treatment also has a detrimental effect on the potential for neurological improvement. We thus developed a treatment algorithm (Fig. 5) based on the findings above. We highly recommend surgical intervention in the early phase of infection, or whenever neurologic deficits are present, to avoid disastrous disease progression.

Fig. 5.

Proposed algorithm for cervical spine infection treatment. There should be a high degree of suspicion in evaluating for deterioration of their condition in every cervical spine infection, for it always comes dramatically. Successful surgical intervention should be done in the early phase of infection, whenever neurologic deficits are present, or at least before the point of no return.

Our study has several limitations. First, there was no comparison group with conservative management alone. However, when to use medical treatment alone is still unclear. Studies showed the best candidates were those with immune-competency, neurologically normal at baseline, and have a susceptible infective low-virulence organism [8]. Thus there are inherent difficulty to any attempt to compare these two mismatched groups due to selection bias such as inconsistent indication, and pre-existing clinical diseases. Second, the number of patients was relatively small to show a statistical significance in some factors such as the referral ratio and interval from admission to surgery. Third, in retrospective study design, measure of neurologic status such as ASIA class or score cannot be provided to more accurately reflect neurologic improvement. To overcome these limitations and to cover the whole spectrum of cervical PSI, a multicenter prospective study enrolling consecutive patients is crucial.

Conclusions

Cervical PSI is notorious for its high mortality and morbidity. Diagnostic suspicion should be raised when patients present with neck pain and neurologic deficits; in contrast, fever cannot be relied on as a diagnostic sign. Early diagnosis and aggressive surgery in the presence of any neurologic deficit (as opposed to limiting surgery to patients with progressive deficits) will improve recovery. Early surgery together with antibiotic therapy leads to clinical improvement and healing of inflammation, halting neurologic deterioration and leading to shorter hospital stay.

Conflicts of interest

The authors certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest, or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.D'Agostino C., Scorzolini L., Massetti A.P., Carnevalini M., d'Ettorre G., Venditti M. A seven-year prospective study on spondylodiscitis: epidemiological and microbiological features. Infection. 2010;38:102–107. doi: 10.1007/s15010-009-9340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Endress C., Guyot D.R., Fata J., Salciccioli G. Cervical osteomyelitis due to i.v. heroin use: radiologic findings in 14 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155:333–335. doi: 10.2214/ajr.155.2.2115262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muzii V.F., Mariottini A., Zalaffi A., Carangelo B.R., Palma L. Cervical spine epidural abscess: experience with microsurgical treatment in eight cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;5:392–397. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.5.5.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urrutia J., Zamora T., Campos M. Cervical pyogenic spinal infections: are they more severe diseases than infections in other vertebral locations? Eur Spine J. 2013;22:2815–2820. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2995-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krodel A., Sturz H., Siebert C.H. Indications for and results of operative treatment of spondylitis and spondylodiscitis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1991;110:78–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00393878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heyde C.E., Boehm H., El Saghir H., Tschoke S.K., Kayser R. Surgical treatment of spondylodiscitis in the cervical spine: a minimum 2-year follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1380–1387. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0191-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schinkel C., Gottwald M., Andress H.J. Surgical treatment of spondylodiscitis. Surg Infect. 2003;4:387–391. doi: 10.1089/109629603322761445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alton T.B., Patel A.R., Bransford R.J., Bellabarba C., Lee M.J., Chapman J.R. Is there a difference in neurologic outcome in medical versus early operative management of cervical epidural abscesses? Spine J. 2015;15:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shousha M., Boehm H. Surgical treatment of cervical spondylodiscitis: a review of 30 consecutive patients. Spine. 2012;37:E30–E36. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31821bfdb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S.D., Melikian R., Ju K.L., Zurakowski D., Wood K.B., Bono C.M. Independent predictors of failure of nonoperative management of spinal epidural abscesses. Spine J. 2014;14:1673–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel A.R., Alton T.B., Bransford R.J., Lee M.J., Bellabarba C.B., Chapman J.R. Spinal epidural abscesses: risk factors, medical versus surgical management, a retrospective review of 128 cases. Spine J. 2014;14:326–330. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arko Lt, Quach E., Nguyen V., Chang D., Sukul V., Kim B.S. Medical and surgical management of spinal epidural abscess: a systematic review. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;37:E4. doi: 10.3171/2014.6.FOCUS14127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn B.S., Kim K.H., Kuh S.U., Park J.Y., Chin D.K., Kim K.S. Surgical treatment in patients with cervical osteomyelitis: single institute's experiences. Kor J Spine. 2014;11:162–168. doi: 10.14245/kjs.2014.11.3.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozkan N., Wrede K., Ardeshiri A., Hagel V., Dammann P., Ringelstein A. Cervical spondylodiscitis--a clinical analysis of surgically treated patients and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;117:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shousha M., Heyde C., Boehm H. Cervical spondylodiscitis: change in clinical picture and operative management during the last two decades. A series of 50 patients and review of literature. Eur Spine J. 2015;24:571–576. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heindel W., Lanfermann H., du Mesnil R., Fischbach R. Infections of the cervical spine. Aktuelle Radiol. 1996;6:308–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruiz A., Post J.D., Ganz W.I. Inflammatory and infectious processes of the cervical spine. Neuroimaging Clin. 1995;5:401–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klockner C., Valencia R., Weber U. Alignment of the sagittal profile after surgical therapy of nonspecific destructive spondylodiscitis: ventral or ventrodorsal method: a comparison of outcomes. Der Orthopäde. 2001;30:965–976. doi: 10.1007/s001320170010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaundy W., Lee J., Berger J. Cervical spondylodiscitis as a rare presentation of neck pain in a systemically well patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-206239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walter J., Kuhn S.A., Reichart R., Kalff R., Ewald C. PEEK cages as a potential alternative in the treatment of cervical spondylodiscitis: a preliminary report on a patient series. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1004–1009. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1265-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mann S., Schutze M., Sola S., Piek J. Nonspecific pyogenic spondylodiscitis: clinical manifestations, surgical treatment, and outcome in 24 patients. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;17:E3. doi: 10.3171/foc.2004.17.6.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghobrial G.M., Viereck M.J., Margiotta P.J., Beygi S., Maulucci C.M., Heller J.E. Surgical management in 40 consecutive patients with cervical spinal epidural abscesses: shifting toward circumferential treatment. Spine. 2015;40:E949–E953. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schimmer R.C., Jeanneret C., Nunley P.D., Jeanneret B. Osteomyelitis of the cervical spine: a potentially dramatic disease. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15:110–117. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200204000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karadimas E.J., Bunger C., Lindblad B.E., Hansen E.S., Hoy K., Helmig P. Spondylodiscitis. A retrospective study of 163 patients. Acta Orthop. 2008;79:650–659. doi: 10.1080/17453670810016678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]