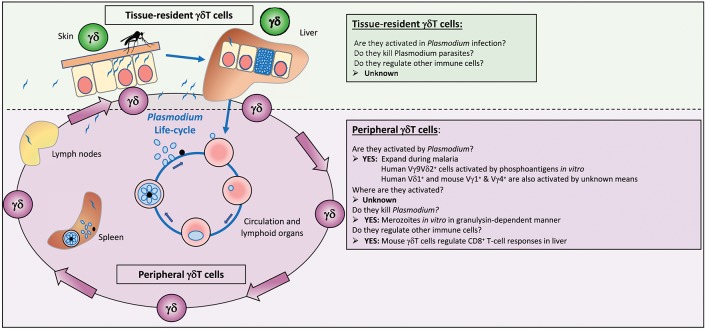

Figure 1.

γδT cells in malaria. Infected mosquitoes inject Plasmodium parasites in the form of sporozoites into the skin of a susceptible host from where they migrate to the liver to find an appropriate hepatocyte for invasion and replication. Some of these sporozoites will end up in lymphoid organs, such as spleen and lymph nodes as well. The parasite in hepatocytes undergoes rapid multiplication to form merozoites, which burst out of the infected cell and enter the blood circulation where they infect red blood cells and initiate multiple rounds of maturation and replication until the immune system manages to eliminate the parasites from the blood. During all these different steps—passage from skin to liver to blood—γδT cells present in the tissues (both tissue-resident and circulating γδT cells) could recognize parasites and become activated. Circulating γδT cells become activated during malaria, but nothing is known about where they are activated, whether in the skin, the liver or the lymphoid organs, and whether they really contribute to the antiparasite response during a natural infection. Tissue-resident γδT cells in the skin and liver could become activated, and protect against a new infection. Even less is known about responses of tissue-resident γδT cell subsets, the antigens they recognize, and whether they are able to kill sporozoites or infected hepatocytes.