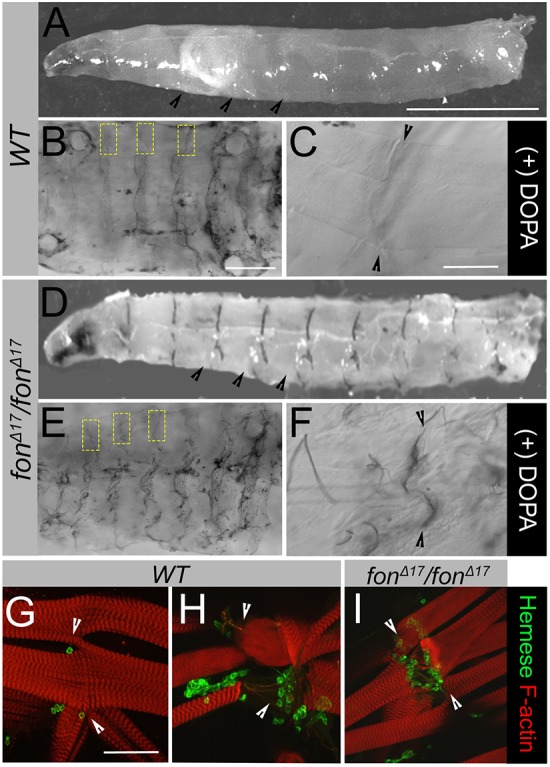

Fig. 3.

Loss of Fon activates innate immune processes. (A–F) Presence of melanin in wild-type (WT) versus fonΔ17 homozygous mutants visualized in exterior views (A,D) and dissected muscle fillets (B,C,E,F). (A) Wild-type larvae lack a visible melanization response throughout the body cavity or MASs (black arrowheads). (B) Addition of the phenoloxidase substrate, L-DOPA, allows for conversion into melanin which collects non-specifically throughout the cuticle of wild-type larvae. Areas containing MASs along the hemisegmental borders are marked with yellow dashed boxes. (C) Wild-type muscle attachments (black arrowheads) imaged at higher magnification are free of melanin. (D) Melanin is spontaneously deposited at MASs (black arrowheads) in low percentages (∼5%) of fonΔ17 mutant larvae. (E) Melanization at MASs (yellow boxes) can be induced by providing excess L-DOPA substrate to dissected fillets. (F) High magnification of melanin deposits at muscle attachments of fonΔ17 larvae observed upon addition of L-DOPA (black arrowheads). (G–I) Distribution of hemocytes at MASs in filleted larvae. Low magnification images can be found in Fig. S3. (G) Hemocytes (detected through labeling for Hemese) are found at low levels near intact MASs. (H,I) In wild-type muscles that have been mechanically damaged during dissection (H) or upon fon-mediated muscle detachment (I), hemocytes are recruited to sites of muscle attachment and/or damaged muscles. Arrowheads denote the MAS in panels G–I. Scale bars: 1 mm in A,D; 500 µm in B,E; 100 µm in C,F–I.